Hong Kong Med J 2022 Apr;28(2):124–32 | Epub 14 Apr 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of pregnant

women towards COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey

WY Lok, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; CY Chow, MB, ChB; CW Kong, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; William WK To, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr WY Lok (happyah2@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: This study investigated the knowledge,

attitudes, and behaviours of pregnant women

towards coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19),

as well as obstetric services provided by public

hospitals (eg, universal screening) during the

pandemic.

Methods: This cross-sectional survey was

performed in the antenatal clinics of Kowloon East

Cluster, Hospital Authority. Questionnaires were

distributed to pregnant women for self-completion

during follow-up examinations.

Results: In total, 623 completed questionnaires

were collected from 28 July 2020 to 13 August 2020.

Within this cohort, 83.1% of the women expressed

high levels of worry (41.9% very worried and 41.3%

worried) about contracting COVID-19 during

pregnancy, 70.5% believed that maternal COVID-19

could cause intrauterine infection of their fetuses,

and 84.3% objected to banning husbands from

accompanying wives during labour and delivery.

Most women (80.6%) agreed with universal screening

for COVID-19 at certain points during pregnancy.

Logistic regression modelling showed that women

who were very worried about contracting COVID-19 (P=0.005) and women in their third trimester of

pregnancy (P=0.009) were more likely to agree with

universal screening during pregnancy; women with

higher income (P=0.017) and women who planned

to deliver in a private hospital (P=0.024) were more

likely to disagree with such screening.

Conclusion: Pregnant women expressed high levels

of worry about contracting COVID-19 during

pregnancy; universal screening during pregnancy

was acceptable to a large proportion of our

participants. Efforts should be made to specifically

include pregnant women when launching any

population screening programme for COVID-19.

New knowledge added by this study

- This study investigated the knowledge, psychosocial behavioural responses, and opinions of pregnant women in Hong Kong towards coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

- A large majority of the women in this study expressed worry about COVID-19, despite a lack of comprehensive knowledge about the disease.

- More than 80% of the women agreed with universal screening for COVID-19 in pregnant women during visits to clinics and hospitals.

- Universal screening should be incorporated as part of routine clinical management and in-patient care for pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Husbands should be allowed to accompany their wives during labour and delivery if a rapid screening method shows that the husbands do not have COVID-19.

- Online resources should be developed to enhance public knowledge about COVID-19-related complications in pregnancy.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

(SARS-CoV-2), has been a worldwide pandemic

for more than 2 years. The first reported case of

COVID-19 occurred in Wuhan, China in late

December 2019.1 2 On 21 January 2020, the first confirmed imported case of COVID-19 in Hong

Kong was identified in a mainland Chinese tourist

who arrived from Wuhan by high-speed rail.3

The dynamics of the current COVID-19

pandemic closely resemble the previous SARS

epidemic because each has involved a respiratory

disease caused by a coronavirus. Despite various measures and strategies employed by the Hong Kong

government and the public in an effort to combat

viral spread, a third wave of infections occurred in

the middle of 2020, leading to >100 new confirmed

COVID-19 cases daily for 12 days consecutively

in late July 2020.4 In response, the government

announced a variety of new measures to contain the

spread of COVID-19.

Pregnant women in Hong Kong are particularly

worried about the effects of COVID-19 because of

their vulnerable immune status during pregnancy,

as well as the fear of vertical transmission to the

neonate.5 6 During the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong

Kong, 12 pregnant women contracted SARS and three

died. Among the survivors, SARS was associated with

poor outcomes including high rates of mechanical

ventilation and intensive care unit admission, as well

as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, and

intrauterine growth restriction. However, there was

no evidence of perinatal transmission of SARS to

infants.7 In early 2020, the first reports of COVID-19

in Chinese pregnant women were published.8 9

Systematic reviews concerning maternal and

perinatal outcomes in cases of COVID-19 have since

been published.10 11 12 13

To our knowledge, no studies have specifically

assessed the basic knowledge and concerns of

pregnant women with respect to COVID-19,

or their acceptance of universal screening for

infection by the causative virus (SARS-CoV-2);

such information is important for the establishment

of public education campaigns and launching

COVID-19 population screening efforts that target pregnant women. This study aimed to evaluate the

opinions of pregnant women concerning obstetric

services provided during the pandemic, with

particular focus on acceptance of universal screening

for COVID-19 during pregnancy. The study also

explored the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of

pregnant women towards the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey was conducted in two

antenatal clinics in the Kowloon East Cluster of

Hong Kong. The questionnaires were distributed

to consecutive pregnant women who attended

antenatal follow-up examinations in the two clinics

from July 2020 to August 2020.

The paper questionnaires were anonymous,

self-administered, and available in either Chinese

or English. The first section of the questionnaire

collected basic demographic data from the recruited

women. The remaining sections comprised four

domains with 31 total questions; five questions had

multiple parts. The four domains included questions

regarding (1) knowledge of COVID-19 in pregnancy,

(2) attitudes towards COVID-19, (3) social

behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic, and (4)

opinions about the provision of obstetric services

during the COVID-19 pandemic. The questions were

answered in the following formats (as appropriate):

binary (Yes/No), three options (Yes/No/unsure),

4-point Likert scale, or selection of available answers

(online supplementary Appendix).

The study protocol was approved by the

Research Ethics Committee of Kowloon East Cluster,

Hospital Authority. SPSS software (Windows version

20.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States)

was used for data entry and analysis. Descriptive

categorical data were expressed as numbers and

percentages; they were compared and analysed by the

Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used

to identify clinical covariates that were significantly

associated with pregnant women’s opinions about

universal screening for COVID-19. A P value of

<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants

The questionnaires were distributed to 700

pregnant women for 17 days, from 28 July 2020

to 13 August 2020. Seven women were excluded

because they could not understand either version

of the questionnaire (ie, Chinese or English), while

54 women refused to participate in the study. Of

the 639 women who completed the questionnaire,

16 were excluded because of missing answers; thus,

623 participants were included in the final analysis.

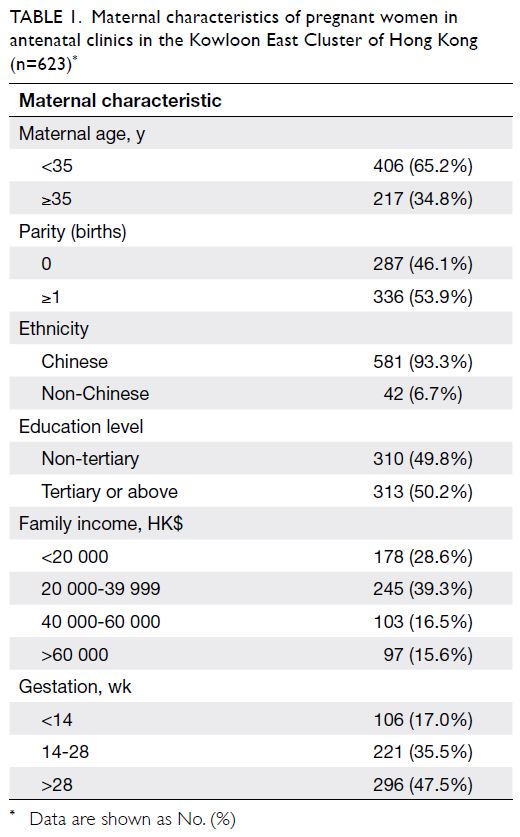

Nearly all participants were Chinese (93.3%). Half of the participants (50.2%) had an education level of

tertiary or above; 47.5% were in the third trimester of

pregnancy (Table 1).

Table 1. Maternal characteristics of pregnant women in antenatal clinics in the Kowloon East Cluster of Hong Kong (n=623)

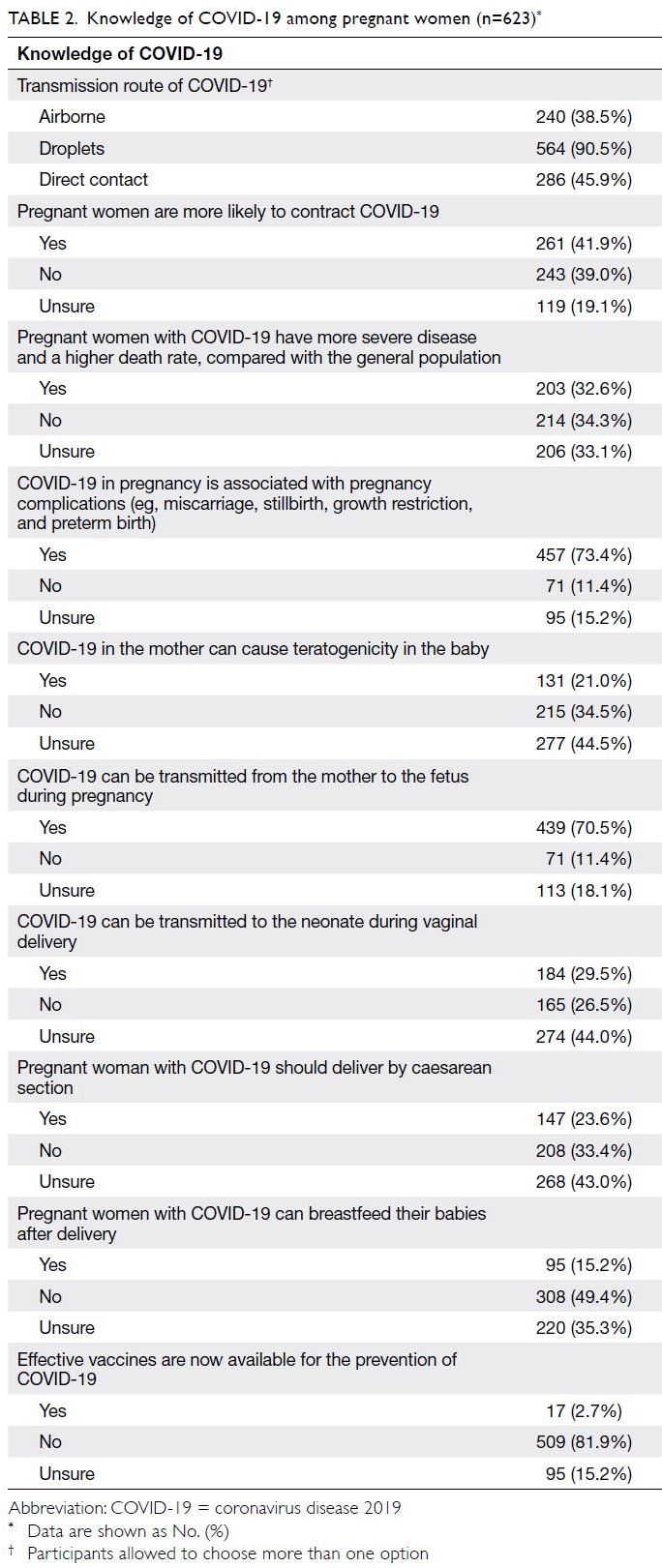

Knowledge of COVID-19 in pregnancy

A large proportion of the participants (90.5%)

knew that COVID-19 was transmitted by droplets,

while more than one-third of participants (38.5%)

thought that airborne transmission of COVID-19

was also possible. Additionally, more than one-third

of participants (41.9%) thought that they were

more likely to contract COVID-19, while 32.6%

presumed that pregnant women with COVID-19

would have more severe disease and experience

higher mortality rates compared with the general

population. Moreover, 73.4% of participants

thought that maternal COVID-19 was associated

with pregnancy complications such as miscarriage,

stillbirth, growth restriction, and preterm birth;

70.5% believed that maternal COVID-19 could be

vertically transmitted to the fetus during pregnancy.

Substantial proportions of participants were unsure

whether COVID-19 in pregnant women could lead

to teratogenicity in the fetus (44.5%), or whether

women with COVID-19 should be able to perform

vaginal delivery (44%) or breastfeed (35.3%) [Table 2].

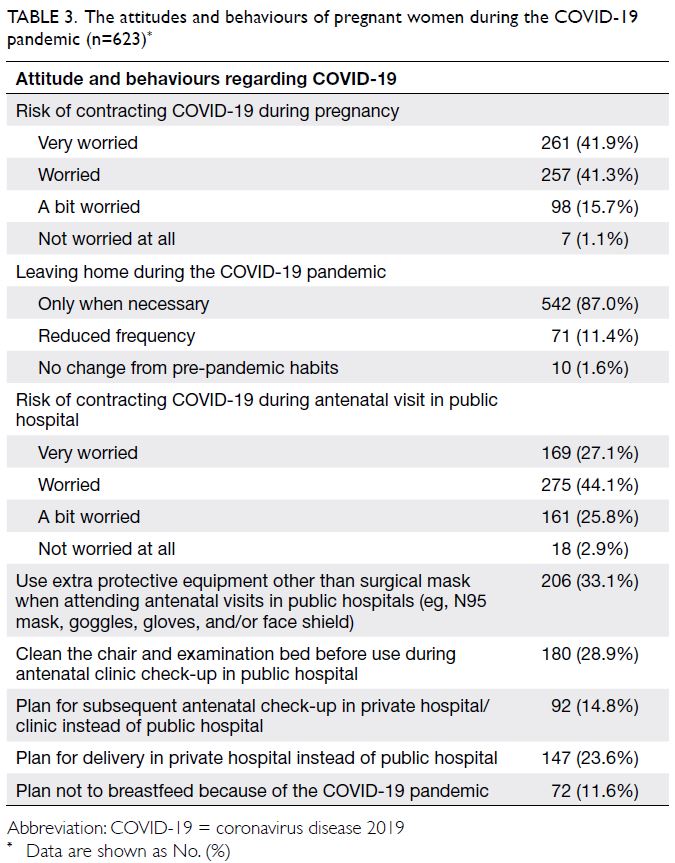

Attitudes and behaviours of pregnant women

during the COVID-19 pandemic

The majority (83.1%) of participants were worried

about contracting COVID-19 during pregnancy

(41.9% were very worried and 41.3% were worried).

Similarly, 87.0% of participants only left home

when necessary during the pandemic, while 71.3%

of participants were worried about contracting

COVID-19 during their antenatal visits in public

hospitals (27.1% were very worried and 44.1% were

worried). One-third of the participants (33.1%) used

extra protective gear other than surgical masks when

attending antenatal clinics (eg, N95 masks, goggles,

gloves, or face shields), while 28.9% of participants

reported cleaning the chair and examination bed

with disinfectants before use during an antenatal

clinic visit. Almost one-quarter of participants

(23.6%) intended to deliver in a private hospital,

among which 49.7% (73/147) believed that the risk of

contracting COVID-19 was lower when delivering in

a private hospital than in a public hospital. Moreover,

61.2% of participants who intended to deliver in a

private hospital (90/147) stated that public hospitals no longer permitted husbands to accompany wives

during labour and delivery during the COVID-19

pandemic, while private hospitals continued to allow

such practices. Seventy-two participants (11.6%)

decided not to breastfeed because of the COVID-19

pandemic, of which 77.8% (56/72) believed that

COVID-19 could be transmitted to the baby through

breast milk even if the mother had asymptomatic

illness (Table 3).

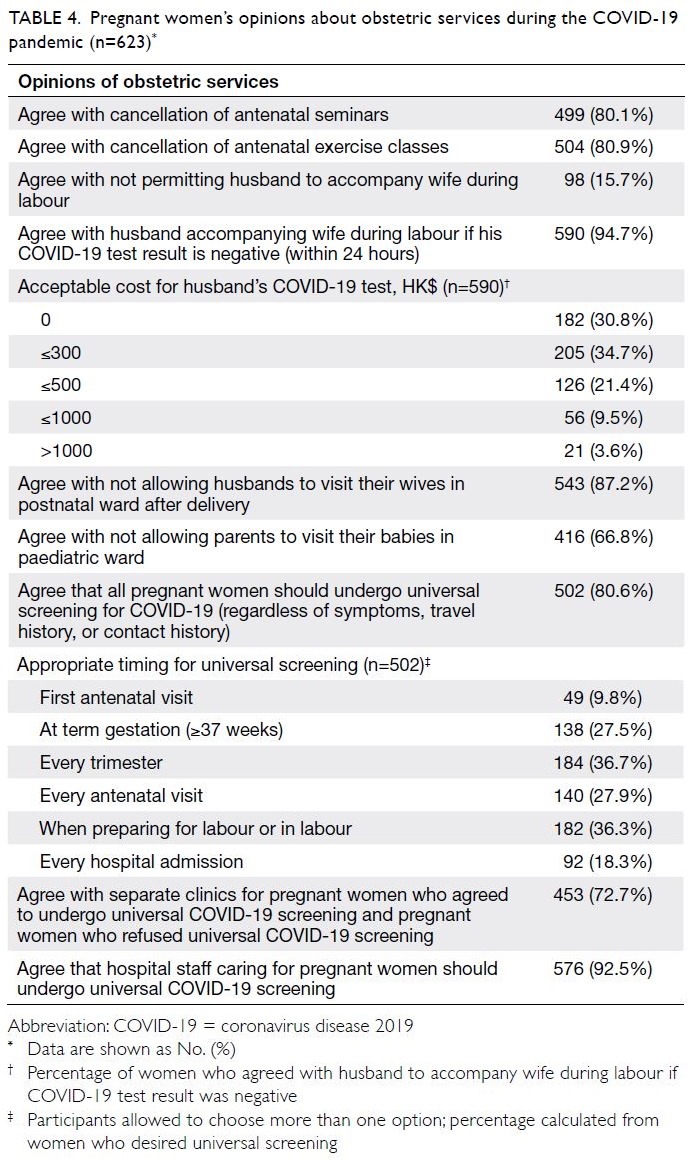

Opinions about the provision of obstetric

services during the COVID-19 pandemic

Most participants agreed that antenatal seminars

and antenatal exercise classes should be cancelled,

and that visitors should not be allowed in postnatal

wards and neonatal wards (including husbands and

parents). However, a large proportion of participants

(84.3%) objected to banning husbands from

accompanying wives during labour and delivery

in the COVID-19 pandemic; 94.7% of participants

agreed that husbands a with negative COVID-19

test results should be allowed to accompany wives

during labour, and 65.6% agreed with paying for

such a test if the price was ≤HK$300. While 80.6%

of participants agreed that pregnant women should

undergo universal screening for COVID-19 during

pregnancy, their preferences varied regarding the

optimal time to perform such screening. The most

popular option was screening in every trimester

(36.7%), followed by screening when preparing for

labour or in labour (36.3%). Almost all participants

(92.5%) agreed that hospital staff caring for pregnant

women should undergo regular universal COVID-19

screening (Table 4).

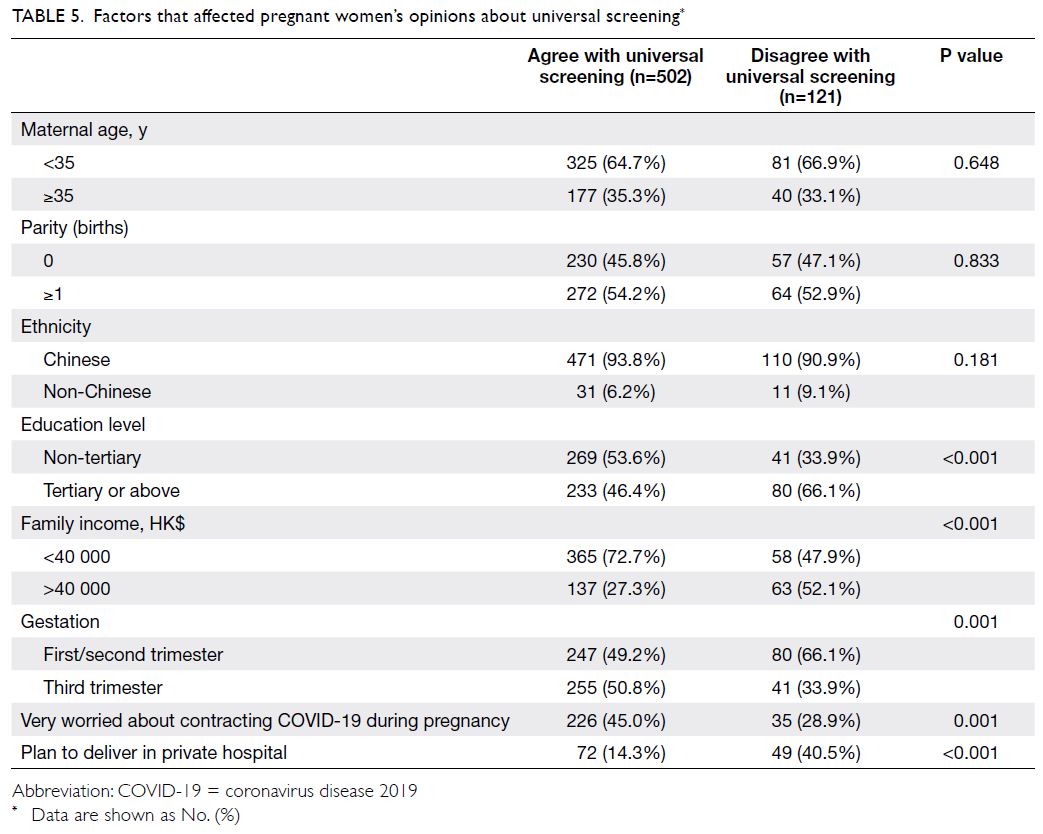

Factors that affect pregnant women’s

opinions about universal screening for COVID-19

Univariate analysis showed that a significantly

greater proportion of women who agreed with

universal screening had family income <$40 000

(72.7% vs 47.9%, P<0.001), were very worried about

contracting COVID-19 during pregnancy (45.0%

vs 28.9%, P=0.001), or were in their third trimester

(50.8% vs 33.9%, P=0.001). Conversely, women who

did not agree with screening were more likely to

have an education level of tertiary or above (46.4% vs

66.1%, P<0.001) and intended to deliver in a private

hospital (14.3% vs 40.5%, P<0.001). However, no

differences were observed in terms of parity, ethnicity,

or the proportion of women with advanced maternal

age between women who did and did not agree with

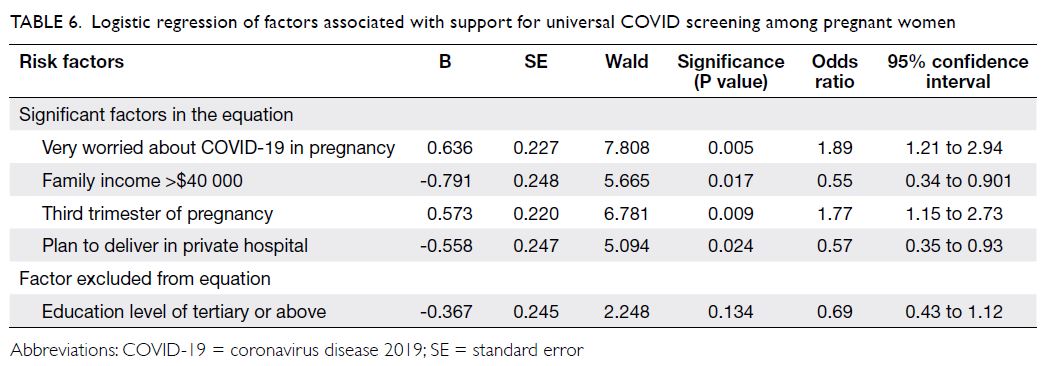

universal screening (Table 5). Logistic regression

analysis showed that women who were very worried

about contracting COVID-19 (P=0.005, odds ratio

[OR]=1.89) and women in their third trimester of

pregnancy (P=0.009, OR=1.77) were more likely to agree with universal screening during pregnancy;

women with family income >$40 000 (P=0.017,

OR=0.55) and women who planned to deliver in a

private hospital (P=0.024, OR=0.57) were more likely

to disagree with such screening. Education level was

not a significant risk factor according to multivariate

analysis (Table 6).

Table 6. Logistic regression of factors associated with support for universal COVID screening among pregnant women

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first large study

in Hong Kong concerning the knowledge and

psychobehavioural responses of pregnant women

towards the COVID-19 pandemic. While basic

concepts concerning COVID-19 appeared to be

understood by our study participants (eg, COVID-19

is primarily spread through droplets and that

vaccines were not available at the time of the study),

there was the potential for improved knowledge

regarding other concepts. For instance, there is

evidence that, compared with the general population,

pregnant women are not more susceptible to

contract COVID-19 and the majority of them do

not experience severe complications of COVID-19

in pregnancy; however, it has been suggested that

pregnant women may be at higher risk of more

severe disease than the non-pregnant women in

terms of intensive care unit admission particularly

when they are in the third trimester.14 In a systematic

review, the rate of severe pneumonia in pregnant

women with COVID-19 ranged from 0% to 14%;

sporadic maternal death was reported in case reports

of patients with severe COVID-19.10 Furthermore, approximately 70% of women in our cohort thought

that maternal COVID-19 led to increased pregnancy

complications and carried a high rate of vertical

transmission, more evidence in these areas are

now emerging. Systematic reviews have shown

that there could be increased risks of miscarriage

and stillbirths in pregnant women with COVID-19;

and pregnant women with symptomatic infection

had two-to-three-fold increased risks of preterm

birth, most of these were iatrogenic.12 13 In contrast,

there is no evidence showing increased risk for

teratogenicity or intrauterine growth restriction of

baby with maternal COVID-19 infection.15 The risks

of vertical transmission of COVID-19, which despite

remaining controversial, has now been supported

by systematic reviews.16 Online resources, such as

websites or mobile apps, should be considered to

provide updated information regarding the effects of

COVID-19 on pregnancy.

Our pregnant women demonstrated

uncertainties concerning the mode of delivery and

breastfeeding should they contract COVID-19,

mainly because they feared disease transmission

during delivery or via breast milk. While the

literature has reported that vertical transmission

during vaginal delivery or in the peripartum period could be possible, the actual risks appeared to be

very low and caesarean may not prevent vertical

transmission.17 Indeed, vaginal delivery is not contra-indicated

although high rates of caesarean delivery

have been reported in studies, with up to 85.9% of

deliveries via caesarean section in a large series of

116 women with COVID-19 (38.8% had COVID-19

pneumonia).18 However, there has been conflicting

evidence regarding the safety of breastfeeding.19

According to the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention guidelines, breastfeeding is not contra-indicated

when a mother contracts COVID-19 but

should be determined by the mother’s overall health status.20 Available data suggest that SARS-CoV-2 is

not detectable in breast milk samples from mothers

with COVID-19. While some authors have suggested

isolation of the mother and baby,21 a large series of 82

neonates roomed with mothers who had COVID-19

in a closed Giraffe isolette (with necessary contact

precautions during direct breastfeeding) showed

that these neonates remained free of COVID-19.22

A large majority of the pregnant women in

our cohort expressed worry about contracting

COVID-19 during pregnancy or antenatal follow-up

examinations in public hospitals. A survey of the

psychological and behavioural responses of pregnant

women during the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong

revealed that pregnant women had slightly greater

anxiety during SARS than before the epidemic.23 In addition to their memories of the SARS epidemic,

the widespread worry among pregnant women

in our cohort could be explained by the timing of

our survey, which was conducted during a wave of

COVID-19 transmission in Hong Kong. We might

have been able to partially alleviate their fears if we

had stated that the World Health Organization’s

provisional case fatality rate of COVID-19 was 3.7%

during the study period, considerably lower than the

10% of SARS.24 A substantial proportion of pregnant

women (approximately 20%) in our survey revealed

that they had considered subsequent follow-up

examinations and delivery in private hospitals, which

they believed to be safer; however, this proportion

might be an underestimation because women who

intended to deliver in a private hospital might not

have attended our clinics for any examinations.

More than 80% of women objected to banning

husbands from accompanying wives during

labour and delivery in the COVID-19 pandemic,

particularly if those husbands had negative

COVID-19 test results. Indeed, many women

reported considering delivery in a private hospital for

this reason. A previous study conducted in our unit

demonstrated that partner companionship during

labour could offer emotional support and enhance

maternal satisfaction during delivery.25 As extended

screening becomes available, husbands should be

offered the opportunity to undergo screening when

their wives are admitted for labour and delivery to

address this need for partner companionship.

Because COVID-19 is highly transmissible

and COVID-19 carriers may be asymptomatic,

universal screening of all patients is important to

curb disease spread in the community. In August

2020, the Hong Kong Government announced that

a voluntary universal COVID-19 testing programme

would be launched. In partnership with the Board

of Directors of Yan Chai Hospital, the government’s

trial community testing programme for COVID-19

among pregnant women was launched on 10 August

2020, although we did not have data regarding this

programme during our study. Around 1 month

after our study, the Hospital Authority extended the

COVID-19 screening to all asymptomatic in-patients

including pregnant women. Our survey showed that

approximately 80% of pregnant women agreed with

universal screening for COVID-19 in the hospital

setting. While their opinions differed concerning

the frequency and timing of screening, women in

the third trimester of pregnancy generally wanted to

confirm that they were COVID-19-free at the time of

delivery. However, it is understandable that women

with higher family income and women who intended

to deliver in a private hospital might not agree with

universal screening in public hospitals. In the

literature, universal screening for COVID-19 in

pregnant women has mainly focused on screening at the time of admission for delivery; this practice was

implemented as early as March 2020 in countries

where community prevalence rates were considered

high. Such universal screening has yielded prevalence

rates of 0.43% to 13.7% for asymptomatic COVID-19

in pregnant women, depending on the local

epidemiological situation.26 27 28 29 In the latest update, the

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

recommended all pregnant women admitted to

hospitals in England should be offered SARS-CoV-2

testing regardless of symptoms.30 Ideally, such

screening enables early identification and cohorting

of asymptomatic women with COVID-19, thus

protecting other pregnant women, their newborn

infants, and healthcare staff. Negative test results

can be used to reassure the women and encourage

them to practise breastfeeding. The inclusion of

universal screening for COVID-19 among pregnant

women should be a key aspect of maternity care

after considering the need for laboratory support,

availability of isolation facilities and personal

protective equipment, and (most importantly)

the cost-effectiveness of screening based on the

estimated community prevalence of COVID-19.

There were some limitations in this study.

While we performed a small pilot study (involving

face-to-face interviews) when designing and refining

the survey questions to confirm responses by

pregnant women, we did not conduct further formal

validation or assessment of internal reliability.

The questionnaires were developed around the

peak of the third wave in Hong Kong; the results

drawn from the survey reflected only the recruited

women’s knowledge and opinions at that time

point. Thus, our findings might not be generalisable

to other populations or other points in the

COVID-19 pandemic with different epidemiological

characteristics.

Conclusion

Among pregnant women, knowledge about COVID-19 during pregnancy should be strengthened

through public education that specifically focuses on

COVID-19-related complications in pregnancy. A

large majority of pregnant women expressed worry

about contracting COVID-19 during pregnancy,

and most women in the study agreed with universal

screening during pregnancy. While the optimal

timing for screening in pregnancy requires further

consideration, there is a need to specifically

include pregnant women in population screening

programmes for COVID-19.

Author contributions

Concept or design: WY Lok, CW Kong, WWK To.

Acquisition of data: WY Lok, CY Chow.

Analysis or interpretation of data: WY Lok, CW Kong, WWK To.

Drafting of the manuscript: WY Lok, CW Kong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors

Acquisition of data: WY Lok, CY Chow.

Analysis or interpretation of data: WY Lok, CW Kong, WWK To.

Drafting of the manuscript: WY Lok, CW Kong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Kowloon Central/Kowloon East Research Ethics Committees (Ref: KC/KE-20-

0226/ER-3).

References

1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med

2020;382:727-33. Crossref

2. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients

infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China.

Lancet 2020;395:497-506. Crossref

3. Cheung E. China Coronavirus: death toll almost doubles

in one day as Hong Kong reports its first two cases. South

China Moring Post. 2020 Jan 22. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/3047193/china-coronavirus-first-case-confirmed-hong-

kong. Accessed 16 Aug 2020.

4. Ting V, Leung K, Cheung E. Hong Kong third wave: city’s

Covid-19 social-distancing measures set to be extended

after recent spike in cases. South China Moring Post.

2020 Aug 1. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/news/hongkong/healthenvironment/article/3095642/hong-kong-third-wave-more-100-new-covid-19-cases. Accessed 16 Aug 2020.

5. Dashraath P, Wong JL, Lim MX, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2020;222:521-31. Crossref

6. Rasmussen SA, Smulian JC, Lednicky JA, Wen TS, Jamieson DJ. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and

pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2020;222:415-26. Crossref

7. Wong SF, Chow KM, Leung TN, et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with severe acute respiratory

syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:292-7. Crossref

8. Schwartz DA. An analysis of 38 pregnant women with

COVID-19, their newborn infants, and maternal-fetal

transmission of SARS-CoV-2: maternal coronavirus

infections and pregnancy outcomes. Arch Pathol Lab Med

2020;144:799-805. Crossref

9. Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, et al. Clinical characteristics and

intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19

infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review

of medical records. Lancet 2020;395:809-15. Crossref

10. Juan J, Gil MM, Rong Z, Zhang Y, Yang H, Poon LC. Effect

of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on maternal, perinatal and neonatal outcome: systematic review.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020;56:15-27. Crossref

11. Zaigham M, Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal

outcomes with COVID-19: a systematic review of 108

pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020;99:823-9. Crossref

12. Kazemi SN, Hajikhani B, Didar H, et al. COVID-19 and

cause of pregnancy loss during the pandemic: a systematic

review. PLoS One 2021;16:e0255994. Crossref

13. Wei SQ, Bilodeau-Bertrand M, Liu S, Auger N. The impact

of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review

and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2021;193:E540-8. Crossref

14. Vousden N, Bunch K, Morris E, et al. The incidence,

characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women

hospitalized with symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-

2 infection in the UK from March to September 2020:

a national cohort study using the UK Obstetric Surveillance

System (UKOSS). PLoS One 2021;16:e0251123. Crossref

15. Mullins E, Hudak ML, Banerjee J, et al. Pregnancy and

neonatal outcomes of COVID-19: coreporting of common

outcomes from PAN-COVID and AAP-SONPM registries.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2021;57:573-81. Crossref

16. Musa SS, Bello UM, Zhao S, Abdullahi ZU, Lawan MA,

He D. Vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic

review of systematic reviews. Viruses 2021;13:1877. Crossref

17. Sinaci S, Ocal DF, Seven B, et al. Vertical transmission of

SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cross-sectional study from a

tertiary center. J Med Virol 2021;93:5864-72. Crossref

18. Yan J, Guo J, Fan C, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in

pregnant women: a report based on 116 cases. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2020;223:111.e1-14. Crossref

19. Poon LC, Yang H, Kapur A, et al. Global interim guidance

on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) during

pregnancy and puerperium from FIGO and allied partners:

information for healthcare professionals. Int J Gynecol

Obstet 2020;149:273-86. Crossref

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Care for

breastfeeding people. Interim guidance on breastfeeding

and breast milk feeds in the context of COVID-19.

Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/care-for-breastfeeding-women.html. Accessed 11 Aug 2020.

21. Griffin I, Benarba F, Peters C, et al. The impact of

COVID-19 infection on labor and delivery, newborn

nursery, and neonatal intensive care unit: prospective

observational data from a single hospital system. Am J

Perinatol 2020;37:1022-30. Crossref

22. Salvatore CM, Han JY, Acker KP et al. Neonatal

management and outcomes during the COVID-19

pandemic: an observation cohort study. Lancet Child

Adolesc Health 2020;4:721-7. Crossref

23. Lee DT, Sahotab D, Leung TN, Yip AS, Lee FF, Chung TK.

Psychological responses of pregnant women to an

infectious outbreak: a case-control study of the 2003 SARS

outbreak in Hong Kong. J Psychosom Res 2006;61:707-13. Crossref

24. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease

(COVID-2019) situation reports-204. Available from:

https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200811-covid-19-sitrep-204.pdf?sfvrsn=1f4383dd_2. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

25. Chung VW, Chiu JW, Chan DL, To WW. Companionship

during labour promotes vaginal delivery and enhances

maternal satisfaction. Hong Kong J Gynaecol Obstet

Midwifery 2017;17:12-7.

26. Sutton D, Fuchs K, D’Alton M, Goffman D. Universal

screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery.

N Engl J Med 2020;382:2163-4. Crossref

27. Fassett MJ, Lurvey LD, Yasumura L, et al. Universal

SARS-Cov-2 screening in women admitted for delivery

in a large managed care organization. Am J Perinatol

2020;37:1110-4. Crossref

28. Tanacana A, Erola SA, Turgay B, et al. The rate of

SARS-CoV-2 positivity in asymptomatic pregnant women

admitted to hospital for delivery: experience of a pandemic

center in Turkey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol

2020;253:31-4. Crossref

29. Herraiz I, Folgueira D, Villalaín C, Forcén L, Delgado R, Galindo A. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 before

labor admission during Covid-19 pandemic in Madrid. J

Perinat Med 2020;48:981-4. Crossref

30. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Principles for the testing and triage of women seeking

maternity care in hospital settings, during the COVID-19

pandemic. A supplementary framework for maternity

healthcare professionals. version 2. Available from:

https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/2020-08-10-principles-for-the-testing-and-triage-of-women-seeking-maternity-care-in-hospital-settings-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.pdf. Accessed 2

Oct 2020.