Changes in cardiovascular disease risk predicted by the Framingham risk model in the Hong Kong population between 2003-2005 and 2014-2015: data from Population Health Surveys

Hong Kong Med J 2024 Jun;30(3):202–8 | Epub 29 May 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Changes in cardiovascular disease risk predicted by the Framingham risk model in the Hong Kong population between 2003-2005 and 2014-2015: data from Population Health Surveys

Brian YC Sung, MB, BS1; Eric HM Tang, BSc2; Laura Bedford, BSc2; Carlos KH Wong, MPhil, PhD2,3; Emily TY Tse, MB, BS, FHKAM (Family Medicine)2; Esther YT Yu, MB, BS, FHKAM (Family Medicine)2; Bernard MY Cheung, MB, BChir, PhD1; Cindy LK Lam, MB, BS, MD2

1 Department of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Bernard MY Cheung (mycheung@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The Framingham risk model estimates

a person’s 10-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.

This study used this model to calculate the changes

in sex- and age-specific CVD risks in the Hong

Kong Population Health Survey (PHS) 2014/15

compared with two previous surveys conducted

during 2003 and 2005, namely, PHS 2003/2004 and

Heart Health Survey (HHS) 2004/2005.

Methods: This study included individuals aged 30 to

74 years from PHS 2014/15 (n=1662; n=4 445 868

after population weighting) and PHS 2003/2004 and

HHS 2004/2005 (n=818; n=3 495 074 after population

weighting) with complete data for calculating the

risk of CVD predicted by the Framingham model.

Sex-specific CVD risks were calculated based on

age, total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein

cholesterol levels, mean systolic blood pressure,

smoking habit, diabetic status, and hypertension

treatment. Mean sex- and age-specific CVD risks

were calculated; differences in CVD risk between the

two surveys were compared by independent t tests.

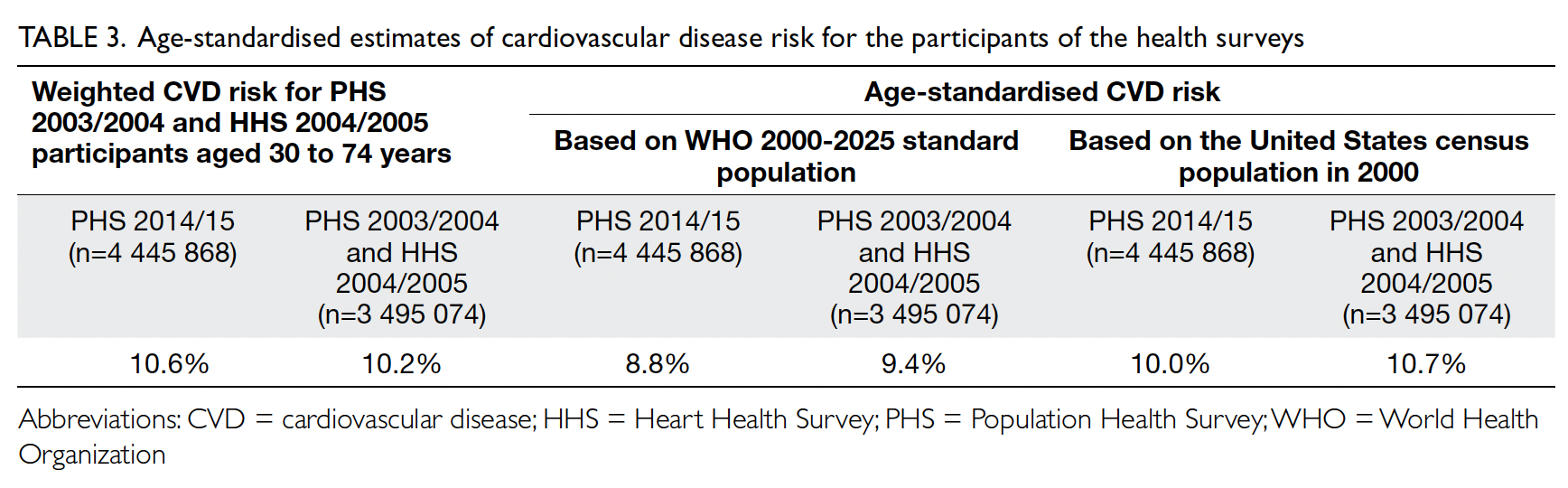

Results: The difference in 10-year CVD risk from

2003-2005 to 2014-2015 was not statistically

significant (10.2% vs 10.6%; P=0.29). After age

standardisation according to World Health

Organization world standard population data, a small

decrease in CVD risk was observed, from 9.4% in

2003-2005 to 8.8% in 2014-2015. Analysis according

to age-group showed that more participants aged 65 to 74 years were considered high risk in 2003

to 2005 (2003-2005: 66.8% vs 2014-2015: 53.1%;

P=0.028). This difference may be due to the decrease

in smokers among men (2003-2005: 30.5% vs 2014-2015: 24.0%; P<0.001).

Conclusion: From 2003-2005 to 2014-2015, there

was a small decrease in age-standardised 10-year

CVD risk. A holistic public health approach

simultaneously targeting multiple risk factors is

needed to achieve greater decreases in CVD risk.

New knowledge added by this study

- The stagnation in 10-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk between 2003 and 2015 suggests that despite improvements in treatment, more effective prevention strategies (eg, improvements in diet and physical activity levels) are needed.

- The effect of the decreasing number of current smokers was not strongly reflected in the change in 10-year CVD risk. This may be due to an increased prevalence of diabetes and an increased proportion of participants receiving antihypertensive medications.

- The findings suggest that the use of lipid-lowering drugs and antihypertensive medications does not effectively translate into overall cardiovascular risk reduction in the Hong Kong population, unless these treatments are simultaneously paired with prevention strategies targeting CVD risk factors.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) constitutes a

spectrum of diseases that affect the heart and blood

vessels. Worldwide, CVD is the leading cause of

death as well as a major cause of premature death

and chronic disability in numerous regions.1 In 2017,

CVD was responsible for an estimated 17.8 million

deaths, representing 31% of all global deaths.2

Hypertension, smoking status, hyperlipidaemia,

and diabetes mellitus are prominent risk factors for

CVD.3 The global prevalence of CVD risk factors is

increasing. Currently, an estimated 15% of the world’s

population (1.13 billion people) has hypertension,

and the prevalence is expected to increase to 29%

by 2025.4 5 Additionally, the global prevalence of

diabetes increased from 211 million in 1990 to 476

million in 2017, representing a 129.7% increase in

nearly three decades.6 The prevalences of CVD and

its risk factors are expected to continue to increase

in the near future due to industrialisation and

population ageing. Fortunately, the World Health

Organization (WHO) has estimated that premature CVD is preventable in >75% of cases, and risk factor

amelioration can help reduce the burden caused by CVD.7

The risk of CVD over the next 10 years for an

individual can be estimated using prediction models.

Cardiovascular disease risk prediction is important

at the individual and population levels. At the

individual level, CVD risk prediction allows primary

care medical professionals to identify high-risk

patients. Risk factors for CVD, such as hypertension,

can be treated accordingly to reduce the patient’s

future risk of CVD. At the population level, CVD

risk trends allow health policy planners to make

evidence-based decisions and review current public

health strategies used in CVD prevention.8

Changes in CVD risk can serve as a reference

to indicate changes in public health status within

a population. Two studies have evaluated changes

in the 10-year CVD risk in the United States (US)

population. In a study by Ajani and Ford,9 risk models

adopted by the National Cholesterol Education

Program Adult Treatment Panel III were utilised to

estimate coronary heart disease risk, rather than the

more precise Framingham formulae for estimation

of overall CVD risk. Notably, their analysis lacked

age stratification. On the other hand, Lopez-Jimenez

et al10 evaluated the changes in CVD risk between

1976 and 2004. To our knowledge, no previous study

has evaluated the change in 10-year CVD risk in an

Asian population, and insights are needed regarding

the cardiovascular health status of the population in

a more recent time period.

In this study, we aimed to calculate and

compare the changes in sex- and age-specific CVD

risks predicted by the Framingham model in a

Hong Kong general population by using the Hong

Kong Population Health Survey (PHS) 2014/15 in

combination with two previous surveys conducted

in 2003 to 2005, namely, PHS 2003/2004 and Heart

Health Survey (HHS) 2004/2005.

Methods

Study design and sampling

The data in this study were sourced from PHS

2003/200411 and PHS 2014/15.12 Population

Health Surveys are territory-wide cross-sectional

surveys conducted by the Department of Health of

the Hong Kong SAR Government. These surveys

target the land-based non-institutional population of

individuals aged ≥15 years in Hong Kong, excluding

foreign domestic helpers and visitors. Systematic

replicate sampling was adopted to select living

quarters that were representative of the Hong Kong

general population. All domestic households in the

selected living quarters and household members in

the target population were individually surveyed.

Written consent was obtained from individuals who agreed to participate in a PHS. Participants

were invited to complete a face-to-face interview,

where they provided information about their socio-demographic

characteristics, disease status, and

daily lifestyle habits. After the interview, consenting

participants aged 15 to 84 years were randomly

selected to undergo a health examination that

included physical measurements and biochemical

testing.12 Health examinations for participants of

PHS 2003/2004 were conducted as part of the HHS 2004/2005.

The STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of

Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist

was followed for preparing this manuscript.

Predicted risk of cardiovascular disease over

the next 10 years

The main outcome of this study was the predicted risk

of CVD over the next 10 years among people aged 30

to 74 years. Thus far, no specific prediction models

have been developed for the Hong Kong population.

In this study, we adopted the prediction model for

primary care developed by the Framingham Heart

Study Cohort in the general adult population aged

30 to 74 years.13 The Framingham CVD risk model

was validated and can be applied to the Chinese

population, but requires recalibration in men.14 A

CVD event was defined as a composite of coronary

heart disease, cerebrovascular events, peripheral

artery disease, and heart failure in the Framingham

model. The predicted CVD risk over the next 10

years was calculated for each participant using the

following information: age, total cholesterol level,

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, systolic

blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication, current smoking status, and diabetes status.

Statistical analysis

A complete-case analysis approach was utilised

in this study. Descriptive statistics were used to

present the characteristics of included individuals.

Sex- and age-specific predicted CVD risks in 2003-2005 and 2014-2015 were calculated to summarise

the change in risk according to sex and age-group.

Significant differences in the above factors between

the two PHSs were tested by independent t test or

Chi squared test, as appropriate.

To summarise results at the population level,

population weighting established by the Department

of Health was applied according to age-group and

sex for participants in each PHS. To compare results

at the population level, age-standardised predicted

CVD risk was calculated using WHO 2000-2025

world standard population data15 and the US population census data in 2000.16

All statistical analyses were performed with

SPSS software (Windows version 26.0; IBM Corp,

Armonk [NY], US). All significance tests were

two-tailed, and P values <0.05 were considered

statistically significant.

Results

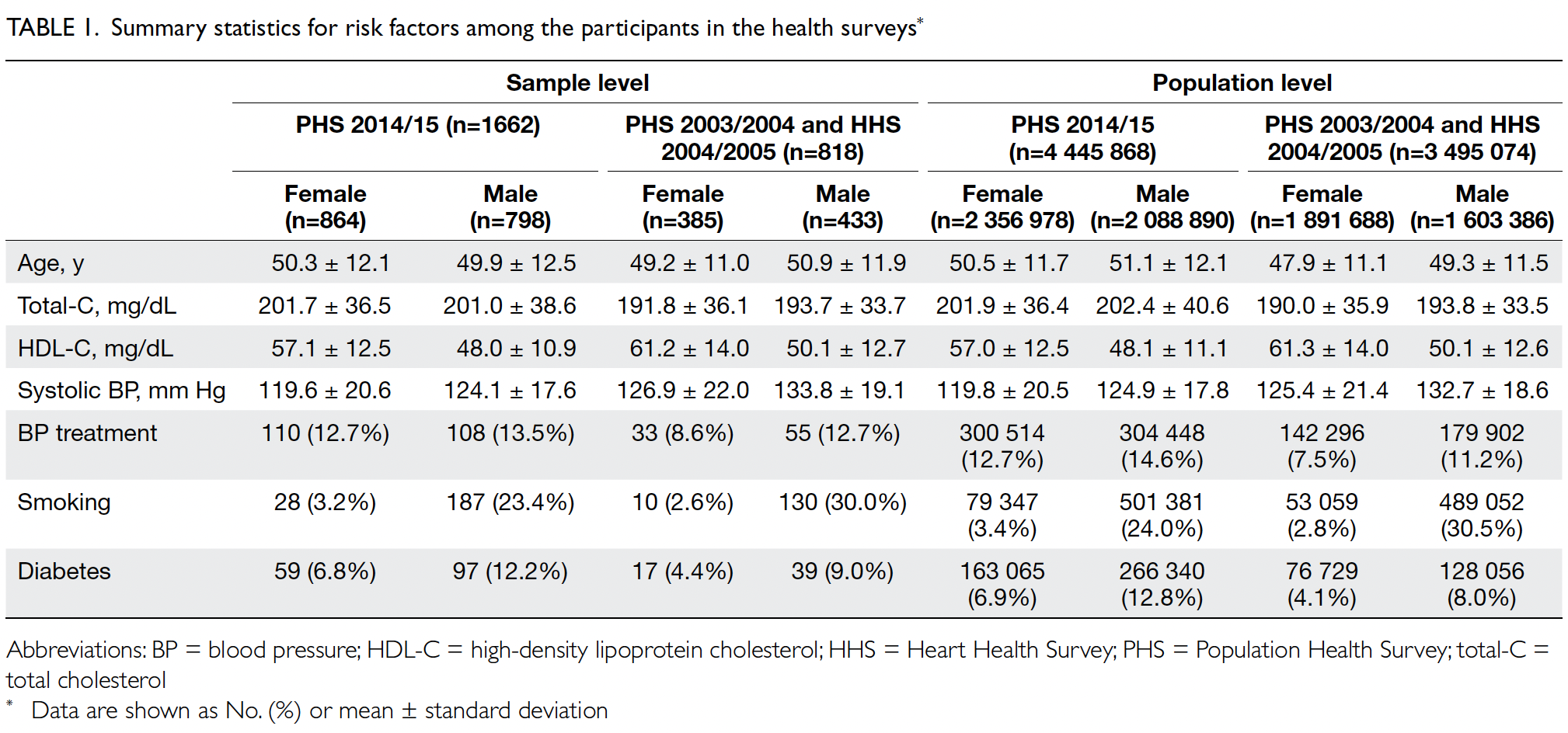

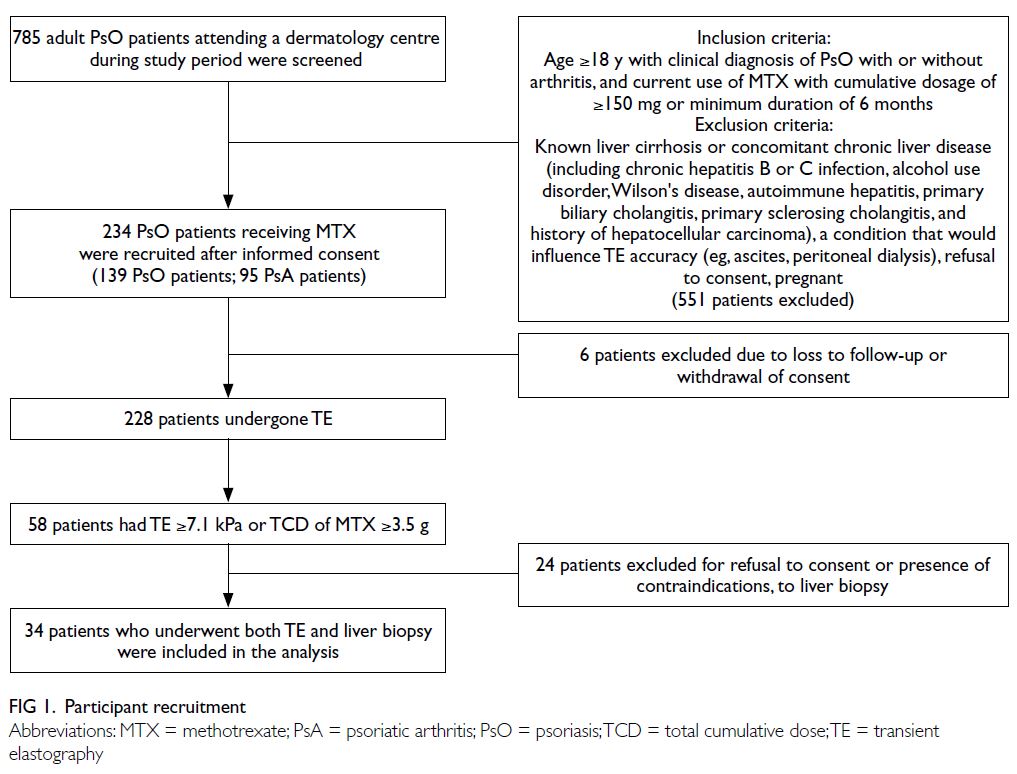

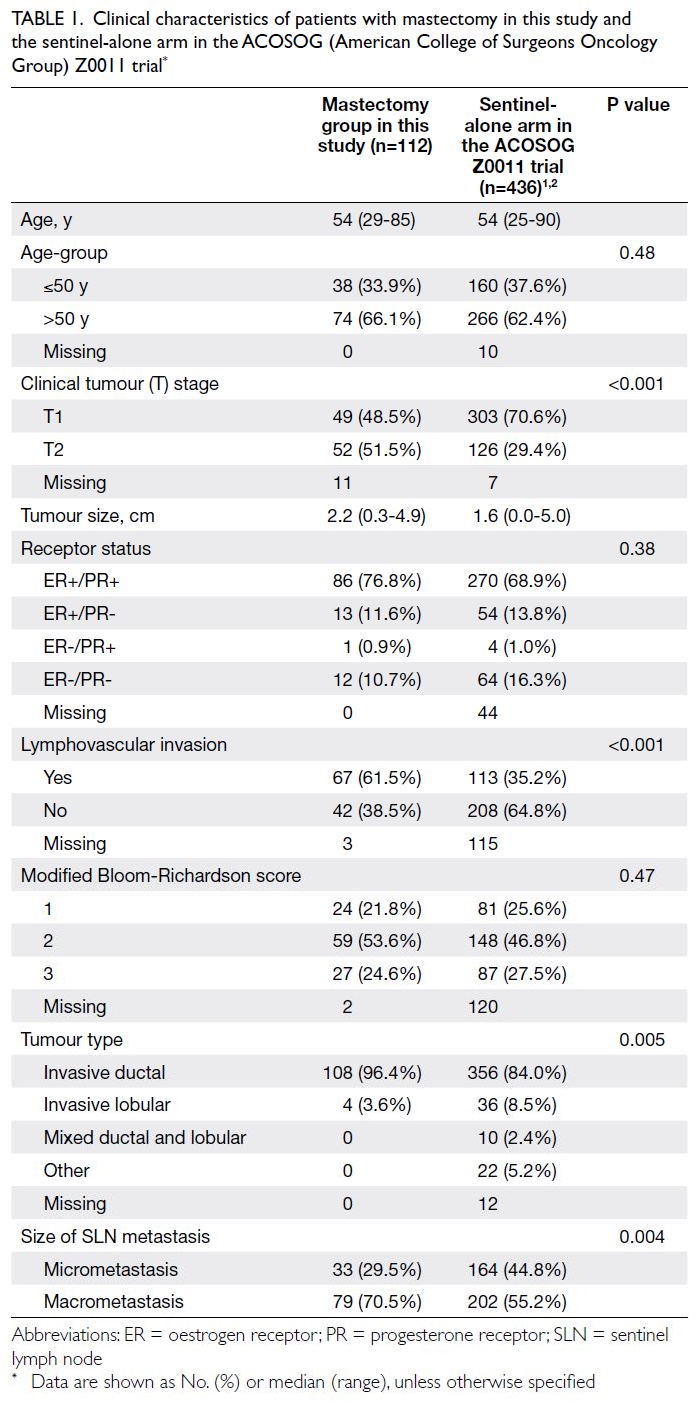

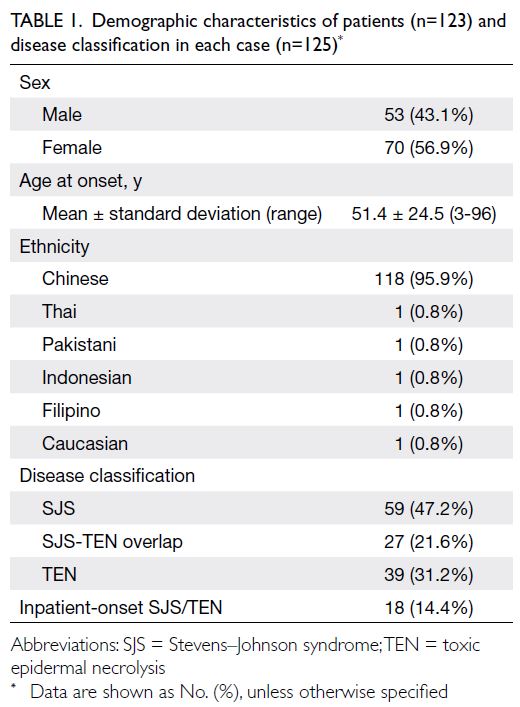

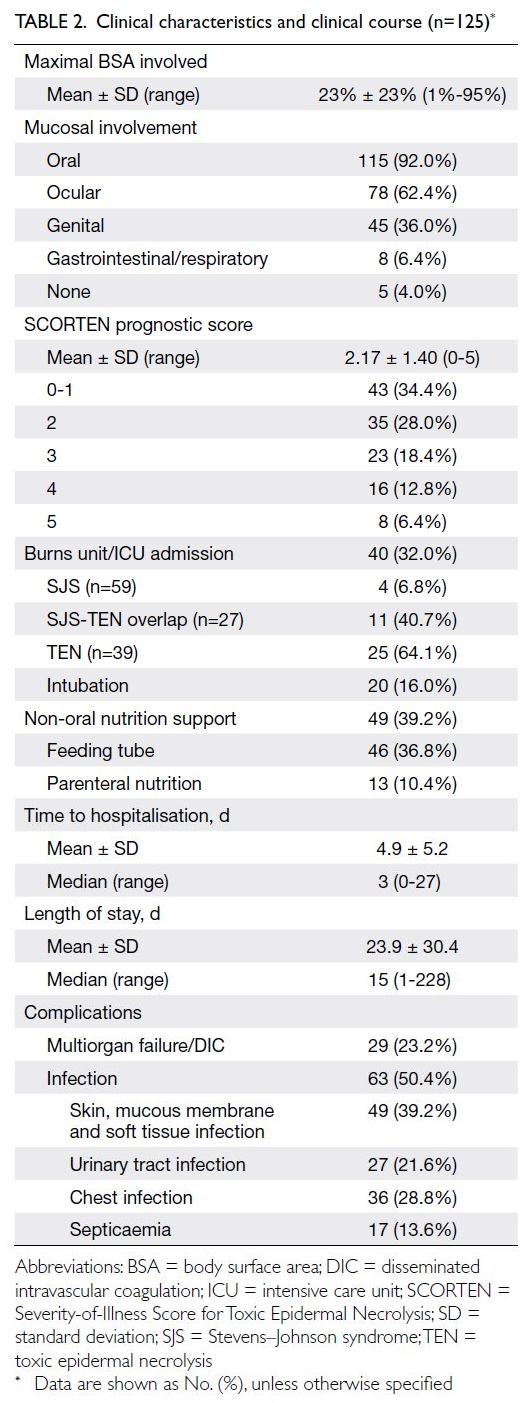

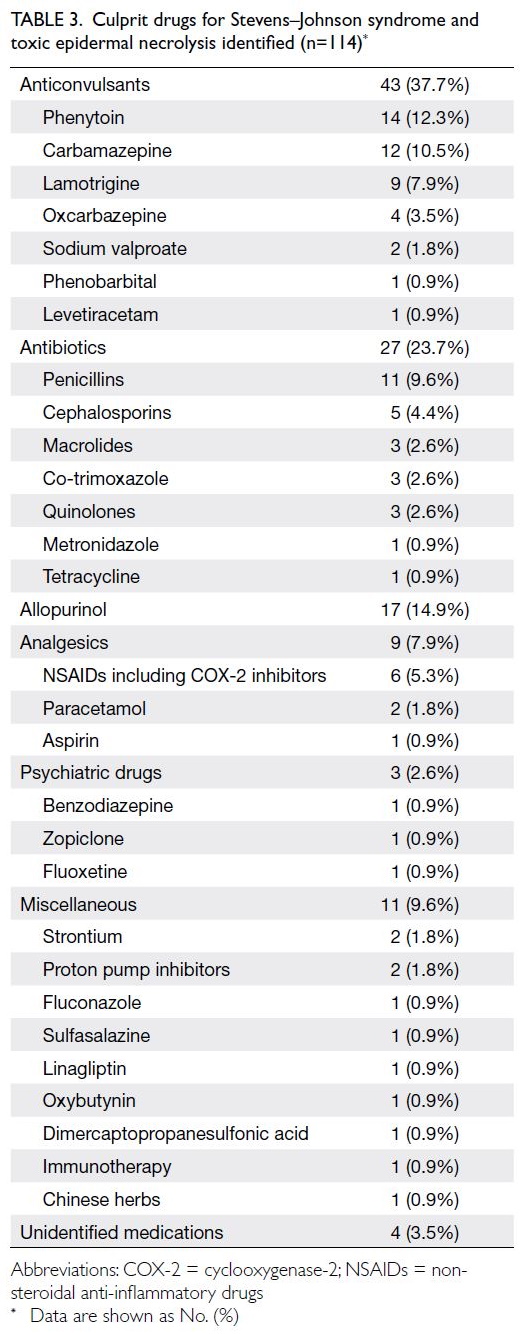

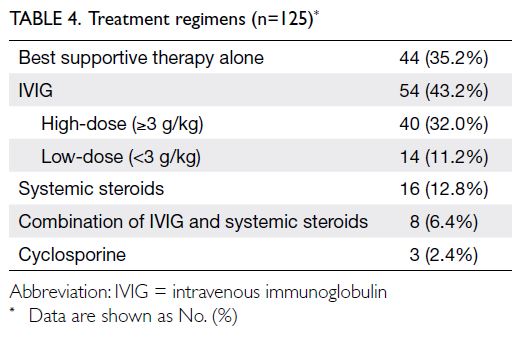

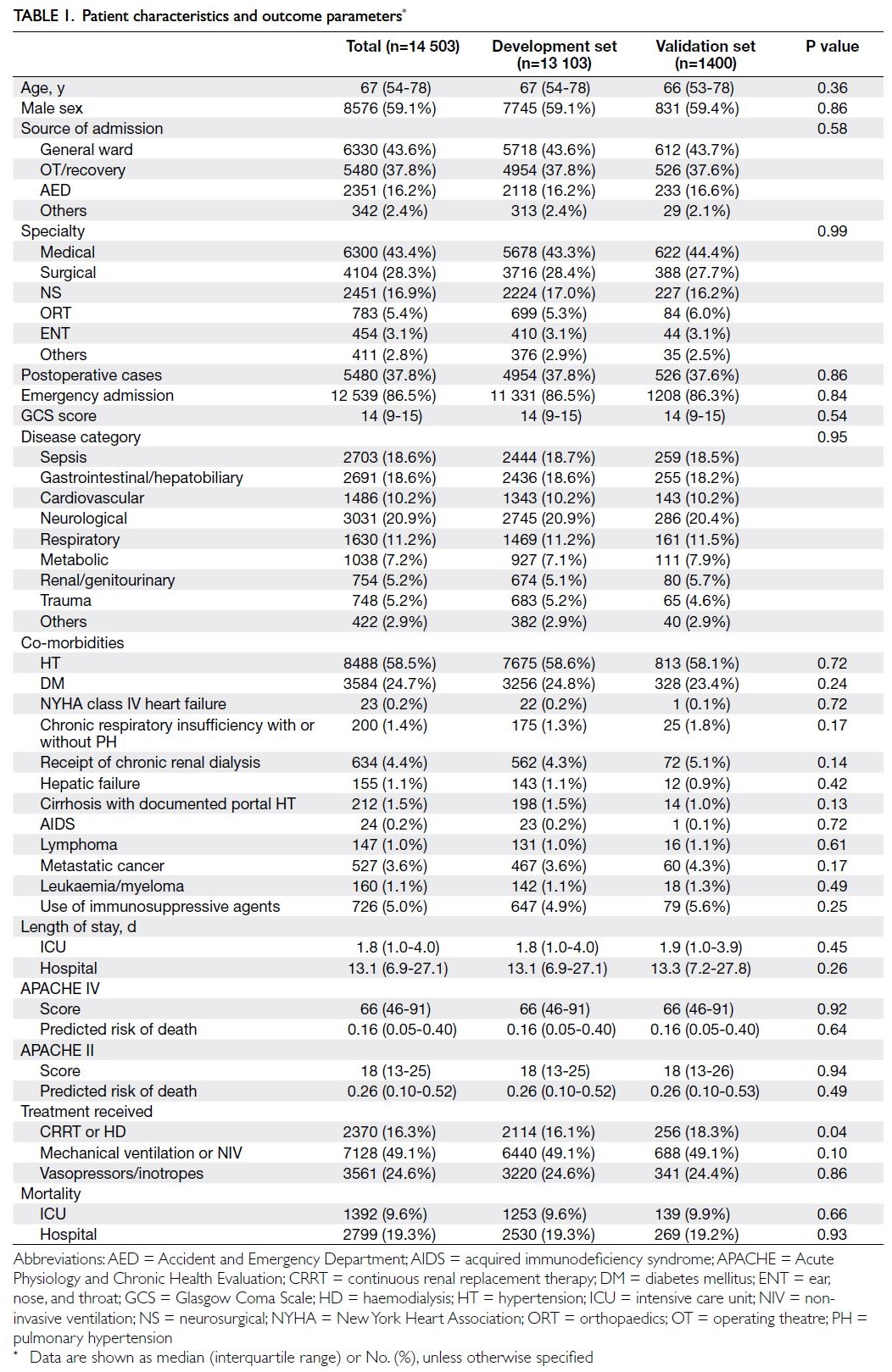

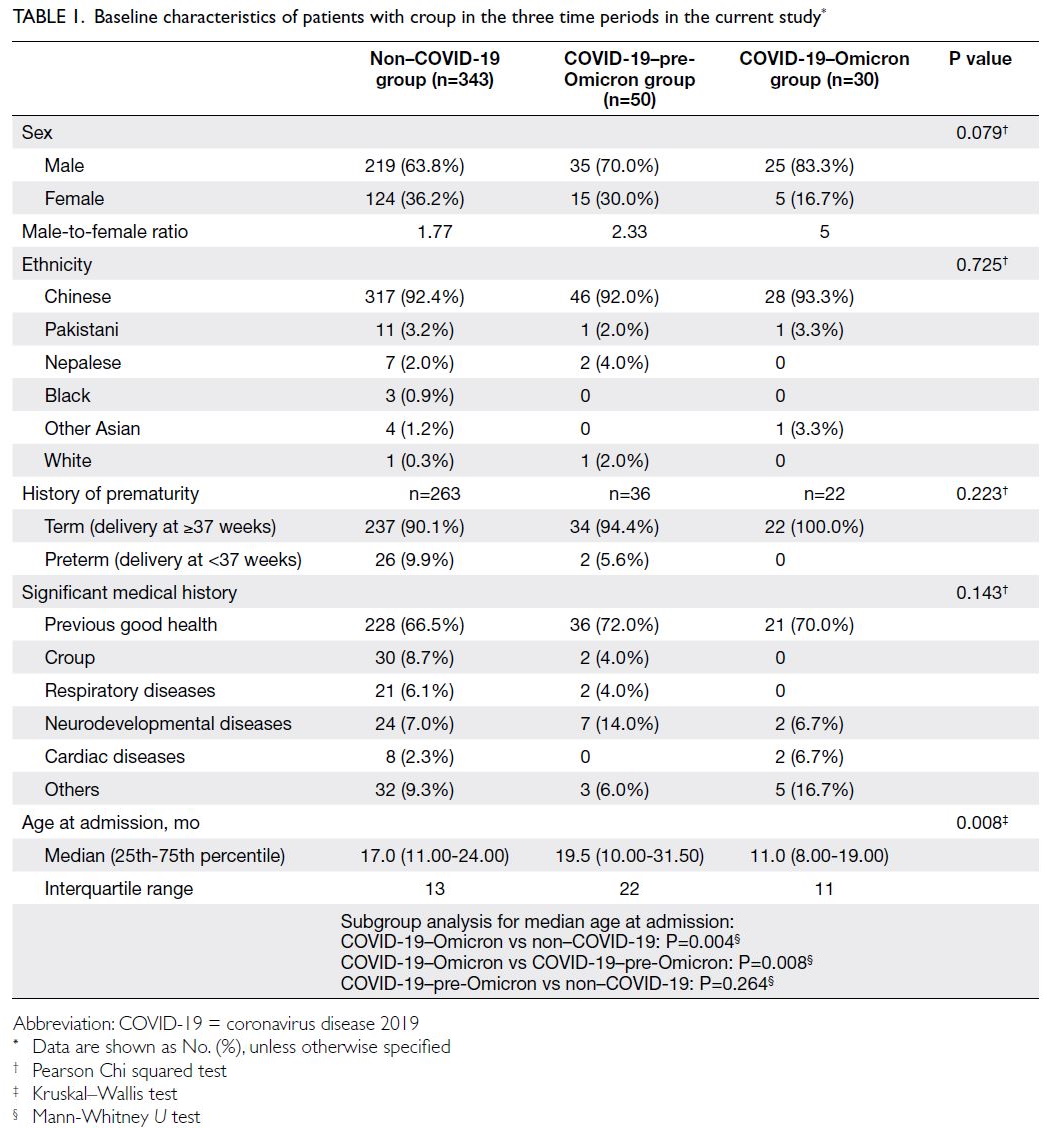

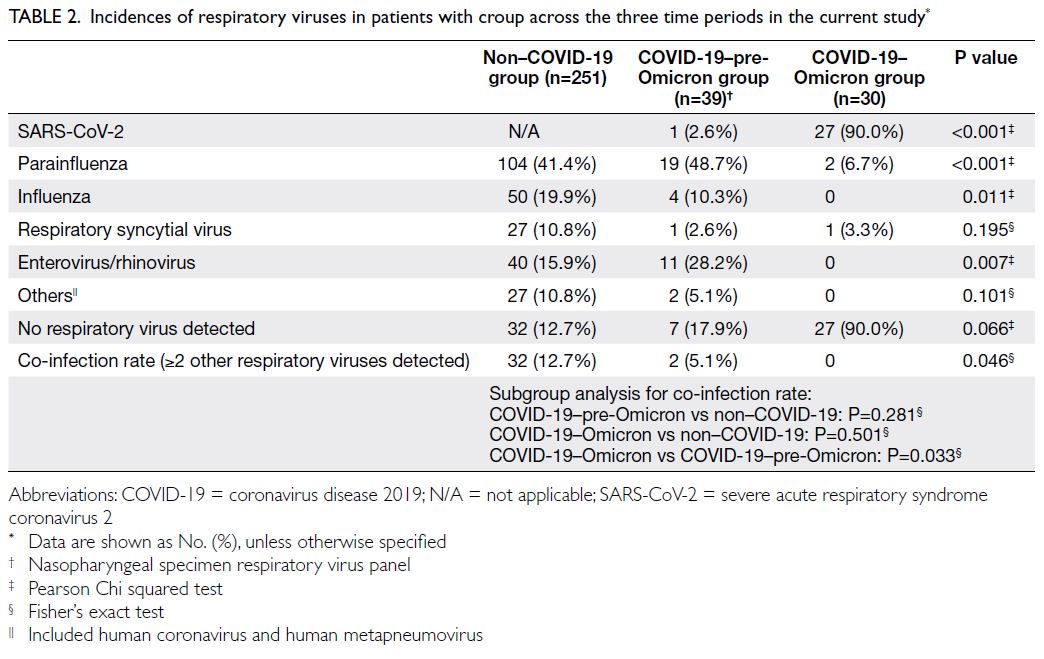

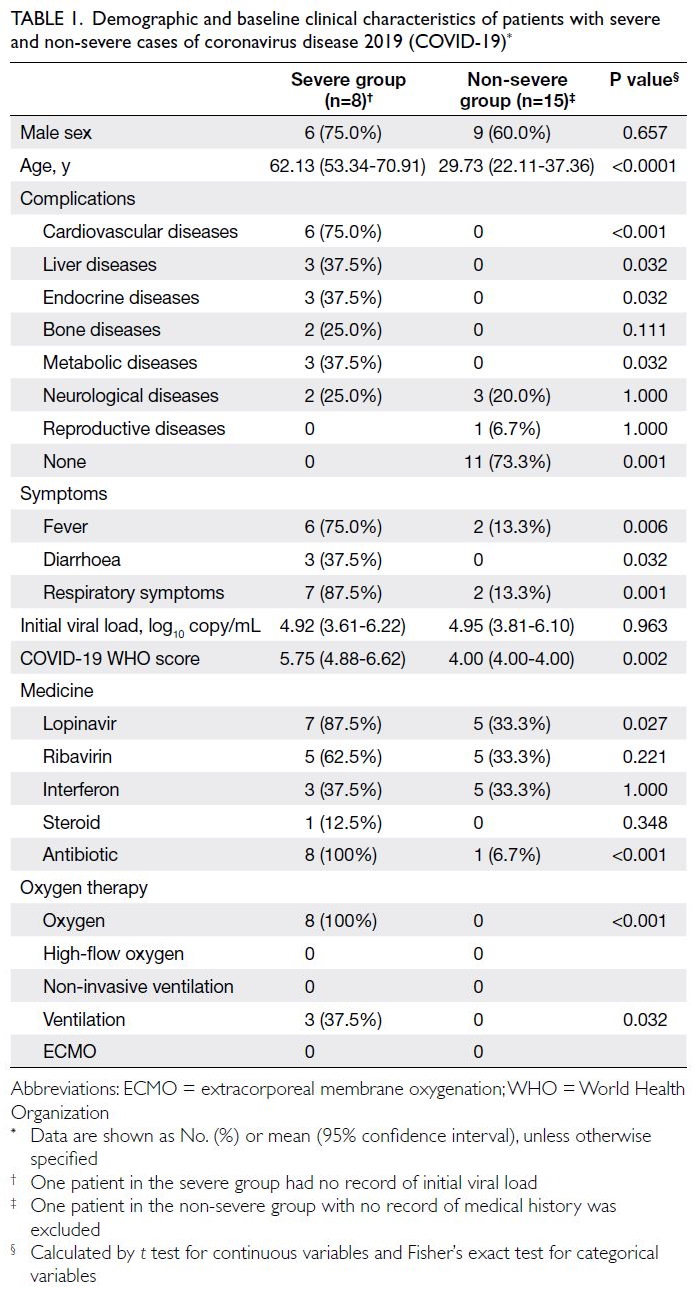

In total, 1662 and 818 participants were included in

the PHS 2014/15 cohort and the PHS 2003/2004

and HHS 2004/2005 cohort, respectively. These

individuals represented populations of 4 445 868

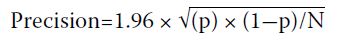

and 3 495 074, respectively. Table 1 shows the

baseline characteristics of the PHS and HHS cohorts

according to Framingham predictors. The mean age was similar in both cohorts (2003-2005: 48.6 years

vs 2014-2015: 50.8 years) and the proportions of

male and female participants were similar (female

participants in 2003-2005: 54.1% vs 2014-2015: 53.0%).

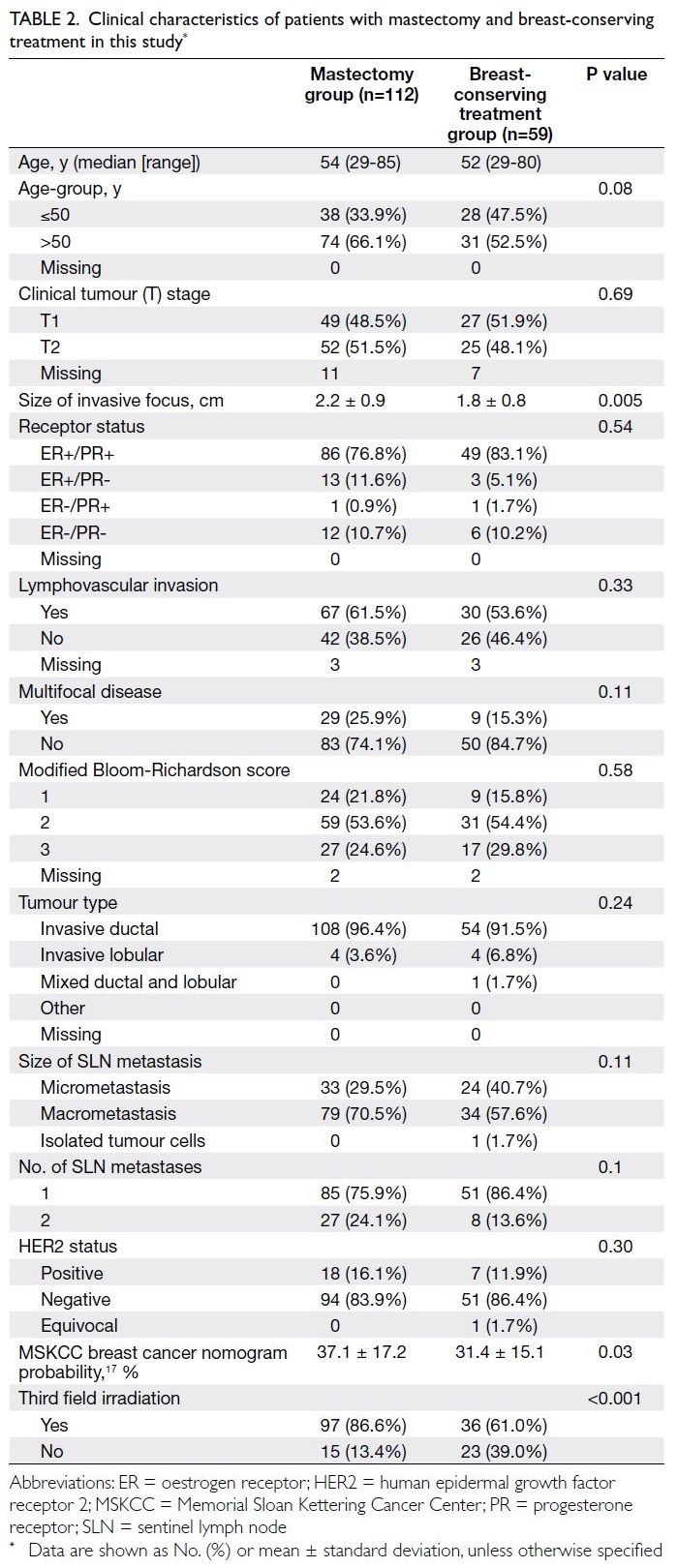

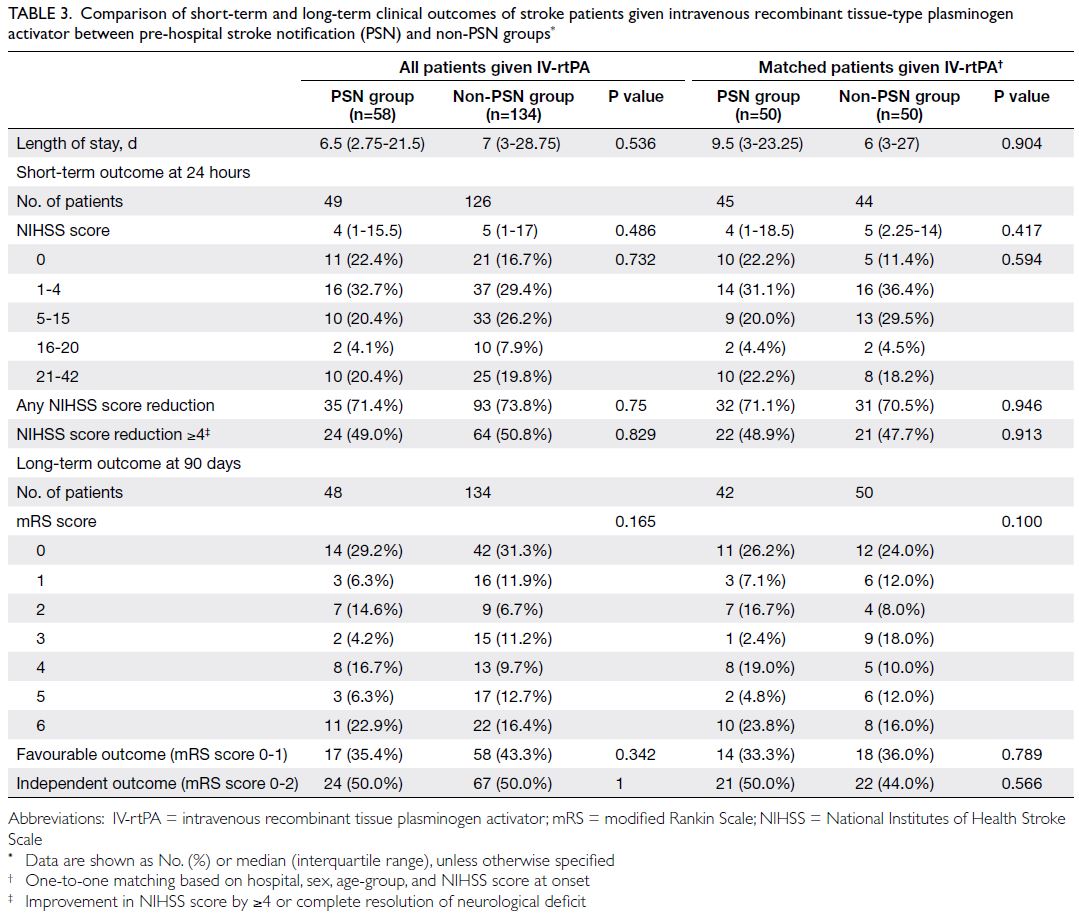

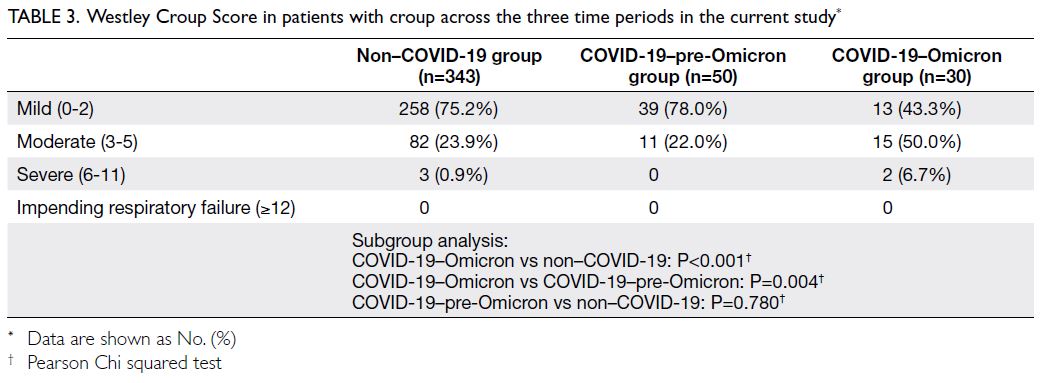

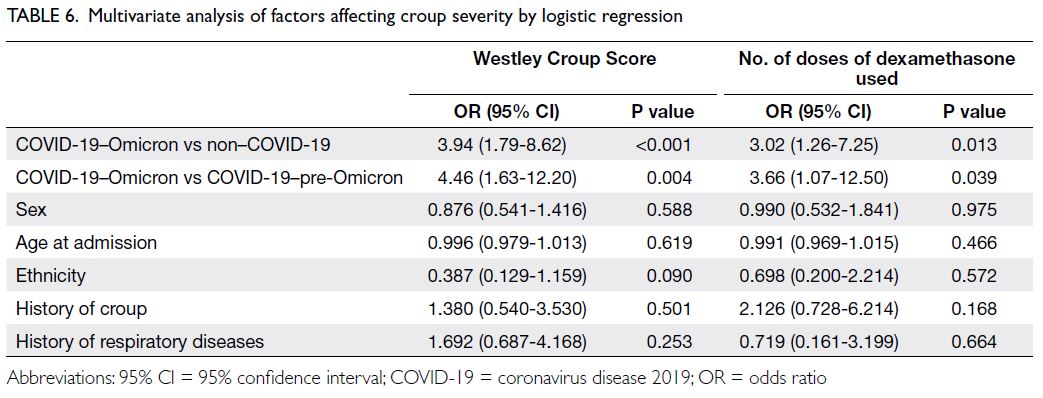

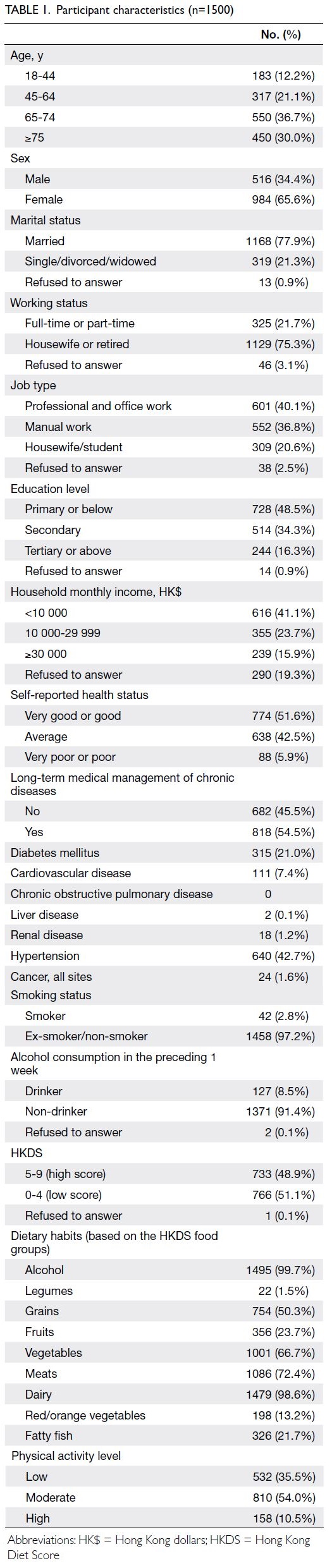

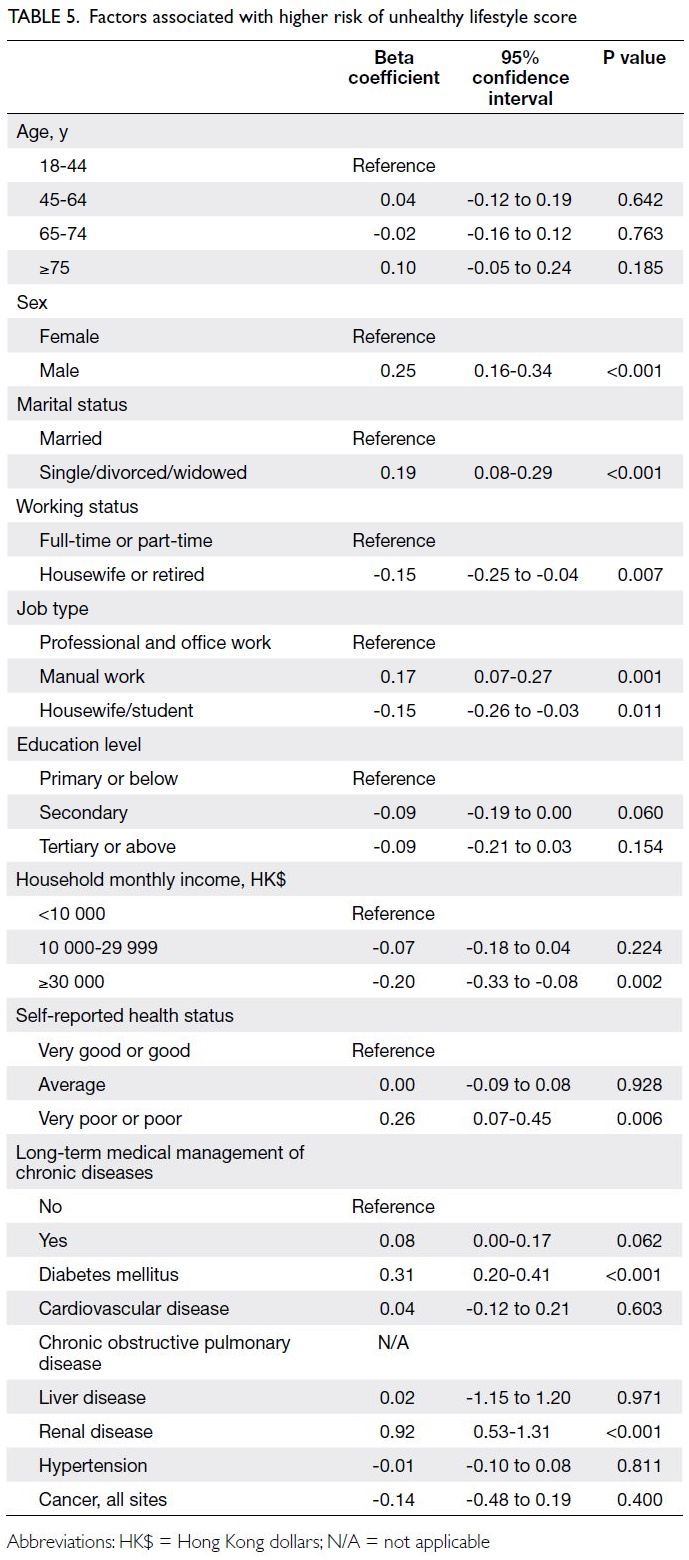

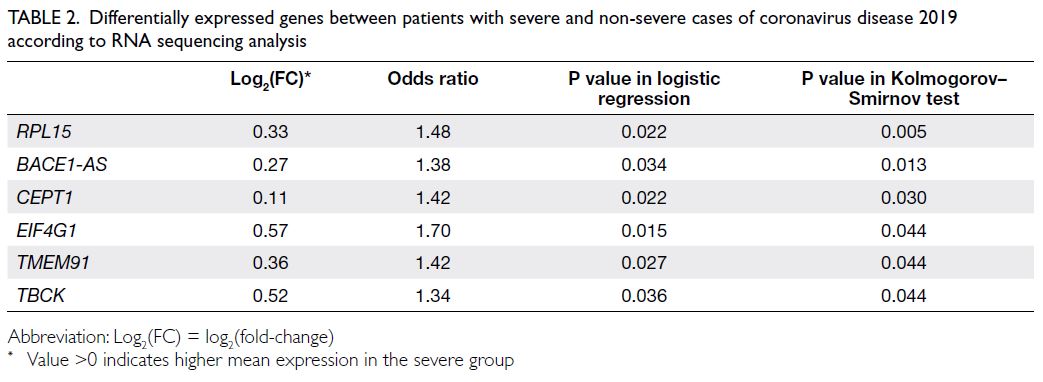

Predicted CVD risk increases with age and is

higher in men (Table 2). In PHS 2003/2004 and HHS

2004/2005, the mean CVD risk increased with age

in both sexes, from 1.6% among women aged 30-44

years to 17.8% among women aged 65-74 years, and

from 5.1% among men aged 30-44 years to 33.4%

among men aged 65-74 years. Between the two

surveys, there was no significant difference in overall

10-year CVD risk (2003-2005: 10.2% vs 2014-2015:

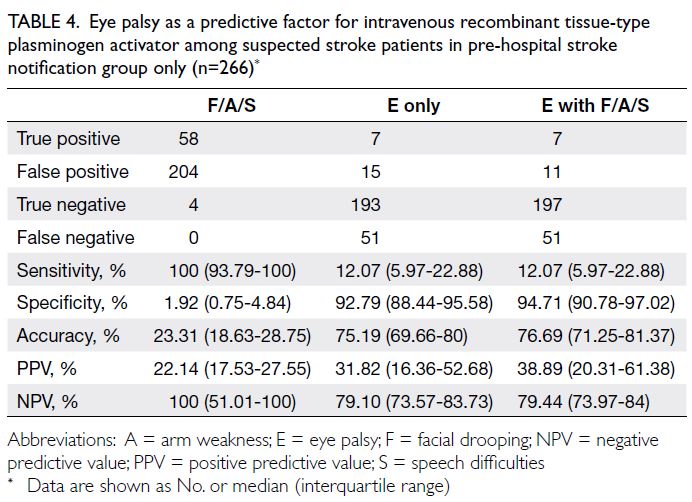

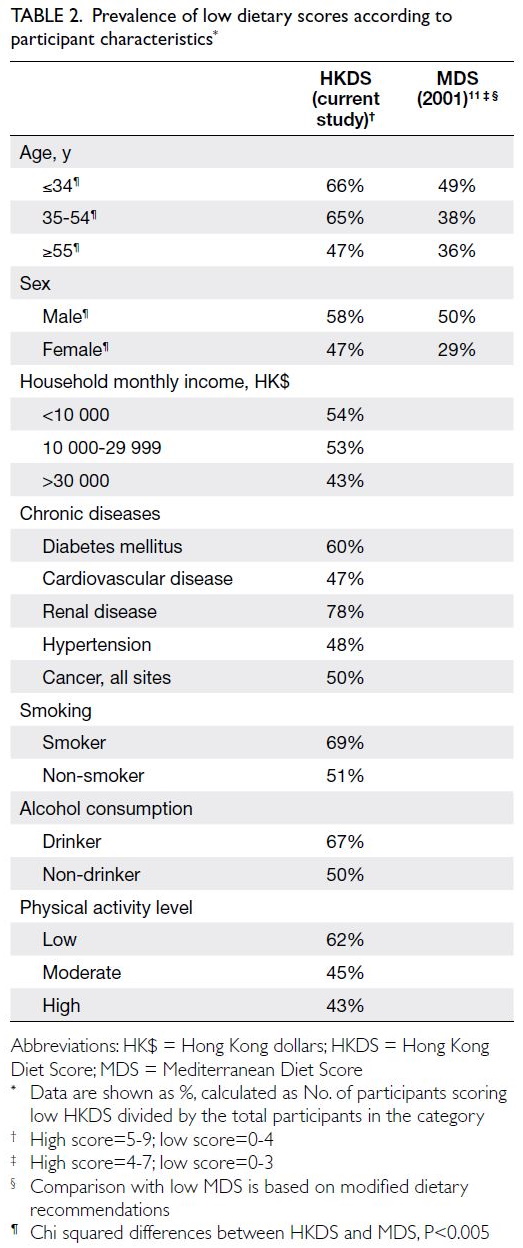

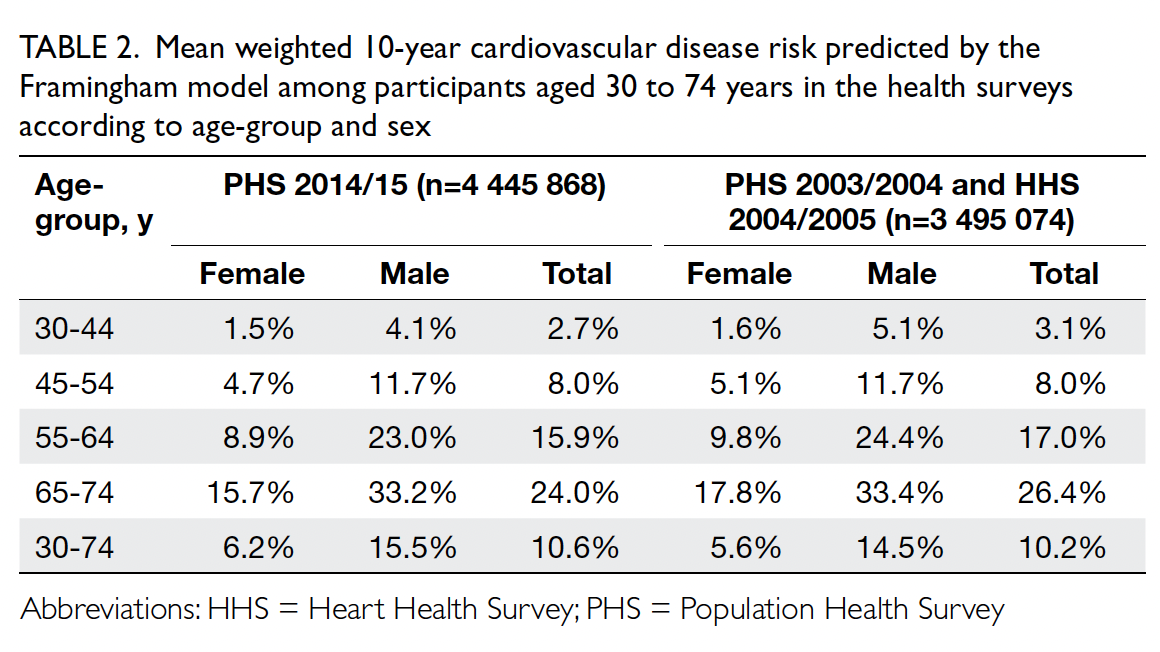

10.6%; P=0.29). After age standardisation according

to WHO world standard population data, the age-standardised

predicted CVD risks in the 2003-2005

cohort and the 2014-2015 cohort were 9.4% and

8.8%, respectively (Table 3). The small decrease

in predicted CVD risk may be due to the decrease

in smokers among men (30.5% vs 24.0%; P<0.001)

[Table 1].

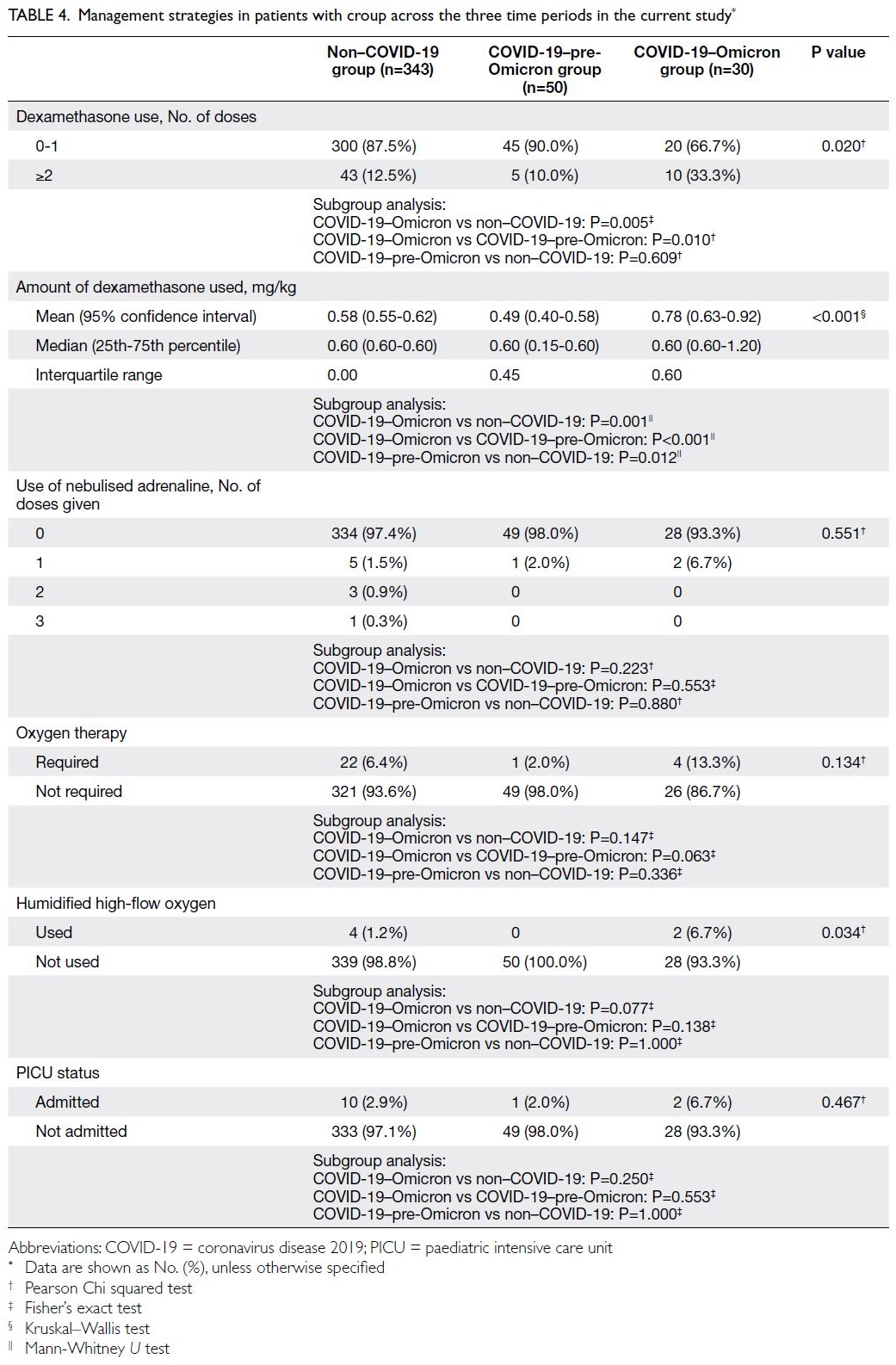

Table 2. Mean weighted 10-year cardiovascular disease risk predicted by the Framingham model among participants aged 30 to 74 years in the health surveys according to age-group and sex

Table 3. Age-standardised estimates of cardiovascular disease risk for the participants of the health surveys

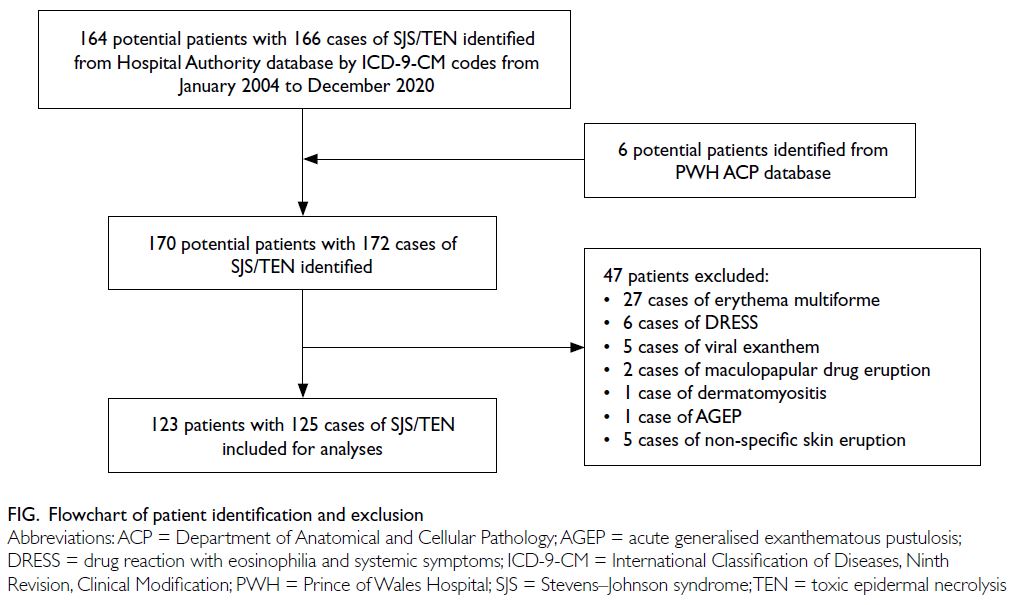

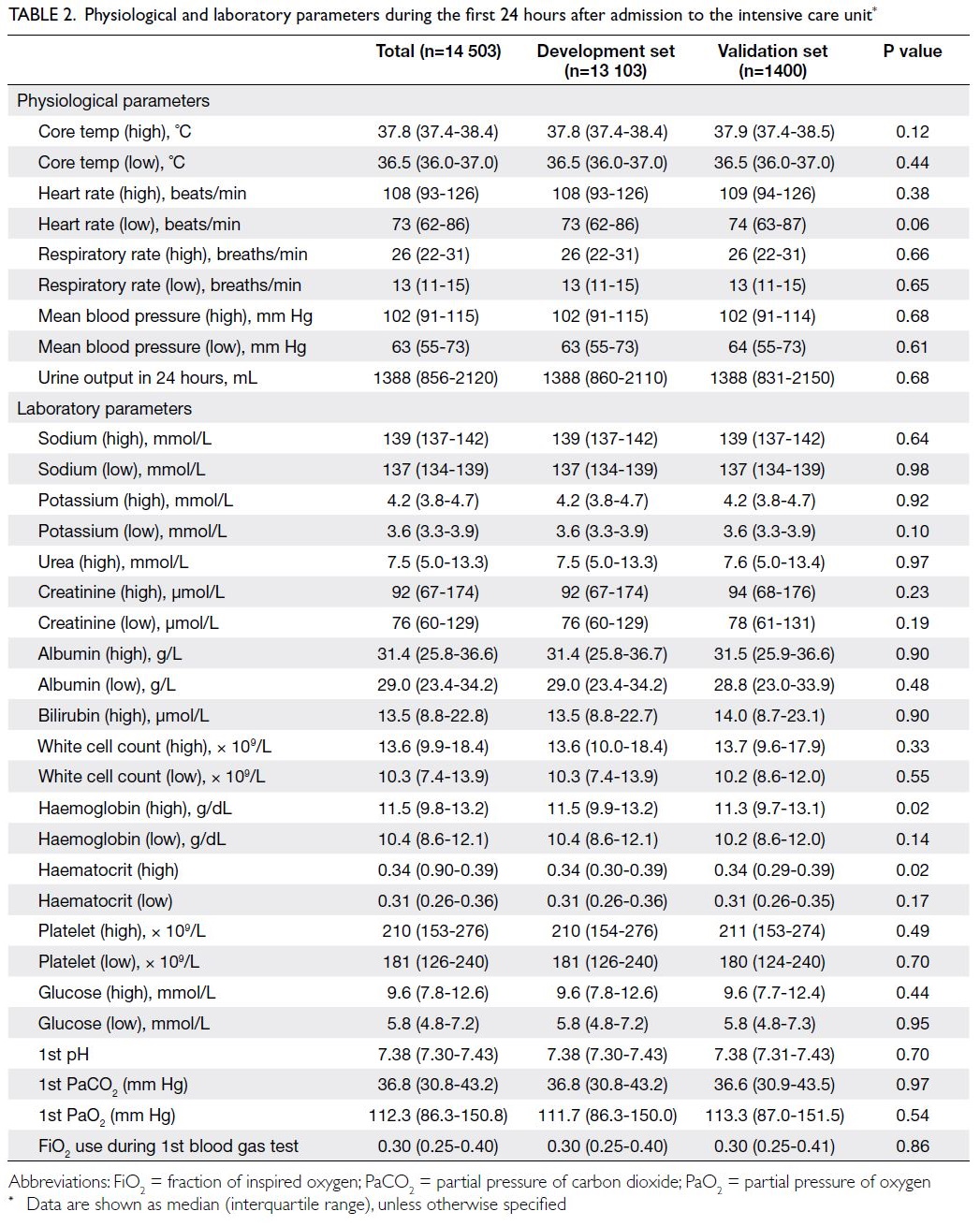

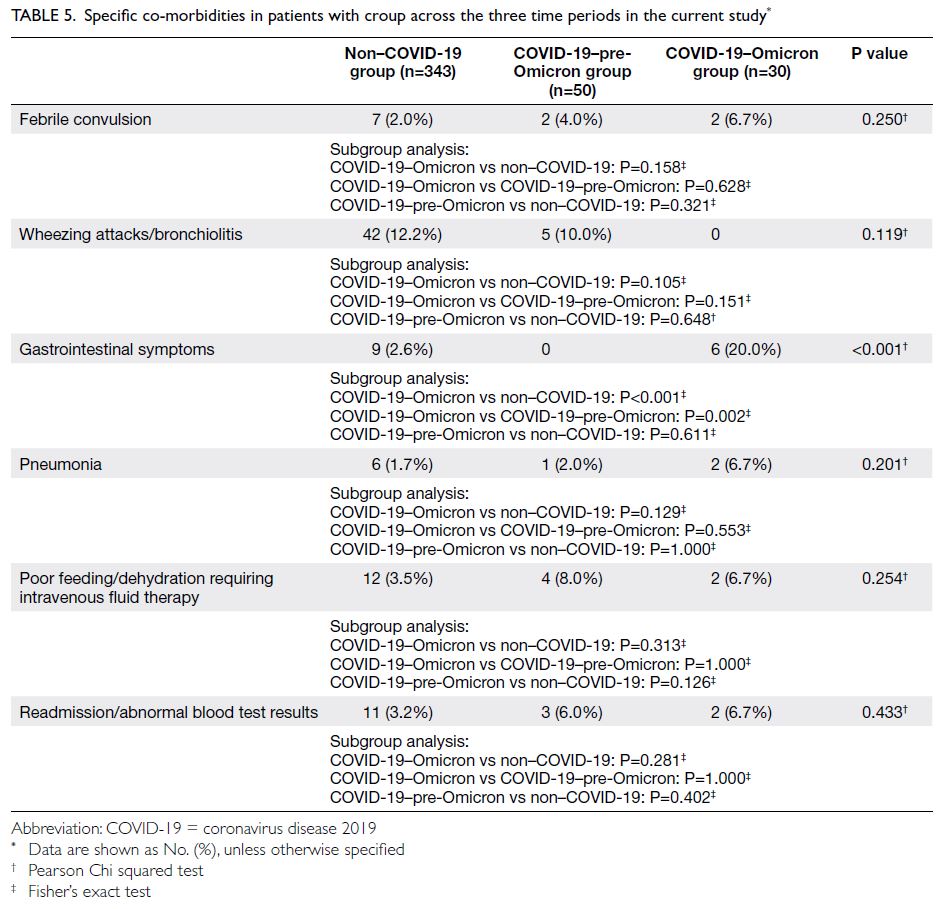

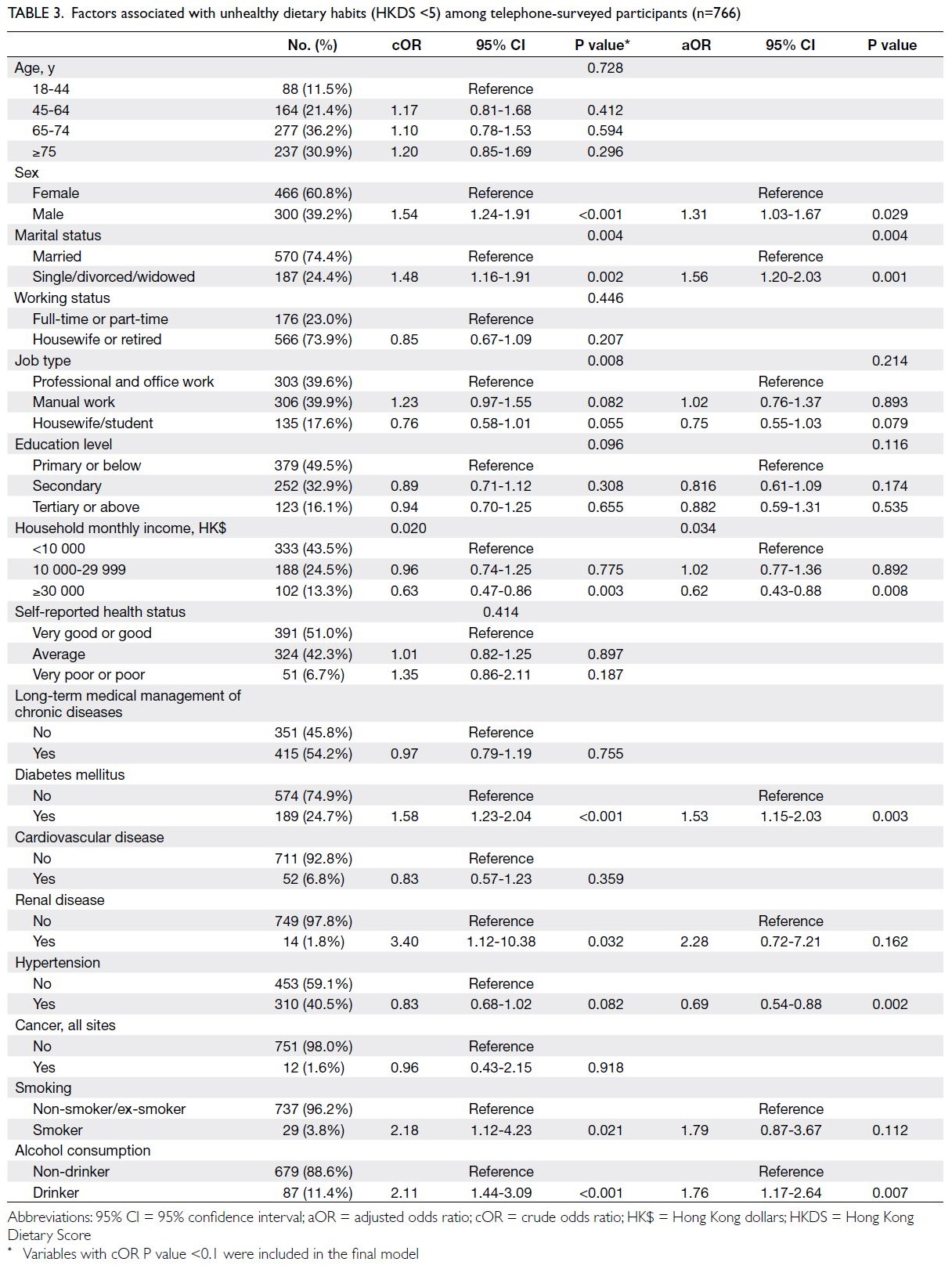

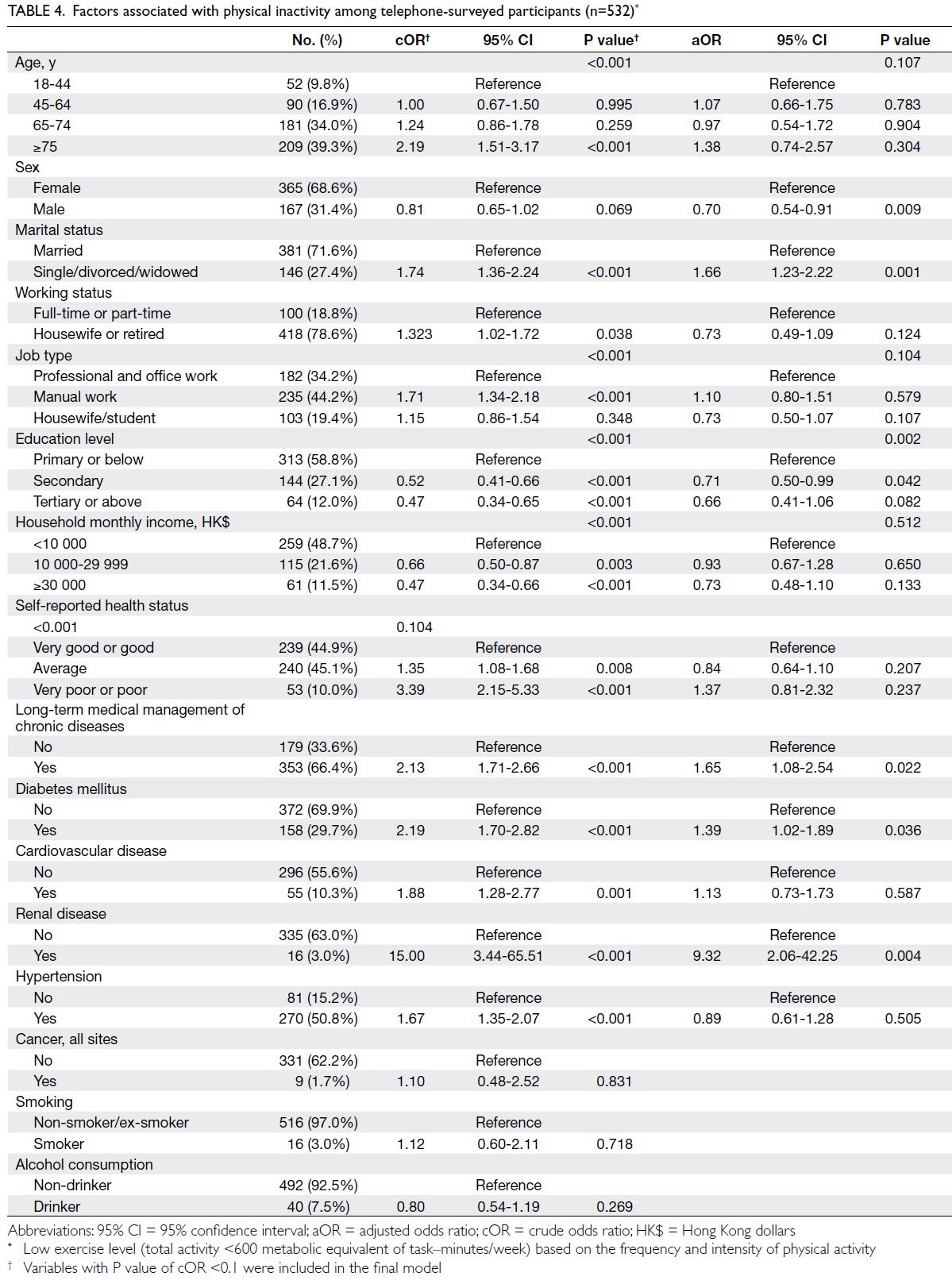

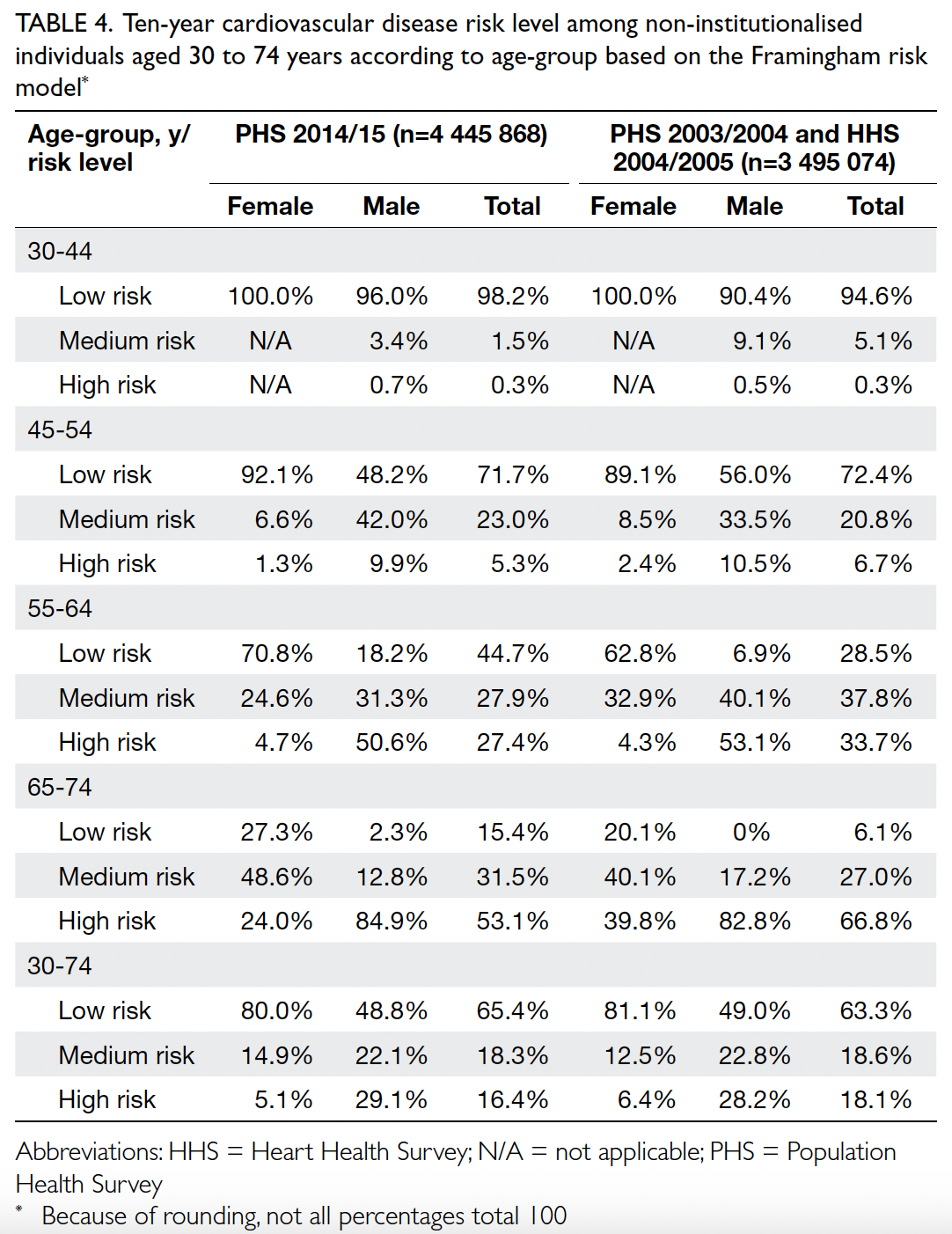

The risk of cardiovascular events over the

next 10 years was classified as low (CVD risk <10%),

medium (CVD risk ≥10% and <20%), and high (CVD

risk ≥20%); the distributions of risk groups are

presented in Table 4. Among participants aged 30 to 74 years, the risk group distributions were similar

in both cohorts. When analysed according to sex,

29.1% of men and 5.1% of women were classified

as high-risk in PHS 2014/15, whereas 28.2% of

men and 6.4% of women were classified as high-risk

in PHS 2003/2004 and HHS 2004/2005. When

analysed according to age-group, more participants

aged 65 to 74 years were classified as high-risk in

PHS 2003/2004 and HHS 2004/2005 (66.8% vs 2014-2015: 53.1%; P=0.028).

Table 4. Ten-year cardiovascular disease risk level among non-institutionalised individuals aged 30 to 74 years according to age-group based on the Framingham risk model

Discussion

Using representative samples from the Hong Kong

PHS and HHS, we found that the 10-year CVD

risk increases with age and is consistently higher

in men (men: 15.5% vs women: 6.2%; P<0.001, in

PHS 2014/15) [Table 2]. This trend is consistent

with previous reports; for example, an analysis

of NHANES (National Health and Nutrition

Examination Survey) III data showed that men have

a significantly higher CVD risk (11.8% in men vs

5.1% in women) and that CVD risk is higher in older

age-groups (16.2% for participants aged 60-74 years

vs 11.2% for participants aged 50-59 years).10 Thus,

risk management for older adults may represent a

challenge to the current health infrastructure. The

burden of CVD is directly associated with increased

morbidity and mortality in patients, and it translates

to substantial healthcare costs. In Hong Kong, the

number of people aged ≥65 years is predicted to

reach 2.58 million (35.9% of the population) by

2064.17 Thus, there is a critical need to achieve a more

comprehensive understanding of the aetiologies

associated with CVD in older adults.

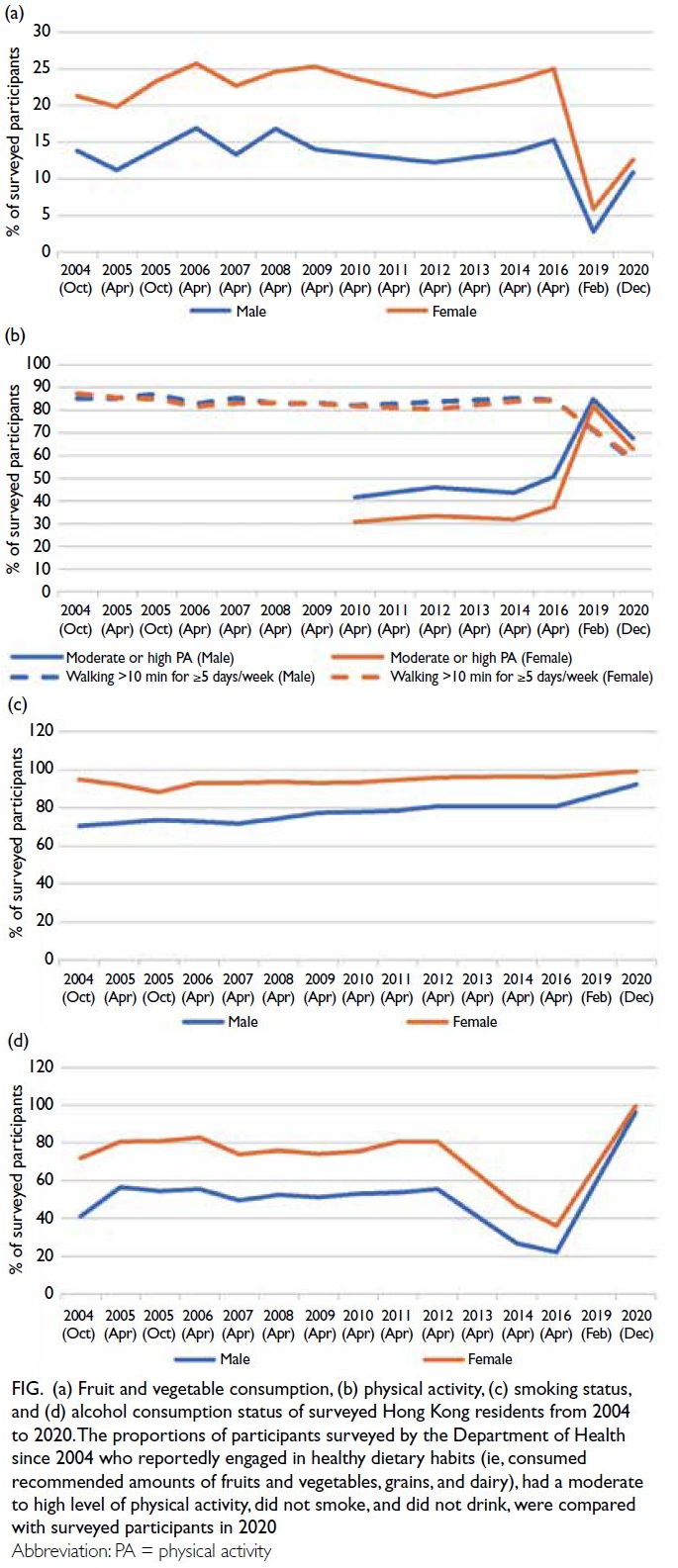

The results have extensive public health

implications. Although age-standardised rates of

death from CVD in Hong Kong greatly decreased

from 93.4 per 100 000 standard population in 2001

to 56.0 per 100 000 standard population in 2017,18

there was no significant difference in overall 10-year

CVD risk between 2003-2005 and 2014-2015 (10.2%

vs 10.6%; P=0.29) [Table 2]. After age standardisation

according to WHO world standard population data, a small decrease in CVD risk was observed, from 9.4% in 2003-2005 to 8.8% in 2014-2015 [Table 3].

A study of NHANES data revealed a similar trend,

consisting of a small decrease in CVD risk from 1988

to 2004 (7.9% to 7.4%; P<0.001).10 The stagnation

in 10-year CVD risk between 2003-2005 and

2014-2015 suggests that despite improvements in

treatment, more effective prevention strategies (eg,

improvements in diet and physical activity levels)

are needed.19 Primary care intervention to manage

modifiable risk factors, such as hypertension,

dyslipidaemia, and diabetes, can complement

population-based policies. Efforts to ensure access to

appropriate healthcare and affordable medications

will help control abnormal risk factor levels.20

Furthermore, despite the importance of targeting

individual risk factors to reduce prevalence, the

long-term objective should be reduced overall risk

of CVD. This objective requires a holistic approach

simultaneously targeting multiple risk factors.

Our results highlight the need for overall risk

assessment, in addition to targeted efforts focused

on specific CVD risk factors. During the past decade,

numerous public health initiatives (eg, smoking

cessation campaigns) have been implemented to

reduce the prevalence of established risk factors for

CVD. It is reasonable to expect that CVD risk would

decrease over time in conjunction with the decreased

prevalences of various risk factors, such as the

declining number of current smokers. Surprisingly,

these changes were not strongly reflected in the

change in 10-year CVD risk. One explanation is that

decreases in the prevalence of some risk factors are

offset by increases in others. For example, population

ageing in Hong Kong may shift more adults into the

high-risk group. However, because the Framingham

model was limited to individuals aged 30 to 74 years,

the change in mean age between the two surveys

is inconsequential. Other possible changes in risk

factors include increases in the prevalence of diabetes

and hypertension, as reflected by the increased

proportion of participants receiving antihypertensive

medications (Table 1). Although CVD mortality

has considerably decreased, it is concerning that

CVD risk has not substantially diminished over the

past decade. This lack of improvement in CVD risk

may lead to an increasing community burden of

CVD in the near future, especially in the context of

population ageing.

The overall 10-year CVD risk for participants

aged 30 to 74 years in 2003-2005 after age adjustment

to US census population data in 2000 was 10.7%.

During a similar time period (1999-2004), the US

population had a 10-year CVD risk of 7.4%.10 When

Hong Kong men were stratified according to risk

group in 2014-2015, 48.8% were classified as low-risk,

22.1% were classified as medium-risk, and

29.1% were classified as high-risk (Table 4). For

comparison, among men in the United Kingdom population during 2012, 46.5% were classified as

low-risk, 39.9% were classified as medium-risk, and

13.6% were classified as high-risk using the National

Institute for Health and Care Excellence Framingham

risk model.21 In terms of risk distribution, a greater

proportion of Hong Kong men were classified as

high-risk compared with men in the United Kingdom

in the early 2010s. In terms of age-standardised risk,

the Hong Kong population had a higher 10-year

CVD risk than the US population in 2003.

Analysis according to age showed that the

proportion of low-risk participants increased from

2003-2005 to 2014-2015, particularly in the age-groups

of 55-64 and 65-74 years (2003-2005: 28.5%

vs 2014-2015: 44.7% for participants aged 55-64

years, and 6.1% vs 15.4% for participants aged 65-74

years) [Table 4]. This increased proportion may be

the result of primary care clinicians recognising

age as a prominent risk factor for CVD, leading to

more aggressive treatment of modifiable risk factors.

Furthermore, there were fewer male smokers in 2014-2015 than in 2003-2005 (24.0% vs 30.5%; P<0.001) [Table 1], suggesting that the success of

recent anti-smoking campaigns also contributed to

this paradigm shift.

Contrary to a previous report addressing

changes in several CVD risk factors,22 we used the

widely validated Framingham risk model to predict

the risk of CVD. By measuring the net change in

cardiovascular risk, we more comprehensively

estimated the impacts of prevention strategies; this

is particularly important because some risk factors

worsened, some improved, and some remained

stable over time. To our knowledge, this is the first

study to evaluate the change in 10-year CVD risk in

an Asian population. The results reinforce the need

for more aggressive community-wide and clinic-based

preventions, with an emphasis on increased

exercise hours during leisure time, dietary changes

that promote higher intake of vegetables and

fruits, as well as lower intake of salt and saturated

fats, weight maintenance, and smoking cessation.

The findings also suggest that the discovery and

use of lipid-lowering drugs and antihypertensive

medications does not effectively translate into

overall risk reduction in an Asian population, unless

these treatments are simultaneously paired with

prevention strategies targeting CVD risk factors.

Strengths and limitations

This study was based on two Hong Kong population

health surveys, and thus the sample is highly

representative of the general population. Baseline

data were collected through laboratory tests and

face-to-face interviews, suggesting that these data

are highly reliable. The long interval between the

two health surveys (2003-2005 to 2014-2015) also

provides insights regarding the effectiveness of

current CVD prevention strategies. Limitations of

the current study involve its use of the Framingham

risk prediction model and the PHS and HHS. Similar

to other surveys, the PHS and HHS are susceptible

to participation bias because the sample data might

not provide an accurate representation of the overall

population. Many PHS variables are self-reported

and may lead to reporting bias. Considering the

effort required to complete the long questionnaires,

the collected data may be susceptible to non-response

bias and recall bias. Furthermore, because

the Framingham cohort primarily consisted of

Caucasians, the predicted 10-year CVD risk in

the Hong Kong population calculated using the

Framingham model should be interpreted cautiously.

The Framingham risk model was developed for

people without a history of CVD; thus, a small

proportion of the overall sample lacking a history

of CVD might have been included in the study,

causing inaccuracies in the results. Additionally, the

model may overestimate the 10-year CVD risk for men in Hong Kong,14 and a recalibrated model with

greater predictive power may be required. Although

several limitations and assumptions may hinder the

prediction of CVD risk, these potential sources of

bias were present in both surveys. Therefore, the

effects of such biases may be less important when

comparing the change in predicted 10-year CVD

risk between the two time points.

Conclusion

During the period from 2003-2005 to 2014-2015,

the change in predicted 10-year CVD risk was not

statistically significant. However, the proportion of

low-risk participants within older age-groups was

higher in PHS 2014/15 than in PHS 2003/2004 and

HHS 2004/2005. More aggressive CVD prevention

strategies and primary care interventions are needed

to address CVD risk factors.

Author contributions

Concept or design: BMY Cheung, CLK Lam.

Acquisition of data: BYC Sung, EHM Tang, BMY Cheung, CLK Lam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: BYC Sung, EHM Tang.

Drafting of the manuscript: BYC Sung, EHM Tang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: L Bedford, CKH Wong, ETY Tse, EYT Yu, BMY Cheung, CLK Lam.

Acquisition of data: BYC Sung, EHM Tang, BMY Cheung, CLK Lam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: BYC Sung, EHM Tang.

Drafting of the manuscript: BYC Sung, EHM Tang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: L Bedford, CKH Wong, ETY Tse, EYT Yu, BMY Cheung, CLK Lam.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As advisers of the journal, CKH Wong and EYT Yu were not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the Department of Health of the Hong

Kong SAR Government for granting approval to use the data

from Population Health Survey 2003/2004, Heart Health

Survey 2004/2005, and Population Health Survey 2014/15

for this research. The authors also thank Dr Weinan Dong and

Ms Tingting Wu from the Department of Family Medicine

and Primary Care of The University of Hong Kong for their

assistance in data interpretation and revising the final draft of

the manuscript.

Declaration

Part of this study was presented as a poster at the ESC Congress

2021 – The Digital Experience (virtual), 27-30 August 2021,

and was published as an abstract (Sung BY, Tang EH, Bedford

L, et al. Change in Framingham cardiovascular disease risk

between 2003 and 2014 in the Hong Kong Population Health

Survey [abstract]. Eur Heart J 2021;42:1).

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The requirement for ethics approval for this research was waived by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster,

Hong Kong as this study involved secondary analysis of de-identified

governmental data.

References

1. Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, et al. Global, regional,

and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10

causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1-25. Crossref

2. GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional,

and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes

of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a

systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study

2017. Lancet 2018;392:1736-88. Crossref

3. Romero CX, Romero TE, Shlay JC, Ogden LG, Dabelea D.

Changing trends in the prevalence and disparities of

obesity and other cardiovascular disease risk factors in

three racial/ethnic groups of USA adults. Adv Prev Med

2012;2012:172423. Crossref

4. World Health Organization. Hypertension. 2019. Available

from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

5. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P,

Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis

of worldwide data. Lancet 2005;365:217-23. Crossref

6. Lin X, Xu Y, Pan X, et al. Global, regional, and national

burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and

territories: an analysis from 1990 to 2025. Sci Rep

2020;10:14790. Crossref

7. World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases.

2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

8. World Health Organization. Prevention of cardiovascular

disease. Guidelines for assessment and management of

cardiovascular risk. 2007. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43685/9789241547178_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

9. Ajani UA, Ford ES. Has the risk for coronary heart disease changed among U.S. adults? J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:1177-82. Crossref

10. Lopez-Jimenez F, Batsis JA, Roger VL, Brekke L, Ting HH,

Somers VK. Trends in 10-year predicted risk of

cardiovascular disease in the United States, 1976 to 2004.

Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009;2:443-50. Crossref

11. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government;

Department of Community Medicine, The University

of Hong Kong. Population Health Survey 2003/2004 2015. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/report_on_population_health_survey_2003_2004_en.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

12. Surveillance and Epidemiology Branch, Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Report of Population Health Survey 2014/2015. 2017. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2014_15_full_report_eng.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

13. D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General

cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the

Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117:743-53. Crossref

14. Lee CH, Woo YC, Lam JK, et al. Validation of the Pooled Cohort equations in a long-term cohort study of Hong Kong Chinese. J Clin Lipidol 2015;9:640-6.e2. Crossref

15. World Health Organization. Age standardization of rates:

a new WHO standard. 2001. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/global-health-estimates/gpe_discussion_paper_series_paper31_2001_age_standardization_rates.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2024.

16. United States Census Bureau. Introduction to Census 2000

Data Products. Available from: https://usa.ipums.org/usa/resources/voliii/pubdocs/2000/mso-01icdp.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2024.

17. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Hong Kong population projections 2017-2066. 2017. Available from: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/media_workers_corner/pc_rm/hkpp2017_2066/index.jsp. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

18. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Non-Communicable Diseases Watch. Overview of

cardiovascular diseases. September 2018. Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/ncd_watch_sep_2018.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

19. National Prevention Council, United States Government.

National Prevention Strategy. America’s plan for better

health and wellness. June 2011. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/disease-prevention-wellness-report.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan 2021.

20. Chow CK, Nguyen TN, Marschner S, et al. Availability and

affordability of medicines and cardiovascular outcomes

in 21 high-income, middle-income and low-income

countries. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002640. Crossref

21. Collins GS, Altman DG. Predicting the 10-year risk of

cardiovascular disease in the United Kingdom: independent

and external validation of an updated version of QRISK2.

BMJ 2012;344:e4181. Crossref

22. Carroll MD, Lacher DA, Sorlie PD, et al. Trends in serum lipids and lipoproteins of adults, 1960-2002. JAMA 2005;294:1773-81. Crossref