COVID-19 vaccination and transmission patterns among pregnant and postnatal women during the fifth wave of COVID-19 in a tertiary hospital in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Med J 2024 Feb;30(1):16–24 | Epub 16 Jan 2024

https://doi.org/10.12809/hkmj2210249

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

COVID-19 vaccination and transmission patterns among pregnant and postnatal women during the fifth wave of COVID-19 in a tertiary hospital in Hong Kong

PW Hui, MD, FRCOG; LM Yeung, BNur, MPH; Jennifer KY Ko, MB, BS, MRCOG; Theodora HT Lai, MB, BS, MRCOG; Diana MK Chan, MB, BS, MRCOG; Dorothy TY Chan, MB, BS; Sophia YK Mok, MB, BS, MRCOG; Kitty KW Ma, MB, BS; Pamela SY Kwok, BNur, MSM, Polly WC Pang, BN; Mimi TY Seto, MB, BS, MRCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr PW Hui (apwhui@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Vaccination is a key strategy to

control the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

pandemic. Safety concerns strongly influence

vaccine hesitancy. Disease transmission during

pregnancy could exacerbate risks of preterm birth

and perinatal mortality. This study examined

patterns of vaccination and transmission among

pregnant and postnatal women during the fifth wave

of COVID-19 in Hong Kong.

Methods: The Antenatal Record System and Clinical

Management System of the Hospital Authority

was used to retrieve information concerning the

demographic characteristics, vaccination history,

COVID-19 status, and obstetric outcomes of

women who were booked for delivery at Queen

Mary Hospital in Hong Kong and had attended the

booking antenatal visit from 1 July 2021 to 30 June

2022.

Results: Among 2396 women in the cohort, 2006

(83.7%), 1843 (76.9%), and 831 (34.7%) had received

the first, second, and third doses of COVID-19

vaccine, respectively. Among 1012 women who

had received the second dose, 684 (67.6%) women

were overdue for their third dose. There were 265

(11.1%) reported COVID-19 cases. Women aged 20

to 29 years had a low vaccination rate but the highest disease rate (19.1%). The disease rate was more

than tenfold higher in women who had no (20.3%)

or incomplete (18.8%) vaccination, compared

with women who had complete vaccination (2.1%;

P<0.001).

Conclusion: Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination

was low in pregnant women. Urgent measures are

needed to promote vaccination among pregnant

women before the next wave of COVID-19.

New knowledge added by this study

- As of 30 June 2022, only 34.7% of women in Hong Kong had received three doses of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine.

- Two-thirds women scheduled for a third dose of COVID-19 vaccine did not receive the booster dose during pregnancy.

- The disease rate was almost ten times higher in women who had no or incomplete vaccination, compared with women who had complete vaccination.

- Women aged 20 to 29 years had a low vaccination rate but the highest disease rate.

- Pregnant women should receive education concerning the importance and safety of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

- Delayed receipt of booster doses increase susceptibility to COVID-19 during future waves.

- A comprehensive programme incorporating pertussis and COVID-19 vaccination for pregnant women should be considered.

Introduction

Vaccination is an effective tool to combat the

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Two types of COVID-19 vaccines are used in Hong

Kong: the Sinovac-CoronaVac inactivated severe

acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccine

(Sinovac Biotech Ltd, Beijing, China) and Pfizer

BioNTech BNT162b2 (Pfizer Inc, Philadelphia

[PA], United States) messenger RNA vaccine began

distribution on 26 February 2021 and 10 March

2021, respectively.

According to the World Health Organization,

vaccine hesitancy is defined as delaying or refusing

vaccination despite the availability of vaccination

services.1 In a study conducted during the third wave

of COVID-19 in Hong Kong, the overall vaccine

acceptance rate was approximately 37%.2 Although

the subsequent acceptance rate has varied with

pandemic progression, confidence in COVID-19

vaccines has remained a key factor in reducing

vaccine hesitancy.3

Pregnant women were generally excluded

from clinical trials focusing on the development,

safety, and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines.4 When

COVID-19 vaccines were introduced in Hong

Kong, routine vaccination was not recommended

for women who were pregnant or breastfeeding,

except when there was a high risk of exposure or

complications.5 The relative lack of data may have

contributed to vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women.6 7 8 Based on data concerning the efficacy and

safety of COVID-19 vaccination in preventing serious

illness,9 COVID-19 vaccination is recommended for

people who are pregnant, breastfeeding, planning to

become pregnant, or may become pregnant in the

future.10 11

On 23 April 2021, the Hong Kong College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (HKCOG) issued

an interim recommendation that pregnant women

receive the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine at the same

time as the general population.12 On 18 February

2022, the Sinovac vaccine was also recommended

for use in pregnant women.12 Furthermore, the

recommended interval between the second and third

doses of COVID-19 vaccine was shortened from 180

days to 90 days, beginning on 4 March 2022. The

vaccine pass policy for entry to specific premises was

tightened on 31 May 2022.13 For persons who were

over 18 years old and had no history of infection, a

minimal of two doses of vaccination was required.

A third dose was required if the second dose was

taken over 6 months ago. Starting from 13 June 2022,

women attending obstetric clinics were required to

provide a negative result proof of a polymerase chain

reaction–based nucleic acid test conducted with

specimen collected within 48 hours before the visit

if they did not fulfil the vaccine pass requirement.14

The fifth wave of COVID-19 in Hong Kong has

resulted in an overwhelming number of COVID-19

cases. Pregnant women are not automatically

protected from COVID-19; indeed, their vaccine

hesitancy and low vaccination rate may lead to

greater susceptibility. Information concerning the

patterns of COVID-19 vaccination and disease

transmission among pregnant women in Hong

Kong is unavailable. This study examined patterns

of vaccination and transmission among pregnant

women who were booked for delivery at a tertiary

hospital in Hong Kong, with the goal of providing

insights into maternal disease characteristics.

Methods

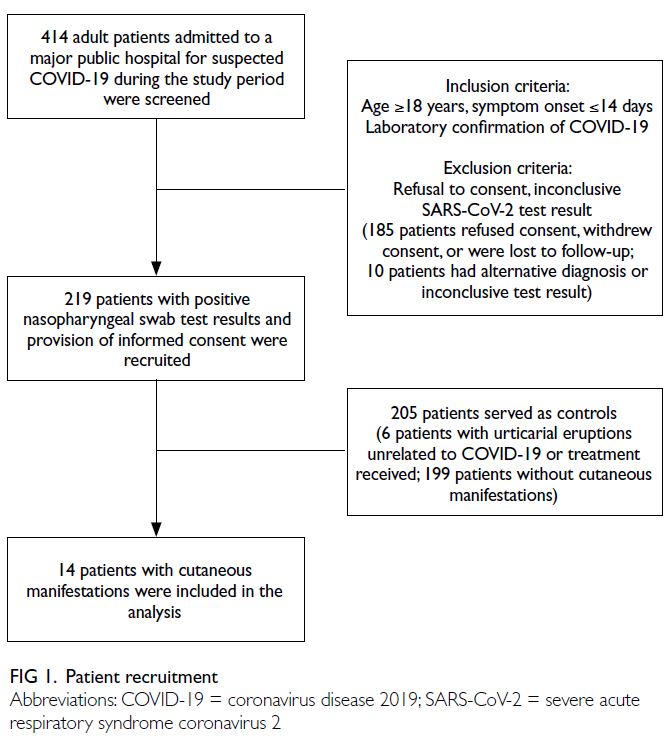

This retrospective review included women who were

booked for delivery at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong

Kong and had attended the booking antenatal visit

from 1 July 2021 to 31 March 2022. Information

concerning COVID-19 vaccination history was

retrieved from the Clinical Management System of

the Hospital Authority, which captured COVID-19

vaccination data from the Department of Health.

Pregnant women were diagnosed with

COVID-19 because of symptoms or (in the absence

of symptoms) during admission screening. Women

diagnosed with COVID-19 through other channels

were able to reschedule their appointments. Phone

consultations were provided by the obstetric team

at Queen Mary Hospital. The clinical details of

COVID-19 cases were documented in the computerised Antenatal Record System.

Additionally, antenatal progress notes were updated

if a pregnant woman reported a history of COVID-19

during a follow-up visit. Data regarding demographic

characteristics, COVID-19 status, and obstetric

outcomes were retrieved from the Antenatal Record

System.

The vaccinated group comprised women who

received at least one dose of any type of COVID-19

vaccine. Vaccination periods were classified as pre-pregnancy,

antenatal, and postnatal for women with

a known date of delivery, miscarriage, or termination

of pregnancy as of 30 June 2022. For women with

ongoing pregnancies and unknown obstetric

outcomes, the vaccination period was estimated

according to the expected date of delivery. Antenatal

status was regarded as known ongoing pregnancy

before 42 weeks of gestation. A vaccination

episode was defined as any episode of COVID-19

vaccination including the first, second, and third

doses. The number of days elapsed since vaccination

was defined as the interval between the last dose of

COVID-19 vaccine and 30 June 2022 for women who

had received one or two doses of vaccine. Complete

vaccination was regarded as the period between

15 and 90 days after the second dose of COVID-19

vaccine, or 14 days after the third dose of COVID-19

vaccine for women who had never been diagnosed

with COVID-19. For women with COVID-19, the

date of diagnosis was regarded as the reference point

when determining vaccination status.

Descriptive statistics were reported.

Vaccination rates were calculated according to age-group.

Background demographic characteristics were

compared between vaccinated and unvaccinated

groups. Student’s t test, analysis of variance, and the

Chi squared test were used as appropriate. Regression

analyses were conducted to identify factors affecting

vaccine acceptance. P values <0.05 were considered

statistically significant. Statistical analyses were

performed using SPSS software (Windows version

26; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Results

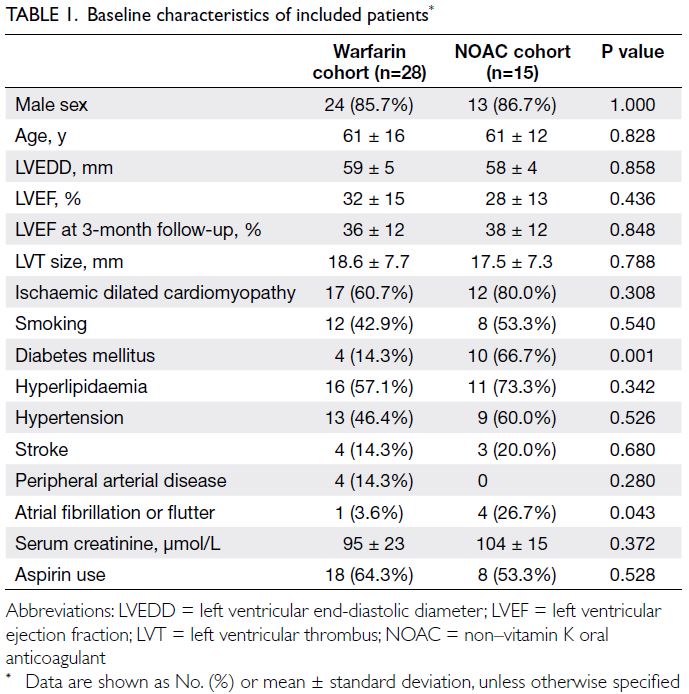

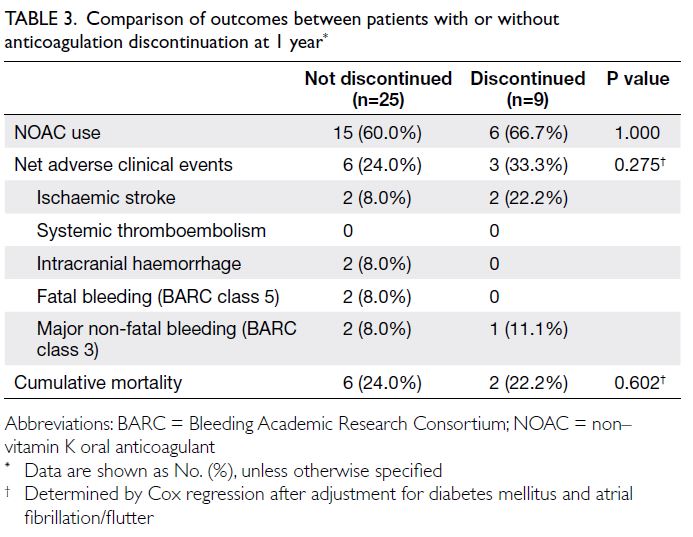

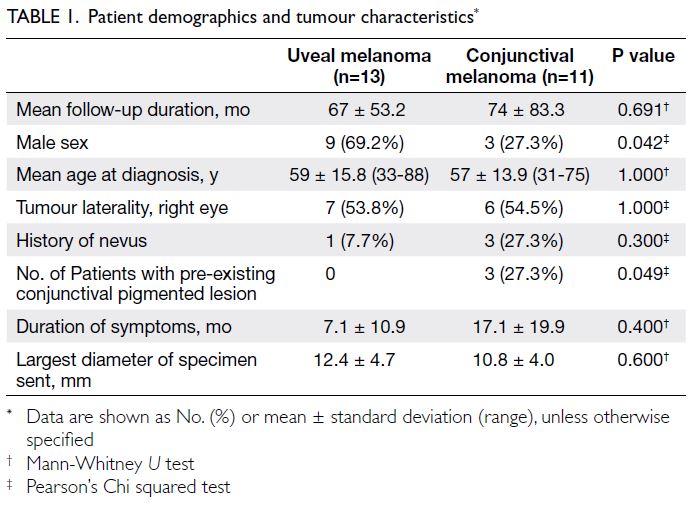

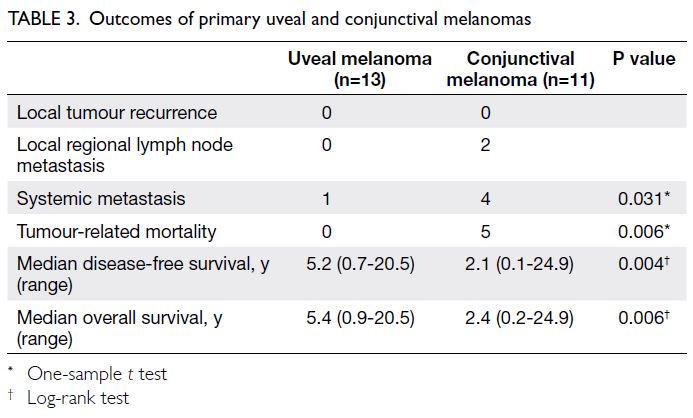

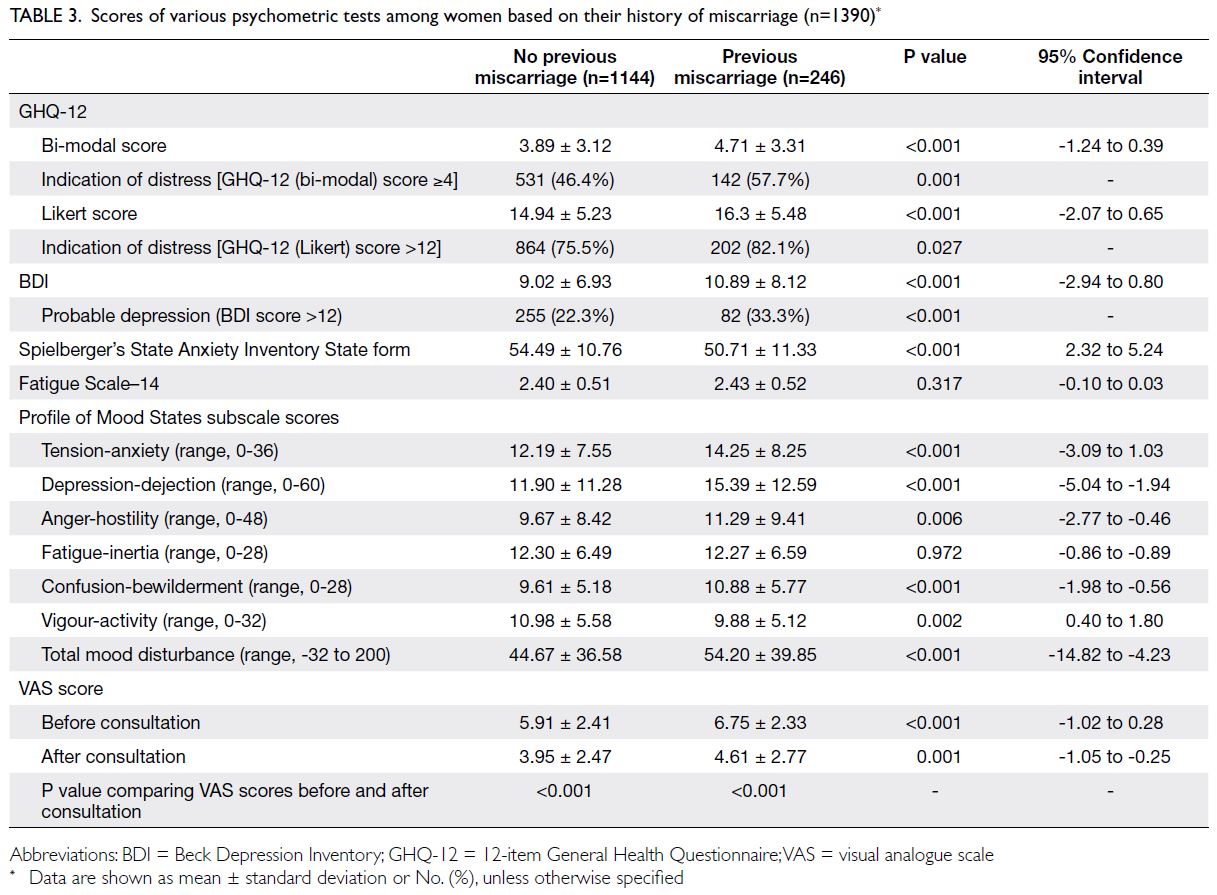

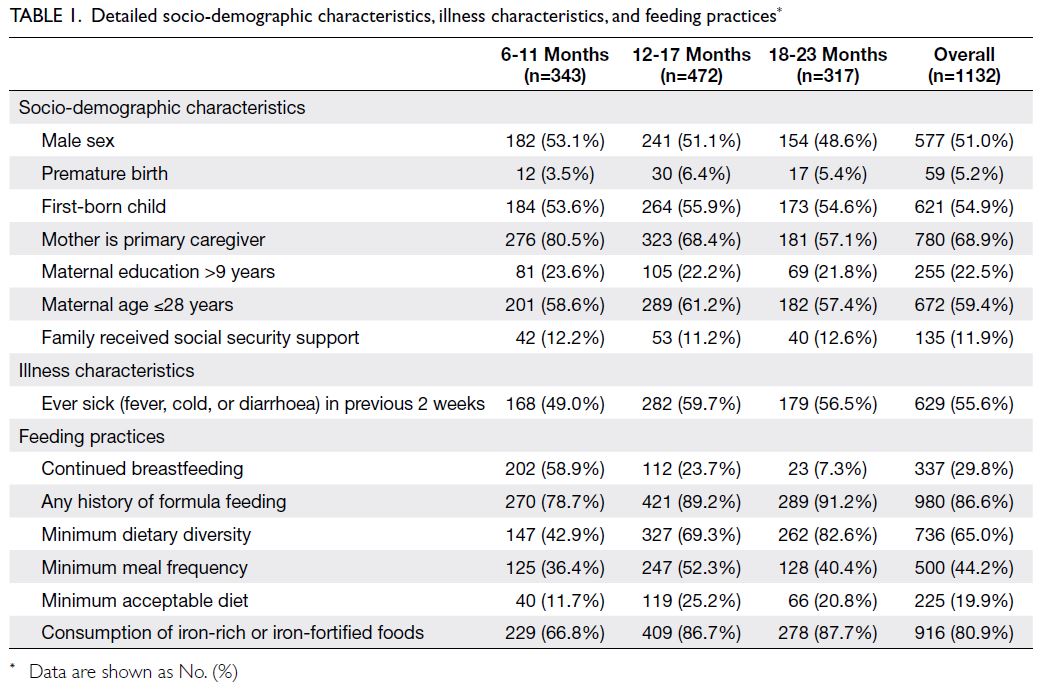

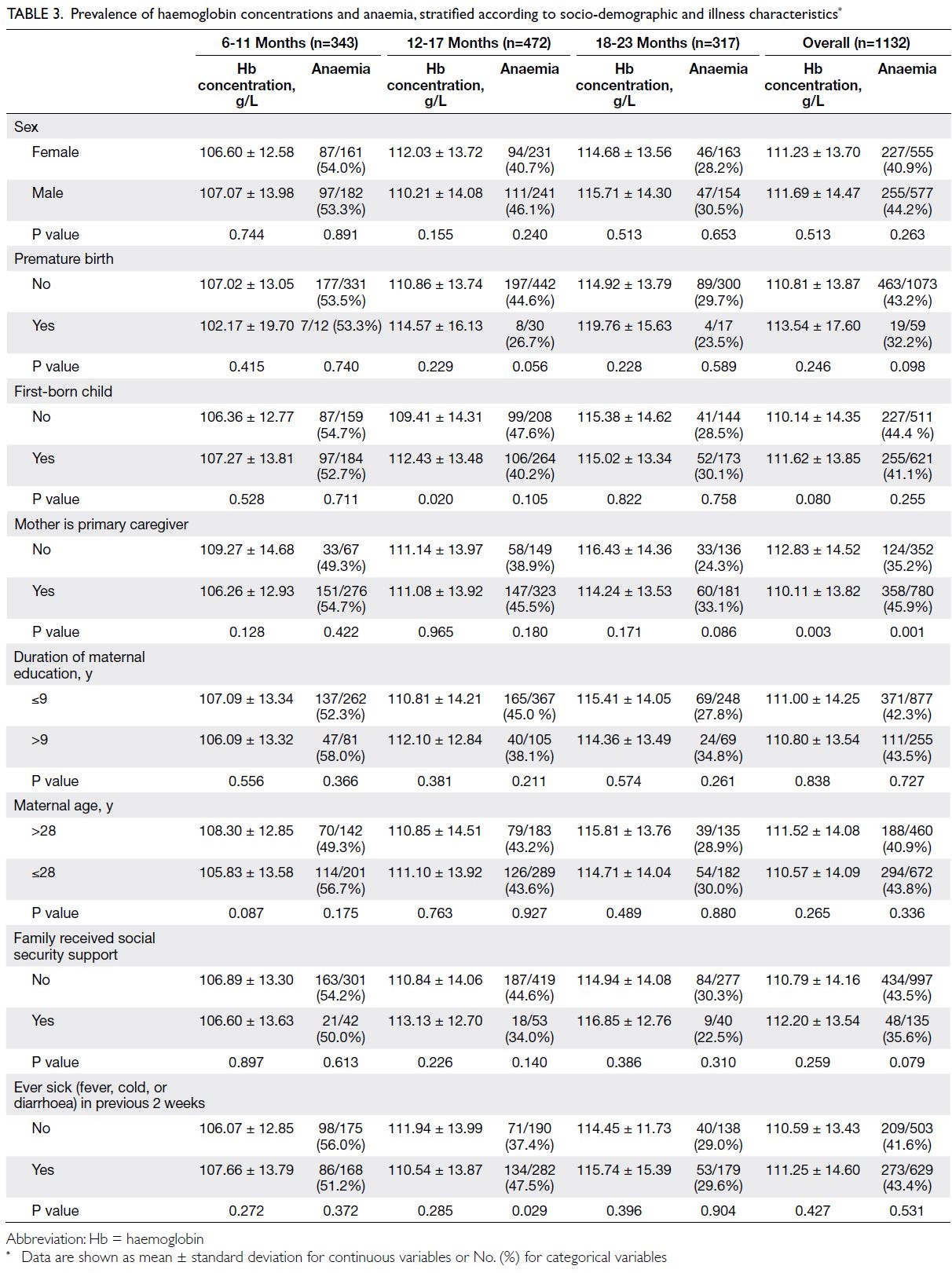

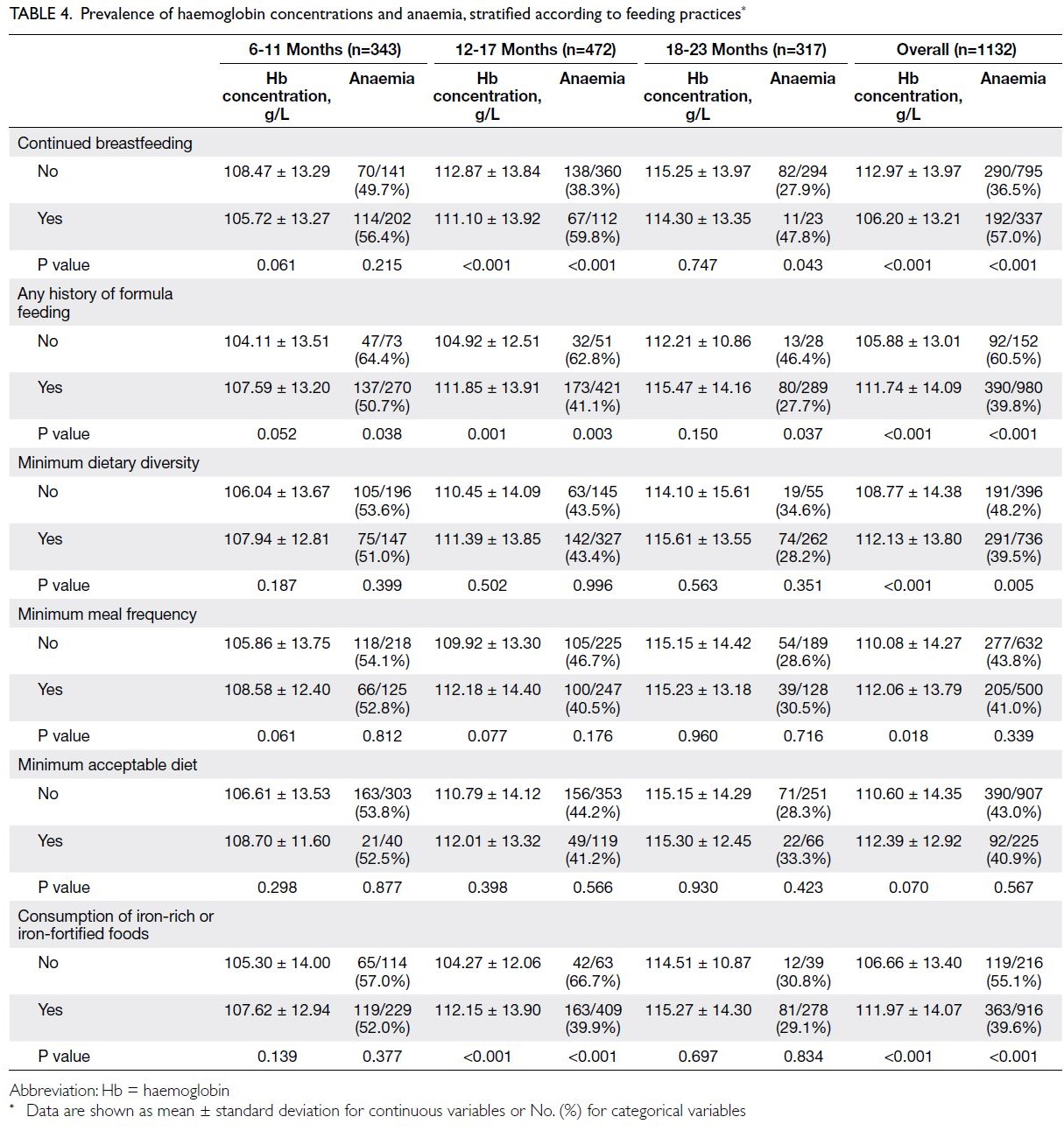

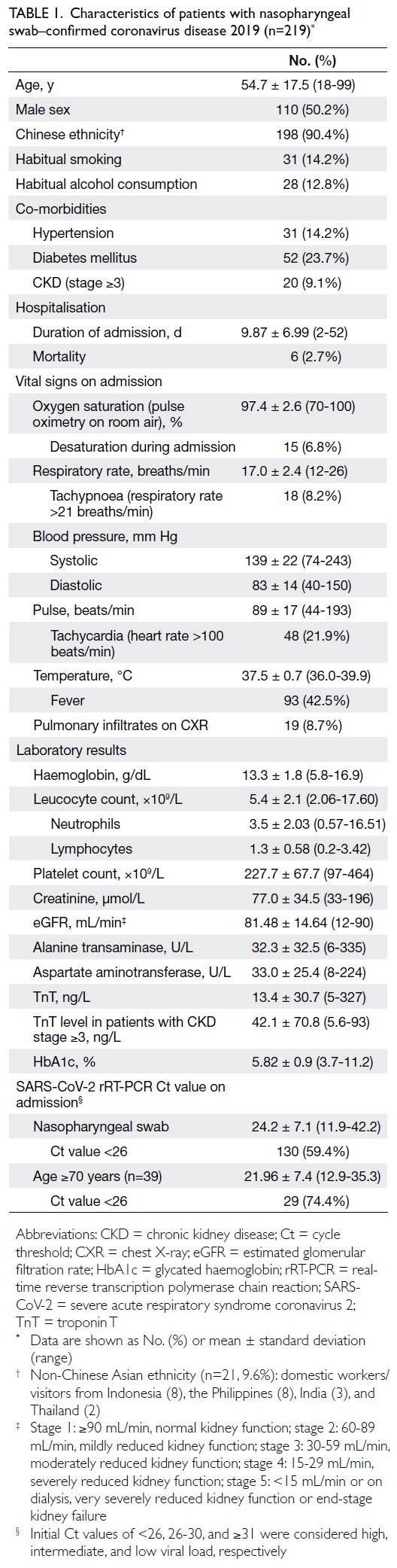

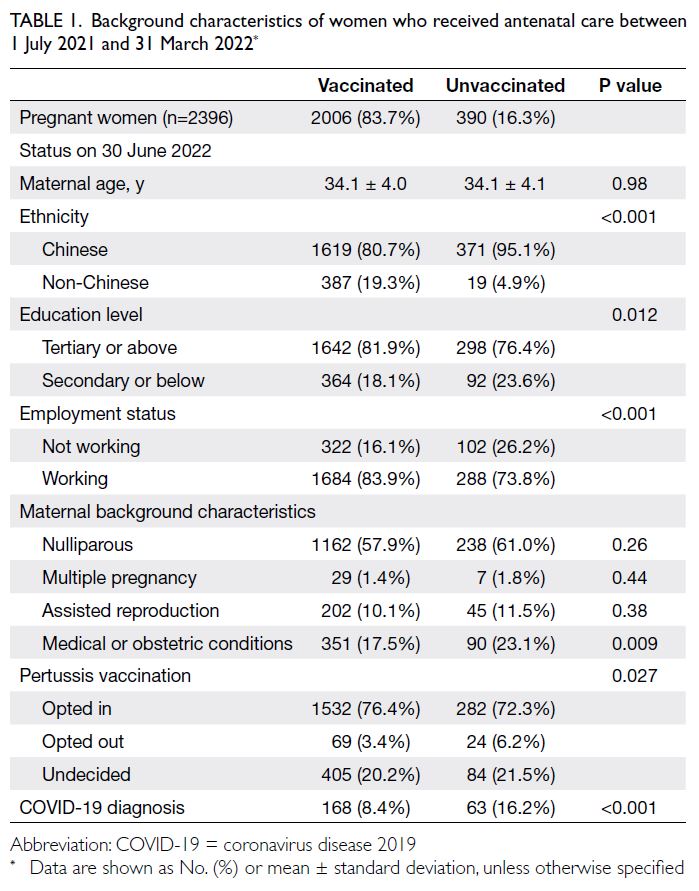

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of

2396 pregnant women who had attended the booking

antenatal visit between 1 July 2021 and 31 March 2022.

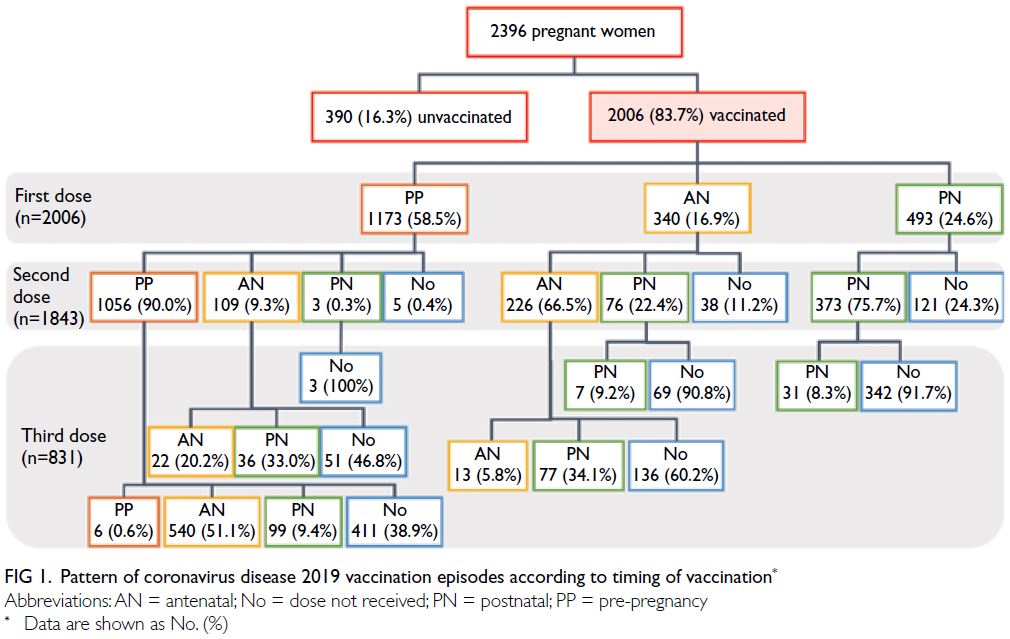

As of 30 June 2022, 2006 (83.7%), 1843 (76.9%), and

831 (34.7%) women had received the first, second,

and third doses of COVID-19 vaccine, respectively.

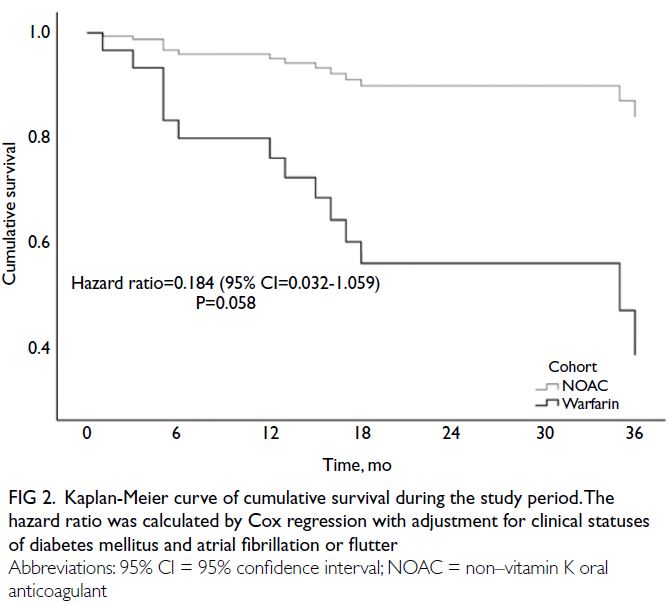

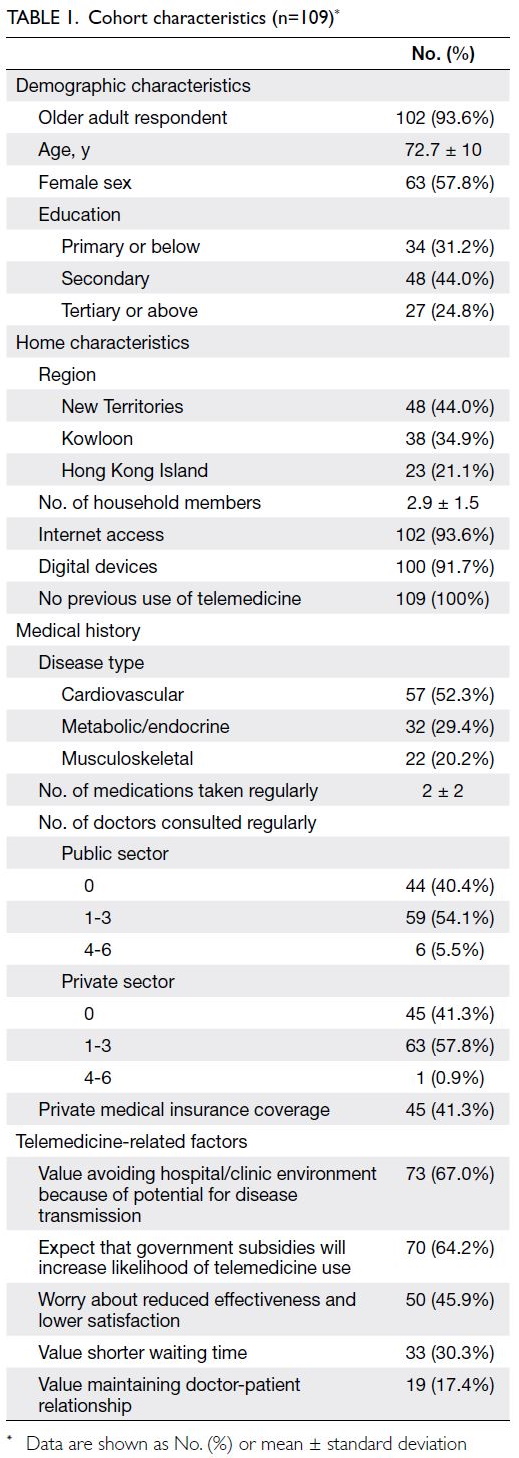

Among the 1843 women who had received two doses

of vaccine, 1056 (57.3%) underwent vaccination

before pregnancy (Fig 1). Of these 1843 women, 831

received a third dose; the median interval between

the second and third doses was 280 days (interquartile

range, 239-308). Of the remaining 1012 women who

had received only two doses of vaccine, 684 (67.6%)

and 504 (49.8%) had already passed the 90-day and 180-day intervals, respectively. Their median

number of days elapsed since the last vaccine was 315

(interquartile range, 145-368), which considerably

exceeded the recommended 90-day interval.

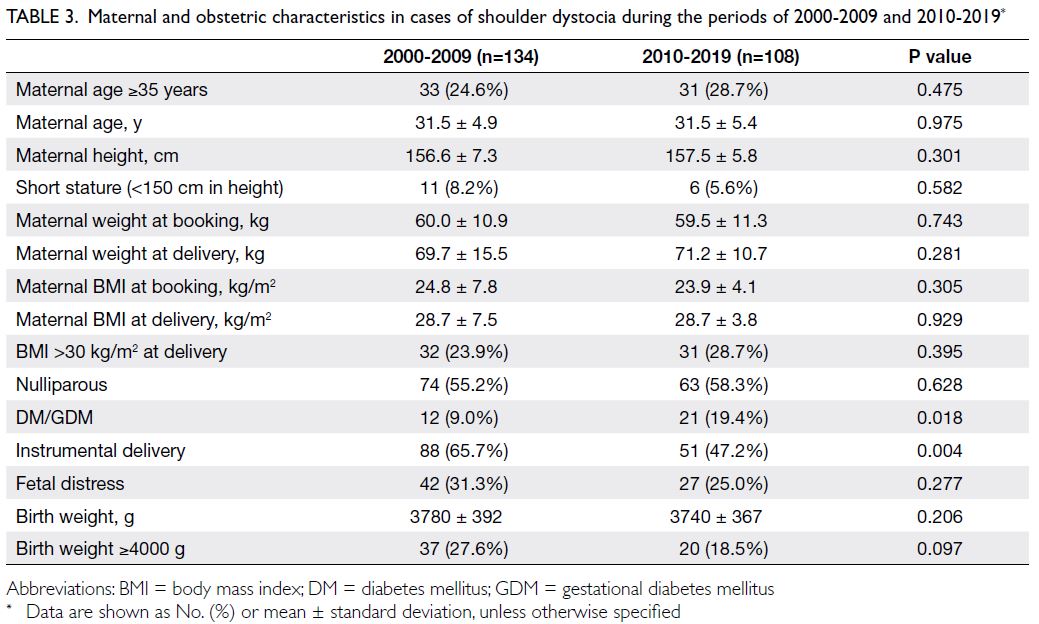

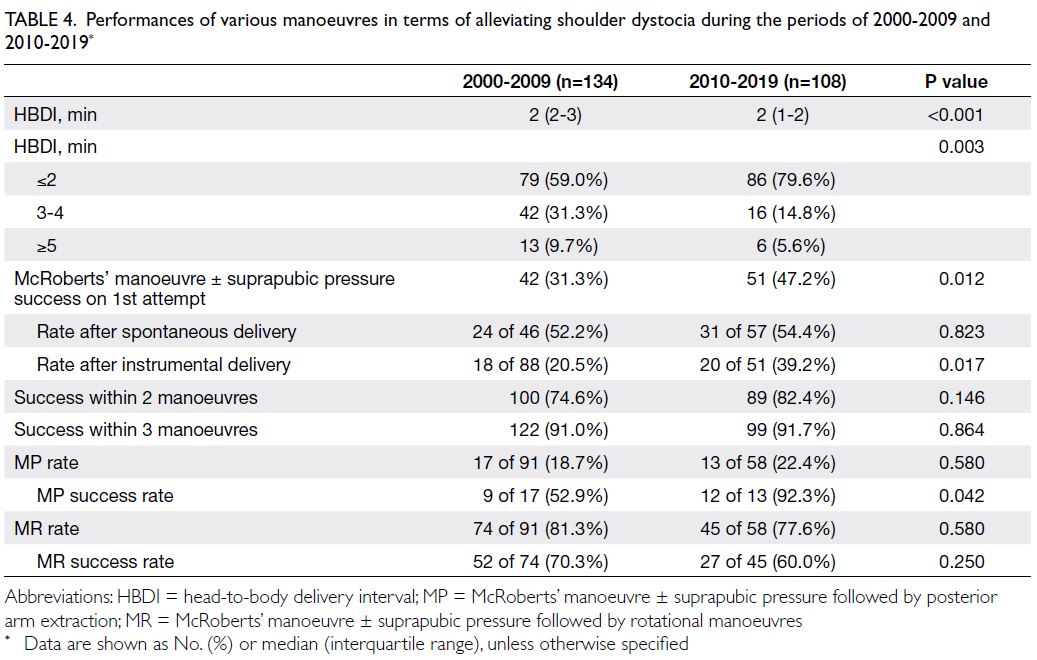

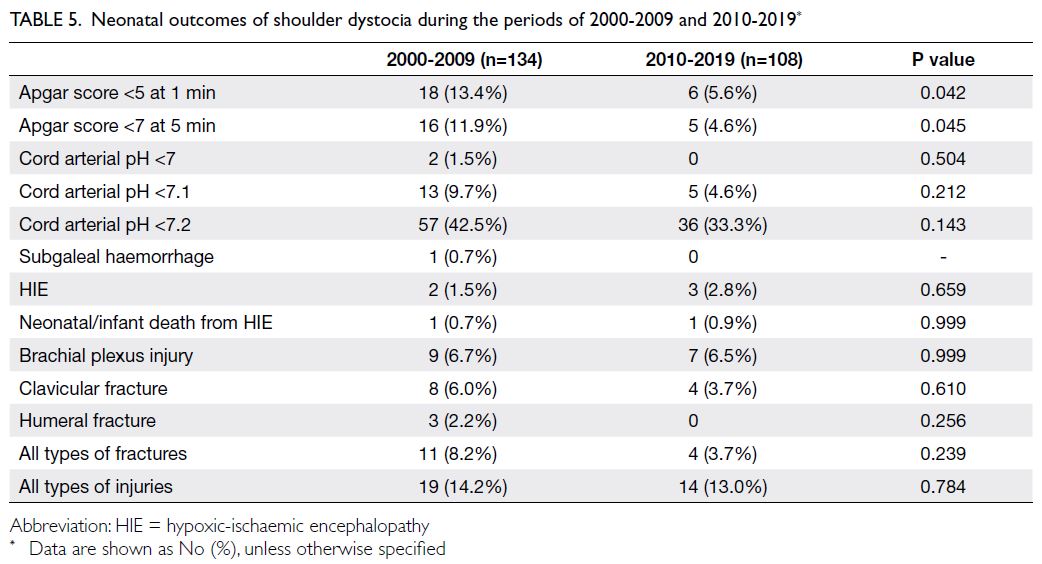

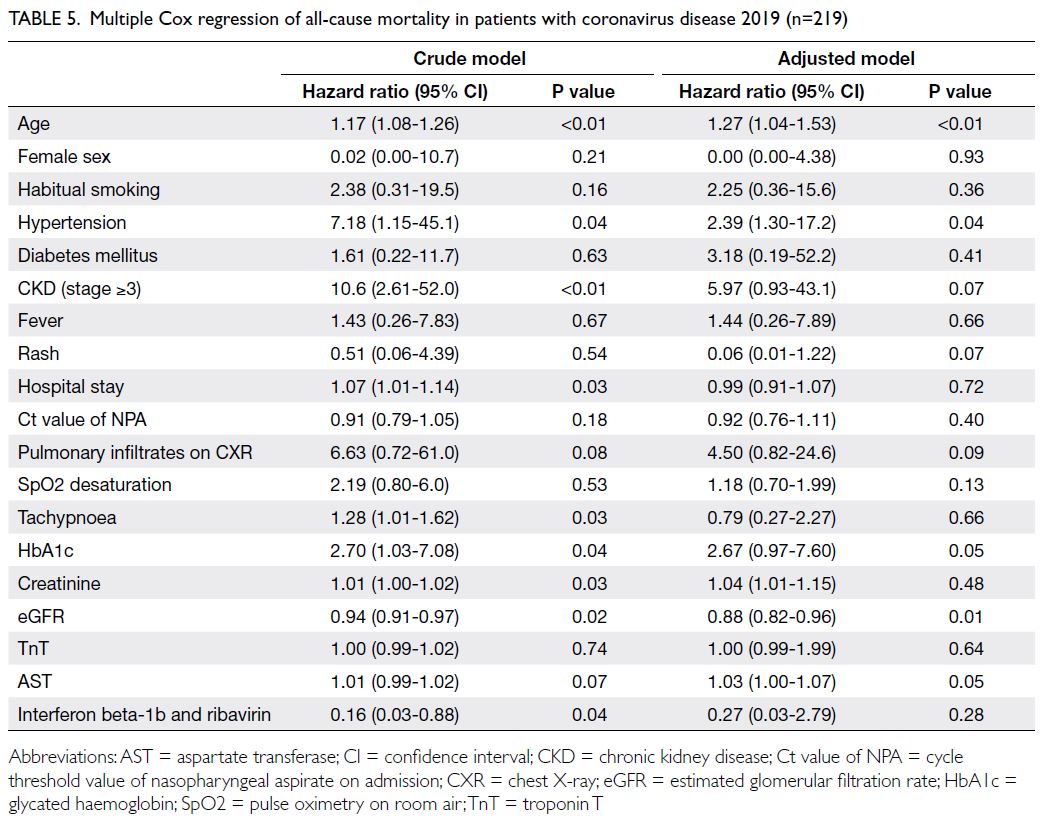

Table 1. Background characteristics of women who received antenatal care between 1 July 2021 and 31 March 2022

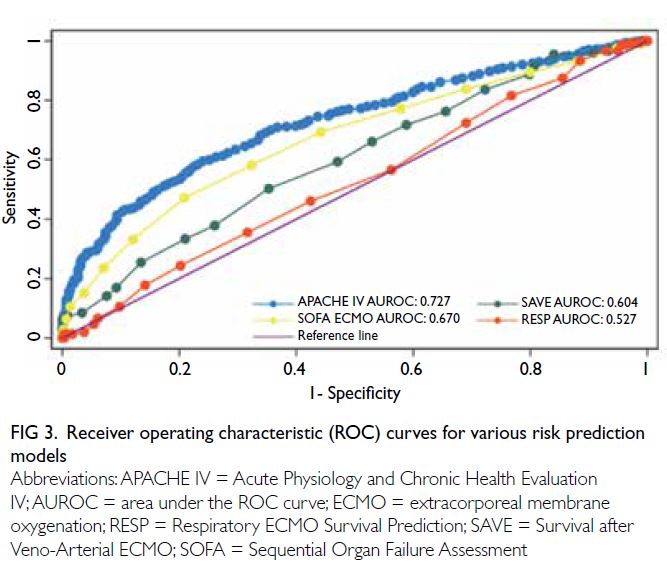

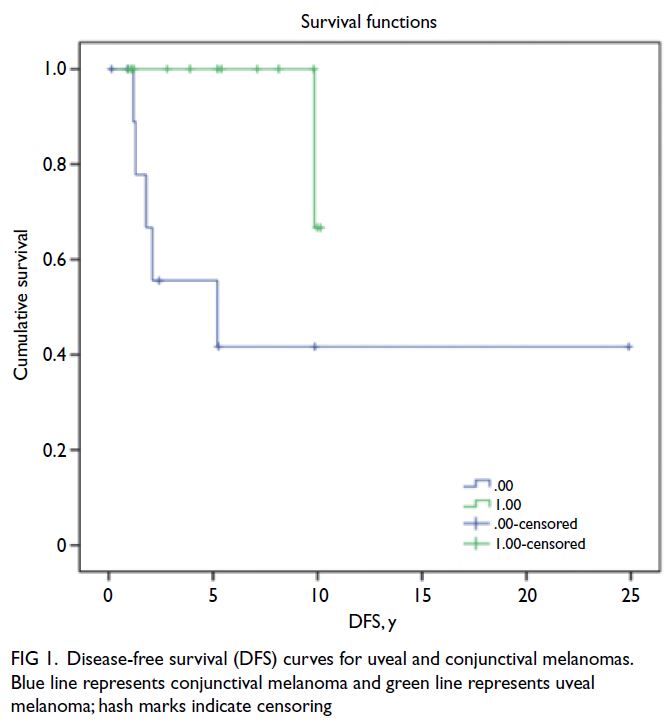

Figure 1. Pattern of coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination episodes according to timing of vaccination

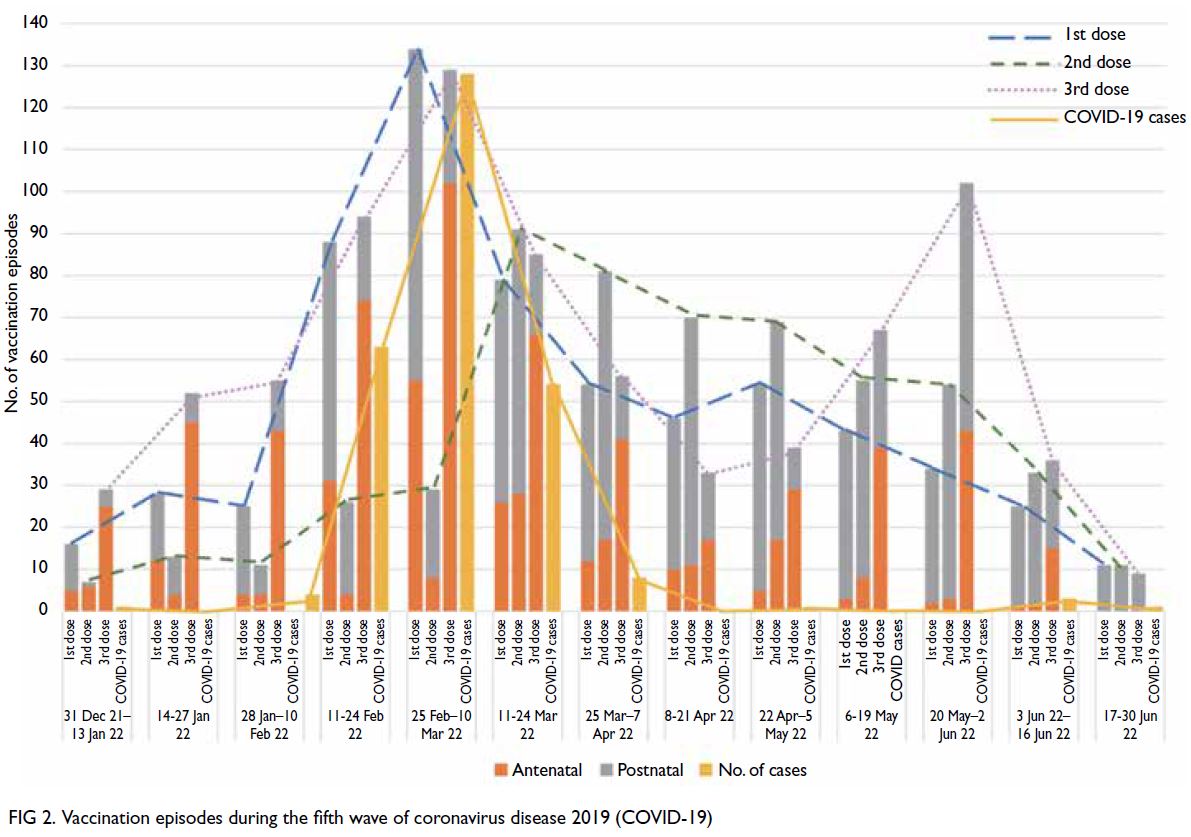

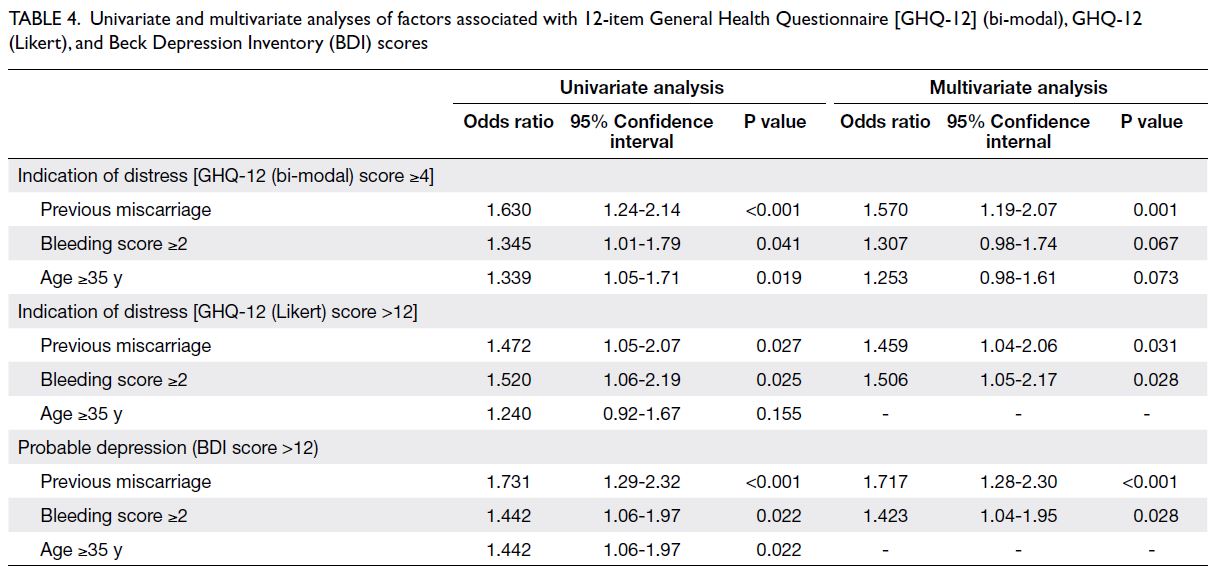

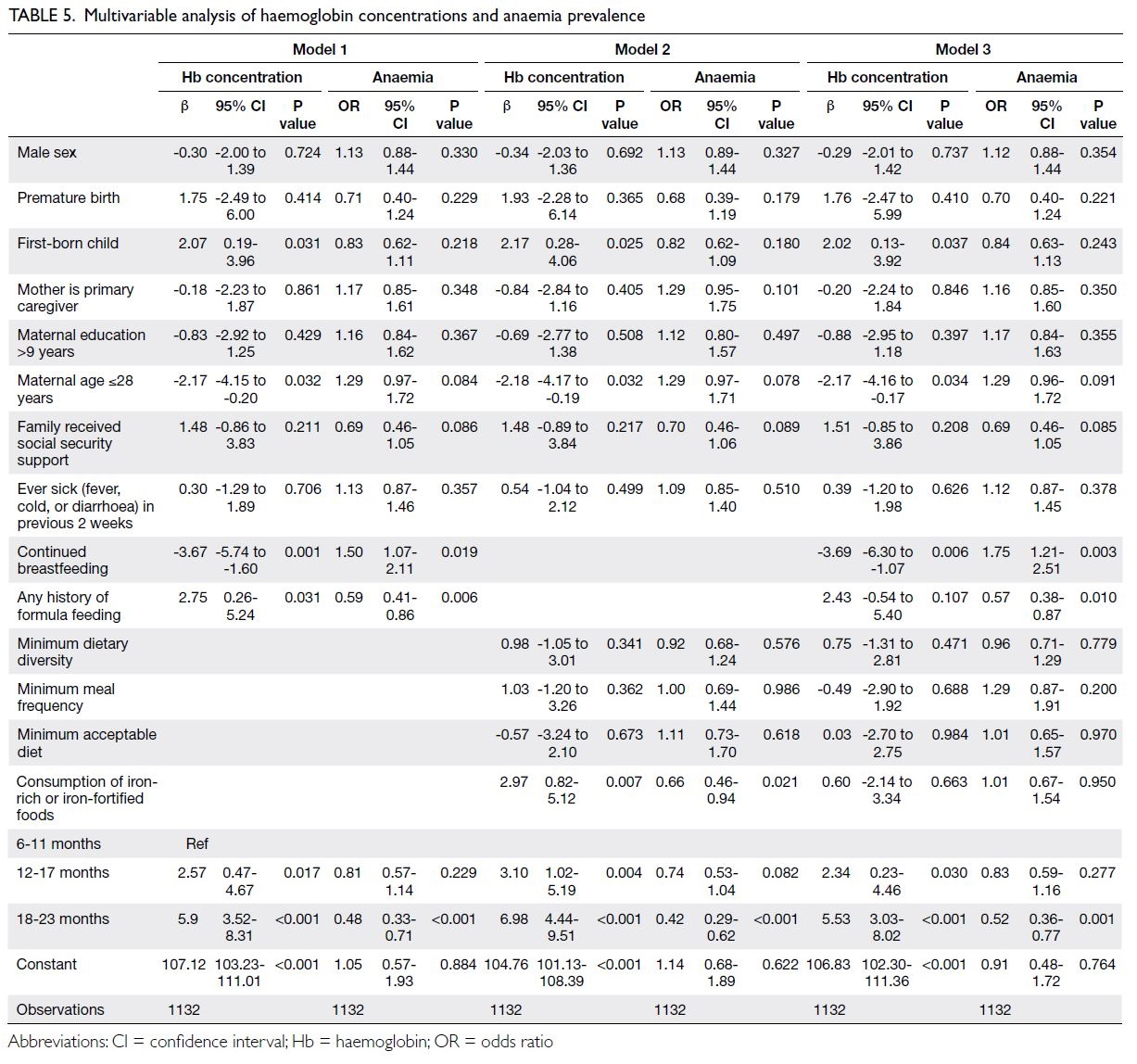

Only 26.6% (1243/4680) of vaccination episodes

occurred during pregnancy. Among women who

underwent antenatal vaccination, 65.7% (817/1243)

had it during the fifth wave of COVID-19 between

January 2022 and June 2022; 65.7% (537/817) of

these women received the third dose. The two peaks

of vaccination for third dose were observed in early

March 2022 and late May 2022 (Fig 2).

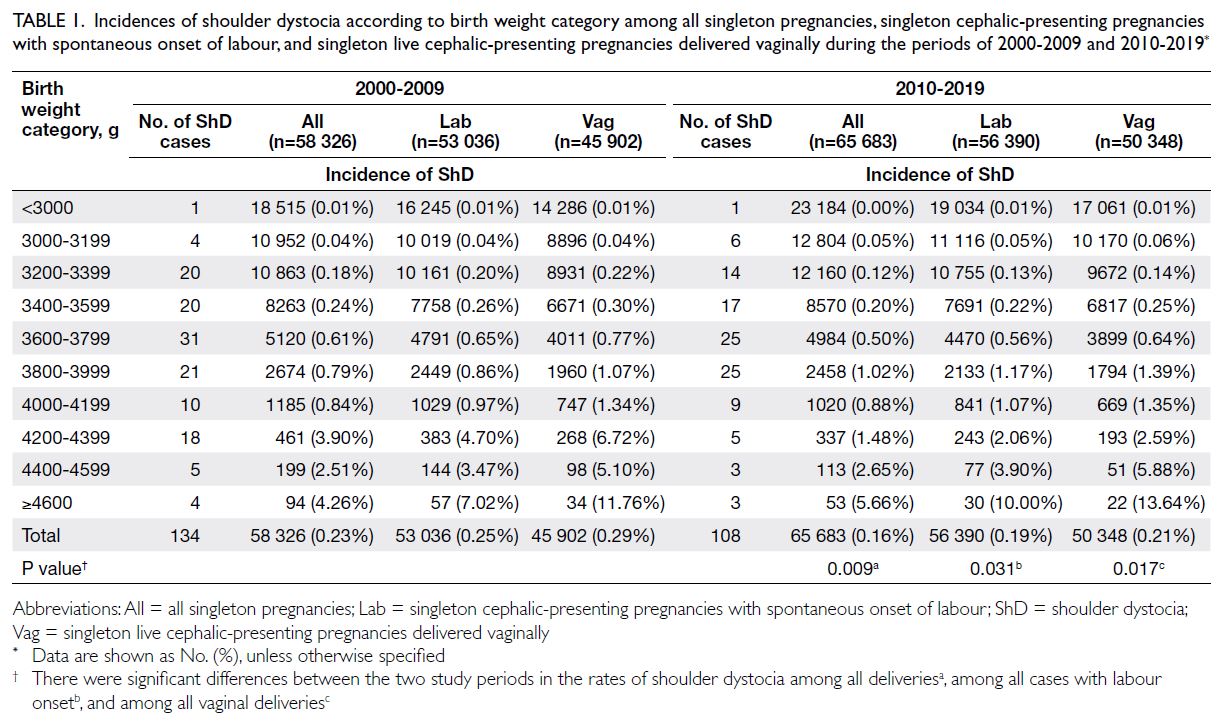

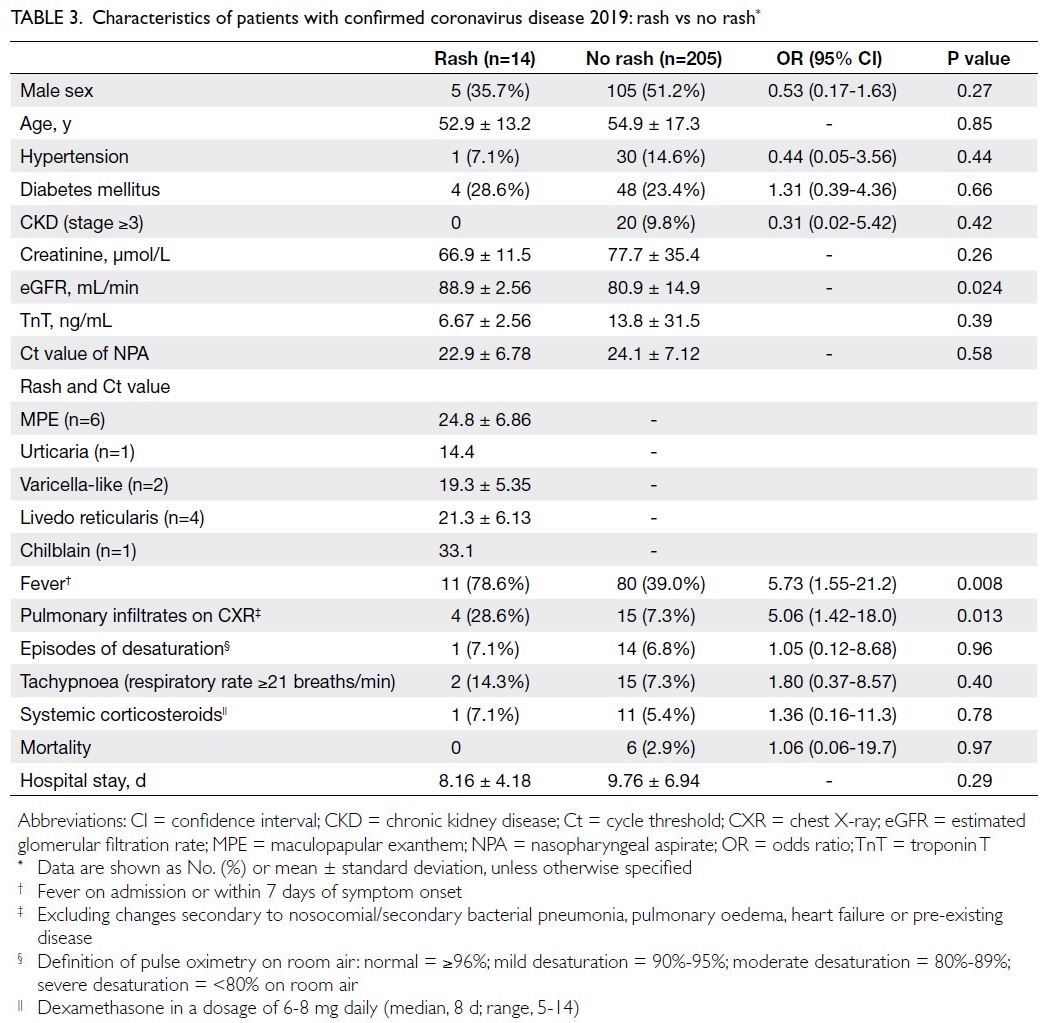

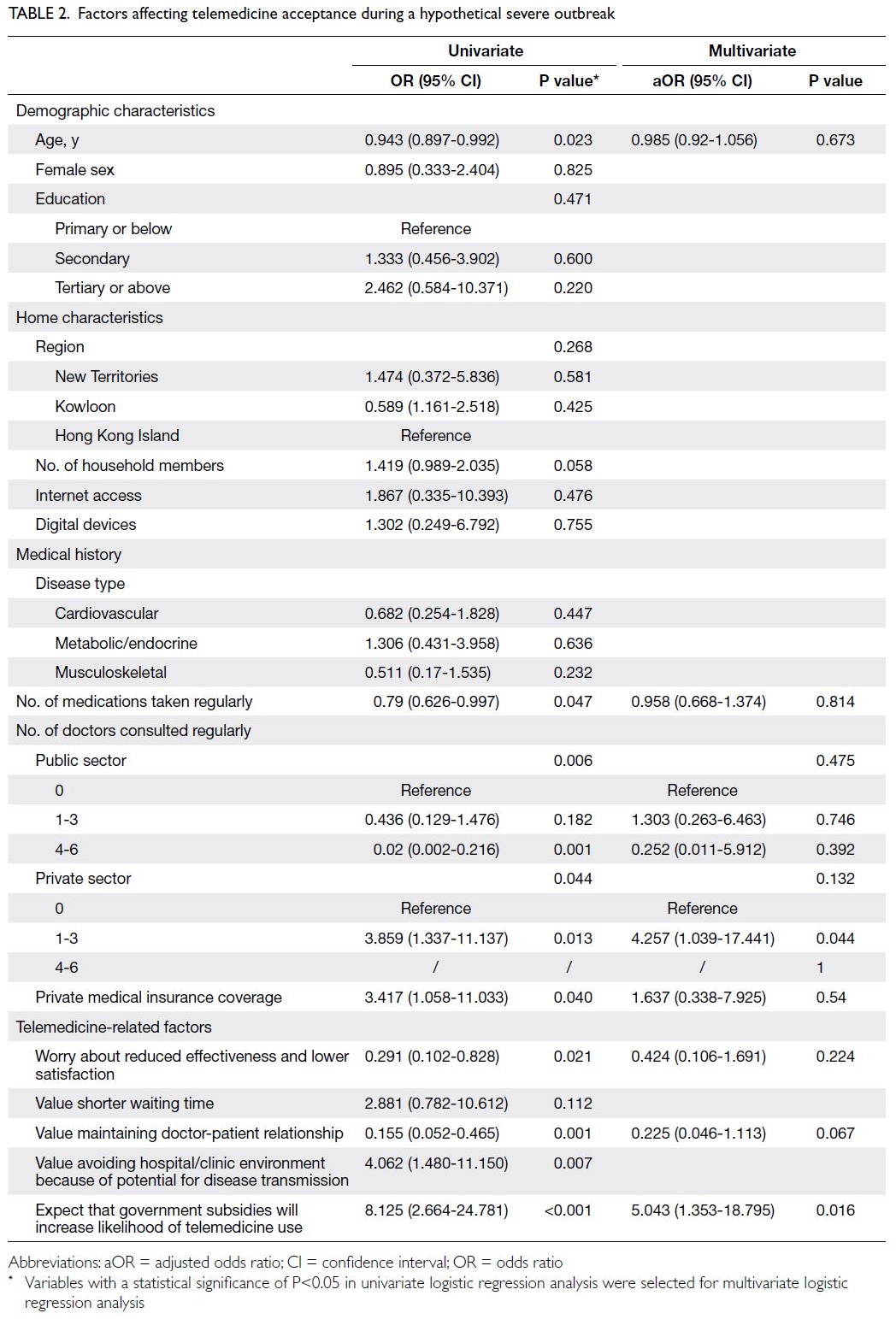

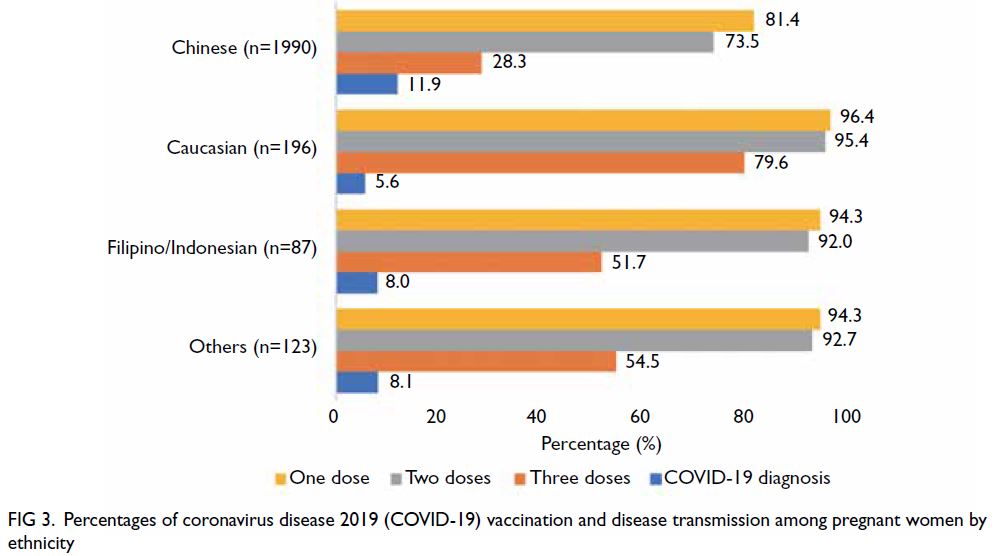

The vaccination rate was the lowest among

Chinese women (81.4%), but the highest among

Caucasian women (96.4%) [Fig 3]. Multivariate

analysis showed that active working status (odds

ratio [OR]=1.94; 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.47-2.56) was significantly associated with a higher

COVID-19 vaccination rate, whereas Chinese

ethnicity (OR=0.21; 95% CI=0.13-0.33) and

women with obstetric complications (OR=0.72;

95% CI=0.55-0.94) were significantly associated with

a lower COVID-19 vaccination rate.

Figure 3. Percentages of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination and disease transmission among pregnant women by ethnicity

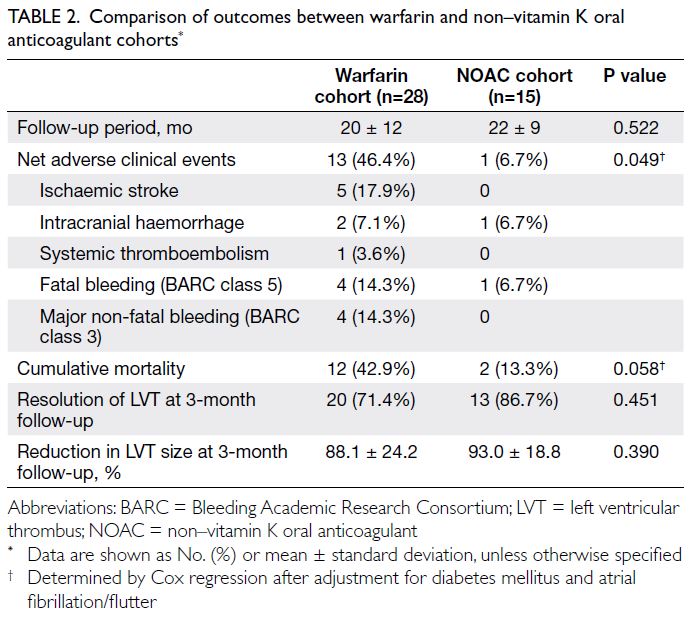

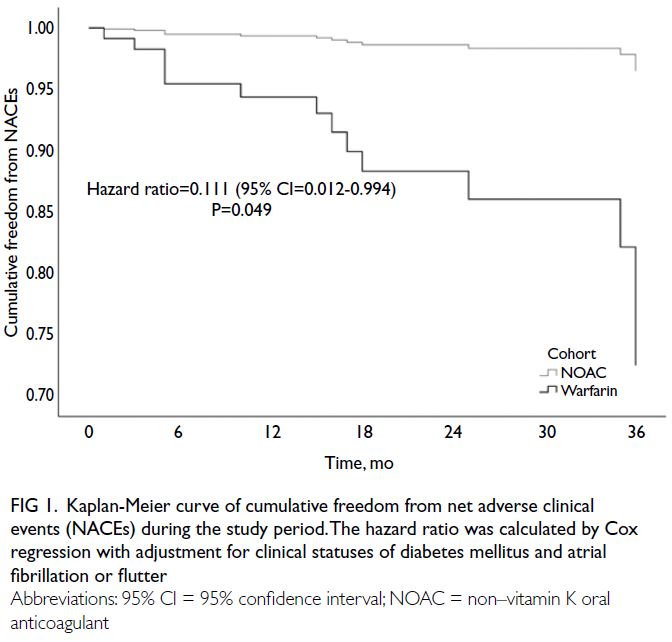

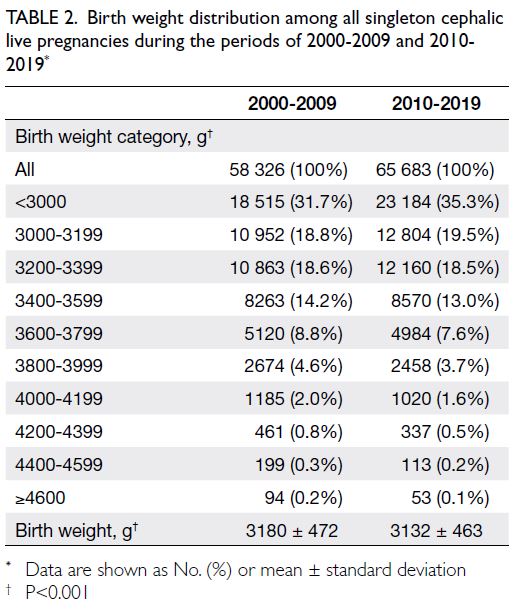

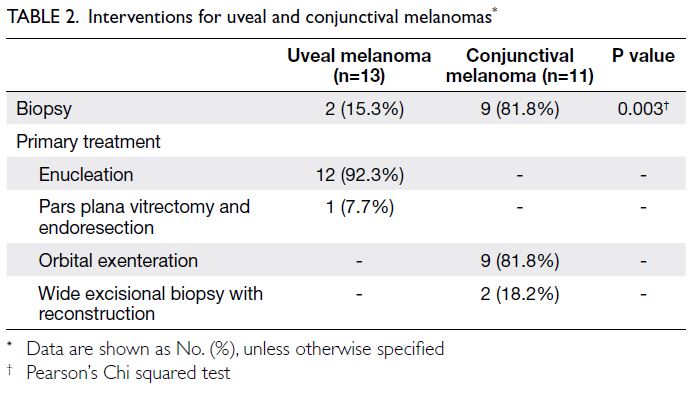

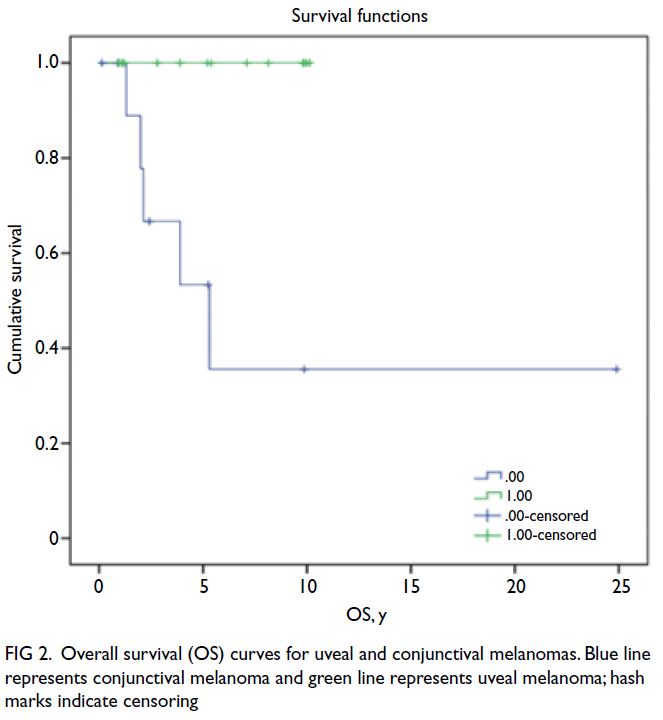

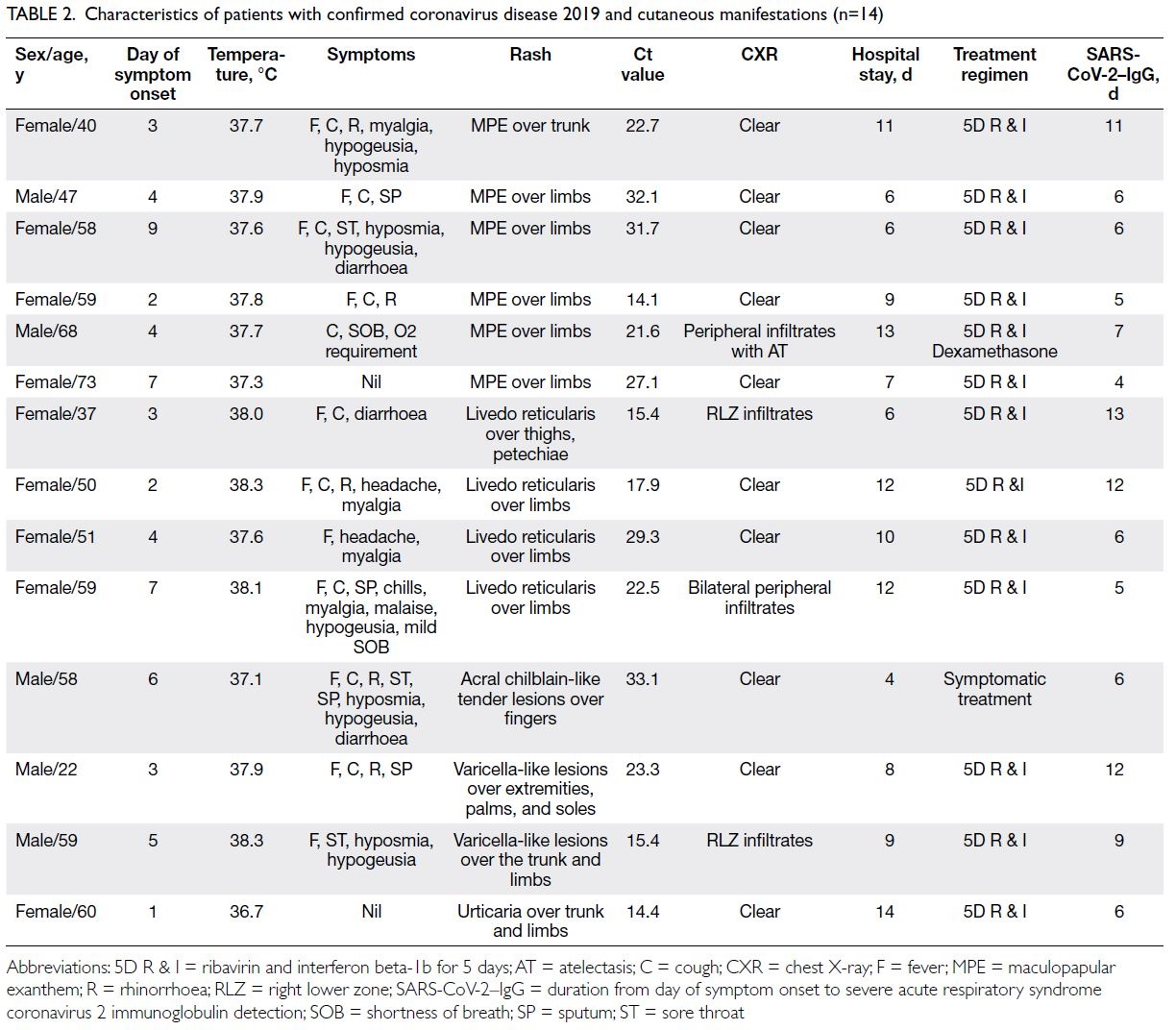

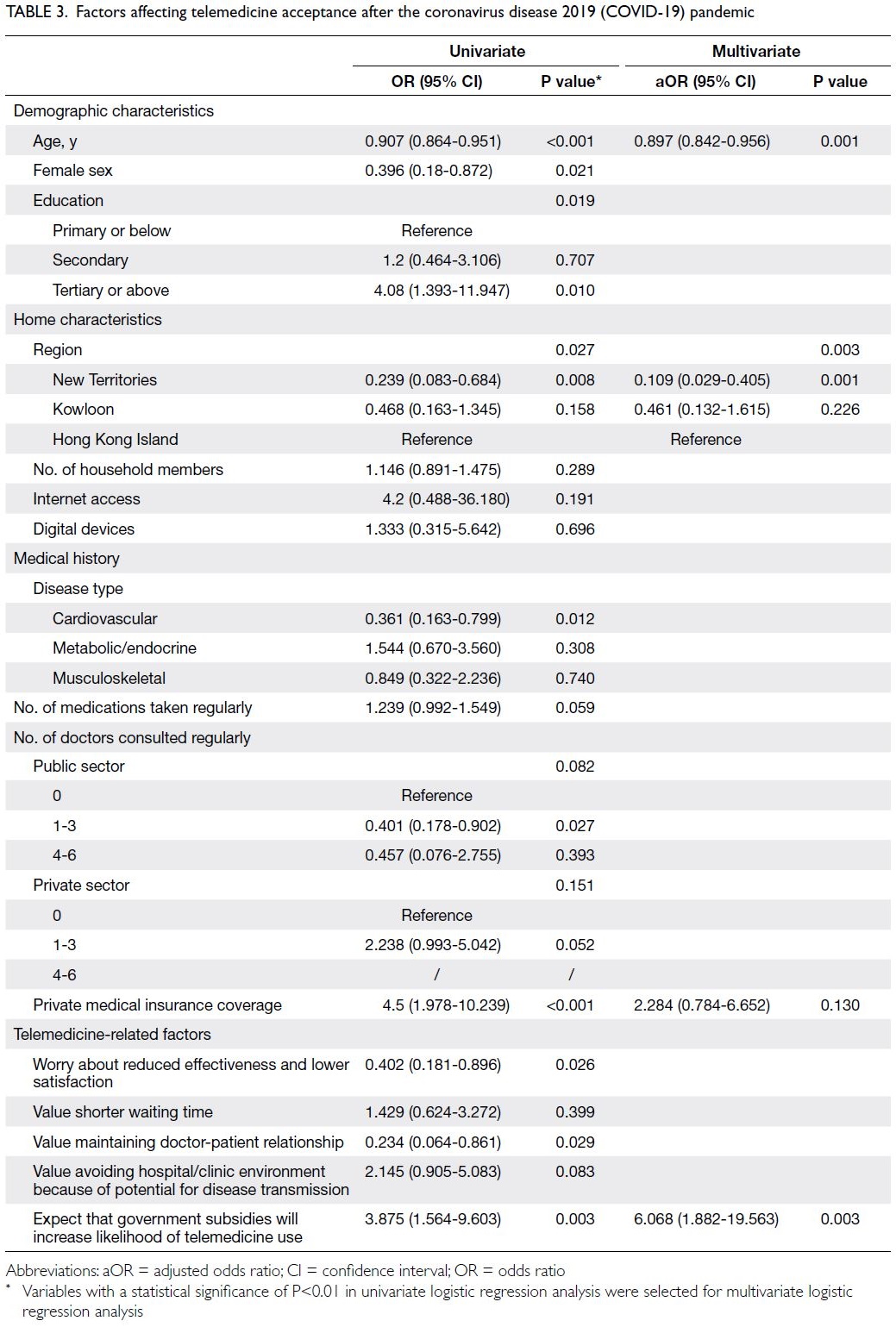

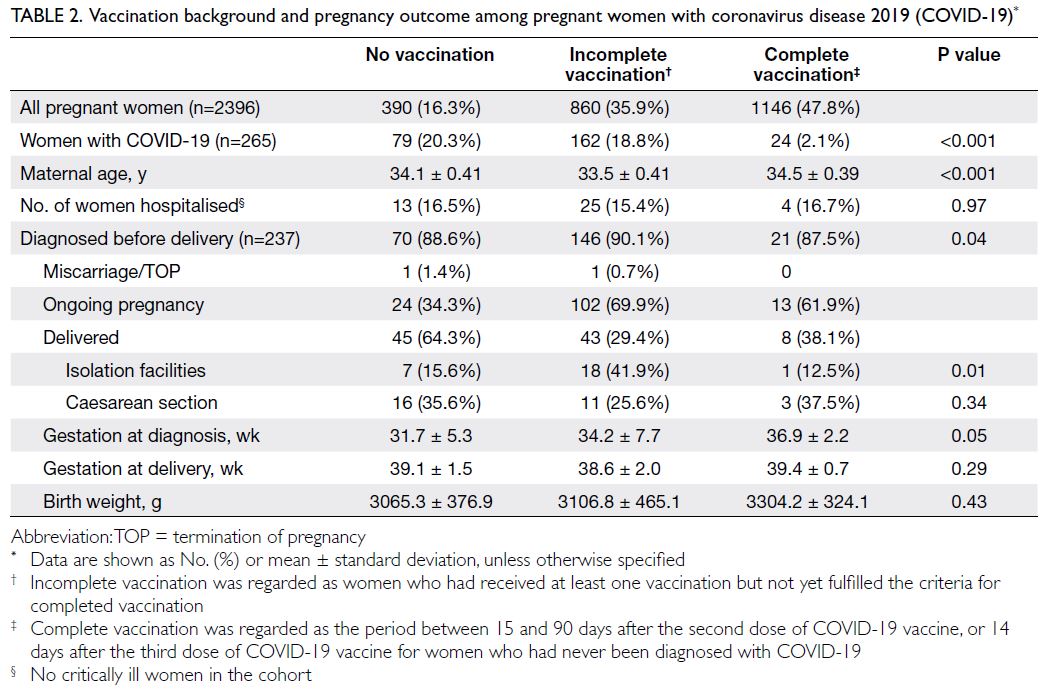

In total, there were 265 (11.1%) COVID-19

cases in this cohort; the earliest diagnosis was made

on 1 January 2022 during the fifth wave of COVID-19

in Hong Kong (Table 2). The disease rate was more

than tenfold higher in women who had no (20.3%)

or incomplete (18.8%) vaccination, compared

with women who had complete vaccination (2.1%;

P<0.001). After exclusion of pregnancies among

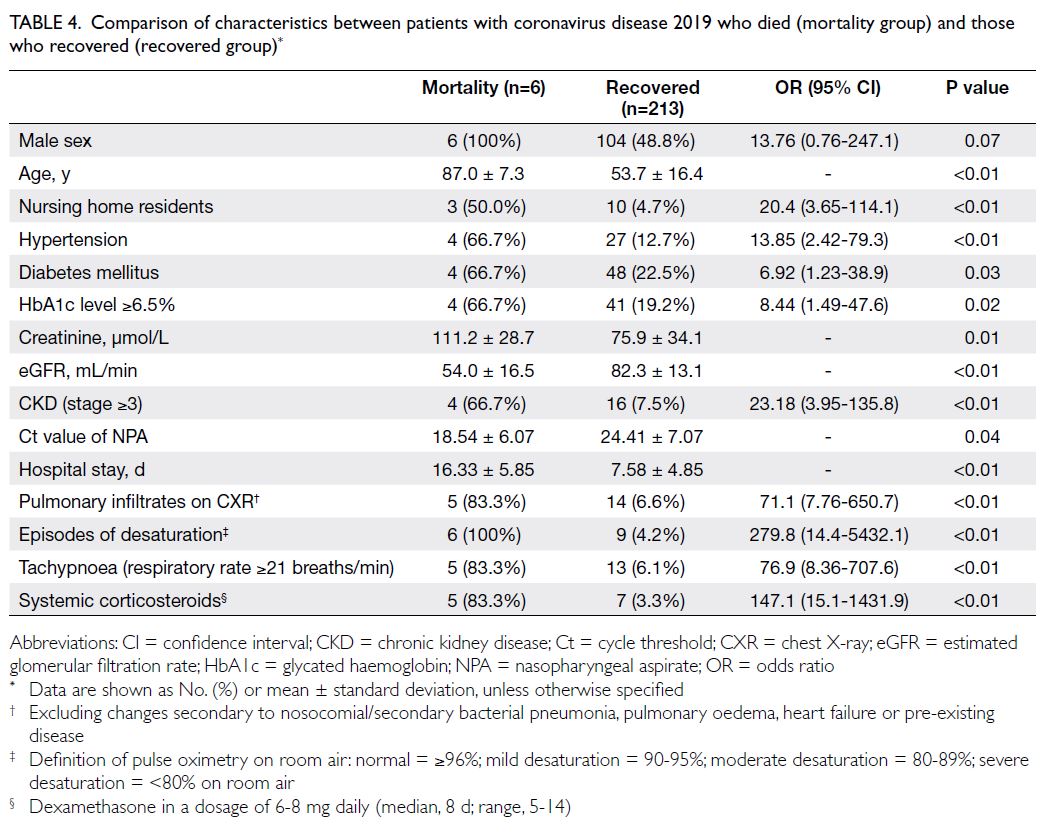

women aged ≤19 years, there was an insignificant

trend of lower vaccination among young women

(ie, aged 20-29 years), but their disease rate was the

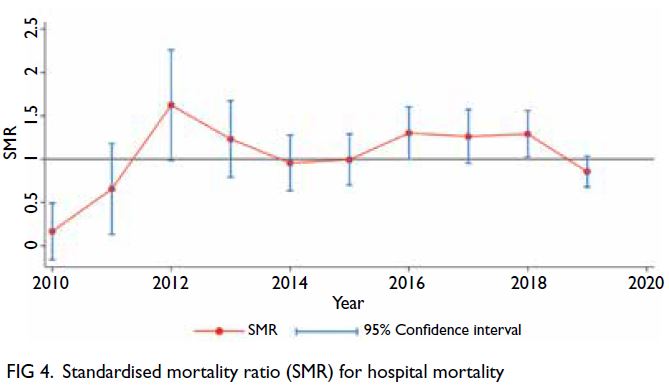

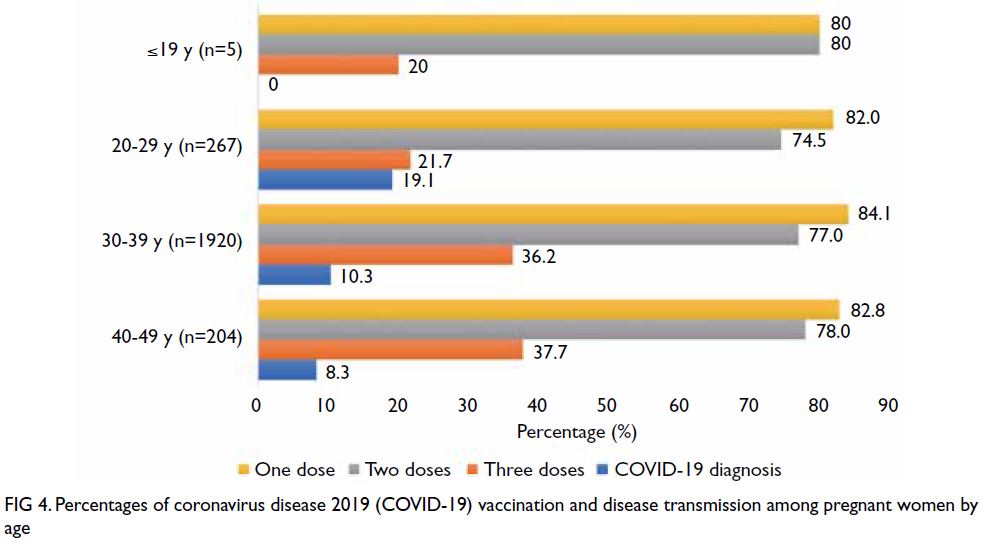

highest (19.1%) [Fig 4].

Table 2. Vaccination background and pregnancy outcome among pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

Figure 4. Percentages of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination and disease transmission among pregnant women by age

Among 237 (89.4%) women who had an

antenatal diagnosis of COVID-19, 42 (17.7%)

required admission for monitoring and 26 (11.0%)

delivered in an isolation facility. No women required

intensive care or oxygen support. There were no

adverse maternal outcomes or cases of vertical

transmission.

Discussion

Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination

To our knowledge, this is the first report of the low

COVID-19 vaccination rate (83.7%) among pregnant

women in Hong Kong. This rate is considerably lower

than the single-dose rate among the general public

(92.7%) that was reported on the government’s

vaccination dashboard on the final day of the study

period (ie, 30 June 2022).15 Furthermore, the disease

rate was more than threefold higher in women who had no or incomplete vaccination, compared with

women who had complete vaccination.

Pregnant women are considered a vulnerable

group. The substantial increase in the disease

rate, combined with a lower vaccination rate,

among women aged 20 to 29 years is particularly

concerning. A case of COVID-19 during pregnancy

can lead to adverse obstetric outcomes, including

increased risks of preterm delivery, growth

restriction, and stillbirth.16 In addition to the effectiveness of vaccination in terms of reducing

severe complications, the transplacental transfer

of immunoglobulins after maternal vaccination

might provide infants with protection against

COVID-19.10 16 17 18

Vaccine hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy is a potential public health

problem.19 The five psychological antecedents of

vaccination are confidence, complacency, constraints,

calculation, and collective responsibility.20 21

Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination has varied

among countries, with the highest rates reported

in India, the Philippines, and Latin America.22 In

the present study, Chinese women had a lower

vaccination rate, compared with their non-Chinese

counterparts.

The COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to

a decrease in vaccine hesitancy.23 In May 2021, a

systemic review showed that an estimated 47% of

pregnant women worldwide intended to undergo

COVID-19 vaccination.24

Communities generally become more

complacent when the number of disease cases is

low, suggesting that the perceived risk of disease

transmission is minimal. This phenomenon was

evident in Hong Kong across several waves of

COVID-19 transmission.15 The vaccination rate

increased during the fifth wave of COVID-19 when

there was an exponential surge in the number of

disease cases. A similar pattern was observed in the

present study, such that two-thirds of the antenatal

vaccination episodes occurred during the fifth wave

of COVID-19 in Hong Kong.

Despite this relative surge in vaccination,

around two-thirds of women eligible for the third

dose did not receive it during pregnancy. This delay

poses a major threat because the protective effect of the previous two doses may have dissipated.

Importantly, although the rate of vaccination was

higher in the antenatal group than the postnatal

group, most women in the antenatal group had

undergone vaccination before pregnancy. Thus, they

may have a higher risk of serious adverse effects

from COVID-19 if they become ill in the peripartum

period. After exclusion of the small number of

pregnant women aged ≤19 years, vaccination rates

were consistently low among pregnant women of

all ages. Pregnant women may have a higher risk of

disease transmission in future waves of COVID-19;

at the end of the present study, only one-third of

pregnant women in this cohort had received three

doses of vaccine.

Lack of confidence has been identified as

the main factor consistently associated with lower

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.3 The implementation

of the stringent vaccine pass policy had driven

another peak of vaccination in late May 2022.

However, nearly half of the women who had received

two doses of vaccine were indeed overdue for the

third dose, and hence did not fulfil the vaccine

pass for entrance to specific premises or could not

attend obstetric clinics without undergoing nucleic

acid testing. This group of vaccine had received

COVID-19 vaccine before but had it mostly before

pregnancy. Pregnancy could represent the key

hindrance for their vaccination in the antenatal

period. Government policy might not be adequate

enough for promoting vaccination in pregnant

women. Concern about possible harmful side-effects

was the top reason for reluctance; confidence in

COVID-19 vaccine safety and efficacy was the main

predictor of acceptance, particularly in the pregnant

population.8 22 In a Japanese cohort, concerns about

potential effects on the fetus and breastfeeding were

the main reasons for low COVID-19 vaccination

acceptance.25 These findings highlight the need to

distribute correct information and provide sufficient

education to address concerns among women of

reproductive age. In particular, antenatal women

should receive additional information concerning

vaccine safety during pregnancy.

Vaccination promotion

A study in Hong Kong showed that recommendations

from the government constituted the strongest

factor driving COVID-19 vaccine acceptance.2

Education about the safety and benefit of vaccination

is also important.7 Webinars would be useful in

efforts to educate the general public. Within the

hospital setting, vaccination teams comprising

obstetricians and midwives could allay concerns

and dispel myths about vaccination among working

staff at all levels; this approach could provide useful

information for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

There is also a need to combat physician hesitancy in recommending COVID-19 vaccination for pregnant

women.26 To address this need, the HKCOG revised

its recommendations on 3 March 2022 to indicate

that women who are planning to become pregnant,

are pregnant, or are breastfeeding should undergo

COVID-19 vaccination along with the general

population.12 A corresponding educational video to

promote COVID-19 vaccination was made available

on 5 March 2022.12

Possible interventions to promote vaccination

in Hong Kong include the provision of vaccines at

convenient venues and the involvement of healthcare

professionals in information dissemination.27 During

the fifth wave of COVID-19, pregnant women

were proactively asked to consider COVID-19

vaccination when they attended obstetric clinics.

Leaflets were distributed with information about the

HKCOG recommendations, as well as community

vaccination sites. The establishment of a pathway

specifically for pregnant women, which reduced

their waiting time in vaccine clinics, also helped to

increase the vaccination rate. Moreover, vaccination

was provided to women in the maternity wards of

some hospitals and women attending antenatal

clinics in Maternal and Child Health Centres. All of

these measures helped reduce vaccine hesitancy in

pregnant women.28

In Hong Kong, a pertussis vaccination

programme for pregnant women was launched on

2 July 2020.29 The programme was incorporated

into antenatal care, such that all pregnant women

received counselling concerning the rationale for

vaccination; the vaccine was administered during

obstetric follow-up. To facilitate vaccine availability

in our hospital, all women were asked to indicate

their preference concerning pertussis vaccination

during the first antenatal visit. It may be useful

to incorporate COVID-19 vaccination into the

maternal immunisation programme.

Strengths

This study had some notable strengths. The results

of the present large cohort study provide clinicians

and policymakers with key insights concerning the

COVID-19 vaccination rate among pregnant women

in Hong Kong. The study period was designed to

include both antenatal and postnatal periods for

a better understanding of vaccination behaviour

among women in each period. A real-time collection

method was adopted to capture COVID-19

vaccination records from the Clinical Management

System, thereby ensuring data reliability.

Limitations

Nevertheless, this study had some limitations. A small number of women who underwent COVID-19

vaccination outside Hong Kong were not automatically identified in the system; however, they were included

in the cohort if their vaccination history had been

documented in antenatal records. Because rapid

antigen self-tests were acceptable for diagnosis in

Hong Kong beginning on 26 February 2022, the

number of recorded COVID-19 cases in our cohort

might have been lower than the actual number of

cases if patients did not report positive COVID-19

test results to our department. Finally, this study did

not explore whether the generally more cautious

approach of pregnant women, in terms of avoiding

all types of diseases, might contribute to a lower

disease rate compared with the general public.

Conclusion

The rate of COVID-19 vaccination was low among

pregnant and postnatal women in Hong Kong in

early 2022. Pregnant women had a high risk of

disease transmission because many of them had not

received the third dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Urgent

measures are needed to promote vaccination among

pregnant women before future waves of COVID-19.

In particular, women should receive information

concerning vaccine safety to avoid unnecessary

delays related to pregnancy.

Author contributions

Concept or design: PW Hui, DTY Chan.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PW Hui.

Drafting of the manuscript: PW Hui, LM Yeung, JKY Ko, THT Lai, MTY Seto.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PW Hui.

Drafting of the manuscript: PW Hui, LM Yeung, JKY Ko, THT Lai, MTY Seto.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr TW Chay, Dr YF Chiu, Ms WK Choi, Dr TY Hui, Dr KH Lam, Dr KS Lee, Dr YH Luk, Dr SK Ma,

Dr HS Wang, Dr CCY Wong, Dr CL Wong, Dr LC Wong, and Dr CWK Yan of Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Mary Hospital for their contributions to research data retrieval and entry.

Declaration

The abstract has been presented online in the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists World Congress 2023 (14 June 2013, London, United Kingdom).

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review

Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority

Hong Kong West Cluster (Ref No.: UW 22-205). Informed

patient consent has been waived by the Board due to the

retrospective nature of the research.

References

1. MacDonald NE; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015;33:4161-4. Crossref

2. Wong MC, Wong EL, Huang J, et al. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: a population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine 2021;39:1148-56. Crossref

3. Xiao J, Cheung JK, Wu P, Ni MY, Cowling BJ, Liao Q. Temporal changes in factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake among adults in Hong Kong: serial cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2022;23:100441. Crossref

4. Beigi RH, Krubiner C, Jamieson DJ, et al. The need for inclusion of pregnant women in COVID-19 vaccine trials. Vaccine 2021;39:868-70. Crossref

5. Scientific Committee on Emerging and Zoonotic Disease

and Scientific Committee on Vaccine Preventable

Diseases, Centre for Health Protection, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Consensus interim recommendations on

the use of COVID-19 vaccines in Hong Kong (as of Jan 7,

2021). Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/consensus_interim_recommendations_on_the_use_of_covid19_vaccines_inhk.pdf . Accessed 30 Mar 2022.

6. Tao L, Wang R, Han N, et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19

vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in

China: a multi-center cross-sectional study based on health

belief model. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021;17:2378-88. Crossref

7. Sznajder KK, Kjerulff KH, Wang M, Hwang W, Ramirez SI,

Gandhi CK. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and associated

factors among pregnant women in Pennsylvania 2020. Prev

Med Rep 2022;26:101713. Crossref

8. Sutton D, D’Alton M, Zhang Y, et al. COVID-19 vaccine

acceptance among pregnant, breastfeeding, and

nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Am J Obstet

Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100403. Crossref

9. Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers TR, et al. Preliminary

findings of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine safety in pregnant

persons. N Engl J Med 2021;384:2273-82. Crossref

10. Halasa NB, Olson SM, Staat MA, et al. Effectiveness of

maternal vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 vaccine

during pregnancy against COVID-19–associated

hospitalization in infants aged <6 months—17 states, July

2021–January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep

2022;71:264-70. Crossref

11. Girardi G, Bremer AA. Scientific evidence supporting coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine efficacy and safety in people planning to conceive or who are pregnant or lactating. Obstet Gynecol 2022;139:3-8. Crossref

12. The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists. The Hong Kong College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists advice on COVID-19

vaccination in pregnant and lactating women (interim;

updated on 3rd March 2022). 2022. Available from:

http://www.hkcog.org.hk/hkcog/Upload/EditorImage/20220304/20220304134806_9035.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar 2022.

13. Hong Kong SAR Government. FEHD reminds catering

premises operators and customers to observe requirements

on third stage of Vaccine Pass. 2022. Available from:

https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202205/30/P2022053000726.htm?fontSize=1. Accessed 30 May 2022.

14. Hong Kong SAR Government. Government to implement

Vaccine Pass arrangement in designated healthcare

premises. 2022. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202205/21/P2022052100421.htm. Accessed 21 May 2022.

15. Together, We Fight the Virus. The Government of the

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Available

from: https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/eng/index.html. Accessed 30 Jun 2022.

16. Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations,

risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of

coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic

review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;370:m3320. Crossref

17. Male V. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol 2022;22:277-82. Crossref

18. Nir O, Schwartz A, Toussia-Cohen S, et al. Maternal-neonatal

transfer of SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin

G antibodies among parturient women treated with

BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccine during pregnancy. Am

J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2022;4:100492. Crossref

19. Shook LL, Kishkovich TP, Edlow AG. Countering COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy: the “4 Cs”. Am J Perinatol 2022;39:1048-54. Crossref

20. Betsch C, Schmid P, Heinemeier D, Korn L, Holtmann C,

Böhm R. Beyond confidence: development of a measure

assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination.

PLoS One 2018;13:e0208601. Crossref

21. Chau CY. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy and challenges

to mass vaccination. Hong Kong Med J 2021;27:377-9. Crossref

22. Skjefte M, Ngirbabul M, Akeju O, et al. COVID-19 vaccine

acceptance among pregnant women and mothers of young

children: results of a survey in 16 countries. Eur J Epidemiol

2021;36:197-211. Crossref

23. Gencer H, Özkan S, Vardar O, Serçekuş P. The effects of

the COVID-19 pandemic on vaccine decisions in pregnant

women. Women Birth 2022;35:317-23. Crossref

24. Shamshirsaz AA, Hessami K, Morain S, et al. Intention to

receive COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Am J Perinatol 2022;39:492-500. Crossref

25. Hosokawa Y, Okawa S, Hori A, et al. The prevalence of

COVID-19 vaccination and vaccine hesitancy in pregnant

women: an internet-based cross-sectional study in Japan. J

Epidemiol 2022;32:188-94. Crossref

26. Chervenak FA, McCullough LB, Grünebaum A. Reversing

physician hesitancy to recommend COVID-19 vaccination

for pregnant patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;226:805-12. Crossref

27. Wang K, Wong EL, Cheung AW, et al. Influence of vaccination

characteristics on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among

working-age people in Hong Kong, China: a discrete choice

experiment. Front Public Health 2021;9:793533. Crossref

28. Iacobucci G. COVID-19 and pregnancy: vaccine hesitancy

and how to overcome it. BMJ 2021;375:n2862. Crossref

29. Hospital Authority. Public hospital pertussis vaccination

programme for pregnant women. Jun 28, 2020. Available

from: https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/cc/pertussis_press_release_en.pdf. Accessed 29 Jun 2023.