Hong Kong Med J 2024 Apr;30(2):139–46 | Epub 25 Mar 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Comparison of clinical characteristics between

ACOSOG Z0011–eligible cohort and sentinel lymph node–positive breast cancer patients in Hong Kong

Vivian Man, FCSHK, FRCSEd; Ava Kwong, FCSHK, FRCS

Department of Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Ava Kwong (avakwong@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The American College of Surgeons

Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 trial resulted

in de-escalation of axillary surgery among early-stage

breast cancer patients with low-volume

sentinel lymph node (SLN) disease undergoing

breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy.

Nevertheless, the mastectomy rate in the Chinese

population remains high. This study compared the

clinical characteristics of the ACOSOG Z0011–eligible cohort with SLN-positive breast cancer

patients in Hong Kong.

Methods: This retrospective analysis of a

prospectively maintained database at a university-affiliated

breast cancer centre in Hong Kong was

performed from June 2014 to May 2019. The

database included all patients with clinical tumour

(T) stage T1 or T2 invasive breast carcinoma, no

palpable adenopathy, one or two positive SLNs on

histological examination, and no prior neoadjuvant

systemic treatment. Comparisons were made

between the mastectomy and breast-conserving

treatment groups in our cohort, along with the

sentinel-alone arm in the ACOSOG Z0011 trial.

Results: One hundred and seventy-one patients met

the inclusion criteria: 112 underwent mastectomy and 59 underwent breast-conserving treatment.

Our mastectomy group had higher prevalences

of T2 tumours (P<0.001), lymphovascular

invasion (P<0.001), and SLN macrometastases

(P=0.004) compared with the ACOSOG Z0011

cohort. However, in our patient population, mean

pathological size slightly differed between the

mastectomy and breast-conserving treatment groups

(2.2 cm vs 1.8 cm; P=0.005). Other histopathological

features were similar.

Conclusion: This study demonstrated that

clinicopathological features were comparable

between SLN-positive breast cancer patients

undergoing mastectomy and those undergoing

breast-conserving treatment. Low-risk SLN-positive

mastectomy patients may safely avoid completion

axillary lymph node dissection.

New knowledge added by this study

- Despite the high rate of mastectomy in Hong Kong, a small proportion of node-positive breast cancer patients met the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 eligibility criteria to forgo axillary lymph node dissection.

- Sentinel lymph node–positive breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy displayed clinicopathological features similar to those undergoing breast-conserving treatment in Hong Kong.

- By expanding the AMAROS trial (After Mapping of the Axilla: Radiotherapy Or Surgery?) eligibility to include ACOSOG Z0011–ineligible mastectomy patients, more patients could avoid axillary lymph node dissection with adjuvant radiotherapy, potentially reducing morbidity.

- Further studies are necessary to explore when adjuvant axillary radiotherapy is indicated among mastectomy patients with low axillary nodal burden.

Introduction

The evolution of optimal axillary management for

breast cancer patients has led to emphasis on the

de-escalation of axillary surgery and minimisation

of surgical morbidity. Favourable results from

the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 phase 3 randomised

clinical trials have redefined the indications for

completion axillary lymph node dissection (ALND)

in patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes

(SLNs). Early-stage breast cancer patients who

undergo upfront breast-conserving surgery and have one or two positive SLNs can safely forgo

ALND while maintaining good overall survival and

disease-free survival.1 2 Consequently, the ASCO

(American Society of Clinical Oncology)3 and the

NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network)4

have revised their clinical practice guidelines to

recommend against completion ALND in this

subset of patients. Although this guidance has led

to a significant decline in the rate of completion

ALND among ACOSOG Z0011–eligible patients,5 6 7

a similar reduction was observed among patients

undergoing mastectomy.8 9 This reduction was

particularly pronounced among patients with SLN

micrometastases.8 Further evidence was obtained

in the phase 3 IBCSG (International Breast Cancer

Study Group) 23-01 randomised controlled trials,

where approximately 10% of patients with SLN

micrometastases underwent mastectomy; subgroup

analysis demonstrated that disease-free survival

among patients without axillary dissection was non-inferior

to those with axillary dissection after 10

years of follow-up.10 11 Similarly, in the AMAROS

trial (After Mapping of the Axilla: Radiotherapy

Or Surgery?), 17% of patients with tumour (T)

staging T1 to T2 primary breast cancer underwent

mastectomy.12 Axillary radiotherapy led to an oncological outcome comparable to completion ALND but was associated with a lower rate of lymphoedema.

In Hong Kong, factors such as the relatively

small breast sizes among Chinese women13 and more

conservative cultural attitudes13 14 have contributed to

a higher rate of mastectomy. The decision to perform

mastectomy has prevented a substantial number of

breast cancer patients from meeting the ACOSOG

Z0011 criteria. Our previous study evaluated the

applicability of ACOSOG Z0011 criteria in Hong

Kong.15 Patients with clinical nodal (N) staging N0

breast cancer and one or more positive SLNs were

stratified into eligible and ineligible groups according

to the ACOSOG Z0011 criteria, with 93% of patients

in the ineligible group underwent mastectomy.15

Importantly, only 24% of patients in that study met

the ACOSOG Z0011 criteria and could potentially

avoid ALND.15 Therefore, it is important to identify a

low-risk subset of SLN-positive mastectomy patients

who could benefit from this non-ALND approach.

This retrospective study was conducted to compare

the clinical characteristics of SLN-positive breast

cancer patients in Hong Kong with the ACOSOG

Z0011–eligible cohort.

Methods

Patient recruitment

This retrospective analysis of a prospectively

maintained database was conducted at Queen Mary

Hospital, a university-affiliated tertiary breast cancer

centre in Hong Kong, from June 2014 to May 2019.

Potentially eligible patients in the database were

identified by an independent research assistant

according to whether they met the ACOSOG Z0011

criteria, irrespective of breast surgery type. Patients

were excluded if they had positive non-SLNs or

positive SLNs only detected by immunohistochemical

staining. Relevant data were extracted in July 2020

and missing information was verified using the

Clinical Management System, a central computer

system for medical records across public hospitals

in Hong Kong. Recruited patients were divided into

two groups, namely, the mastectomy group and the

breast-conserving treatment (ie, ACOSOG Z0011–eligible) group.

Clinical management and pathological

assessment

All breast cancer patients underwent mammography

and ultrasound of the breasts and axillae for clinical

tumour and nodal staging. Sentinel lymph node

biopsy (SLNB), offered to patients with clinically

node-negative disease, was performed with a dual

tracer of radioisotope and patent blue dye. Sentinel

lymph nodes were defined as lymph nodes with

ex vivo gamma probe counts exceeding 10% of the highest ex vivo reading or lymph nodes that

displayed blue staining. Non-SLNs were defined as

suspicious nodes that were neither hot (high gamma

probe counts) nor blue-stained during SLNB,

or nodes that were removed during completion

ALND. During the study period, intraoperative

frozen sections of SLNs or suspicious non-SLNs

were routinely collected; these were analysed

by standard haematoxylin and eosin staining.

Immunohistochemistry was performed in cases

of suspected nodal metastasis. Completion ALND

was conducted if frozen or paraffin sections showed

evidence of nodal metastasis. All final pathological

results were reviewed in multidisciplinary meetings.

The pathologies of SLNs were considered normal or

containing one of the following: macrometastases

(>2 mm), micrometastases (>0.2 to ≤2 mm), or

isolated tumour cells (≤0.2 mm). For patients

undergoing breast-conserving surgery, ‘no ink on

tumour’ was regarded as an adequate resection

margin16; alternatively, a second operation was

performed to ensure a clear resection margin.

Adjuvant treatment was administered by breast

oncology specialists according to decisions made in

multidisciplinary meetings.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographic characteristics and tumour

characteristics were retrieved from database records;

percentages were calculated. Missing information

was evaluated and managed by pairwise deletion.

Comparisons were made between the mastectomy

and breast-conserving treatment groups in our

cohort, along with the sentinel-alone arm in the

ACOSOG Z0011 trial (n=436, in intention to treat).1 2

Analyses followed the per-protocol approach and

calculations were performed with SPSS software

(Windows version 24.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY],

United States). Comparisons between cohorts were

conducted with Student’s t test or the Chi squared

test, as appropriate. Human epidermal growth

factor receptor 2 (HER2) status was not assessed

in the ACOSOG Z0011 study; therefore, HER2

statuses were only compared within our cohort. The

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC)

breast cancer nomogram,17 a well-validated

prediction tool to assess the likelihood of non–sentinel node metastases18 19 20 (including external

validation in the Chinese population19 20), was used

to calculate probability through an online calculator

that considered nine variables; comparisons were

made between the breast-conserving treatment and

mastectomy groups. P values <0.05 were considered

statistically significant.

Results

In our centre, the ACOSOG Z0011 criteria have been used to manage patients undergoing breast-conserving

surgery since June 2019. From June 2014

to May 2019, 1249 breast cancer patients underwent

SLNB in our institution; 171 patients (13.7%) met

the study inclusion criteria of clinical T1 or T2

invasive breast cancer and one or two positive SLNs.

One hundred and twelve patients (65.5%) underwent

mastectomy and 59 patients (34.5%) underwent

breast-conserving treatment. The median follow-up

period was 58 months (range, 25-84).

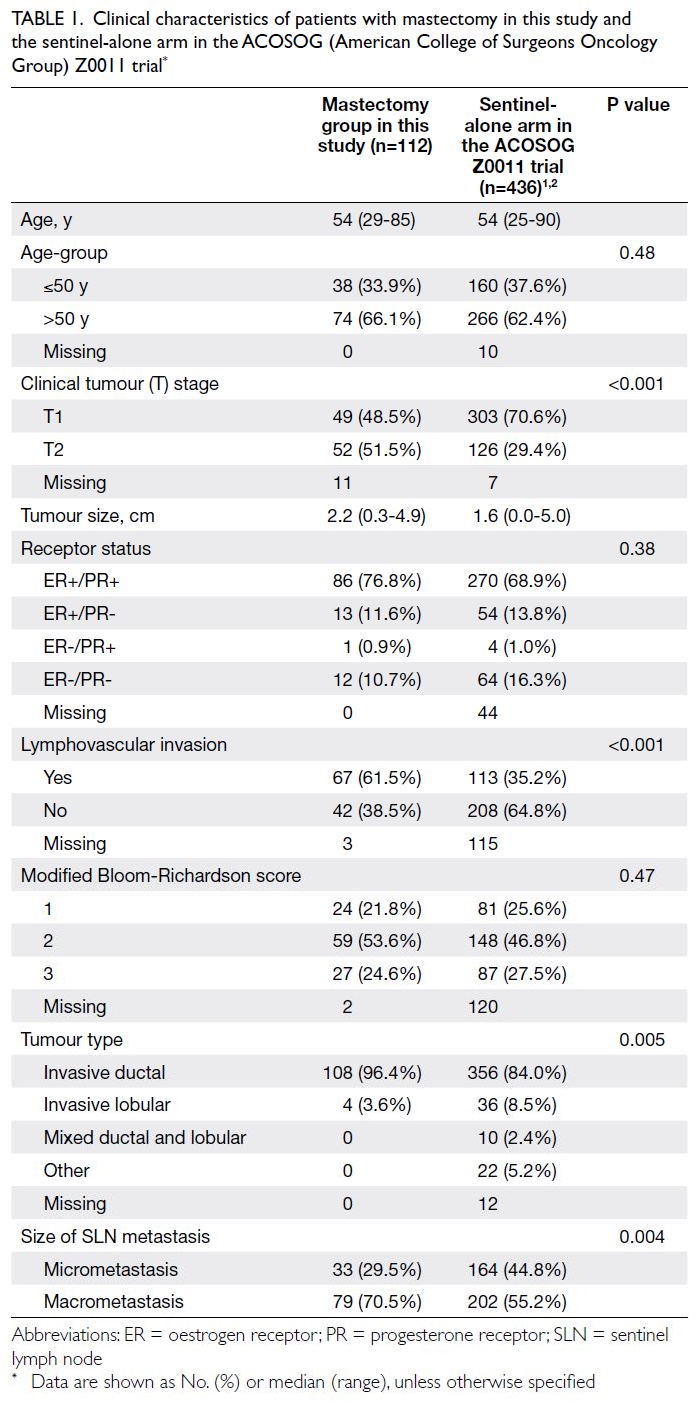

Our mastectomy group versus the sentinel-alone

arm in the ACOSOG Z0011 trial

Patient demographic characteristics and tumour

characteristics of our mastectomy group and the

sentinel-alone arm in the ACOSOG Z0011 trial

are presented in Table 1. Invasive ductal carcinoma

was more common in our patient population than

in the ACOSOG Z0011 group. A higher prevalence

of clinical T2 breast cancers (~50%) was observed in

our mastectomy group (P<0.001). There were also

significantly more patients with lymphovascular

invasion in our cohort than in the sentinel-alone arm

in the ACOSOG Z0011 trial (P<0.001). Although

nearly half of the original ACOSOG Z0011 cohort

had micrometastatic SLNs, approximately 70%

of mastectomy patients had macrometastatic

SLNs (P=0.004). These findings suggested that the

clinicopathological profile was more aggressive in

patients requiring mastectomy.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients with mastectomy in this study and the sentinel-alone arm in the ACOSOG (American College of Surgeons Oncology Group) Z0011 trial

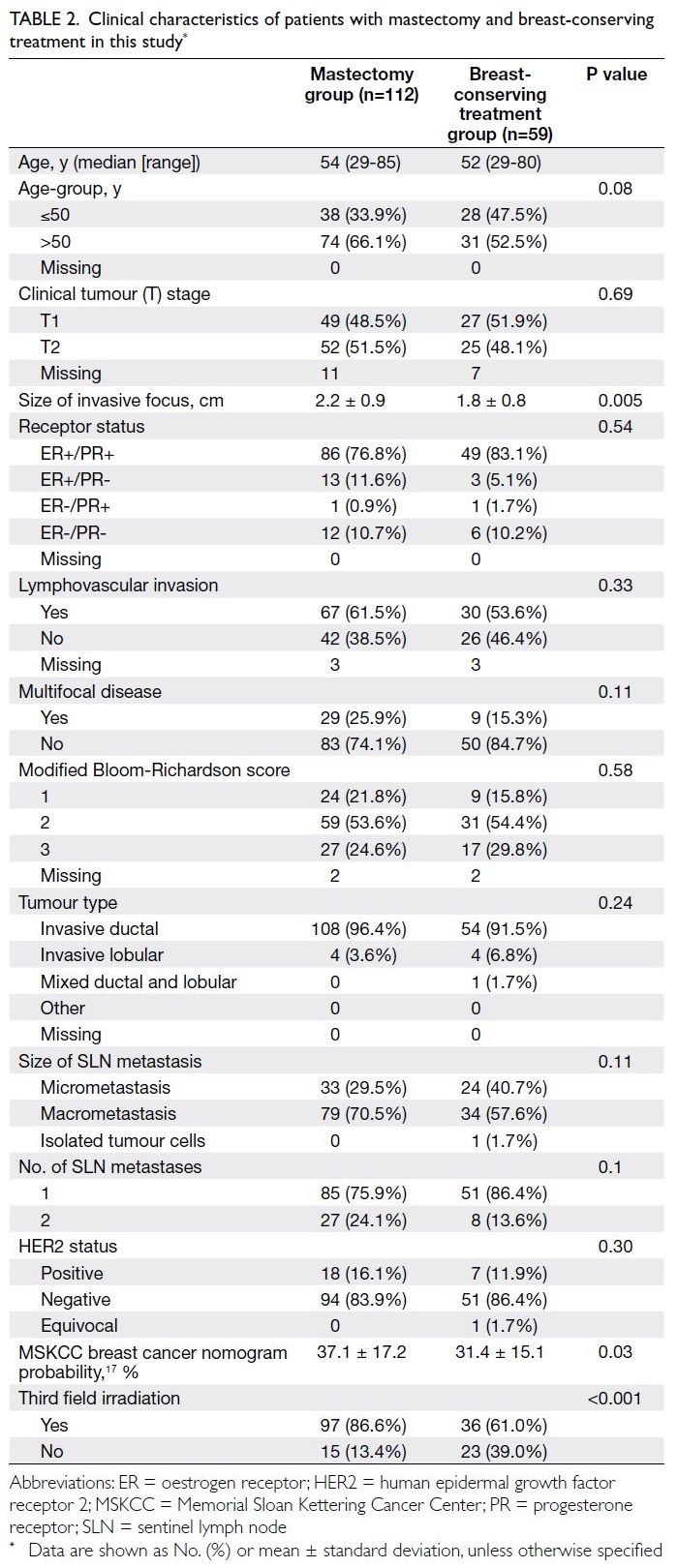

Our mastectomy group versus our breast-conserving

treatment group

In our patient cohort, the mastectomy group

exhibited many clinicopathological characteristics

similar to the breast-conserving treatment group

(Table 2). There were no statistically significant

differences in terms of age, tumour grade,

lymphovascular invasion status, oestrogen receptor/progesterone receptor status, or HER2 status. The

mastectomy group had relatively larger tumours

than the breast-conserving treatment group (mean:

2.2 cm vs 1.8 cm; P=0.005). Although the difference

was not statistically significant, the mastectomy

group tended to have larger proportions of patients

with two metastatic SLNs (24.1% vs 13.6%; P=0.1)

and SLN macrometastases (70.5% vs 57.6%; P=0.11)

than the breast-conserving treatment group.

Furthermore, the MSKCC probability for additional

metastatic non-SLNs was slightly higher in the

mastectomy group than in the breast-conserving

treatment group (37.1% vs 31.4%; P=0.03) [Table 2].

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of patients with mastectomy and breast-conserving treatment in this study

Ninety-seven patients (86.6%) in the

mastectomy group and 45 patients (76.3%) in the

breast-conserving treatment group underwent

completion ALND. Among patients who underwent

mastectomy and completion ALND, 26 patients (26.8%) had additional non-SLN metastases (range,

1-18). In contrast, eight patients (17.8%) in the

breast-conserving treatment group had additional

non-SLN metastases (range, 1-8). There was no statistically significant difference in the rate of

non-SLN metastases between the two treatment

arms (P=0.24). Twenty-nine patients (17.9%)

underwent SLNB alone; 15 of these patients were

in the mastectomy group. Most patients with SLNB

alone had micrometastatic SLNs (89.7%) and one

patient had isolated tumour cells. None of the

patients with SLNB alone experienced recurrence.

Adjuvant treatment

In the mastectomy group, 97 patients (86.6%)

underwent post-mastectomy irradiation targeting

the chest wall and third field regional nodes. Third

field regional nodes refer to level III axillary and

supraclavicular lymph node regions. None of these

patients developed chest wall or axillary recurrence

during the follow-up period. Among the 15 patients

who did not undergo post-mastectomy irradiation,

eight (53.3%) had micrometastatic SLNs and six

(40.0%) had macrometastatic SLNs. There were two

recurrences (13.3%). First, a 38-year-old patient with

one macrometastatic SLN developed ipsilateral chest

wall recurrence 4 years after the index operation;

this recurrence was managed by a second operation.

Second, a patient with two macrometastatic SLNs

refused adjuvant systemic treatment and died of

breast cancer‐related distant metastases. One

hundred and ten patients in the mastectomy group

(98.2%) received adjuvant systemic treatment: 10

patients (8.9%) required chemotherapy only, 22

patients (19.6%) required hormonal treatment

only, and 78 patients (69.6%) required both of these

treatments. Seven patients (6.3%) in the mastectomy

group developed distant recurrence, and there were

three (2.7%) breast cancer–related deaths.

In the breast-conserving treatment group, 58

of the 59 patients underwent adjuvant whole-breast

irradiation; 61.0% of these patients underwent

additional third field nodal irradiation. Fifty-eight

patients (98.3%) in the breast-conserving treatment

group received adjuvant systemic treatment

involving hormonal therapy and/or chemotherapy.

Three patients (5.1%) had distant recurrence; among

them, one (1.7%) died at 39 months after the initial

diagnosis. One patient experienced ipsilateral breast

recurrence at 30 months and underwent completion

mastectomy.

Discussion

The favourable oncological results of the ACOSOG

Z0011 trial1 2 have challenged the conventional

approach of performing completion ALND in

patients with SLN metastases. Patients with one

or two SLN metastases who underwent breast-conserving

surgery, whole-breast irradiation, and

adjuvant systemic treatment could safely forgo

completion ALND. This paradigm shift has led to substantial de-escalation of axillary surgery

worldwide.5 A meta-analysis by Schmidt-Hansen

et al,21 which involved 2020 patients and findings

from the IBCSG 23-0110 11 and the AATRM (Agència

d’Avaluació de Tecnologia i Recerca Mèdiques)

048/13/200022 trials, concluded that SLNB alone

was sufficient for locoregional control in early breast

cancer, without adverse effects on survival.

Limitations of the ACOSOG Z0011 study

Despite widespread adoption of the ACOSOG Z0011

criteria, the study has been criticised in several ways.

The low locoregional relapse rate of 1.5% indicates

that the study was underpowered.23 Furthermore,

significant deviation in the radiotherapy protocol,

such that 18.9% of patients received ‘high tangents’

radiotherapy, has raised questions concerning the

oncological safety of SLNB alone in patients without

third field nodal irradiation.24 Combined with the

insufficient numbers of mastectomy patients in

the IBCSG 23-01,10 11 AMAROS,12 and AATRM

048/13/200022 trials, it has been unclear whether

this non-ALND approach can be extrapolated to

SLN-positive breast cancer patients who undergo

mastectomy with or without radiotherapy.

Aggressive tumour characteristics among mastectomy patients and local or regional failure rate

In this study, we compared the clinicopathological

characteristics among our mastectomy group, our

breast-conserving treatment group, and the sentinel-alone

arm in the original ACOSOG Z0011 study.

Unsurprisingly, our mastectomy group exhibited

more aggressive tumour characteristics than the

sentinel-alone arm in the Western population;

specifically, it had a larger tumour size, more frequent

lymphovascular invasion, and a greater proportion

of patients with SLN macrometastases. These

differences in clinicopathological features have also

been reported in Western populations. For example,

Hennigs et al8 analysed a large German cohort that

included 4093 SLN-positive mastectomy patients.

Compared with the entire study cohort of 166 074

patients, T2 tumour and lymphovascular invasion

were more commonly found in patients requiring

mastectomy. Additionally, the study by Milgrom et al25

included 535 early-stage breast cancer patients with

a positive SLNB and no ALND. In their mastectomy

group, patients had significantly larger tumours and

more frequently displayed multifocal/multicentric

disease. However, these adverse pathological features

among mastectomy patients did not justify a more

aggressive axillary approach. Similarly, the low rates

of local and regional failure observed in our cohort

were consistent with previous reports, suggesting

that axillary-specific treatment can be considered in this group of patients with low-volume SLN

disease.25 26 27 28 Debate persists regarding the

comparatively large proportions of patients with

micrometastatic disease in the original ACOSOG

Z0011 trial1 2 and other studies.25 26 Cowher et al29

published a retrospective analysis of patients

who underwent mastectomy and conservative

axillary regional excision (ie, removal of SLNs and

other palpable nodes). Among 144 patients with

pathological N1 disease, a small proportion (24%)

had micrometastatic disease; only three axillary

recurrences (2.1%) were reported.29 Notably, the

low locoregional failure rate was not attributed to

post-mastectomy irradiation25 26 27 28 29 or increased use of

chemotherapy.26 27 28

Intrinsic differences in tumour characteristics between different patient populations

In our previous study, we demonstrated differences

in clinical characteristics between Asian and

Western populations.15 In the present study, our

breast-conserving treatment group had a higher

rate of clinical T2 tumours and more frequent

lymphovascular invasion compared with the

Western population. Similar findings were observed

in Korean30 and Japanese31 studies, which revealed

larger and higher-grade tumours, increased

lymphovascular permeation, and more frequent

SLN macrometastases. Despite these disparities, the

Korean30 and Japanese31 studies both demonstrated

safe application of ACOSOG Z0011 criteria in

Asia, with low incidences of disease recurrence.

These intrinsic differences in tumour characteristics

between Eastern and Western populations have

presumably reduced the gap in clinicopathological

features between patients undergoing mastectomy

and those undergoing breast-conserving surgery.

In the head-to-head comparison between our

mastectomy cohort and our breast-conserving

treatment group, the only notable difference involved

the mean pathological size of the invasive focus

(2.2 cm vs 1.8 cm; P=0.005); the clinical tumour

stage distribution did not differ (P=0.69) [Table 2].

The small difference in mean MSKCC breast cancer

nomogram probability (37.1% vs 31.4%; P=0.03)

could also be related to the difference in pathological

size, which is one of the nine variables considered

in the nomogram. Therefore, we believe that a non-ALND approach in this low-risk subset of SLN-positive

mastectomy patients is acceptable.

Residual non–sentinel lymph node metastasis in non–axillary lymph node dissection approach

The primary concern regarding extrapolation of this

non-ALND approach is the risk of undertreatment

for patients with an extensive nodal burden. The original ACOSOG Z0011 trial revealed a non-SLN

macrometastasis rate of 27.3% in the ALND group.1 2

The AMAROS trial also showed that 33% of patients

in the ALND group had additional positive lymph

nodes.12 Importantly, the axillary recurrence rate

remained low in both of these studies. In our

SLN-positive mastectomy and breast-conserving

treatment groups, the proportions of patients with

additional non-SLN metastases were 26.8% and

17.8%, respectively. Among patients undergoing

adjuvant irradiation and adjuvant systemic

treatment, it is likely that some non-SLN metastases

do not progress to clinically detectable disease.

Limitations of this study

This study had several limitations. First, its

retrospective design could result in recall bias

and the potential for missing clinical information.

Although data from the ACOSOG Z0011 trial were

limited with respect to HER2 status, extracapsular

extension, and multifocality, we attempted to

mitigate this issue by including some of the affected

variables in the comparison of our mastectomy and

breast-conserving treatment groups. Second, we

could not address the need for post-mastectomy

irradiation among patients in this study. The value

of such irradiation for breast cancer patients with

<4 positive lymph nodes remains controversial. The

meta-analysis by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’

Collaborative Group,32 which included 1314 breast

cancer patients with one to three positive nodes

after mastectomy and ALND, suggested that

radiotherapy provided oncological benefit in terms

of locoregional recurrence, overall recurrence,

and breast cancer mortality. However, this meta-analysis

has been criticised for including some very

early studies from the 1970s, in which the reported

recurrence rates were much higher than rates in

later studies. In 2016, a focused update by the

American Society of Clinical Oncology, American

Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of

Surgical Oncology acknowledged the use of post-mastectomy

radiotherapy for this group of patients

but recommended clinical judgement for patients

with a low risk of locoregional recurrence.33 In our centre, post-mastectomy irradiation was generally

administered to patients with pathological N1

disease during the study period; 86.6% of patients in

the present study underwent adjuvant radiotherapy.

Considering the similarities in clinicopathological

features and adjuvant systemic treatment use

between our SLN-positive mastectomy and breast-conserving

treatment groups, we suspect that it is

safe for selected low-risk SLN-positive mastectomy

patients to forgo ALND through the expansion of

AMAROS eligibility12 to ACOSOG Z0011–ineligible

patients. Several ongoing randomised studies, such

as the English POSNOC (POsitive Sentinel NOde: adjuvant therapy alone versus adjuvant therapy

plus Clearance or axillary radiotherapy)34 and the

Dutch BOOG 2013-07,35 are recruiting breast

cancer patients who undergo mastectomy and

have a maximum of two to three positive SLNs;

these studies aim to compare completion axillary

treatment (ALND or axillary radiotherapy) and the

lack of completion axillary treatment. Additionally,

the SINODAR-ONE trial36 recently published their

subgroup analysis and found non-inferior overall

survival and recurrence-free survival among

mastectomy patients receiving SLNB and ALND.

The ongoing studies are expected to provide more

robust evidence concerning the optimal treatment

for SLN-positive mastectomy patients.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the clinicopathological

similarities between SLN-positive mastectomy and

breast-conserving treatment groups among breast

cancer patients in Hong Kong. Cautious application

of the non-ALND approach in mastectomy patients

with low-volume SLN disease is reasonable,

considering the low locoregional recurrence

rate. However, additional research is needed

to standardise the adjuvant post-mastectomy

radiotherapy protocol, especially among patients

who forego ALND.

Author contributions

Concept or design: V Man.

Acquisition of data: V Man.

Analysis or interpretation of data: V Man.

Drafting of the manuscript: Both authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: A Kwong.

Acquisition of data: V Man.

Analysis or interpretation of data: V Man.

Drafting of the manuscript: Both authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: A Kwong.

Both authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Declaration

This study has been presented and awarded the Young Investigator Award Best Scientific Paper in the Hong Kong Society of Breast Surgeons 5th Annual Scientific Meeting (19 September 2021, Hong Kong).

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster, Hong Kong (Ref No.: HKU/HA HKW UW 09-045). Written informed consent was obtained from patients for all treatments, procedures, and publication.

References

1. Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, et al. Axillary

dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive

breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized

clinical trial. JAMA 2011;305:569-75. Crossref

2. Guiliano AE, Ballman KV, McCall L, et al. Effect of axillary

dissection vs no axillary dissection on 10-year overall

survival among women with invasive breast cancer and

sentinel node metastasis: the ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance)

randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:918-26. Crossref

3. Lyman GH, Termin S, Edge SB, et al. Sentinel lymph

node biopsy for patients with early-stage breast cancer:

American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice

guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1365-83. Crossref

4. Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Balassanian R, et al. NCCN

guidelines insights: breast cancer, version 1.2017. J Natl

Compr Canc Netw 2017;15:433-51. Crossref

5. Camp MS, Greenup RA, Taghian A, et al. Application of

ACOSOG Z0011 criteria reduces perioperative costs. Ann

Surg Oncol 2013;20:836-41. Crossref

6. Delpech Y, Bricou A, Lousquy R, et al. The exportability

of the ACOSOG Z0011 criteria for omitting axillary

lymph node dissection after positive sentinel lymph node

biopsy findings: a multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol

2013;20:2556-61. Crossref

7. Verheuvel NC, Voogd AC, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Roumen RM.

Potential impact of application of Z0011 derived criteria to

omit axillary lymph node dissection in node positive breast

cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016;42:1162-8. Crossref

8. Hennigs A, Riedel F, Feißt M, et al. Evolution of the use of

completion axillary lymph node dissection in patients with

T1/2N0M0 breast cancer and tumour-involved sentinel

lymph nodes undergoing mastectomy: a cohort study. Ann

Surg Oncol 2019;26:2435-43. Crossref

9. Poodt IG, Spronk PE, Vugts G, et al. Trends on axillary

surgery in nondistant metastatic breast cancer patients

treated between 2011 and 2015: a Dutch population-based

study in the ACOSOG-Z0011 and AMAROS era. Ann

Surg 2018;268:1084-90. Crossref

10. Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, et al. Axillary dissection

versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node

micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised

controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:297-305. Crossref

11. Galimberti V, Cole BF, Viale G, et al. Axillary dissection

versus no axillary dissection in patients with breast cancer

and sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01):

10-year follow-up of a randomised, controlled phase 3

trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1385-93. Crossref

12. Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, et al.

Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive

sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981-22023

AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase

3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1303-10. Crossref

13. Sinnadurai S, Kwong A, Hartman M, et al. Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy in young women with breast cancer in Asian settings. BJS Open 2018;3:48-55. Crossref

14. Chan SW, Cheung C, Chan A, Cheung PS. Surgical options

for Chinese patients with early invasive breast cancer: data

from the Hong Kong Breast Cancer Registry. Asian J Surg 2017;40:444-52.Crossref

15. Man V, Lo MS, Kwong A. The applicability of the ACOSOG

Z0011 criteria to breast cancer patients in Hong Kong.

Chin Clin Oncol 2021;10:27. Crossref

16. Moran MS, Schnitt SJ, Giuliano AE, et al. Society of

Surgical Oncology–American Society for Radiation

Oncology consensus guideline on margins for breast-conserving

surgery with whole-breast irradiation in stages I

and II invasive breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:704-16. Crossref

17. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Breast cancer

nomogram: breast additional non-SLN metastases.

Available from: https://nomograms.mskcc.org/breast/BreastAdditionalNonSLNMetastasesPage.aspx. Accessed 19 Mar 2024.

18. Gur AS, Unal B, Ozbek U, et al. Validation of breast cancer

nomograms for predicting the non–sentinel lymph node

metastases after a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in a

multi-center study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010;36:30-5. Crossref

19. Kuo YL, Chen WC, Yao WJ, et al. Validation of Memorial

Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center nomogram for prediction

of non–sentinel lymph node metastasis in sentinel lymph

node positive breast cancer patients: an international

comparison. Int J Surg 2013;11:538-43. Crossref

20. Bi X, Wang Y, Li M, et al. Validation of the Memorial

Sloan Kettering Cancer Center nomogram for predicting

non–sentinel lymph node metastasis in sentinel lymph

node–positive breast-cancer patients. Onco Targets Ther

2015;8:487-93. Crossref

21. Schmidt-Hansen M, Bromham N, Hasler E, Reed MW.

Axillary surgery in women with sentinel node–positive

operable breast cancer: a systematic review with meta-analyses.

Springerplus 2016;5:85. Crossref

22. Solá M, Alberro JA, Fraile M, et al. Complete axillary lymph

node dissection versus clinical follow-up in breast cancer

patients with sentinel node micrometastasis: final results

from the multicenter clinical trial AATRM 048/13/2000.

Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:120-7. Crossref

23. Huang TW, Kuo KN, Chen KH, et al. Recommendation for

axillary lymph node dissection in women with early breast

cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a systematic review

and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials using

the GRADE system. Int J Surg 2016;34:73-80. Crossref

24. Jagsi R, Chadha M, Moni J, et al. Radiation field design

in the ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) trial. J Clin Oncol

2014;32:3600-6. Crossref

25. Milgrom S, Cody H, Tan L, et al. Characteristics and

outcomes of sentinel node–positive breast cancer patients

after total mastectomy without axillary-specific treatment. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:3762-70. Crossref

26. FitzSullivan E, Bassett RL, Kuerer HM, et al. Outcomes

of sentinel lymph node–positive breast cancer patients

treated with mastectomy without axillary therapy. Ann

Surg Oncol 2017;24:652-9. Crossref

27. Snow R, Reyna C, Johns C, et al. Outcomes with and without

axillary node dissection for node-positive lumpectomy and

mastectomy patients. Am J Surg 2015;210:685-93. Crossref

28. Joo JH, Kim SS, Son BH, et al. Axillary lymph node

dissection does not improve post-mastectomy overall or

disease-free survival among breast cancer patients with 1-3

positive nodes. Cancer Res Treat 2019;51:1011-21. Crossref

29. Cowher MS, Grobmyer SR, Lyons J, O’Rourke C, Baynes D,

Crowe JP. Conservative axillary surgery in breast cancer

patients undergoing mastectomy: long-term results. J Am

Coll Surg 2014;218:819-24. Crossref

30. Jung J, Han W, Lee ES, et al. Retrospectively validating the

results of the ACOSOG Z0011 trial in a large Asian Z0011-eligible cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;175:203-15. Crossref

31. Kittaka N, Tokui R, Ota C, et al. A prospective feasibility

study applying the ACOSOG Z0011 criteria to Japanese

patients with early breast cancer undergoing breast-conserving

surgery. Int J Clin Oncol 2018;23:860-6. Crossref

32. EBCTCG (Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative

Group); McGale P, Taylor C, et al. Effect of radiotherapy

after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10-year

recurrence and 20-year breast cancer mortality: meta-analysis

of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22

randomised trials. Lancet 2014;383:2127-35. Crossref

33. Recht A, Comen EA, Fine RE, et al. Postmastectomy

radiotherapy: an American Society of Clinical Oncology,

American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of

Surgical Oncology focused guideline update. Pract Radiat

Oncol 2016;6:e219-34. Crossref

34. Goyal A, Dodwell D. POSNOC: a randomised trial looking

at axillary treatment in women with one or two sentinel

nodes with macrometastases. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol)

2015;27:692-5. Crossref

35. van Roozendaal LM, de Wilt JH, van Dalen T, et al. The

value of completion axillary treatment in sentinel node

positive breast cancer patients undergoing a mastectomy:

a Dutch randomized controlled multicentre trial (BOOG

2013-07). BMC Cancer 2015;15:610. Crossref

36. Tinterri C, Canavese G, Gatzemeier W, et al. Sentinel

lymph node biopsy versus axillary lymph node dissection

in breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy with one

to two metastatic sentinel lymph nodes: sub-analysis of the

SINODAR-ONE multicentre randomized clinical trial and

reopening of enrolment. Br J Surg 2023;110:1143-52. Crossref