Hong Kong Med J 2019 Oct;25(5):372–81 | Epub 9 Oct 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Sexual function, self-esteem, and general well-being in

Chinese adult survivors of childhood cancers: a cross-sectional survey

CF Ng, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Cindy YL Hong, MSc1;

Becky SY Lau, MPH1; Jeremy YC Teoh, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Samuel CH Yee, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

Alex WK Leung, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2; John WM Yuen, PhD3

1 SH Ho Urology Centre, Department of

Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Paediatrics Oncology Team, Department

of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

3 School of Nursing, The Hong Kong

Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof CF Ng (ngcf@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This study

was conducted to evaluate sexual function in adult survivors of

childhood cancers and investigate possible relationships between sexual

function and quality of life, as measured by general well-being,

self-esteem, body image, and depressive symptoms.

Methods: This cross-sectional

survey was performed in our centre from 14 August 2015 to 8 September

2017. Adult patients who had a history of childhood cancers, and who

were disease-free for >3 years, were approached for the study during

clinical follow-up. Clinical information was collected from medical

records. Self-administered questionnaires regarding quality of life and

sexual functioning were given to the patients and resulting data were

analysed.

Results: Two hundred patients

agreed to participate in the study. The overall response rate was 64.8%.

Ninety-one (45.5%) patients were women, and the mean age was 25.4 ± 5.57

years. The overall sexual functioning score was 28.3 ± 20.09.

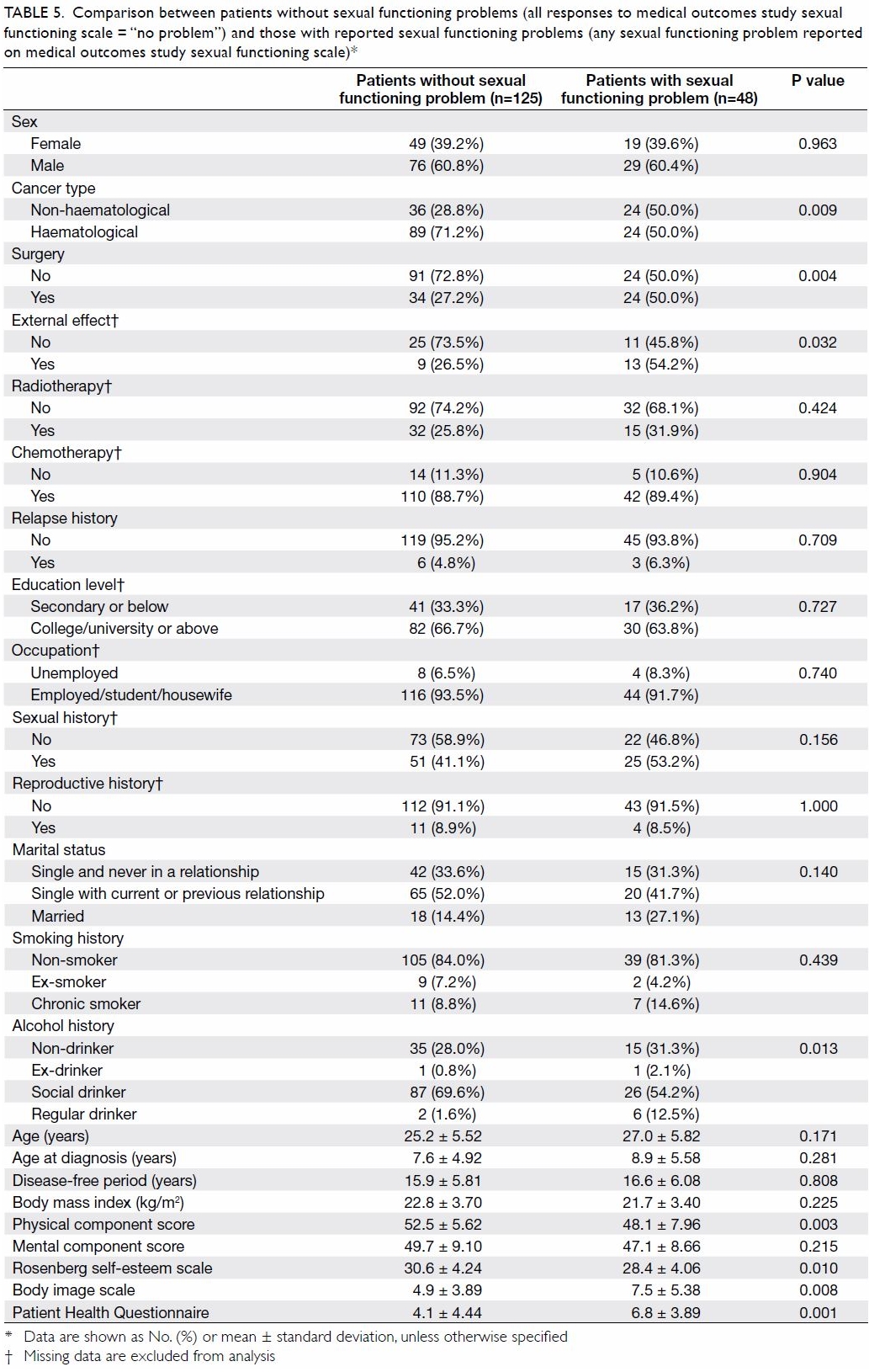

Forty-eight (24.0%) patients reported at least one sexual problem. Among

patients who reported no sexual problems, more had haematological

cancers (P=0.009), fewer underwent surgery (P=0.004), fewer underwent

surgery with external effects (P=0.032), and fewer were regular social

drinkers (P=0.013); additionally, they had a higher mean Rosenberg

self-esteem scale score (P=0.010), lower mean body image scale score

(P=0.008), and lower mean Patient Health Questionnaire score (P=0.001).

Conclusion: Aspects of life

beyond disease condition and physical function should be considered in

adult survivors of childhood cancers. Appropriate referral and

intervention should be initiated for these patients when

necessary.

New knowledge added by this study

- Approximately one-quarter of young Chinese cancer survivors in Hong Kong had at least one sexual problem.

- Sexual problems were more common in men, in patients diagnosed with cancer at an older age, and in patients who were married or had a history of sexual experiences.

- The presence of sexual problems in adult survivors of childhood cancer was significantly associated with a history of surgery, as well as a history of surgery with external effects; patients with sexual problems generally had lower physical well-being scores, lower self-esteem scores, higher body image scale scores, and an increased number of depressive symptoms.

- Rather than entirely focusing on disease condition and physical function, physicians and medical staff should ensure that they consider other aspects of life in survivors of childhood cancer, to support holistic recovery of these patients.

- Multidisciplinary care, such as involvement of adult urologists and gynaecologists, would facilitate the transition of these young cancer survivors into adult life.

Introduction

Sexual health, defined by the World Health

Organization as a state of physical, emotional, mental and social

well-being related to sexuality, has been recognised as an integral part

of overall health and quality of life.1

Improvements in disease understanding and treatment options have changed

the circumstances involved in the management of sexual dysfunction and

reproductive medicine.

With improvements in cancer care, the long-term

outlook of paediatric cancer patients has significantly improved in recent

decades.2 However, there is

increasing awareness of the problems experienced by these cancer survivors

when they reach adulthood.3

Potential problems experienced by adult survivors of childhood cancers

include (1) physical and functional complications related to the cancer

and its therapies (eg, delay in pubertal development, hormonal production,

azo-/oligospermia, ovarian failure, and vaginal stenosis); and (2)

psychosocial problems related to the cancer and its therapies (eg,

concerns regarding cancer recurrence, self-esteem, and relationship

problems). These physical and psychological dysfunctions affect the sexual

health and overall health of the patients. The findings of many reports

have suggested significant associations between sexual function and health

status,4 and have revealed that

these problems are relatively common among cancer survivors.5 6

Unfortunately, discussions of sexual dysfunction

remain infrequent in traditional Chinese culture. The situation may be

more difficult among young adult cancer survivors. Therefore, information

regarding cancer-related sexual dysfunction, including its prevalence in

the Chinese population, remains limited and may lead to an underestimation

of the seriousness of the problem. To address this lack of knowledge and

facilitate future development of childhood cancer care, this

cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate sexual function in adult

survivors of childhood cancers and the relationships of sexual function

with the general well-being, self-esteem, body image, and depressive

symptoms of these patients.

Methods

Patients

The study was conducted in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki and was performed at The Chinese University of

Hong Kong. The sample size was based on a convenience sample of all

patients that we could recruit during the 2-year study period. Consecutive

patients who were returning to the paediatric oncology clinic for

follow-up and who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were

invited to participate in the study. After patients provided informed

consent, basic demographic data and disease-related information were

collected.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1)

diagnosed with cancer at age <18 years; (2) aged 18 to 40 years at the

time of inclusion in the study; (3) not undergoing treatment and

disease-free >3 years after completing treatment (excluding use of

chemopreventive agents). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1)

original tumours that were hormone-dependent, such as breast cancer; (2)

ongoing sex hormone supplementation; and (3) sensory/cognitive impairment

that would interfere with the patient’s ability to independently complete

the questionnaires.

Questionnaire data collection

A series of self-administered questionnaires were

completed by the patients in a private room in the clinic. The following

questionnaires were used.

Medical outcomes study sexual functioning scale

This is a validated instrument that has been widely

used to identify sexual impairment and dysfunction associated with serious

health conditions or side-effects of treatments.7

It consists of four questions for both male and female patients, which

evaluate sexual problems including lack of interest in sexual activity,

difficulty in becoming aroused, difficulty in relaxing and enjoying sex,

and difficulty in achieving orgasm. Each outcome is measured with an

ordinal scale ranging from 0 (‘not a problem’) to 4 (‘very much a

problem’). The category of ‘not applicable’ was recoded as 0 during

calculation. Total scores were calculated and transformed to a 0-100

scale; a higher score indicates more sexual problems. The questionnaire

was translated and validated by Department of Nursing, The Polytechnic

University of Hong Kong.

General Health Questionnaire Short Form-12

This questionnaire is used for general measurement

of health status in terms of physical component score (PCS) and mental

component score (MCS).8 The summary

scores are calculated based on the standard scoring algorithm described in

the manual9; a higher score

represents better physical or mental health.

Rosenberg self-esteem scale

This tool is commonly used to evaluate self-esteem.10 11

It comprises 10 questions which assess both positive and negative feelings

about the self. Patients respond to questions using a 4-point scale,

ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’; a higher summary

score indicates higher self-esteem.

Body image scale

Body image scale (BIS) is an 11-item scale used to

assess body image changes in cancer survivors after cancer treatment.12 13 Body

image changes can be rated in an ordinal scale ranging from 0 (‘not at

all’) to 3 (‘very much’); a higher total score indicates greater body

image distress.

Patient Health Questionnaire

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is widely used

to measure depressive symptoms. It assesses the extent to which the

symptoms were experienced by the patient in past 2 weeks.14 15 Patients

respond to items using an ordinal scale ranging from 0 (‘not at all’) to 3

(‘nearly every day’). The degree of depression is graded based on the

total score of the nine items: mild (5 ≤ score ≤ 9), moderate (10 ≤ score

≤ 14), and severe (score ≥15).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as counts and

percentages for categorical data, and as means and standard deviations for

continuous data. The Chi squared test, Fisher’s exact test, analysis of

variance, correlation, and simple linear regression methods were used for

simple analyses and subgroup comparisons. More sophisticated analyses were

performed using multiple linear regression and multivariable logistic

regression, to control for potential confounders. All statistical analyses

were performed using SPSS (Windows version 24.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY],

United States). All levels of significance were set at the 0.05 level and

all tests were two-sided. Missing data were excluded from analysis.

Results

Patient demographic characteristics and cancer

treatment histories

The study was performed from 14 August 2015 to 8

September 2017. Three hundred seventy-two consecutive patients were

approached, and 241 patients agreed to participate in the study. The

overall response rate was 64.8%. Forty-one patients were excluded from

analysis due to incomplete data collection or failure to appropriately

meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Therefore, a total of 200 patients

were included in the analysis.

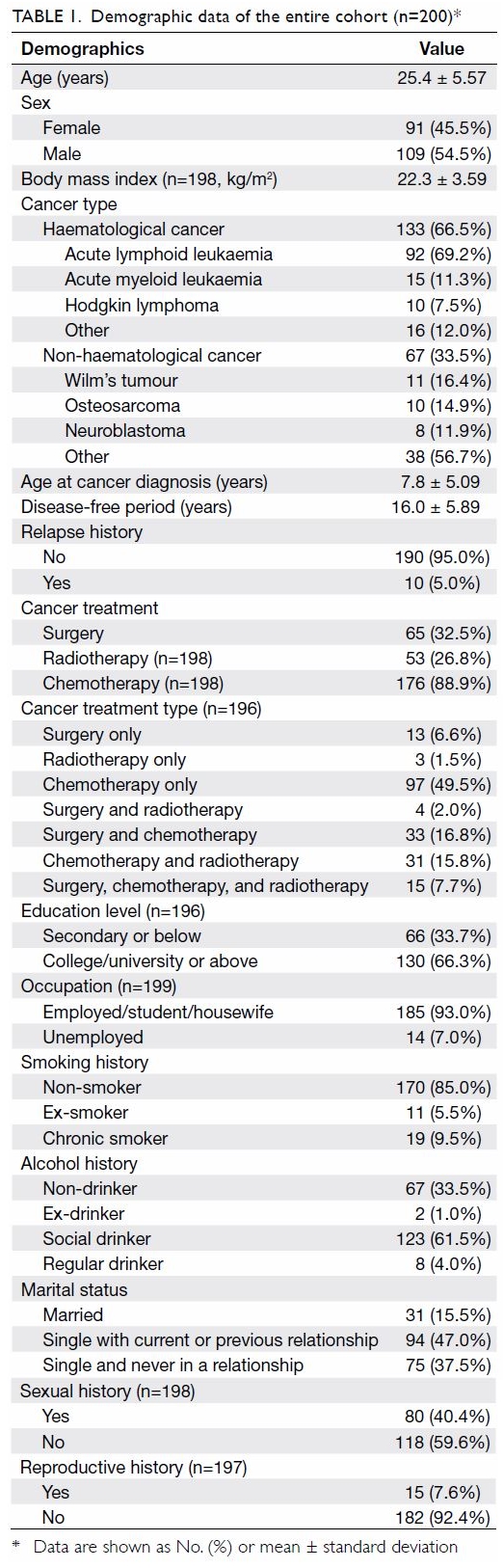

Among the 200 patients, 91 (45.5%) were women; the

mean age of all patients was 25.4 ± 5.57 years, and the mean age at

diagnosis was 7.8 ± 5.09 years. In total, 133 (66.5%) patients had

haematological cancer, among whom 92 (46.0%) had acute lymphoid leukaemia,

15 (7.5%) had acute myeloid leukaemia, and 10 (5.0%) had Hodgkin lymphoma.

Sixty-seven (33.5%) patients had non-haematological cancer, among whom 11

(5.5%) had Wilm’s tumour, 10 (5.0%) had osteosarcoma, and eight (4.0%) had

neuroblastoma. Sixty-five (32.5%) patients underwent surgery, and 23

(11.5%) exhibited visible external effects, such as limb resection.

Fifty-three (26.8%) patients received radiotherapy and 176 (88.9%)

received chemotherapy. Ten (5.0%) patients had experienced cancer relapse.

Thirty-one (15.5%) patients were married, 94 (47.0%) were single with a

current or previous relationship, and 75 (37.5%) were single and had never

been in a relationship (Table 1). Eighty (40.4%) patients reported a history

of sexual experiences and 15 (7.6%) had impregnated their partners or ever

conceived a child.

Sexual impairment and dysfunction related to childhood

cancer and treatment

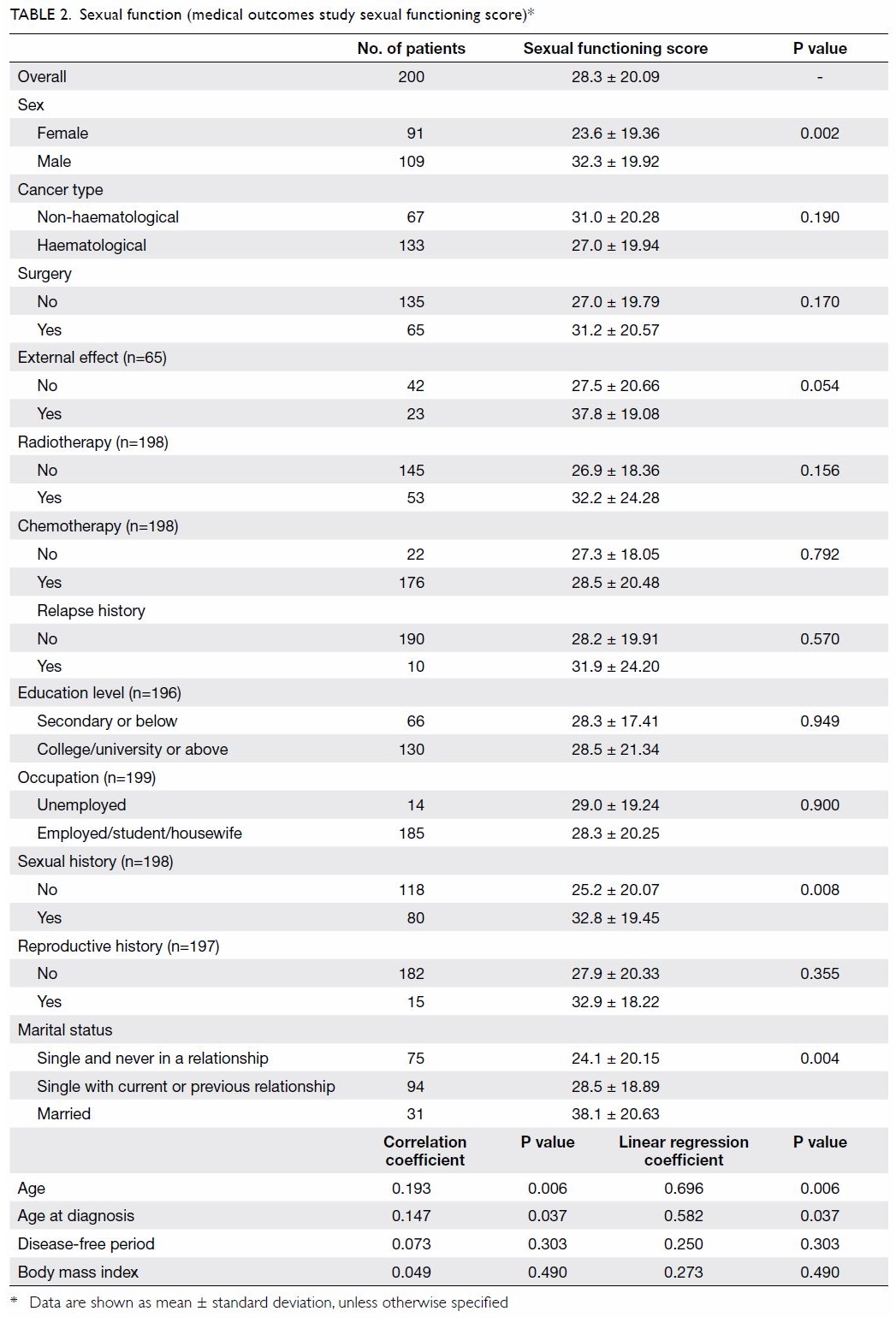

The overall medical outcomes study sexual

functioning score was 28.3 ± 20.09. Men (32.3 ± 19.92) had a significantly

higher mean sexual functioning score (ie, more sexual problems) than women

(23.6 ± 19.36, P=0.002) [Table 2]. Age at the time of this study (r=0.193,

P=0.006) and age at cancer diagnosis (r=0.147, P=0.037) were

significantly positively correlated with sexual functioning score (ie,

more sexual problems). Patients who had a history of sexual experiences

(32.8 ± 19.45, P=0.008) or who had been married (38.1 ± 20.63, P=0.004)

had a significantly higher mean sexual functioning score than patients who

had no history of sexual experiences and who had not been married (Table

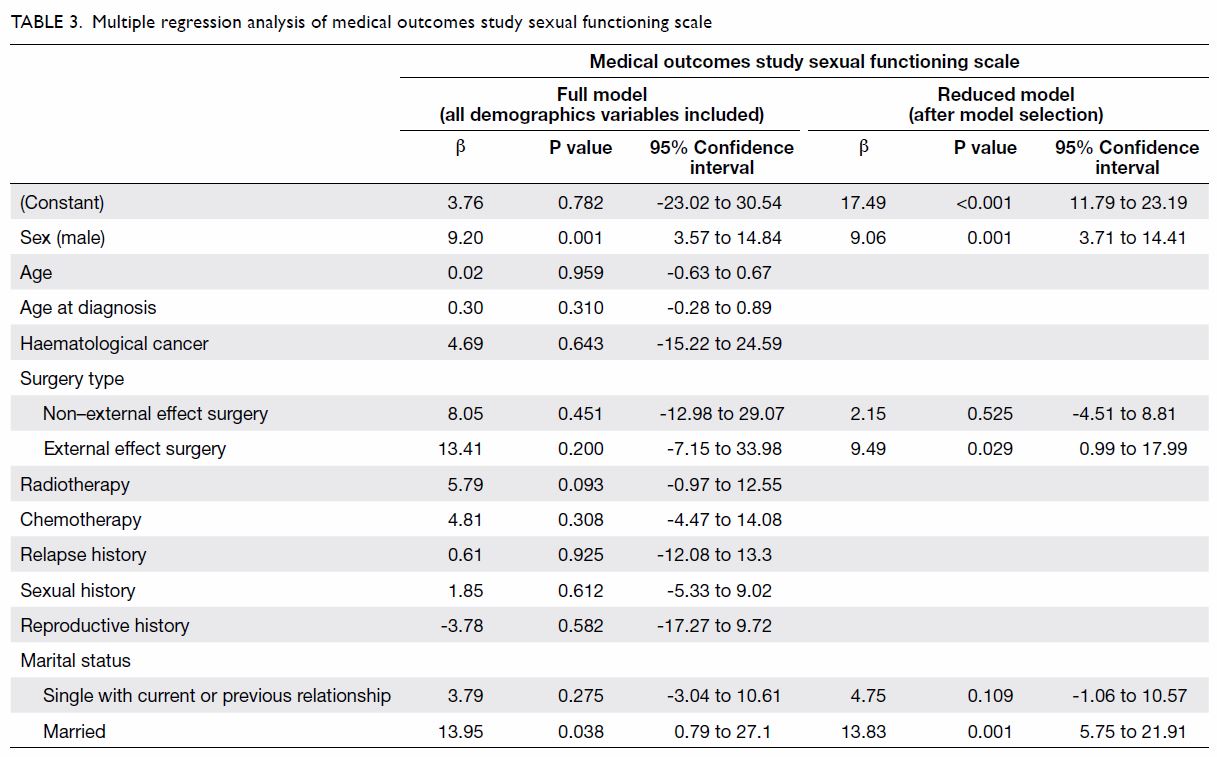

2). Multiple regression analysis controlling for all potential

confounders suggested that male sex (β=9.20, P=0.001) and marital status

of ‘married’ (β=13.95, P=0.038) were significantly associated with higher

sexual functioning score (ie, more sexual problems) [Table

3].

Assessments of self-esteem, body image, and depression

in all patients

The mean Rosenberg self-esteem scale score was 29.9

± 4.25. Multiple regression analysis showed that a history of relapse

(β=-2.89, P=0.044) was significantly associated with Rosenberg self-esteem

scale score following adjustment for other variables (ie, patients who had

a history of relapse had lower self-esteem) [online Supplementary Appendices 1 and 2].

The mean BIS score was 5.6 ± 4.45. Age at diagnosis

was statistically significantly positively correlated with BIS score (r=0.260,

P<0.001). Patients who had not undergone surgery (4.9 ± 4.09) had

significantly lower BIS score than patients who had undergone surgery (7.1

± 4.81, P=0.002). Patients who had a history of haematological cancer (4.9

± 4.11) also had significantly lower BIS score than patients who had a

history of non-haematological cancer (7.1 ± 4.77, P=0.002) [online

Supplementary Appendix 1]. Multiple regression analysis suggested

that age at diagnosis (β=0.22, P<0.001) was associated with BIS score (online Supplementary Appendix 2).

The mean PHQ score was 4.80 ± 4.27. The numbers of

patients who reported minimal depressive symptoms and major depression

were 68 (34%) and 24 (12%), respectively (online Supplementary Appendix 3). No statistical

significance was found across demographics variables (online

Supplementary Appendices 1 and 2).

The General Health Questionnaire Short Form-12

analysis revealed that the overall PCS was 51.2 ± 6.44. Age at the time of

this study (r=-0.159, P=0.025) and age at diagnosis (r=-0.170,

P=0.017) were significantly negatively correlated with PCS. Patients who

had undergone surgery without external effects (51.9 ± 5.20) had

significantly higher mean PCS (ie, better physical health) than patients

who had undergone surgery with external effects (47.5 ± 7.39, P=0.018) [online Supplementary Appendix 1]. Multiple

regression analysis showed that male sex (β=2.04, P=0.024) was

significantly associated with PCS, following adjustment for other

variables (online Supplementary Appendix 2). In contrast, the

overall MCS was 49.0 ± 9.00. There were no statistically significant

relationships between MCS and any demographic variables (online

Supplementary Appendices 1 and 2).

Subgroup analysis based on sexual functioning scores

Patients were divided into three groups based on

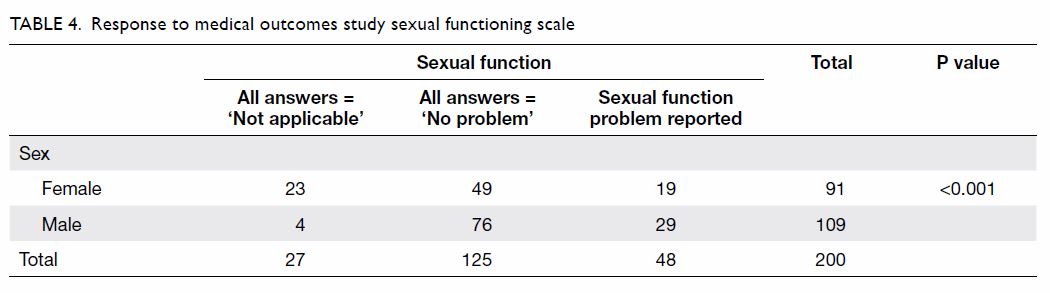

their sexual functioning scores. Forty-eight (24.0%) patients had

experienced at least one sexual problem, 125 (62.5%) patients reported

that they never had any sexual problem and/or stated ‘not applicable’, and

27 (13.5%) patients reported ‘not applicable’ for all items. Among women

in this study, 19 (20.9%) reported at least a small problem in at least

one aspect of sexual function, 49 (53.8%) reported ‘not a problem’ and/or

‘not applicable’ for all items, and 23 (25.3%) reported ‘not applicable’

for all items; among men in this study, these numbers were 29 (26.6%), 76

(69.7%), and four (3.7%), respectively (Table 4).

In the group with no sexual problems, more patients

had haematological cancers (n=89, 71.2% vs n=24, 50.0%; P=0.009), fewer

patients underwent surgery (n=34, 27.2% vs n=24, 50.0%; P=0.004), fewer

patients underwent surgery with external effects (n=9, 26.5% vs n=13,

54.2%; P=0.032), and fewer patients were regular social drinkers (n=2,

1.6% vs n=6, 12.5%; P=0.013). The group with no sexual problems also had

statistically significantly higher PCS (52.5 ± 5.62 vs 48.1 ± 7.96,

P=0.003), higher Rosenberg self-esteem scale score (30.6 ± 4.24 vs 28.4 ±

4.06, P=0.010), lower mean BIS score (4.9 ± 3.89 vs 7.5 ± 5.38, P=0.008),

and lower mean PHQ score (4.1 ± 4.44 vs. 6.8 ± 3.89, P=0.001) [Table

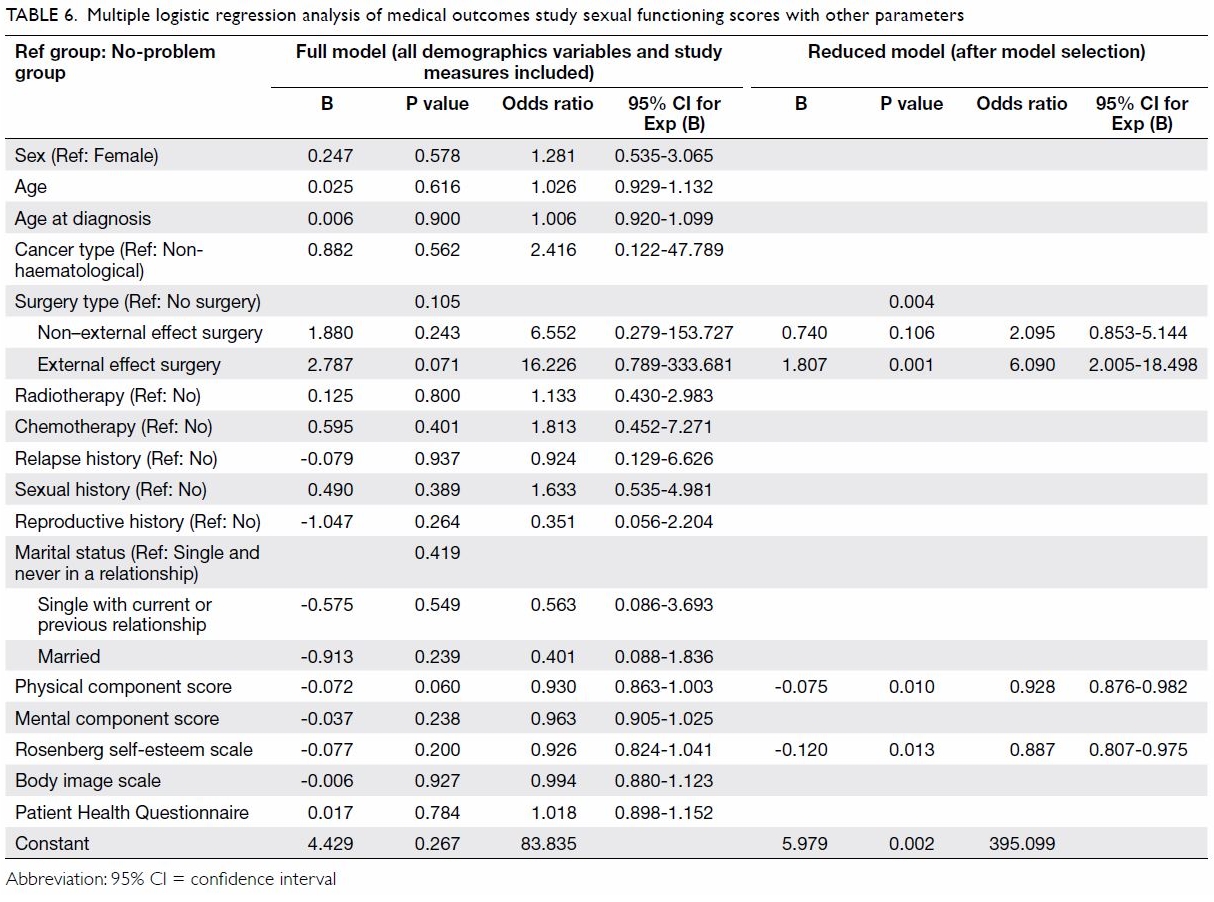

5]. However, in multivariable logistic regression analysis

controlling for all potential confounders, no variables were statistically

significant when comparing the group with no problems to the group with

problems. After model selection, a history of surgery with external

effects (odds ratio [OR]=6.09, P=0.001), PCS (OR=0.93, P=0.010), and

Rosenberg self-esteem scale score (OR=0.89, P=0.013) were significantly

related to the presence of sexual function problems (Table

6).

Table 5. Comparison between patients without sexual functioning problems (all responses to medical outcomes study sexual functioning scale = “no problem”) and those with reported sexual functioning problems (any sexual functioning problem reported on medical outcomes study sexual functioning scale)

Table 6. Multiple logistic regression analysis of medical outcomes study sexual functioning scores with other parameters

Discussion

Summary

In this study, approximately one-quarter of young

Chinese cancer survivors in Hong Kong reported at least one sexual

problem. Sexual problems were more common in men, in patients diagnosed

with cancer at an older age, and in patients who were married or had a

history of sexual experiences. Moreover, the presence of sexual problems

was significantly associated with a history of surgery, as well as a

history of surgery with external effects; patients with sexual problems

generally had lower physical well-being scores, lower self-esteem scores,

higher BIS scores, and an increased number of depressive symptoms. This

new information can aid in understanding our patients’ needs and in

guiding the provision of necessary care.

Sex-related differences in sexual function outcomes

In a similar study in the United States,4 involving 599 cancer survivors aged 18 to 39 years, 52%

of female and 32% of male respondents reported at least ‘a small problem’

in one or more areas of sexual functioning. Overall, 42.7% of the patients

in that study reported at least one problematic symptom; the overall

sexual functioning score (indicative of more problems) was higher in women

(21.6) than in men (10.6). Interestingly, the findings in our study

contrasted with those of the prior study. Approximately one-quarter of

survivors (24% overall, 26.6% of men, 20.9% of women) had at least one

sexual problem. Furthermore, the overall sexual functioning scores for

male and female survivors were 32.3 and 23.6, respectively. Therefore,

fewer cancer survivors may experience sexual problems in Hong Kong.

However, the problems experienced by these survivors may be more severe,

as reflected by the higher sexual functioning score.

In our study, men had higher sexual functioning

scores (ie, more sexual problems) than women. However, compared with men

in the study (3.7%), many more women (25.3%) reported ‘not applicable’

(P<0.001). An overall lower score among women may not necessarily mean

that they experienced fewer sexual problems; it might indicate that they

were less sexually active. By excluding responses of ‘not applicable’ from

the overall sexual functioning scale assessment, we found no significant

sex-related difference in sexual functioning score (P=0.499). The mean

scores for women and men were 31.62 ± 15.72 and 33.51 ± 19.25,

respectively. Regarding patients with responses of ‘not applicable’ in the

overall sexual functioning scale, 85.2% did not have sexual experience.

Furthermore, women in the present study may have been less sexually active

than men. A larger proportion of female survivors might only have sexual

intercourse after marriage and thus be unaware of sexual problems prior to

that point. Therefore, long-term assessment of sexual function is

important for identifying sexual problems in cancer survivors, especially

women.

Sex-related differences in specific sexual problems

Overall, the most common sexual problems reported

were difficulties in relaxing and enjoying sex (19.5%) and difficulties in

achieving an erection or orgasm (18.5%). Comparatively fewer survivors

reported lack of sexual interest (13.0%) and problems in becoming sexually

aroused (13.5%). Frederick et al16 performed a semi-structured interview

study in a paediatric oncology and survivorship clinic, involving 22

childhood cancer survivors aged 18 to 39 who reported two or more sexual

problems. The most commonly reported sexual problems were also

difficulties in relaxing and enjoying sex (n=19, 86%) and difficulties in

achieving an erection or orgasm (n=18, 82%), as in the present study.

Frederick et al16 also reported

that for each of the sexual function items, the proportion of women who

reported problems (34.1%-39.5%) was greater than the proportion of men who

reported problems (15.3%-20.4%). However, our study showed similar

proportions of women and men experiencing problems in becoming sexually

aroused (women: 13.2%, men: 13.8%) and in achieving an erection or orgasm

(women: 18.7%, men: 18.3%). A greater proportion of men reported a lack of

sexual interest (women: 8.8%, men: 16.5%) and an inability to relax or

enjoy sex (women: 17.6%, men: 21.1%). The sexual problems experienced by

cancer survivors seemed to differ between sexes. In Chinese culture, men

play a more dominant role in a relationship, and typically initiate sexual

activity.17 This might be why more

men reported problems regarding sexual desire, including sexual interest,

relaxation, and enjoyment. Because Asian women are more passive in terms

of sexual activity, they might not view reduced sexual interest as a

problem.18 Instead, they might be

more concerned with an inability to achieve orgasm during sex.

The authors of previous studies proposed that

greater numbers of female survivors reported sexual problems because they

were more likely to experience cancer-related physical changes and

psychological distress.4 19 However, our study showed no significant sex-related

differences in physical health (P=0.072), mental health (P=0.354),

self-esteem (P=0.184), body image (P=0.057), or depressive symptoms

(P=0.349). This implies that the cancer survivors in our study did not

experience sex-specific effects of their childhood cancer experience on

their quality of life.

Implications for patient treatment

It is well-known that treatments for cancer may

cause adverse effects on sexual function. Both Kenney et al20 and Van Dorp et al21

reviewed the literature regarding reproductive health of male and female

survivors. They noted that alkylating agent chemotherapy and gonadal

irradiation carried dose-related risks of primary gonadal dysfunction,

which affected both sexual function and fertility. Chow et al22 also stated that surgery might involve long-term

consequences, disfiguration with psychosocial impact, and delayed

complications. Our study found that a larger proportion of survivors who

had undergone surgery, especially surgery with external effects, reported

problems involving sexual function, whereas survivors who had undergone

radiation or chemotherapy showed no significant difference between the

proportions of survivors who reported the presence or absence of problems

involving sexual function.

Adolescence and young adulthood are the points in

life when people focus intensely on their own bodies and can experience

dissatisfaction with their bodies and physical appearances.23 Any alterations in physical appearance may affect

their self-perceptions. Indeed, in a study involving focus groups and

questionnaire surveys among survivors aged 15 to 29 years and matched

controls to investigate body image and sexual health among adolescents and

young adult cancer survivors, Olsson et al24

found that survivors perceived themselves to be less sexually attractive

due to scars on their bodies and were less satisfied with their sexual

function, compared with their matched controls.

With the progression of surgical techniques, such

as the introduction of minimally invasive surgery, we presume that the

impacts of scarring and physical disfiguration may be minimised. Until

this change occurs, healthcare professionals should provide information

regarding the potential adverse effects of treatments on the reproductive

system and sexual function, as well as counselling to the survivors;

importantly, survivors interviewed in previous studies indicated they had

unmet needs for information, support, and counselling.20

Limitations

There were some limitations in our study. Because

we did not include a control arm, we could not assess whether there were

any differences between our patients and similar age-matched young adults

in terms of the measured parameters. Therefore, we plan to perform a

follow-up study that involves the application of the assessments in these

questionnaires to similarly aged individuals in the general population to

confirm our findings. Another limitation of this study was that it was

performed in a single centre and the findings may be biased due to the

specific patient population involved. However, this is one of the main

children’s cancer centres in Hong Kong, and is therefore a major referral

centre that receives patients from various regions of Hong Kong; combined

with the moderate sample size, we consider this to provide a good

representation of adult survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong.

Conclusion

In this cross-sectional study of 200 young Chinese

cancer survivors, approximately one-quarter of the patients reported at

least one sexual problem. A history of sexual problems was significantly

associated with a history of surgery, as well as a history of surgery with

external effects. Compared with patients without sexual problems, those

with sexual problems generally had lower physical well-being scores, lower

self-esteem scores, higher body image distress scores, and an increased

number of depressive symptoms. Given the findings in this study, aspects

of life beyond disease condition and physical function should be

considered in adult survivors of childhood cancers. Moreover, appropriate

referral and intervention should be initiated for these patients when

necessary.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design: CF Ng, AWK Leung.

Acquisition of data: BSY Lau, CF Ng, AWK Leung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CYL Hong, BSY Lau, CF Ng.

Drafting of the article: CYL Hong, BSY Lau, CF Ng.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: BSY Lau, CF Ng, AWK Leung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CYL Hong, BSY Lau, CF Ng.

Drafting of the article: CYL Hong, BSY Lau, CF Ng.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

As editors of the journal, CF Ng and JYC Teoh were

not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have no conflicts

of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

The project was supported by Hong Kong Children

Cancer Fund.

Ethics approval

Approvals (CRE-2014.674) from The Joint Chinese

University of Hong Kong—New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research

Ethics Committee were obtained.

References

1. World Health Organization. Sexual

health—a new focus for WHO. Prog Reprod Health Res 2004;67:1-8.

2. Gan HW, Spoudeas HA. Long-term follow-up

of survivors of childhood cancer (SIGN Clinical Guideline 132). Arch Dis

Child Educ Pract Ed 2014;99:138-43. Crossref

3. Jacobs LA, Pucci DA. Adult survivors of

childhood cancer: the medical and psychosocial late effects of cancer

treatment and the impact on sexual and reproductive health. J Sex Med

2013;10 Suppl 1:120-6. Crossref

4. Zebrack BJ, Foley S, Wittmann D, Leonard

M. Sexual functioning in young adult survivors of childhood cancer.

Psychooncology 2010;19:814-22. Crossref

5. Sundberg KK, Lampic C, Arvidson J,

Helström L, Wettergren L. Sexual function and experience among long-term

survivors of childhood cancer. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:397-403. Crossref

6. Bober SL, Zhou ES, Chen B, Manley PE,

Kenney LB, Recklitis CJ. Sexual function in childhood cancer survivors: a

report from project REACH. J Sex Med 2013;10:2084-93. Crossref

7. Sherbourne C. Social functioning: sexual

problems measures. In: Stewart AL, Ware JE, editors. Measuring Functioning

and Well-being: the Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Durham (NC), United

States: Duke University Press; 1992: 194-204.

8. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A

12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary

tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220-33. Crossref

9. Lam CL, Tse EY, Gandek B. Is the

standard SF-12 health survey valid and equivalent for a Chinese

population? Qual Life Res 2005;14:539-47. Crossref

10. Rosenberg M. Society and the

Adolescent Self-image. Princeton [NJ], United States: Princeton University

Press; 1965.

11. Li HC, Chung OK, Ho KY, Chiu SY, Lopez

V. A descriptive study of the psychosocial well-being and quality of life

of childhood cancer survivors in Hong Kong. Cancer Nurs 2012;35:447-55. Crossref

12. Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, Al

Ghazal S. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer

2001;37:189-97. Crossref

13. Lin MS. An investigation on the body

image, medication adherence and quality of life in patients with systemic

lupus erythematosus after prednisolone treatment [thesis]. China Medical

University, Taichung City, Taiwan; 2010.

14. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB.

The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern

Med 2001;16:606-13. Crossref

15. Yu X, Tam WW, Wong PT, Lam TH, Stewart

SM. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms

among the general population in Hong Kong. Compr Psychiatry

2012;53:95-102. Crossref

16. Frederick NN, Recklitis CJ, Blackmon

JE, Bober S. Sexual dysfunction in young adult survivors of childhood

cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63:1622-8. Crossref

17. Lo SS, Kok WM. Sexual behavior and

symptoms among reproductive age Chinese women in Hong Kong. J Sex Med

2014;11:1749-56. Crossref

18. Atallah S, Johnson-Agbakwu C,

Rosenbaum T, et al. Ethical and sociocultural aspects of sexual function

and dysfunction in both sexes. J Sex Med 2016;13:591-606. Crossref

19. The Family Planning Association of

Hong Kong. Report on youth sexuality study 2016. 2017. Available from:

https://www.famplan.org.hk/en/media-centre/press-releases/detail/fpahk-report-on-youth-sexuality-study.

Accessed 9 Jul 2018.

20. Kenney LB, Antal Z, Ginsberg JP, et

al. Improving male reproductive health after childhood, adolescent, and

young adult cancer: progress and future directions for survivorship

research. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2160-8. Crossref

21. van Dorp W, Haupt R, Anderson RA, et

al. Reproductive function and outcomes in female survivors of childhood,

adolescent, and young adult cancer: a review. J Clin Oncol

2018;36:2169-80. Crossref

22. Chow EJ, Antal Z, Constine LS, et al.

New agents, emerging late effects, and the development of precision

survivorship. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2231-40. Crossref

23. Cash T. Encyclopedia of Body Image and

Human Appearance. Oxford, United Kingdom: Elsevier Science; 2012.

24. Olsson M. Adolescent and Young Adult

Cancer Survivors— Body Image and Sexual Health. Gothenburg, Sweden:

University of Gothenburg; 2018.