Hong Kong Med J 2014 Dec;20(6):556.e1–3

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134106

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Pneumonitis and extreme failure to thrive

KL Hon, MD, FCCM1; TF Leung, FRCPCH, FHKAM (Paediatrics)1; YS Yau, MRCP (UK), FHKAM (Paediatrics)2

1 Department of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Paediatrics, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof KL Hon (ehon@cuhk.edu.hk)

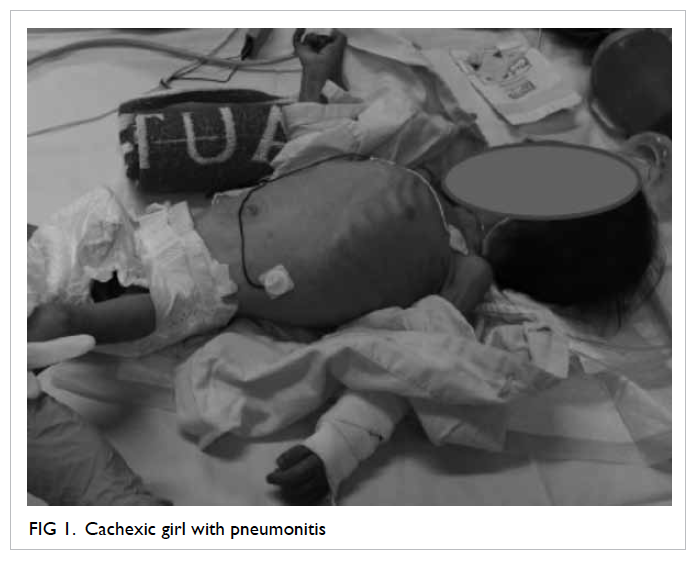

Failure to thrive is an uncommon, challenging,

but important basket of differential diagnoses to

manage in the city of Hong Kong. Diagnosis may

be non-organic or functional. During outbreaks

of avian influenza in Mainland China and MERS/SARI (Middle East respiratory syndrome/severe

acute respiratory illness) coronavirus infection in

the Middle East in early 2013,1 a 27-month-old girl

was brought by her parents to Hong Kong following

a long period of hospitalisation and investigations in

Mainland China for recurrent pneumonia, chronic

diarrhoea, lymphadenopathy, oral candidiasis, and

failure to thrive. Reportedly, no bacterial or viral

pathogens had been found. Antenatal anti–human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody testing was

negative in the mother. There had been no adverse

reaction to Bacille Calmette-Guérin and routine

immunisations. The child had been exclusively

breastfed and her growth and development were

normal until 9 months of age. The child was admitted

to the paediatric intensive care unit (ICU) of a Hong

Kong hospital for management. She was noted to have

profound failure to thrive with a body weight of only

5 kg (Fig 1). Chest X-ray showed diffuse pneumonitis (Fig 2). She required oxygen supplementation but mechanical ventilation was not needed.

Which of the following investigations will most

likely give the underlying diagnosis?

1. White cell counts and differentials for

congenital neutrophil abnormality

2. Complement C3 and C4 levels for congenital

complement deficits

3. Immunoglobulin A for immunoglobinopathy

4. H7N9, coronavirus, mycoplasma, and

chlamydia serology for atypical pneumonia

5. HIV testing

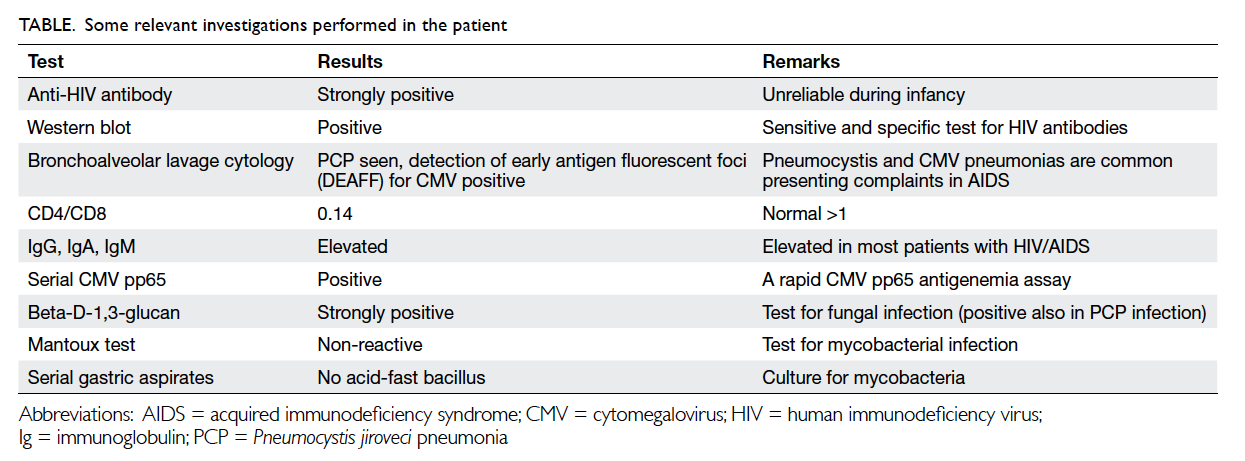

After performing various investigations

(Table), the child tested positive for HIV infection,

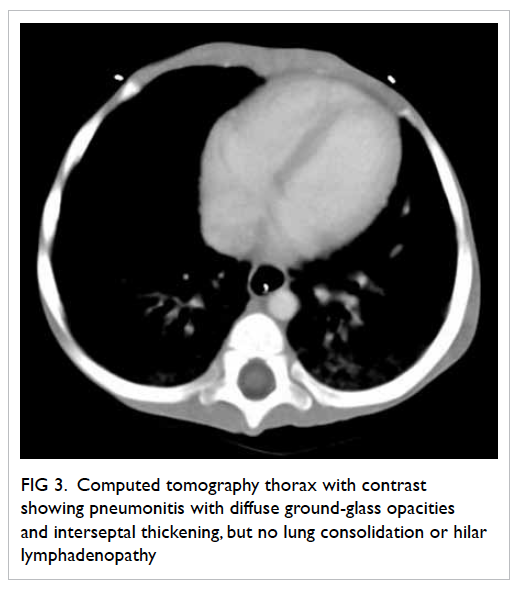

confirming that she had acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Computed tomographic

scan of thorax showed pneumonitis (Fig 3).

Treatment for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

and cytomegalovirus infection was commenced.

Following stabilisation, the child was referred

to a paediatric infectious disease specialist for

continuation of care. Highly active antiretroviral

therapy was started when opportunistic infections

were under control. The child was last seen in June

2014; she was asymptomatic and had been thriving

well.

Figure 3. Computed tomography thorax with contrast showing pneumonitis with diffuse ground-glass opacities and interseptal thickening, but no lung consolidation or hilar lymphadenopathy

The parents refused HIV testing but reported

that the child had received blood products after onset

of illness while in the Mainland hospital. Both were

subsequently confirmed HIV positive. Nevertheless,

HIV was most likely to be vertically (mother to child)

transmitted.2 3 4 5 In many areas of the world, HIV/AIDS

has become a chronic rather than an acutely fatal

disease.3 Half of the infants born with HIV die before

2 years of age without treatment.2 3 4 5

Pneumonitis is usually caused by viruses or

atypical pathogens. Since the atypical pneumonitis

epidemic of coronavirus in 2003, Hong Kong and

the rest of the world have heightened surveillance

for outbreaks of atypical pneumonitis with novel

pathogens such as avian or swine influenza, or

coronavirus.1 In the cosmopolitan city of Hong Kong,

paediatric HIV remains a relatively rare diagnosis.

Nevertheless, due to the busy trafficking between

Hong Kong and Mainland China, paediatricians in

Hong Kong must be vigilant of such possibility in

Hong Kong children of Mainland parents. Despite

the misleading history by the parents about negative

screening for HIV, paediatricians at the paediatric

ICU were prompt to arrive at the definitive diagnosis

by requesting HIV testing and considering HIV

infection as a possibility to explain the combination

of pneumonitis and extreme failure to thrive in this

child.

This case is interesting and highlights the

importance of excluding HIV infection in a child with

dual symptoms of recurrent infections and failure to

thrive, even when the mother had tested negative

for HIV antibodies initially; the test may have been

performed in a window period during pregnancy.

Differential diagnoses for failure to thrive

include child abuse and neglect, cystic fibrosis (rare in

Hong Kong), gastroesophageal reflux, growth failure,

growth hormone deficiency, and HIV infection.6 7

The history and physical examination should guide

any laboratory or ancillary testing. Most infants and

children with growth failure related to environmental

factors need very limited laboratory screenings.

This child presented with recurrent infections

and candidiasis. Approach to recurrent infections

resulting in failure to thrive may include HIV testing,

sweat test for cystic fibrosis (if history is relevant),

metabolic and endocrinology screening, tuberculosis

testing, and stool studies.

Basing on disease onset, this is most likely a

case of vertical transmission of HIV. In infants, the

onset of AIDS symptoms can take a few months; in

contrast, it can be many years before adults develop

symptoms of HIV. Thus, repeated HIV testing is very

important to initiate timely treatment in the parents.

References

1. Hon KL. Severe respiratory syndromes: travel history

matters. Travel Med Infect Dis 2013;11:285-7. CrossRef

2. Sepkowitz KA. AIDS—the first 20 years. N Engl J Med

2001;344:1764-72. CrossRef

3. Knoll B, Lassmann B, Temesgen Z. Current status of HIV

infection: a review for non–HIV-treating physicians. Int J

Dermatol 2007;46:1219-28. CrossRef

4. Coutsoudis A, Kwaan L, Thomson M. Prevention of

vertical transmission of HIV-1 in resource-limited

settings. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2010;8:1163-75. CrossRef

5. Thorne C, Newell ML. HIV. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med

2007;12:174-81. CrossRef

6. Nangia S, Tiwari S. Failure to thrive. Indian J Pediatr

2013;80:585-9. CrossRef

7. Hendaus M, Al-Hammadi A. Failure to thrive in infants

(review). Georgian Med News 2013;(214):48-54.