Hong Kong Med J 2023 Oct;29(5):412–20 | Epub 5 Oct 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Telemedicine acceptance by older adults in Hong Kong during a hypothetical severe outbreak and after the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional cohort survey

Maxwell CY Choi1; SH Chu, MB, ChB1; LL Siu1; Anakin Gajy Tse, MB, ChB1; Justin CY Wu, MD, FRCP2,3; H Fung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Community Medicine)3,4; Billy CF Chiu, MB, BS, MPH3; Vincent CT Mok, MD, FRCP5

1 Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 CUHK Medical Centre, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Vincent CT Mok (vctmok@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Telemedicine services worldwide

have experienced unprecedented growth since

the early days of the coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) pandemic. Multiple studies have

shown that telemedicine is an effective alternative

to conventional in-person patient care. This study

explored the public perception of telemedicine in

Hong Kong, specifically among older adults who are

most vulnerable to COVID-19.

Methods: Medical students from The Chinese

University of Hong Kong conducted in-person

surveys of older adults aged ≥60 years. Each survey

collected socio-demographic information, medical

history, and concerns regarding telemedicine use.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression

analyses were conducted to identify statistically

significant associations. The primary outcomes were

acceptance of telemedicine use during a hypothetical

severe outbreak and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results: There were 109 survey respondents.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed

that the expectation of government subsidies for

telemedicine services was the strongest common

driver and the only positive independent predictor

of telemedicine use during a hypothetical severe

outbreak (P=0.016) and after the COVID-19

pandemic (P=0.003). No negative independent

predictors of telemedicine use during a hypothetical

severe outbreak were identified. Negative

independent predictors of telemedicine use after

the COVID-19 pandemic included older age and residence in the New Territories (both P=0.001).

Conclusions: Government support, such as

telemedicine-specific subsidies, will be important for

efforts to promote telemedicine use in Hong Kong

during future severe outbreaks and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Robust dissemination of information

regarding the advantages and disadvantages of

telemedicine for the public, especially older adults,

is needed.

New knowledge added by this study

- Older age and residence in the New Territories were negative predictors of telemedicine use during a hypothetical severe outbreak and after the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

- The expectation of government support (eg, subsidies) is a positive predictor of telemedicine use during a hypothetical severe outbreak and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Telemedicine carries minimal risk of disease transmission and may serve as a powerful addition to conventional in-person consultation, but it will not completely replace conventional consultation methods.

- Government support, such as telemedicine-specific subsidies and public education, will help encourage telemedicine use in Hong Kong.

Introduction

In 2020, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

pandemic caused many healthcare services

worldwide to experience a decline in patient

numbers because of cancellations related to a fear of

disease transmission.1 This decline led to increasing

interest in the expansion of telemedicine services

(ie, the practice of medicine over a distance through

telecommunication systems2) as a potential solution

to address gaps in healthcare delivery and minimise

the risk of COVID-19 transmission.3

Despite the availability of numerous virtual

technological solutions, Hong Kong has not

experienced significant progress towards the

widespread implementation and promotion of

telemedicine.4 Therefore, exploration of the factors

contributing to the relative underutilisation of

telemedicine by older adults in Hong Kong will

help to identify current limitations of the healthcare

system, while facilitating future implementation of

telemedicine.

The primary objectives of this study were

to examine the main concerns that older adults

have towards telemedicine and then evaluate

telemedicine use in two hypothetical scenarios:

during a severe outbreak while under lockdown, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study,

‘severe outbreak’ was defined as a sudden increase in

disease frequency within a limited geographic area,

which requires public health interventions (eg, a

government-imposed lockdown involving temporary

restrictions on travel and social interactions, along

with quarantine measures)5; ‘after the COVID-19

pandemic’ was defined as the expected new norm

(ie, endemic COVID-19 requiring regular vaccines,

with societal adaptation to seasonal deaths and

complications in the absence of lockdowns, masks,

or social distancing).6

This study specifically explored perception of

telemedicine among older adults because they have

the highest risk of severe COVID-197 8 and may

experience the greatest benefit from telemedicine

use.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study consisted of an online survey completed

by a cohort of older adults in Hong Kong. The survey

was conducted from 8 October to 15 November

2020, between the third and fourth waves of

COVID-19 in the city.9 10 Medical student volunteers

from The Chinese University of Hong Kong were

recruited to facilitate data collection from older

adults in their families. Considering the overall need

for social distancing, we assumed that random in-person

visits to older adults carried a high risk of

disease transmission.11 Therefore, we chose to survey

close relatives of medical students living in the same

household; this approach was expected to reduce the

risk of disease transmission among medical students

and participants.11

In total, 59 medical student volunteers

were recruited in September 2020. To ensure

standardisation of the survey protocol, a mandatory

virtual training course was conducted via Zoom

on 28 September 2020, which included a detailed

written survey guide to help the volunteers to

facilitate the survey.

This study adhered to the STROBE

(Strengthening the Reporting of Observational

Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.

Procedures

The survey targeted older adults (aged ≥60 years) in

Hong Kong. The closest caretakers were allowed to

complete the survey on behalf of older adults who

had health-related difficulty expressing themselves.12

This completion-by-proxy approach was used

because such caretakers regularly accompany older

adults to medical appointments and are likely to

have a good overall understanding of those older

adults’ healthcare needs. The survey was completed and submitted online; consent was obtained from

each participant before the start of the survey, and all

surveys were facilitated by trained medical student

volunteers.

The survey consisted of multiple-choice

questions that addressed five factors with important

effects on the perception of telemedicine among

older adults: (1) socio-demographic characteristics,

including age, gender, education level, number of

cohabitants in the same household, employment

status, and residential area; (2) medical history,

including types of chronic illnesses, frequency and

difficulty of visiting regular doctors in public and

private sectors, numbers and types of prescribed

medications, and private health insurance enrolment

status; (3) domestic support for telemedicine use,

including digital device availability and internet

access; (4) acceptance of telemedicine use in

two scenarios (ie, during a hypothetical severe

outbreak and after the COVID-19 pandemic); and

(5) telemedicine-associated values, concerns, and

expectations (eg, concerns about effectiveness and

satisfaction). With respect to the acceptance of

telemedicine use in two scenarios, respondents were

informed that telemedicine is mainly used during

follow-up for chronic medical conditions or when

visiting a doctor who is familiar with the patient

and their medical history; it is rarely used to visit

an unfamiliar doctor for a new or acute medical

condition.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS (Windows

version 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United

States). The cohort survey responses were first

thematically classified into four main categories,

namely demographics, home characteristics, medical

history, and telemedicine-related factors. The two

main primary outcome variables in our study were

dichotomous variables concerning acceptance of

telemedicine use: during a hypothetical severe

outbreak and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Univariate logistic regression analysis was

conducted to identify predictors of telemedicine

use during a hypothetical severe outbreak and after

the COVID-19 pandemic, respectively. Multivariate

logistic regression analysis was performed using

variables that were statistically significant in

univariate analysis. To avoid variable overfitting, for

acceptance of telemedicine use during a hypothetical

severe outbreak, only variables with P values <0.05

in univariate analysis were included in multivariate

analysis; for acceptance of telemedicine use after

the pandemic, only variables with P values <0.01

in univariate analysis were included in multivariate

analysis. Continuous data were reported as mean ±

standard deviation.

Results

Cohort characteristics

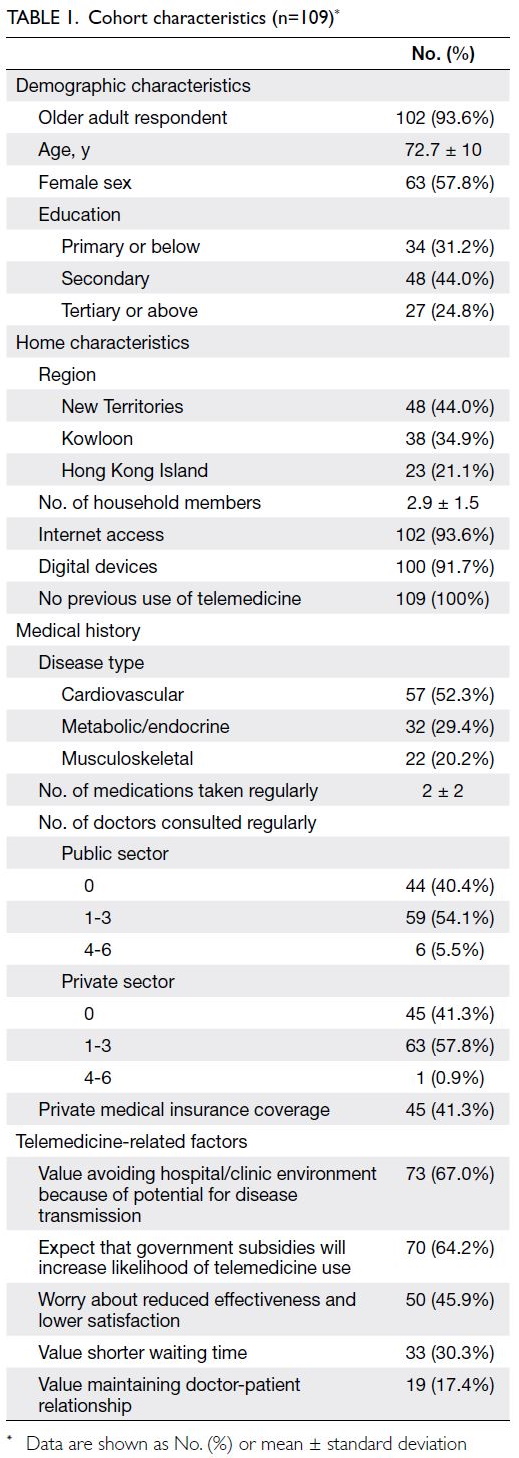

Of the 109 respondents surveyed by 59 medical

student volunteers, 93.6% were older adults, whereas

6.4% were caretakers who completed the survey on

behalf of an older adult they cared for. The detailed

characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 1.

The mean respondent age was 72.7 ± 10 years; most

respondents were women (57.8%) and had at least

completed secondary education (68.8%). In terms of

household characteristics, 44.0% of the respondents

lived in the New Territories and the mean size of each

household was 2.9 ± 1.5 members. Although most

respondents had access to both the internet (93.6%)

and digital devices (91.7%), none had previously

used telemedicine; thus, they were unable to indicate

which type of telemedicine they would prefer.

The survey also collected detailed information

about the respondents’ medical histories. In

terms of disease epidemiology, the most common

chronic disease types were cardiovascular (52.3%),

metabolic/endocrine (29.4%), and musculoskeletal

(20.2%); the mean number of medications taken

was 2 ± 2. Most respondents regularly consulted

one to three doctors in both the public (54.1%) and

private sectors (57.8%), but fewer than half of the

respondents had private medical insurance coverage

(41.3%). In terms of telemedicine, most respondents

valued avoiding hospital or clinic environments

because of the potential for disease transmission

(67.0%); they also expected that government

subsidies13 would increase their likelihood of using

telemedicine (64.2%).

Furthermore, nearly half of the respondents

worried that telemedicine use would lead to

reduced effectiveness and lower satisfaction (45.9%);

however, fewer than half of the respondents valued

maintaining the doctor-patient relationship (17.4%)

or reducing waiting time (30.3%).

Stratification of survey data according to

acceptance of telemedicine use revealed that 89

respondents (81.7%) would accept telemedicine

during a hypothetical severe outbreak; after the

COVID-19 pandemic, 43 respondents (39.4%)

would accept telemedicine. The characteristics

of respondents who would and would not accept

telemedicine during a hypothetical severe outbreak

and after the pandemic are presented in the online supplementary Appendix.

Factors affecting telemedicine use during a

hypothetical severe outbreak

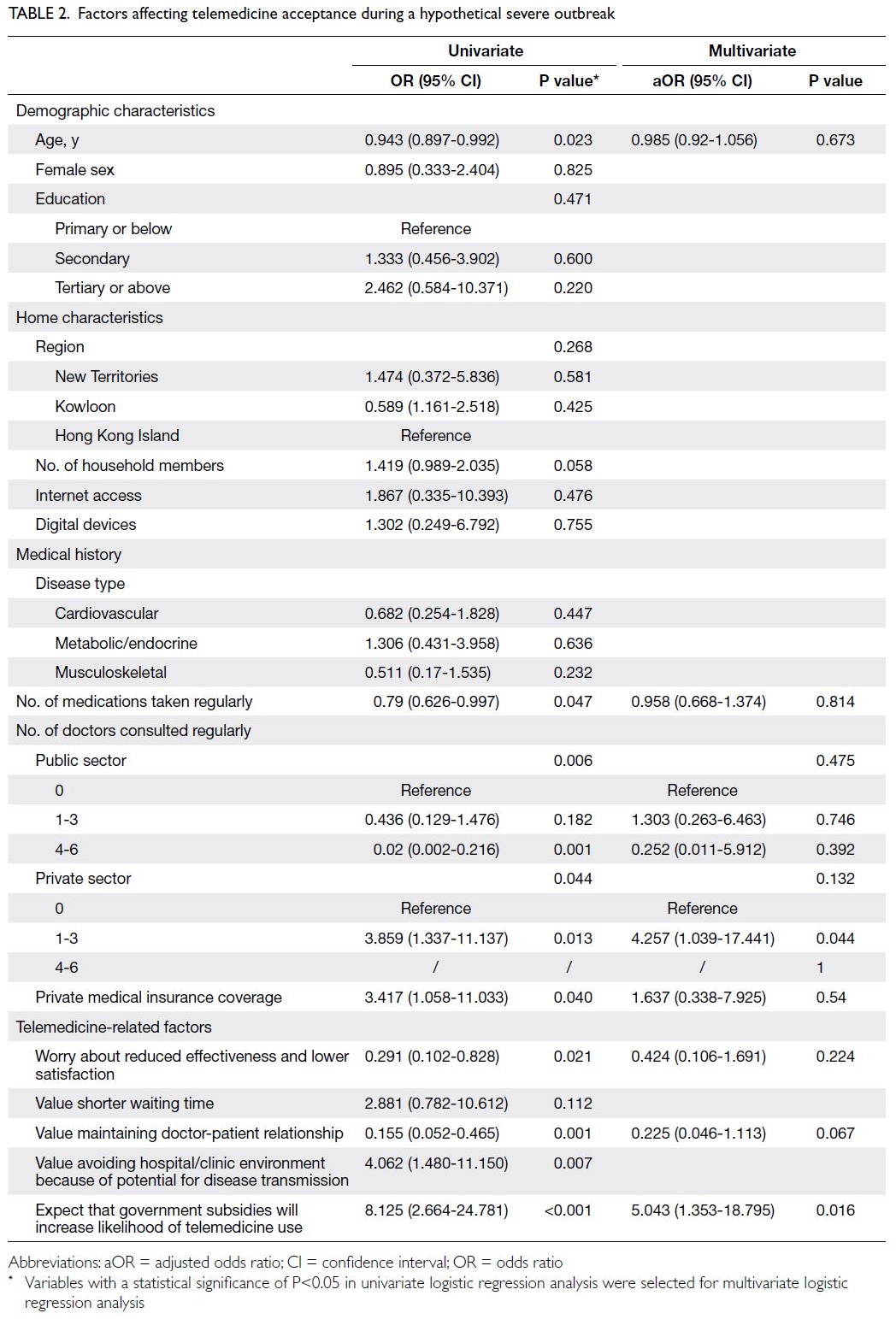

Multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 2)

showed that the expectation of government subsidies

for telemedicine services was the only positive

independent predictor of telemedicine use during a hypothetical severe outbreak (adjusted odds ratio

[aOR]=5.043, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.353-18.795; P=0.016). No negative independent predictors of telemedicine use during a hypothetical severe outbreak were identified.

Factors affecting telemedicine use after the

coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic

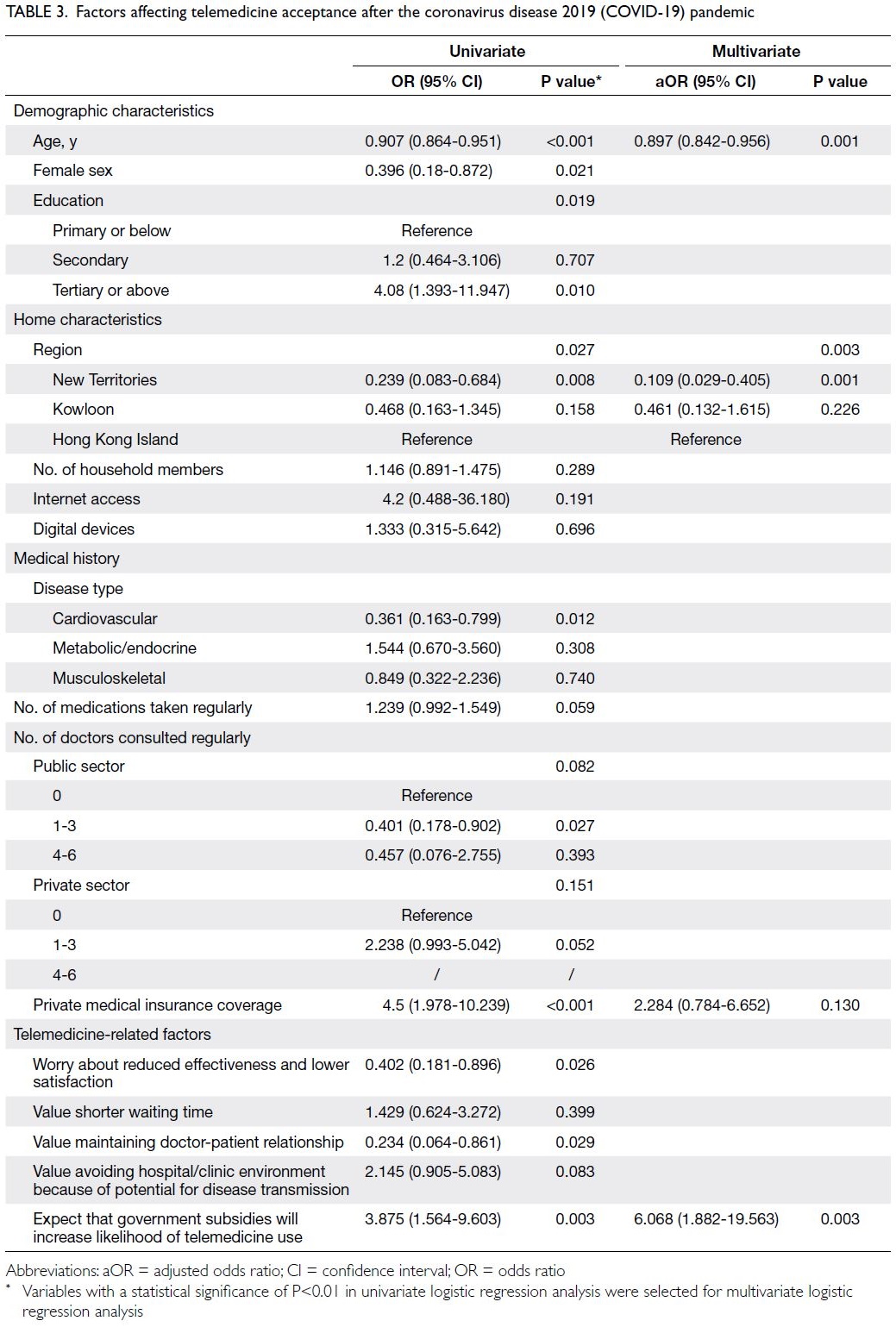

Multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3)

showed that the expectation of government subsidies

for telemedicine services was the strongest common

driver and the only positive independent predictor

of telemedicine use after the pandemic (aOR=6.068,

95% CI=1.882-19.563; P=0.003). However, there were

two negative independent predictors of telemedicine

use after the pandemic: older age (aOR=0.897,

95% CI=0.842-0.956; P=0.001) and residence in the

New Territories rather than on Hong Kong Island

(aOR=0.109, 95% CI=0.029-0.405; P=0.001).

Discussion

Interpretation of results

In this study, multivariate logistic regression analysis

revealed no negative independent predictors of

reduced telemedicine use during a hypothetical

severe outbreak. This result may be explained by the

fear of COVID-19 within the Hong Kong population,

which has prompted citizens to avoid public

transport and practise social distancing.14 Because

many Hong Kong citizens experienced the severe

acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in March 2003,

they remain fearful of unknown infectious diseases.15

Considering that telemedicine carries minimal risk

of disease transmission compared with conventional

in-person consultation,16 it is clearly valuable in

epidemic and pandemic scenarios; however, studies

thus far have shown that telemedicine is less effective

than hands-on procedures (eg, physical examination

or postoperative care).17 Nonetheless, rapid

technological advancements may soon overcome

these limitations. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer

that the characteristics and benefits of telemedicine

outweigh its limitations during severe outbreaks,

including epidemic and pandemic scenarios.

In both ‘severe outbreak’ and ‘after COVID-19

pandemic’ scenarios, the expectation of government

subsidies for telemedicine services was the strongest

common driver of telemedicine use; it was also the

only statistically significant positive independent

predictor of telemedicine use after the COVID-19

pandemic. For example, the Elderly Health Care

Voucher Scheme launched in Hong Kong in 2009

was intended to provide financial incentives for older

adults to seek healthcare services in the private sector,

thereby alleviating strain within the public healthcare

system. Thus far, this scheme has contributed

to positive uptake of telemedicine in the private

sector.13 Therefore, to encourage use of telemedicine

services during the pandemic, we propose extending

telemedicine-specific subsidies to older adults.

Furthermore, the role of government support

in promoting telemedicine use should be emphasised

and expanded. For example, Hong Kong’s older

adults could receive subsidies to purchase essential

digital devices for telemedicine consultations, such

as webcams and remote monitoring devices. Indeed,

a study in Australia showed that government support

for healthcare, such as the reduction of insurance

reimbursement restrictions, has been a key factor

in the country’s increased use of telemedicine.18

Moreover, public education regarding telemedicine

and digital health overall should be conducted

to address patient misconceptions and clarify

expectations regarding telemedicine. It is important

to emphasise that the use of telemedicine does

not imply that patients should discontinue follow-up.

Further education concerning the format (eg,

video calls and use of digital health applications),

effectiveness (ie, limited physical examination),

and other aspects of telemedicine is strongly

recommended because these were the most

important concerns among the respondents in the

current study.

There were two statistically significant negative

independent predictors of telemedicine use after

the COVID-19 pandemic: older age and residence

in the New Territories. For older adults, a lack of

technological competency is an important challenge

when adapting to a new mode of consultation. Older

adults often struggle with unfamiliar technology,

which may ultimately prevent many of them

from using telemedicine. To help older adults

adopt new technologies, telemedicine systems

should be designed with the goal of maximum

user-friendliness.19 For example, easy-to-navigate

interfaces and simple instructions with larger display

fonts may help increase older adults’ willingness to

use telemedicine for chronic illness follow-up after

the COVID-19 pandemic.

With respect to older adults who live in the

New Territories, a relatively more rural part of

Hong Kong, the digital infrastructure necessary to

provide telemedicine services may be less robust

than the infrastructure on Hong Kong Island and in

Kowloon. Indeed, the New Territories has the largest

number of high-poverty areas in Hong Kong, which

may be associated with low socio-economic status

and limited education leading to lower healthcare

utilisation.20 Poverty also has an effect on hospital

access, such that the New Territories generally

displays the least hospital access among all regions

of Hong Kong; however, considering the long travel

distances to hospitals and clinics, telemedicine

may be very beneficial for residents in this region.20

Overall, telemedicine accessibility in Hong Kong

remains a major concern that requires further

investigation.

Strengths

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Hong

Kong to comprehensively examine concerns about

telemedicine implementation among older adults,

both during a hypothetical severe outbreak and after

the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of telemedicine as

a novel approach to patient consultations may serve

as an important component of an effective geriatric

healthcare system during the pandemic and could

even be implemented as a powerful addition to in-person

consultation during clinical practice after the

pandemic.21

Additionally, the mandatory training course for

medical student volunteers and detailed explanation

of each question ensured adequate quality control, as

well as a full understanding of telemedicine, during

the completion of each survey. The training course

also ensured uniformity during survey delivery,

thereby minimising the potential for confirmation or

observer bias that could arise from unstandardised

survey delivery styles among different volunteers. A

survey guide was explicitly introduced in the training

course; it included a detailed rationale of the study

as well as key points to consider with each survey

question.

Limitations

Because the survey only included the responses of

family members of medical students, selection and

inter-observer biases were possible. However, these

biases were counterbalanced by the comprehensive

training course to achieve uniformity during survey

delivery. Retrospective analysis of the study results

did not suggest that the respondents favoured

telemedicine; thus, we concluded that the potential

for selection bias was negligible.

This study also had a relatively small sample size

because of pandemic-associated social distancing

restrictions. For example, the cohort did not involve

citizens residing on the outlying islands of Hong

Kong. These areas, with their remote locations and

limited hospital access,20 may have a greater need

for telemedicine. Therefore, caution is needed when

generalising our findings to populations outside of

Hong Kong. Furthermore, this study was performed

before the formal introduction of a COVID-19

vaccination programme, which has been shown to

greatly influence the attitude of the general public

towards health-seeking behaviours.22 Therefore, this

study may not be fully representative of the current

pandemic situation in Hong Kong.

Future studies

This study primarily focused on older adults.

Future studies should investigate the acceptance of

telemedicine among younger adults (aged <60 years), adolescents, and children. Future studies could also

compare the perspectives of caretakers and older

adults themselves on a larger scale to determine

whether concerns differ among stakeholders.

Conclusion

This study examined concerns among older adults

regarding the use of telemedicine, both during a

hypothetical severe outbreak while under lockdown,

and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings

indicated that government support was a key driver

of telemedicine use in Hong Kong under both

scenarios. After the pandemic, telemedicine-specific

subsidies and public education will be essential for

efforts to overcome telemedicine hesitancy that

arises from technological inconveniences related to

age and geographic location.

In the future, government support via

telemedicine-specific subsidies will be a key driver of

telemedicine use in Hong Kong, both during a severe

outbreak and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The

continued use of telemedicine after the pandemic

requires telemedicine systems that are designed

to ensure maximal age-friendliness. However,

telemedicine should be used in combination with

conventional in-person consultation rather than as

a replacement for such consultation.

Author contributions

Concept or design: JCY Wu, H Fung, BCF Chiu, VCT Mok.

Acquisition of data: MCY Choi, SH Chu, LL Siu, AG Tse.

Analysis or interpretation of data: MCY Choi, SH Chu, LL Siu, AG Tse.

Drafting of the manuscript: MCY Choi, SH Chu, LL Siu, AG Tse, VCT Mok.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: MCY Choi.

Acquisition of data: MCY Choi, SH Chu, LL Siu, AG Tse.

Analysis or interpretation of data: MCY Choi, SH Chu, LL Siu, AG Tse.

Drafting of the manuscript: MCY Choi, SH Chu, LL Siu, AG Tse, VCT Mok.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: MCY Choi.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Mr Brian Yiu from the Division of

Neurology, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The

Chinese University of Hong Kong for aid with statistical

analysis. The authors also thank all medical student volunteers

from The Chinese University of Hong Kong for assisting with

in-person surveys.

Declaration

This work was posted on medRxiv as a registered online preprint (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.15.21260346v1).

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study protocol was obtained from

the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories

East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ref No.:

2020.536). This research was performed in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and consent was obtained from

each participant before the start of the survey.

References

1. Wong SY, Zhang D, Sit RW, et al. Impact of COVID-19

on loneliness, mental health, and health service

utilisation: a prospective cohort study of older adults

with multimorbidity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract

2020;70:e817-24. Crossref

2. World Medical Association. WMA statement on the

ethics of telemedicine. 2018. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-statement-on-the-ethics-of-telemedicine/. Accessed 6 Apr 2021.

3. Lau C. Telemedicine in the time of COVID-19 and beyond.

MIMS Respirology. 2020. Available from: https://specialty.mims.com/topic/telemedicine-in-the-time-of-covid-19-and-beyond. Accessed 16 Jun 2021.

4. Legislative Council, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Development of telehealth services. ISE14/20-21. 2020.

Available from: https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/

english/essentials-2021ise14-development-of-telehealth-services.htm. Accessed 6 Apr 2021.

5. Reintjes R, Zanuzdana A. Outbreak investigations. In: Krämer A, Kretzschmar M, Krickeberg K, editors. Modern Infectious Disease Epidemiology. New York: Springer; 2010: 159-76. Crossref

6. Phillips N. The coronavirus is here to stay—here’s what that

means. Nature 2021;590:382-4. Crossref

7. Mok VC, Pendlebury S, Wong A, et al. Tackling challenges

in care of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias amid the

COVID-19 pandemic, now and in the future. Alzheimers

Dement 2020;16:1571-81. Crossref

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States

Government. COVID-19 risks and information for older

adults. 2023. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/covid19/index.html#:~:text=Older%20adults%20are%20more%20likely,very%20sick%20from%20COVID%2D19 .

Accessed 25 Sep 2023.

9. Wong MC, Wong EL, Huang J, et al. Acceptance of the

COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model:

a population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine

2021;39:1148-56. Crossref

10. Chan WM, Ip JD, Chu AW, et al. Phylogenomic analysis

of COVID-19 summer and winter outbreaks in Hong

Kong: an observational study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac

2021;10:100130. Crossref

11. Chauhan V, Galwankar S, Arquilla B, et al. Novel

coronavirus (COVID-19): leveraging telemedicine to

optimize care while minimizing exposures and viral

transmission. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2020;13:20-4. Crossref

12. Reinhard SC, Given B, Petlick NH, Bemis A. Supporting

family caregivers in providing care. In: Hughes RG, editor.

Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008: 341-404.

13. Yam CH, Wong EL, Fung VL, Griffiths SM, Yeoh EK. What

is the long term impact of voucher scheme on primary

care? Findings from a repeated cross sectional study

using propensity score matching. BMC Health Serv Res

2019;19:875. Crossref

14. Sit SM, Lam TH, Lai AY, Wong BY, Wang MP, Ho SY. Fear

of COVID-19 and its associations with perceived personal

and family benefits and harms in Hong Kong. Transl Behav

Med 2021;11:793-801. Crossref

15. Choi EP, Hui BP, Wan EY. Depression and anxiety in Hong

Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health

2020;17:3740. Crossref

16. Kadir MA. Role of telemedicine in healthcare during

COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Telehealth

Med 2020;5:1-5. Crossref

17. Williams AM, Bhatti UF, Alam HB, Nikolian VC. The role

of telemedicine in postoperative care. Mhealth 2018;4:11. Crossref

18. Thomas EE, Haydon HM, Mehrotra A, et al. Building on

the momentum: sustaining telehealth beyond COVID-19. J

Telemed Telecare 2022;28:301-8. Crossref

19. Narasimha S, Madathil KC, Agnisarman S, et al. Designing

telemedicine systems for geriatric patients: a review of the

usability studies. Telemed J E Health 2017;23:459-72. Crossref

20. Guo Y, Chang SS, Sha F, Yip PS. Poverty concentration

in an affluent city: geographic variation and correlates

of neighborhood poverty rates in Hong Kong. PLoS One

2018;13:e0190566. Crossref

21. Grossman Z, Chodick G, Reingold SM, Chapnick G,

Ashkenazi S. The future of telemedicine visits after

COVID-19: perceptions of primary care pediatricians. Isr J

Health Policy Res 2020;9:53. Crossref

22. Wang K, Wong EL, Ho KF, et al. Change of willingness to

accept COVID-19 vaccine and reasons of vaccine hesitancy

of working people at different waves of local epidemic

in Hong Kong, China: repeated cross-sectional surveys.

Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:62. Crossref