Hong Kong Med J 2023 Dec;29(6):498–505 | Epub 20 Nov 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Cross-sectional study to assess the psychological

morbidity of women facing possible miscarriage

Patricia NP Ip, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics & Gynaecology); Karen Ng, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics & Gynaecology); Osanna YK Wan, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics & Gynaecology); Janice WK Kwok, BSc; Jacqueline PW Chung, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics & Gynaecology); Symphorosa SC Chan, MD, FHKCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Patricia NP Ip (patricia.ip@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Threatened miscarriage is a common

complication of pregnancy. This study aimed to

assess psychological morbidity in women with

threatened miscarriage, with the goal of identifying

early interventions for women at risk of anxiety or

depression.

Methods: Women in their first trimester attending

an Early Pregnancy Assessment Clinic were recruited

between July 2013 and June 2015. They were asked to

complete the 12-item General Health Questionnaire

(GHQ-12), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),

Spielberger’s State Anxiety Inventory State form

(STAI-S), the Fatigue Scale–14 (FS-14), and the

Profile of Mood States (POMS) before consultation.

They were also asked to rate anxiety levels before and

after consultation using a visual analogue scale (VAS).

Results: In total, 1390 women completed the study.

The mean ± standard deviation of GHQ-12 (bi-modal)

and GHQ-12 (Likert) scores were 4.04 ±

3.17 and 15.19 ± 5.30, respectively. Among these

women, 48.4% had a GHQ-12 (bi-modal) score

≥4 and 76.7% had a GHQ-12 (Likert) score >12,

indicating distress. The mean ± standard deviation

of BDI, STAI-S, and FS-14 scores were 9.35 ± 7.19,

53.81 ± 10.95, and 2.40 ± 0.51, respectively. The

VAS score significantly decreased after consultation (P<0.001). Compared with women without a history

of miscarriage, women with a previous miscarriage

had higher GHQ-12, BDI, and POMS scores (except

for fatigue-inertia and vigour-activity subscales).

A higher bleeding score was strongly positively

correlated with GHQ-12 (Likert) score. There were

weak correlations between pain score and the

GHQ-12 (bi-modal) ≥4, BDI >12, and POMS scores

(except for confusion-bewilderment subscale which

showed a strong positive correlation).

Conclusion: Women with threatened miscarriage

experience a considerable psychological burden,

emphasising the importance of early recognition for

timely management.

New knowledge added by this study

- A substantial proportion of women with threatened miscarriage had symptoms of anxiety or depression.

- Women with a previous miscarriage had a higher level of distress and would benefit from additional attention and psychological support.

- Women with problems in early pregnancy should receive both clinical and psychological care to alleviate their anxiety.

- Further studies of maternal psychological outcomes and fetal outcomes are needed to determine the long-term effects of anxiety and depression among women with threatened miscarriage in the first trimester.

Introduction

Miscarriage occurs in 10% to 15% of pregnancies,

mainly in the first trimester.1 Spontaneous

miscarriage is associated with psychological

problems such as anxiety and depression.2 3 4 Post-traumatic

stress disorder may also occur after

a miscarriage.3 Threatened miscarriage affects

15% to 20% of pregnant women.5 Management of

threatened miscarriage involves reassurance and

counselling. Women with threatened miscarriage and/or pregnancy-related uncertainty may

experience frustration and anxiety. Although there

are extensive data regarding the association between

miscarriage and psychological morbidity, higher

incidences of anxiety and depression among women

with threatened miscarriage have only been detected

in small studies.6 7

Antenatal depression and anxiety disorders are

associated with increased fetal risks, such as low birth

weight; antenatal symptoms of depression have been positively associated with postnatal depression.8 9

Furthermore, antenatal maternal stress and anxiety

appear to predict long-term behavioural and

emotional problems in children.10 11 Therefore, early

detection and intervention are needed in women

with antenatal psychological symptoms to minimise

the impacts of those symptoms.

This study assessed psychological morbidity in

women with threatened miscarriage, with the goal of

identifying early interventions for women at risk of

anxiety or depression.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study, conducted at a university

hospital in Hong Kong between July 2013 and

June 2015, was part of a study that examined the

ability of an early pregnancy viability scoring

system to support counselling for women.12 In this

hospital, an outpatient Early Pregnancy Assessment

Clinic (EPAC) provides medical care for women

experiencing abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding,

or other problems in early pregnancy (gestational

age ≤12 weeks). Referrals are usually made by

medical officers from the Accident and Emergency

Departments across Hong Kong, as well as general

practitioners. All gynaecologists at the EPAC have ≥3

years of experience performing ultrasound scans. All Chinese women attending the EPAC were invited to

participate; written informed consent was obtained

from women who agreed to take part in the study.

Exclusion criteria were age <18 years, ectopic

pregnancy, multiple pregnancies, gestational age

>84 days (>12 weeks), requested termination of

pregnancy, and loss to follow-up. Demographic

data, obstetric history, smoking status, alcohol

consumption, and body mass index were recorded.

Details of early pregnancy complaints were assessed,

including abdominal pain (graded by a pain score of

0 to 3, where a higher score represents greater pain)

and vaginal bleeding (determined by a pictorial

blood loss chart according to the number of pads

used, where 0 corresponds to no bleeding and 4

corresponds to clots or flooding).

Psychometric instruments

Chinese validated versions of five questionnaires

were used to assess psychological well-being among

the participants: the 12-item General Health

Questionnaire (GHQ-12), the Beck Depression

Inventory (BDI), Spielberger’s State Anxiety

Inventory State form (STAI-S), the Fatigue Scale–14

(FS-14), and the Profile of Mood States (POMS).

All questionnaires have demonstrated reliability

and validity in previous studies.13 14 15 The GHQ-12

and BDI scores were reported as both continuous

and categorical variables, while the scores of

other questionnaires were reported as continuous

variables.

The GHQ-12 is a self-reporting rating scale

intended to identify individuals with reduced

psychological well-being or diminished quality of

life. It is sensitive to short-term psychiatric disorders.

A total score of ≥4 using the bi-modal scoring

method (0-0-1-1) is considered ‘high distress’. When

using the Likert scoring method (0-1-2-3), scores

≤12 are considered normal, while scores >12 are

considered evidence of psychological distress.16 17

The questionnaire has been used as a tool to evaluate

women with miscarriage.18 19 20

The BDI is a 21-item self-reporting rating

scale intended to measure symptoms of depression

in both general and psychiatric populations.21

It is used to measure depression severity, and

psychological morbidity is defined as a score of >12,

indicating probable depressive disorder. The STAI-S

is a 20-item self-reporting inventory that measures

state anxiety, including transitory and situational

feelings of worry.22 Its use has been validated in

pregnant women.23 A higher score indicates a higher

level of anxiety. The FS-14 is a 14-item self-rating

questionnaire that measures fatigue severity. A

lower score indicates a higher level of fatigue.

The POMS is a self-reporting tool for the

assessment of mood alterations in clinical and

psychiatric populations.24 This 65-item questionnaire contains seven components: tension-anxiety,

depression-dejection, anger-hostility, fatigue-inertia,

confusion-bewilderment, vigour-activity, and total

mood disturbance. Scores range from 0 (not at all) to

4 (extremely). Higher positive mood scores indicate

an ideal mood, whereas higher negative mood scores

indicate severe mood disturbance.

In addition to the above questionnaires,

each woman’s level of anxiety and worry before

consultation was assessed using a 0 to 10 cm visual

analogue scale (VAS). A higher value represents

a higher level of anxiety and worry about their

pregnancies. The VAS has previously been validated

with respect to its correlations with other measures

of anxiety.25 26

During the consultation, women were

counselled based on their ultrasound findings and

clinical diagnosis. These women used the VAS to

indicate their level of pregnancy-related anxiety

after consultation. Follow-up scans (1-2 weeks

later) were offered for women with a pregnancy

of uncertain viability. Actual pregnancy outcomes

were reassessed at 13 to 16 weeks, either by phone

or by retrieval of information from the hospital’s

centralised computer antenatal records system.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated based on the number

of participants required for the primary study

to validate the scoring system.12 SPSS software

(Windows version 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States) was used for data entry and analysis.

A 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was calculated

to determine the estimated errors and prevalence.

Descriptive analyses were used for demographic

data. The Chi squared test was used to explore

associations between categorical variables. The

Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare median

values when data were not normally distributed,

while the t test was used to compare means when

data were normally distributed. Univariate analyses

were performed to identify factors associated with

psychological distress or morbidity. Factors with

P values <0.1 in univariate analysis were entered

into multivariate analysis, which was conducted

via binary logistic regression. P values <0.05 were

considered statistically significant.

Results

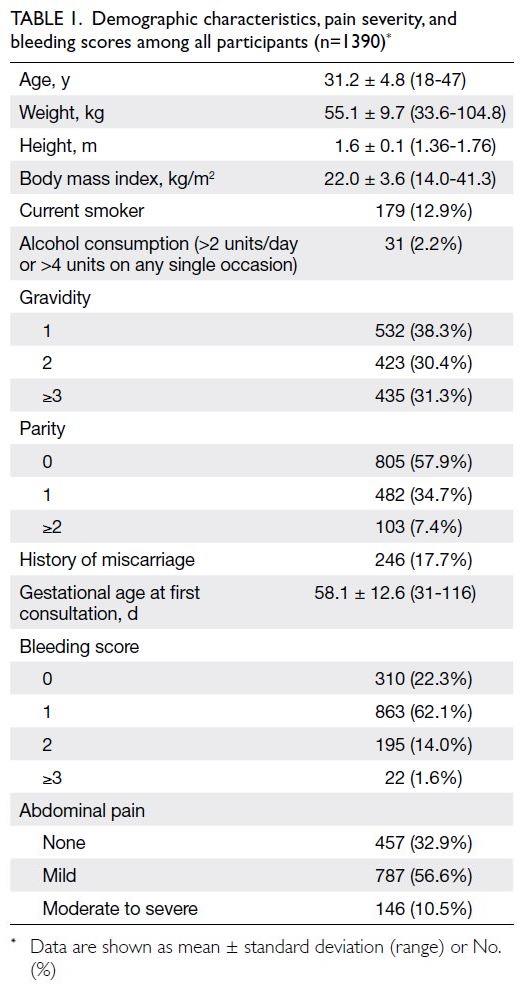

Among the 1508 women who attended the EPAC

during the study period, 64 were excluded and 54

declined to participate; thus, 1390 women completed

the study (Fig). The demographic data are shown

in Table 1. At the first clinic visit, most women

(n=1048, 75.4%) had a viable pregnancy, 223 women

(16.0%) had a pregnancy of uncertain viability, and

119 (8.6%) women had a miscarriage. At 13 to 16

weeks of gestation, 1111 women (79.9%) had a viable

pregnancy, and an additional 160 (11.5%) women

had a miscarriage.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics, pain severity, and bleeding scores among all participants (n=1390)

The GHQ-12 (both bi-modal and Likert), BDI,

STAI-S, FS-14, POMS, and VAS results are presented in Table 2. Overall, 48.4% and 76.7% of women had

a GHQ-12 (bi-modal) score ≥4 and a GHQ-12

(Likert) score >12, respectively, indicating distress.

Among the viable pregnancy, uncertain viability,

and miscarriage groups, the percentages of women

with a GHQ-12 (bi-modal) score ≥4 (43-52%) and a

GHQ-12 (Likert) score >12 (73-83%) were similar.

Women with miscarriage had the highest GHQ-12

score and the highest percentages of a GHQ-12 (bi-modal)

score ≥4 and a GHQ-12 (Likert) score >12. The

miscarriage group also had relatively higher POMS

subscale scores for tension-anxiety, depression-dejection,

anger-hostility, confusion-bewilderment,

and total mood disturbance compared with women

who had other diagnoses.

The VAS scores for anxiety are also presented

in Table 2. The score before consultation was the

highest among women with a miscarriage (mean ±

standard deviation=7.02 ± 2.50). Although the scores for the viable pregnancy and uncertain viability

groups were significantly lower after consultation,

the score was substantially higher in the uncertain

viability group than in the viable pregnancy group.

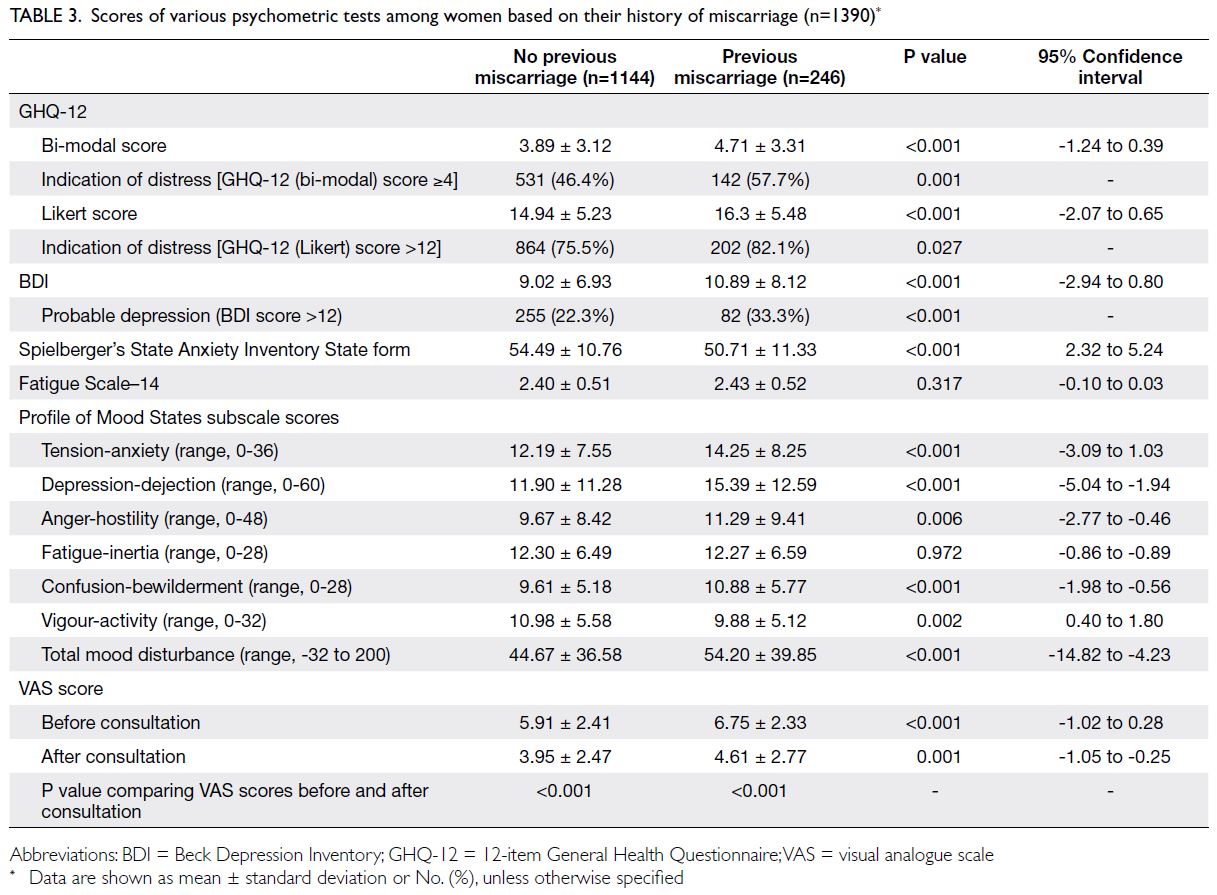

Subgroup analysis showed that GHQ-12, BDI,

and POMS (except fatigue-inertia and vigour-activity

subscales) scores were significantly higher among

women with previous miscarriage than among those

without (Table 3). The bleeding score was strongly

positively correlated with the GHQ-12 (Likert) score

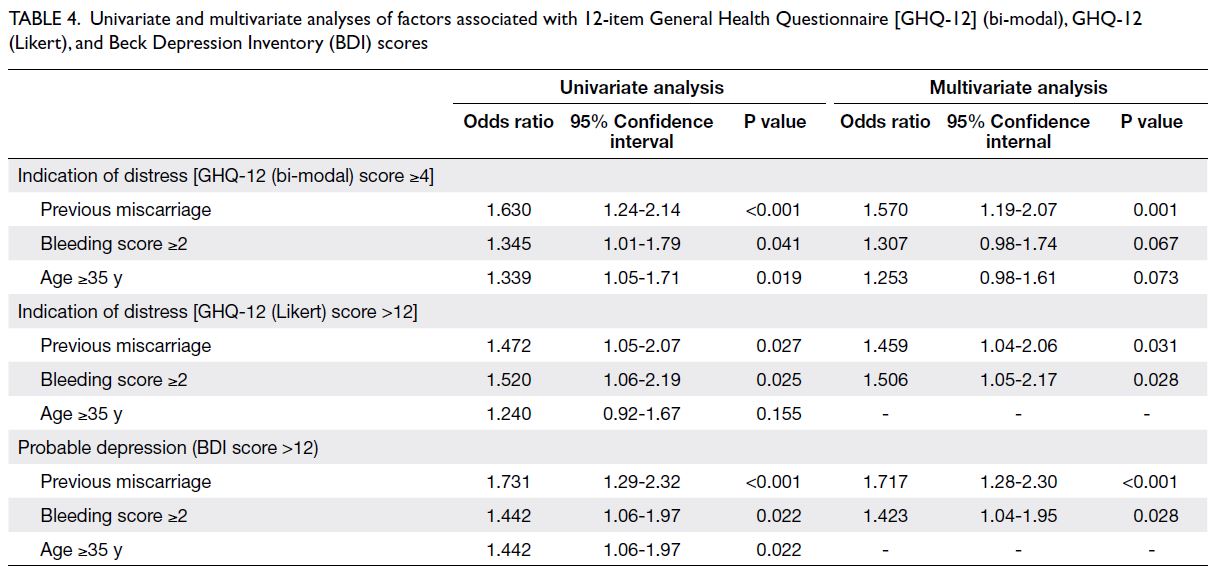

(correlation coefficient=0.56; P=0.032). Univariate

analysis revealed that compared with women who

had a lower bleeding score (<2), women with a higher

bleeding score (≥2) had a significantly higher risk of

having a GHQ-12 (bi-modal) score ≥4 (P=0.041),

a GHQ-12 (Likert) score >12 (P=0.025), and a BDI

score >12 (P=0.022) [Table 4]. There were statistically

significant but weak positive correlations between

the pain score and a GHQ-12 (bi-modal) score ≥4

(P=0.001), a BDI score >12 (P<0.001), and a POMS

total mood disturbance score (P<0.001), as well as

various subscales. Notably, the POMS confusion-bewilderment

subscale (correlation coefficient=0.93;

P<0.001) demonstrated a strong positive correlation

with the pain score.

Table 3. Scores of various psychometric tests among women based on their history of miscarriage (n=1390)

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with 12-item General Health Questionnaire [GHQ-12] (bi-modal), GHQ-12 (Likert), and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores

Statistically significant factors associated with

the various psychometric instrument scores were

subjected to multivariate analysis (Table 4). Previous

miscarriage was an independent risk factor for a

GHQ-12 (bi-modal) score ≥4 (odds ratio [OR]=1.570,

95% CI=1.19-2.07) and a GHQ-12 (Likert) score >12

(OR=1.459, 95% CI=1.04-2.06), indicating distress; it

was also a risk factor for a BDI score >12 (OR=1.717,

95% CI=1.28-2.30), suggesting probable depression.

A bleeding score ≥2 was an independent risk

factor for a GHQ-12 (Likert) score >12 (OR=1.506,

95% CI=1.05-2.17) and a BDI score >12 (OR=1.423,

95% CI=1.04-1.95).

Discussion

In this cohort study, nearly 50% and approximately

77% of women had a GHQ-12 (bi-modal) score ≥4

and a GHQ-12 (Likert) score >12, indicating distress.

Around one-fourth (24.5%) of women had a BDI

score >12, suggesting probable depression.

Regardless of diagnosis, the VAS score

decreased after consultation. However, the decrease

in VAS score was smaller for the uncertain viability

group, which may be attributed to the enhanced

anxiety resulting from uncertainty among these

women. This anxiety would be alleviated after an

ultrasound examination and consultation with an

accurate diagnosis. These findings emphasise the

need to implement an early pregnancy assessment

service that provides both clinical and psychological

guidance to alleviate anxiety among women with

problems in early pregnancy.

Emotional disturbances can have long-term effects on women with a previous miscarriage.

Lok et al19 reported consistently higher scores on the

GHQ-12 and BDI among women with a previous

miscarriage, although these scores could decrease

over time. In the present study, we observed a higher

level of distress among women with a previous

miscarriage, as demonstrated by the significantly

greater proportion of women with GHQ-12 (bi-modal)

score ≥4, GHQ-12 (Likert) score >12, and

BDI score >12. Profile of Mood States scores were

also significantly higher on all subscales, except for

the fatigue-inertia and vigour-activity subscales.

Similarly, the baseline VAS score before consultation

was significantly higher among women with a

previous miscarriage than among those without.

In multivariate analysis, previous miscarriage was

an independent risk factor for GHQ-12 (bi-modal)

score >4, GHQ-12 (Likert) score >12, and BDI

score >12. Baseline psychological morbidity may be

greater among women with a previous miscarriage

than among those without, consistent with findings

in other studies.3 27 Therefore, additional attention

and psychological support would be beneficial for women with greater distress and worse mood status.

A higher pain score was positively correlated

with higher levels of distress and anxiety, as indicated

by the positive relationships with various scales used

in the present study. Pain is associated with anxiety

and depression in pregnant women.28 Nevertheless,

we observed weak relationships between pain and

anxiety or distress, which might be related to the

subjective nature of pain assessment.

Women with moderate to heavy bleeding

(bleeding score ≥2) had significantly higher GHQ-12

(bi-modal), GHQ-12 (Likert), and BDI scores.

Additionally, multivariate analysis showed that

moderate to heavy bleeding (bleeding score ≥2) was

an independent risk factor for a GHQ-12 (bi-modal)

score ≥4, a GHQ-12 (Likert) score >12, and a BDI score

>12. Heavy bleeding is often regarded as a common

sign of threatened miscarriage. These findings

highlight the importance of addressing pain and

bleeding symptoms among women who attend early

pregnancy services. The underlying complications of

pregnancy, as well as anxiety and low mood in affected

women, should be promptly managed.

Pregnancy loss is associated with negative mood

status, including depression and anxiety.3 18 19 27 29

Whereas many studies have investigated the effects

of miscarriage or pregnancy loss on depression,

the effects of threatened miscarriage or early

pregnancy-related complaints on women have not

been extensively explored, despite the burdensome

experience of a threatened miscarriage that

appropriately causing anxiety in affected women.

Our results are consistent with findings by Zhu et al,6

who reported that a substantial proportion of

women with threatened miscarriage had symptoms

of depression or anxiety.

The present study had a large sample size and

a high rate of participation. Additionally, multiple

psychometric instruments were used to assess the

participants. The findings emphasise the importance

of assessing and managing depression and anxiety

symptoms in women with threatened miscarriage.

Mental health assessments should be performed

when women with threatened miscarriage attend

clinics and hospitals. Early recognition of relevant

mood problems will facilitate timely management.

Non-pharmacological interventions, such as

antenatal group therapy, constitute effective

treatment for pregnant women with anxiety

and depression.6 Pharmacological therapies (eg,

most selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

and benzodiazepines) can be administered after

considering the side-effects of medications relative

to the risk of untreated antenatal depression and

anxiety.30

Limitations

Nevertheless, this study had some limitations. First,

it used a cross-sectional design without longitudinal

follow-up, and the subgroup analysis might have been

underpowered. Second, information was unavailable

regarding social factors (eg, education level or

marital status) and the presence of an underlying

psychiatric disorder, which might contribute to

differences in baseline mood status. Third, the study

did not include a comparison group of women

without symptoms of threatened miscarriage.

Conclusion

There is a considerable psychological burden among

women with early pregnancy problems and concerns

about future pregnancy viability. These women

experience emotional disturbances, as indicated by a

significant proportion of women in this study who had

high scores on psychometric tests. A gynaecologist

consultation, in combination with an ultrasound

assessment, is reassuring and can alleviate anxiety

among women with early pregnancy problems. This

study on maternal psychological outcomes provides

insights concerning psychological morbidity among women with threatened miscarriage in the first

trimester, while also demonstrating the usefulness

and feasibility of various psychometric instruments

in identifying women who require additional

psychological support. Further studies exploring

maternal psychological well-being later in pregnancy,

as well as fetal outcomes, are needed to determine

the long-term effects of anxiety and depression

among women with threatened miscarriage in the

first trimester.

Author contributions

Concept or design: OYK Wan, SSC Chan.

Acquisition of data: OYK Wan, JWK Kwok.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PNP Ip, K Ng.

Drafting of the manuscript: PNP Ip, K Ng.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: PNP Ip, K Ng, OYK Wan, JPW Chung, SSC Chan.

Acquisition of data: OYK Wan, JWK Kwok.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PNP Ip, K Ng.

Drafting of the manuscript: PNP Ip, K Ng.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: PNP Ip, K Ng, OYK Wan, JPW Chung, SSC Chan.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, JPW Chung was not involved in

the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no

conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research was supported by a grant from the Health and

Medical Research Fund of the former Food and Health Bureau, Hong

Kong SAR Government (Ref No.: 12131091). The study sponsor was not

involved in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data,

or in the writing of the manuscript.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Joint Chinese University of

Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research

Ethics Committee (Ref No.: CRE.2013.348). Written informed

consent was obtained from all participants.

References

1. Tong S, Kaur A, Walker SP, Bryant V, Onwude JL,

Permezel M. Miscarriage risk for asymptomatic women

after a normal first-trimester prenatal visit. Obstet Gynecol

2008;111:710-4. Crossref

2. Broen AN, Moum T, Bödtker AS, Ekeberg O. Predictors of

anxiety and depression following pregnancy termination:

a longitudinal five-year follow-up study. Acta Obstet

Gynecol Scand 2006;85:317-23. Crossref

3. Farren J, Jalmbrant M, Ameye L, et al. Post-traumatic

stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage or

ectopic pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open

2016;6:e011864. Crossref

4. Jensen KL, Temple-Smith MJ, Bilardi JE. Health

professionals’ roles and practices in supporting women

experiencing miscarriage: a qualitative study. Aust N Z J

Obstet Gynaecol 2019;59:508-13. Crossref

5. Park C, Kang MY, Kim D, Park J, Eom H, Kim EA.

Prevalence of abortion and adverse pregnancy outcomes

among working women in Korea: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0182341. Crossref

6. Zhu CS, Tan TC, Chen HY, Malhotra R, Allen JC, Østbye T.

Threatened miscarriage and depressive and anxiety

symptoms among women and partners in early pregnancy.

J Affect Disord 2018;237:1-9. Crossref

7. Aksoy H, Aksoy Ü, İdem Karadağ Ö, et al. Effect of

threatened miscarriage on maternal mood: a prospective

controlled cohort study. J Clin Obstet Gynecol 2015;25:92-8. Crossref

8. Gelaye B, Sanchez SE, Andrade A, et al. Association

of antepartum depression, generalized anxiety, and

posttraumatic stress disorder with infant birth weight and

gestational age at delivery. J Affect Disord 2020;262:310-6. Crossref

9. Siu BW, Leung SS, Ip P, Hung SF, O’Hara MW. Antenatal

risk factors for postnatal depression: a prospective study of

Chinese women at maternal and child health centres. BMC

Psychiatry 2012;12:22. Crossref

10. Ibanez G, Bernard JY, Rondet C, et al. Effects of antenatal

maternal depression and anxiety on children’s early

cognitive development: a prospective cohort study. PLoS

One 2015;10:e0135849. Crossref

11. O’Connor TG, Heron J, Golding J, Glover V; ALSPAC

Study Team. Maternal antenatal anxiety and behavioural/emotional problems in children: a test of a programming

hypothesis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2003;44:1025-36. Crossref

12. Wan OY, Chan SS, Chung JP, Kwok JW, Lao TT, Sahota DS.

External validation of a simple scoring system to

predict pregnancy viability in women presenting to an

early pregnancy assessment clinic. Hong Kong Med J

2020;26:102-10. Crossref

13. Chan DW, Chan TS. Reliability, validity and the structure

of the General Health Questionnaire in a Chinese context.

Psychol Med 1983;13:363-71. Crossref

14. Shek DT. Reliability and factorial structure of the Chinese

version of the Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol

1990;46:35-43. Crossref

15. Shek DT. Reliability and factorial structure of the Chinese

version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. J Psychopathol

Behav Assess 1988;10:303-17. Crossref

16. Liang Y, Wang L, Yin X. The factor structure of the 12-item

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) in young Chinese

civil servants. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016;14:136. Crossref

17. Rao WW, Yang MJ, Cao BN, et al. Psychological distress in

cancer patients in a large Chinese cross-sectional study. J

Affect Disord 2019;245:950-6. Crossref

18. Lok IH, Lee DT, Yip SK, Shek D, Tam WH, Chung TK.

Screening for post-miscarriage psychiatric morbidity. Am

J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:546-50. Crossref

19. Lok IH, Yip AS, Lee DT, Sahota D, Chung TK. A 1-year

longitudinal study of psychological morbidity after

miscarriage. Fertil Steril 2010;93:1966-75. Crossref

20. Kong GW, Lok IH, Yiu AK, Hui AS, Lai BP, Chung TK.

Clinical and psychological impact after surgical, medical

or expectant management of first-trimester miscarriage—a

randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol

2013;53:170-7. Crossref

21. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An

inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry

1961;4:561-71. Crossref

22. Hedberg AG. Review of State–Trait Anxiety Inventory.

[Review of the Book State–Trait Anxiety Inventory, by C.

D. Spielberger, R. L. Gorsuch & R. E. Lushere]. Prof Psychol

1972;3:389-90. Crossref

23. Bann CM, Parker CB, Grobman WA, et al. Psychometric

properties of stress and anxiety measures among

nulliparous women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol

2017;38:53-62. Crossref

24. McNair DM, Heuchert P. Profile of mood states: technical

update. North Tonawanda (NY): Multi-Health Systems;

2013. Crossref

25. Williams VS, Morlock RJ, Feltner D. Psychometric

evaluation of a visual analog scale for the assessment of

anxiety. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:57. Crossref

26. Facco E, Stellini E, Bacci C, et al. Validation of visual

analogue scale for anxiety (VAS-A) in preanesthesia

evaluation. Minerva Anestesiol 2013;79:1389-95.

27. Cumming GP, Klein S, Bolsover D, et al. The emotional

burden of miscarriage for women and their partners:

trajectories of anxiety and depression over 13 months.

BJOG 2007;114:1138-45. Crossref

28. Virgara R, Maher C, Van Kessel G. The comorbidity of

low back pelvic pain and risk of depression and anxiety

in pregnancy in primiparous women. BMC Pregnancy

Childbirth 2018;18:288. Crossref

29. Kong GW, Lok IH, Lam PM, Yip AS, Chung TK. Conflicting

perceptions between health care professionals and patients

on the psychological morbidity following miscarriage. Aust

N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2010;50:562-7. Crossref

30. Vitale SG, Laganà AS, Muscatello MR, et al.

Psychopharmacotherapy in pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Obstet Gynecol Surv 2016;71:721-33. Crossref