Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Feb;24(1):48–55 | Epub 5 Jan 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176984

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Injuries and envenomation by exotic pets in Hong Kong

Vember CH Ng, FHKCEM, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1;

Albert CH Lit, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)2; OF Wong,

FHKAM (Anaesthesiology), FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)2; ML Tse,

FHKCEM, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1; HT Fung, FRCSEd, FHKAM

(Emergency Medicine)3

1 Hong Kong Poison Information Centre,

United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

2 Accident and Emergency Department,

North Lantau Hospital, Tung Chung, Lantau, Hong Kong

3 Accident and Emergency Department,

Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr OF Wong (oifungwong@yahoo.com.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Exotic pets are

increasingly popular in Hong Kong and include fish, amphibians,

reptiles, and arthropods. Some of these exotic animals are venomous and

may cause injuries to and envenomation of their owners. The clinical

experience of emergency physicians in the management of injuries and

envenomation by these exotic animals is limited. We reviewed the

clinical features and outcomes of injuries and envenomation by exotic

pets recorded by the Hong Kong Poison Information Centre.

Methods: We retrospectively

retrieved and reviewed cases of injuries and envenomation by exotic pets

recorded by the Hong Kong Poison Information Centre from 1 July 2008 to

31 March 2017.

Results: There were 15 reported

cases of injuries and envenomation by exotic pets during the study

period, including snakebite (n=6), fish sting (n=4), scorpion sting

(n=2), lizard bite (n=2), and turtle bite (n=1). There were two cases of

major effects from the envenomation, seven cases with moderate effects,

and six cases with mild effects. All major effects were related to

venomous snakebites. There were no mortalities.

Conclusion: All human injuries

from exotic pets arose from reptiles, scorpions, and fish. All cases of

major envenomation were inflicted by snakes.

New knowledge added by this study

- This is the first case series of injuries and envenomation by exotic pets in Hong Kong.

- Reptiles, scorpions, and fish that are kept as exotic pets can potentially cause injuries to and envenomation of their owners.

- All cases of major envenomation were inflicted by snakes. Envenomation by a highly venomous exotic snake was also encountered.

- A variety of exotic animals, including venomous species, are kept as pets in Hong Kong. Emergency physicians in Hong Kong, however, have limited knowledge about the management of injuries caused by these exotic animals.

- The Hong Kong Poison Information Centre provides an expert consultation service for the management of injuries and envenomation by such exotic animals.

Introduction

A variety of exotic animals are kept as ‘pets’

including fish, amphibians, reptiles, and arthropods. The keeping of

exotic, and sometimes venomous pets, is becoming increasingly common

worldwide. Some of these exotic pets are capable of causing injury to or

even life-threatening envenomation of their owners.1

Reptiles are the most popular exotic pets

worldwide. It has been estimated that 1.5 to 2.0 million households in the

United States (US) own one or more pet reptiles. Snakes account for

approximately 11% of the imported reptiles in the US, and up to 9% of

these are venomous.2 Envenomation

by exotic pets, particularly snakes, is an increasing cause for concern in

both the US and Europe.3 In a study

of exotic snake envenomation in the US, data from the National Poison Data

System database revealed 258 cases of exotic snakebites involving at least

61 unique exotic venomous species between 2005 and 2011. Among these, 40%

of bites occurred in a private residence.4

Another study of bites and stings by exotic pets in Europe reported 404

cases in four poison centres in Germany and France from 1996 to 2006.

Exotic snakebites from rattlesnakes, cobras, mambas, and other venomous

snakes were the cause of approximately 40% of envenomations.5 Another survey conducted in the United Kingdom reviewed

the data from the National Health Service Health Episode Statistics from

2004 to 2010. A total of 709 hospital admissions associated with injuries

from exotic pets were reported and approximately 300 hospital admissions

were related to contact with scorpions, venomous snakes, and lizards.6 Nonetheless, no such epidemiological study has been

conducted in Hong Kong. According to the thematic household survey report

in 2006, 286 300 households in Hong Kong kept pets at home, of which 5%

were pets other than dogs, cats, turtles, tortoises, birds, hamsters, and

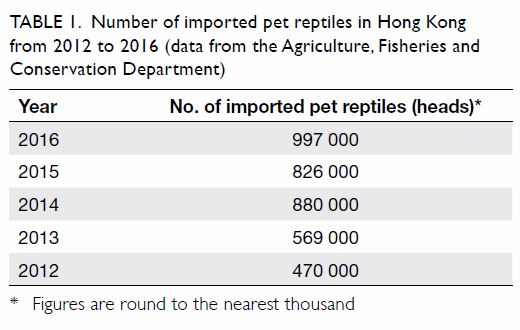

rabbits.7 The number of imported

pet reptiles into Hong Kong has increased rapidly in recent years. In

2016, the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department (AFCD)

recorded that almost 1 000 000 pet reptiles were imported into Hong Kong (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of imported pet reptiles in Hong Kong from 2012 to 2016 (data from the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department)

The knowledge of local emergency physicians about

the management of injuries by these exotic animals is limited. Since 2005,

the Hong Kong Poison Information Centre (HKPIC) has provided a 24-hour

telephone consultation service (tel: 2635 1111) for health care

professionals in Hong Kong, offering poison information and clinical

management advice. The objectives of this study were to use HKPIC records

to describe the variety of reported exotic species and the clinical

features and outcomes of injuries and envenomation caused by exotic pets.

Methods

This was a case series based on the database of the

HKPIC. It included cases encountered by clinical frontline staff and

surveillance data from routine reporting of poisoning cases by all

accident and emergency departments (AEDs) under the Hospital Authority

(HA). Cases of injuries and envenomation by exotic pets recorded by the

HKPIC from 1 July 2008 to 31 March 2017 were retrospectively retrieved.

Demographic data of the patients—including the involved species, clinical

presentations, and outcomes—were reviewed from the patient electronic

Health Record. This study was done in accordance with the principles

outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The severity of injuries and the effects of

envenomation were defined as major (life-threatening or resulting in

significant residual disability or disfigurement), moderate (pronounced,

prolonged, or systemic signs and symptoms), or mild (minimal and rapidly

resolving signs and symptoms).

Results

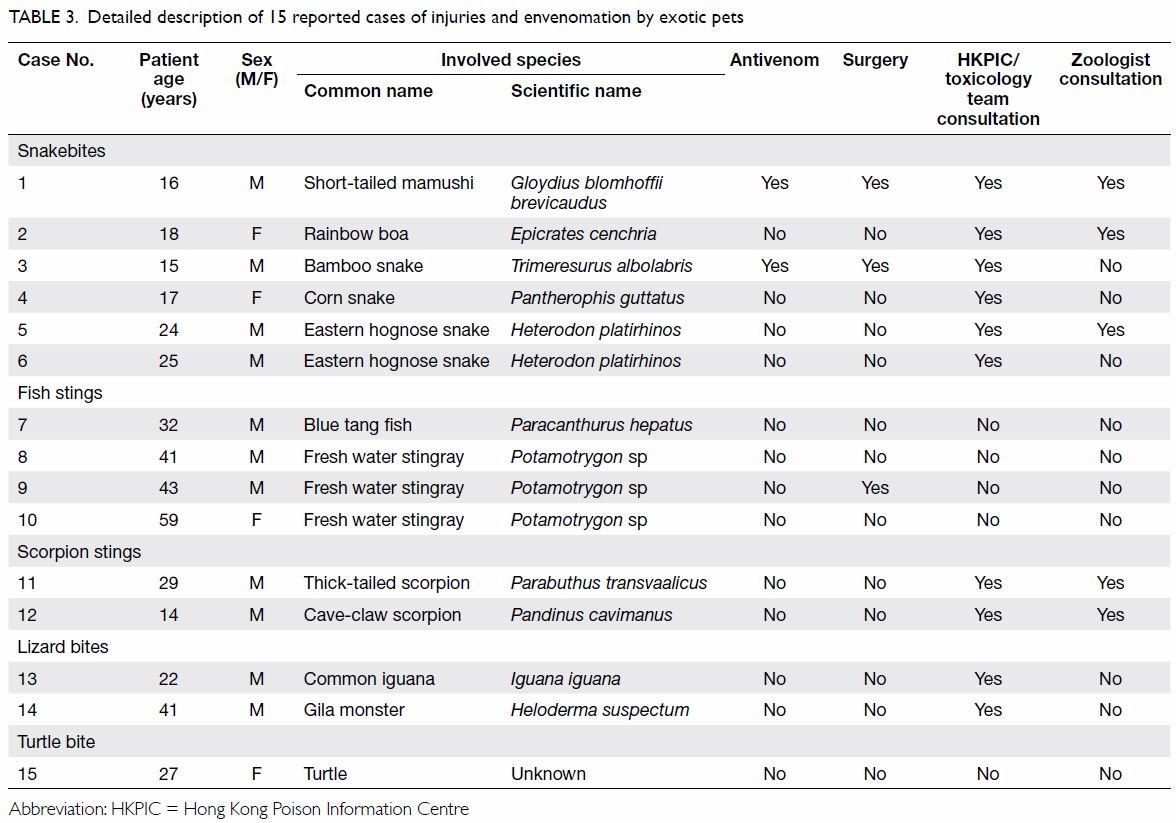

During the study period, 15 cases of injuries and

envenomation by exotic pets were reported to the HKPIC. Among the 15

patients, nine consulted the HKPIC for management advice and one was

managed by the toxicology team of the AED. Local zoologists were consulted

in five cases for species identification and opinion about the venomous

nature of the species. All bites and stings were unintentional and

occurred in a private household. The mean age of the exotic pet owners was

28.2 (range, 14-59) years and the majority (73%) were male. There were six

cases of snakebite, four cases of fish sting, two cases of scorpion sting,

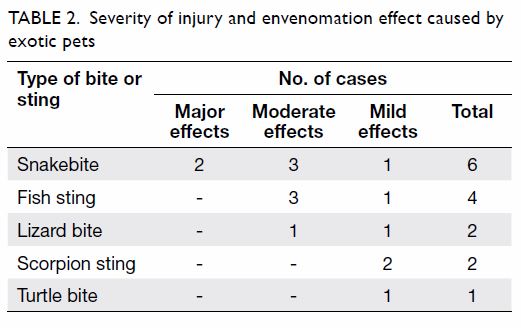

two cases of lizard bite, and one case of turtle bite. The severity of

injury and envenomation effect are summarised in Table 2.

All major effects occurred in patients with

snakebite. A 16-year-old boy was bitten by a short-tailed mamushi (Gloydius

blomhoffii brevicaudus; Fig 1a) on his left middle finger. The short-tailed

mamushi is not native to Hong Kong but was being kept as a pet. The

patient had a history of snakebite by a bamboo snake (Trimeresurus

albolabris) that required antivenom treatment, sustained while

attempting to catch the snake in the suburbs. Following the bite by the

short-tailed mamushi, the patient developed severe local envenomation over

his left hand and required admission to the intensive care unit for close

observation of the rapidly progressing local envenomation. No systemic

envenomation was observed. A local zoologist was consulted for snake

identification. A total of three vials of antivenom for Agkistrodon

halys were administered as treatment but ischaemia due to

compartment syndrome developed in the left hand. Debridement and

fasciotomy were eventually performed. The patient had a residual flexion

contraction deformity of his left middle finger 2 months later. He

recovered with full movement of the left middle finger 6 months after the

injury. Another boy, aged 15 years, was bitten by a bamboo snake on his

left thumb. The snake had been caught by the patient in the suburbs and

kept as a pet. He developed severe local envenomation and was given three

vials of antivenom for Agkistrodon halys and three vials of

antivenom for green pit viper. The patient developed tenosynovitis of his

left thumb and required emergency surgery for debridement. Another four

patients were bitten by ‘nonvenomous’ snakes including a rainbow boa (Epicrates

cenchria; Fig 1b), corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus),

and eastern hognose snake (Heterodon platirhinos; Fig

1c). All snakes were kept as pets. An 18-year-old girl was

accidentally bitten by a rainbow boa on her left hand but had no signs of

local or systemic envenomation after the injury. Another patient developed

a wound infection after being bitten by a corn snake 2 weeks previously (Fig 1d). She recovered after a course of antibiotic

therapy. Two young men were bitten by hognose snakes. One developed local

envenomation with progressive swelling over the injured hand (Fig

1e). The local envenomation resolved with conservative management.

The HKPIC was consulted in all cases, of which three required consultation

with a zoologist.

Figure 1. (a) Short-tailed mamushi (Gloydius blomhoffii brevicaudus), (b) rainbow boa (Epicrates cenchria), and (c) eastern hognose snake (Heterodon platirhinos). (d) Local wound infection after being bitten by a corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus), and (e) local envenomation after a bite by an eastern hognose snake

Injuries from reptiles other than snakes were also

recorded. There were two cases of lizard bite. In one case, a 22-year-old

man was bitten by a common iguana (Iguana iguana) on his left

wrist. In the other case, a 41-year-old man presented to the AED

approximately 2 hours after being bitten on his right hand by a Gila

monster (Fig 2a). He developed intense pain and local

swelling over the site of injury. The pain lasted for about 12 hours and

then gradually improved. His haemodynamic state remained stable and no

airway oedema or neurological symptoms were observed during his stay in

the emergency medicine ward. He was eventually discharged. A young woman

attended the AED because of a turtle bite over her left face with

consequent minor physical injury.

Figure 2. (a) Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) and (b) freshwater stingray (Potamotrygon species). (c) Thick-tailed scorpion (Parabuthus transvaalicus) and (d) cave-claw scorpion (Pandinus cavimanus). (e) Wound infection after cave-claw scorpion sting

Stings by aquarium fish were the second most common

injuries by exotic pets. Four cases were recorded, including one sting by

a blue tang fish and three by freshwater stingrays (Fig 2b). All patients developed severe pain over the

site of injury that responded to immersion in hot water. One of the

patients with a freshwater stingray sting developed a wound infection that

required emergency surgery for wound exploration and irrigation.

Two male patients were stung by their pet

scorpions: a thick-tailed scorpion (Parabuthus transvaalicus; Fig

2c) and a cave-claw scorpion (Pandinus cavimanus; Fig

2d). No systemic envenomation was observed. The patient with the

cave-claw scorpion sting developed a local wound infection (Fig

2e) that recovered after a course of antibiotics.

The characteristics and management of the 15 cases

are summarised in Table 3.

Discussion

Injuries by a variety of exotic pets were

encountered in this study. More than half of the injuries (9/15) were

inflicted by reptiles. Reptiles are becoming increasingly popular to keep

as pets in Hong Kong. According to the records of the AFCD over the past 5

years, the top 10 most common reptile species imported to Hong Kong are

the European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis), razor-backed musk

turtle (Sternotherus carinatus), common snapping turtle (Chelydra

serpentina), red-bellied cooter (Pseudemys nelsoni), yellow-spotted Amazon

River turtle (Podocnemis unifilis), Hermann’s tortoise (Testudo

hermanni), African spurred tortoise (Geochelone sulcata),

leopard tortoise (Stigmochelys pardalis), common iguana (Iguana

iguana), and ball python (Python regius). Commonly imported

pet snakes include the ball python (Python regius), king snake (Lampropeltis

getula), corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus), rat snake (Elaphe

obsoleta), milk snake (Lampropeltis triangulum), and western

hognose snake (Heterodon nasicus). With the exception of the

hognose snake, which is a mildly venomous species, they are all

nonvenomous. Nonetheless, a much wider variety of species, including

venomous reptiles, may be sold on the black market. Bites may occur during

the care and handling of these exotic animals.3

Envenomation by exotic venomous species is an uncommon but often serious

medical emergency.

The keeping of venomous snakes is common in the US.4 Amateur collectors are at risk of

bites and envenomation and fatalities have been reported.8 Although envenomation from exotic snakes is rarely

encountered in Hong Kong, it poses a great challenge to emergency

physicians owing to their lack of experience and limited supplies of

antivenom, as illustrated by our case of bite by a short-tailed mamushi.

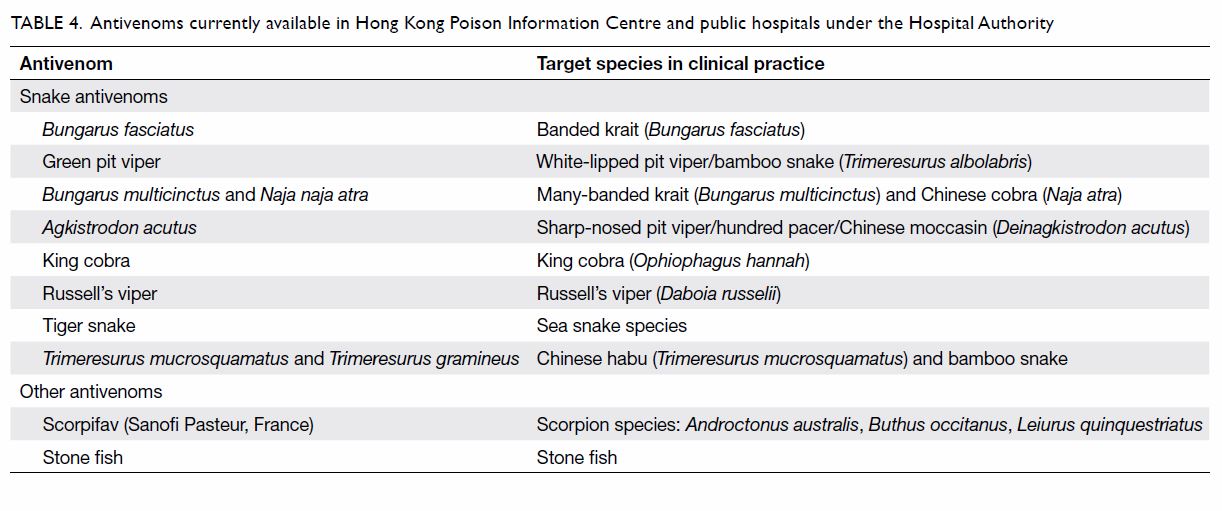

Currently, the HA stocks principally snake antivenom for local venomous

species (Table 4). Bites by nonvenomous pet snakes may also

result in local envenomation and complications; for instance, although the

hognose snake is known as a nonvenomous species, one patient developed

local envenomation after being bitten. Another patient developed a wound

infection after being bitten by a corn snake.

Table 4. Antivenoms currently available in the Hong Kong Poison Information Centre and public hospitals under the Hospital Authority

As well as snakes, lizards are popular as pets.

Bites by large species such as the common green iguana (Iguana iguana)

can result in serious injury.9

Envenomation from lizard bites is rare in Hong Kong. Two lizards are well

known to be venomous: the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum)10 and the Mexican beaded lizard (Heloderma horridum).11 12

Both have venom-secreting glands and bites. The Gila monster is native to

the southwestern US extending into Mexico, whereas the beaded lizard is

native only to Mexico. The Gila monster is listed in the Convention on

International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

as a protected species.13

Captive-bred Gila monsters are traded in international pet markets. Venom

of the Gila monster consists of a variety of proteins including gilatoxin,

a kallikrein-like protease that can hydrolyse kininogen and produce

bradykinin.11 14 The common envenomation effects are intense pain at

the injured site, oedema, paraesthesia, weakness, dizziness, and nausea.

Hypotension occurs in severe envenomation.15

The intense pain, oedema, and hypotension are likely due to the

bradykinin-mediated effects. Airway oedema has been reported regardless of

the site of bite and may occur up to 12 hours after the bite.14 Nevertheless, severe envenomation from the Gila

monster occurs in only a minority of patients. In a retrospective study of

all cases of Gila monster bite reported to the two Arizona poison control

centres from 2000 to 2011, 105 cases of human exposure to Gila monsters

were recorded and 70 cases were referred to health care facilities for

medical treatment. Eleven cases required admission to hospital and five

required care in an intensive care unit. Six patients developed airway

oedema and three required emergent airway management including one

cricothyrotomy.14 Treatment of

Gila monster bites is mainly supportive. Intravenous crystalloid infusion

and vasopressors may be required for treatment of hypotension in severe

envenomation. Radiographic assessment is needed to look for retained teeth

and subcutaneous air due to the chewing-like action during the bites.16 No antivenom to Gila monster is commercially

available.17 Observation for at

least 12 hours after the bite for delayed-onset airway oedema is

recommended.14

Among all the reptiles, tortoises and turtles are

the most popular in pet markets. All species of tortoises and turtles are

nonvenomous although some, such as the alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys

temminckii) and the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina),

are aggressive and can grow to a very large size. Bites by these large

species can result in severe limb injuries.18

Stings by aquarium fish contributed to the second

largest group of injuries in our case series. The most commonly

encountered aquarium fish was freshwater stingray. Freshwater stingrays (Potamotrygon

species) are native to South America. They are regarded as dangerous by

the native people of the Amazon and frequent sting during fishing season.19 Freshwater stingrays are not

aggressive by nature; stings frequently occur when people step on them or

handle them improperly. Different species of freshwater stingrays have

different colour patterns on their body. They are popular aquarium fish as

they are easy to keep although stings may result in severe envenomation.20 The most common feature of

envenomation from freshwater stingrays is intense local pain. Systemic

manifestations are rare. Skin necrosis is frequently observed in victims

wounded by large freshwater stingrays in the wild.21 In addition, skin necrosis is more commonly observed

in victims injured by freshwater stingrays than marine stingrays. A study

of tissue extracts from the stingers of freshwater and marine stingrays

showed that both tissue extracts had gelatinolytic, caseinolytic, and

fibrinogenolytic activity but hyaluronidase activity was detected only in

the extracts from freshwater stingrays.22

In our case series, no patient injured by a freshwater stingray developed

skin necrosis. The risk of developing skin necrosis is likely related to

the venom load. Larger stingrays possess a much larger venom load in their

stingers. Small freshwater stingrays are commonly kept in an aquarium and

skin necrosis as a result of their sting is uncommon. Hot water immersion

is effective in controlling acute pain but does not prevent skin necrosis.21 Wounds caused by freshwater

stingray stings such as the Aeromonas species can be complicated

by severe secondary infection with virulent bacteria.23 Prophylactic antibiotic is often required.

Apart from freshwater stingrays, the stinging

catfish (Heteropneustes fossilis) is another commonly reported

freshwater aquarium fish that can cause injuries and envenomation. It

possesses venom in the sting that is located in front of the soft-rayed

portion of the pectoral and dorsal fins. Apart from intense local pain,

systemic envenomation including weakness and hypotension can result from a

sting.24 25 There was no case reported to the HKPIC of injury by

this venomous catfish during the study period. Coral reef fish are also

popular pets in Hong Kong. Some coral reef fish, such as the lionfish (Pterois

volitans), are venomous.26

Nonetheless, injuries by aquarium coral reef fish were rarely encountered

in the AED of Hong Kong.

Exotic pet owners also enjoy keeping arthropods

such as scorpions and spiders. There are approximately 2000 species of

scorpion in the world but only a few (30 to 40) are highly venomous and

able to cause severe envenomation in humans.27

Scorpion envenomation is reported throughout the world, mainly in

subtropical and tropical regions.28

The majority of scorpion stings cause mild or no envenomation. Species

that cause serious medical problems mainly belong to the Buthidae family.

The genera of the Buthidae family include Centruroides, Tityus,

Leiurus, Androctonus, Buthus and Parabuthus.29 Scorpions have a special venom

apparatus, the telson, that produces venom. Scorpion venom comprises

numerous toxins including several neurotoxins. Unlike snake venom,

scorpion venom generally lacks enzyme activity. The main molecular targets

of scorpion neurotoxins are the voltage-gated sodium channels and the

voltage-gated potassium channels. Scorpion α-toxin, one of the most

medically important neurotoxins in the scorpion venom, acts on the

voltage-gated sodium channels. Once the toxin binds to voltage-gated

sodium channels, it inhibits inactivation of the channel with consequent

prolonged depolarisation and, hence, neuronal excitation. The autonomic

centres, both sympathetic and parasympathetic, are stimulated. In most

situations of scorpion envenomation, the sympathetic nerves are

predominantly affected. Scorpion envenomation is characterised by

relatively similar neurotoxic excitation syndromes, irrespective of the

species. Parasympathetic effects tend to occur early and then sympathetic

effects persist due to the release of catecholamines that are responsible

for the severe envenomation. Parasympathetic (cholinergic) effects include

hypersalivation, diaphoresis, lacrimation, miosis, diarrhoea, vomiting,

bradycardia, hypotension, increased respiratory secretion, and priapism.

Sympathetic (adrenergic) effects are manifested as tachycardia,

hypertension, mydriasis, hyperthermia, hyperglycaemia, and agitation.

Fatal effects of scorpion envenomation are largely due to cardiovascular

effects. Various cardiac conduction abnormalities have been reported in

patients with scorpion envenomation as well as catecholamine-induced

cardiomyopathy, pulmonary oedema, and cardiogenic shock. Other

manifestations of systemic envenomation include vomiting, abdominal pain,

abnormal oculomotor movements, muscle fasciculation, and spasms of the

face and limbs.29 Pancreatitis is

also a well-reported complication of envenomation by certain species, such

as Leiurus quinquestriatus.30

Nonetheless, severe local envenomation is generally uncommon. Differences

in the clinical manifestations of systemic envenomation exist in some

species. Delayed localised necrosis has been reported in patients stung by

an Iranian scorpion (Hemiscorpius lepturus).31 Patients with envenomation from the thick-tailed

scorpion (Parabuthus transvaalicus) in Zimbabwe have been reported

to develop predominant symptoms from parasympathetic nerve system

stimulation, including profuse sialorrhoea, sweating, and urinary

retention, in the absence of sympathetic stimulation.32

Scorpion stings and envenomation are uncommon in

Hong Kong. Most of the locally reported cases of scorpion sting occurred

while patients were handling langsat, a type of tropical fruit from

South-East Asia. The Chinese stropped bark scorpion (Lychas mucronatus)

hides in the fruit and is subsequently imported into Hong Kong.33 Scorpions are also sold as fish food in aquarium

shops in Hong Kong. People use scorpions to feed arowana, which are

popular aquarium fish. Importation of endangered scorpion species

(CITES-listed species) for commercial purposes is regulated by the

Protection of Endangered Species of Animals and Plants Ordinance Cap. 586

in Hong Kong.34 According to the

data from the AFCD for importation of CITES-listed scorpions, more than

1000 heads of emperor scorpion (Pandinus imperator) have been

imported as pets to Hong Kong each year for the last 4 years. The emperor

scorpion is a nonvenomous species and is native to the rainforests and

savannas of West Africa. Most scorpions in the pet trade, such as the

forest scorpion (Heterometrus species), have no potential for

dangerous envenomation. Nonetheless venomous species may also be kept by

hobbyists and severe envenomation may occur after stings.

Management of scorpion stings includes local wound

care and supportive care for systemic envenomation. Expert opinion should

be sought from a zoologist for species identification and to determine the

venomous nature of the species. Patients with severe systemic envenomation

may require antivenom therapy. Specific antivenom (Scorpifav; Sanofi

Pasteur, France) for Androctonus australis, Buthus occitanus,

and Leiurus quinquestriatus is currently available in the HKPIC.

Spiders, such as tarantulas, are popular exotic

pets and are common in the pet trade in Hong Kong. Nonetheless,

inexperienced owners may be unaware of the potential risk of ocular injury

from the barbed urticating hairs on the abdomen of the tarantulas. Eye

injuries occur when the barbed hairs come into contact with the eyes,

either directly from the tarantula’s ejection or when the owners rub their

eyes after handling the spider.35

Embedment of the hairs in the cornea can result in severe complications,

including ophthalmia nodosa, iritis, and even permanent visual impairment.36 37

Conclusion

The diversity of pets is changing and keeping

exotic animals is increasingly popular. Injuries from these exotic pets

are expected to increase and envenomation may result from stings or bites

from some species. In our case series, reptiles, scorpions, and fish were

responsible for human injuries, and all cases of major envenomation were

inflicted by snakes. Emergency physicians need to be aware of the

appropriate management of injuries and envenomation by these exotic

animals. The HKPIC plays an important role in the provision of expert

advice about management of these special toxicological cases.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank AFCD for providing

the data of imported reptiles, scorpions, and spiders.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

References

1. Bey TA, Boyer LV, Walter FG, McNally J,

Desai H. Exotic snakebite: envenomation by an African puff adder (Bitis

arietans). J Emerg Med 1997;15:827-31. Crossref

2. McNally J, Boesen K, Boyer L.

Toxicologic information resources for reptile envenomations. Vet Clin

North Am Exot Anim Pract 2008;11:389-401. Crossref

3. de Haro L, Pommier P. Envenomation: a

real risk of keeping exotic house pets. Vet Hum Toxicol 2003;45:214-6.

4. Warrick BJ, Boyer LV, Seifert SA.

Non-native (exotic) snake envenomations in the U.S., 2005-2011. Toxins

(Basel) 2014;6:2899-911. Crossref

5. Schaper A, Desel H, Ebbecke M, et al.

Bites and stings by exotic pets in Europe: an 11 year analysis of 404

cases from Northeastern Germany and Southeastern France. Clin Toxicol

(Phila) 2009;47:39-43. Crossref

6. Warwick C, Steedman C. Injuries,

envenomations and stings from exotic pets. J R Soc Med 2012;105:296-9. Crossref

7. Thematic household survey report 2006.

Census and Statistics Department, HKSAR Government. Available from:

http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/ B11302262006XXXXB0100.pdf. Accessed 1

Jun 2017.

8. Marsh N, DeRoos F, Touger M. Gaboon

viper (Bitis gabonica) envenomation resulting from captive

specimens—a review of five cases. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45:60-4. Crossref

9. Heffelfinger RN, Loftus P, Cabrera C,

Pribitkin EA. Lizard bites of the head and neck. J Emerg Med

2012;43:627-9. Crossref

10. Hooker KR, Caravati EM, Hartsell SC.

Gila monster envenomation. Ann Emerg Med 1994;24:731-5. Crossref

11. Cantrell FL. Envenomation by the

Mexican beaded lizard: a case report. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol

2003;41:241-4.Crossref

12. Ariano-Sánchez D. Envenomation by a

wild Guatemalan beaded lizard Heloderma horridum charlesbogerti.

Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46:897-9. Crossref

13. Wijnstekers W. The Convention on

International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

(CITES)—35 years of global efforts to ensure that international trade in

wild animals and plants is legal and sustainable. Forensic Sci Rev

2011;23:1-8.

14. French R, Brooks D, Ruha AM, et al.

Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) envenomation: descriptive

analysis of calls to United States Poison Centers with focus on Arizona

cases. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2015;53:60-70. Crossref

15. Piacentine J, Curry SC, Ryan PJ.

Life-threatening anaphylaxis following gila monster bite. Ann Emerg Med

1986;15:959-61. Crossref

16. French RN, Ash J, Brooks DE. Gila

monster bite. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2012;50:151-2. Crossref

17. Miller MF. Gila monster envenomation.

Ann Emerg Med 1995;25:720. Crossref

18. Johnson RD, Nielsen CL. Traumatic

amputation of finger from an alligator snapping turtle bite. Wilderness

Environ Med 2016;27:277-81. Crossref

19. Junior VH, Cardoso JL, Neto DG.

Injuries by marine and freshwater stingrays: history, clinical aspects of

the envenomations and current status of a neglected problem in Brazil. J

Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2013;19:16. Crossref

20. Brisset IB, Schaper A, Pommier P, de

Haro L. Envenomation by Amazonian freshwater stingray Potamotrygon

motoro: 2 cases reported in Europe. Toxicon 2006;47:32-4. Crossref

21. Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto

JB, de Luna Marques FP, Barbaro KC. Freshwater stingrays: study of

epidemiologic, clinic and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in

humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon 2004;43:287-94.

Crossref

22. Barbaro KC, Lira MS, Malta MB, et al.

Comparative study on extracts from the tissue covering the stingers of

freshwater (Potamotrygon falkneri) and marine (Dasyatis guttata)

stingrays. Toxicon 2007;50:676-87. Crossref

23. Polack FP, Coluccio M, Ruttimann R,

Gaivironsky RA, Polack NR. Infected stingray injury. Pediatr Infect Dis J

1998;17:349,360.

24. Dorooshi G. Catfish stings: a report

of two cases. J Res Med Sci 2012;17:578-81.

25. Satora L, Kuciel M, Gawlikowski T.

Catfish stings and the venom apparatus of the African catfish Clarias

gariepinus (Burchell, 1822), and stinging catfish Heteropneustes

fossilis (Bloch, 1794). Ann Agric Environ Med 2008;15:163-6.

26. Chan HY, Chan YC, Tse ML, Lau FL.

Venomous fish sting cases reported to Hong Kong Poison Information Centre:

a three-year retrospective study on epidemiology and management. Hong Kong

J Emerg Med 2010;17:40-4. Crossref

27. Santos MS, Silva CG, Neto BS, et al.

Clinical and epidemiological aspects of scorpionism in the world: a

systematic review. Wilderness Environ Med 2016;27:504-18. Crossref

28. Chippaux JP, Goyffon M. Epidemiology

of scorpionism: a global appraisal. Acta Trop 2008;107:71-9. Crossref

29. Kounis NG, Soufras GD. Scorpion

envenomation. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1558-9.

30. Sofer S, Shalev H, Weizman Z, Shahak

E, Gueron M. Acute pancreatitis in children following envenomation by the

yellow scorpion Leiurus quinquestriatus. Toxicon 1991;29:125-8.Crossref

31. Pipelzadeh MH, Jalali A, Taraz M,

Pourabbas R, Zaremirakabadi A. An epidemiological and a clinical study on

scorpionism by the Iranian scorpion Hemiscorpius lepturus. Toxicon

2007;50:984-92.Crossref

32. Bergman NJ. Scorpion sting in

Zimbabwe. S Afr Med J 1997;87:163-7.

33. Centre for Food Safety, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Scorpion stings and langsat. Food Safety Focus (16th Issue,

Nov 2007). Available from: http://www.cfs.gov.hk/english/

multimedia/multimedia_pub/multimedia_pub_fsf_16_04. html. Accessed 1 Jun

2017.

34. Agriculture, Fisheries and

Conservation Department, Hong Kong SAR Government. Protection of

Endangered Species of Animals and Plants Ordinance. Available from:

http://www.afcd.gov.hk/english/conservation/con_end/

con_end_reg/con_end_reg_ord/con_end_reg_ord.html. Accessed 1 Jun 2017.

35. Waggoner TL, Nishimoto JH, Eng J. Eye

injury from tarantula. J Am Optom Assoc 1997;68:188-90.

36. Belyea DA, Tuman DC, Ward TP, Babonis

TR. The red eye revisited: ophthalmia nodosa due to tarantula hairs. South

Med J 1998;91:565-7. Crossref

37. Blaikie AJ, Ellis J, Sanders R,

MacEwen CJ. Eye disease associated with handling pet tarantulas: three

case reports. BMJ 1997;314:1524-5. Crossref