Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:255–7 | Number 3, June 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj133971

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Acute appendicitis complicating Amyand’s hernia: imaging features and literature review

WK Tsang, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

KL Lee, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)2;

KF Tam, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)3;

SF Lee, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)3

1 Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong

Kong

2 Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Prince of Wales

Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

3 Department of Radiology, North District Hospital, Sheung Shui, Hong

Kong

Corresponding author: Dr WK Tsang (tsang_k@yahoo.com.hk)

Abstract

Acute appendicitis complicating Amyand’s hernia is

an extremely rare condition, in which the appendix

herniates into the inguinal sac and, subsequently,

gets inflamed. The condition is difficult to diagnose

clinically. Imaging is valuable for its diagnosis and

detection of the associated complications. In this

article, we will discuss the imaging features of acute

appendicitis complicating Amyand’s hernia and the

results of a literature review on the condition.

Introduction

Amyand’s hernia is a rare condition in which the

appendix herniates into the inguinal sac. It is most

commonly detected incidentally during hernia repair. Acute appendicitis in Amyand’s hernia occurs even

less frequently, and is difficult to diagnose clinically.

Imaging is valuable for its diagnosis and detection

of the associated complications. Here we report

our experience with this disease entity, its imaging

features, and the results of a literature review.

Case report

An 82-year-old man with unremarkable history

presented to the surgeons with fever and generalised

abdominal pain. On physical examination, he had a

temperature of 38.8°C, diffuse abdominal tenderness,

and a tender, irreducible right inguinal lump.

Laboratory tests revealed mildly elevated white

cell count. His supine abdominal radiography was

unremarkable. A provisional diagnosis of irreducible

right inguinal hernia was made. However, it was

atypical that the patient did not have symptoms or

signs suggestive of intestinal obstruction. Urgent

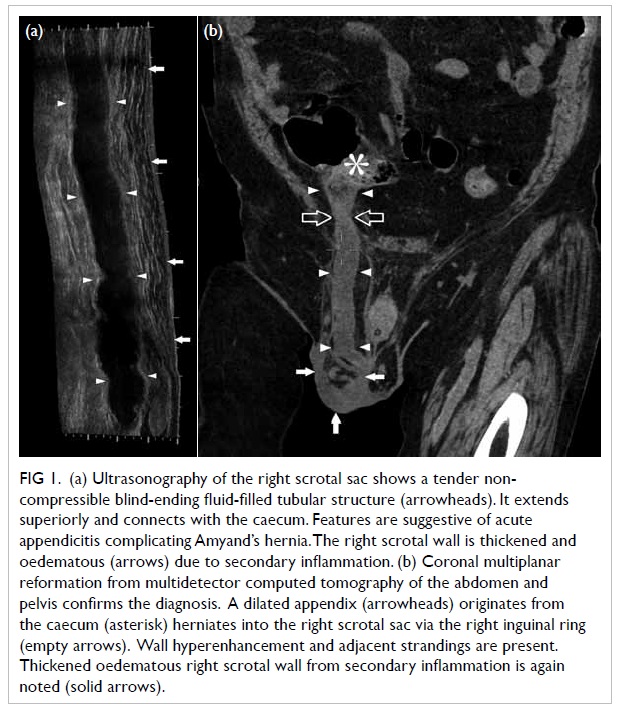

ultrasonography (USG) of the right groin showed a

blind-ending fluid-filled tubular structure within the

right scrotal sac. This structure extended superiorly

along the inguinal canal, entered the right lower

abdomen and joined the caecum (Fig 1a). It was

compatible with the appendix. Acute inflammation

was indicated by wall hypervascularity and tenderness

elicited upon compression. There was no

adjacent free fluid or collection to suggest abscess

formation or a ruptured appendix. The diagnosis

was confirmed by computed tomography (CT)

as dilated appendix with wall hyperenhancement

and herniation into the right scrotal sac (Fig 1b).

Periappendiceal strandings, reactive regional lymph

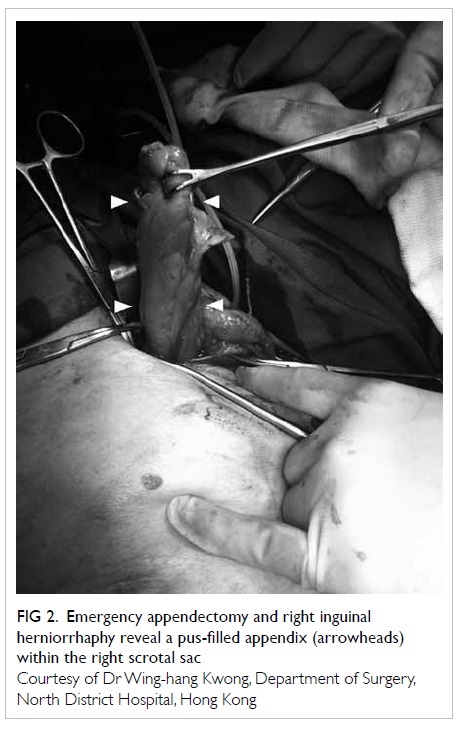

nodes, and oedematous right scrotal wall were noted. Emergency appendectomy and right inguinal

herniorrhaphy were performed. A pus-filled

appendix was revealed within the right scrotal sac

during the procedure (Fig 2).

Figure 1. (a) Ultrasonography of the right scrotal sac shows a tender noncompressible blind-ending fluid-filled tubular structure (arrowheads). It extends superiorly and connects with the caecum. Features are suggestive of acute appendicitis complicating Amyand’s hernia. The right scrotal wall is thickened and oedematous (arrows) due to secondary inflammation. (b) Coronal multiplanar reformation from multidetector computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis confirms the diagnosis. A dilated appendix (arrowheads) originates from the caecum (asterisk) herniates into the right scrotal sac via the right inguinal ring (empty arrows). Wall hyperenhancement and adjacent strandings are present. Thickened oedematous right scrotal wall from secondary inflammation is again noted (solid arrows)

Figure 2. Emergency appendectomy and right inguinal herniorrhaphy reveal a pus-filled appendix (arrowheads) within the right scrotal sac

Discussion

Amyand’s hernia is named after Claudius Amyand

(1660-1735), a sergeant-surgeon to King George II of

England. In 1735, he performed the first documented

successful appendectomy on an 11-year-old boy who

had a perforated, acutely inflamed appendix within

the right scrotal sac.1 The appendix was perforated

by a previously swallowed pin, leading to formation

of an enterocutaneous fistula.

Amyand’s hernia is uncommon, with a

prevalence of 1% among all the repaired inguinal

hernias.2 Most often, it is found incidentally during

surgery.2 It is more frequent in males. The condition

may present in individuals from any age, through

premature neonates to the elderly people.3 4 The

majority of cases occur on the right side, the side

where appendix normally locates and inguinal hernia

more commonly happens. Less than 10 cases of

left-sided Amyand’s hernia have been reported in

the literature; these can occur in patients with situs

inversus, intestinal malrotation, or a mobile caecum.5 6 7 8 9

Appendicitis more frequently occurs in

Amyand’s hernia than in appendix at normal

position. The superficial location of the appendix

within the inguinal sac can possibly make it more

vulnerable to trauma and secondary inflammation.

Another postulation is that the abdominal muscles

can constrict the hernial orifice and induce

intermittent compression of the appendix. This might

induce ischaemia of the appendix and make it more

susceptible to infection.10 Apart from appendicitis,

the other documented complications of Amyand’s

hernia include irreducibility and strangulation of

the appendix, abscess formation, peritonitis, and

enterocutaneous fistula formation.1 Other intra-abdominal

structures such as the caecum, urinary

bladder, and omentum can accompany the appendix

and herniate into the hernial sac.6 7

The diagnosis of Amyand’s hernia is rarely

made clinically. Most often it is mistaken as an

irreducible inguinal hernia. Imaging is valuable

for preoperative diagnosis and detection of any

complications. Coronal multiplanar reformations

from multidetector CT of the abdomen and pelvis

are excellent imaging modalities for demonstrating

a blind-ending tubular structure arising from the

caecum which extends into the inguinal sac. Luminal

dilatation, wall thickening and hyperenhancement,

adjacent stranding and fluid are suggestive of acute

appendicitis. Complications such as perforation and

abscess formation should be sought. In children and

pregnant women, USG and magnetic resonance

imaging are preferred with the advantage of being

radiation free. In USG, the acutely inflamed

appendix appears dilated, non-compressible with

thickened hypervascular wall, and is tender upon

compression.11 12 Sometimes the connection between

the appendix and caecum might not be readily

demonstrable, especially in overweight and pregnant

patients.

The differentiation between usual inguinal

hernias and Amyand’s hernia can be readily made

by imaging. In usual inguinal hernia, a segment of

small or large bowel is seen within the hernial sac.

Littre’s hernia, which is defined as herniation of

Meckel’s diverticulum, can mimic Amyand’s hernia

both clinically and radiologically. It occurs in 11% of patients with Meckel’s diverticulum. Similar to

Amyand’s hernia, Littre’s hernia is more prevalent in

males and on the right side.13 About 50% of the cases

occur in the inguinal region, with 20% occurring

in the femoral canal, and 20% in the umbilicus.14

Just like Amyand’s hernia, a blind-ending tubular

structure can be found in Littre’s hernia. Instead

of arising from the caecum, it originates from the

antimesenteric border of the distal small bowel.15

In addition, a normal appendix should be detected

in patients with Littre’s hernia unless it has been

resected.

Conclusion

Acute appendicitis complicating Amyand’s hernia is

extremely rare and is difficult to diagnose clinically.

Imaging is valuable for its diagnosis and detection of

associated complications.

References

1. Amyand C. Of an inguinal rupture, with a pin in the appendix caeci, incrusted with stone; and some observations on wounds in the guts. Phil Trans R Soc Lond 1736;39:329-36. CrossRef

2. Psarras K, Lalountas M, Baltatzis M, et al. Amyand's hernia—a vermiform appendix presenting in an inguinal hernia: a case series. J Med Case Rep 2011;5:463. CrossRef

3. Livaditi E, Mavridis G, Christopoulos-Geroulanos G. Amyand's hernia in premature neonates: report of two cases. Hernia 2007;11:547-9. CrossRef

4. Yang W, Tao Z, Chen H, et al. Amyand's hernia in elderly patients: diagnostic, anesthetic, and perioperative considerations. J Invest Surg 2009;22:426-9. CrossRef

5. Bakhshi GD, Bhandarwar AH, Govila AA. Acute appendicitis in left scrotum. Indian J Gastroenterol 2004;23:195.

6. Ghafouri A, Anbara T, Foroutankia R. A rare case report of appendix and cecum in the sac of left inguinal hernia (left Amyand's hernia). Med J Islam Repub Iran 2012;26:94-5.

7. Ravishankaran P, Mohan G, Srinivasan A, Ravindran G, Ramalingam A. Left sided Amyand's hernia, a rare occurrence: a case report. Indian J Surg 2013;75:247-8. CrossRef

8. Khan RA, Wahab S, Ghani I. Left-sided strangulated Amyand's hernia presenting as testicular torsion in an infant. Hernia 2011;15:83-4. CrossRef

9. Singh K, Singh RR, Kaur S. Amyand's hernia. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2011;16:171-2. CrossRef

10. Abu-Dalu J, Urca I. Incarcerated inguinal hernia with a perforated appendix and periappendicular abscess: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 1972;15:464-5. CrossRef

11. Akfirat M, Kazez A, Serhatlioğlu S. Preoperative sonographic diagnosis of sliding appendiceal inguinal hernia. J Clin Ultrasound 1999;27:156-8. CrossRef

12. Celik A, Ergün O, Ozbek SS, Dökümcü Z, Balik E. Sliding appendiceal inguinal hernia: preoperative sonographic diagnosis. J Clin Ultrasound 2003;31:156-8. CrossRef

13. Shahid N, Ibrahim K. Littre's hernia. Professional Med J 2005;12:479-81.

14. Fa-Si-Oen PR, Roumen RM, Croiset van Uchelen FA. Complications and management of Meckel’s diverticulum: a review. Eur J Surg 1999;165:674-8. CrossRef

15. Sinha R. Bowel obstruction due to Littre hernia: CT diagnosis. Abdom Imaging 2005;30:682-4. CrossRef