Hong Kong Med J 2015 Aug;21(4):318–26 | Epub 17 Jul 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144492

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Immigrants and tuberculosis in Hong Kong

CC Leung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine);

CK Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine);

KC Chang, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine);

WS Law, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine);

SN Lee, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine);

LB Tai, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine);

Eric CC Leung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine);

CM Tam, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)

Tuberculosis and Chest Service, Department of Health, Wanchai Chest Clinic, 1/F, 99 Kennedy Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CC Leung (cc_leung@dh.gov.hk)

Abstract

Objective: To examine the impact of immigrant

populations on the epidemiology of tuberculosis in

Hong Kong.

Design: Longitudinal cohort study.

Setting: Hong Kong.

Participants: Socio-demographic and disease

characteristics of all tuberculosis notifications in

2006 were captured from the statutory tuberculosis

registry and central tuberculosis reference

laboratory. Using 2006 By-census population data,

indirect sex- and age-standardised incidence

ratios by place of birth were calculated. Treatment

outcome at 12 months was ascertained from

government tuberculosis programme record forms,

and tuberculosis relapse was tracked through the

notification registry and death registry up to 30 June

2013.

Results: Moderately higher sex- and age-standardised

incidence ratios were observed among

various immigrant groups: 1.06 (Mainland China),

2.02 (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh), 1.59 (Philippines,

Thailand, Indonesia, Nepal), and 3.11 (Vietnam).

Recent Mainland migrants had a lower sex- and

age-standardised incidence ratio (0.51 vs 1.09) than

those who immigrated 7 years ago or earlier. Age

younger than 65 years, birth in the Mainland or

the above Asian countries, and previous treatment

were independently associated with resistance to

isoniazid and/or rifampicin. Older age, birth in the

above Asian countries, non-permanent residents,

previous history of treatment, and resistance to

isoniazid and/or rifampicin were independently

associated with poor treatment outcome (other than

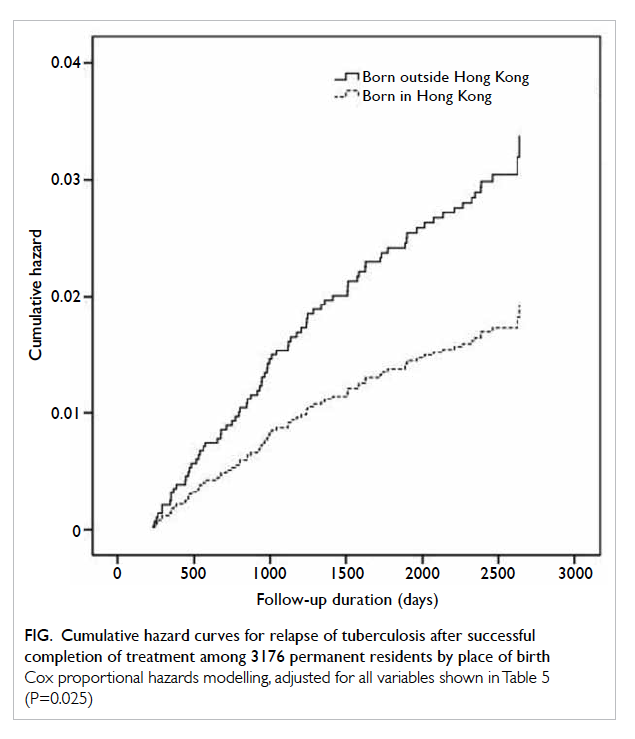

cure/treatment completion) at 1 year. Birth outside

Hong Kong was an independent predictor of relapse following successful

completion of treatment (adjusted

hazard ratio=1.76; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-2.89; P=0.025).

Conclusion: Immigrants carry with them a higher

tuberculosis incidence and/or drug resistance rate

from their place of origin. The higher drug resistance

rate, poorer treatment outcome, and excess relapse

risk raise concern over secondary transmission of

drug-resistant tuberculosis within the local community.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Immigrants carry with them a higher tuberculosis incidence and/or drug resistance rate from their place of origin to Hong Kong.

- Their higher drug resistance rate, poorer treatment outcome, and excess relapse risk may increase the risk of secondary transmission of drug-resistant tuberculosis within the local community.

Introduction

Great disparity in tuberculosis (TB) rates has been

reported in different parts of the world.1 Patients

with TB from 22 high-burden areas accounted

for over 80% of all notified TB cases in the world.1

Immigrants from these high-burden areas have often

been blamed for their impact on the TB situation

in many developed areas.2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 A rapid increase in

population was observed in Hong Kong in the last

century, largely due to a heavy influx of immigrants

from Mainland China.13 14 15 Despite remarkable

socio-economic improvement over the past four

decades, TB remains a common disease in Hong

Kong. In 2006, the TB notification rate remained as

high as 84.1/100 000.16 With continuing population

movement between the Mainland and Hong Kong,

there has been major concern about cross-border

transmission of infections including TB.

A large-scale population census has been

conducted in Hong Kong every 10 years since

1961, with a smaller by-census in-between.

Tuberculosis is a statutorily notifiable disease, and

basic demographic, clinical, and bacteriological

data of notified cases are regularly captured by the

TB notification registry. All residents are issued an

identity card, and the identity card is used by both

the TB notification registry and death registry as a

unique personal identifier. Eighteen government

chest clinics offer free programmatic case-finding

and treatment services for TB patients under a

centralised Tuberculosis and Chest Service of the

Department of Health, with estimated programme

coverage of over 80% of the population. Sputum

culture and drug susceptibility testing are regularly

performed by a centralised laboratory that is a

Supranational Reference Laboratory within the

World Health Organization/International Union

Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (WHO/IUATLD) network. Standard short-course regimens

are used in line with the WHO recommendations.

Patients are regularly followed up for 2 years after

initiation of TB treatment to facilitate cohort analysis

of treatment outcome. Using regularly captured

data within the statutory registries and government

TB programme, a longitudinal cohort study was

performed to examine the impact of immigrant

populations on the epidemiology of TB in Hong

Kong.

Methods

Data on sex, age, place of birth, residency status,

case category (new or retreatment), disease form

(pulmonary with or without extrapulmonary

involvement, or extrapulmonary only), sputum

smear and culture results of consecutive patients

notified within 2006 were obtained from the

territory-wide TB notification registry of Hong

Kong. An active case of TB was defined as positive

isolation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex or,

in the case of absent bacteriological confirmation,

disease diagnosed on clinical, radiological, and/or

histological grounds together with an appropriate

response to anti-TB treatment. As part of the public

health surveillance, bacteriological results of notified

cases were verified with the reports from the central

TB reference laboratory, with drug susceptibility test

results for streptomycin, isoniazid, rifampicin, and

ethambutol retrieved for culture-positive cases.

The sex- and age-stratified population data

were obtained from the 2006 By-census for the

following places of birth: Hong Kong (Group I);

Mainland China (Group II); India, Pakistan, and

Bangladesh (Indian subcontinent: Group III);

Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, and Nepal (other

key Asian minority groups, Group IV); Vietnam

(Group V); and other miscellaneous places of birth

(Group VI).17 The crude incidence of TB among

each of the above population groups was calculated

with adjustment made by a multiplication factor

(total notified cases / [total notified cases – cases

with missing place of birth]) for cases with missing

data on place of birth. The sex- and age-specific

(by 5-year age-group) TB rates were derived from

the overall population data and applied

to the corresponding sex-age groups of each of the

above six population groups to obtain the expected

number of cases. The observed number of TB cases

for each population group was compared with the

respective number of expected cases to obtain the

indirectly standardised TB incidence ratio. The

95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by

assuming a Poisson distribution in the occurrence of

events. For those born in Mainland China, further

stratification was made by the duration of residence

in Hong Kong.

The treatment outcome 12 months after

initiation of treatment was ascertained for those

patients being managed by the government chest

clinics under the Tuberculosis and Chest Service

from the programme record form of the Tuberculosis

and Chest Service. Treatment success was defined

as cure or treatment completion (successfully

completed treatment of ≥6 months for new cases and

≥8 months for retreatment cases), irrespective of

subsequent relapse or death or loss to follow-up. All

other treatment outcomes (including death before

treatment completion, default, transferring out, still

on treatment at 12 months after treatment initiation)

were regarded as unsuccessful. Permanent residents

who successfully completed treatment under the

government TB programme were subsequently

tracked up to 30 June 2013 through the territory-wide

TB notification registry and death registry for

relapse of TB or death.

Chi squared and Fisher’s exact tests were used

as appropriate for categorical variables and analysis

of variance was used for continuous variables.

Logistic regression modelling was used for multivariate

analysis of 12-month outcome. For censored data of

TB relapse during follow-up, Kaplan-Meier analysis

was used in univariate analysis and Cox proportional

hazards modelling was used in multivariate analysis

to adjust for potential confounders. A two-tailed P

value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The study was part of a public health

surveillance exercise in tracking the profile and

outcome of statutory TB notifications. It did not

involve intervention on human subjects.

Results

A total of 6246 TB notifications were received

in 2006, 480 of which were excluded because of

duplicate notification or revised diagnosis, leaving

5766 cases in the 2006 TB notification registry.

Of these, 18 cases involving tourists, 17 cases

involving illegal immigrants, and 329 cases without

information on place of birth were also excluded,

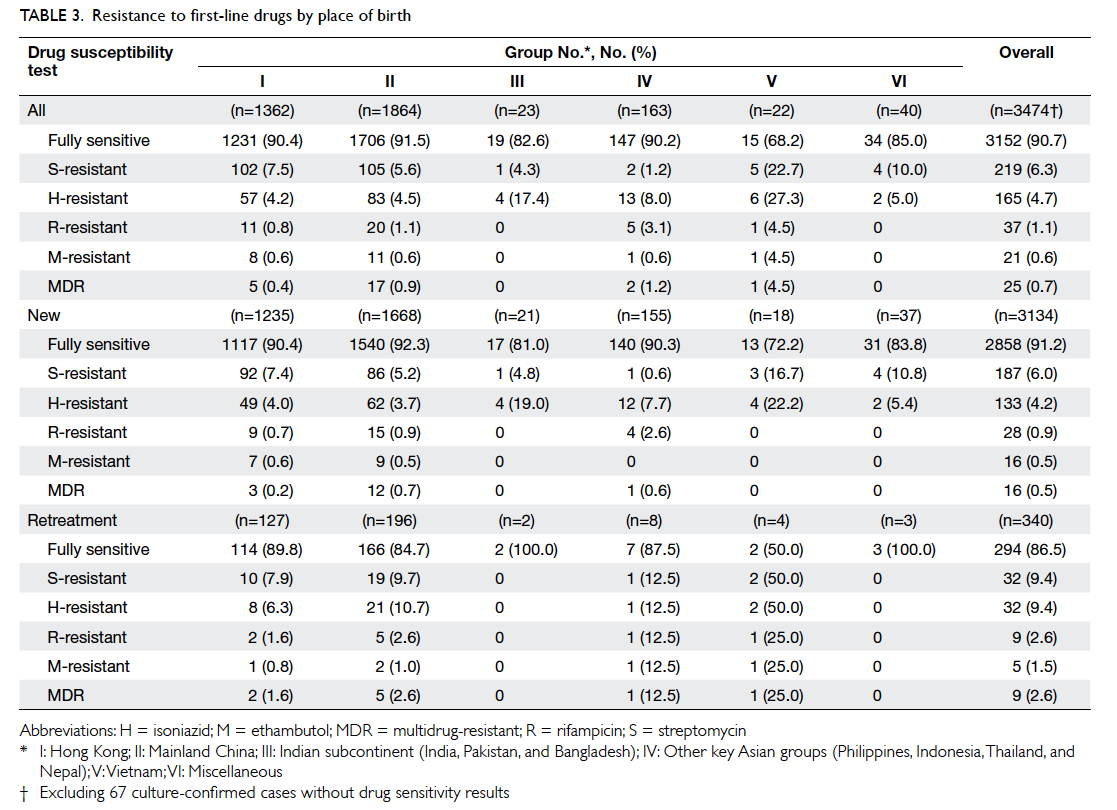

leaving 5402 cases for analysis. Table 1 shows their

basic characteristics as stratified by place of birth.

The vast majority (92.3%) of TB cases involved

residents born in either Hong Kong or Mainland

China. Significant differences were observed

between the six population groups in terms of sex

and age distribution as well as proportions of new

and pulmonary cases, but not proportions of either

smear-positive or culture-confirmed cases.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of tuberculosis cases notified in 2006 in Hong Kong as stratified by place of birth

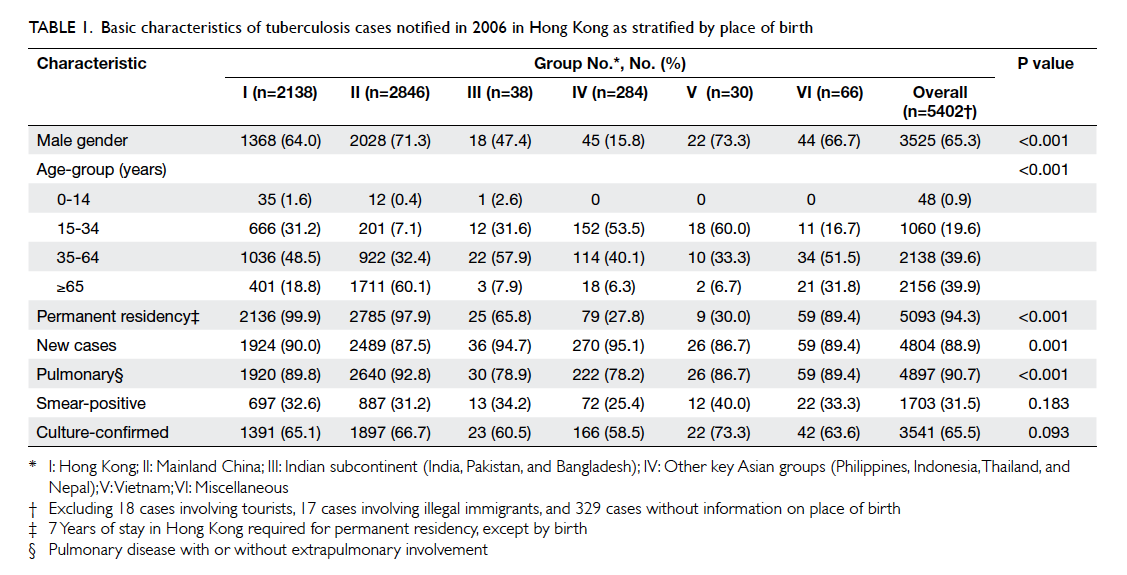

Table 2 summarises the incidence of TB and

indirectly sex- and age-standardised incidence

ratio (SIR) of TB for the six population groups. The TB SIR was significantly above 1 for

those born in Mainland China (males and combined),

Group III (females and combined), Group IV

(females and combined), and Group V (males and

combined), but significantly below 1 for those born

in Hong Kong (males, females, and combined) and

other miscellaneous places of birth (males, females,

and combined). Mainland-born permanent residents

(staying in Hong Kong for ≥7 years) maintained a

higher TB risk than the population average for both

sexes and combined. Nonetheless, recent Mainland

immigrants with duration of stay of less than 7

years actually had a lower TB risk than the general

population, despite sex and age standardisation.

Table 2. Annual incidences of active tuberculosis (all forms) in resident population by place of birth in 2006

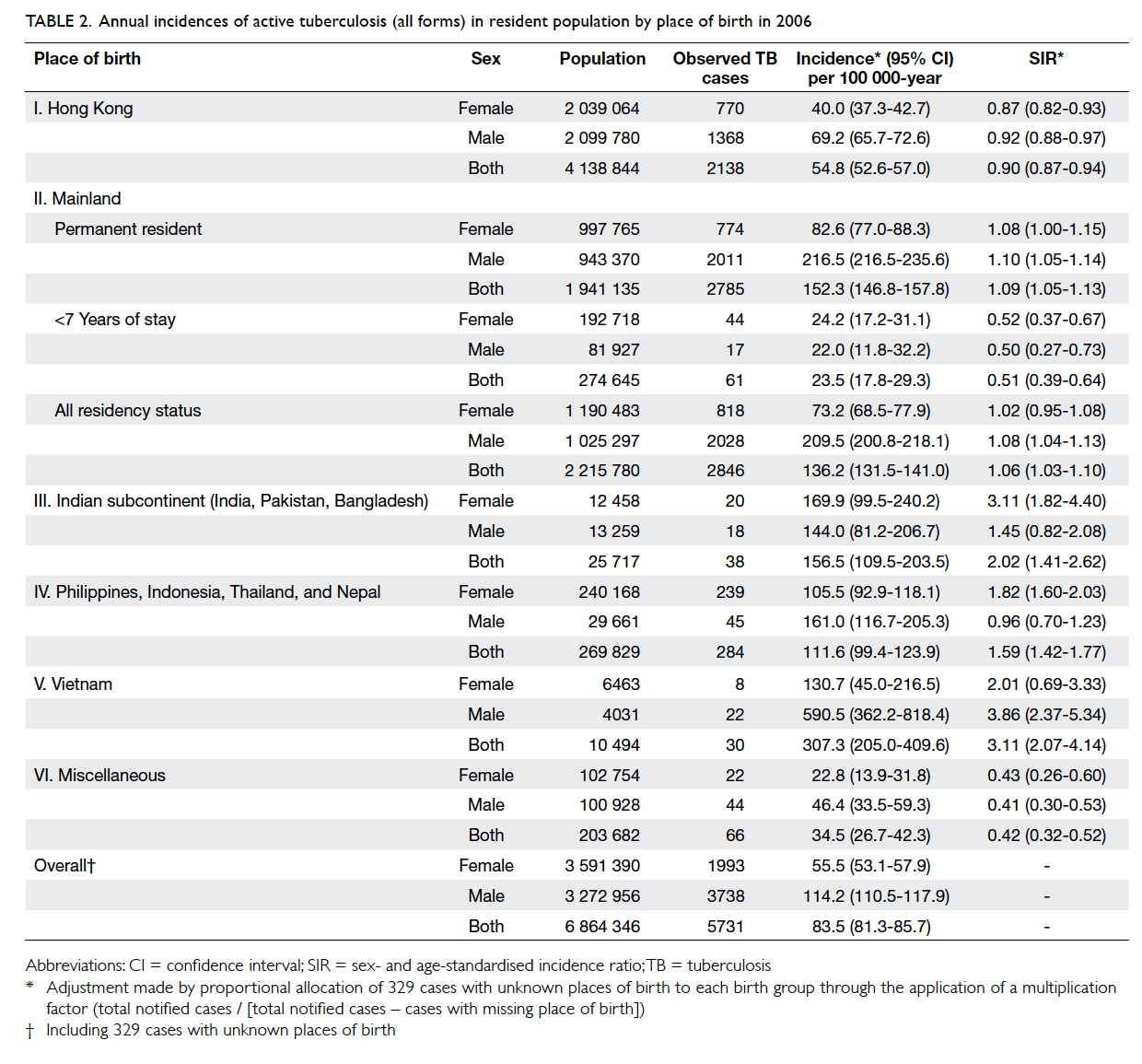

Table 3 shows the resistance profile of 3474 (98.1%) culture-confirmed

cases (with available drug susceptibility testing results) by place of birth. Table 4 summarises

the results of univariate and multiple logistic

analyses with respect to isoniazid, rifampicin, and

multidrug resistance (resistance to both isoniazid

and rifampicin) of 3434 culture-confirmed cases

after combining all patients born in Asian countries

listed under Groups III, IV and V, and excluding 40

patients with miscellaneous places of birth in Group

VI that included very few drug-resistant cases. In the

multiple logistic regression models using a backward

stepwise elimination approach, only age <65 years,

place of birth, and history of previous treatment

(ie retreatment cases) remained important

independent predictors of isoniazid, rifampicin, and

multidrug resistance.

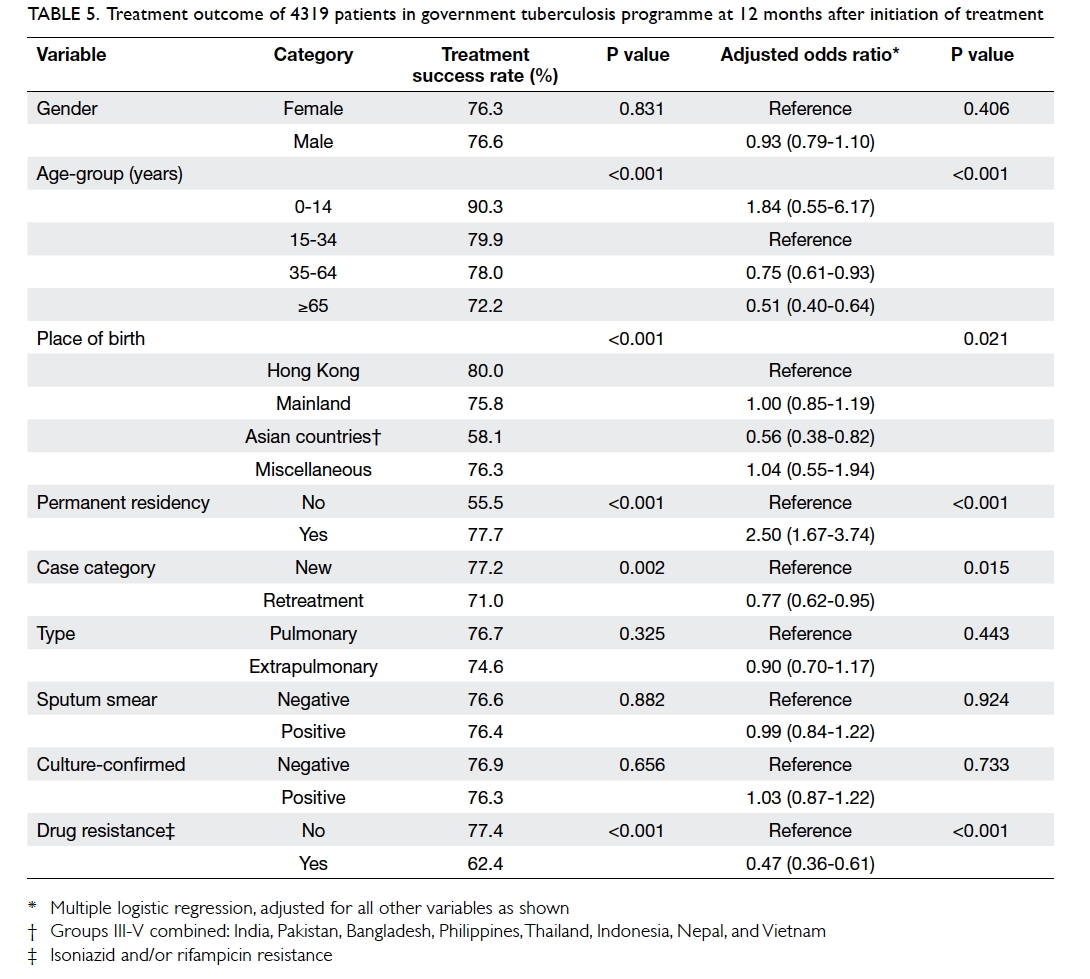

Of the 5402 subjects included in this study, 4319

(80.0%) were managed, at least at some stage of the

disease, within the government TB programme. A

total of 3304 (76.5%) patients successfully completed

treatment within 12 months after initiation of

treatment. Table 5 summarises the factors associated

with 12-month treatment outcome in both univariate

analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Of those patients who successfully completed

treatment, 3176 (96.1%) permanent residents in

Hong Kong were followed up by cross-linking with

the TB notification registry and death registry until

relapse of TB, death or 30 June 2013, whichever was

the earliest. After a mean (± standard deviation)

duration of 5.28 ± 1.64 years of follow-up, 80 (2.5%)

relapses were detected at a median (range) time

interval of 1004 (225-2640) days after initiation of

treatment, 37 (46.3%) of which were bacteriologically

confirmed. In Kaplan-Meier analysis, the relapse risk

was higher among permanent residents born outside

Hong Kong than among those born in Hong Kong

(3.0% vs 1.9%; log rank test, P=0.019). A consistently

higher relapse risk was present among those born

outside Hong Kong (adjusted hazard ratio=1.76; 95%

CI, 1.07-2.89; P=0.025) after adjustment for gender,

age, case category (new or retreatment), type of

TB (pulmonary or extrapulmonary only), sputum

smear, culture, and drug resistance to isoniazid and/or rifampicin at the baseline. The Figure shows the

cumulative hazard curves by place of birth in and

outside Hong Kong in Cox proportional hazards

modelling.

Table 5. Treatment outcome of 4319 patients in government tuberculosis programme at 12 months after initiation of treatment

Figure. Cumulative hazard curves for relapse of tuberculosis after successful completion of treatment among 3176 permanent residents by place of birth

Cox proportional hazards modelling, adjusted for all variables shown in Table 5 (P=0.025)

Discussion

In this study, persons born in Hong Kong had a SIR of

0.90 (95% CI, 0.87-0.94), while those born in Mainland

China (Group II), Indian subcontinent (Group III),

Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Nepal (Group IV),

and Vietnam (Group V) had significantly higher

SIRs of 1.06, 2.02, 1.59, and 3.11 respectively (Table

2). Recent Mainland migrants (with length of stay <7

years), however, had a significantly lower SIR (0.51

vs 1.09) than other Mainland-born residents. Age

<65 years, birth in Mainland or Groups III-V Asian

countries, and history of previous treatment were

independently associated with resistance to isoniazid

and/or rifampicin (Table 4). Older age, birth in Groups

III-V Asian countries, non-permanent residents,

retreatment case, and resistance to isoniazid and/or

rifampicin were independently associated with lower

treatment success (cure/treatment completion) rate at

1 year (Table 5). Birth outside Hong Kong (Groups II-V combined) was an independent predictor of TB

relapse among permanent residents after successful

treatment completion under the government TB

programme (Fig).

With the successful control of recent

transmission of TB in Hong Kong, the majority of

TB cases arose from endogenous reactivation of

past infection.18 The higher SIR and drug resistance

prevalence among Mainland immigrants and

immigrants from Groups III-V Asia countries

corroborate reports of higher TB incidence2 3 4 5 6 8 and drug resistance7 12 among immigrants in low-TB-burden countries. These higher risks among

immigrants may have resulted at least in part from

reactivation of latent TB infection9 10 11 acquired

during their previous residence in, and/or travel to,

their places of birth with higher burdens of TB and/or drug resistance.1 19 20 21 22 Apart from possible selection

factors in migration, the progressive fall in TB

prevalence in the Mainland over the recent decades22

could also have contributed to a lower burden of

latent TB infection, and hence SIR, among recent

Mainland immigrants compared with those who

immigrated longer ago. Taking into consideration

the independent effects of birth outside Hong Kong

on both treatment outcome and relapse (Table 5

and Fig), population mobility may have adversely

affected treatment adherence, and thus impacted

on treatment outcome and/or relapse with possible

acquisition of drug resistance. In line with these

observations, a previous case-control study also

identified younger age, non-permanent residents,

and frequent travel as independent predictors of

multidrug-resistant TB among previously treated

patients in Hong Kong.23

Although this study showed an increased risk

of TB among immigrants in Hong Kong, which is a

metropolitan city with intermediate TB burden, the

vast majority of TB cases still occurred among the

majority population groups of local-born persons or

permanent residents born in Mainland China (both

of which were largely of Chinese ethnicity). This is

contrary to the situation in most low-burden areas,

where the majority of TB cases often came from

foreign-born minority groups.2 3 12 The relatively high

crude TB incidence rate of 55/100 000, even among

the local-born (both genders combined) in this intermediate burden area

(Table 2), could have reduced the risk differential

between the immigrant groups and the local-born,

thus reducing the influence of immigrants on the

overall TB incidence. Nonetheless, the higher drug

resistance rate, poorer treatment outcome, and

higher relapse rate among immigrants in this study

remain critical areas of concern. In a recent study

on the transmission of drug-resistant TB in Hong

Kong,24 46% of all multidrug-resistant TB cases were

new cases with no previous history of treatment.

This suggests ongoing transmission of these difficult-to-treat TB cases within our community. The degree

of molecular clustering was as high as 65% among

extensively drug-resistant TB cases, the majority of

which did not have obvious epidemiological linkage,

suggesting active transmission outside households

or other conventional close contact settings.24

This study was based on territory-wide data

from by-census, statutory registries, a centralised

government TB programme, and centralised

TB laboratory. The well-developed health care

infrastructure in Hong Kong with easy access to

free TB care services allowed capture of relevant

information from TB patients notified in a by-census

year and successful tracking of the majority

of them for treatment outcome and relapse. Some

degree of incomplete case ascertainment was still

likely as in all other public health surveillance

systems. Even though around 20% of the notified

patients were managed outside the government

TB programme, this might not have substantially

confounded the internal comparisons among

different population groups if access to care could be

assumed to be roughly parallel. If the usual inverse

care law25 did apply, the direction of bias would

likely be underestimation of the risks among the

immigrants as an underprivileged group. With the

limited amount of socio-demographic and clinical

information contained in the various statutory

registries and programme forms, this study may

not be in a strong position to analyse the complex

mechanisms that underlie the observed associations

between immigrants and treatment outcome or

relapse. Further studies are therefore warranted to

identify potential areas of intervention for specific

minority groups.

Declaration

No external grant or support has been received for

this study.

References

1. Global tuberculosis control report 2013. WHO/HTM/TB/2013.11. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/91355/1/9789241564656_eng.pdf.

Accessed May 2015.

2. Gilbert RL, Antoine D, French CE, Abubakar I, Watson JM,

Jones JA. The impact of immigration on tuberculosis rates

in the United Kingdom compared with other European

countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009;13:645-51.

3. Das D, Baker M, Venugopal K, McAllister S. Why the

tuberculosis incidence rate is not falling in New Zealand.

N Z Med J 2006;119:U2248.

4. Cain KP, Haley CA, Armstrong LR, et al. Tuberculosis

among foreign-born persons in the United States:

achieving tuberculosis elimination. Am J Respir Crit Care

Med 2007;175:75-9. Crossref

5. Dye C, Lönnroth K, Jaramillo E, Williams BG, Raviglione

M. Trends in tuberculosis incidence and their determinants

in 134 countries. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:683-91. Crossref

6. Svensson E, Millet J, Lindqvist A, et al. Impact of

immigration on tuberculosis epidemiology in a low-incidence

country. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011;17:881-7. Crossref

7. Baussano I, Mercadante S, Pareek M, Lalvani A, Bugiani

M. High rates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis among

socially marginalized immigrants in low-incidence area,

1991-2010, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19:1437-45. Crossref

8. Manangan L, Elmore K, Lewis B, et al. Disparities in

tuberculosis between Asian/Pacific Islanders and non-Hispanic Whites, United States, 1993-2006. Int J Tuberc

Lung Dis 2009;13:1077-85.

9. Farah MG, Meyer HE, Selmer R, Heldal E, Bjune G. Long-term

risk of tuberculosis among immigrants in Norway. Int

J Epidemiol 2005;34:1005-11. Crossref

10. Patel S, Parsyan AE, Gunn J, et al. Risk of progression to

active tuberculosis among foreign-born persons with

latent tuberculosis. Chest 2007;131:1811-6. Crossref

11. McPherson ME, Kelly H, Patel MS, Leslie D. Persistent

risk of tuberculosis in migrants a decade after arrival in

Australia. Med J Aust 2008;188:528-31.

12. Long R, Langlois-Klassen D. Increase in multidrug-resistant

tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in Alberta among foreign-born

persons: implications for tuberculosis management.

Can J Public Health 2013;104:e22-7.

13. Tuberculosis and Chest Service. Annual Report of

Tuberculosis and Chest Service 1949. Hong Kong:

Department of Health; 1950: 3.

14. Tuberculosis and Chest Service. Annual Report of

Tuberculosis and Chest Service 1961. Hong Kong:

Department of Health; 1962: 3.

15. Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics April 2012, p.9.

Available from: http://www.census2011.gov.hk/pdf/Feature_articles/Trends_Pop_DH.pdf. Accessed 3 Jul 2013.

16. Tuberculosis and Chest Service. Annual Report of

Tuberculosis and Chest Service 2006. Hong Kong: Department of Health; 2008.

17. Census and Social Statistics Department of Hong Kong,

2006 Population By-census. Available from: http://www.bycensus2006.gov.hk/en/data/data2/index.htm. Accessed

3 Jul 2014.

18. Chan-Yeung M, Kam KM, Leung CC, et al. Population-based

prospective molecular and conventional

epidemiological study of tuberculosis in Hong Kong.

Respirology 2006;11:442-8. Crossref

19. Zignol M, van Gemert W, Falzon D, et al. Surveillance of

anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the world: an updated

analysis, 2007-2010. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:111-119D. Crossref

20. Zhao Y, Xu S, Wang L, et al. National survey of drug-resistant

tuberculosis in China. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2161-70. Crossref

21. Udwadia ZF, Amale RA, Ajbani KK, Rodrigues C. Totally

drug-resistant tuberculosis in India. Clin Infect Dis

2012;54:579-81. Crossref

22. Wang L, Zhang H, Ruan Y, et al. Tuberculosis prevalence

in China, 1990-2010; a longitudinal analysis of national

survey data. Lancet 2014;383:2057-64. Crossref

23. Law WS, Yew WW, Leung CC, et al. Risk factors for

multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Hong Kong. Int J

Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:1065-70.

24. Leung EC, Leung CC, Kam KM, et al. Transmission

of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant

tuberculosis in a metropolitan city. Eur Respir J

2013;41:901-8. Crossref

25. Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971;1:405-12. Crossref