Hong Kong Med J 2015 Oct;21(5):389–93 | Epub 31 Jul 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144481

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Paracetamol overdose in Hong Kong: is the 150-treatment line good enough to cover patients

with paracetamol-induced liver injury?

Simon TB Chan, MB, BS1;

CK Chan, Dip Clin Tox, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)2;

ML Tse, FHKCEM, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)2

1 Department of Accident and Emergency, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

2 Hong Kong Poison Information Centre, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Simon TB Chan (ctb021@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the failure rate of the

150-treatment line for paracetamol overdose in Hong

Kong, and the impact if the treatment threshold was

lowered.

Design: Case series.

Setting: Public hospitals, Hong Kong.

Patients: All patients with acute paracetamol

overdose reported to the Hong Kong Poison

Information Centre from 1 January 2011 to 31

December 2013 were studied and analysed for

the timed serum paracetamol concentration and

their relationship to different treatment lines. Presence

of significant liver injury following paracetamol

overdose was documented. The potential financial

burden of different treatment lines implemented

locally was estimated.

Results: Of 893 patients, 187 (20.9%)

had serum paracetamol concentration above

the 150-treatment line, 112 (12.5%) had serum

paracetamol concentration between the 100- and 150-treatment lines, and 594 (66.5%) had

serum paracetamol level below the 100-treatment

line. Of the 25 (2.8%) patients who developed

significant liver injury, two were between the 100- and 150-treatment lines, and the other two were

below the 100-treatment line. The failure rate of

the 150-treatment line was 0.45%. Lowering the

treatment threshold to the 100-treatment line might

lower the failure rate of the treatment nomogram

to 0.22% but approximately 37 more patients per

year would need to be treated. It would incur an

additional annual cost of HK$189 131 (US$24 248), and an

additional 1.83 anaphylactoid reactions per year. The

number needed-to-treat to potentially reduce one

significant liver injury is 112.

Conclusions: Lowering the treatment threshold of

paracetamol overdose may reduce the treatment-line failure rate. Nonetheless such a decision

must be balanced against the excess in treatment

complications and health care resources.

New knowledge added by this study

- For paracetamol overdose in Hong Kong, the failure rate of the 150-treatment line is 0.45%. Lowering the treatment threshold to 100-treatment line may lower the failure rate to 0.22%.

- Implementing the 100-treatment line in Hong Kong would incur an annual cost of HK$189 131 (US$24 248), 37 more patients per year needing treatment, and an additional 1.83 anaphylactoid reactions per year. The number needed-to-treat to potentially reduce one significant liver injury is 112.

- Clinicians should be aware of the chance of treatment-line failure in patients with acute paracetamol overdose.

- Recommendations for the treatment threshold for acute paracetamol overdose may be evaluated together with the clinical and financial impacts described in this study.

Introduction

Paracetamol is a common analgesic and antipyretic,

and is currently the most commonly overdosed

therapeutic agent in Hong Kong, accounting for 8.4%

of all poisoning cases.1 After the first human case

report of paracetamol-induced liver injury in 1966,2

paracetamol overdose remains an important cause

of acute liver failure with mortalities worldwide. The

efficacy of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) in the treatment

and prevention of paracetamol-induced liver injury

has been established over the last decades.3 4 In acute paracetamol overdose, serum paracetamol

concentration measured at 4 to 24 hours post-ingestion

(timed serum paracetamol concentration)

is plotted on the Rumack-Matthew nomogram.

Treatment with NAC should be initiated if the

serum paracetamol concentration is plotted on or

above the treatment line.5 Different treatment lines

exist, however, and there is no worldwide consensus

on the safest serum paracetamol concentration at

which to initiate NAC treatment.

In the United States, the timed serum

paracetamol concentration is plotted against a

single treatment line starting at 150 mg/L at 4 hours

post-ingestion (150-treatment line).6 Patients with

serum paracetamol concentration above this line

are treated with NAC. This line was imposed by the

United States Food and Drug Administration with a

25% safety margin based on the work of Rumack in

1975,5 and was also adopted in Australia and New

Zealand.7

Previously in the United Kingdom, two

different treatment lines were used. Patients were

categorised into ‘normal risk’ or ‘high risk’ according

to their medical and behavioural background.

Those patients with possible glutathione depletion,

for example with malnutrition or chronic heavy

alcoholism, were considered ‘high risk’ while the

remaining patients were considered ‘normal risk’.

Treatment lines starting at 200 mg/L (200-treatment

line) and 100 mg/L (100-treatment line) at 4 hours

post-ingestion were used in patients with ‘normal

risk’ and ‘high risk’, respectively.

The Medicines and Healthcare products

Regulatory Agency of the United Kingdom lowered

the threshold of NAC treatment in 2012,8 following a

series of patients with severe liver injury and several

mortalities after paracetamol overdose were reported

to have a serum paracetamol concentration below the

level dictated by the previous treatment protocol.9

All patients in the United Kingdom with serum

paracetamol concentration over the 100-treatment

line are now prescribed NAC treatment.

The Hong Kong Poison Information Centre

(HKPIC) currently recommends intravenous NAC

treatment in patients with serum paracetamol

concentration above the 150-treatment line. One

course of NAC treatment typically takes 21 hours

of intravenous infusion in hospital under close

observation. In this study, we examined a series

of non-staggered acute paracetamol overdose

cases in Hong Kong to determine how well the

current 150-treatment line can cover patients with

paracetamol-induced liver injury and the impact

on the local health care system if the treatment

threshold is changed.

Methods

We performed a retrospective observational study by

reviewing patients with acute paracetamol overdose

who presented to 16 emergency departments (EDs)

in public hospitals in Hong Kong between 1 January

2011 and 31 December 2013. Data were retrieved

from the electronic database of the HKPIC and

electronic Patient Record of the Hospital Authority.

All patients aged 12 years or above with acute

paracetamol overdose were included.

In this study, acute paracetamol overdose was

defined as ingestion of paracetamol or paracetamol-containing

medications in a single attempt. As some

patients intentionally took a large number of tablets,

we allowed a maximum duration of ingestion

process for up to 1 hour. When the ingestion process

occurred over 1 hour, the overdose was

considered to be staggered and such patients were

excluded from the study. Patients were also excluded

if time of ingestion was undetermined, no serum

paracetamol concentration was available within 4

to 24 hours post-ingestion, or patients presented to

EDs more than 24 hours post-ingestion.

The following data were collected: clinical

profile including age, sex, first serum paracetamol

concentration between 4 and 24 hours post-ingestion,

treatment given, and the presence of significant liver

injury during the episode. Significant liver injury was

defined as serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

level of ≥1000 IU/L in the absence of a known history

of deranged liver function.

Results

There were a total of 1243 patients with acute

paracetamol overdose within the study period.

Exclusions included 73 patients with staggered

overdose, 137 patients with undetermined time of

paracetamol ingestion, 100 patients with no serum

paracetamol concentration available within 4 to 24

hours of ingestion, and 40 patients who presented

to the EDs of >24 hours post-ingestion. Data on 893

patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were

analysed. The clinical data of the studied patients are

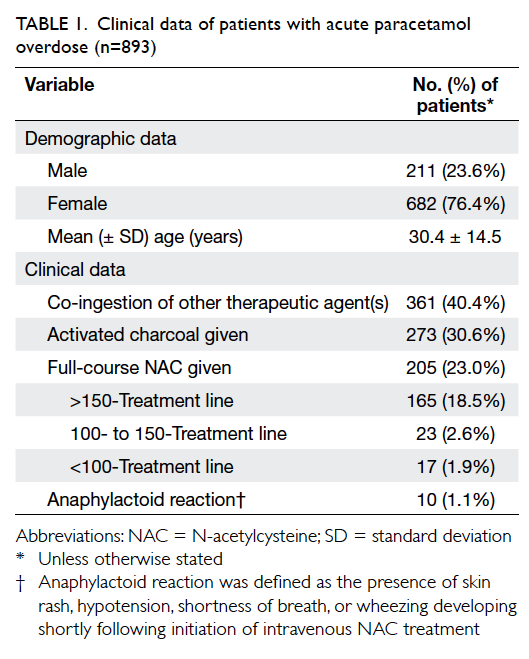

presented in Table 1.

No deaths occurred in the study population

and no patient required liver transplantation.

There were 187 (20.9%) patients with a serum

paracetamol concentration above the 150-treatment

line, 112 (12.5%) patients had a serum paracetamol

concentration between the 100- and 150-treatment

lines, and the remaining 594 (66.5%) patients

had serum paracetamol concentration below the

100-treatment line.

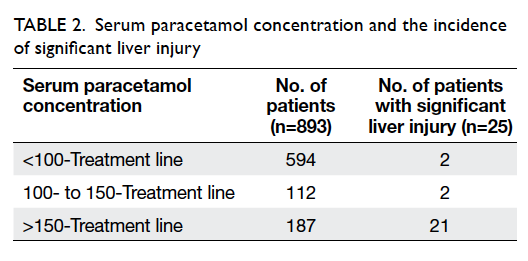

Significant liver injury occurred in 25 patients

within the study period, giving an overall incidence of 2.8% following acute paracetamol

overdose (Table 2). Four patients with

serum paracetamol concentration below the

150-treatment line developed significant liver injury.

The failure rate of the 150-treatment line was 0.45%

(4/893). If 100-treatment line is applied instead

of 150-treatment line, two patients with serum

paracetamol concentration below the 100-treatment

line developed significant liver injury. The failure

rate of the 100-treatment line would thus be 0.22%

(2/893).

Discussion

Paracetamol overdose is a commonly encountered

problem in Hong Kong, and is the single most

common cause of poisoning. According to the

Rumack-Matthew nomogram, a serum paracetamol

concentration starting from 200 mg/L at 4 hours

is associated with an increased risk of liver injury

and death.10 The clinical decision to commence

treatment with NAC is dictated by the timed serum

paracetamol concentration plotted against the

nomogram with a treatment line. If the timed serum

paracetamol concentration is above the treatment

line, NAC treatment is indicated. Based on different

considerations, for example the accuracy of clinical

history and individual susceptibility, different

treatment lines are applied by different countries or

centres to guide initiation of NAC treatment.

Since the United Kingdom lowered the NAC

treatment threshold to the 100-treatment line,8 there

has been discussion in Hong Kong about the benefit

of changing local recommendations. Nonetheless,

it is unknown whether the reasons for changing

the recommendation in the United Kingdom apply

to the Hong Kong population. This study serves to

provide more information for further discussion and

consideration.

We were most interested to identify patients

who developed significant liver injury following

paracetamol overdose in which the serum

paracetamol concentration was lower than the

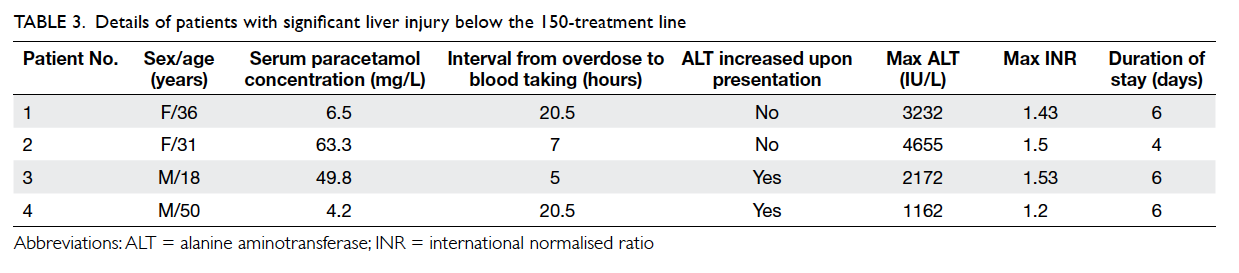

treatment line. In the 3-year study period, four

patients with a paracetamol concentration below

the 150-treatment line developed significant liver

injury. These cases are discussed in detail below and

summarised in Table 3.

Case 1

A 36-year-old woman with known depressive

disorder attended the ED 20.5 hours following

ingestion of 100 tablets of paracetamol. She had

abdominal pain afterwards. On presentation,

the paracetamol concentration was 43 µmol/L

(6.5 mg/L). This level falls between the 100- and

150-treatment lines. The level of ALT was 53 IU/L

and international normalised ratio (INR) was 1.03.

She was admitted to the medical ward. Although

her serum paracetamol concentration plotted below

the 150-treatment line, NAC treatment was given

soon after admission based on the clinical features

of hepatitis. Her liver enzyme level started to elevate

the next day with clinical jaundice, and on day 2 of

admission her ALT level peaked at 3232 IU/L, and

INR at 1.43 with bilirubin level of 45 µmol/L. She was

treated conservatively and liver function gradually

improved. She was discharged on day 6 of admission.

Case 2

A 31-year-old woman attempted suicide by ingesting

around 50 tablets of over-the-counter drugs. She was

brought to the ED 3 hours afterwards and complained

of mild dizziness and nausea. Activated charcoal

50 g was given and she was admitted to the Intensive

Care Unit (ICU). Serum paracetamol concentration

taken at 7 hours post-ingestion was 418 µmol/L

(63.3 mg/L), between the 100- and 150-treatment

lines. The patient was treated supportively in the

ICU for the first day. At 24-hour post-ingestion her

ALT level was 48 IU/L, INR was 1.3, and at 29 hours

post-ingestion the ALT level elevated to 73 IU/L,

with INR of 1.4. Intravenous NAC treatment was

commenced 30 hours post-ingestion. Liver function

continued to deteriorate: ALT level peaked at 4655 IU/L

and INR peaked at 1.5 on day 3 of admission. The

serum bilirubin level was 67 µmol/L. She had clinical

jaundice and vomiting. On day 4, NAC infusion was

stopped. She had full recovery of liver function at

1-month follow-up.

Case 3

An 18-year-old man ingested around 50 tablets of

paracetamol in a suicide attempt. He attended the ED

5 hours later. He was asymptomatic on presentation.

Serum paracetamol concentration at 5 hours post-ingestion

was 330 µmol/L (49.8 mg/L), below the

100-treatment line. At presentation his ALT level was 64 IU/L

and INR was 1.06. Liver function tests repeated

at 7 hours post-ingestion showed ALT level was

increased to 98 IU/L and INR was 1.3. Intravenous

NAC was started. The liver function deterioration

peaked at day 3 of admission with ALT level of

2172 IU/L and INR of 1.53 and the patient complained

of abdominal pain; NAC infusion was continued

until day 5 of admission. His liver function improved

and he was transferred to the psychiatric ward for

management of depression on day 6. He had full

recovery of his liver function.

Case 4

A 50-year-old man had flu-like symptoms and fever

for 5 days. He ingested 60 tablets of paracetamol in a

suicide attempt related to financial stress and physical

discomfort. At 20 hours after ingestion, he attended

the ED for recurring fever. On presentation his body

temperature was 40.2°C. Blood tests revealed ALT

level of 511 IU/L, INR of 1.1, and serum paracetamol

concentration of 28 µmol/L (4.2 mg/L), below the

100-treatment line at 20.5 hours; NAC treatment

was given based on the clinical features of chemical

hepatitis. His liver markers peaked the next day

with ALT level of 1162 IU/L, INR of 1.2, and with

abdominal pain. His fever and respiratory symptoms

subsided with a course of intravenous antibiotics.

His liver function gradually improved and he was

transferred to the psychiatric ward on day 6 after

admission.

All four patients were considered ‘normal risk’

according to the old United Kingdom classification

of treatment line options.

Analysis of these four cases revealed that if

the NAC treatment threshold had been lowered

from the 150-treatment line to 100-treatment line,

the treatment line would have covered the first two

cases but not the last two. The treatment-line failure

rate would thus be reduced by half to 0.22%. A lower

failure rate of the treatment line implies that people

who will develop liver injury following paracetamol

overdose are more likely to receive early treatment

with NAC. Although not proven in this study, this

should prevent a small number of cases of significant

morbidity related to severe paracetamol poisoning.

Giving intravenous NAC is not without risk,

however. If the 100-treatment line had been applied

instead of the 150-treatment line, the number of

patients in this study in whom NAC treatment would

have been indicated would increase from 187 (20.9%)

to 299 (33.5%)—an additional 112 courses of NAC

over 3 years. In addition, since 4.9% of the patients

given NAC in this study developed an anaphylactoid

reaction, there would also have been an additional

5.49 anaphylactoid reactions (1.83 patients/year).

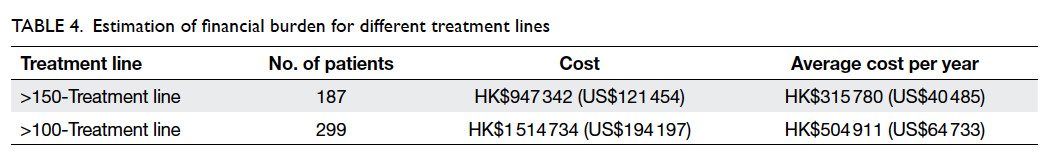

The financial burden of treating additional

patients with NAC courses can be estimated by

additional cost of hospital stay11 and drug cost

of NAC, approximately HK$5066 (US$650) per

standard 21-hour intravenous NAC administration.

This is similar to the estimated cost of a

standard NAC course in a United Kingdom study.12

An additional 112 courses of NAC would cost

HK$567 392 (US$72 743) within the study period of

3 years with an average of HK$189 131 (US$24 248)

per year. The calculations are shown in Table 4. On

rare occasions NAC treatment may be extended over

21 hours and result in a further increase in the actual

cost.

The liver injury in case 2 was judged to have

been preventable by timely NAC treatment in

nomogram perspective. Thus, we would need to

administer NAC to an additional 112 patients to

achieve potential benefit in one patient. The number

needed-to-treat of lowering 150-treatment line to

100-treatment line to potentially prevent one case of

paracetamol-induced liver injury is 112.

Despite these data, the clinical decision to

initiate NAC treatment may not depend solely

on the timed serum paracetamol concentration.

As illustrated in case 1, NAC treatments were

occasionally initiated based on the patient’s

presentation and doctor’s clinical judgement.

In our study, 23 of 112 patients with serum

paracetamol concentration plotted between 100- and 150-treatment lines were prescribed NAC for

similar reasons. Thus if the 100-treatment line is

used instead of the 150-treatment line, the actual

number of additional NAC treatment that would

have been needed is 89 (ie 112-23 cases).

Limitations

In the clinical management of paracetamol overdose

in Hong Kong, patients may be discharged if their

serum paracetamol level is below the treatment line

and there are no active clinical symptoms. Although

no patient in this study was readmitted for hepatitis,

there may have been others who developed chemical

hepatitis and who were not brought to our attention.

Thus the incidence of liver injury will have been

underestimated.

Conclusions

Neither the 150- nor 100-treatment line can fully

cover all patients who develop significant liver

injury following paracetamol overdose. The failure

rate of the treatment lines and potential financial

burden were studied. This serves as the basis for

future considerations of treatment in Hong Kong for

paracetamol overdose.

References

1. Chan YC, Tse ML, Lau FL. Hong Kong Poison Information

Centre: Annual Report 2012. Hong Kong J Emerg Med

2013;20:371-81.

2. Davidson DG, Eastham WN. Acute liver necrosis following

overdose of paracetamol. Br Med J 1966;2:497-9. Crossref

3. Prescott LF, Illingworth RN, Critchley JA, Stewart MJ,

Adam RD, Proudfoot AT. Intravenous N-acetylcysteine:

the treatment of choice for paracetamol poisoning. BMJ

1979;2:1097-100. Crossref

4. Smilkstein MJ, Knapp GL, Kulig KW, Rumack BH. Efficacy

of oral N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of acetaminophen

overdose. Analysis of the national multicenter study (1976

to 1985). N Engl J Med 1988;319:1557-62. Crossref

5. Rumack BH. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: the first 35

years. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2002;40:3-20. Crossref

6. Rowden AK, Norvell J, Eldridge DL, Kirk MA. Updates on

acetaminophen toxicity. Med Clin North Am 2005;89:1145-59. Crossref

7. Daly FF, Fountain JS, Murray L, Graudins A, Buckley NA;

Panel of Australian and New Zealand clinical toxicologists.

Guidelines for the management of paracetamol

poisoning in Australia and New Zealand—explanation

and elaboration. A consensus statement from clinical

toxicologists consulting to the Australasian poisons

information centres. Med J Aust 2008;188:296-301.

8. Paracetamol overdose: new guidance on use of intravenous

acetylcysteine. Commission on Human Medicines, United Kingdom. Available from: https://www.cas.dh.gov.uk/ViewandAcknowledgment/ViewAttachment.aspx?Attachment_id=101488. Accessed 7 Jul 2015.

9. Beer C, Pakravan N, Hudson M, et al. Liver unit admission

following paracetamol overdose with concentrations below

current UK treatment thresholds. QJM 2007;100:93-6. Crossref

10. Rumack BH, Matthew H. Acetaminophen poisoning and

toxicity. Pediatrics 1975;55:871-6.

11. Head 140, Expenditure estimates, The 2014-15 Budget,

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, People’s

Republic of China. Available from: http://www.budget.gov.hk/2014/eng/pdf/head140.pdf. Accessed 19 Nov 2014.

12. McQuade DJ, Dargan PI, Keep J, Wood DM. Paracetamol

toxicity: What would be the implications of a change in UK

treatment guidelines? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2012;68:1541-7. Crossref