EDITORIAL

Kidney Health for All: bridging the gap in kidney health education and literacy

Robyn G Langham, MB, BS, PhD1 #; Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh, MD, PhD2 #; Ann Bonner, RN, PhD3; Alessandro Balducci, MD4 #; LL Hsiao, MD, PhD5 #; Latha A Kumaraswami, BA6 #; Paul Laffin, MS7 #; Vassilios Liakopoulos, MD, PhD8 #; Gamal Saadi, MD9 #; Ekamol Tantisattamo, MD, MPH2;

Ifeoma Ulasi, MB, BS, MSc10 #; SF Lui, MD11 #; for the World Kidney Day Joint Steering Committee#

1 St Vincent’s Hospital, Department of Medicine, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

2 Division of Nephrology, Hypertension and Kidney Transplantation, Department of Medicine, University of California Irvine School of Medicine, Orange, California, United States

3 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Griffith University, Southport, Queensland, Australia

4 Italian Kidney Foundation, Rome, Italy

5 Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Renal Division, Department of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, United States

6 Tamilnad Kidney Research (TANKER) Foundation, The International Federation of Kidney Foundations–World Kidney Alliance

(IFKF–WKA), Chennai, India

7 International Society of Nephrology, Brussels, Belgium

8 Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, First Department of Internal Medicine, AHEPA Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

9 Nephrology Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt

10 Renal Unit, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Nigeria, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu, Nigeria

11 International Federation of Kidney Foundations–World Kidney Alliance, The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

# Members of the World Kidney Day Steering Committee

Full paper in PDF

Full paper in PDF

Abstract

The high burden of kidney disease, global disparities in kidney care, and poor outcomes of kidney failure bring a concomitant growing burden to persons affected, their families, and carers, and the community at large. Health literacy is the degree to which persons and organisations have or equitably enable individuals to have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to make informed health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others. Rather than viewing health literacy as a patient deficit, improving health literacy largely rests with healthcare providers communicating and educating effectively in codesigned partnership with those with kidney disease. For kidney policy makers, health literacy provides the imperative to shift organisations to a culture that places the person at the centre of healthcare. The growing capability of and access to technology provides new opportunities to enhance education and awareness of kidney disease for all stakeholders. Advances in telecommunication, including social media platforms, can be leveraged to enhance persons’ and providers’ education; The World Kidney Day declares 2022 as the year of “Kidney Health for All” to promote global teamwork in advancing strategies in bridging the gap in kidney health education and literacy. Kidney organisations should work towards shifting the patient-deficit health literacy narrative to that of being the responsibility of healthcare providers and health policy makers. By engaging in and supporting kidney health–centred policy making, community health planning, and health literacy approaches for all, the kidney communities strive to prevent kidney diseases and enable living well with kidney disease.

Given the high burden of kidney disease and global disparities related to kidney care, in carrying forward our mission of advocating Kidney Health for All, the challenging issue of bridging the well-identified gap in the global understanding of kidney disease and its health literacy is the theme for World Kidney Day (WKD) 2022. Health literacy is defined as the degree to which persons and organisations have—or equitably enable individuals to have—the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.

1 Not only is there is growing recognition of the role that health literacy has in determining outcomes for persons affected by kidney disease and the community in general, but there is an emergent imperative for policy makers worldwide to be informed and cognizant of opportunities and real measurable outcomes that can be achieved through kidney-specific preventative strategies.

The global community of people

with kidney disease

Most people are not aware of what kidneys are for

or even where their kidneys are. For those afflicted

by disease and the subsequent effects on overall

health, effective healthcare provider communication

is required to support individuals to be able to

understand what to do, to make decisions, and to

take action. Health literacy involves more than

functional abilities of an individual; it is also the

cognitive and social skills needed to gain access

to, understand, and use information to manage

health conditions.

2 It is also contextual

3 in that

as health needs change, so too does the level of

understanding and ability to problem solve alter. Health literacy is, therefore, an interaction between

individuals, healthcare providers, and health policy

makers.

4 This is why the imperatives around health

literacy are now recognised as indicators for the

quality of local and national healthcare systems and

healthcare professionals within them.

5 For chronic

kidney disease (CKD), as the disease progresses

alongside other health changes and increasing

treatment complexities, it becomes more difficult for

individuals to manage.

6 Promoted in health policy

for around a decade involving care partnerships

between health-centred policy, community health

planning, and health literacy,

7 current approaches

need to be shifted forward (

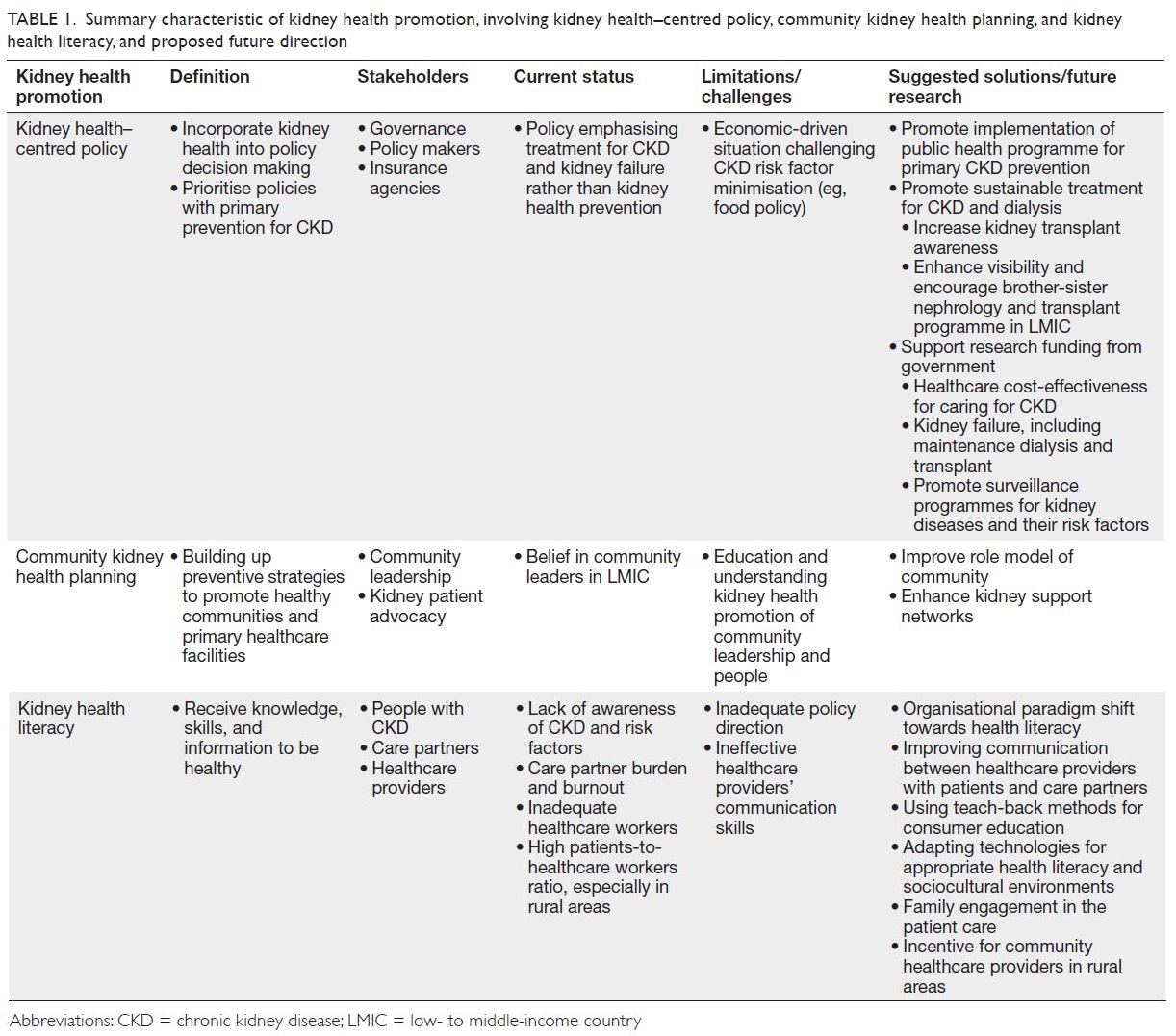

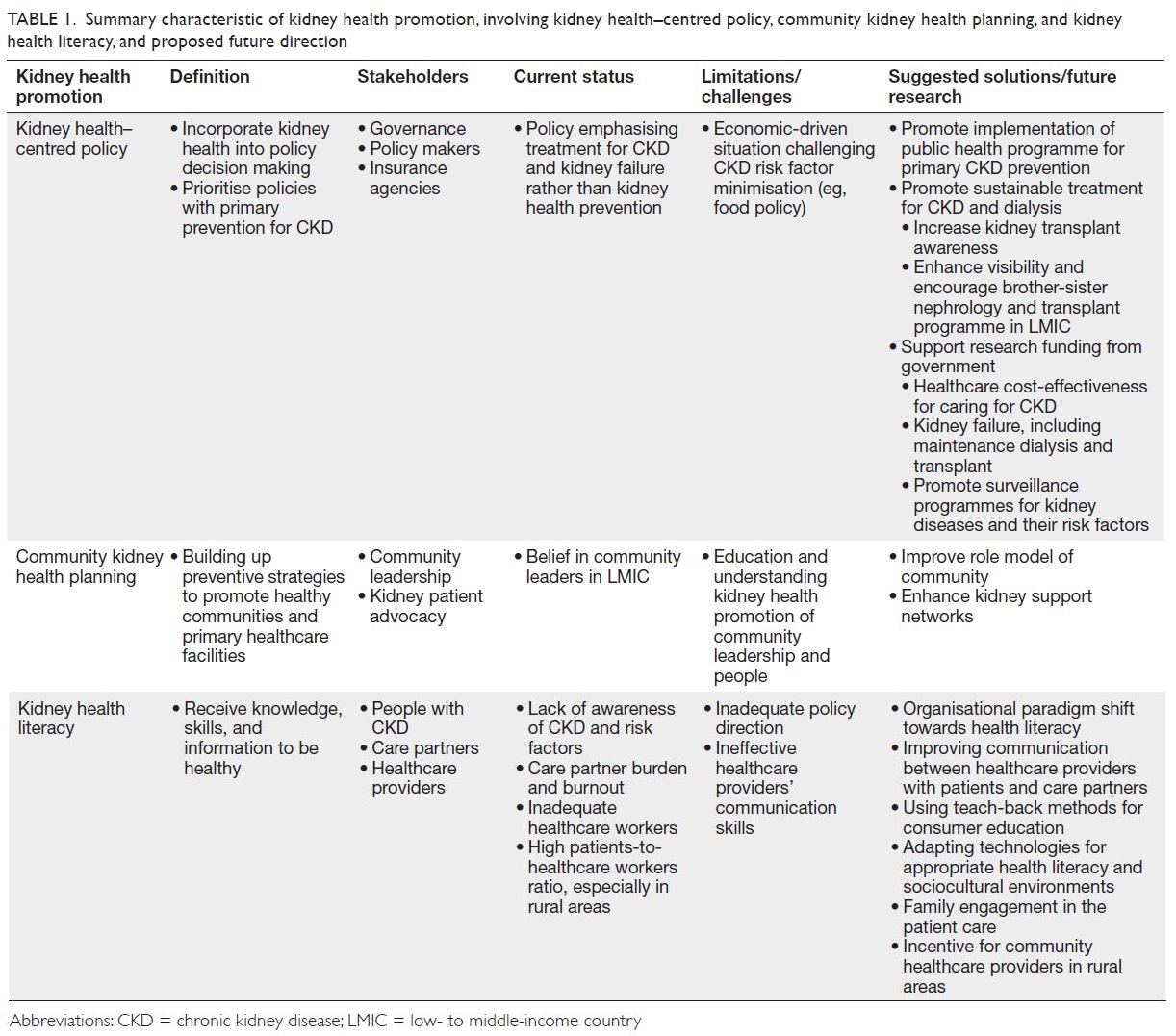

Table 1).

Table 1.

Table 1. Summary characteristic of kidney health promotion, involving kidney health–centred policy, community kidney health planning, and kidney

health literacy, and proposed future direction

Assessing health literacy necessitates the use

of appropriate multidimensional patient-reported measures, such as the World Health Organization–recommended Health Literacy Questionnaire

(available in over 30 languages) rather than tools

measuring only functional health literacy (eg, Rapid

Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine or Short

Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults).

8 It is

therefore not surprising that studies of low health

literacy (LHL) abilities in people with CKD have

been demonstrated to be associated with poor

CKD knowledge, self-management behaviours,

and health-related quality of life and in those with

greater co-morbidity severity.

7 Unfortunately, most

CKD studies have measured only functional health

literacy, so the evidence that LHL results in poorer

outcomes, particularly that it increases healthcare

utilisation and mortality

9 and reduces access to

transplantation,

10 is weak.

Recently, health literacy is now considered to be

an important bridge between lower socioeconomic

status and other social determinants of health.

4

Indeed, this is not a feature that can be measured

by the gross domestic product of a country, as

the effects of LHL on the extent of CKD in the

community are experienced globally regardless of

country income status. The lack of awareness of

risk factors of kidney disease, even in those with

high health literacy abilities, is a testament to the

difficulties in understanding this disease, and why

the United States, for instance, recommends that

a universal precautions approach towards health

literacy is undertaken.

11

So, what does the perfect health literacy

programme look like for people with CKD? In

several high-income countries, there are national

health literacy action plans with the emphasis

shifted to policy directives, organisational culture,

and healthcare providers. In Australia, for instance,

a compulsory health literacy accreditation standard

makes the healthcare organisation responsible

for ensuring providers are cognizant of individual

health literacy abilities.

12 Although many high-income

countries, healthcare organisations, non-governmental

organisations, and jurisdictions are

providing an array of consumer-facing web-based

programmes that provide detailed information and

self-care training opportunities, most are largely

designed for individual/family use that are unlikely

to mitigate LHL. There is, however, substantial

evidence that interventions improving healthcare

provider communication are more likely to improve

understanding of health problems and abilities to

adhere to complex treatment regimens.

13

Access to information that is authentic and

tailored specifically to the needs of the individual and

the community is the aim. The challenge is recognised

acutely in more remote and low- to middle-income

countries of the world, specifically the importance

of culturally appropriate knowledge provision. The principles of improving health literacy are the same,

but understanding how to proceed, and putting

consumers in charge, with a co-design approach,

is critical and may result in a different outcome

in more remote parts of the world. This principle

especially applies to communities that are smaller,

with less access to electronic communication and

healthcare services, where the level of health literacy

is shared across the community and where what

affects the individual also affects all the community.

Decision support systems are different, led by elders,

and in turn educational resources are best aimed at

improving knowledge of the whole community.

A systematic review of the evaluation of

interventions and strategies shows this area of

research is still at an early stage,

14 with no studies

unravelling the link between LHL and poor CKD

outcomes. The best evidence is in supporting

targeted programmes on improving communication

capabilities of healthcare professionals as central.

One prime example is ‘teach-back’, a cyclical, simple,

low-cost education intervention, which shows

promise for improving communication, knowledge,

and self-management in the CKD populations in

low- or high-income countries.

15 Furthermore,

the consumer-led voice has articulated research

priorities that align closely with principles felt to be

important to the success of education: building new

education resources, devised in partnership with

consumers, and focussed on the needs of vulnerable

groups. Indeed, programmes that address the lack

of culturally safe, person-centred and holistic care,

along with improving the communication skills

of health professionals, are crucial for those with

CKD.

16

The networked community of

kidney healthcare workers

Nonphysician healthcare workers, including nurses

and advanced practice providers (physician assistants

and nurse practitioners) as well as dietitians,

pharmacists, social workers, technicians, physical

therapists, and other allied health professionals,

often spend more time with persons with kidney

disease, compared with nephrologists and other

physician specialists. In an ambulatory care setting at

an appointment, in the emergency department, or in

the in-patient setting, these healthcare professionals

often see and relate to the patient first, last, and

in between, given that physician encounters are

often short and focused. Hence, the nonphysician

healthcare workers have many opportunities to

discuss kidney disease-related topics with the

individuals and their care partners and to empower

them.

17 18 For instance, medical assistants can help

identify those with or at risk of developing CKD and

can initiate educating them and their family members about the role of diet and lifestyle modification for

primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of CKD

while waiting to see the physician.

19 Some healthcare

workers provide networking and support for kidney

patient advocacy groups and kidney support

networks, which have been initiated or expanded via

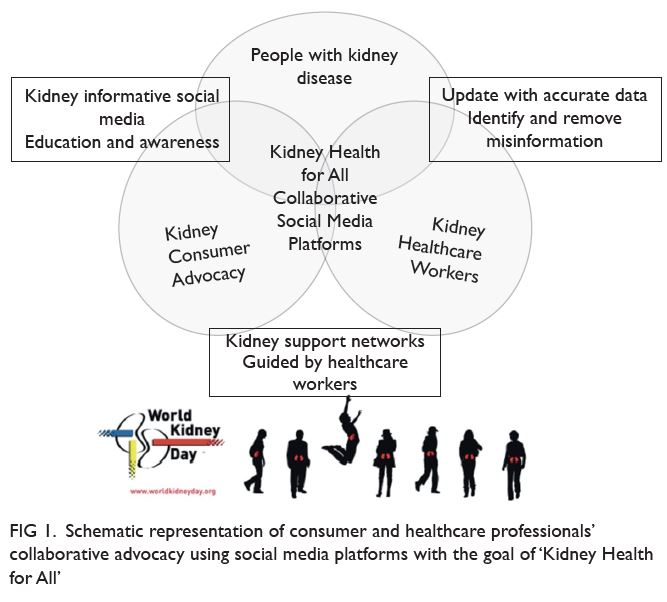

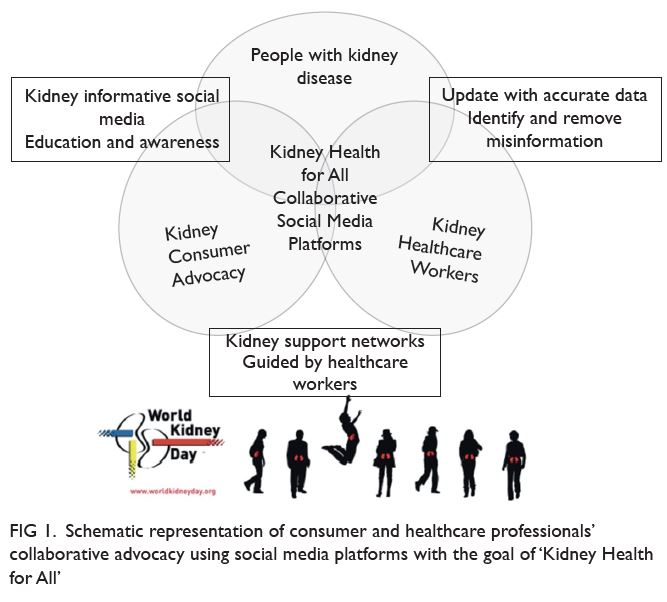

social media platforms (

Fig 1).

20 21 Studies examining the efficacy of social media in kidney care and

advocacy are on the way.

22 23

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of consumer and healthcare professionals’

collaborative advocacy using social media platforms with the goal of ‘Kidney Health for All’

Like physicians, many activities of nonphysician

healthcare workers have been increasingly

affected by the rise of electronic health recording

and growing access to internet-based resources,

including social media, that offer educational

materials related to kidney health, including kidney-preserving

therapies with traditional and emerging

interventions.

24 These resources can be used for both

self-education and for networking and advocacy on

kidney disease awareness and learning. Increasingly,

more healthcare professionals are engaged in some

types of social media-based activities, as shown

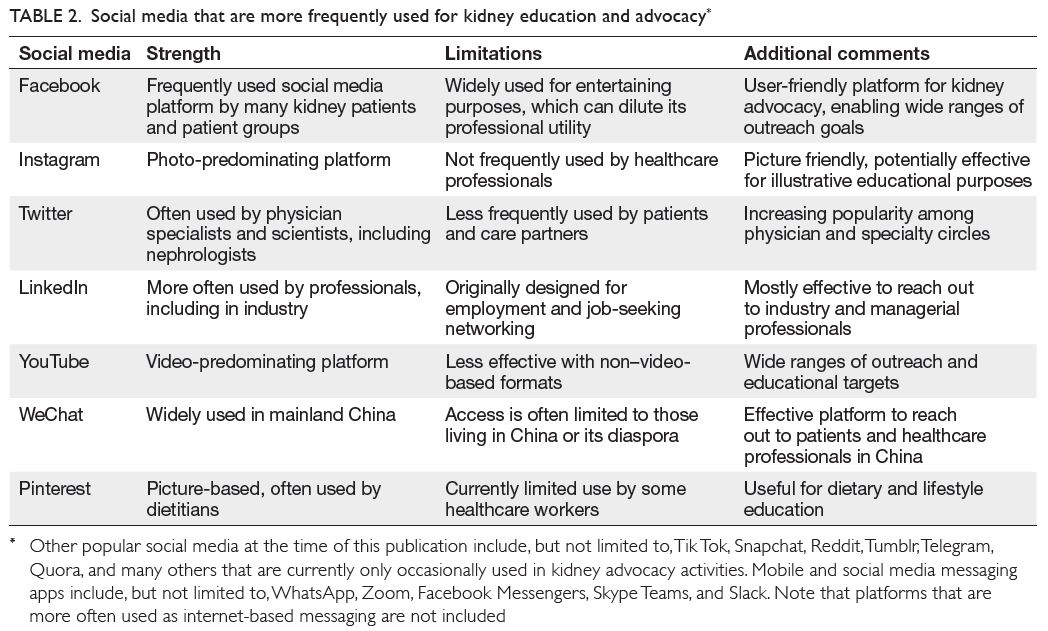

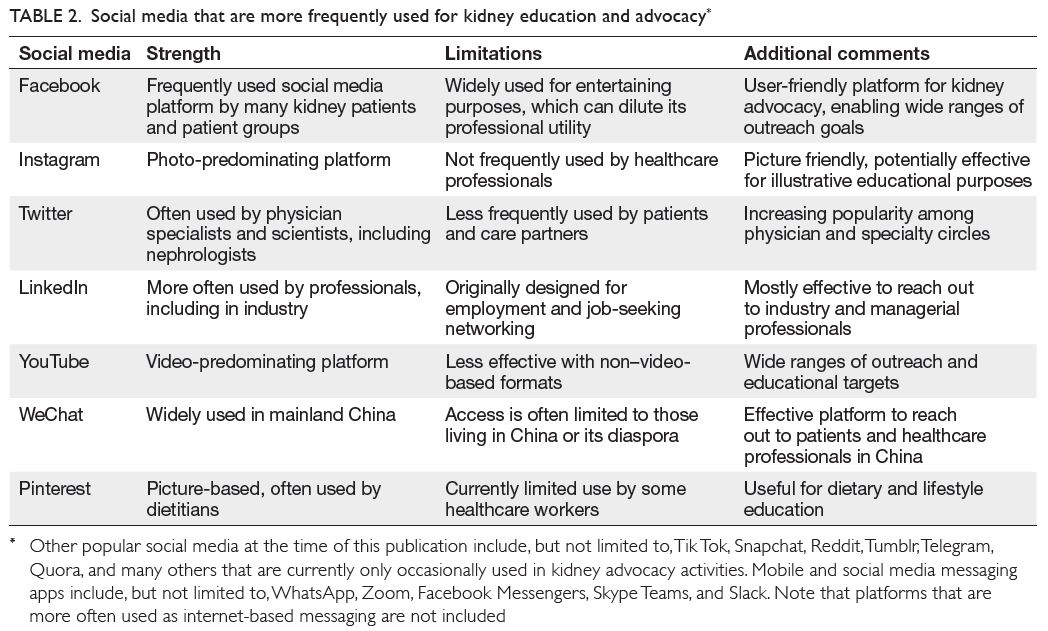

in

Table 2. At the time of this writing, the leading

social media used by many—but not all—kidney

healthcare workers include Facebook, Instagram,

Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube. In some regions of

the world, certain social media are more frequently

used than others given unique cultural or access

constellations (eg, WeChat is a platform often used

by healthcare workers and patient groups in China).

Some healthcare professionals, such as managers

and those in leadership and advocacy organisation

positions, may choose to embark on social media to

engage those with CKD and their care partners or

other healthcare professionals in alliance building

and marketing. To that end, effective communication

strategies and outreach skills specific to responsible

use of social media can provide clear advantages

given that these skills and strategies are different

and may need modification in those with LHL. It

is imperative to ensure the needed knowledge and training for an accountable approach to social media

is provided to healthcare providers, so that these

outreach strategies are utilised with the needed

awareness of their unique strengths and pitfalls, as

follows.

25

Table 2.

Table 2. Social media that are more frequently used for kidney education and advocacy

(i) Consumers’ and care partners’ confidentiality

may not be breached upon posting anything on

social media, including indirect referencing to

a specific individual or a particular description

of a condition unique to a specific person (eg,

upon soliciting for transplant kidney donors on

social media).

26 27

ii) Confidential information about clinics,

hospitals, dialysis centres, or similar healthcare

and advocacy entities may not be disclosed on

social media without ensuring that the needed

processes, including collecting authorisations

to disclose, are undertaken.

(iii) Healthcare workers’ job security and careers

should remain protected with thorough review

of the content of the messages and illustrations/videos before online posting.

(iv) Careless and disrespectful language and

emotional tones are often counterproductive

and may not be justified under the context of

freedom of speech.

The global kidney community of

policy and advocacy

Policy and advocacy are well-recognised tools

that, if properly deployed, can bring about change

and paradigm shift at the jurisdictional level. The

essence of advocating for policy change to better

address kidney disease is, in itself, an exercise in

improving health literacy of the policy makers.

Policy development, at its core, is a key stakeholder

or stakeholder group (eg, the kidney community,

which believes that a problem exists that should

be tackled through governmental action). There

is increasing recognition of the importance of

formulating succinct, meaningful, and authentic

information, akin to improving health literacy, to

present to governments for action.

Robust and efficacious policy is always

underpinned by succinct and applicable information;

however, the development and communication of

this message, designed to bridge the gap in knowledge

of relevant jurisdictions, is only part of the process of

policy development. An awareness of the process is

important to clinicians who are aiming to advocate

for effective change in prevention or improvement of

outcomes in the CKD community.

Public policies, the plans for future action

accepted by governments, are articulated through

a political process in response to stakeholder

observation, usually written as a directive, law,

regulation, procedure, or circular. Policies are purpose fit and targeted to defined goals and specific

societal problems and are usually a chain of actions

effected to solve those societal problems.

28 Policies

are an important output of political systems. Policy

development can be formal, passing through

rigorous lengthy processes before adoption (such

as regulations), or it can be less formal and quickly

adopted (such as circulars). As already mentioned,

the governmental action envisaged by the key

stakeholders as a solution to a problem is at its core.

The process enables stakeholders to air their views

and bring their concerns to the fore. Authentic

information that is meaningful to the government

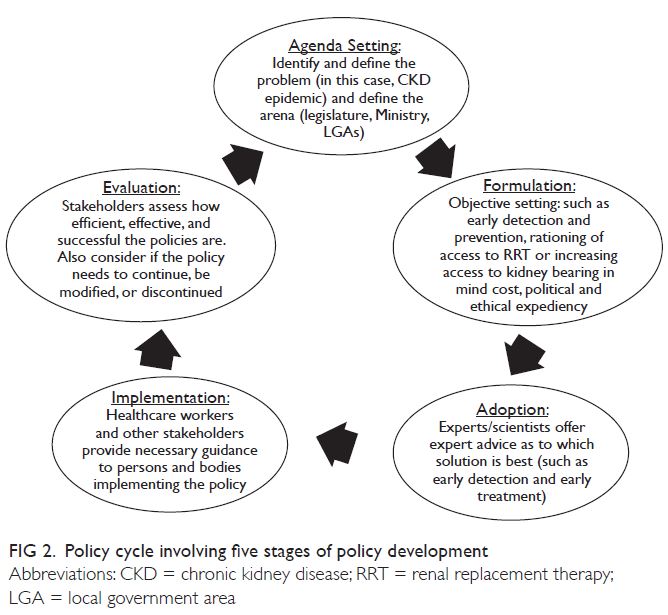

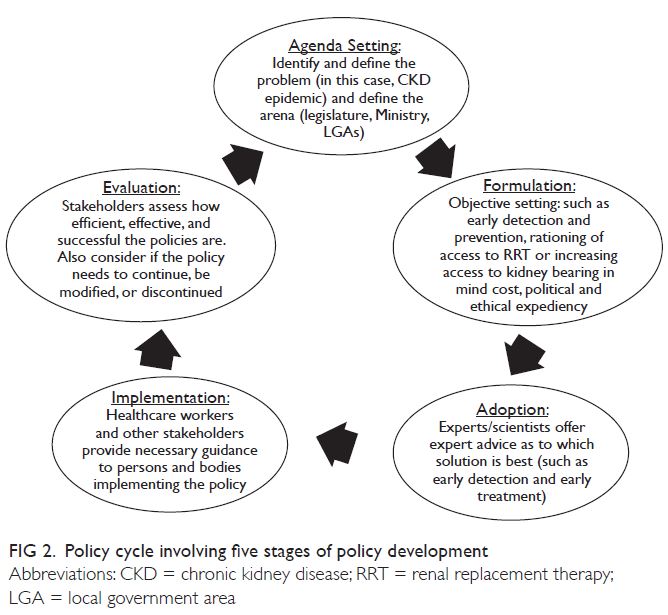

is critical. The policy development process can be

stratified into five stages (ie, the policy cycle), as

depicted by Anderson (1994)

29 and adapted and

modified by other authors

30 (

Fig 2). The policy cycle

constitutes an expedient framework for evaluating

the key components of the process.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Policy cycle involving five stages of policy development

Subsequently, the policy moves on to the

implementation phase. This phase may require

subsidiary policy development and adoption of

new regulations or budgets (implementation).

Policy evaluation is integral to the policy processes

and applies evaluation principles and methods to

assess the content, implementation, or impact of

a policy. Evaluation facilitates understanding and

appreciation of the worth and merit of a policy as well

as the need for its improvement. More important, of

the five principles of advocacy that underline policy

making,

31 the most important for clinicians engaged

in this space is that of commitment, persistence, and patience. Advocacy takes time to yield the desired

results.

The Advocacy Planning Framework,

developed by Young and Quinn in 2002, 30 consists

of overlapping circles representing three sets of

concepts (way into the process, the messenger, and

message and activities) that are key to planning any

advocacy campaign:

(i) “Way into the process”: discusses the best

approaches to translate ideas into the target

policy debate and identify the appropriate

audience to target.

(ii) Messenger: talks about the image maker

or face of the campaign and other support

paraphernalia that are needed.

(iii) Message and activities: describe what can

be said to the key target audiences that is

engaging and convincing. And how best it

can be communicated through appropriate

communication tools.

Advocacy is defined as “an effort or campaign

with a structured and sequenced plan of action

which starts, directs, or prevents a specific policy

change.”

31 The goal being to influence decision

makers through communicating directly with them

or getting their commitment through secondary

audiences (advisers, the media, or the public) to

the end that the decision maker understands, is

convinced, takes ownership of the ideas, and finally

has the compulsion to act.

31 As with improving

health literacy, it is the communication of ideas to

policy makers for adoption and implementation as

policy that is key. There is much to be done with

bridging this gap in understanding of the magnitude

of community burden that results from CKD.

Without good communication, many good ideas and

solutions do not reach communities and countries

where they are needed. Again, aligned with the

principles of developing resources for health literacy,

the approach also needs to be nuanced according to

the local need, aiming to have the many good ideas

and solutions be communicated to communities and

countries where they are needed

Advocacy requires galvanising momentum and

support for the proposed policy or recommendation.

The process is understandably slow as it involves

discussions and negotiations for paradigms, attitudes,

and positions to shift. In contemplating advocacy

activities, multiple factors must be considered,

interestingly not too dissimilar to that of building

health literacy resources: What obstructions are

disrupting the policy making process from making

progress? What resources are available to enable the

process to succeed? Is the policy objective achievable

considering all variables? Is the identified problem

already being considered by the policy makers

(government or multinational organisations)?

Any interest or momentum generated around it? Understandably, if there is some level of interest and

if governments already have a spotlight on the issue,

it is likely to succeed.

Approaches to choose from include the

following

31 32:

Advising (researchers are commissioned to

produce new evidence-based proposals to assist

the organisation in decision making).

Activism: involves petitions, public

demonstrations, posters, fliers, and leaflet

dissemination, often used by organisations to

promote a certain value set.

Media campaign: having public pressure on

decision makers helps in achieving results

Lobbying: entails face-to-face meetings with

decision makers; often used by business

organisations to achieve their purpose.

Here lies the importance of effective and

successful advocacy to stakeholders, including policy

makers, healthcare professionals, communities,

and key change makers in society. The WKD, since

inception, has aimed at playing this role. World

Kidney Day has gained people’s trust by delivering

relevant and accurate messaging and supporting

leaders in local engagement, and it is celebrated by

kidney care professionals, celebrities, those with

the disease, and their caregivers all over the world.

To achieve the goal, an implementation framework

of success in a sustainable way includes creativity,

collaboration, and communication.

The ongoing challenge for the International

Society of Nephrology and International Federation

of Kidney Foundations—World Kidney Alliance,

through the Joint Steering Committee of WKD,

is to operationalise how to collate key insights

from research and analysis to effectively feed the

policy making process at the local, national, and

international levels, to inform or guide decision

making (ie, increasing engagement of governments

and organisations, like World Health Organization,

United Nations, and regional organisations,

especially in low-resource settings). There is a clear

need for ongoing renewal of strategies to increase

efforts at closing the gap in kidney health literacy,

empowering those affected with kidney disease

and their families, giving them a voice to be heard,

and engaging with civil society. This year, the Joint

Steering Committee of WKD declares “Kidney

Health for All” as the theme of the 2022 WKD to

emphasise and extend collaborative efforts among

people with kidney disease, their care partners,

healthcare providers, and all involved stakeholders

for elevating education and awareness on kidney

health and saving lives with this disease.

Conclusions

In bridging the gap of knowledge to improve

outcomes for those with kidney disease on a global basis, an in-depth understanding of the needs of the

community is required. The same can be said for

policy development, understanding the processes in

place for engagement of governments worldwide, all

underpinned by the important principle of codesign

of resources and policy that meets the needs of the

community for which it is intended.

For WKD 2022, kidney organisations, including

the International Society of Nephrology and

International Federation of Kidney Foundations—World Kidney Alliance, have a responsibility to

immediately work towards shifting the patient-deficit

health literacy narrative to that of being the

responsibility of clinicians and health policy makers.

Low health literacy occurs in all countries regardless

of income status; hence, simple, low-cost strategies

are likely to be effective. Communication, universal

precautions, and teach-back can be implemented by

all members of the kidney healthcare team. Through

this vision, kidney organisations will lead the shift

to improved patient-centred care, support for care

partners, health outcomes, and the global societal

burden of kidney healthcare.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception, preparation, and editing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

K Kalantar-Zadeh reports honoraria from Abbott, Abbvie,

ACI Clinical, Akebia, Alexion, Amgen, Ardelyx, AstraZeneca,

Aveo, BBraun, Cara Therapeutics, Chugai, Cytokinetics,

Daiichi, DaVita, Fresenius, Genentech, Haymarket Media,

Hospira, Kabi, Keryx, Kissei, Novartis, Pfizer, Regulus,

Relypsa, Resverlogix, Dr Schaer, Sandoz, Sanofi, Shire,

Vifor, UpToDate, and ZS-Pharma. V Liakopoulos reports

nonfinancial support from Genesis Pharma. G Saadi

reports personal fees from Multicare, Novartis, Sandoz, and

AstraZeneca. E Tantisattamo reports nonfinancial support

from Natera. Other authors declared no competing interests.

Funding/support

This editorial received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration

This article was published in

Kidney International (Langham

RG, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Bonner A, et al. Kidney health for

all: bridging the gap in kidney health education and literacy.

Kidney International. 2022;101(3):432-440.

https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.kint.2021.12.017), and reprinted concurrently

in several journals. The articles cover identical concepts and

wording, but vary in minor stylistic and spelling changes,

detail, and length of manuscript in keeping with each journal’s

style. Any of these versions may be used in citing this article.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy

people 2030: What is health literacy? Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/index.html.

Accessed 16 Jan 2022.

2. Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc

Sci Med 2008;67:2072-8.

Crossref3. Lloyd A, Bonner A, Dawson-Rose C. The health

information practices of people living with chronic health

conditions: implications for health literacy. J Librariansh

Inf Sci 2014;46:207-16.

Crossref4. Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, et al. Health

literacy and public health: a systematic review and

integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health

2012;12:80.

Crossref5. Nutbeam D, Lloyd JE. Understanding and responding to

health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev

Public Health 2021;42:159-73.

Crossref6. Shah JM, Ramsbotham J, Seib C, Muir R, Bonner A. A

scoping review of the role of health literacy in chronic

kidney disease self-management. J Ren Care 2021;47:221-33.

Crossref7. Dinh HT, Nguyen NT, Bonner A. Healthcare systems

and professionals are key to improving health literacy in

chronic kidney disease. J Ren Care 2022;48:4-13.

Crossref8. Dodson S, Good S, Osborne R. Health Literacy Toolkit for

Low- and Middle-income Countries: a Series of Information

Sheets to Empower Communities and Strengthen Health

Systems. New Delhi: World Health Organization; 2015.

9. Taylor DM, Fraser S, Dudley C, et al. Health literacy and

patient outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a systematic

review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018;33:1545-58.

Crossref10. Taylor DM, Bradley JA, Bradley C, et al. Limited health

literacy is associated with reduced access to kidney

transplantation. Kidney Int 2019;95:1244-52.

Crossref11. Brega AG, Barnard J, Mabachi NM, et al. AHRQ Health

Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit, Second Edition.

(Prepared by Colorado Health Outcomes Program,

University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus under

Contract No. HHSA290200710008, TO#10.) AHRQ

Publication No. 15-0023-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality; Jan 2015.

12. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health

Care. Health literacy: taking action to improve safety and

quality. Sydney: ACSQHC, 2014. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/health-literacy-taking-action-improve-safety-and-quality. Accessed 17 Jan 2022.

13. Visscher BB, Steunenberg B, Heijmans M, et al. Evidence

on the effectiveness of health literacy interventions in the

EU: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1414.

Crossref14. Boonstra MD, Reijneveld SA, Foitzik EM, Westerhuis R,

Navis G, de Winter AF. How to tackle health literacy

problems in chronic kidney disease patients? A systematic

review to identify promising intervention targets and

strategies. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020;36:1207-21.

Crossref15. Nguyen NT, Douglas C, Bonner A. Effectiveness of selfmanagement

programme in people with chronic kidney

disease: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Adv

Nurs 2019;75:652-64.

Crossref16. Synnot A, Bragge P, Lowe D, et al. Research priorities in

health communication and participation: international

survey of consumers and other stakeholders. BMJ Open

2018;8:e019481.

Crossref17. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Li PK, Tantisattamo E, et al. Living

well with kidney disease by patient and care-partner empowerment: kidney health for everyone everywhere.

Kidney Int 2021;99:278-84.

Crossref18. Jager KJ, Kovesdy C, Langham R, Rosenberg M,

Jha V, Zoccali C. A single number for advocacy and

communication-worldwide more than 850 million

individuals have kidney diseases. Kidney Int 2019;96:1048-50.

Crossref19. Li PK, Garcia-Garcia G, Lui SF, et al. Kidney health for

everyone everywhere—from prevention to detection and

equitable access to care. Kidney Int 2020;97:226-32.

Crossref20. Gilford S. Patients helping patients: the Renal Support

Network. Nephrol Nurs J 2007;34:76.

21. Muhammad S, Allan M, Ali F, Bonacina M, Adams M.

The renal patient support group: supporting patients with

chronic kidney disease through social media. J Ren Care

2014;40:216-8.

Crossref22. Li WY, Chiu FC, Zeng JK, et al. Mobile health app with

social media to support self-management for patients with

chronic kidney disease: prospective randomized controlled

study. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e19452.

Crossref23. Pase C, Mathias AD, Garcia CD, Garcia Rodrigues C.

Using social media for the promotion of education and

consultation in adolescents who have undergone kidney

transplant: protocol for a randomized control trial. JMIR

Res Protoc 2018;7:e3.

Crossref24. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Jafar T, Nitsch D, Neuen BL, Perkovic V.

Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2021;398:786-802.

Crossref25. Chen L, Sivaparthipan CB, Rajendiran S. Unprofessional

problems and potential healthcare risks in individuals’

social media use. Work 2021;68:945-53.

Crossref26. Henderson ML, Herbst L, Love AD. Social media and

kidney transplant donation in the United States: clinical

and ethical considerations when seeking a living donor.

Am J Kidney Dis 2020;76:583-5.

Crossref27. Henderson ML. Social media in the identification of living

kidney donors: platforms, tools, and strategies. Curr

Transplant Rep 2018;5:19-26.

Crossref28. Newton K, van Deth JW, editors. Foundations of

Comparative Politics Democracies of the Modern World.

2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

Crossref29. Anderson JE. Public Policymaking: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1994.

30. Young E, Quinn L, eds. Writing effective public policy

papers: a guide to policy advisers in Central and Eastern

Europe. Budapest, Hungary: Open Society Institute. 2002.

Available from: https://www.icpolicyadvocacy.org/sites/icpa/files/downloads/writing_effective_public_policy_papers_young_quinn.pdf. Accessed 13 Dec 2021.

31. Young E, Quinn L, eds. Making research evidence matter: a

guide to policy advocacy in transition countries. Budapest,

Hungary: Open Society Foundations. 2012. Available from:

https://advocacyguide.icpolicyadvocacy.org/sites/icpa-book.local/files/Policy_Advocacy_Guidebook_2012.pdf.

Accessed 13 Dec 2021.

32. Start D, Hovland I. Tools for policy impact: a handbook

for researchers, research and policy in development

programme. London, UK: Overseas Development

Institute. 2004. Available from: https://www.ndi.org/sites/default/files/Tools-for-Policy-Impact-ENG.pdf. Accessed 13 Dec 2021.