EDITORIAL

Mind the gap in kidney care: translating what we know into what we do

Valerie A Luyckx, MD1,2,3 #; Katherine R Tuttle, MD4,5 #; Dina Abdellatif, MD6 †; Ricardo Correa-Rotter, MD7 †; Winston WS Fung, MBBChir (Cantab), FRCP (Lond)8; Agnès Haris, MD, PhD9 †; LL Hsiao, MD2 †; Makram Khalife, BA10 ‡; Latha A Kumaraswami, BA11 †; Fiona Loud, BA10 ‡; Vasundhara Raghavan, BA10 ‡; Stefanos Roumeliotis, MD12; Marianella Sierra, BA10 ‡; Ifeoma Ulasi, MD13 †; Bill Wang, BA10 ‡; SF Lui, MD14 †; Vassilios Liakopoulos, MD, PhD12 †; Alessandro Balducci, MD15 †; for the World Kidney Day Joint Steering Committee

1 Department of Public and Global Health, Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Prevention Institute, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

2 Renal Division, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, United States

3 Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

4 Providence Medical Research Center, Providence Inland Northwest Health, Spokane, United States

5 Nephrology Division, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, United States

6 Department of Nephrology, Cairo University Hospital, Cairo, Egypt

7 Department of Nephrology and Mineral Metabolism, National Medical Science and Nutrition Institute Salvador Zubiran, Mexico City, Mexico

8 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

9 Nephrology Department, Péterfy Hospital, Budapest, Hungary

10 International Society of Nephrology Patient Liaison Advisory Group

11 Tamilnad Kidney Research Foundation, Chennai, India

12 2nd Department of Nephrology, AHEPA University Hospital Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

13 Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Nigeria, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu, Nigeria

14 Division of Health System, Policy and Management, The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

15 Italian Kidney Foundation, Rome, Italy

# Equal contribution

† Members of the World Kidney Day Joint Steering Committee

‡ Patient representatives of the Patient Liaison Advisory Group of the International Society of Nephrology

Full paper in PDF

Full paper in PDF

Abstract

Historically, it takes an average of 17 years to move

new treatments from clinical evidence to daily

practice. Given the highly effective treatments now

available to prevent or delay kidney disease onset

and progression, this is far too long. The time is

now to narrow the gap between what we know and

what we do. Clear guidelines exist for the prevention

and management of common risk factors for kidney

disease, such as hypertension and diabetes, but only

a fraction of people worldwide with these conditions

are diagnosed, and even fewer receive appropriate

treatment. Similarly, the vast majority of people living

with kidney disease are unaware of their condition, because in the early stages it is often silent. Even among

diagnosed patients, many do not receive appropriate

treatment for kidney disease. Considering the serious

consequences of kidney disease progression, kidney

failure, or death, it is imperative to initiate treatments

early and appropriately. Opportunities to diagnose

and treat kidney disease early must be maximised,

starting at the primary care level. Many systematic

barriers exist, encompassing patient, clinician, health

system, and societal factors. To preserve and improve

kidney health for everyone everywhere, each of these

barriers must be acknowledged so that sustainable

solutions are developed and implemented without

further delay.

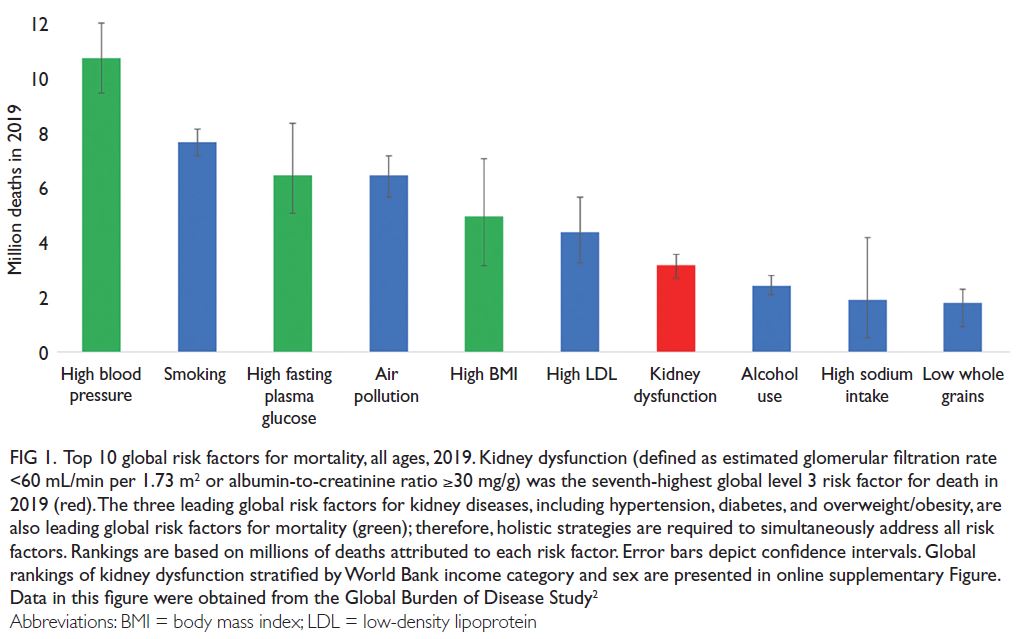

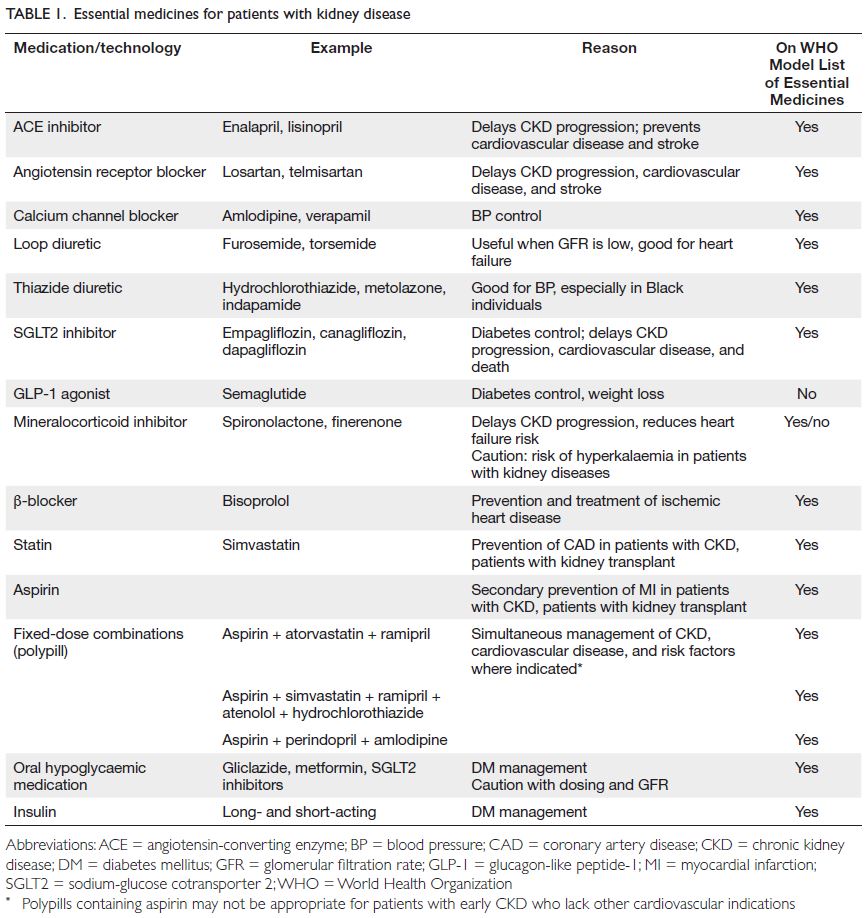

At least 1 in 10 people worldwide is living with a

kidney disease.

1 According to the Global Burden of

Disease study, >3.1 million deaths were attributed to

kidney dysfunction in 2019, making it the seventh

leading risk factor for mortality worldwide (

Fig 1 and

online supplementary Fig).

2 However, global mortality from all kidney diseases may actually

range from 5 to 11 million per year if the mortality

rate also includes estimated lives lost from acute

kidney injury and lack of access to renal replacement

therapy for kidney failure (KF), especially in lower-resource

settings.

3 These high global mortality rates reflect disparities in prevention, early detection,

diagnosis, and treatment of chronic kidney disease

(CKD).

4 Mortality rates from CKD are especially

high in some regions, particularly Central Latin

America and Oceania (islands of the South Pacific

Ocean), highlighting the need for urgent action.

5

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Top 10 global risk factors for mortality, all ages, 2019. Kidney dysfunction (defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m

2 or albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g) was the seventh-highest global level 3 risk factor for death in

2019 (red). The three leading global risk factors for kidney diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, and overweight/obesity, are

also leading global risk factors for mortality (green); therefore, holistic strategies are required to simultaneously address all risk

factors. Rankings are based on millions of deaths attributed to each risk factor. Error bars depict confidence intervals. Global

rankings of kidney dysfunction stratified by World Bank income category and sex are presented in online supplementary Figure.

Data in this figure were obtained from the Global Burden of Disease Study

2

Chronic kidney disease also represents

a substantial global economic burden, with

exponentially increasing costs as CKD progresses,

due to the costs of dialysis and transplantation, as

well as multiple co-morbidities and complications

that accumulate over time.

6 7 In the United

States, Medicare fee-for-service spending for all

beneficiaries with CKD was US$86.1 billion in 2021

(22.6% of total expenditures).

8 Data from many

lower-resource settings, where most healthcare

spending comprises out-of-pocket costs, are absent.

A recent study in Vietnam showed that the perpatient

cost of CKD was higher than the gross

domestic product per capita.

7 In Australia, it has

been estimated that early diagnosis and prevention

of CKD could save the health system AU$10.2 billion

over 20 years.

9

Although there is regional variation in the

causes of CKD, the risk factors with the highest

population-attributable factors for age-standardised

CKD-related disease-adjusted life years are

hypertension (51.4%), a high fasting plasma glucose

level (30.9%), and a high body mass index (26.5%).

10

These risk factors are also leading risk factors for

mortality worldwide (

Fig 1). Only 40% and 60% of people with hypertension and diabetes, respectively,

are aware of their diagnosis; considerably smaller

proportions of these individuals are receiving

treatment and reaching therapeutic targets.

11 12

Moreover, at least 1 in 5 people with hypertension

and 1 in 3 people with diabetes also have CKD.

13

Most cases of CKD can be prevented through

healthy lifestyles, prevention and management

of risk factors, avoidance of acute kidney injury,

optimisation of maternal and child health, mitigation

of climate change, and efforts to address social and

structural determinants of health.

3 Nevertheless,

the benefits of some of these measures may only

be evident in future generations. Until then, early

diagnosis and risk stratification create opportunities

to introduce therapies that can slow, halt, or even

reverse CKD.

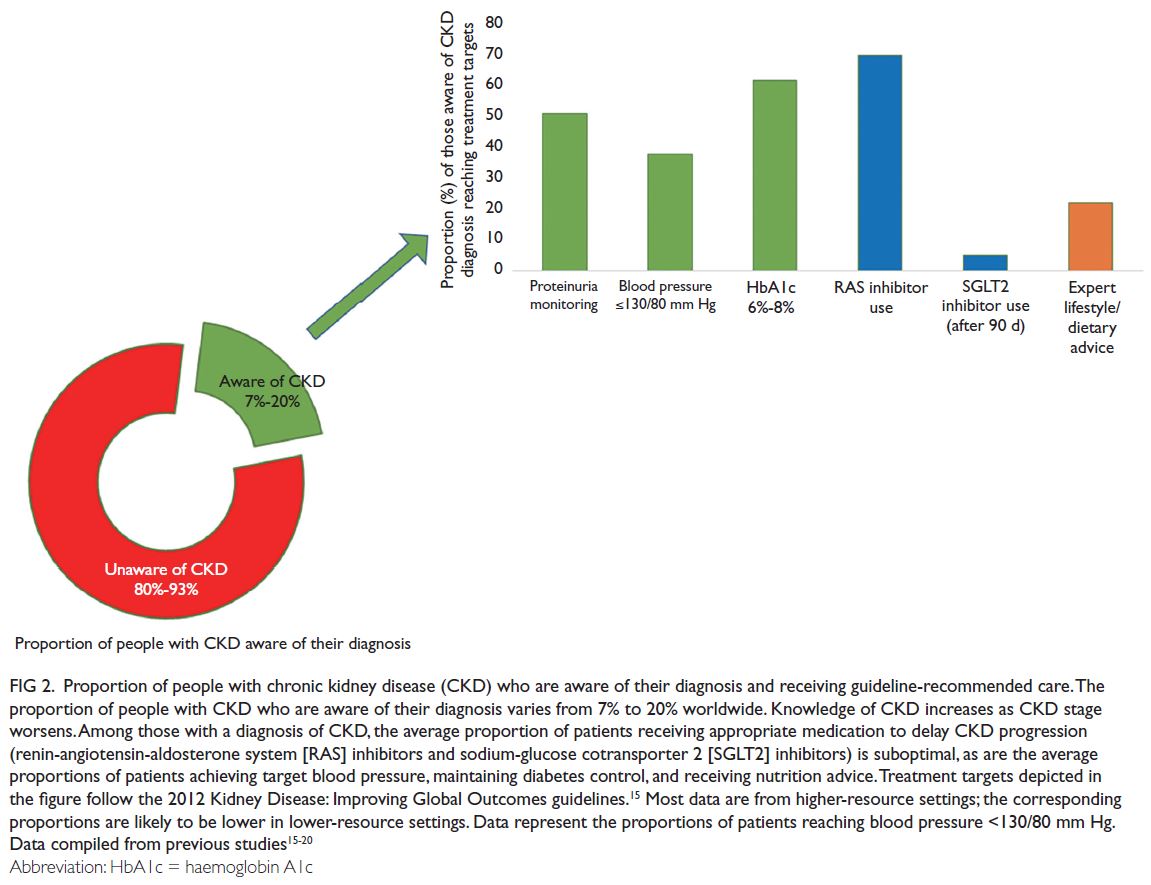

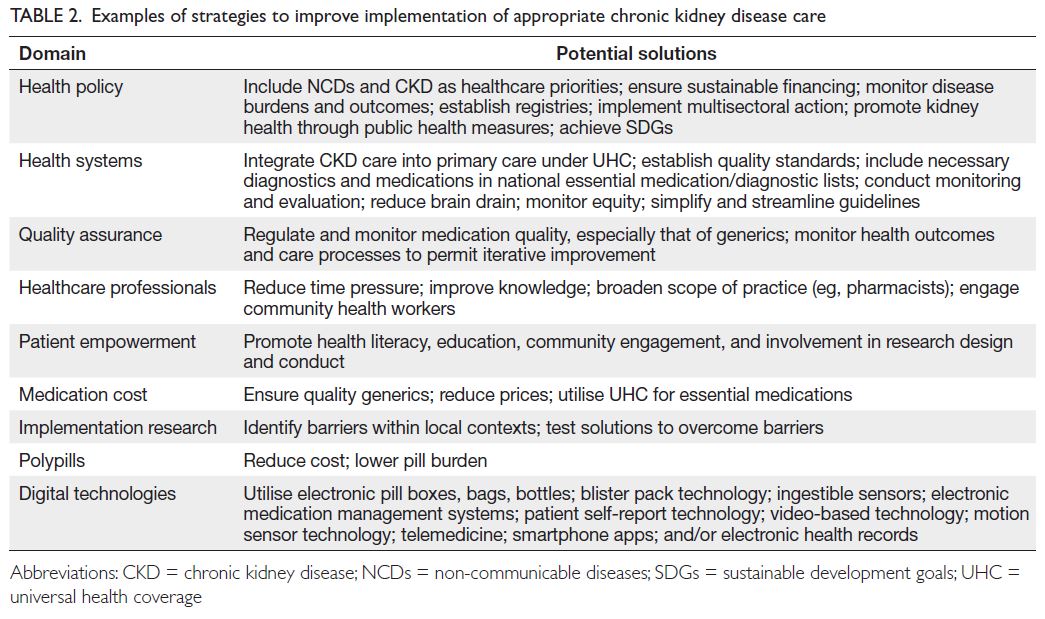

14 It is concerning that CKD awareness

is particularly low among individuals with kidney

dysfunction, such that approximately 80% to 95%

of such patients worldwide are unaware of their

diagnosis (

Fig 2).

15 16 17 18 19 20 Therefore, people are dying

because of missed opportunities to detect CKD early

and deliver optimal care.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Proportion of people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who are aware of their diagnosis and receiving guideline-recommended care. The

proportion of people with CKD who are aware of their diagnosis varies from 7% to 20% worldwide. Knowledge of CKD increases as CKD stage

worsens. Among those with a diagnosis of CKD, the average proportion of patients receiving appropriate medication to delay CKD progression

(renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [RAS] inhibitors and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 [SGLT2] inhibitors) is suboptimal, as are the average

proportions of patients achieving target blood pressure, maintaining diabetes control, and receiving nutrition advice. Treatment targets depicted in the figure follow the 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines.

15 Most data are from higher-resource settings; the corresponding proportions are likely to be lower in lower-resource settings. Data represent the proportions of patients reaching blood pressure <130/80 mm Hg. Data compiled from previous studies

15 16 17 18 19 20

Furthermore, CKD is a major risk factor

for cardiovascular disease; during kidney disease

progression, cardiovascular death and KF become

competing risks.

21 Indeed, data from the 2019

Global Burden of Disease Study showed that more

deaths were caused by kidney dysfunction–related

cardiovascular disease (1.7 million deaths) than

by CKD itself (1.4 million deaths).

2 Therefore, cardiovascular disease management should also be prioritised for people with CKD.

Gaps between knowledge and implementation in kidney care

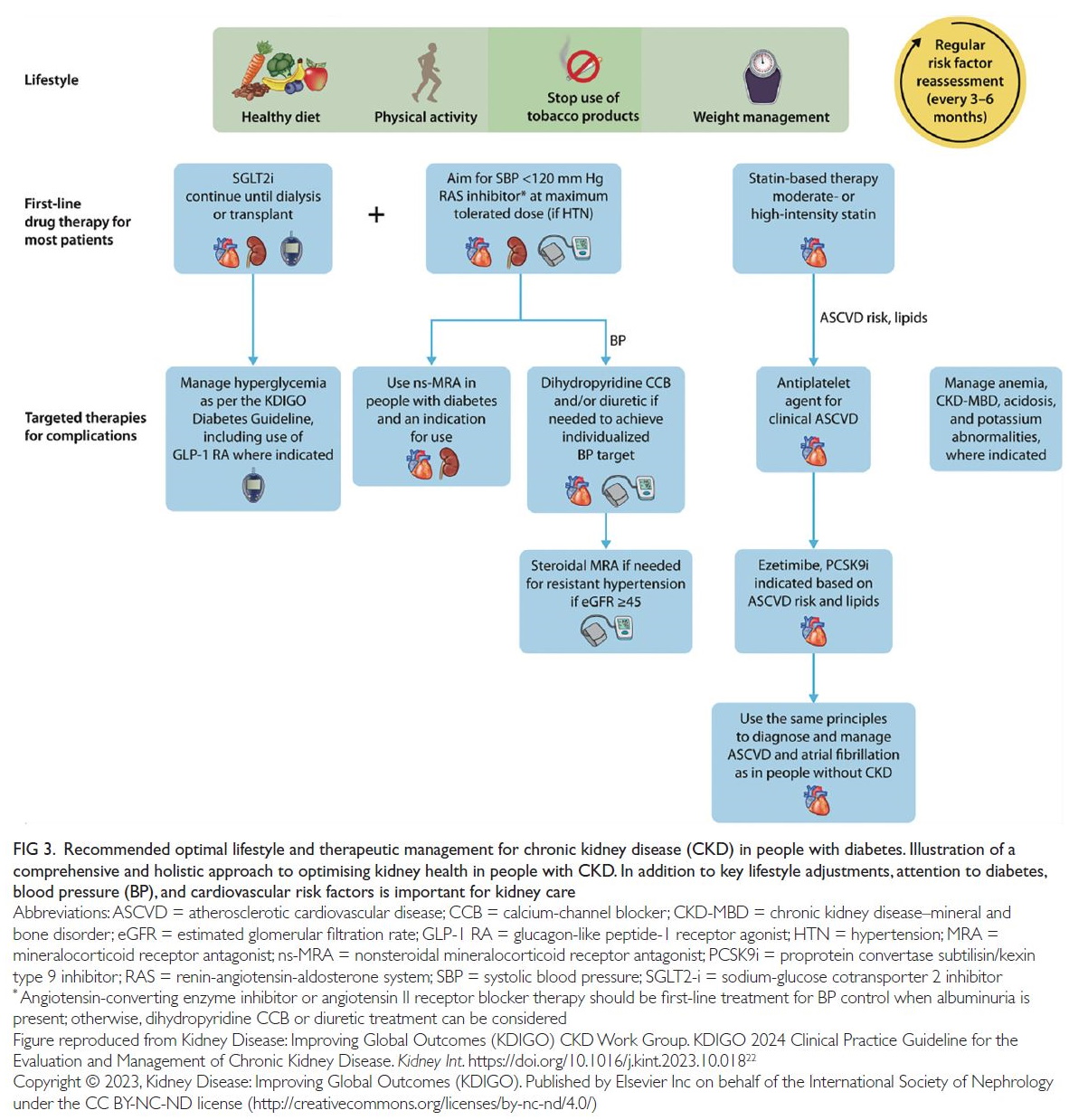

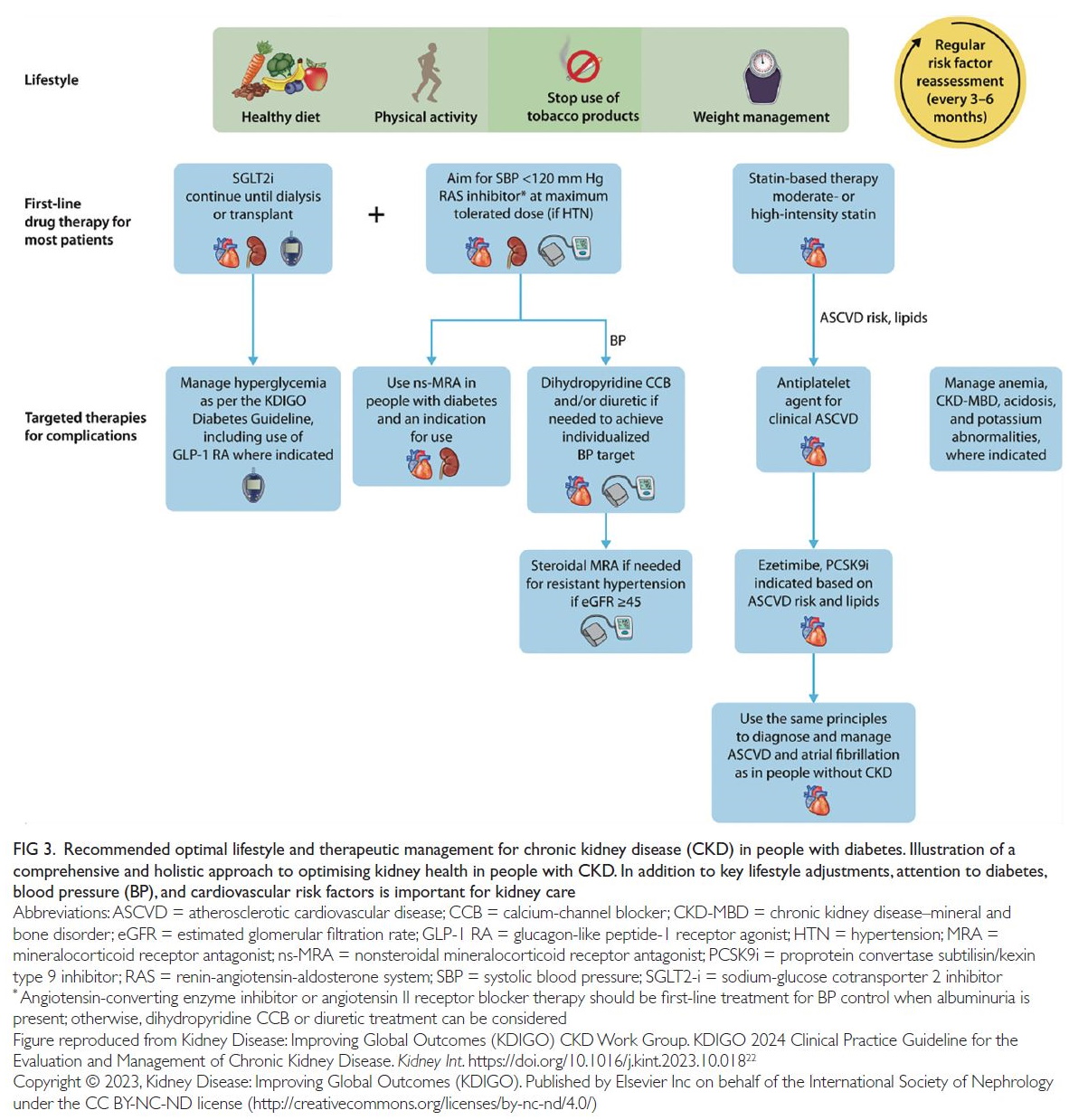

Strategies to prevent and treat CKD have been

established on the basis of strong evidence collected

over the past three decades (

Fig 3).

19 22 Clinical

practice guidelines for CKD are clear; however,

adherence to these guidelines is suboptimal (

Fig 2).

15 19 20

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Recommended optimal lifestyle and therapeutic management for chronic kidney disease (CKD) in people with diabetes. Illustration of a

comprehensive and holistic approach to optimising kidney health in people with CKD. In addition to key lifestyle adjustments, attention to diabetes,

blood pressure (BP), and cardiovascular risk factors is important for kidney care

Regardless of aetiology, management of major

risk factors, particularly diabetes and hypertension,

forms the basis of optimal care for people with

CKD.

19 23 In addition to lifestyle changes and risk

factor control, the earliest pharmacological agents to demonstrate kidney protection were renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in the

form of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers.

14 19

Despite decades of knowledge that these medications

have substantial protective effects on renal and

cardiovascular function in people with CKD, real-world

data from electronic health records show that

their use remains low (

Fig 2). For example, in the

United States, ACEI and angiotensin receptor blocker

utilisation rates ranging from 20% to 40% were

reported ≥15 years after the most recent approval

of these agents for patients with CKD and/or type

2 diabetes.

24 Although more recent data show that

prescribing rates in this population have improved

to 70%, only 40% of such patients continue taking

an ACEI or angiotensin receptor blocker for at least

90 days.

20 These data indicate gaps in prescribing

nephroprotective medication and continuity of care

over time, potentially related to cost, lack of patient

education, polypharmacy, and adverse effects.

25

Although the initial enthusiasm for sodium-glucose

cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors focused on their benefits for diabetes and cardiovascular

disease, unprecedented therapeutic benefits have

also been observed regarding CKD. Relative risk

reduction levels with SGLT2 inhibitors approach

40% for substantial decreases in estimated

glomerular filtration rate, KF, and mortality among

populations with several types of CKD, heart failure,

or elevated cardiovascular disease risk.

26 27 These decreases were observed in addition to benefits from

standard-of-care risk factor management and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. The risks

of heart failure, cardiovascular death, and all-cause

mortality were also reduced in patients with CKD

during SGLT2 inhibitor treatment.

26 The addition of

SGLT2 inhibitors to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone

system inhibitor–based treatment was able to delay the need for renal replacement therapy by several

years, depending on the initial timing of combined

treatment.

28 Moreover, for every 1000 patients with

CKD who received an SGLT2 inhibitor in addition to

standard therapy, 83 deaths, 19 heart failure–related

hospitalisations, 51 instances of dialysis initiation,

and 39 episodes of acute renal function worsening

were prevented.

29

The persistent underuse of these and other

guideline-recommended therapies involving SGLT2

inhibitors is concerning (

Fig 2).

20 24 In the CURE-CKD

(Center for Kidney Disease Research, Education and

Hope–CKD) Registry, only 5% and 6.3% of eligible

patients with CKD and diabetes, respectively,

continued to receive SGLT2 inhibitor and glucagon-like

peptide-1 receptor agonist therapy at 90 days.

18

Notably, a lack of commercial health insurance and

the receipt of treatment in community-based (versus

academic) institutions were associated with lower

likelihoods of SGLT2 inhibitor, ACEI, or angiotensin

receptor blocker prescriptions among patients with

CKD and diabetes.

20 In low- or middle-income

countries (LMICs), the gap between evidence and

implementation is even wider, considering the

high cost and inconsistent availability of these

medications, although generics are available.

30

Such gaps in delivering optimal care for CKD are

unacceptable.

In addition to SGLT2 inhibitors, nonsteroidal

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists have been

demonstrated to reduce the risks of CKD progression,

KF, cardiovascular events, and mortality, when used

in addition to standard-of-care treatment involving

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors,

among people with type 2 diabetes.

31 There is a

growing portfolio of promising therapeutic options,

including glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

(NCT03819153, NCT04865770), aldosterone

synthase inhibitors (NCT05182840), and dual-to-triple

incretins (

online supplementary Table 1).

26 32

Furthermore, there is clear evidence that in patients

with CKD and/or type 2 diabetes, glucagon-like

peptide-1 receptor agonists reduce cardiovascular

events, constitute safe and effective glucose-lowering

therapies, and aid in weight loss.

32

Historically, it has taken an average of 17 years

for new treatments to move from clinical evidence

to routine practice.

33 Considering that millions of

people with CKD die each year, this waiting period

is far too long.

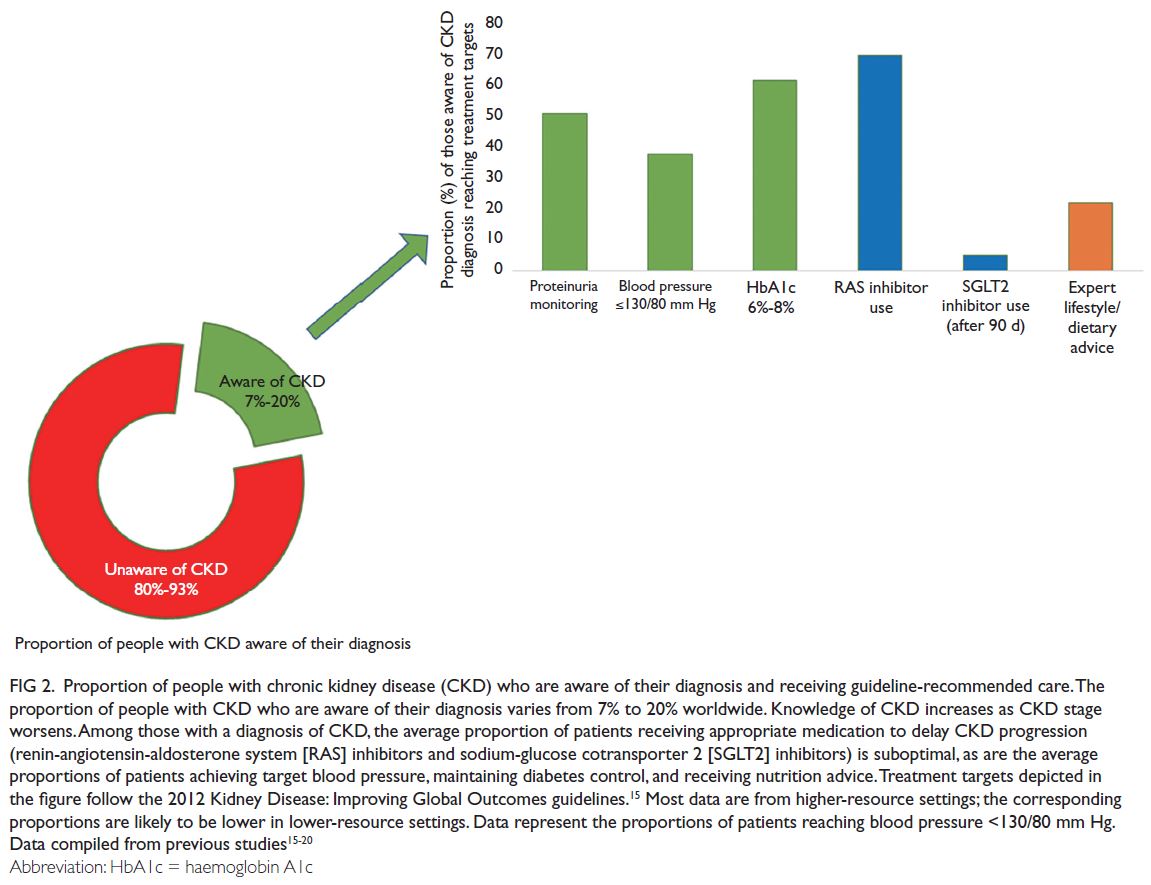

Closing the ‘gap’ between what we know and what we do

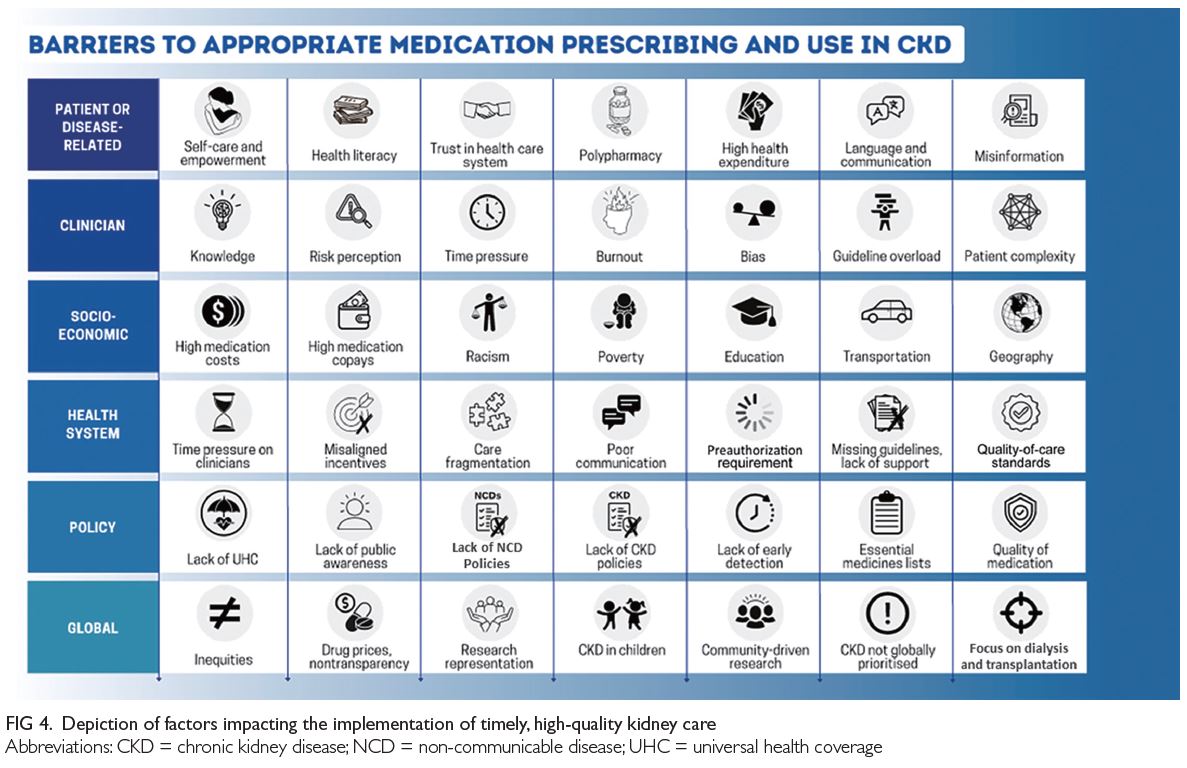

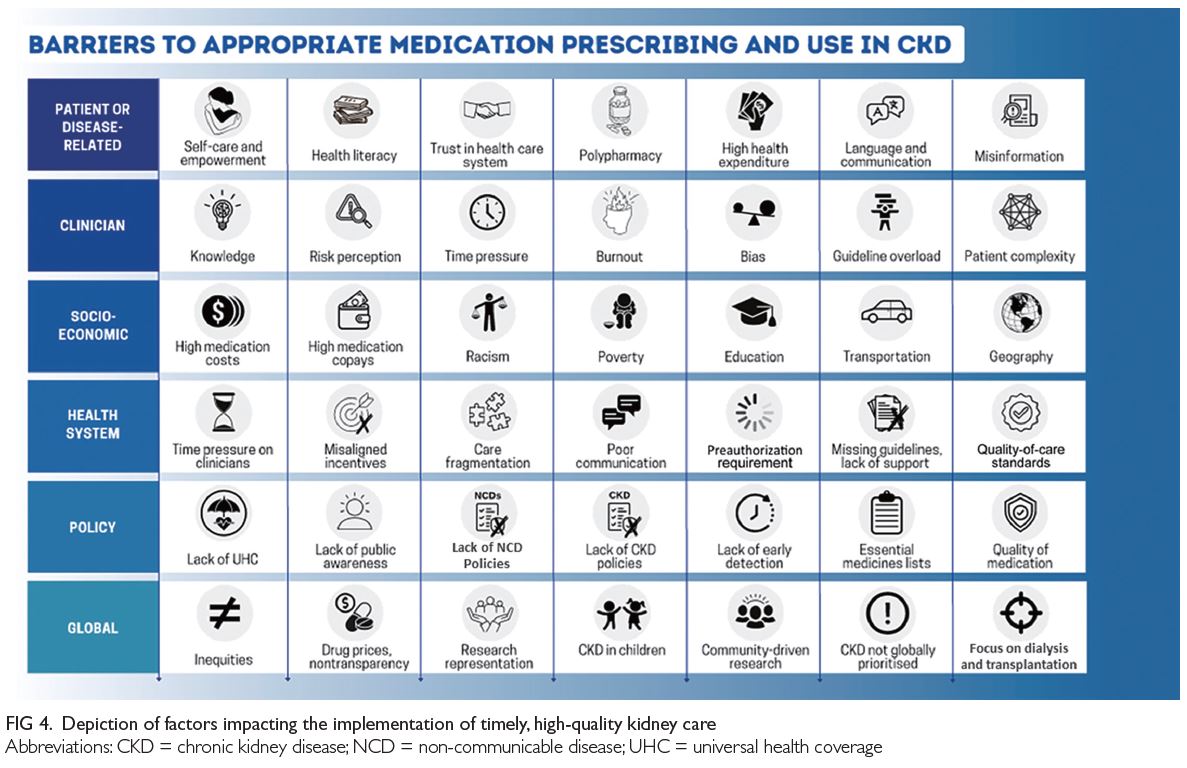

Lack of policy and presence of global inequity

Health policy

Since the launch of the World Health Organization Global Action Plan for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in 2013, there has

been global progress in the proportion of countries

with a national NCD action plan and dedicated NCD

units.

34 However, CKD is incorporated into NCD

strategies in approximately one-half of countries.

4

Policies are required to integrate kidney care within

essential health packages under universal health

coverage (

Fig 4).

30 Multisectoral policies must also

address social determinants of health, which are

major amplifiers of CKD risk and severity that limit

people’s opportunities to improve their health.

3 A

lack of investment in kidney health promotion, along

with primary and secondary prevention of kidney

diseases, hinders progress.

14

Figure 4.

Figure 4. Depiction of factors impacting the implementation of timely, high-quality kidney care

Health systems

Two major goals of universal health coverage are to

achieve coverage for essential health services and to

reduce financial hardship imposed by healthcare.

However, universal health coverage alone is

insufficient to ensure adequate access to kidney care.

3

Health systems must be strengthened, and quality

of care must be prioritised, because poor quality

care contributes to more deaths than lack of access

in low-resource settings.

35 Quality care requires a

well-trained healthcare workforce, sustainable

availability of accurate diagnostics, reliable

infrastructure, and medication supplies; it should

be monitored through a continuous quality

improvement process (

Fig 4). Medication quality,

especially in LMICs, may be an additional barrier

to successful management of CKD.

36 Regulation

and monitoring of drug manufacturing and quality

standards are important to ensure safe and effective

therapies. Strategies to support regulation and

quality assurance should be developed according

to local circumstances and guidelines, as outlined

elsewhere.

37

The establishment of a credible case for CKD

detection and management based on real-world data

regarding risks, interventions, outcomes, and costs

will help translate theoretical cost-effectiveness

(currently established primarily in high-income

countries with minimal data from other countries)

into economic reality.

30 38 Screening should include

evaluation of risk factors for CKD; identification of

family history; recognition of potential symptoms

(usually advanced, such as fatigue, poor appetite,

oedema, and itching); and measurements of blood

pressure, serum creatinine, urine components (ie,

urinalysis), and urine albumin/protein to creatinine

ratio, as outlined in established guidelines.

19 39 Early

identification of CKD in primary care is expected to

lower costs over time by reducing CKD complications

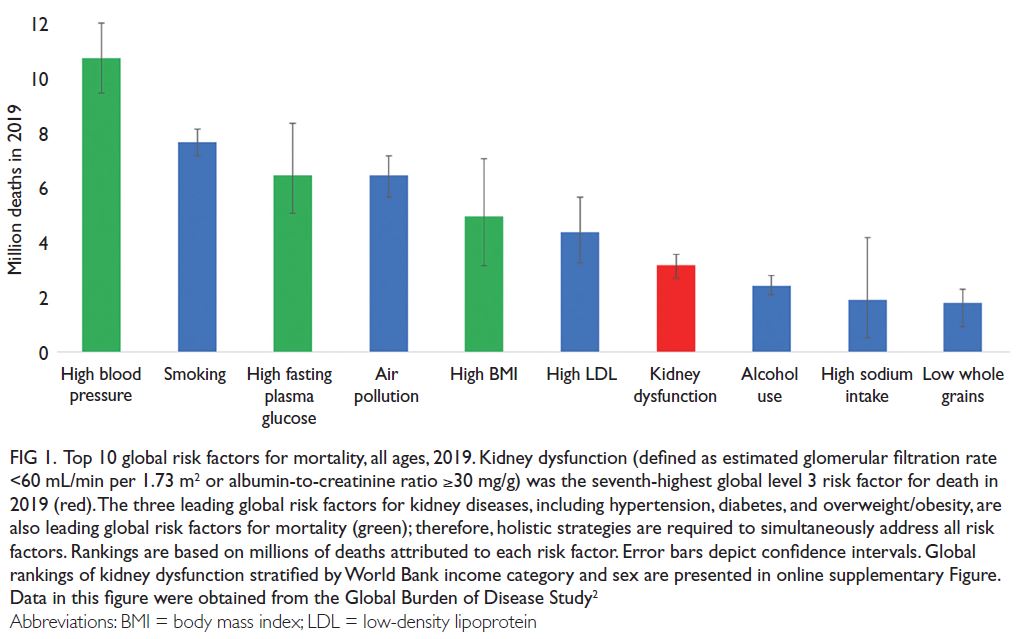

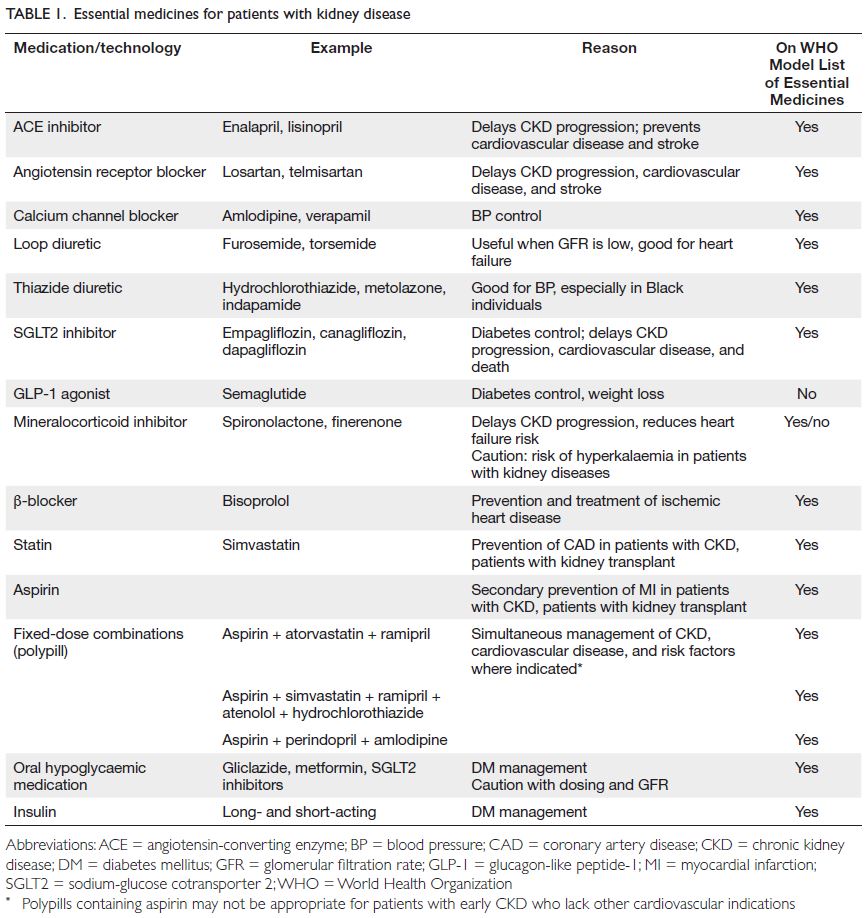

and KF. Medications required for kidney care are

already included in the World Health Organization

Model List of Essential Medicines (

Table 1). These

medications should be provided at the national level under universal health coverage.

40 Additionally, pharmaceutical companies should provide these medications at affordable prices.

Table 1.

Table 1. Essential medicines for patients with kidney disease

Challenges in primary care and clinical inertia

Healthcare professionals

The shortage of primary care professionals is

exacerbated by inconsistent access to specialists

and allied health professionals in both high-income

countries and LMICs. It is essential to define roles

and responsibilities for kidney care. Solutions

may include multidisciplinary team care (primary

care physicians, pharmacists, specialists, nurses,

therapists, educators, nutritionists, and mental

health professionals), well-established mechanisms

for collaboration among all elements, and rapid

communication technologies (both within health

systems and among health professionals) to support

care and decision-making.

41 42 Brain drain in low-resource

settings is a complex issue that must be

addressed.

The mobilisation of community health workers

yields cost-savings in infectious disease programmes within LMICs; it may facilitate early detection,

diagnosis, and management of NCDs.

43 Protocolised

CKD management, possibly assisted by electronic

decision-support systems, may be appropriate for

interventions at the community level, with the

integration of primary care physicians and aid

from nephrologists and other professionals.

44 45 For

example, in some settings, pharmacists could identify

people with diabetes or hypertension exhibiting CKD

risk, based on their prescriptions, then offer on-site

testing and referral as needed.

46 Pharmacists could

also provide medication reconciliation and advice

regarding safety, effectiveness, and adherence. Social

workers and pharmacists can help patients with

medications to access suitable programmes.

46

Clinical inertia

Clinical ‘inertia’, commonly regarded as a causative

factor in low prescribing rates, has many facets (

Fig 4).

47 Many knowledge gaps regarding CKD exist among primary care physicians.

48 Such gaps can

be remedied with focused public and professional

education. Additional factors include fear of adverse

effects from medication, misaligned incentives within the health system, excessive workload, formulary

restrictions, and clinician burnout.

47 Furthermore,

inconsistent recommendations in guidelines from

different professional organisations may enhance

confusion. A major barrier to optimal care is the

time constraints imposed on individual clinicians. A

typical primary care physician in the United States

would require approximately 26.7 hours per day

to implement guideline-recommended care for a

panel of 2500 patients.

49 Innovation is required to

support guideline implementation, especially for

primary care physicians who must follow multiple

guidelines to meet the diverse needs of their patients.

Electronic health records, reminders, team-based nudges, and decision-support tools offer potentially

valuable assistance for quality kidney care in busy

clinical practices.

50 However, the additional time

and effort involved in negotiating pre-authorisations

or completing medication assistance programme

requests, as well as the need for frequent monitoring

of multiple medications, also hinder appropriate

prescribing.

25 Many primary care physicians only

have a few minutes allocated for each patient because

of institutional pressure or patient volume. The term

‘inertia’ can hardly be applied to clinicians working

at this pace. The number of health professionals

worldwide must increase.

Visits for patients with CKD are complex because multimorbidity is common. Such patients are often managed by multiple specialists, leading

to fragmentation of care, lack of holistic oversight,

and diffusion of responsibility for treatment. Single

and combined outcomes analyses have shown that

multidisciplinary care improves transition to renal

replacement therapy and reduces mortality.

51 Novel

‘combined clinic’ models with on-site collaboration

and joint participation (eg, with nephrologists,

cardiologists, and endocrinologists) may provide

substantial benefits for patients in terms of reduced

fragmentation of care, logistics, and cost savings.

Patient centeredness

Health literacy

Self-management is the most important aspect of

kidney care. A patient’s ability to understand his/her health needs, make healthy choices, feel safe

and respected in the health system, and obtain

psychosocial support are important for promoting

health decision-making (

Fig 4). Good communication

should begin with quality information and

confirmation of ‘understanding’ by the patient (and

family members, as applicable). Electronic apps and

reminders can serve as useful tools that support

patients by improving disease knowledge, promoting

patient empowerment, and improving self-efficacy;

however, a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to

be successful.

52 Important barriers include a lack of

patient health information, poor communication,

and mistrust, especially in the marginalised and

minoritised communities where CKD is common.

30

Patients may also be confused by contradictory

recommendations among healthcare professionals,

as well as conflicting messages in mainstream media.

Innovative platforms that improve CKD-related

communication between patients and clinicians

represent a promising approach to promote optimal

prescribing and adherence.

53 54

Patient perspectives are essential when

designing and testing health strategies to overcome

barriers and promote equity. Collaborative care

models must include patients, families, and

community groups, as well as various types

of healthcare professionals, health systems,

government agencies, and payers.

38 Advocacy organisations, local community groups, and peer

navigators with trusted voices and relationships

can serve as conduits for education while providing

input regarding the development of patient tools and

outreach programmes.

55 Most importantly, patients

must be the focus of their own care.

Medication cost and availability

In high-income countries, people without health insurance and people with high copays paradoxically

pay the highest amounts for essential and non-essential nonessential

medications.

38 Across LMICs, kidney

diseases represent the leading cause of catastrophic

health expenditures due to reliance on out-of-pocket

payments.

56 In 18 countries, four cardiovascular

disease medications frequently indicated in CKD

(statins, ACEIs, aspirin, and β-blockers) had greater

availability in private settings than in public settings;

they were mostly unavailable in rural communities,

and they were unaffordable for 25% of people in

upper middle-income countries and 60% of people

in low-income countries.

57 Newer therapies may be

prohibitively expensive worldwide, especially where

generics are not yet available. In the United States,

the retail price for a 1-month supply of an SGLT2

inhibitor or finerenone is approximately US$500

to $700; for glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor

agonists, the retail price is approximately US$800 to

$1200 per month.

38 This reliance on out-of-pocket

payments for vital, life-saving essential medications

is unacceptable (

Fig 4).

Special considerations

Not all kidney diseases are equal. Much of what

has been discussed here applies to the most

common forms of CKD (eg, diabetes-related

and hypertension-related). Some incompletely

understood forms of CKD have different risk

profiles, including environmental exposures, genetic

predisposition, and autoimmune or other systemic

disorders. Highly specialised therapies may be

required. Pharmaceutical companies should be

responsible for ensuring that research studies include

disease-representative participants with appropriate

representation (eg, race, ethnicity, sex, and gender),

that effective drugs are made available after studies,

and that the balance between profits and prices

is fair and transparent. Many novel therapies are

offering new hope for various kidney diseases; once

these therapies are approved, there must be no delay

in extending benefits to all affected patients (

online supplementary Table 1).

An important but often overlooked group

consists of children with kidney diseases. This group

is especially vulnerable in LMICs, where nephrology

services and resources are limited; families must

often decide whether to pay for one child’s treatment

or support the rest of the family.

58 Children with

CKD also have a high risk of cardiovascular disease,

even in high-income settings, and they require

more attention to control risk factors and achieve

treatment targets.

59

Fostering innovation

Implementation science and knowledge translation

Considering that rigorous evidence-based treatments

for CKD have been established, implementation must be optimised.

60 Implementation research aims

to identify effective solutions by understanding

how evidence-based practices, often developed

in high-income countries, can be integrated into

care pathways in lower-resource settings. The

management of CKD is suitable for implementation

research: optimal therapeutic strategies are known,

outcomes are easily measurable, and essential

diagnostics and medications already are in place.

Crucial components of such research are the

identification of local patient preferences and

elucidation of challenges. Ministries of health should

commit to overcoming identified barriers and scaling

up successful and sustainable programmes.

Polypills as an example of simple innovation

Polypills are attractive on multiple levels: fixed doses

of several guideline-recommended medications are

present within a single tablet (

Table 1), the price is

low, the pill burden is reduced, and the regimen is

simple.

61 Polypills can prevent cardiovascular disease

and are cost-effective for patients with CKD.

62 More

studies are needed, but considering the alternatives

of costly renal replacement therapy or premature

death, it is likely that polypills will be a cost-effective

approach for reducing CKD progression.

Harnessing digital technologies

The integration of telehealth and other types of

remotely delivered care can improve efficiency

and reduce costs.

63 Electronic health records and

registries can support monitoring of quality of care

and identify gaps to guide implementation and

improve outcomes within an evolving health system

that is capable of learning. Artificial intelligence

may also be harnessed to stratify risk, personalise

medication prescribing, and facilitate adherence.

64

The use of telenephrology for communication

between primary care physicians and specialists may

also be beneficial for patient care.

65

Patient perspectives

Multiple methods can support the identification

of patient preferences for CKD care, including

interviews, focus groups, surveys, discrete

choice experiments, structured tools, and simple

conversations.

66 67 Many of these methods are

currently in the research phase. Clinical translation

will require contextualisation and assessments of

local and individual acceptability.

The journey of each person living with CKD is

unique; however, common challenges and barriers

exist. As examples of lived experiences, comments

collected from patients about their medications and

care are detailed in

online supplementary Table 2.

These voices must be heard and acknowledged to

close gaps and improve the quality of kidney care

worldwide.

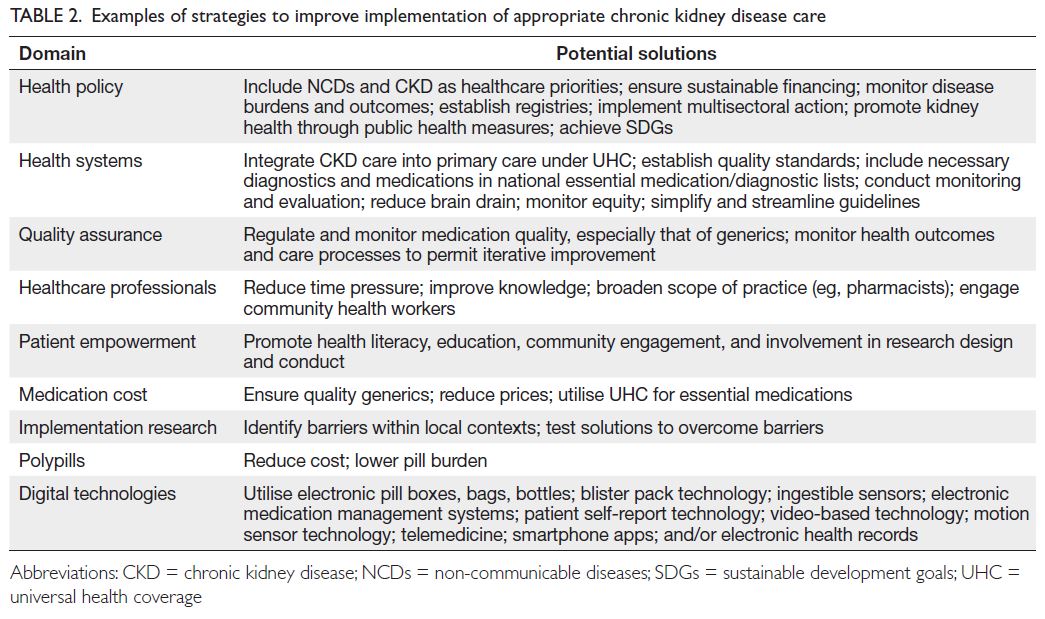

Call to action

The current lack of progress in kidney care has been

tolerated for far too long. New therapeutic advances

offer real hope that many people with CKD can

survive without developing KF. The evidence for

clinical benefit is overwhelming and unequivocal.

These patients cannot wait another 17 years for this

evidence to be translated into clinical practice.

33 It

is time to ensure that all who are eligible for CKD

treatment receive this care in an equitable manner.

Known barriers and global disparities in

access to diagnosis and treatment must be urgently

addressed (

Fig 4). To achieve health equity for

people with kidney diseases and those at risk of

developing kidney diseases, we must raise awareness

among policy makers, patients, and the general

population; harness innovative strategies to support

all cadres of healthcare workers; and balance profits

with reasonable prices (

Table 2). If we narrow the

gap between what we know and what we do, kidney

health will become a reality worldwide.

Table 2.

Table 2. Examples of strategies to improve implementation of appropriate chronic kidney disease care

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception, preparation, and drafting of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

VA Luyckx is chair of the Advocacy Working Group of the

International Society of Nephrology and has no financial

disclosures. KR Tuttle has received research grants from the

National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Diabetes

and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Heart, Lung, and

Blood Institute, National Center for Advancing Translational

Sciences, National Institute on Minority Health and Health

Disparities, director’s office), the United States Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, and Travere Therapeutics;

and consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer

Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. She is also chair of

the Diabetic Kidney Disease Collaborative for the American

Society of Nephrology. R Correa-Rotter is a member of the

Steering Committee for World Kidney Day, a member of

the Diabetes Committee of the Latin American Society of

Nephrology and Hypertension, and a member of the Latin

American Regional Board of the International Society of

Nephrology. He is also a member of the Steering Committees

for the Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in

Chronic Kidney Disease (DAPA-CKD) trial (AstraZeneca),

the Study Of diabetic Nephropathy with AtRasentan (SONAR)

[AbbVie], A Non-interventional Study Providing Insights Into

the Use of Finerenone in a Routine Clinical Setting (FINE-REAL)

[Bayer], and CKD-ASI (Boehringer Ingelheim). He has

received research grants from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline,

Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk, as well

as speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer

Ingelheim, and Amgen. All other authors have declared no

competing interests.

Funding/support

This editorial received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration

This article was published in Kidney International (Luyckx VA, Tuttle KR, Abdellatif D, et al. Mind the gap in kidney care: translating what we know into what we do. Kidney Int

2024;105:406-17.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2023.12.003), and was reprinted concurrently in several journals. The articles cover identical concepts and wording, but vary in

minor stylistic and spelling changes, detail, and length of

manuscript in keeping with each journal’s style. Any of these

versions may be used in citing this article.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors

and some information may not have been peer-reviewed.

Accepted supplementary material will be published as

submitted by the authors, without any editing or formatting.

Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely

those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong

Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical

Association. The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the

Hong Kong Medical Association disclaim all liability and

responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Jager KJ, Kovesdy C, Langham R, Rosenberg M,

Jha V, Zoccali C. A single number for advocacy and

communication-worldwide more than 850 million

individuals have kidney diseases. Kidney Int 2019;96:1048-50.

Crossref2. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD

compare data visualization. Available from:

http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare. Accessed 18 Nov 2023.

3. Luyckx VA, Tonelli M, Stanifer JW. The global burden of

kidney disease and the sustainable development goals. Bull

World Health Organ 2018;96:414-22D.

Crossref4. International Society of Nephrology. ISN Global Kidney Health Atlas, 3rd ed. Available from:

https://www.theisn.org/initiatives/global-kidney-health-atlas/. Accessed 18 Nov 2023.

5. GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global,

regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease,

1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of

Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020;395:709-33.

Crossref6. Vanholder R, Annemans L, Brown E, et al. Reducing the

costs of chronic kidney disease while delivering quality

health care: a call to action. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017;13:393-409.

Crossref7. Nguyen-Thi HY, Le-Phuoc TN, Tri Phat N, et al. The

economic burden of chronic kidney disease in Vietnam.

Health Serv Insights 2021;14:11786329211036011.

Crossref8. United States Renal Data System. Healthcare expenditures

for persons with CKD. Available from:

https://usrds-adr.niddk.nih.gov/2023/chronic-kidney-disease/6-healthcare-expenditures-

for-persons-with-ckd. Accessed 18 Nov 2023.

9. Kidney Health Australia. Changing the chronic kidney

disease landscape: the economic benefits of early detection

and treatment. Available from:

https://kidney.org.au/uploads/resources/Changing-the-CKD-landscape-Economic-benefits-of-early-detection-and-treatment.pdf. Accessed 16 Jan 2024.

10. Ke C, Liang J, Liu M, Liu S, Wang C. Burden of chronic

kidney disease and its risk-attributable burden in 137

low-and middle-income countries, 1990-2019: results from

the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMC Nephrol

2022;23:17.

Crossref11. Gregg EW, Buckley J, Ali MK, et al. Improving health outcomes of people with diabetes: target setting for the WHO Global Diabetes Compact. Lancet 2023;401:1302-12.

Crossref12. Geldsetzer P, Manne-Goehler J, Marcus ME, et al. The

state of hypertension care in 44 low-income and middle-income

countries: a cross-sectional study of nationally

representative individual-level data from 1.1 million adults.

Lancet 2019;394:652-62.

Crossref13. Chu L, Bhogal SK, Lin P, et al. AWAREness of diagnosis

and treatment of chronic kidney disease in adults with

type 2 diabetes (AWARE-CKD in T2D). Can J Diabetes

2022;46:464-72.

Crossref14. Levin A, Tonelli M, Bonventre J, et al. Global kidney health

2017 and beyond: a roadmap for closing gaps in care,

research, and policy. Lancet 2017;390:1888-917.

Crossref15. Stengel B, Muenz D, Tu C, et al. Adherence to the Kidney

Disease: Improving Global Outcomes CKD guideline in

nephrology practice across countries. Kidney Int Rep

2020;6:437-48.

Crossref16. Chu CD, Chen MH, McCulloch CE, et al. Patient

awareness of CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis

of patient-oriented questions and study setting. Kidney

Med 2021;3:576-85.e1.

Crossref17. Ene-Iordache B, Perico N, Bikbov B, et al. Chronic kidney

disease and cardiovascular risk in six regions of the world

(ISN-KDDC): a cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob Health

2016;4:e307-19.

Crossref18. Gummidi B, John O, Ghosh A, et al. A systematic study of

the prevalence and risk factors of CKD in Uddanam, India.

Kidney Int Rep 2020;5:2246-55.

Crossref19. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)

Diabetes Work Group. KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice

Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney

Disease. Kidney Int 2022;102(5S):S1-127.

Crossref20. Nicholas SB, Daratha KB, Alicic RZ, et al. Prescription

of guideline-directed medical therapies in patients with

diabetes and chronic kidney disease from the CURE-CKD

Registry, 2019-2020. Diabetes Obes Metab 2023;25:2970-9.

Crossref21. Grams ME, Yang W, Rebholz CM, et al. Risks of adverse

events in advanced CKD: the Chronic Renal Insufficiency

Cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis 2017;70:337-46.

Crossref22. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)

CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice

Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic

Kidney Disease. Kidney Int 2024;105(4S):S117-314.

Crossref23. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)

Blood Pressure Work Group. KDIGO 2021 Clinical

Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure

in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int 2021;99(3S):S1-87.

Crossref24. Tuttle KR, Alicic RZ, Duru OK, et al. Clinical characteristics

of and risk factors for chronic kidney disease among adults

and children: an analysis of the CURE-CKD Registry.

JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1918169.

Crossref25. Ismail WW, Witry MJ, Urmie JM. The association between

cost sharing, prior authorization, and specialty drug

utilization: a systematic review. J Manag Care Spec Pharm

2023;29:449-63.

Crossref26. Heerspink HJ, Vart P, Jongs N, et al. Estimated lifetime

benefit of novel pharmacological therapies in patients with

type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: a joint analysis

of randomized controlled clinical trials. Diabetes Obes

Metab 2023;25:3327-36.

Crossref27. Nuffield Department of Population Health Renal Studies

Group; SGLT2 inhibitor Meta-Analysis Cardio-Renal

Trialists' Consortium. Impact of diabetes on the effects

of sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors on kidney

outcomes: collaborative meta-analysis of large placebo-controlled

trials. Lancet 2022;400:1788-801.

Crossref28. Fernández-Fernandez B, Sarafidis P, Soler MJ, Ortiz A.

EMPA-KIDNEY: expanding the range of kidney protection

by SGLT2 inhibitors. Clin Kidney J 2023;16:1187-98.

Crossref29. McEwan P, Boyce R, Sanchez JJ, et al. Extrapolated longer-term

effects of the DAPA-CKD trial: a modelling analysis.

Nephrol Dial Transplant 2023;38:1260-70.

Crossref30. Vanholder R, Annemans L, Braks M, et al. Inequities

in kidney health and kidney care. Nat Rev Nephrol

2023;19:694-708.

Crossref31. Agarwal R, Filippatos G, Pitt B, et al. Cardiovascular and

kidney outcomes with finerenone in patients with type 2

diabetes and chronic kidney disease: the FIDELITY pooled

analysis. Eur Heart J 2022;43:474-84.

Crossref32. Tuttle KR, Bosch-Traberg H, Cherney DZ, et al. Post hoc

analysis of SUSTAIN 6 and PIONEER 6 trials suggests that

people with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk

treated with semaglutide experience more stable kidney

function compared with placebo. Kidney Int 2023;103:772-81.

Crossref33. Rubin R. It takes an average of 17 years for evidence to

change practice—the burgeoning field of implementation

science seeks to speed things up. JAMA 2023;329:1333-6.

Crossref34. World Health Organization. Mid-point evaluation of the

implementation of the WHO global action plan for the

prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases

2013-2020 (NCD-GAP). Volume 1: Report. 2020. Available

from:

https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/about-us/evaluation/ncd-gap-final-report.pdf?sfvrsn=55b22b89_5&download=true. Accessed 18 Nov 2023.

35. Kruk ME, Gage AD, Joseph NT, Danaei G, García-Saisó S,

Salomon JA. Mortality due to low-quality health systems in

the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of

amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet 2018;392:2203-12.

Crossref36. Kingori P, Peeters Grietens K, Abimbola S, Ravinetto R.

Uncertainties about the quality of medical products

globally: lessons from multidisciplinary research. BMJ

Glob Health 2023;6(Suppl 3):e012902.

Crossref37. Pan American Health Organization. Quality control of

medicines. Available from:

https://www.paho.org/en/topics/quality-control-medicines. Accessed 18 Nov 2023.

38. Tuttle KR, Wong L, St Peter W, et al. Moving from evidence

to implementation of breakthrough therapies for diabetic

kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2022;17:1092-103.

Crossref39. Kalyesubula R, Conroy AL, Calice-Silva V, et al. Screening

for kidney disease in low- and middle-income countries.

Semin Nephrol 2022;42:151315.

Crossref40. Francis A, Abdul Hafidz MI, Ekrikpo UE, et al. Barriers to

accessing essential medicines for kidney disease in low- and

lower middle-income countries. Kidney Int 2022;102:969-73.

Crossref41. Rangaswami J, Tuttle K, Vaduganathan M. Cardio-renal-metabolic care models: toward achieving effective

interdisciplinary care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes

2020;13:e007264.

Crossref42. Neumiller JJ, Alicic RZ, Tuttle KR. Overcoming barriers to implementing new therapies for diabetic kidney disease: lessons learned. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2021;28:318-27.

Crossref43. Mishra SR, Neupane D, Preen D, Kallestrup P, Perry HB.

Mitigation of non-communicable diseases in developing

countries with community health workers. Global Health

2015;11:43.

Crossref44. Joshi R, John O, Jha V. The potential impact of public health

interventions in preventing kidney disease. Semin Nephrol

2017;37:234-44.

Crossref45. Patel A, Praveen D, Maharani A, et al. Association of

multifaceted mobile technology-enabled primary care

intervention with cardiovascular disease risk management

in rural Indonesia. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:978-86.

Crossref46. Ardavani A, Curtis F, Khunti K, Wilkinson TJ. The effect

of pharmacist-led interventions on the management and

outcomes in chronic kidney disease (CKD): a systematic

review and meta-analysis protocol. Health Sci Rep

2023;6:e1064.

Crossref47. Sherrod CF, Farr SL, Sauer AJ. Overcoming treatment

inertia for patients with heart failure: how do we build

systems that move us from rest to motion? Eur Heart J

2023;44:1970-2.

Crossref48. Ramakrishnan C, Tan NC, Yoon S, et al. Healthcare

professionals’ perspectives on facilitators of and barriers to

CKD management in primary care: a qualitative study in

Singapore clinics. BMC Health Serv Res 2022;22:560.

Crossref49. Porter J, Boyd C, Skandari MR, Laiteerapong N. Revisiting

the time needed to provide adult primary care. J Gen

Intern Med 2023;38:147-55.

Crossref50. Peralta CA, Livaudais-Toman J, Stebbins M, et al.

Electronic decision support for management of CKD in

primary care: a pragmatic randomized trial. Am J Kidney

Dis 2020;76:636-44.

Crossref51. Rios P, Sola L, Ferreiro A, et al. Adherence to

multidisciplinary care in a prospective chronic kidney

disease cohort is associated with better outcomes. PLoS

One 2022;17:e0266617.

Crossref52. Stevenson JK, Campbell ZC, Webster AC, et al. eHealth

interventions for people with chronic kidney disease.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;8:CD012379.

Crossref53. Tuot DS, Crowley ST, Katz LA, et al. Usability testing of the

kidney score platform to enhance communication about

kidney disease in primary care settings: qualitative think-aloud

study. JMIR Form Res 2022;6:e40001.

Crossref54. Verberne WR, Stiggelbout AM, Bos WJ, van Delden JJ.

Asking the right questions: towards a person-centered

conception of shared decision-making regarding treatment

of advanced chronic kidney disease in older patients. BMC

Med Ethics 2022;23:47.

Crossref55. Taha A, Iman Y, Hingwala J, et al. Patient navigators for CKD and kidney failure: a systematic review. Kidney Med

2022;4:100540.

Crossref56. Essue BM, Laba TL, Knaul F, et al. Economic burden

of chronic ill health and injuries for households in low- and

middle-income countries. In: Jamison DT, Gelband

H, Horton S, et al, editors. Disease Control Priorities:

Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. 3rd ed. The

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2017: 121-43.

Crossref57. Khatib R, McKee M, Shannon H, et al. Availability and

affordability of cardiovascular disease medicines and their

effect on use in high-income, middle-income, and low-income

countries: an analysis of the PURE study data.

Lancet 2016;387:61-9.

Crossref58. Kamath N, Iyengar AA. Chronic kidney disease (CKD):

an observational study of etiology, severity and burden of

comorbidities. Indian J Pediatr 2017;84:822-5.

Crossref59. Cirillo L, Ravaglia F, Errichiello C, Anders HJ, Romagnani P,

Becherucci F. Expectations in children with glomerular

diseases from SGLT2 inhibitors. Pediatr Nephrol

2022;37:2997-3008.

Crossref60. Donohue JF, Elborn JS, Lansberg P, et al. Bridging the

“know-do” gaps in five non-communicable diseases using

a common framework driven by implementation science. J

Healthc Leadersh 2023;15:103-19.

Crossref61. Population Health Research Institute. Polypills added

to WHO essential medicines list. 2023. Available from:

https://www.phri.ca/eml/". Accessed 18 Nov 2023.

62. Sepanlou SG, Mann JF, Joseph P, et al. Fixed-dose

combination therapy for prevention of cardiovascular

diseases in CKD: an individual participant data meta-analysis.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2023;18:1408-15.

Crossref63. Dev V, Mittal A, Joshi V, et al. Cost analysis of telemedicine

use in paediatric nephrology–the LMIC perspective.

Pediatr Nephrol 2024;39:193-201.

Crossref64. Musacchio N, Zilich R, Ponzani P, et al. Transparent

machine learning suggests a key driver in the decision to

start insulin therapy in individuals with type 2 diabetes. J

Diabetes 2023;15:224-36.

Crossref65. Zuniga C, Riquelme C, Muller H, Vergara G, Astorga C,

Espinoza M. Using telenephrology to improve access to

nephrologist and global kidney management of CKD

primary care patients. Kidney Int Rep 2020;5:920-3.

Crossref66. van der Horst DE, Hofstra N, van Uden-Kraan CF, et al.

Shared decision making in health care visits for CKD:

patients' decisional role preferences and experiences. Am

J Kidney Dis 2023;82:677-86.

Crossref67. Hole B, Scanlon M, Tomson C. Shared decision making: a

personal view from two kidney doctors and a patient. Clin

Kidney J 2023;16(Suppl 1):i12-9.

Crossref