Faculty development for postgraduate medical education in Hong Kong

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

EDITORIAL

Faculty development for postgraduate medical

education in Hong Kong

HY So, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)1; Philip KT Li, FHKAM (Medicine)2; Benny CP Cheng, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)3; Faculty Development Workgroup, Hong Kong Jockey Club Innovative Learning Centre for Medicine#; Gilberto KK Leung, FHKAM (Surgery)4

1 Educationist, Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Vice-President (Education and Examinations), Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Honorary Director, Hong Kong Jockey Club Innovative Learning Centre for Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 President, Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

# Members of Faculty Development Workgroup:

Albert KM Chan (The Hong Kong College of Anaesthesiologists),

Dominic KL Ho (The College of Dental Surgeons of Hong Kong),

Franklin TT She (The College of Dental Surgeons of Hong Kong),

YF Choi (Hong Kong College of Emergency Medicine),

Peter Anthony Fok (The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians),

KK Tang (The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists),

Jason CS Yam (The College of Ophthalmologists of Hong Kong),

PT Chan (The Hong Kong College of Orthopaedic Surgeons),

KC Wong (The Hong Kong College of Otorhinolaryngologists),

SP Wu (Hong Kong College of Paediatricians),

Rock YY Leung (The Hong Kong College of Pathologists),

YM Kan (Hong Kong College of Physicians),

CW Law (The Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists),

Kevin KF Fung (Hong Kong College of Radiologists),

Skyi YC Pang (The College of Surgeons of Hong Kong)

Albert KM Chan (The Hong Kong College of Anaesthesiologists),

Dominic KL Ho (The College of Dental Surgeons of Hong Kong),

Franklin TT She (The College of Dental Surgeons of Hong Kong),

YF Choi (Hong Kong College of Emergency Medicine),

Peter Anthony Fok (The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians),

KK Tang (The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists),

Jason CS Yam (The College of Ophthalmologists of Hong Kong),

PT Chan (The Hong Kong College of Orthopaedic Surgeons),

KC Wong (The Hong Kong College of Otorhinolaryngologists),

SP Wu (Hong Kong College of Paediatricians),

Rock YY Leung (The Hong Kong College of Pathologists),

YM Kan (Hong Kong College of Physicians),

CW Law (The Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists),

Kevin KF Fung (Hong Kong College of Radiologists),

Skyi YC Pang (The College of Surgeons of Hong Kong)

Corresponding author: Dr HY So (sohingyu59@gmail.com)

Competency-based medical education and faculty development

By the late 20th century, traditional teaching methods

in postgraduate medical education were considered

inadequate for preparing doctors to navigate modern

healthcare systems, thereby posing risks to patient

safety. This realisation led to a global shift towards

competency-based medical education.1 2 3 The Hong

Kong Academy of Medicine (HKAM) identifies

seven key competencies essential for contemporary

medical practitioners, namely, professional

expertise, interpersonal communication, teamwork,

leadership, professionalism, academia, and health

promotion. The achievement of proficiency in these

areas requires novel approaches to teaching and

learning.

Traditional postgraduate medical education

is often centred around two main principles: the

transmission of knowledge and the ‘see one, do one,

teach one’ model. Although knowledge acquisition

is essential, mere memorisation of facts and

information does not lead to excellence in medical

practice. Effective education requires more than the

delivery of information. It involves selecting content

aligned with learning objectives, organising and

presenting material in ways that reflect how people

learn, and fostering motivation to engage with the

material.4 It had been demonstrated that knowledge

acquisition alone does not result in expertise.5

Individuals may successfully recall information

and perform well on examinations, but they often

encounter difficulties when addressing real-life clinical problems. The application of knowledge is

critical, and hands-on clinical experience is invaluable.

However, the tasks encountered in postgraduate

medicine are more complex and challenging than

those in traditional apprenticeships, rendering the

‘see one, do one, teach one’ method insufficient.

Teaching methods that provide support and promote

a deeper understanding of material are necessary to

develop true expertise in medicine.6 The importance

of such teaching methods underscores the critical

need for faculty development—commonly referred

to as training for trainers—which involves acquiring

new skills and knowledge while undergoing a shift in

mindset.

The Faculty Development Workgroup

Faculty development is central to the successful

implementation of competency-based medical

education. It includes activities undertaken by

healthcare professionals to enhance teaching,

leadership, research, and scholarly abilities in both

individual and group contexts.7 This emphasis on

faculty development was highlighted in the Position

Paper on Postgraduate Medical Education, published

in 2023.8 The Hong Kong Jockey Club Innovative

Learning Centre for Medicine (ILCM), established

by HKAM, was created to modernise postgraduate

medical education in Hong Kong. Initially focused

on simulation-based medical education, the ILCM

has since broadened its scope to address all aspects of postgraduate medical education.9 Recognising the

importance of faculty development, the ILCM has

assumed a leading role in advocating for this concept

within the medical community. To advance these

efforts, the ILCM formed the Faculty Development

Workgroup (the ‘Workgroup’), which includes

representatives from all 15 Colleges under HKAM,

to collaborate on faculty development initiatives.

To ensure that faculty development in

postgraduate medical education is competency-based,

the Workgroup conducted a literature review

to identify existing frameworks and identified seven

relevant models.10 11 12 13 14 15 16 After careful deliberation, the

frameworks proposed by Hesketh et al12 and the

Academy of Medical Educators16 were deemed the

most comprehensive and appropriate for adaptation

to the local context in Hong Kong.

The Faculty Development Framework of the Academy

Steinert7 defines faculty as all individuals involved

in teaching and educating learners across the

educational continuum (eg, undergraduate,

graduate, postgraduate, and continuing professional

development), leadership and management within

universities, hospitals, and the community, as well

as research and scholarship in the health professions

(eg, communication sciences, dentistry, nursing, and

rehabilitation sciences). Based on this definition, the

Workgroup delineated four categories of faculty

within the framework: trainers, examiners, supervisors

of training, and collegial leads in medical education

within each College of HKAM. The initial phase of

development focused on creating the Framework

for Faculty Development of Trainers, which outlines the key competencies required for trainers. This

framework facilitates the identification of individual

learning needs, supports effective delivery of course

content, and guides the evaluation of outcomes of the

faculty development programme.17

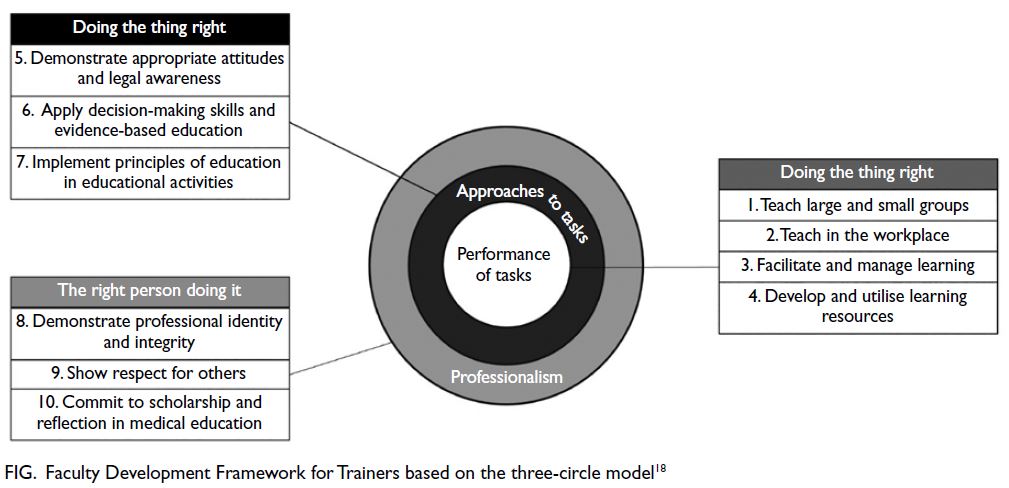

The Workgroup adopted the three-circle model

to classify learning outcomes proposed by Simpson

et al.18 This model categorises competencies into core

tasks, approaches to tasks, and professional identity,

ensuring that trainers perform their roles effectively

while approaching these roles with appropriate

attitudes and professionalism (Fig).18

Workshops and beyond for faculty development

The Framework for Faculty Development of Trainers17

was approved earlier this year by the Education

Committee and the Council of HKAM (Fig). In the

future, the ILCM will design and implement training

workshops guided by the following principles19:

Evidence-informed educational design

Relevant content

Experiential learning with opportunities for practice and application

Opportunities for feedback and reflection

Intentional community building

Moreover, a recent systematic review has

highlighted key principles for effective faculty

development that extend beyond workshops and

individual teaching effectiveness. These principles

include strengthening participants’ identities as

educators, promoting recognition of educational

excellence and leadership development, and fostering

communities of practice to support ongoing learning

and skill refinement.20 This comprehensive approach

reflects the learning process for clinical skills, which requires practice, feedback, and continuous

development in the workplace. Therefore, effective

faculty development will require sustained support

from HKAM and collaboration with stakeholders

across all Colleges to ensure that faculty continue to

advance their skills after completing workshops.

Conclusion

Faculty development is essential for the advancement

of postgraduate medical education in Hong

Kong. By equipping trainers with the appropriate

competencies and skills, the framework ensures that

doctors in training receive high-quality education

and mentorship, ultimately enhancing patient care

and outcomes within the healthcare system.6

Author contributions

All authors have contributed equally to the concept,

development and critical revision of the manuscript. All

authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This editorial received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. To Err Is

Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington (DC):

National Academies Press; 2000.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health

Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health

system for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National

Academies Press (US); 2001.

3. Whitehead CR, Austin Z, Hodges BD. Flower power: the

armoured expert in the CanMEDS competency framework?

Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2011;16:681-94. Crossref

4. Swanwick T, Forrest K, O’Brien BC, editors. Understanding

Medical Education: Evidence, Theory, and Practice. The

Association for the Study of Medical Education (ASME);

2019. Crossref

5. Dreyfus SE, Dreyfus HL. A five-stage model of the mental

activities involved in direct skill acquisition. Operations

Research Center, University of California, Berkeley; 1980.

6. So HY. Postgraduate medical education: see one, do one,

teach one…and what else? Hong Kong Med J 2023;29:104. Crossref

7. Steinert Y. Faculty development: core concepts and principles. In: Steinert Y, editor. Faculty Development in

the Health Professions: A Focus on Research and Practice.

Innovation and Change in Professional Education, 11.

Dordrecht [NY]: Springer; 2014: 3-25. Crossref

8. So HY, Li PK, Lai PB, et al. Hong Kong Academy of Medicine

position paper on postgraduate medical education 2023.

Hong Kong Med J 2023;29:448-52. Crossref

9. Chen PP, So HY, Lo JS, Cheng BC. Modernising

postgraduate medical education: evolving roles of the

Hong Kong Jockey Club Innovative Learning Centre for

Medicine in the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. Hong

Kong Med J 2023;29:480-3. Crossref

10. Skeff KM, Stratos GA, Bergen MR, Regula DP Jr. A pilot

study of faculty development for basic science teachers.

Acad Med 1998;73:701-4. Crossref

11. Harden RM, Crosby J. AMEE Guide No. 20: The good teacher is more than a lecturer—the twelve roles of the teacher. Med Teach 2000;22:334-47. Crossref

12. Hesketh EA, Bagnall G, Buckley EG, et al. A framework

for developing excellence as a clinical educator. Med Educ

2001;35:555-64. Crossref

13. Molenaar WM, Zanting A, van Beukelen P, et al. A

framework of teaching competencies across the medical

education continuum. Med Teach 2009;31:390-6. Crossref

14. Milner RJ, Gusic ME, Thorndyke LE. Perspective:

toward a competency framework for faculty. Acad Med

2011;86:1204-10. Crossref

15. Srinivasan M, Li ST, Meyers FJ, et al. “Teaching as a

Competency”: competencies for medical educators. Acad

Med 2011;86:1211-20. Crossref

16. Academy of Medical Educators. Professional standards for

medical, dental and veterinary educators (fourth edition).

2022. Available from: https://www.medicaleducators.org/write/MediaManager/Documents/AoME_Professional_Standards_4th_edition_1.0_(web_full_single_page_spreads).pdf . Accessed 1 Nov 2024.

17. Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. Framework for

Faculty Development Part 1: Trainers. September 2024.

Available from: https://www.hkam.org.hk/sites/default/files/PDFs/2024/HKAM_Faculty%20Development%20Framework_Part%201.pdf?v=1729586789500. Accessed 20 Sep 2024.

18. Simpson JG, Furnace J, Crosby J, et al. The Scottish

doctor—learning outcomes for the medical undergraduate

in Scotland: a foundation for competent and reflective

practitioners. Med Teach 2002;24:136-43. Crossref

19. Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, et al. A systematic review

of faculty development initiatives designed to improve

teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide

No. 8. Med Teach 2006;28:497-526. Crossref

20. Steinert Y, Mann K, Anderson B, et al. A systematic review

of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance

teaching effectiveness: a 10-year update: BEME Guide No.

40. Med Teach 2016;38:769-86. Crossref