Hong Kong Med J 2025 Apr;31(2):119–29 | Epub 7 Apr 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Mask-wearing intention after the removal of the

mandatory mask-wearing requirement in Hong

Kong: application of the protection motivation

theory and the theory of planned behaviour

Tommy KC Ng, MSc1; Ben YF Fong, MPH, FHKAM (Community Medicine)1; Vincent TS Law, DBA, PMgr2; Pimtong Tavitiyaman, PhD3; WK Chiu, PhD1

1 Division of Science, Engineering and Health Studies, College of

Professional and Continuing Education, Hong Kong Polytechnic

University, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Division of Social Sciences, Humanities and Design, College of

Professional and Continuing Education, Hong Kong Polytechnic

University, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Division of Business and Hospitality Management, College of

Professional and Continuing Education, Hong Kong Polytechnic

University, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Mr Tommy KC Ng (tommy.ng@cpce-polyu.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The mandatory mask-wearing

requirement, which had been in place for nearly

1000 days in Hong Kong, was lifted on 1 March

2023. Little is known about the intention to continue

wearing a mask after the removal of the mandate in

the city. This study aimed to examine predictors of

mask-wearing intention after the mandate was lifted,

using the protection motivation theory (PMT) and

the theory of planned behaviour (TPB).

Methods: A conceptual model was developed to

depict the relationships between the constructs of

PMT and TPB in predicting continued mask-wearing

intention after the removal of the mandate. A cross-sectional

study was conducted using an online

questionnaire from 8 to 20 March 2023. Partial least

squares structural equation modelling was utilised

to examine relationships between the constructs.

Results: In total, 483 responses were included

in the data analysis. Perceived severity (β=0.089;

P=0.017), perceived self-efficacy (β=0.253; P<0.001),

subjective norms (β=0.289; P<0.001), and attitude

(β=0.325; P<0.001) had significant positive effects

on the intention to continue wearing a mask. In

contrast, the perceived reward of maladaptive

behaviours had a significant negative effect on mask-wearing

intention (β=-0.071; P=0.012). Perceived

vulnerability, perceived response efficacy, perceived response cost, and perceived behavioural control

were not significantly associated with mask-wearing

intention.

Conclusion: The findings indicate that attitude

towards continued mask-wearing was the strongest

predictor of mask-wearing intention, followed

by subjective norms and perceived self-efficacy.

Insights from this study may inform public health

policymaking regarding mask-wearing practices in

future health crises.

New knowledge added by this study

- More than half of the respondents (53.6%) consistently wore a mask after the mandatory mask-wearing requirement had been lifted in Hong Kong.

- Attitude towards continued mask-wearing was the strongest predictor of mask-wearing intention, followed by subjective norms and perceived self-efficacy.

- A high frequency of mask-wearing was observed after the mandatory mask-wearing requirement had been lifted. The progress of Hong Kong citizens in returning to pre-pandemic norms requires further evaluation.

- The positive attitude towards mask-wearing among Hong Kong citizens suggests that they are prepared for future health crises.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

has had extensive global social and health impacts.

It triggered an international health and economic

crisis that has profoundly altered people’s lives,

perceptions, and behaviours. As of 13 March 2025, about 778 million confirmed cases of COVID-19

had caused around 7.1 million deaths worldwide.1

Various levels of non-pharmaceutical interventions,

including frequent handwashing, mask-wearing,

and social distancing, were implemented in most

countries.2 These interventions played important roles in reducing community transmission of

COVID-19.3 However, the stringent measures also

led to negative consequences, such as economic

slowdown, disrupted education, and increased social

isolation and psychological stress.4 5 Many countries

lifted non-pharmaceutical interventions while the

number of cases was still increasing. In England,

all COVID-19–related restrictions were lifted on

22 February 2022 under the ‘Living with COVID’

strategy,6 although the number of cases increased

in subsequent months. Australia, Singapore, and

Hong Kong adopted a ‘Zero-COVID’ strategy.7 In

Australia, all mandatory mask-wearing requirements

on public transport were lifted in mid-September

2022.8 Singapore also lifted such requirements on 9 February 2023.9 Hong Kong, a leading international

business and financial centre, finally lifted all

mandatory mask-wearing requirements on 1

March 2023,10 nearly 1000 days after the start of

the pandemic in 2020. Since then, the city has been

transitioning towards the post–COVID-19 era.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many

governments mandated mask-wearing in public

areas. Mask-wearing behaviour was largely a

response to legal restrictions and requirements.

Obedience, as a form of social influence, played a

role in mask adherence; individuals sought to avoid

social punishment, including fines or imprisonment.

Additionally, normative social influence emerged

as a means of curbing the spread of COVID-19. A positive correlation was observed between social

norms regarding mask-wearing and mask uptake,

such that individuals were more likely to wear a mask

if their friends and relatives did so.11 Furthermore,

individuals’ beliefs about engaging in the right

behaviour were associated with their behavioural

intentions. Personal norms regarding mask-wearing

were significantly associated with mask-wearing

intention.12 In the post–COVID-19 era, individuals

may continue mask-wearing even after governments

have lifted mandatory requirements, potentially

due to self-motivation for health protection. This

study aimed to identify predictors of mask-wearing

intentions and practices after the mandatory mask-wearing

requirement had been lifted in Hong Kong by

integrating the protection motivation theory (PMT)

with the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). This

integration provides a comprehensive framework for

evaluating mask-wearing intentions by examining

key factors influencing health behaviours, including

perceived severity, perceived vulnerability, attitudes,

and subjective norms. This approach may offer

a nuanced understanding of predictors of mask-wearing

intentions after the mandatory mask-wearing

requirement had been lifted.

Protection motivation theory

Protection motivation theory has been widely

used as a framework for predicting the adoption of

health-protective behaviours.13 This theory assumes

that the adoption of protective behaviour against

health threats depends on personal motivation for

self-protection. Rooted in expectancy-value theory,

PMT explains the social and cognitive processes

underlying protective behaviours. The theory is

based on the premise that the decision to counteract

a health threat is determined by threat and coping

appraisal processes.14 According to PMT, two

primary processes—threat appraisal and coping

appraisal—determine behavioural intention. Threat

appraisal consists of three components: perceived

vulnerability, perceived severity, and the perceived

reward of maladaptive behaviours. Perceived

vulnerability refers to an individual’s assessment

of the likelihood of experiencing a health threat or

developing a health condition. Perceived severity

concerns the perceived seriousness of potential

consequences associated with the condition.

Therefore, perceptions of COVID-19 severity and

vulnerability to disease would significantly predict

adherence to protective measures.15 Perceived reward

of maladaptive behaviours refers to beliefs regarding

the benefits associated with engaging in risky

behaviours. Patients with COVID-19 may experience

long COVID symptoms, including increased fatigue,

depressive symptoms, and reduced mental acuity.16

In this context, individuals may continue wearing

masks due to concerns about long-COVID severity. Thus, perceived vulnerability and perceived severity

are expected to be positively associated with the

intention to continue wearing a mask in the post–COVID-19 era, whereas the perceived reward of

maladaptive behaviours is expected to be negatively

associated with this behaviour. Three hypotheses

were proposed in relation to these elements (H1 to

H3 in the online supplementary Table).

Coping appraisal comprises perceived response

efficacy, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived

response cost. Perceived response efficacy refers

to belief in the effectiveness of the recommended

behaviour with respect to mitigating or preventing

potential harm.17 Perceived self-efficacy denotes

an individual’s confidence in overcoming barriers

to implementing the recommended behaviour.18

Perceived response cost refers to perceived costs

associated with the behaviour. Perceived response

efficacy has been positively associated with social

distancing behaviours, a non-pharmaceutical

intervention for COVID-19, among Hong Kong

adults.19 Three hypotheses were derived in relation to these elements (H4 to H6 in the online supplementary Table).

Theory of planned behaviour

The TPB is a well-established model for explaining

health-related behavioural intentions, which

are influenced by subjective norms (perceived

expectations from significant others regarding

the behaviour), attitude (personal feelings and

beliefs about the behaviour), and perceived

behavioural control (perceived ability to perform

the behaviour). Individuals with a more positive

attitude towards non-pharmaceutical interventions

exhibit a greater intention to implement such

interventions.20 Similarly, subjective norms and

perceived behavioural control have demonstrated

positive associations with the intention to adopt

interventions against COVID-19.20 Five hypotheses

were formulated in relation to these elements (H7 to

H11 in the online supplementary Table).

Integration of protection motivation theory

and theory of planned behaviour

The integration of PMT and TPB has been utilised

to predict behavioural intention in various

research contexts, such as adherence to COVID-19

behavioural guidelines,21 behavioural intention

towards COVID-19 booster vaccination,22 and

factors affecting preventive behaviours during

the COVID-19 pandemic.23 In this study, the

attitude component of TPB was used to assess an

individual’s attitude towards continuing to wear a

mask. Attitudes may be influenced by an individual’s

protection motivation. A meta-analysis identified

perceived importance, perceived benefits, perceived

effectiveness, and perceived barriers to preventive behaviour as key attitudinal factors influencing

such behaviour.24 Therefore, a conceptual model

was developed to illustrate relationships between

the constructs of PMT and TPB in predicting

continued mask-wearing after the announcement

that all mandatory mask-wearing requirements had

been lifted. Fourteen hypotheses were formulated in

relation to these elements (H12 to H25 in the online supplementary Table).

Methods

Participant recruitment

This cross-sectional study was conducted using

an online questionnaire between 8 and 20 March

2023. Participants were recruited through a non-probability

snowball sampling method that had been

used in a previous study.3 The target sample size was

determined based on the requirement that it should

be 10 times the maximum number of measurement

items associated with a single construct in the partial

least squares path model.25 In this study, 37 items

measured ten constructs, resulting in a target sample

size of 370 (10 × 37). The online questionnaire was

distributed via email and WhatsApp, a widely

used social media platform in Hong Kong. Using

the researchers’ personal social networks, eligible

individuals of various ages and educational

backgrounds were invited to participate. They were

also encouraged to share the questionnaire link with

suitable colleagues and friends. Additionally, the

researchers contacted the heads of local community

colleges to seek collaboration and support. Upon

receiving approval from directors or presidents, the

researchers sent the online questionnaire to those

leaders for recruitment of eligible participants.

Individuals were included in this study if they

were Hong Kong residents aged ≥18 years and

had access to the internet via a smartphone or

computer. Participants read a statement on the

survey’s background, anonymity, and participation

agreement before providing consent. To prevent

duplicate submissions, the prefix and first three

digits of the Hong Kong Identity Card were collected

and later removed prior to data analysis.

Measures within the questionnaire

The questionnaire, consisting of four sections,

was designed to assess perceived vulnerability,

perceived severity, perceived reward of maladaptive

behaviours, perceived response efficacy, perceived

self-efficacy, perceived response cost, attitude,

perceived behavioural control, subjective norms,

and intention to continue wearing a mask after the

mandatory mask-wearing requirement had been

lifted. The first section included two questions

focused on mask-wearing frequency after the

mandatory requirement had been lifted and on verification of Hong Kong residency. The second

section examined respondents’ adoption of health-protective

behaviours, based on PMT.26 27 The third

section measured variables related to respondents’

intention to continue wearing a mask, based on

TPB.3 27 All items in the second and third sections

were assessed using a five-point Likert scale

(1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). The final

section collected demographic information, such as

age, gender, education level, economic status, and

self-reported health status, through close-ended

questions.

Data analysis

Partial least squares structural equation modelling

was utilised to examine the conceptual framework

in this study. The SmartPLS 3.0 statistical software

(SmartPLS GmbH, Bönningstedt, Germany) was

used to assess both the reflective measurement

model and the structural model. Study reliability

and validity were evaluated by assessing internal

consistency and convergent validity in the reflective

measurement model.25 Convergent validity was

considered acceptable if the outer loadings of the

measurement items exceeded 0.5 and the average

variance extracted for each construct was >0.5.25 28

Internal reliability was evaluated using composite

reliability, which was recommended to exceed 0.708,

and Cronbach’s alpha, which should be >0.6.25 Path

coefficients were assessed within the structural

model. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

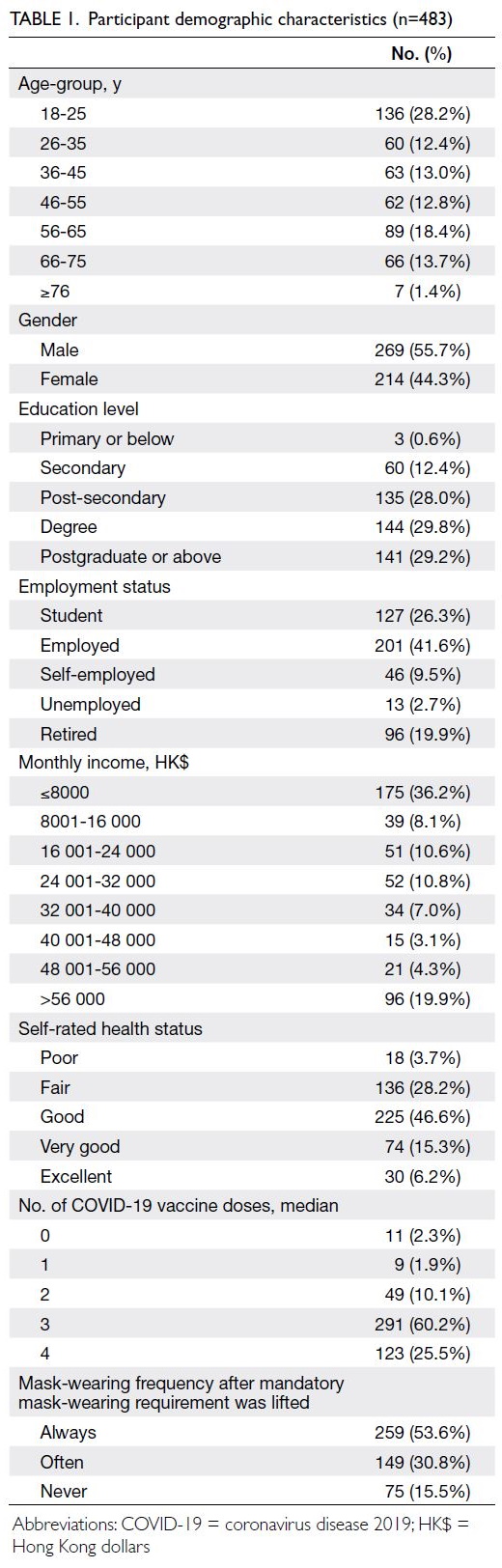

Participant characteristics

In total, 483 valid responses were included in the

data analysis. Table 1 presents the participants’

demographic characteristics. The largest proportion

of respondents belonged to the 18-25 age-group

(28.2%), followed by the 56-65 (18.4%), the 66-75

(13.7%), and the 36-45 (13.0%) age-groups. The

mean age was 43.56 years. Among the participants,

269 (55.7%) were men and 214 (44.3%) were

women. Most respondents (59.0%) had attained a

degree-level education or higher; more than two-fifths

of respondents were employed. Additionally,

approximately half of the respondents (46.6%) rated

their health status as good. More than half of the

respondents (53.6%) reported always wearing a mask

after the mandatory mask-wearing requirement

had been lifted. The median number of COVID-19

vaccine doses received was three (interquartile

range=1).

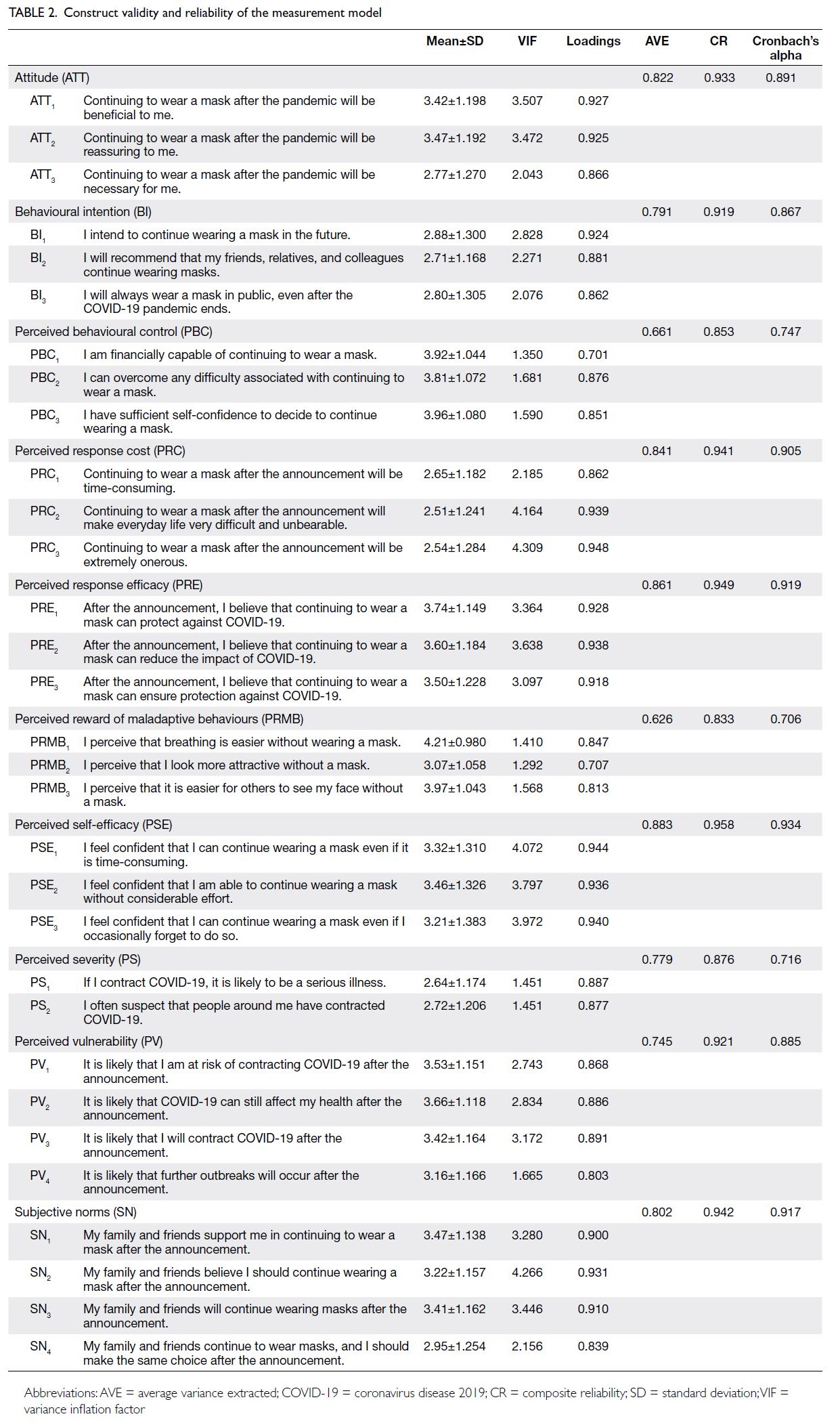

Measurement model

Table 2 presents the model reliability. Loadings >0.7

indicate a satisfactory level of item reliability.25 29 The

outer loadings of all items exceeded 0.7, except for one item related to perceived behavioural control;

consequently, this item was removed. Internal

consistency reliability was considered satisfactory

because composite reliability and Cronbach’s

alpha exceeded the threshold value of 0.7. The

average variance extracted for all constructs was

>0.5, suggesting good convergent validity after the

removal of five items: one item each from perceived

severity, perceived response efficacy, perceived

self-efficacy, attitude, and behavioural intention.

The variance inflation factor for each item was <5,

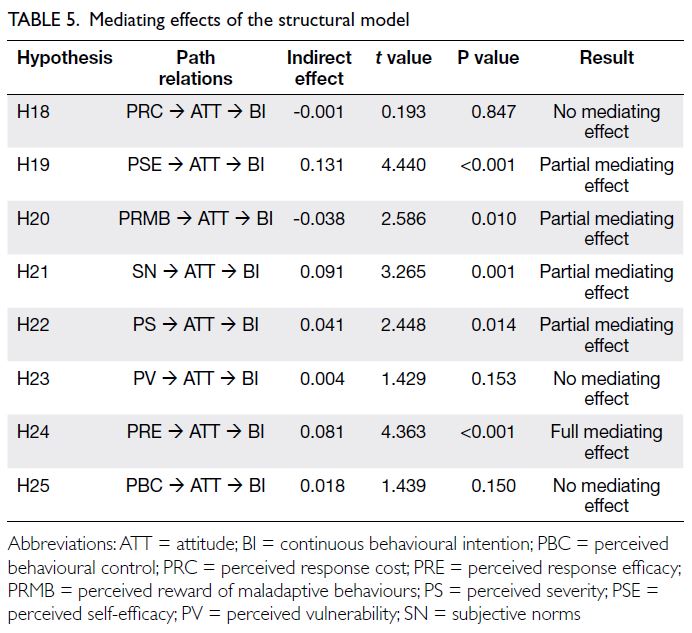

indicating no critical levels of collinearity. Table 3

depicts the results of the assessment of discriminant validity. Given the adequacy of indicator reliability,

internal consistency reliability, convergent validity,

and discriminant validity, evaluation of the structural

model could proceed.29

Table 3. Values of construct correlations, square roots of average variance extracted (italic font), and heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (grey shades)

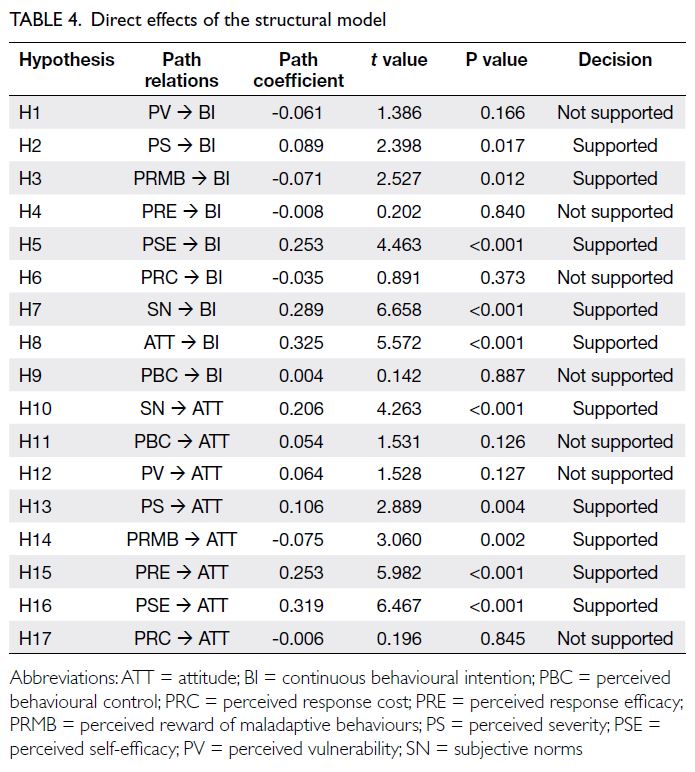

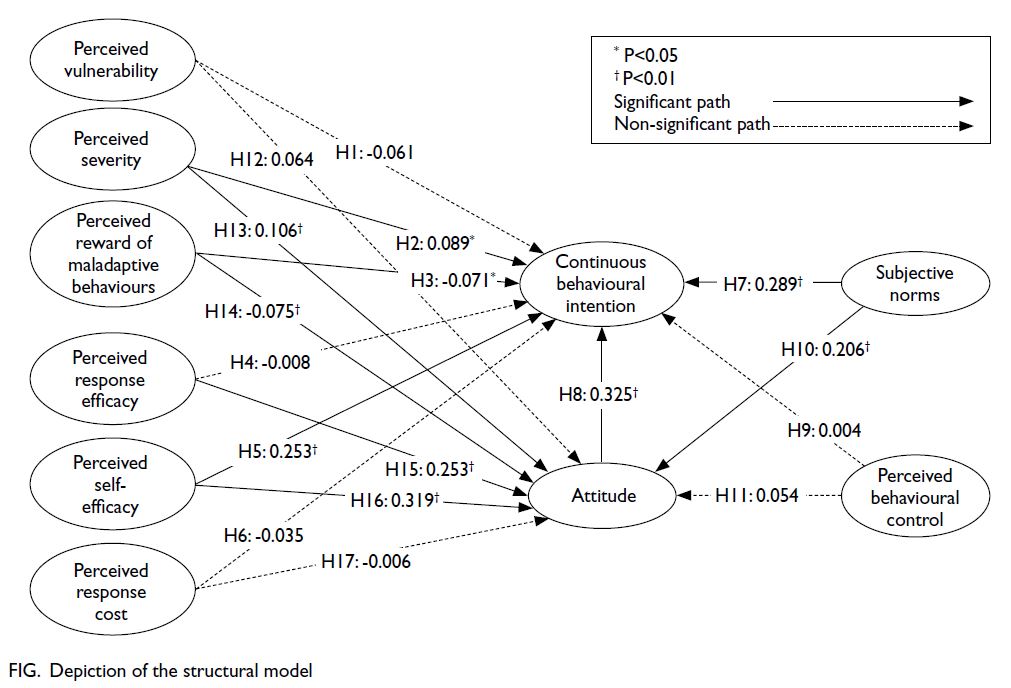

Structural model

Table 4 displays the results of direct effects in the

structural model. Of the 17 hypotheses, 10 were

supported based on the results generated through

a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples.

Four constructs—perceived severity, perceived

self-efficacy, subjective norms, and attitude—had

significant positive effects on the intention to continue wearing a mask. In contrast, perceived

reward of maladaptive behaviours had a significant

negative effect on mask-wearing intention.

Consequently, hypotheses H2, H3, H5, H7, and H8

were supported. However, perceived vulnerability,

perceived response efficacy, perceived response

cost, and perceived behavioural control were

not significantly associated with the intention to

continue wearing a mask. Thus, hypotheses H1, H4,

H6, and H9 were not supported.

Furthermore, subjective norms, perceived

severity, perceived response efficacy, and perceived

self-efficacy had significant positive effects on

attitude, whereas perceived reward of maladaptive

behaviours had a significant negative effect on

attitude. Therefore, hypotheses H10, H13, H14, H15,

and H16 were supported. However, no significant

relationships were observed between perceived

behavioural control and attitude, perceived

vulnerability and attitude, or perceived response

cost and attitude. These findings did not support

hypotheses H11, H12, and H17 (Table 4). The results

of the structural model are depicted in the Figure.

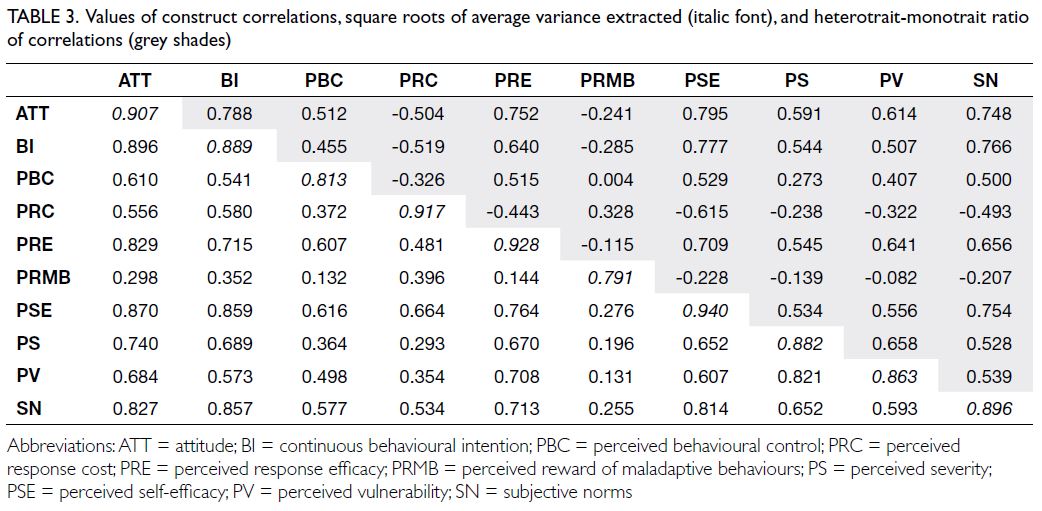

Table 5 shows the results of the mediation

model. Attitude had a partial mediating effect on

the relationships of perceived self-efficacy, perceived

reward of maladaptive behaviours, subjective

norms, and perceived severity with the intention to continue wearing a mask. These results partially

supported hypotheses H19, H20, H21, and H22.

Additionally, attitude had a full mediating effect on

the relationship between perceived response efficacy

and the intention to continue wearing a mask,

supporting hypothesis H24. However, no mediating

effect of attitude was observed in the relationships

of perceived response cost, perceived vulnerability,

and perceived behavioural control with continuous

behavioural intention. These results did not support

hypotheses H18, H23, and H25.

Discussion

Most respondents continued wearing masks during

the 3 weeks after the mandatory mask-wearing

requirement had been lifted. Perceived severity,

perceived self-efficacy, subjective norms, and

attitude were positively associated with the intention

to continue wearing a mask, whereas the perceived

reward of maladaptive behaviours was negatively

associated with this intention. Perceived severity

suggests that individuals were concerned about the

consequences of contracting COVID-19. Given that

COVID-19 had influenced daily life and behaviour

for 3 years, it is understandable that perceived

severity remained a motivator for continued mask-wearing

as a protective measure. Furthermore, some

individuals may have experienced anxiety and sought

to minimise the risk of infection. Thus, the pandemic

itself may have outweighed their desire to return to

pre-pandemic norms.30 Additionally, perceived self-efficacy

indicates that individuals with confidence in their ability to wear a mask effectively were more

likely to continue doing so. Personal protective

measures can reduce the risk of infectious diseases31;

mask-wearing is considered a feasible and acceptable

method for preventing and reducing the spread of

influenza-like illnesses.32 During the COVID-19

pandemic, some studies showed that perceived

severity and perceived self-efficacy were significantly

associated with intentions to comply with COVID-19

preventive behaviours.17 33 34 Individuals perceived

that contracting COVID-19 posed a serious threat,

whereas mask-wearing remained a feasible and

effective strategy for preventing transmission, even

after the mandatory mask-wearing requirement had

been lifted.

Notably, the perceived reward of maladaptive

behaviours had a significant negative effect on the

intention to continue wearing a mask. This finding

suggests that individuals who perceived benefits

from not wearing a mask were less likely to express

an intention to continue mask-wearing. The decision

not to wear a mask may be attributed to various

factors, including concerns about social judgement,

the inconveniences associated with preventive

measures, and daily hassles.35 36 The prolonged

COVID-19 pandemic led to pandemic fatigue, which

may have contributed to a perception among some

individuals that the pandemic had ended once the

mandatory mask-wearing requirement was lifted,

thereby reducing their motivation to continue

wearing a mask.

Attitudes and subjective norms had significant

positive effects on the intention to continue wearing

a mask. This observation indicates that individuals

who held a favourable attitude towards mask-wearing

and perceived social pressure or influence

from others to wear a mask were more likely to

express an intention to continue this practice.

Attitudes and subjective norms were previously

identified as predictors of mask-wearing intention

during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Before the

pandemic, the local population in Hong Kong

exhibited a positive attitude towards mask-wearing.

For example, patients and caregivers in outpatient

settings generally wore face masks; protecting

others was a primary motivation for this approach.37

Individuals with a positive attitude towards mask-wearing

may have been influenced by government-led

promotion of preventive behaviours since the

severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in 2003,

which caused mask-wearing to become a social

norm within the community.38 The present findings

indicate that higher levels of perceived self-efficacy,

perceived reward of maladaptive behaviours,

subjective norms, and perceived severity not only

directly increased the intention to wear a mask but

also influenced individuals’ attitudes, leading to

an increased intention to continue mask-wearing. These results provide empirical evidence supporting

the role of attitude as a mediator in the intention to

continue wearing a mask. Thus, the relationships

among perceived self-efficacy, perceived reward of

maladaptive behaviours, subjective norms, perceived

severity, and the intention to continue mask-wearing

can also be explained by individuals’ attitudes.

In the present study, perceived vulnerability did

not directly predict the intention to continue wearing

a mask. A study also showed no significant association

between perceived vulnerability and the adoption

of preventive behaviours.39 A possible explanation

is that the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic led

individuals to consider themselves less vulnerable

compared with early stages of the pandemic. The

removal of government restrictions may have further

reinforced the perception of reduced vulnerability to

COVID-19.40 Additionally, the results of this study

did not demonstrate a statistically significant direct

effect between perceived response efficacy and the

intention to continue wearing a mask. However,

a mediating role for attitude was identified in this

relationship, indicating that perceived response

efficacy influenced attitude, which then determined

the intention to wear a mask.

Implications

This study highlights the importance of understanding

the predictors of mask-wearing intention after the

mandatory mask-wearing requirement was lifted.

A high frequency of mask-wearing was observed

after the removal of the requirement. This finding

has implications for future research regarding the

long-term effects of habitual mask use and its impact

on public health. From a practical perspective, the

findings indicate that attitude towards continued

mask-wearing was the strongest predictor of mask-wearing

intention, suggesting that citizens are

prepared for future health crises. Policymakers

can utilise these insights to develop guidelines

encouraging mask use during influenza seasons.

Limitations

This study had certain limitations. First, the

sampling method relied on non-probability snowball

sampling, which may affect the representativeness

of the sample. Second, participation was limited to

individuals with access to email and social media,

leading to overrepresentation of younger and more

educated individuals. Younger participants may

consider themselves less likely to experience severe

health consequences if they contract COVID-19.

Consequently, the findings may not be generalisable

to the entire population.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to use an online questionnaire to identify the

predictors of mask-wearing intention after the

mandatory mask-wearing requirement in Hong

Kong was lifted in March 2023. Attitude towards

continued mask-wearing, subjective norms, and

perceived self-efficacy exhibited strong positive

effects on the intention to continue wearing a

mask. Regarding research implications, this study

provides new insights into the evaluation of Hong

Kong citizens’ transition to a post-pandemic era.

The high frequency of mask-wearing observed may

be attributed to concerns about COVID-19 and

the establishment of mask-wearing as an accepted

and habitual behaviour within the local population.

Furthermore, the findings suggest that Hong Kong

citizens are well prepared for future health crises,

such as severe acute respiratory syndrome and

additional COVID-19 outbreaks. The positive

attitude towards mask-wearing reflects recognition

of its feasibility and effectiveness as a durable non-pharmaceutical

public health intervention to reduce

airborne disease transmission.

Author contributions

Concept or design: TKC Ng, BYF Fong.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: TKC Ng, BYF Fong.

Drafting of the manuscript: TKC Ng, BYF Fong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: TKC Ng, BYF Fong.

Drafting of the manuscript: TKC Ng, BYF Fong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Research Committee

of the College of Professional and Continuing Education of

Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong (Ref No.:

RC/ETH/H/133). Informed consent was obtained from all

participants prior to the study and for the publication of this

research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 Dashboard.

Available from: https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 13 Mar 2025.

2. Lison A, Banholzer N, Sharma M, et al. Effectiveness

assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions: lessons

learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Public

Health 2023;8:e311-7. Crossref

3. Duan Y, Shang B, Liang W, et al. Predicting hand washing,

mask wearing and social distancing behaviors among older

adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrated

social cognition model. BMC Geriatr 2022;22:91. Crossref

4. Diallo I, Ndejjo R, Leye MM, et al. Unintended consequences

of implementing non-pharmaceutical interventions for the

COVID-19 response in Africa: experiences from DRC,

Nigeria, Senegal, and Uganda. Global Health 2023;19:36. Crossref

5. ÓhAiseadha C, Quinn GA, Connolly R, et al. Unintended

consequences of COVID-19 non-pharmaceutical

interventions (NPIs) for population health and health

inequalities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023;20:5223. Crossref

6. Limb M. COVID-19: scientists and medics warn that

it is too soon to lift all restrictions in England. BMJ

2022;376:o469. Crossref

7. Zhan Z, Li J, Cheng ZJ. Zero-COVID strategy: what’s next?

Int J Health Policy Manag 2023;12:6757. Crossref

8. Dunstan J. Victoria to ease COVID-19 mask mandate

on public transport from 11:59pm Thursday. ABC News

[newspaper on the Internet]. 2022 Sep 21. Available from:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-09-21/victoria-mask-mandate-ends-trains-trams-buses-transport/101460606. Accessed 7 Jul 2024.

9. Lin C. Singapore relaxes COVID travel curbs, mask rules

further. Reuters [newspaper on the Internet]. 2023 Feb

9. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/singapore-relaxes-covid-travel-curbs-mask-rules-further-2023-02-09/. Accessed 7 Jul 2024.

10. Hong Kong SAR Government. Government lifts all

mandatory mask-wearing requirements [press release].

2023 Feb 28. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202302/28/P2023022800677.htm. Accessed 13 Mar 2025.

11. Barceló J, Sheen GC. Voluntary adoption of social welfare-enhancing

behavior: mask-wearing in Spain during the

COVID-19 outbreak. PloS One 2020;15:e0242764. Crossref

12. Lipsey NP, Losee JE. Social influences on mask-wearing

intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Pers

Psychol Compass 2023;17:e12817. Crossref

13. Ezati Rad R, Mohseni S, Kamalzadeh Takhti H, et al.

Application of the protection motivation theory for

predicting COVID-19 preventive behaviors in Hormozgan,

Iran: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health

2021;21:466. Crossref

14. Fischer-Preßler D, Bonaretti D, Fischbach K. A protection-motivation

perspective to explain intention to use and

continue to use mobile warning systems. Bus Inf Syst Eng

2022;64:167-82. Crossref

15. González-Castro JL, Ubillos-Landa S, Puente-Martínez A,

Gracia-Leiva M. Perceived vulnerability and severity predict adherence to COVID-19 protection measures:

the mediating role of instrumental coping. Front Psychol

2021;12:674032. Crossref

16. Bierbauer W, Lüscher J, Scholz U. Illness perceptions in

long-COVID: a cross-sectional analysis in adults. Cogent

Psychol 2022;9:2105007. Crossref

17. Lahiri A, Jha SS, Chakraborty A, Dobe M, Dey A. Role

of threat and coping appraisal in protection motivation

for adoption of preventive behavior during COVID-19

pandemic. Front Public Health 2021;9:678566. Crossref

18. Bandura A. The growing centrality of self-regulation in

health promotion and disease prevention. Eur Health

Psychol 2005;7:11-2.

19. Yu Y, Lau JT, Lau MM. Competing or interactive effect

between perceived response efficacy of governmental

social distancing behaviors and personal freedom on

social distancing behaviors in the Chinese adult general

population in Hong Kong. Int J Health Policy Manag

2022;11:498-507. Crossref

20. Ohnmacht T, Hüsser AP, Thao VT. Pointers to interventions

for promoting COVID-19 protective measures in tourism:

a modelling approach using domain-specific risk-taking

scale, theory of planned behaviour, and health belief model.

Front Psychol 2022;13:940090. Crossref

21. Nudelman G. Predicting adherence to COVID-19

behavioural guidelines: a comparison of protection

motivation theory and the theory of planned behaviour.

Psychol Health 2024;39:1689-705. Crossref

22. Zhou M, Liu L, Gu SY, et al. Behavioral intention and its

predictors toward COVID-19 booster vaccination among

Chinese parents: applying two behavioral theories. Int J

Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:7520. Crossref

23. Khaday S, Li KW, Dorloh H. Factors affecting preventive

behaviors for safety and health at work during the

COVID-19 pandemic among Thai construction workers.

Healthcare (Basel) 2023;11:426. Crossref

24. Liang W, Duan Y, Li F, et al. Psychosocial determinants of

hand hygiene, facemask wearing, and physical distancing

during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med 2022;56:1174-87. Crossref

25. Hair Jr JF, Hult GT, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A Primer on

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM).

Los Angeles [CA]: Sage Publications; 2021.

26. Youn SY, Lee JE, Ha-Brookshire J. Fashion consumers’

channel switching behavior during the COVID-19:

protection motivation theory in the extended planned

behavior framework. Cloth Text Res J 2021;39:139-56. Crossref

27. Zhang X, Liu S, Wang L, Zhang Y, Wang J. Mobile health

service adoption in China: integration of theory of planned

behavior, protection motivation theory and personal health

differences. Online Inf Rev 2020;44:1-23. Crossref

28. Ting MS, Goh YN, Isa SM. Determining consumer

purchase intentions toward counterfeit luxury goods in

Malaysia. Asia Pac Manage Rev 2016;21:219-30. Crossref

29. Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Hair JF. Partial least squares

structural equation modeling. In: Homburg C, Klarmann

M, Vomberg AE, editors. Handbook of Market Research.

Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021: 587-632. Crossref

30. Mo PK, Yu Y, Lau MM, Ling RH, Lau JT. Time to lift up

COVID-19 restrictions? Public support towards living

with the virus policy and associated factors among Hong

Kong general public. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023;20:2989. Crossref

31. Masai AN, Akin L. Practice of COVID-19 preventive

measures and risk of acute respiratory infections: a

longitudinal study in students from 95 countries. Int J

Infect Dis 2021;113:168-74. Crossref

32. Polonsky JA, Bhatia S, Fraser K, et al. Feasibility,

acceptability, and effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical

interventions against infectious diseases among crisis-affected

populations: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty

2022;11:14. Crossref

33. Acar D, Kıcali ÜÖ. An integrated approach to COVID-19

preventive behaviour intentions: protection motivation

theory, information acquisition, and trust. Soc Work

Public Health 2022;37:419-34. Crossref

34. Kwok KO, Li KK, Chan HH, et al. Community responses

during early phase of COVID-19 epidemic, Hong Kong.

Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26:1575-9. Crossref

35. Lai DW, Jin J, Yan E, Lee VW. Predictors and moderators of

COVID-19 pandemic fatigue in Hong Kong. J Infect Public Health 2023;16:645-50. Crossref

36. Rieger MO. To wear or not to wear? Factors influencing

wearing face masks in Germany during the COVID-19

pandemic. Asian J Soc Health Behav 2020;3:50-4. Crossref

37. Ho HS. Use of face masks in a primary care outpatient

setting in Hong Kong: knowledge, attitudes and practices.

Public Health 2012;126:1001-6. Crossref

38. Mo PK, Lau JT. Illness representation on H1N1 influenza

and preventive behaviors in the Hong Kong general

population. J Health Psychol 2015;20:1523-33. Crossref

39. Zancu SA, Măirean C, Diaconu-Gherasim LR. The

longitudinal relation between time perspective and

preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic:

the mediating role of risk perception. Curr Psychol

2024;43:12981-9. Crossref

40. Stefanczyk MM, Rokosz M, Białek M. Changes in perceived

vulnerability to disease, resilience, and disgust sensitivity

during the pandemic: a longitudinal study. Curr Psychol

2024;43:23412-24. Crossref