Chronic peritoneal dialysis in Chinese infants and children younger than two years

Hong Kong Med J 2016 Aug;22(4):365–71 | Epub 17 Jun 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154781

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Chronic peritoneal dialysis in Chinese infants and children younger than two years

YH Chan, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics);

Alison LT Ma, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics);

PC Tong, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics);

WM Lai, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics);

Niko KC Tse, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)

Paediatric Nephrology Centre, Department of Paediatric and Adolescent

Medicine, Princess Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr YH Chan (genegene.chan@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: To review the outcome for Chinese

infants and young children on chronic peritoneal

dialysis.

Methods: The Paediatric Nephrology Centre of

Princess Margaret Hospital is the designated site

offering chronic dialysis to children in Hong Kong.

Medical records of children who started chronic

peritoneal dialysis before the age of 2 years, from 1

July 1995 to 31 December 2013, were retrieved and

retrospectively reviewed.

Results: Nine Chinese patients (male-to-female ratio, 3:6)

were identified. They were commenced on automated

peritoneal dialysis at a median age of 4.7 (interquartile

range, 1.1-13.3) months. The median duration of

chronic peritoneal dialysis was 40.9 (interquartile

range, 22.9-76.2) months. The underlying aetiologies

were renal dysplasia (n=3), pneumococcal-associated

haemolytic uraemic syndrome (n=3), ischaemic

nephropathy (n=2), and primary hyperoxaluria I

(n=1). Peritonitis and exit-site infection rate was

1 episode per 46.5 patient-months and 1 episode

per 28.6 patient-months, respectively. Dialysis

adequacy (Kt/Vurea >1.8) was achieved in 87.5% of

patients. Weight gain was achieved in our patients

although three required gastrostomy. Four patients

were delayed in development. All patients survived

except one patient with primary hyperoxaluria I who

died of acute portal vein thrombosis following liver

transplantation. One patient with pneumococcal-associated

haemolytic uraemic syndrome had

sufficient renal function to be weaned off dialysis.

Four patients received deceased donor renal transplantation

after a mean waiting time of 76.7 months. Three

patients remained on chronic peritoneal dialysis at

the end of the study.

Conclusions: Chronic peritoneal dialysis is technically

difficult in infants. Nonetheless, low peritonitis rate,

low exit-site infection rate, and no chronic peritoneal

dialysis–related mortality can be achieved. Chronic

peritoneal dialysis offers a promising strategy to

bridge the way to renal transplantation.

New knowledge added by this study

- Literature on infant chronic peritoneal dialysis (CPD) is scarce. This is the first report about long-term outcome of Chinese infants on CPD.

- The local catheter-related infection rate is low compared with western countries.

- CPD in infancy is a feasible modality as a bridge to transplantation with low infection and mortality rate. A shared decision-making process between parents and paediatric nephrologists is necessary to provide an optimal care plan for this group of patients, considering the predicted outcome, associated co-morbidities, and family burden.

Introduction

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is a rare disease with

high mortality in infants and young children under 2

years of age. In the past, the decision to initiate infant

dialysis was not easy due to technical difficulties

and poor clinical outcome, as evidenced by a 1990

survey showing that only 50% of paediatric

nephrologists would offer dialysis to ESRD children

younger than 1 year, and only 40% would offer

dialysis to neonates.1 With technological advances

and improving outcome for children on dialysis in

terms of physical growth, development and quality

of life,2 3 most paediatric nephrologists will now consider peritoneal dialysis (PD) as a bridge to renal

transplantation. Data in North American Pediatric

Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS)

2011 indicated that 92% of ESRD children younger

than 2 years were on chronic PD (CPD).4

Literature in this area is scarce2 3 5 6 especially

on the long-term outcome of these infants in the

Chinese population. As the only tertiary referral

paediatric nephrology centre in Hong Kong, we

retrospectively reviewed our experience in the

epidemiology, dialysis prescription, complications,

and outcome in this group of patients.

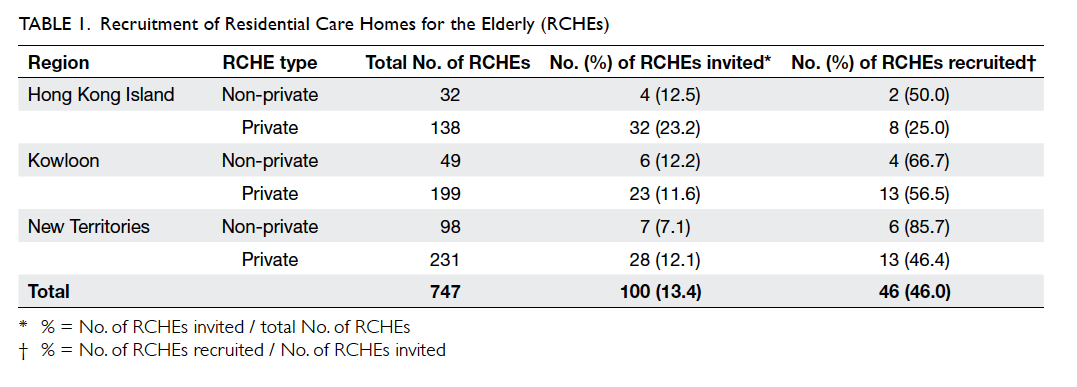

Methods

The Paediatric Nephrology Centre of Princess

Margaret Hospital is the designated site offering

renal replacement therapy to children in Hong Kong.

Medical records of children who started CPD before

2 years old, from 1 July 1995 to 31 December 2013,

were retrieved and reviewed. Information regarding

their primary renal diagnosis, co-morbidities, growth

profile, infectious and non-infectious complications,

dialysis prescription, dialysis adequacy, peritoneal

membrane transport status, relevant laboratory

investigations, and final outcome were reviewed.

Data collected were recorded on data entry forms.

Patients who underwent CPD for less than 6 months

were excluded. The study was approved by the ethics

committee of Princess Margaret Hospital.

In our centre, CPD was the preferred dialysis

modality in young children; PD was performed

by automated cycler in the modes of nocturnal

intermittent peritoneal dialysis (NIPD), continuous

cyclic peritoneal dialysis (CCPD), continuous optimal

peritoneal dialysis, and tidal peritoneal dialysis.

Peritoneal equilibration test was performed annually

with membrane transport status classified as high,

high-average, low-average, or low transporters.7 8 Dialysis adequacy was monitored by both clinical

parameters and biochemical parameters. Due to

limited information on residual renal function,

solute clearance referred to contribution by CPD

only, and was expressed in terms of Kt/Vurea.

Peritonitis was defined as cloudy peritoneal

effluent, with white cell count of >100/mm3 in the

dialysate with at least 50% polymorphonuclear

leukocytes.9 Additionally, clinical symptoms of fever

with or without abdominal pain were included. Exit-site

infection (ESI) was diagnosed in the presence

of peri-catheter swelling, redness, tenderness, and

discharge at the exit site.9 Developmental delay was

defined as children who received special education

or failed to reach a normal developmental milestone

in two or more developmental domains (eg gross

motor, cognition, etc).

Chronic kidney disease–mineral bone disease

(CKD-MBD) was defined as a systemic disorder

of mineral bone metabolism due to renal failure,

manifesting as biochemical abnormalities (calcium,

phosphate, parathyroid hormone [PTH], or vitamin

D metabolism), abnormal bone turnover, or vascular

calcification.10 Renal osteodystrophy, the skeletal component

of CKD-MBD, was defined as alteration of

bone morphology in patients with ESRD.10 Target of

PTH ranged from 11 to 33 pmol/L (100-300 pg/mL)

in children on CPD, supported by recent data from

the International Pediatric Peritoneal Dialysis

Network (IPDN).11

Statistical analysis

Data collection and analysis were performed with

Microsoft Excel 2010. The demographic data and

biochemical parameters were expressed as mean ±

standard deviation, range, median, interquartile

range (IQR), number, or percentage as appropriate.

Height and weight were expressed as standard

deviation scores (SDSs), calculated according to a

local study on growth of children.12

Results

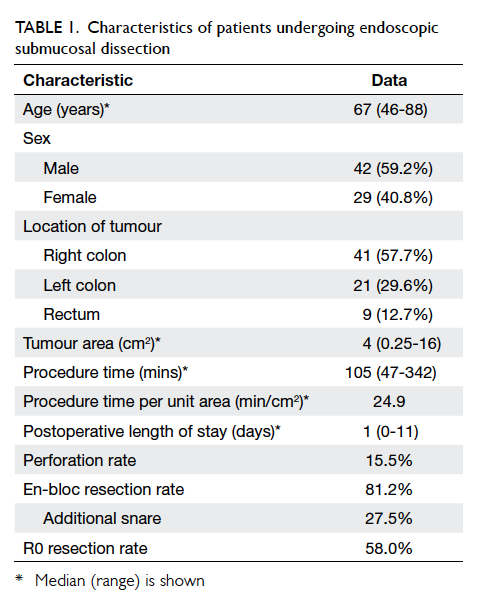

Patient characteristics

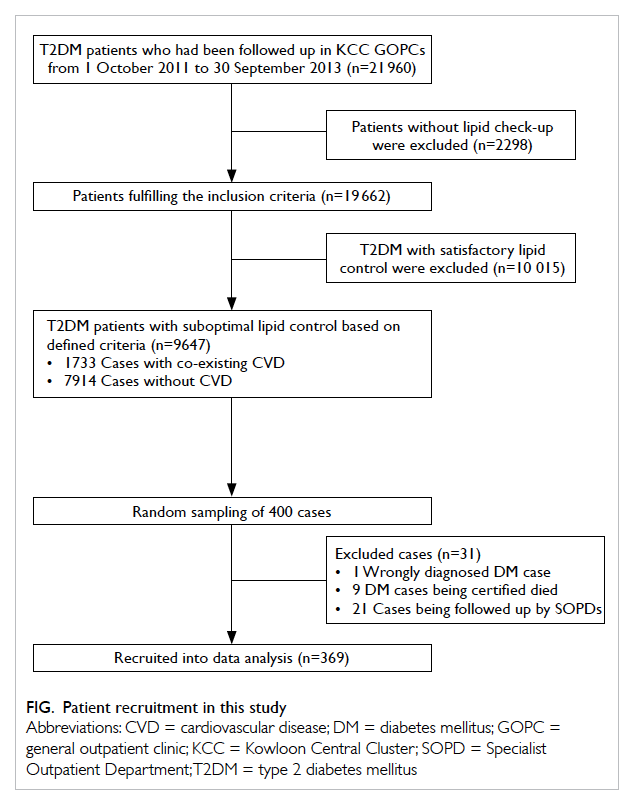

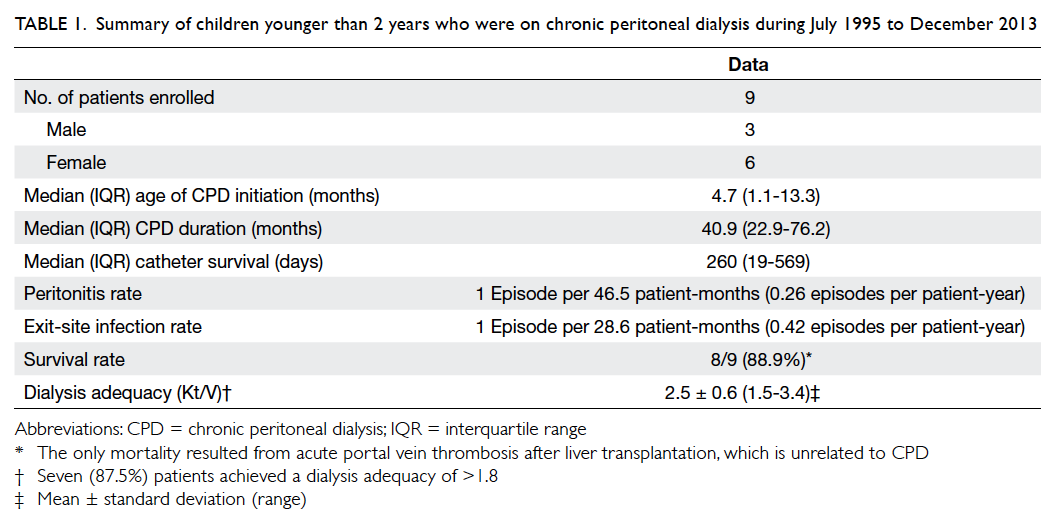

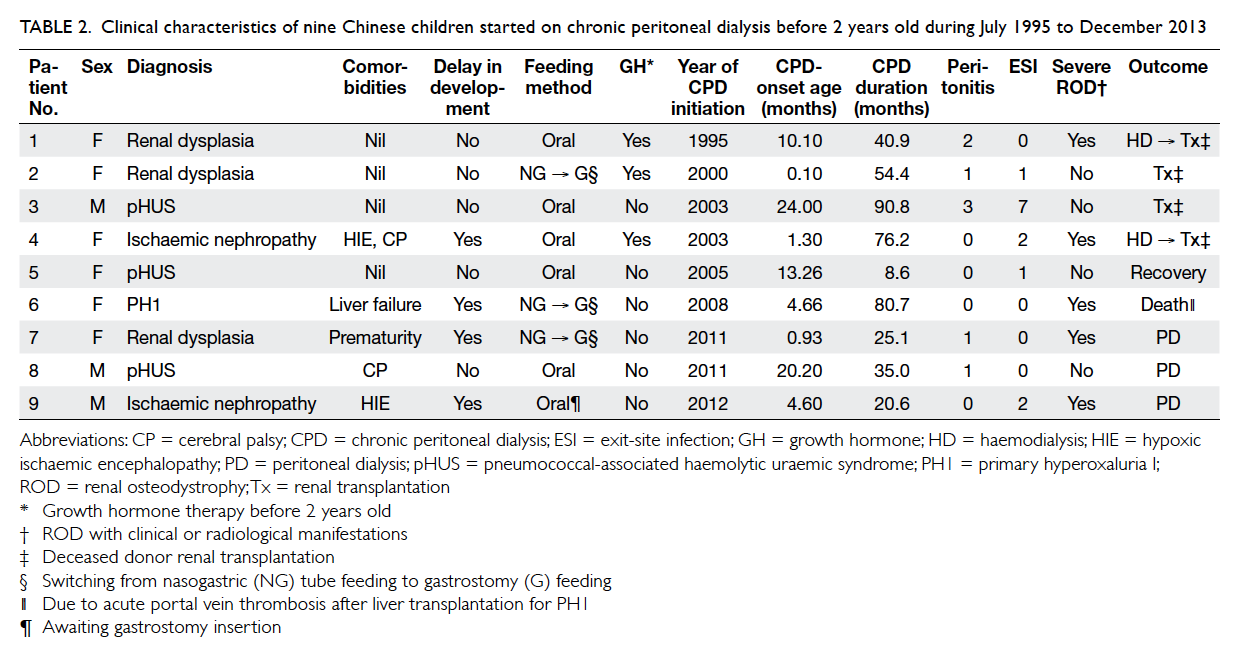

From 1995 to 2013, nine Chinese children under 2

years of age (3 boys and 6 girls) receiving CPD

were identified. The mean estimated glomerular

filtration rate immediately prior to dialysis was 6.9

± 3.8 (range, 3.9-15) mL/min/1.73 m2, calculated by

Schwartz Formula. The median age at initiating CPD

was 4.7 (IQR, 1.1-13.3) months. The median duration

of CPD was 40.9 (IQR, 22.9-76.2) months. The most

common causes of ESRD were renal dysplasia (n=3,

33%) and pneumococcal-associated haemolytic

uraemic syndrome (pHUS) [n=3, 33%], followed

by ischaemic nephropathy due to severe perinatal

asphyxia (n=2, 22%) and primary hyperoxaluria

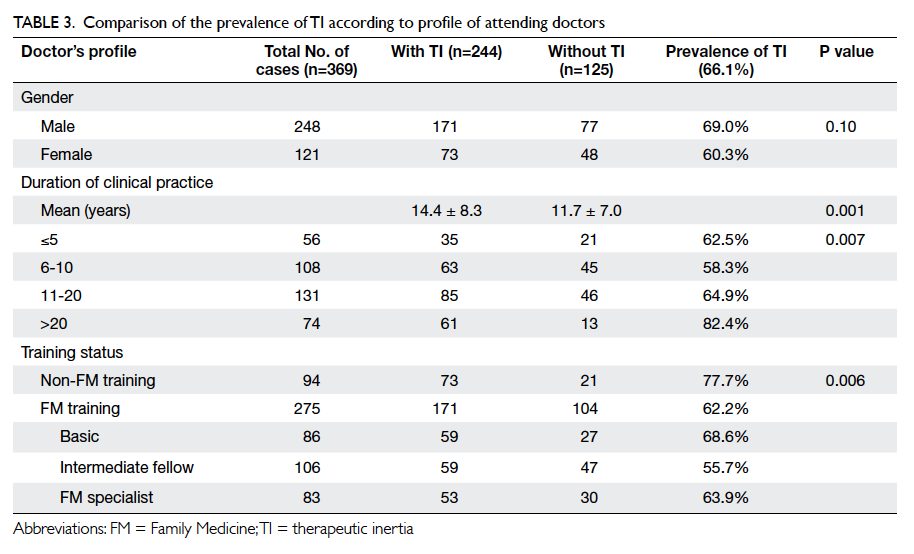

I (PH1) [n=1, 11%] (Tables 1 and 2). All three patients with pHUS presented with pneumococcal

pneumonia, microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia,

and acute kidney injury. Either direct Coombs test or

T-antigen test was positive to support the diagnosis

of pHUS.

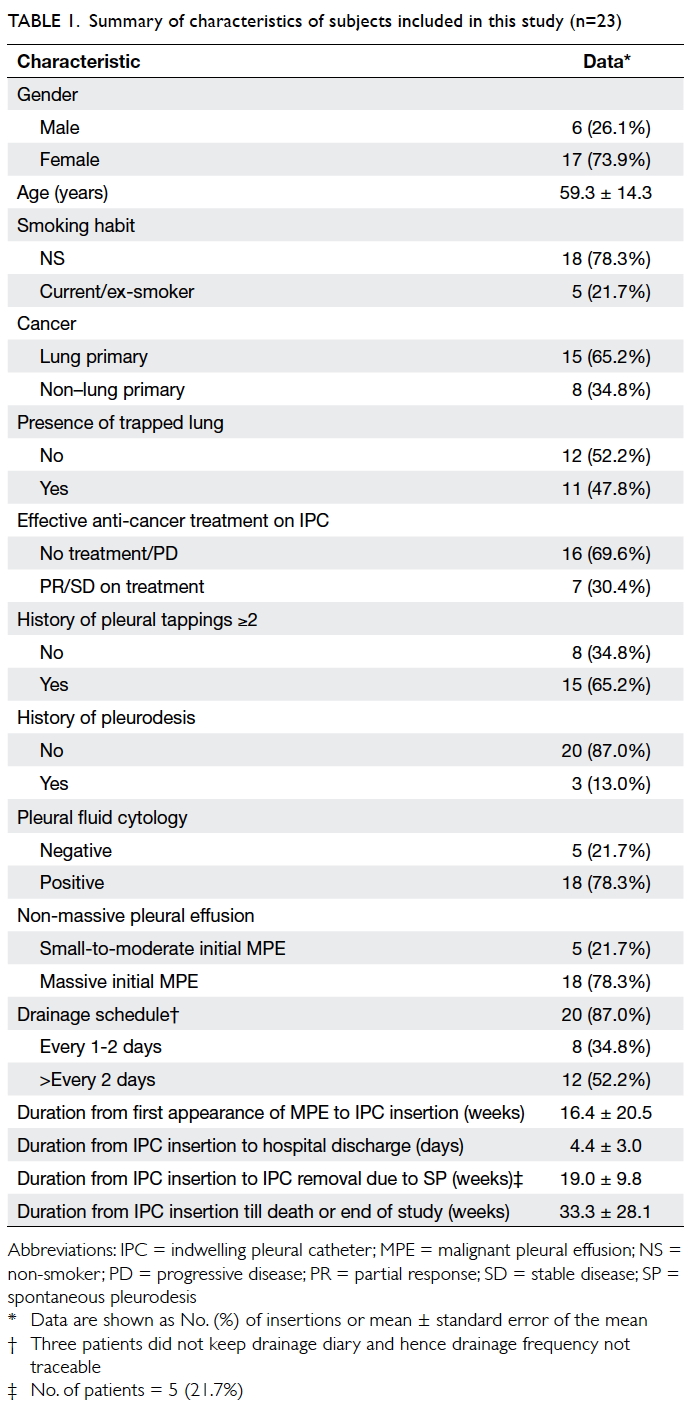

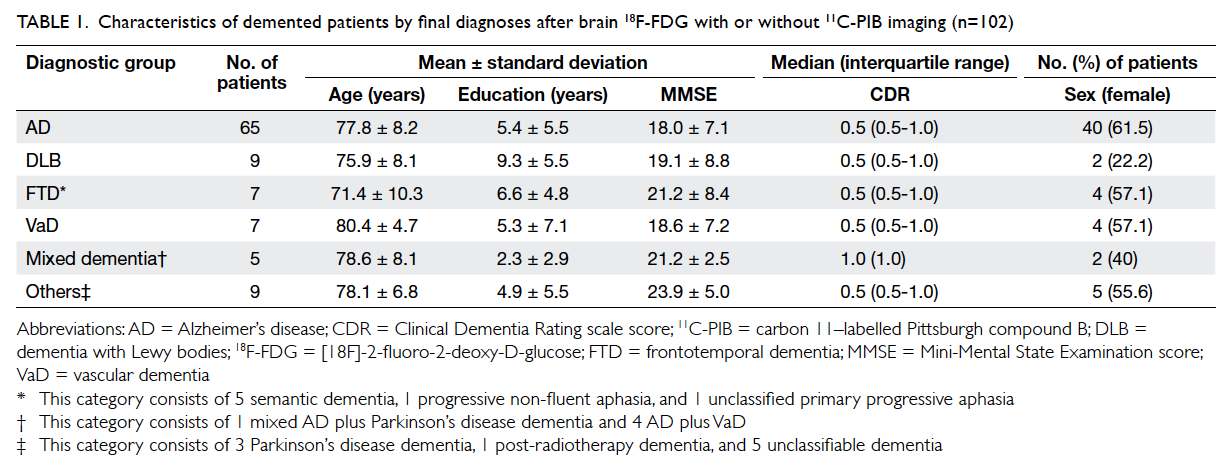

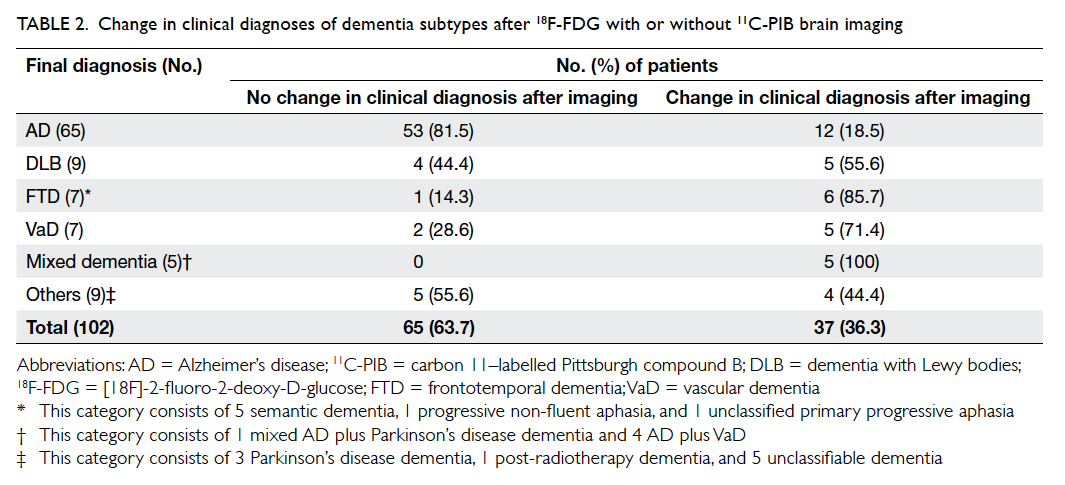

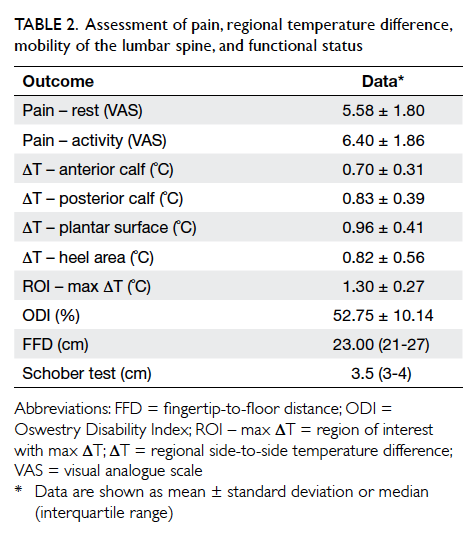

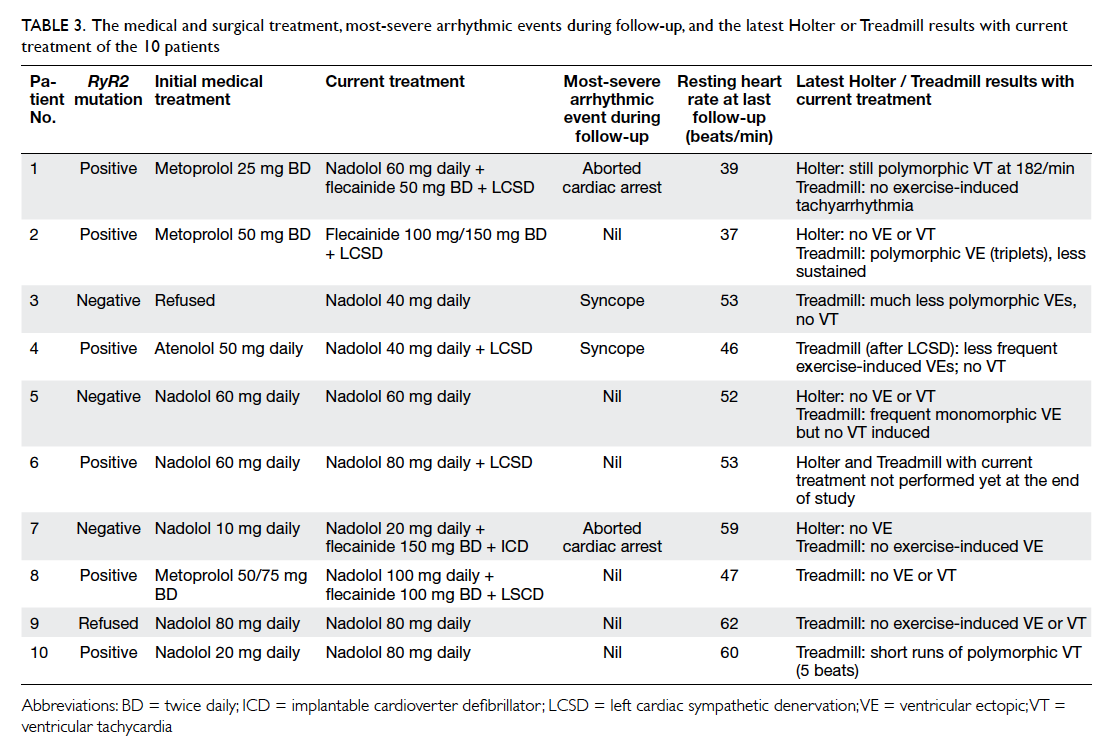

Table 1. Summary of children younger than 2 years who were on chronic peritoneal dialysis during July 1995 to December 2013

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of nine Chinese children started on chronic peritoneal dialysis before 2 years old during July 1995 to December 2013

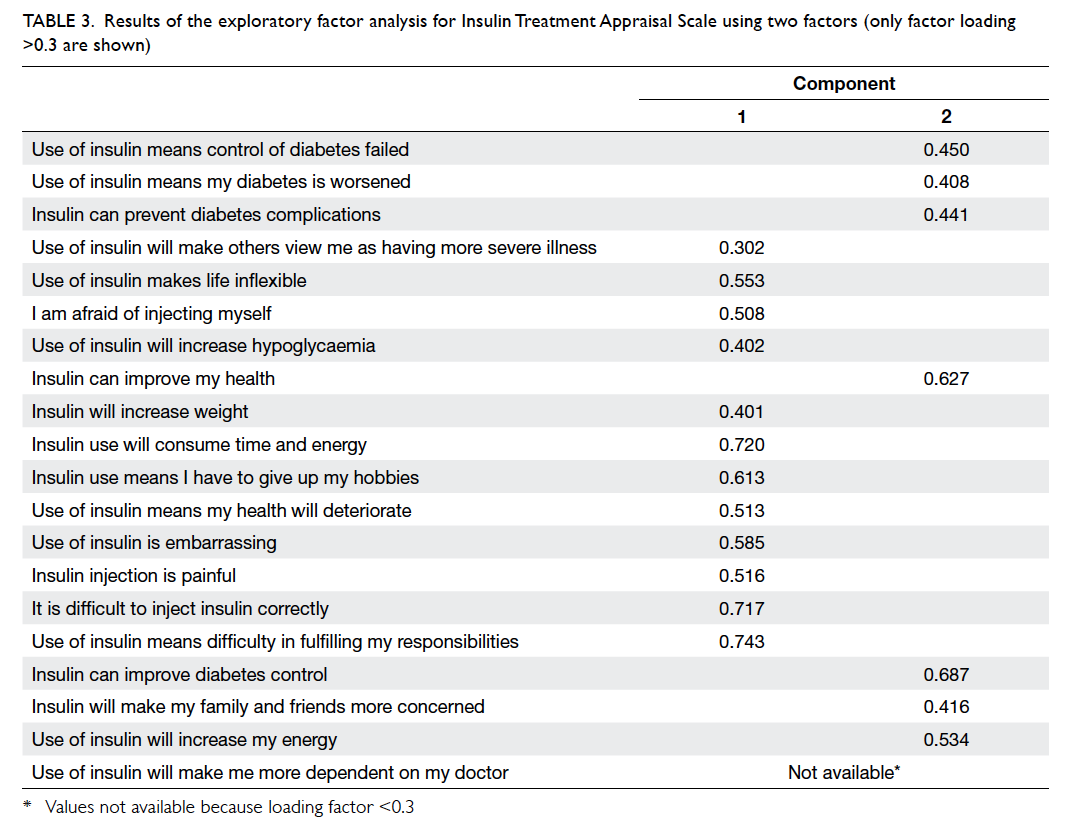

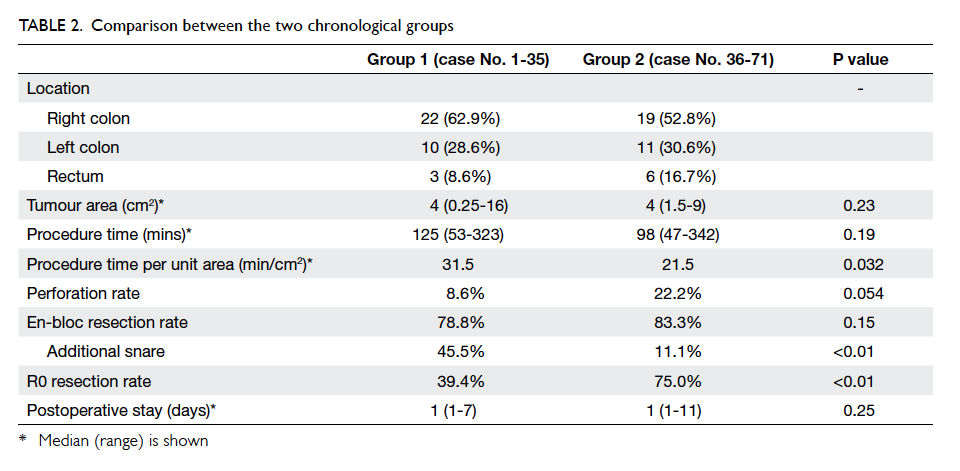

Peritoneal dialysis prescription, transporter status, and peritoneal dialysis adequacy

All patients were put on automated peritoneal

dialysis (APD). Initially, eight children were on NIPD

and only one was on CCPD. Over the course of CPD,

five (56%) patients changed to CCPD, and one (11%)

patient changed to tidal PD because of drainage pain.

Three (33%) patients remained on NIPD. Decreasing

residual renal function and inadequate dialysis were

the most common reasons for changing modes of

CPD.

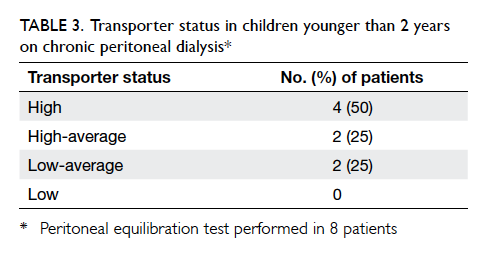

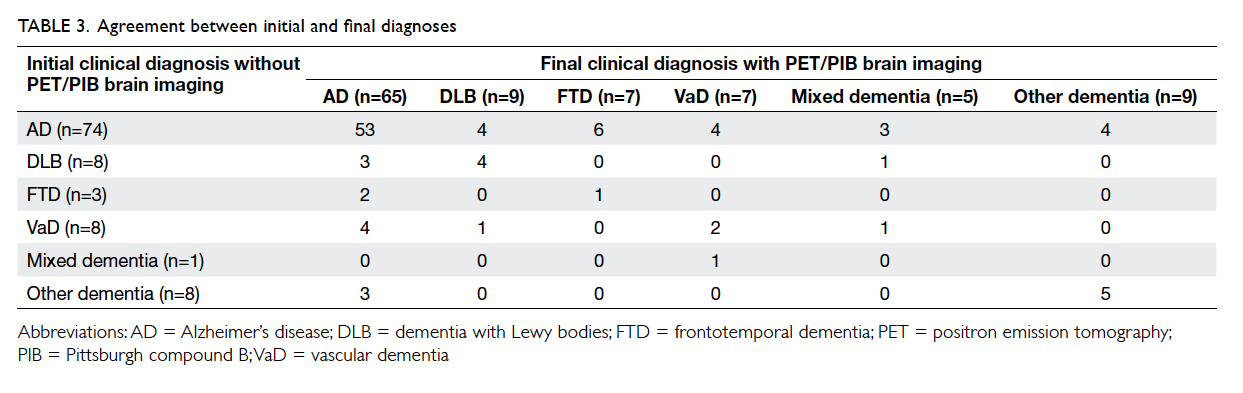

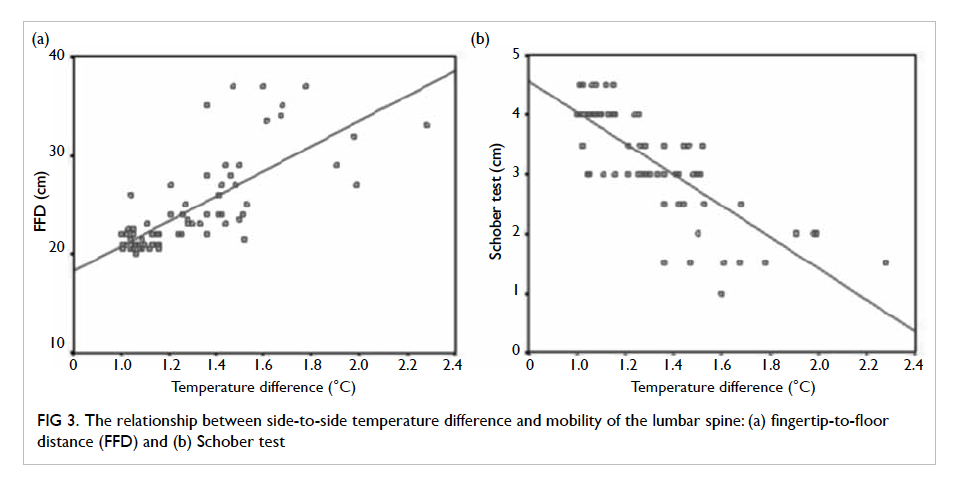

Peritoneal equilibration test and dialysis

adequacy assessment were performed in eight

patients. Four patients were high transporters, while

two patients were high-average transporters and two

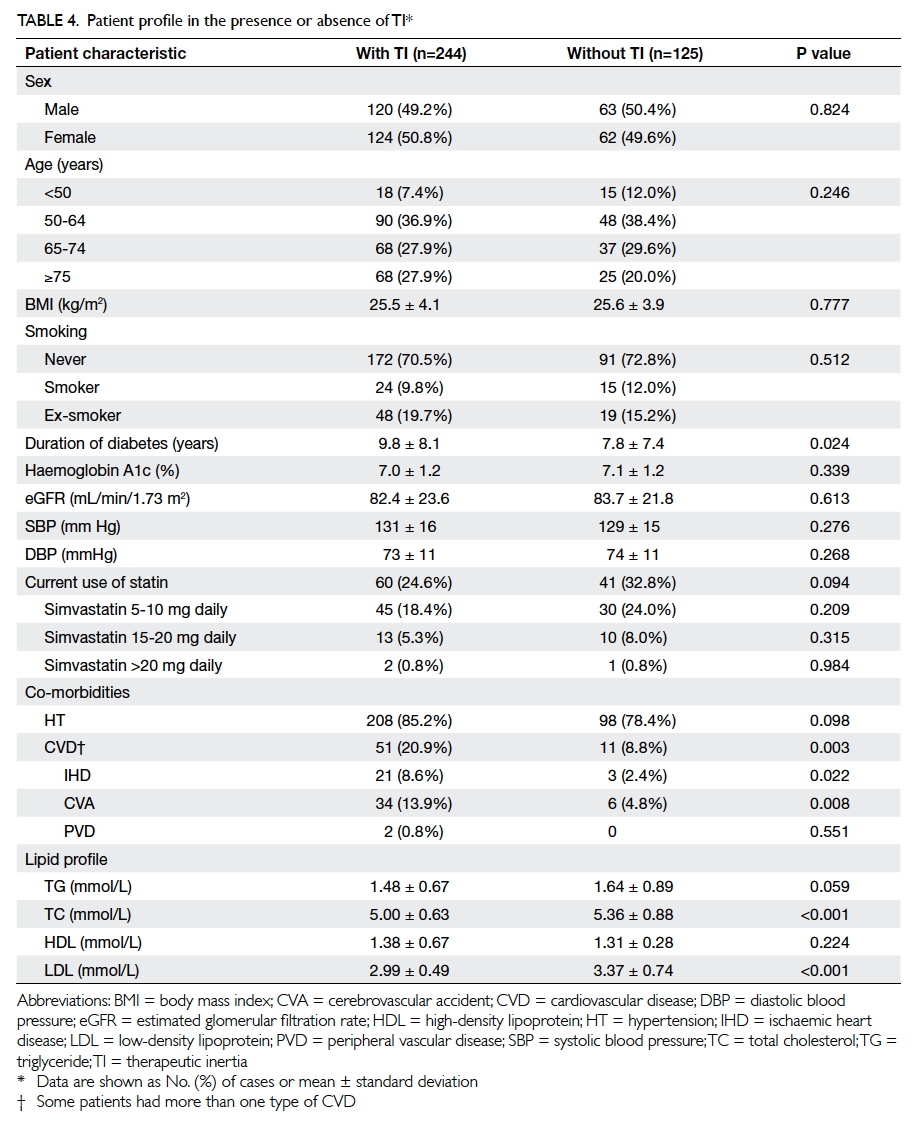

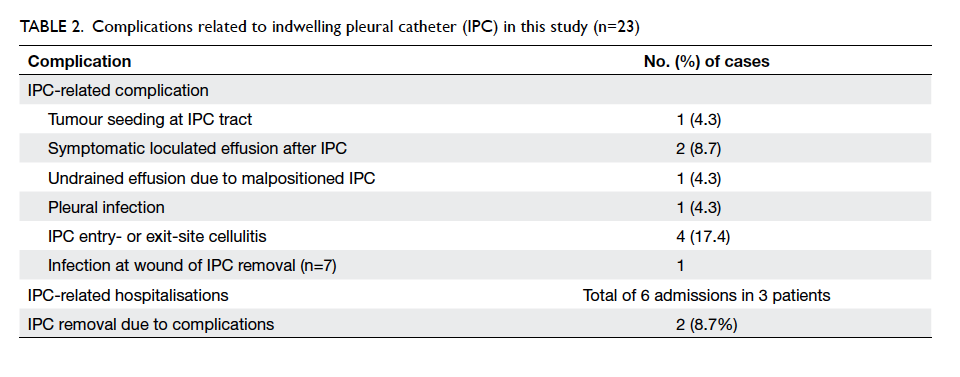

patients were low-average transporters (Table 3). Seven (87.5%) patients achieved a dialysis adequacy

(Kt/Vurea) of >1.8. The mean Kt/Vurea was 2.5 ± 0.6

(range, 1.5-3.4). The mean weekly creatinine clearance

was 38.3 ± 6.2 (range, 25.6-47.1) L/week/1.73 m2.

Catheter survival

During the study period, 23 episodes of Tenckhoff

catheter insertion were carried out in these nine

patients. The median catheter survival was 260 (IQR,

19-569) days. Only one patient did not require any

catheter change. Fourteen catheter changes were

performed in eight patients. Catheters were replaced

once in four patients, twice in three patients, and

4 times in one patient. The most common reason

for catheter change was catheter blockage due to

omental wrap (n=7, 50%), followed by chronic ESI

or refractory peritonitis (n=4, 29%), migration

or malposition (n=2, 14%), and cuff extrusion

(n=1, 7%). While omentectomy was not routinely

performed, 44% patients eventually required partial

omentectomy due to omental wrap.

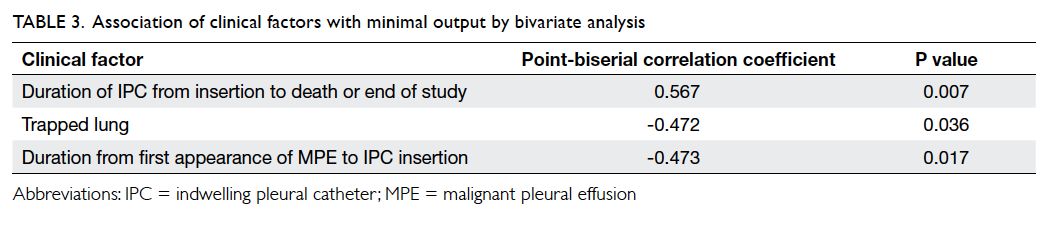

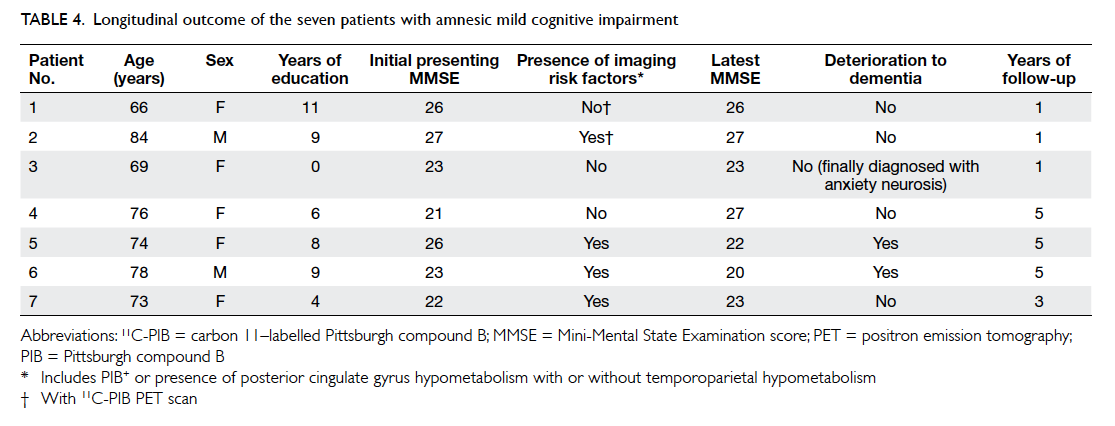

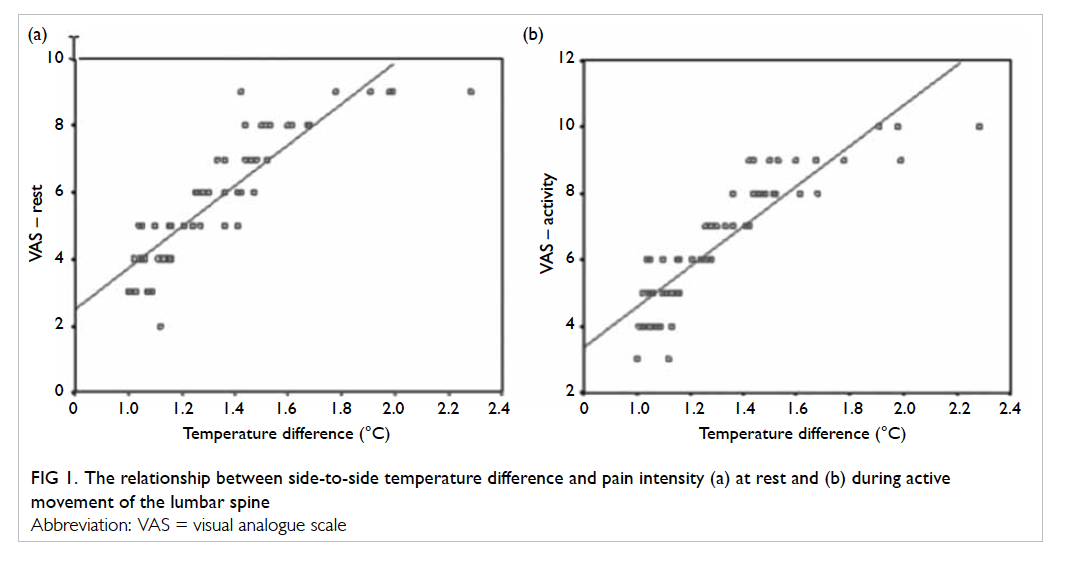

Peritonitis, exit-site infection, and surgical complications

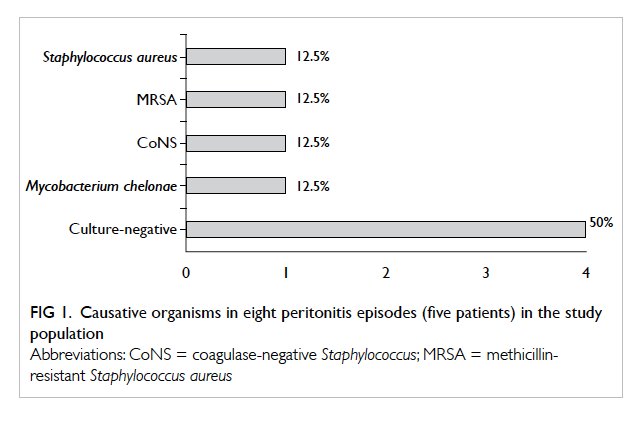

Five patients experienced a total of eight episodes

of peritonitis. Four patients did not have peritonitis.

Peritonitis rate was 0.26 episode per patient-year

or 1 episode per 46.5 patient-months. Two

(25%) episodes were caused by Staphylococcus

aureus, one of which was methicillin-resistant.

One (12.5%) episode was caused by coagulase-negative

Staphylococcus (CoNS) and the other by

Mycobacterium chelonae (12.5%). The remaining

four (50%) episodes were culture-negative peritonitis

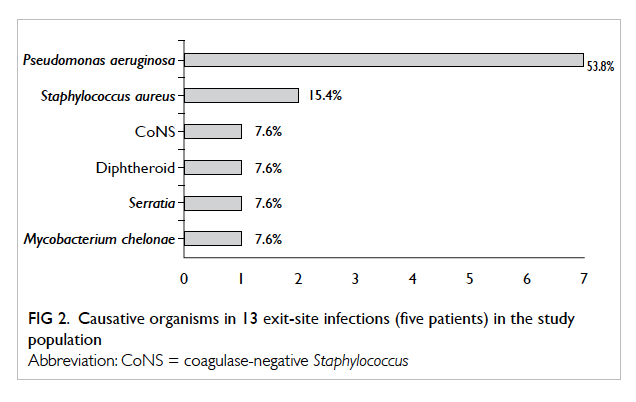

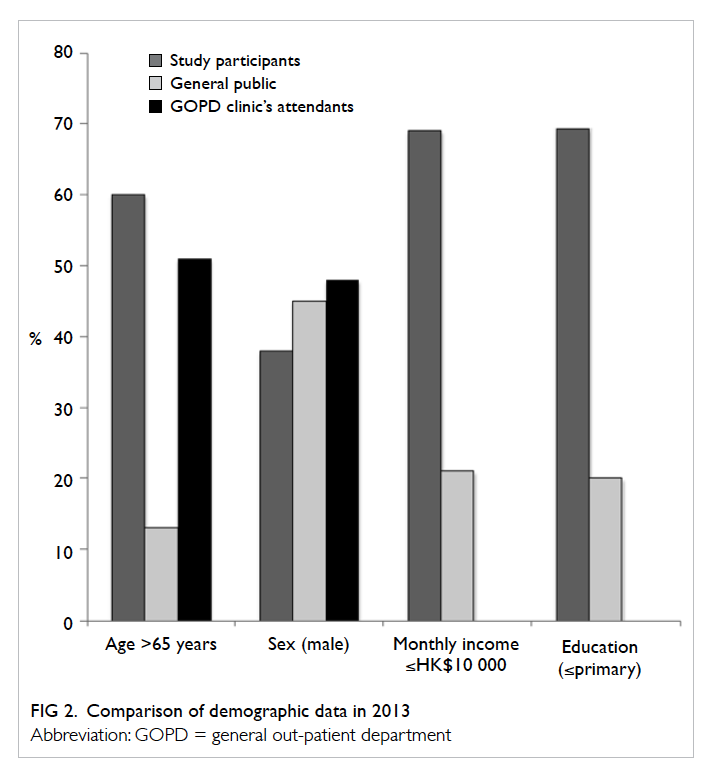

(Fig 1). Altogether 13 episodes of ESI occurred in five patients, and patient 3 contributed seven episodes.

The rate of ESI was 0.42 episode per patient-year

or 1 episode per 28.6 patient-months. The most

common organisms were Pseudomonas aeruginosa

(n=7, 54%) and methicillin-sensitive S aureus (n=2,

15%). Other causative pathogens included CoNS,

diphtheroid, Serratia, and M chelonae, each of which

resulted in one ESI (Fig 2).

One patient required surgical correction of

patent processus vaginalis that led to hydrocoele.

One patient required repair of bilateral inguinal

hernia. One patient had cuff extrusion and required

replacement of PD catheter. No catheters developed

leakage.

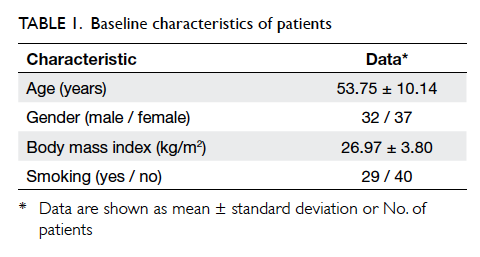

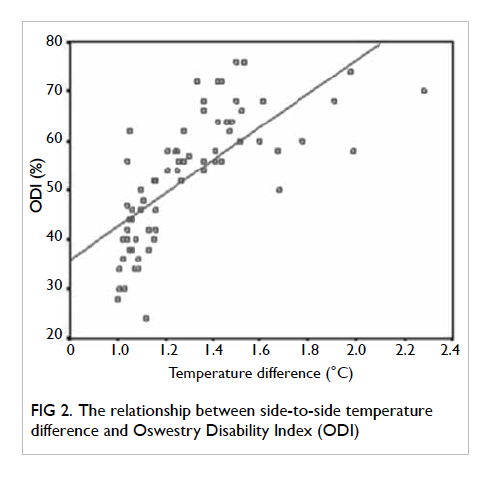

Growth and nutrition

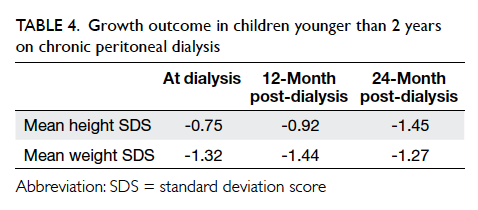

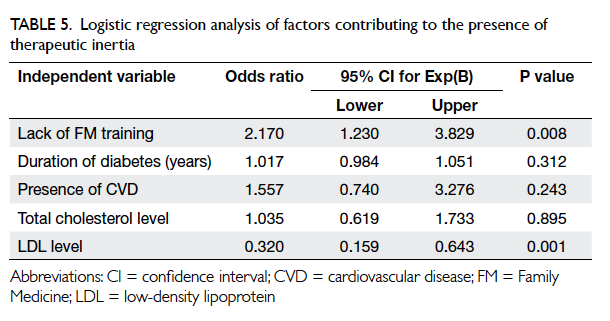

Weight gain was observed after initiation of CPD.

At the start of dialysis, 12 months and 24 months

post-dialysis, the mean weight SDS (wtSDS) was

-1.32, -1.44, and -1.27, while height SDS (htSDS) was

-0.75, -0.92, and -1.45, respectively (Table 4). Three (33%) patients were commenced on nasogastric

(NG) enteral feeding and eventually were switched

to gastrostomy feeding. Six (67%) patients were fed

on demand, one of whom was awaiting gastrostomy

insertion at the end of the study. Three (33%) patients

were prescribed growth hormone therapy before the

age of 2 years.

Development

Four (44%) children were delayed in development or

received special education. Two of them had severe

perinatal asphyxia associated with hypoxic ischaemic

encephalopathy, one was born prematurely at 32

weeks of gestation and the other had PH1, all of

which could account for the developmental delay.

Anaemia, chronic kidney disease–mineral bone disease, and hypertension

During the first 2 years of CPD, all patients received

erythropoiesis-stimulating agent, except patient 5

who later became dialysis-free. The mean maximum

dose of recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO)

was 169 ± 91 (range, 65-300) units/kg/week. Three

patients received rHuEPO at a dose exceeding 200

units/kg/week. Seven patients were put on oral

iron supplements; one of whom was switched to

intravenous iron replacement subsequently due to

functional iron deficiency. The mean haemoglobin

level was 109 ± 8 g/L; only two patients (patients 1

and 7) failed to achieve a mean haemoglobin level of

≥100 g/L.

All patients showed some degree of CKD-MBD,

as evidenced by raised PTH level and the

need for activated vitamin D and phosphate binder.

Five patients had severe renal osteodystrophy

with clinical or radiological manifestations (Table 2). All of them had markedly elevated mean

PTH (90-111 pmol/L) outside the recommended

target. Of note, two patients (patients 6 and 7)

had pathological fractures. Two patients (patients

7 and 9) received a calcimimetic (cinacalcet) for

tertiary hyperparathyroidism. Five (56%) patients

had hypertension and were on antihypertensive

medications with satisfactory control.

Outcome

All patients survived except patient 6 with PH1

who died of acute portal vein thrombosis following

liver transplantation at the age of 5 years. Patient 5

with pHUS became dialysis-free after 8.6 months

of CPD. Four patients underwent deceased donor

renal transplantation (DDRT) with a mean waiting

time of 76.7 (range, 54-90) months, of whom two

were switched to chronic haemodialysis before

transplantation because of inadequate dialysis. Three

patients remained on PD at the end of the study.

Discussion

End-stage renal disease is rare in infants and young

children. The reported incidence is variable but

remains low around the globe. Up to 16 cases per

age-related population per year have been reported

in the UK.13 In NAPRTCS 2011, 13.2% of children

on dialysis were under 2 years old.4 In Hong Kong,

recent data from the Hong Kong Renal Registry

showed that the incidence and prevalence of ESRD

in those <20 years old was around 5 and 28 per

million children, respectively.14

The most common aetiology of ESRD in

this age-group is congenital anomalies of the

kidney and urinary tract, including renal dysplasia

and obstructive uropathy.15 Nonetheless, pHUS

constituted an important cause of ESRD in Hong

Kong. A potential explanation is the late introduction

of a universal pneumococcal vaccination programme

in 2009, compared with 2000 in the US population.

In our study, all patients started with CPD.

Difficult vascular access for haemodialysis and a

high volume of daily milk intake make CPD the

more favourable choice of renal replacement therapy

in young infants. While local mean DDRT waiting

time in children younger than 18 years was 4.4 ±

2.4 years,16 the waiting time in our young patients

was much longer (mean, 6.4 years). This is because

patients have to weigh more than 15 kg before DDRT

can be carried out due to technical difficulties.

Therefore, CPD acts as a bridge to transplantation

and reserves vascular access for future use.15

Ethical considerations and infection, together

with growth and nutrition, are the most challenging

aspects of infant CPD.

Ethical considerations

Decisions to initiate or withhold dialysis remain

one of the most challenging aspects in infant

ESRD. Recent data, which showed improvement

in mortality and developmental outcome, support

initiation of dialysis. Shroff et al6 reported a survival

rate of 77% at 5 years in children commenced

on chronic dialysis before the age of 1 year. Our

unpublished data revealed 91 patients were put on

APD from 1996 to 2013. The overall survival rate was

90%. In this series, survival rate in young infants was

similar and there was no CPD-related mortality. The

only mortality resulted from surgical complications

after liver transplantation.

Warady et al17 reported the 79% infants who

started CPD had normal developmental scores at

1 and 4 years old and 94% of school-aged children

attended school. In our series, 44% of patients

were delayed in development, all of which could

be accounted for by co-morbidities or underlying

aetiology of ESRD.

Nonetheless, unpredictable outcome,

psychosocial burdens, and cost continually fuel

the ethical dilemma.13 15 18 The family burden is

tremendous. Since CPD is a home-based treatment,

caregivers must perform dialysis daily. Up to 55%

of paediatric nephrologists felt a parental decision

to refuse dialysis should be respected for neonates

and 26% for children of 1 to 12 months old.13 In

two surveys, serious co-existing co-morbidities and

predicted morbidity were the most important factors

when a physician considered withholding dialysis.1 19 While serious non-renal co-morbidities such as

pulmonary hypoplasia are strongly associated with a

poor prognosis,20 patients with isolated renal disease

should be considered separately as their prognosis

is generally better.18 It should be a shared decision-making

process between parents and paediatric

nephrologists, after detailed counselling on potential

burdens and after considering co-morbidities,

expected quality of life, and available resources

and expertise.18 21 Designated nurses, clinical

psychologists, and medical social workers are crucial

in supporting patients and parents.

Peritoneal dialysis–related infection

Infants and young children are at risk of PD-related

infectious complications. In the US, the annualised

rate of peritonitis in children younger than 2 years

was 0.79 episode per patient-year, compared with

0.57 episode per patient-year in adolescents aged over 12 years.4 In our

current series, the annual peritonitis rate was 0.26,

which is less frequent than the US data. As previously

reported, the overall annual peritonitis rate among

all our paediatric patients on APD was low at 0.22.22 A low infection rate has similarly been reported in several Asian countries.22

There are a few possible explanations. First, all

our patients were on APD that is associated with a

reduced risk of infection as shown in a systematic

review by Rabindranath et al23 and previous data in

NAPRTCS 2005.24 Second, we strictly complied with

the guidelines and recommendations on prevention

of PD-related infection.4 9 21 25 26 Measures included the use of double-cuffed Tenckhoff catheters,

downward or laterally pointing exit sites away

from diaper and ostomies, antibiotic prophylaxis

at catheter insertion, post-insertion immobilisation

of the catheter, nasal methicillin-resistant S aureus

screening and decolonisation with mupirocin, and

selective use of prophylactic topical antibiotics for

patients with a history of ESI. Third, all patients

and their carers completed an intensive PD training

programme before commencing home APD.

Training was conducted by a senior renal nurse

with regular reviews and phone follow-ups. The

high culture-negative peritonitis rate in our series

highlights the need for proper specimen collection

and handling.9

Growth and nutrition

Growth in infancy is important because one third of

postnatal height is achieved during the first 2 years

of life.27 Growth during this period largely relies on

nutritional intake, rather than growth hormone.

Growth in ESRD is often impaired because of poor

appetite, increased circulatory leptin, nutritional loss

through peritoneal dialysate and repeated vomiting

due to dysmotility, gastroesophageal reflux, and

raised intraperitoneal pressure.15 27 Infants can lose more than 2 htSDS that can be irreversible.15

Importantly, it is also a period of catch-up growth;

NAPRTCS reported improvement in both htSDS

and wtSDS in children who started dialysis before

the age of 2 years—htSDS improved from -2.59 at

baseline to -2.15 at 24 months post-dialysis, while

wtSDS improved from -2.26 to -1.05.4

In our cohort, there was weight gain, but a

decline in htSDS was observed. The IPDN recently

analysed growth in 153 very young children on CPD.27

Interestingly, htSDS decreased further in the first 6

to 12 months of CPD and then stabilised. Although

catch-up in height was noted in the NAPRTCS

report, such improvement was only observed in

children with worse baseline height deficit, defined as

htSDS ≤ –1.88. Children with htSDS > –1.88 instead

had a decline in htSDS by 0.11 and 0.2 at 12 and 24

months, respectively.4 Only two of our patients had

worse baseline height deficit (≤ –1.88), with htSDS

being -2 at CPD initiation. Similar to the findings in

IPDN and NAPRTCS, catch-up growth in height was

observed in these two patients. At 12 months post-dialysis,

their htSDS improved to -0.94 and -1.6, respectively.

Oral intake is often unsatisfactory and enteral

feeding is required, either by NG or gastrostomy

tube. This allows overnight feeding and reduces

vomiting. In the recent IPDN study on growth, 37%

young children were fed on demand, 39% by NG

tube, 7% by gastrostomy tube, and 17% switched

from NG to gastrostomy feeding.27 Both NG and

gastrostomy feeding led to significant increase in

body mass index SDS, although regional variation

was observed. Gastrostomy but not NG feeding was

associated with improved linear growth, an effect

that was no longer significant after adjusting the

baseline length. Feeding by gastrostomy appeared

to be superior to NG tube in growth promotion and

may be related to less vomiting.27

Over the years, the use of a gastrostomy

to enhance nutritional supplementation has

been promoted in our centre, with intensified

collaboration with a paediatric renal dietitian. In our

series, only one (20%) patient who commenced CPD

before 2008 received enteral feeding, owing to low

parental acceptance. Of the remaining four patients

who started CPD after 2008, two had gastrostomies,

one was awaiting gastrostomy insertion, and one

thrived satisfactorily without the need for enteral

feeding. This suggests an improved nutritional

management and parental acceptance. Extra efforts

should also be made to optimise factors such as

acidosis, anaemia, and metabolic bone disease.27

In addition, KDOQI (Kidney Disease Outcomes

Quality Initiative) suggests consideration of growth

hormone when children have htSDS and height

velocity SDS of ≤ –1.88 after optimising nutrition

and metabolic abnormalities.28

There are a few limitations to this study. First,

because of the retrospective study design, there was

recall bias. Some information could not be retrieved

from medical records, especially for children who

presented in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Second,

the total case number was small since patients were

recruited from a single nephrology centre. Last,

infant dialysis has changed considerably over the

past two decades and might in turn affect patient

outcome.

Conclusions

End-stage renal disease in very young children is

uncommon. Chronic PD is feasible and the outcome

is improving. Vigilant adoption of guidelines,

universal use of APD, and a well-structured PD

training programme are crucial to achieve low

peritonitis and ESI rates with no CPD-related

mortality in our centre. Optimisation of dialysis,

nutritional support, and developmental training are

important while successful renal transplantation is

the ultimate goal for these infants.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Geary DF. Attitudes of pediatric nephrologists to

management of end-stage renal disease in infants. J Pediatr

1998;133:154-6. Crossref

2. Kari JA, Gonzalez C, Ledermann SE, Shaw V, Rees L.

Outcome and growth of infants with severe chronic renal

failure. Kidney Int 2000;57:1681-7. Crossref

3. Ledermann SE, Scanes ME, Fernando ON, Duffy PG,

Madden SJ, Trompeter RS. Long-term outcome of

peritoneal dialysis in infants. J Pediatr 2000;136:24-9. Crossref

4. North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative

Studies (NAPRTCS). 2011 Annual dialysis report. Available from: https://web.emmes.com/study/ped/annlrept/annualrept2011.pdf. Accessed Nov 2015.

5. Vidal E, Edefonti A, Murer L, et al. Peritoneal dialysis in

infants: the experience of the Italian Registry of Paediatric

Chronic Dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:388-95. Crossref

6. Shroff R, Rees L, Trompeter R, Hutchinson C, Ledermann

S. Long-term outcome of chronic dialysis in children.

Pediatr Nephrol 2006;21:257-64. Crossref

7. Warady BA, Alexander SR, Hossli S, et al. Peritoneal

membrane transport function in children receiving long-term

dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 1996;7:2385-91.

8. Warady BA, Alexander S, Hossli S, Vonesh E, Geary

D, Kohaut E. The relationship between intraperitoneal

volume and solute transport in pediatric patients. Pediatric

Peritoneal Dialysis Study Consortium. J Am Soc Nephrol

1995;5:1935-9.

9. Warady BA, Bakkaloglu S, Newland J, et al. Consensus

guidelines for the prevention and treatment of catheter-related

infections and peritonitis in pediatric patients

receiving peritoneal dialysis: 2012 update. Perit Dial Int

2012;32 Suppl 2:S32-86. Crossref

10. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)

CKD-MBD Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice

guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and

treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone

Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl 2009;113:S1-130.

11. Borzych D, Rees L, Ha IS, et al. The bone and mineral

disorder of children undergoing chronic peritoneal dialysis.

Kidney Int 2010;78:1295-304. Crossref

12. Leung SS, Tse LY, Wong GW, et al. Standards for

anthropometric assessment of nutritional status of Hong

Kong children. Hong Kong J Paediatr 1995;12:5-15.

13. Rees L. Paediatrics: Infant dialysis—what makes it special?

Nat Rev Nephrol 2013;9:15-7. Crossref

14. Yap HK, Bagga A, Chiu MC. Pediatric nephrology in Asia.

In: Avner ED, Harmon WE, Niaudet P, Yoshikawa N,

Emma F, Goldstein SL, editors. Pediatric nephrology. 6th

ed. Springer; 2010: 1981-90.

15. Zaritsky J, Warady BA. Peritoneal dialysis in infants and

young children. Semin Nephrol 2011;31:213-24. Crossref

16. Chiu MC. An update overview on paediatric renal

transplantation. Hong Kong J Paediatr 2004;9:74-7.

17. Warady BA, Belden B, Kohaut E. Neurodevelopmental

outcome of children initiating peritoneal dialysis in early

infancy. Pediatr Nephrol 1999;13:759-65. Crossref

18. Lantos JD, Warady BA. The evolving ethics of infant

dialysis. Pediatr Nephrol 2013;28:1943-7. Crossref

19. Teh JC, Frieling ML, Sienna JL, Geary DF. Attitudes of

caregivers to management of end-stage renal disease in

infants. Perit Dial Int 2011;31:459-65. Crossref

20. Wood EG, Hand M, Briscoe DM, et al. Risk factors for

mortality in infants and young children on dialysis. Am J

Kidney Dis 2001;37:573-9. Crossref

21. Zurowska AM, Fischbach M, Watson AR, Edefonti A,

Stefanidis CJ, European Paediatric Dialysis Working

Group. Clinical practice recommendations for the care

of infants with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD5).

Pediatr Nephrol 2013;28:1739-48. Crossref

22. Chiu MC, Tong PC, Lai WM, Lau SC. Peritonitis and exit-site

infection in pediatric automated peritoneal dialysis.

Perit Dial Int 2008;28 Suppl 3:S179-82.

23. Rabindranath KS, Adams J, Ali TZ, Daly C, Vale L,

MacLeod AM. Automated vs continuous ambulatory

peritoneal dialysis: a systematic review of randomized

controlled trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007;22:2991-8. Crossref

24. North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative

Study (NAPRTCS). 2005 Annual report. Available

from: https://web.emmes.com/study/ped/annlrept/annlrept2005.pdf. Accessed Nov 2015.

25. Piraino B, Bailie GR, Bernardini J, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related

infections recommendations: 2005 update. Perit

Dial Int 2005;25:107-31.

26. Auron A, Simon S, Andrews W, et al. Prevention of

peritonitis in children receiving peritoneal dialysis. Pediatr

Nephrol 2007;22:578-85. Crossref

27. Rees L, Azocar M, Borzych D, et al. Growth in very young

children undergoing chronic peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc

Nephrol 2011;22:2303-12. Crossref

28. KDOQI Work Group. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline

for Nutrition in Children with CKD: 2008 update.

Executive summary. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;53:S11-104. Crossref