Serological response to mRNA and inactivated COVID-19 vaccine in healthcare workers in Hong Kong: decline in antibodies 12 weeks after two doses

Hong Kong Med J 2021 Oct;27(5):380–3 | Epub 18 Oct 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Serological response to mRNA and inactivated

COVID-19 vaccine in healthcare workers in Hong Kong: decline in antibodies 12 weeks after two doses

Jonpaul ST Zee, FRCPath, FHKAM (Medicine)1,2; Kristi TW Lai, MMedsc (HKU)1; Matthew KS Ho, MMedSc (HKU)1; Alex CP Leung, MMedSc (HKU)1; LH Fung, MPhil3; WP Luk, MPhil3; LF Kwok, BSc (Nursing)4; KM Kee, MPH4; Queenie WL Chan, BScN, FHKAN (Medicine-Infection Control)2; SF Tang, FHKCPath, FHKAM (Pathology)1,2; Edmond SK Ma, MD, FRCPath1; KH Lee, MMedSc (HKU), FHKAM (Community Medicine)5; CC Lau, MB, BS, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)5; Raymond WH Yung, MB, BS, FHKCPath1,2,5

1 Department of Pathology, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Infection Control Team, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Medical Physics and Research Department, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong

4 Quality and Safety Division, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong

5 Hospital Administration, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Jonpaul ST Zee (jonpaul.st.zee@hksh.com)

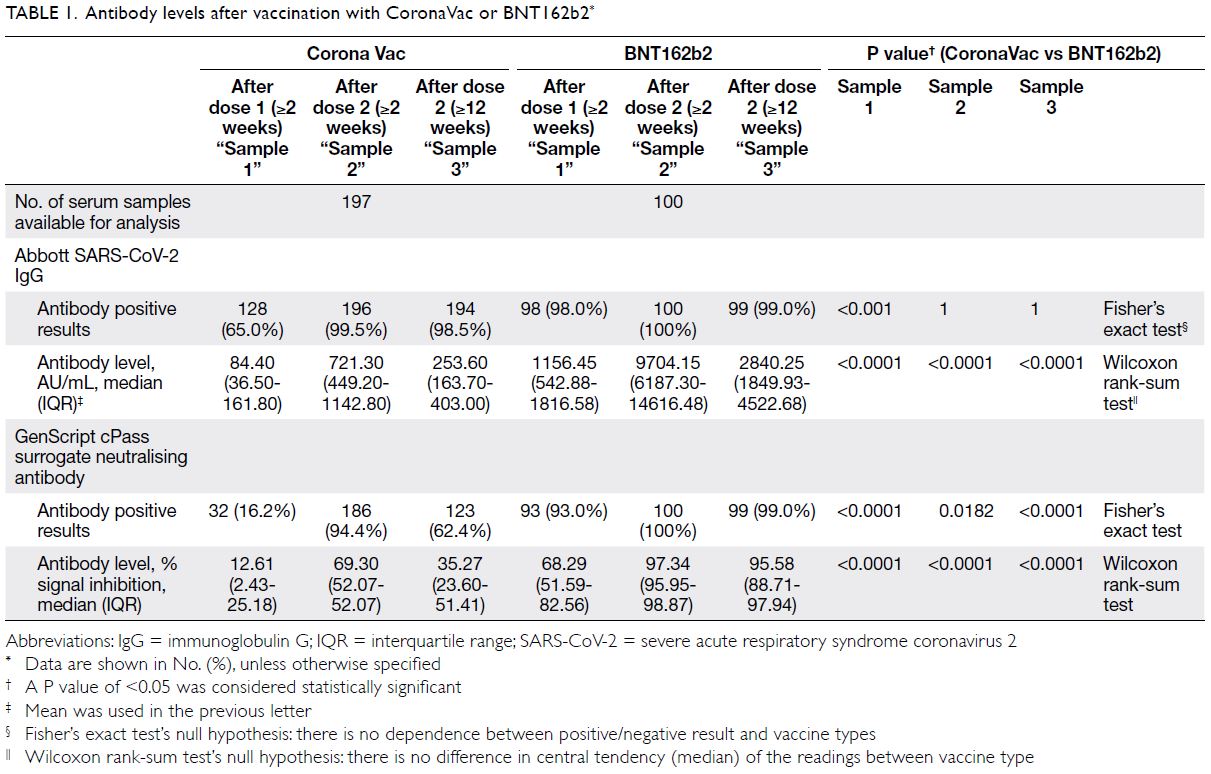

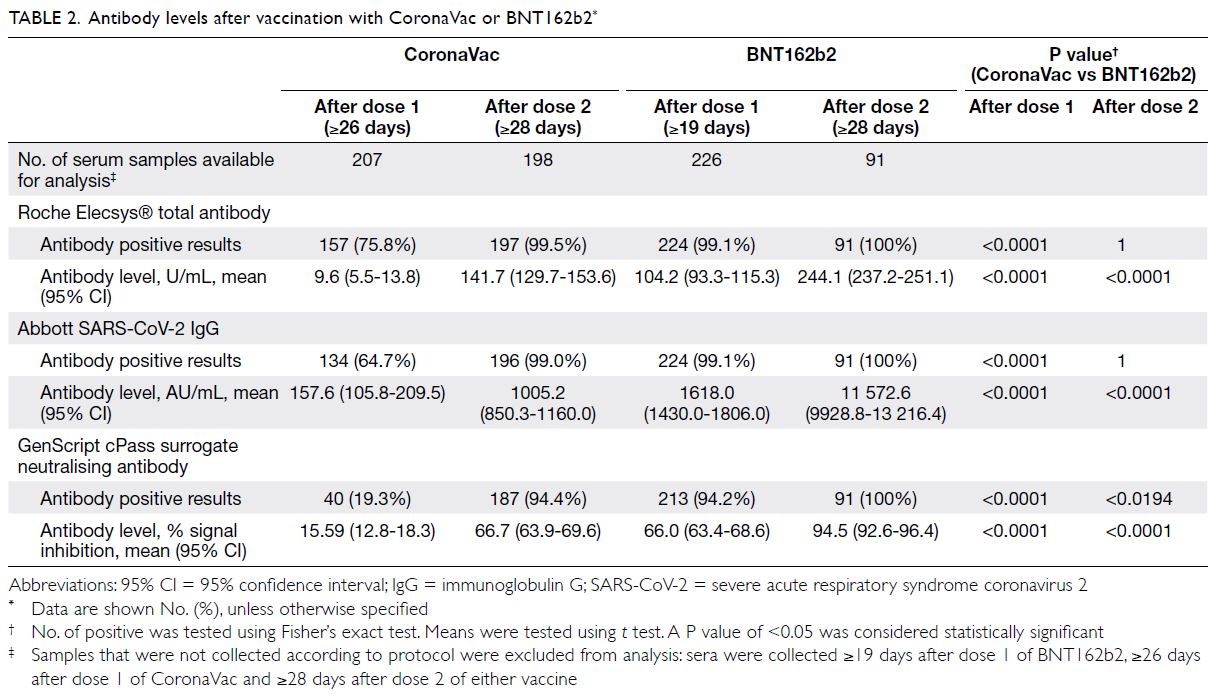

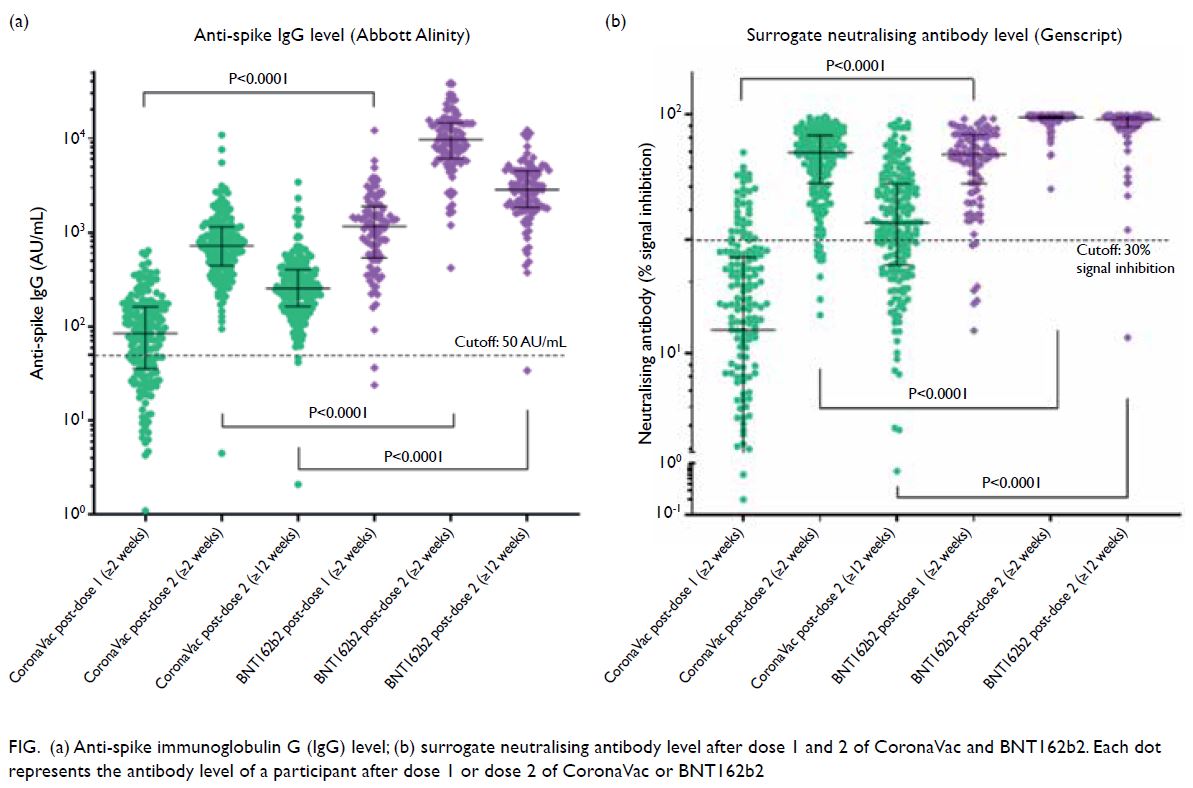

To the Editor—We previously reported serological

findings of 302 healthcare workers (HCWs) who

completed two doses of mRNA (BNT162b2/Comirnaty; Fosun-BioNTech Pharma) and inactivated COVID-19 vaccine (CoronaVac; Sinovac

Life Sciences, Beijing, China).1 Both vaccines were found to be immunogenic in the majority of HCWs.

The BNT162b2 resulted in a 11-fold higher level of

anti-spike IgG (Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG II Quant

assay, mean=11572.6 AU/mL vs 1005.2 AU/mL;

P<0.001) and a higher surrogate neutralising

antibody (sNAb) [GenScript cPass SARS-CoV-2

Surrogate Virus Neutralization Test Kit] positive

rate (100% vs 94.4%; P<0.001).

We report week 12 serological data of our

cohort. Among 197 CoronaVac and 100 BNT162b2

recipients, baseline characteristics of the two vaccine arms were comparable except sex (60.9%

and 38% female in CoronaVac and BNT162b2,

respectively) [online supplementary Table 1]. There

was no difference in anti-spike immunoglobulin G

(IgG) positive rate at week 12 (98.5% in CoronaVac

vs 99% in BNT162b2; P=1) [Table 1]. Waning of IgG

level was observed in both vaccine arms with a larger

magnitude of decline in BNT162b2 (-72% vs -64.6%;

P<0.001). Despite the more pronounced decline,

the median anti-spike IgG of BNT162b2 remained

11-fold higher than that of CoronaVac at week 12

(2840.25 AU/mL vs 253.60 AU/mL; P<0.001).

Decline in sNAb was also observed in both

arms but the magnitude was significantly smaller

in BNT162b2 (-28.3% in CoronaVac vs -2.3% in

BNT162b2; P<0.001). Using the manufacturer’s

positive cut-off at 30% signal inhibition or above, significantly more CoronaVac recipients had lost

their sNAb at week 12 (94.4% sNAb positive at week

2, 62.4% at week 12) whereas 99% of BNT162b2

recipients remained sNAb positive. Throughout the

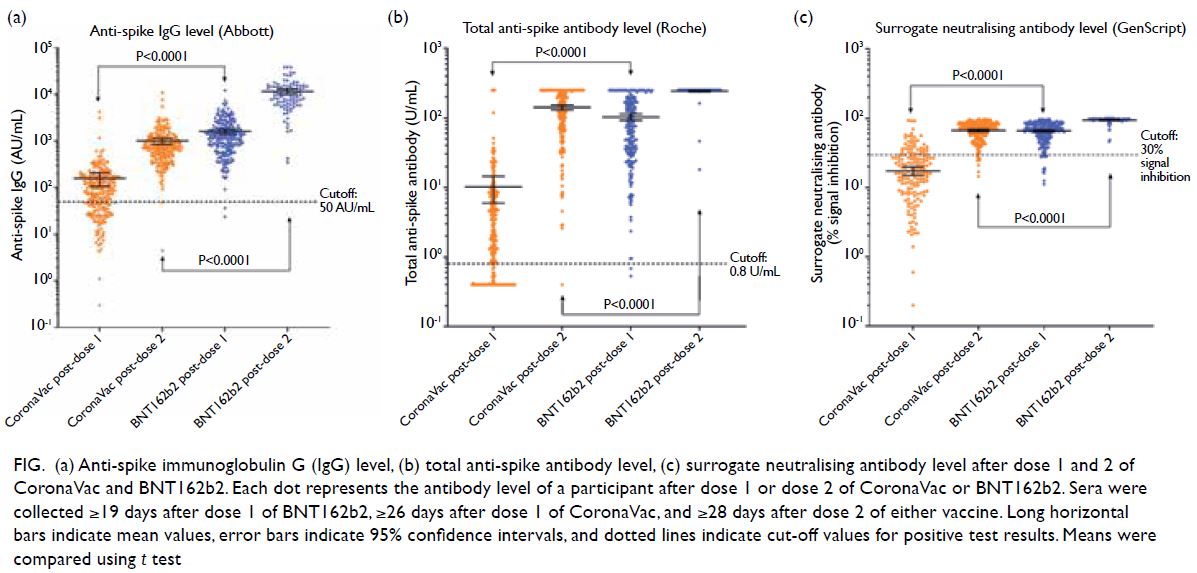

three time points, BNT162b2 arm had higher levels

of anti-spike IgG and sNAb (P<0.001) [Fig].

Figure. (a) Anti-spike immunoglobulin G (IgG) level; (b) surrogate neutralising antibody level after dose 1 and 2 of CoronaVac and BNT162b2. Each dot represents the antibody level of a participant after dose 1 or dose 2 of CoronaVac or BNT162b2

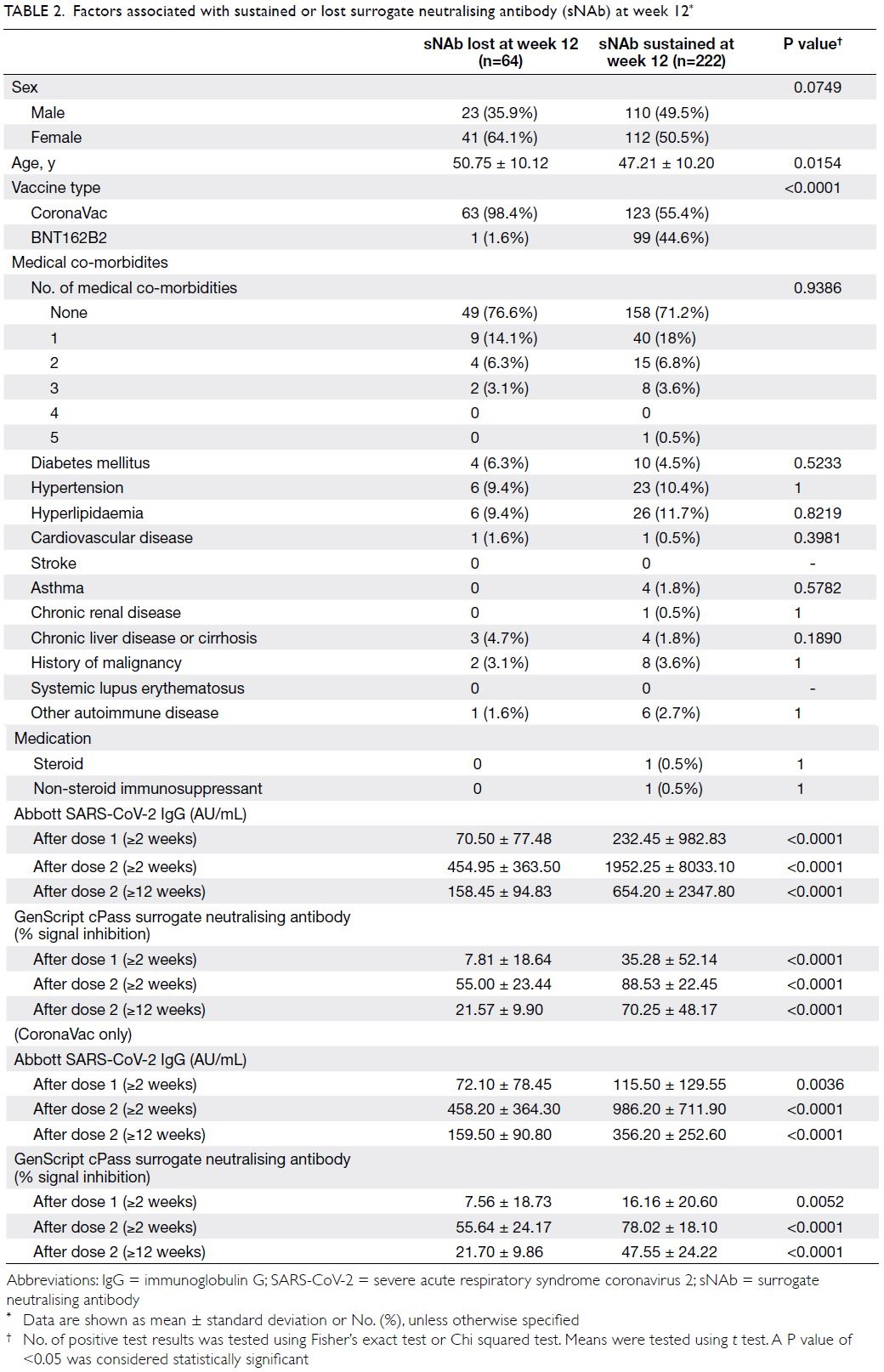

Among the 286 HCWs who had positive

sNAb after two doses of vaccine, 64 had lost their

sNAb while 222 had sustained sNAb at week 12.

Sustained sNAb at week 12 were associated with

younger age, BNT162b2 and higher antibody at

any time point (Table 2). Multivariate logistic

regression analysis showed that only higher IgG and

sNAb level at 2 weeks after the second dose were

significantly associated with sustained sNAb at week

12 (online supplementary Table 2).

Table 2. Factors associated with sustained or lost surrogate neutralising antibody (sNAb) at week 12

These results demonstrate rapid antibody

decline after both mRNA and inactivated vaccine

with a more durable sNAb in the BNT162b2 arm.

However, further studies are needed to clarify the

impact of waning antibody on vaccine efficacy and

protection against severe infection.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: JST Zee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: JST Zee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the excellent work and contributions by staff at the Clinical Pathology Laboratory of Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital.

Funding/support

This letter received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study obtained ethics approval (Ref RC-2021-07) from the Research Ethics Committee of the Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital Medical Group.

Reference

1. Zee JS, Lai KT, Ho MK, et al. Serological response to mRNA and inactivated COVID-19 vaccine in healthcare workers in Hong Kong: preliminary results. Hong Kong

Med J 2021;27:312-3. Crossref