Uterine compression sutures for management of severe postpartum haemorrhage: five-year audit

Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:113–20 | Number 2, April 2014 | Epub 21 Oct 2013

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Uterine compression sutures for management of

severe postpartum haemorrhage: five-year audit

Victoria YK Chai, MB, BS, MRCOG; William

WK To, MD, FRCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology,

United Christian Hospital,

Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr WWK To (towkw@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To audit

the use of compression

sutures for the management of massive postpartum

haemorrhage and compare outcomes to those

documented in the literature.

Design: Retrospective

study.

Setting: A regional

obstetric unit in Hong Kong.

Patients: Patients with

severe postpartum

haemorrhage encountered over a 5-year period

from January 2008 to December 2012, in which

compression sutures were used for management.

Main outcome measures: Successful

management

with prevention of hysterectomy.

Results: In all, 35

patients with massive postpartum

haemorrhage with failed medical treatment, for

whom compression sutures were used in the

management, were identified. The overall success

rate for the use of B-Lynch compression sutures alone

to prevent hysterectomy was 23/35 (66%), and the

success rate of compression sutures in conjunction with other

surgical procedures was 26/35 (74%).

This reported success rate appeared lower than that

reported in the literature.

Conclusion: Uterine

compression was an effective

method for the management of massive postpartum

haemorrhage in approximately 70% of cases,

and could be used in conjunction with other

interventions to increase its success rate in terms of

avoiding hysterectomy.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Compression sutures are effective in the management of postpartum haemorrhage arising from uterine atony as well as placenta praevia.

- In an unselected case series audit in a regional obstetric training unit, the efficacy of uterine compression sutures appeared to be lower than that reported in the literature.

- Uterine compression sutures should be adopted as part of the management of severe postpartum haemorrhage in local obstetric units. Contingent treatment protocols for further interventions should be available if compression sutures fail.

Introduction

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a serious

and

life-threatening obstetric complication. It is usually

defined as an estimated blood loss of more than

500 mL after delivery and occurs in around 5% of

all deliveries.1 As

increased maternal morbidity

and morbidity are associated with further blood

loss, alternative definitions for severe PPH,

such as estimated blood loss exceeding 1000

mL, are commonly used in various guidelines.2

Conventionally, the first-line treatment options

for PPH include conservative management with

uterotonic drugs (oxytocin or prostaglandins),

while second-line therapy includes uterine packing,

external compression with uterine sutures, selective

devascularisation by ligation, or embolisation of the uterine

artery.3 4 5 6 7 These

various treatment

modalities have been included as an integral part of

the HEMOSTASIS management algorithm widely

advocated in the UK.8 The

use of such measures

should reduce the need for hysterectomy, which is

associated with further blood loss and additional

morbidity.9

The B-Lynch suture has been the most

wellestablished

compression suture technique since

reporting of the first published series in 1997, and

described oversewing of the uterus with a continuous

suture to apply ongoing compression.4

Since then,

the technique has been adopted for control of

bleeding in severe PPH due to uterine atony as well

as placenta praevia/accreta.10

11 Modifications of the

original technique, as well as various other suturing techniques,

have since been advocated.5

12 13 14

The

current case series described the use of compression

sutures in the management of massive PPH that

failed to respond to medical therapy over a review

period of 60 months encountered in a single obstetric

training and service unit of the Hong Kong Hospital

Authority. The compression suture techniques

employed in this series were the basic B-Lynch

or the slightly modified Bhal technique.15

Various

associated prognostic factors were assessed and

compared to evaluate whether they could predict

success or failure.

Methods

A retrospective review of all patients

having a

severe PPH over a 60-month period (January 2008

to December 2012 inclusive) was performed, based

on details logged in a comprehensive obstetric

database currently used in all Hospital Authority

obstetric units. Specific codings for “primary PPH”,

“compression sutures of uterus”, “caesarean section

with hysterectomy”, and “peripartum hysterectomy”

were searched for and identified from the clinical

management system of the hospital. Cases of

severe PPH with blood loss exceeding 1 L were also

identified from the Labour Ward registry. The case

notes or operative records of each of these patients

were also reviewed to verify whether management

entailed use of compression suturing techniques.

All identified cases where compression sutures had

been used or their use attempted were then reviewed in detail for

the mode of delivery, intrapartum

complications, cause of the PPH, sequence of

treatment modalities used, estimated total blood

loss, any complications resulting from the different

manoeuvres, and clinical outcome.

The application of the B-Lynch suture was

in accordance with the original description with

the hysterectomy wound still open, using either

Monocryl or Vicryl No.1 sutures in accordance

with the surgeon’s preference. In some cases,

two separate sutures were applied instead of one

continuous suture as described by Bhal et al.15 All

patients had an indwelling Foley catheter to monitor

urine output, and broad-spectrum antibiotics were

used for prophylaxis. All patients who had severe

haemorrhage treated by intra-operative transfusions

and all who had evidence of coagulopathy were

admitted to the intensive care unit after their

operation.

Results

There were a total of 26 029 deliveries

over the review

period. The point prevalence of primary PPH with

estimated blood loss exceeding 500 mL was 3.2%

(n=825), and that exceeding 1 L (severe PPH) was

105/26 029 (0.4%). Among the latter, 33 had vaginal

delivery and 72 caesarean sections; 25 of these

patients were managed by medical treatment alone.

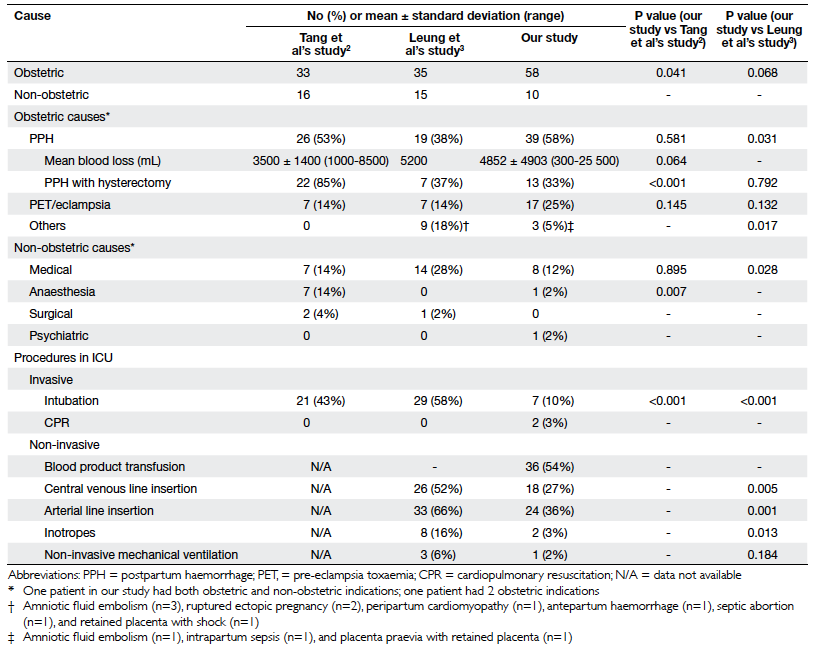

Regarding the remaining 80 patients with severe

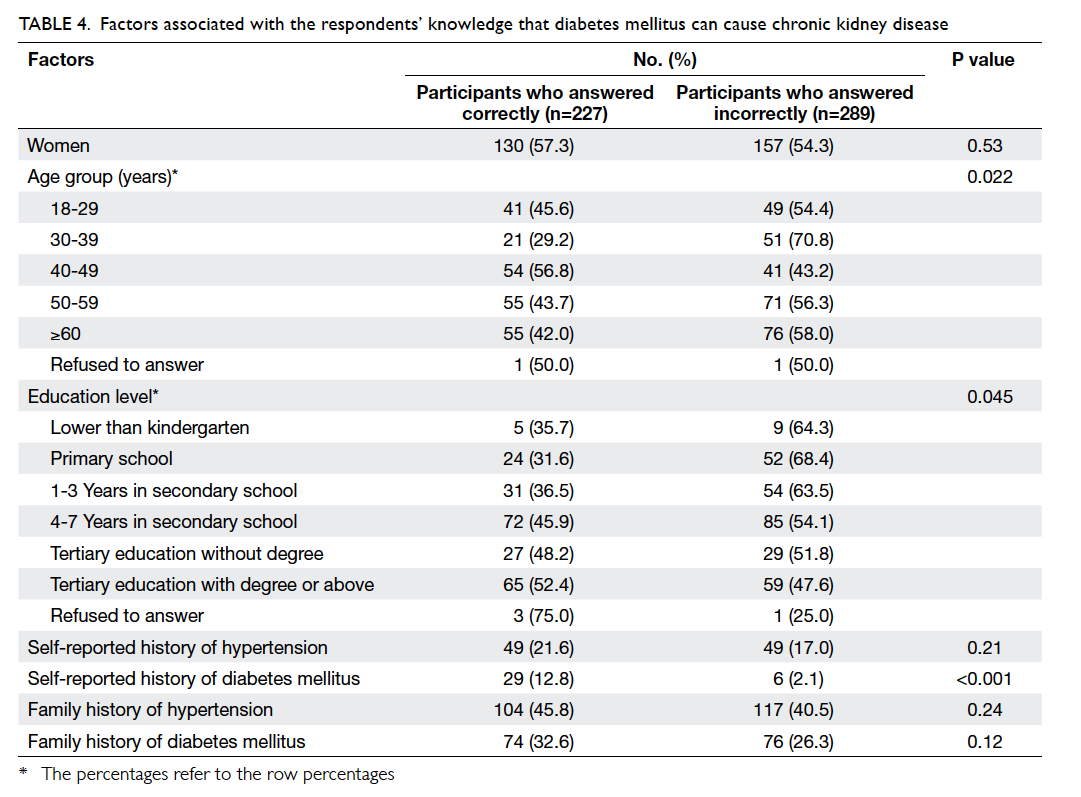

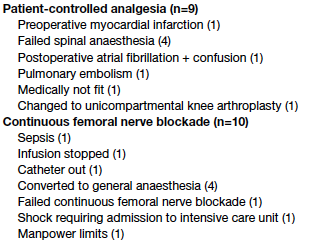

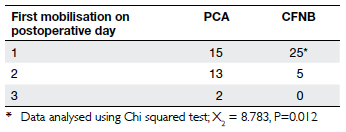

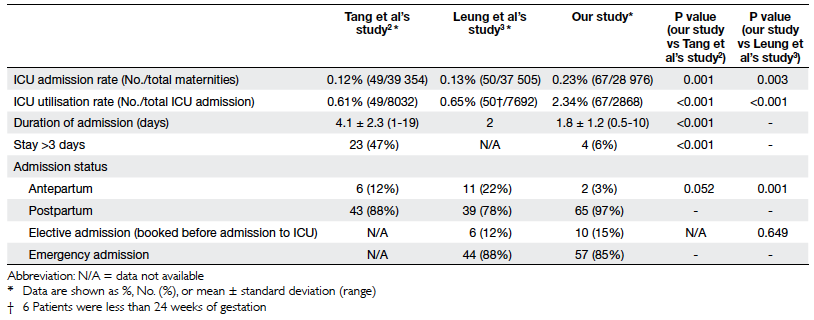

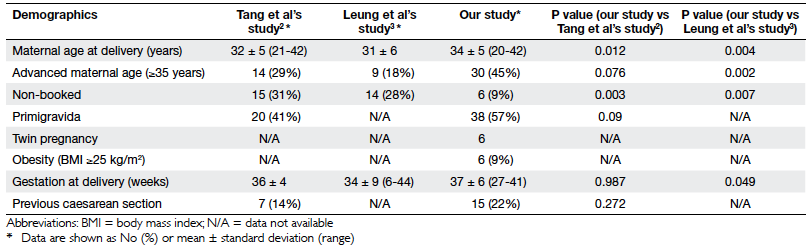

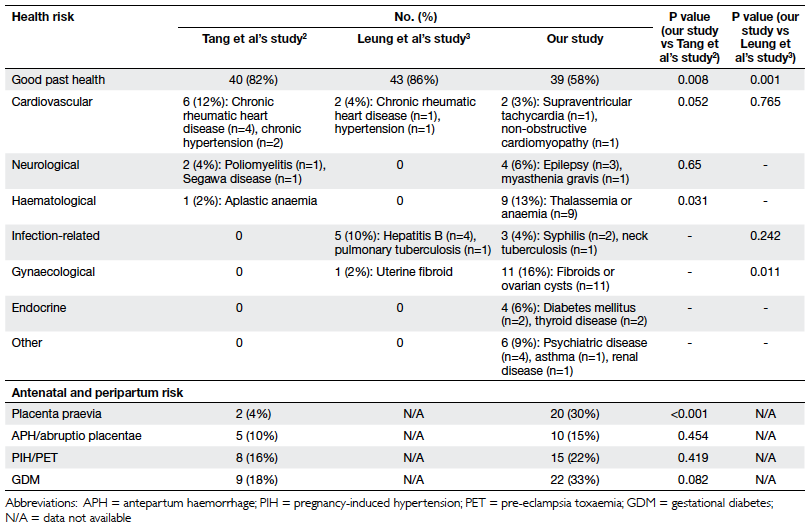

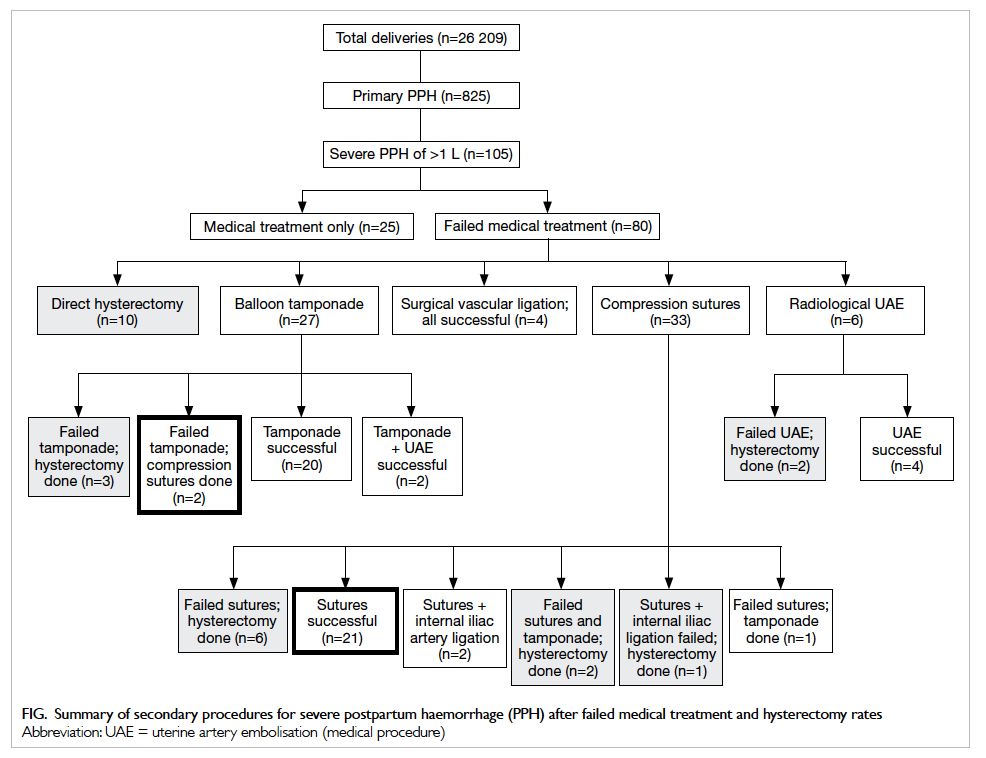

PPH, their management is shown in the Figure.

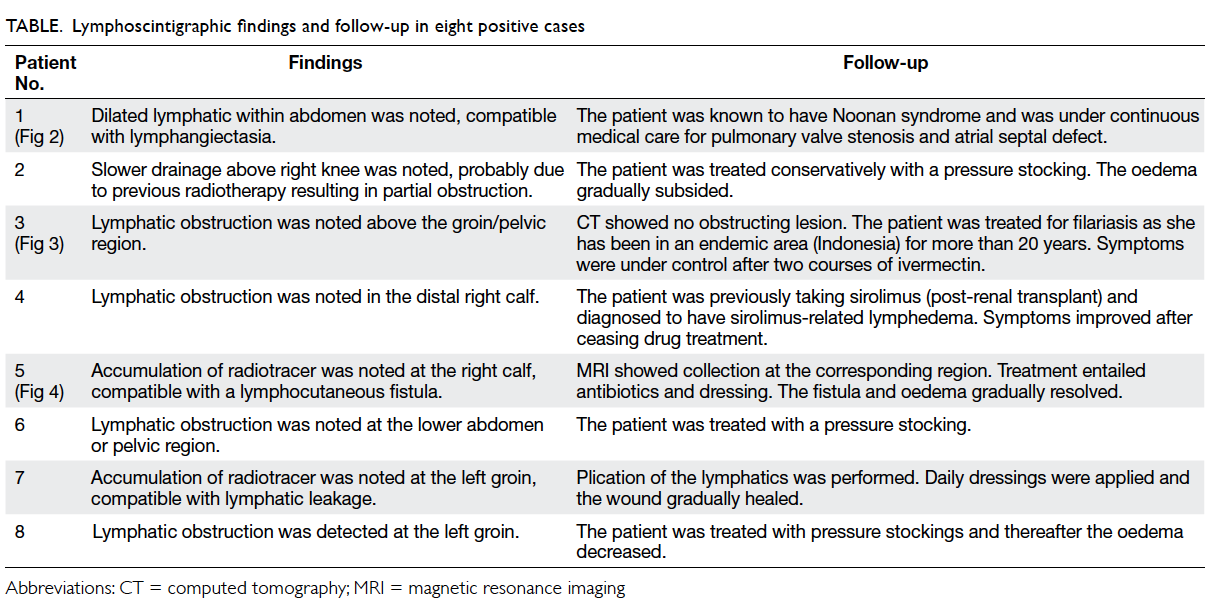

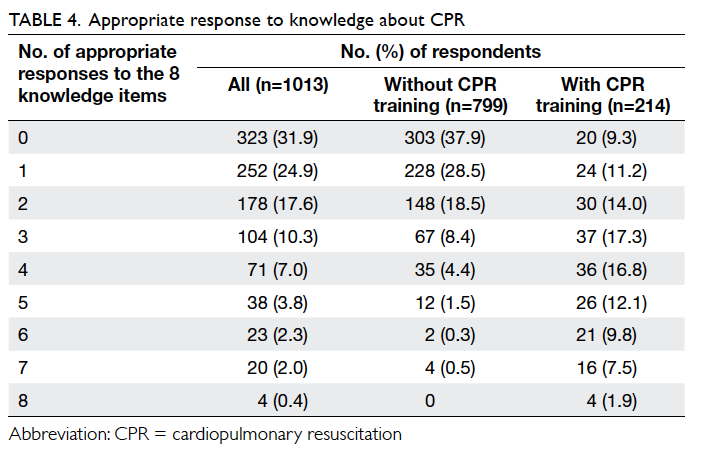

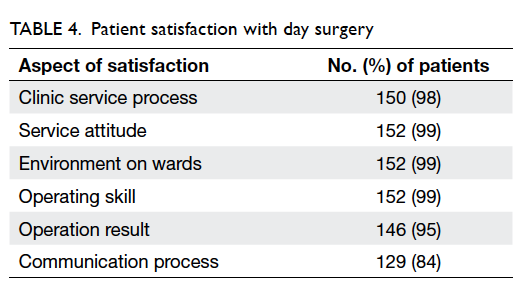

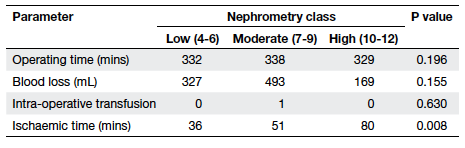

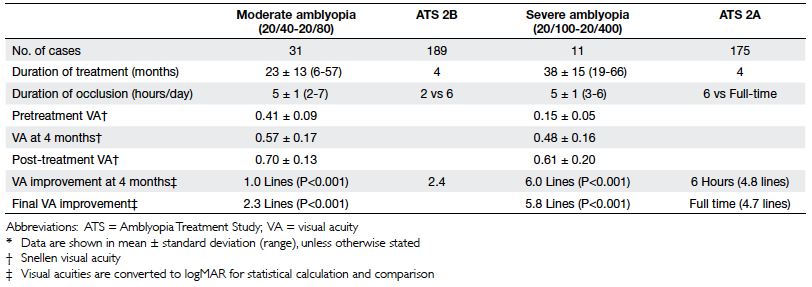

Figure. Summary of secondary procedures for severe postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) after failed medical treatment and hysterectomy rates

Within this study period, there were 24

peripartum hysterectomies, of which nine involved

attempted use of compression sutures and were

included in this case series. The other 15 cases

included the 10 who had an a priori hysterectomy (6

for placenta praevia/accreta, 4 for intractable uterine

atony) without resort to other more conservative

procedures, two for uterine atony with failed

treatment following radiological uterine arterial

embolisation, and three who had hysterectomy when

attempted intrauterine balloon tamponade failed

to control the bleeding. Cases that did not entail

recourse to uterine compression sutures were not

analysed any further.

All the identified cases of PPH that

involved

the use of compression sutures had failed initial

medical management with oxytoxics, including

bolus syntometrine, syntocinon bolus or infusion,

intramuscular carboprost injections, and in nine

cases, additional intramyometrial carboprost

injections. The most common aetiology of PPH

was uterine atony (28/35), followed by major

placenta praevia (7/35), and the total estimated

intra-operative blood losses of 1000 to 9300 mL.

Approximately 80% (28/35) of the patients were

deemed to require intra-operative blood product

transfusion, and disseminated intravascular

coagulopathy was documented in at least 13 (37%) of them. In one

patient (No. 3), attempted Bhal sutures

failed to arrest the bleeding from uterine atony, and

subtotal hysterectomy was performed. She had a

stump haematoma and massive stump bleeding 3

days later, for which the cervical stump was removed.

The bladder was perforated and despite immediate

repair at operation, she subsequently developed a

vesico-vaginal fistula that was surgically repaired 2

months after the hysterectomy. This was the only

patient in our series with major organ trauma. There

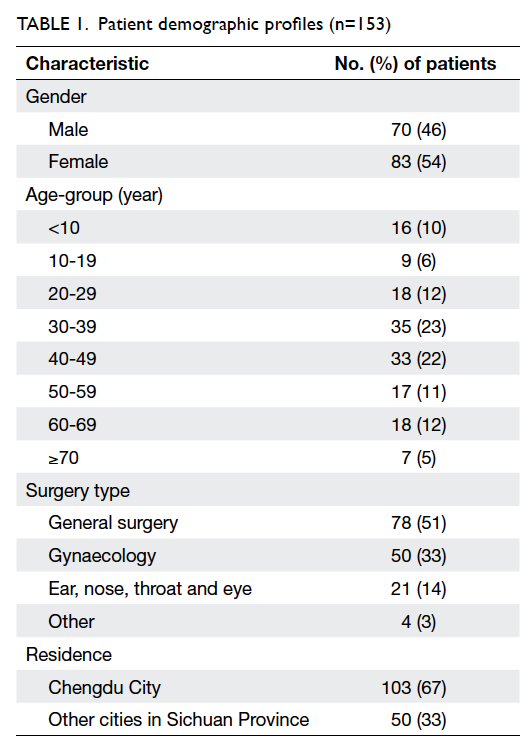

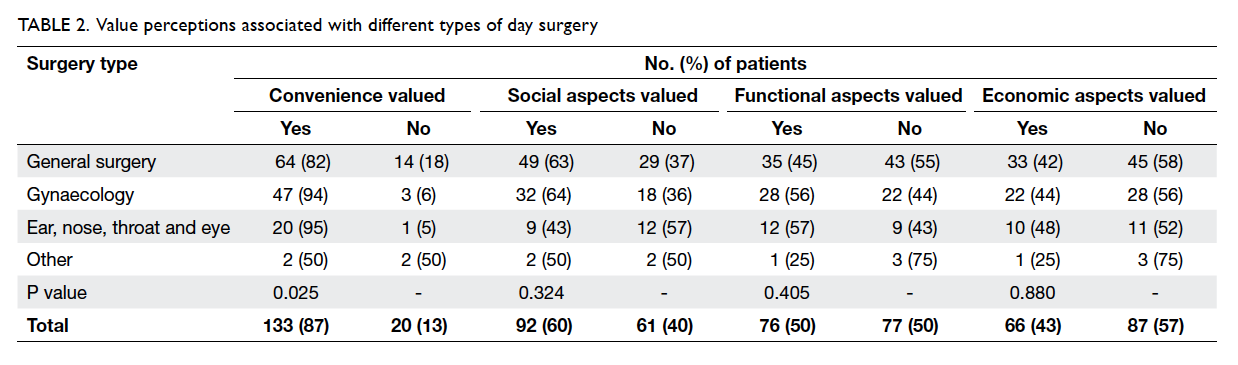

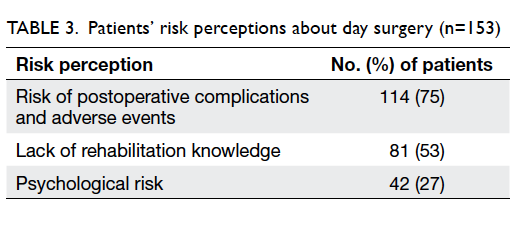

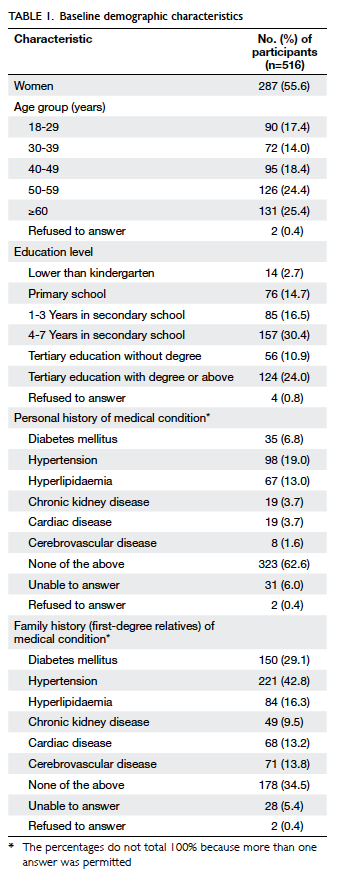

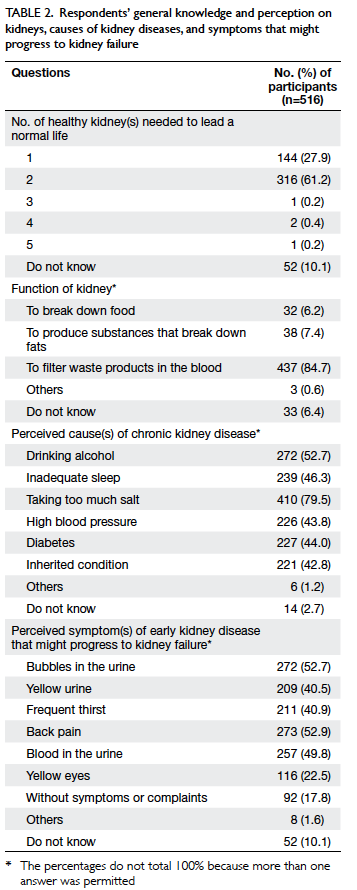

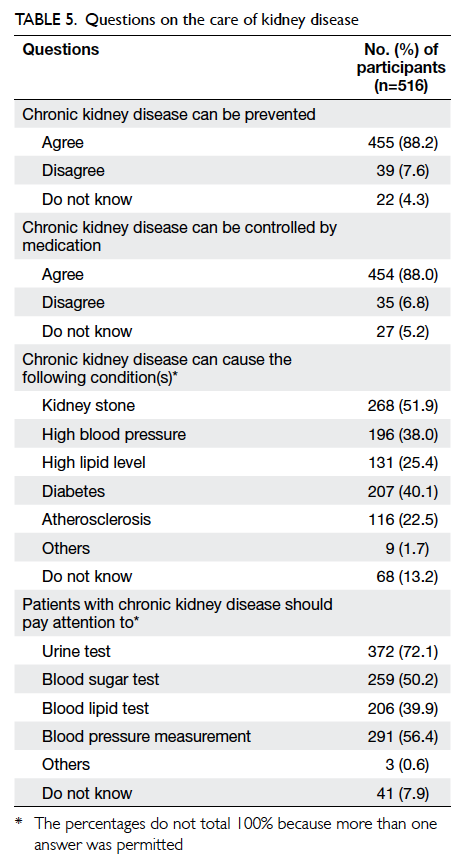

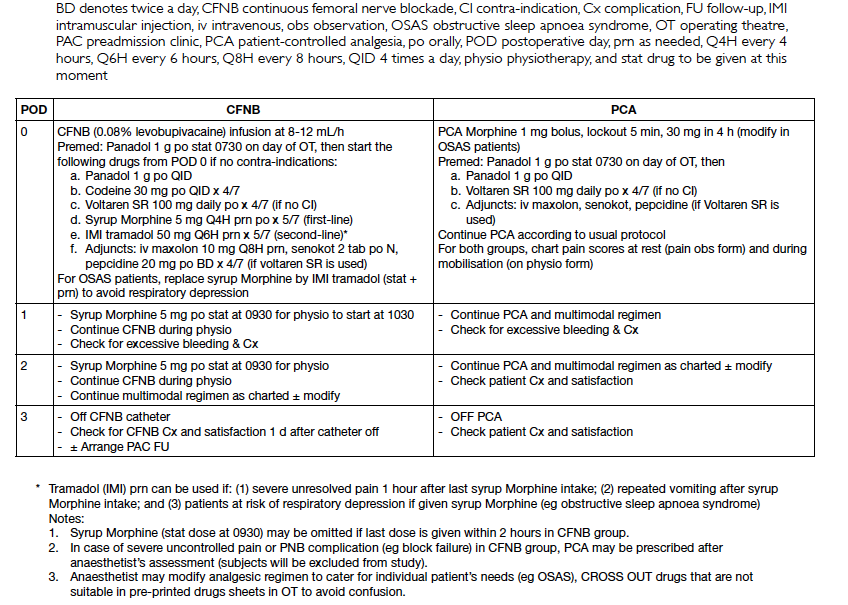

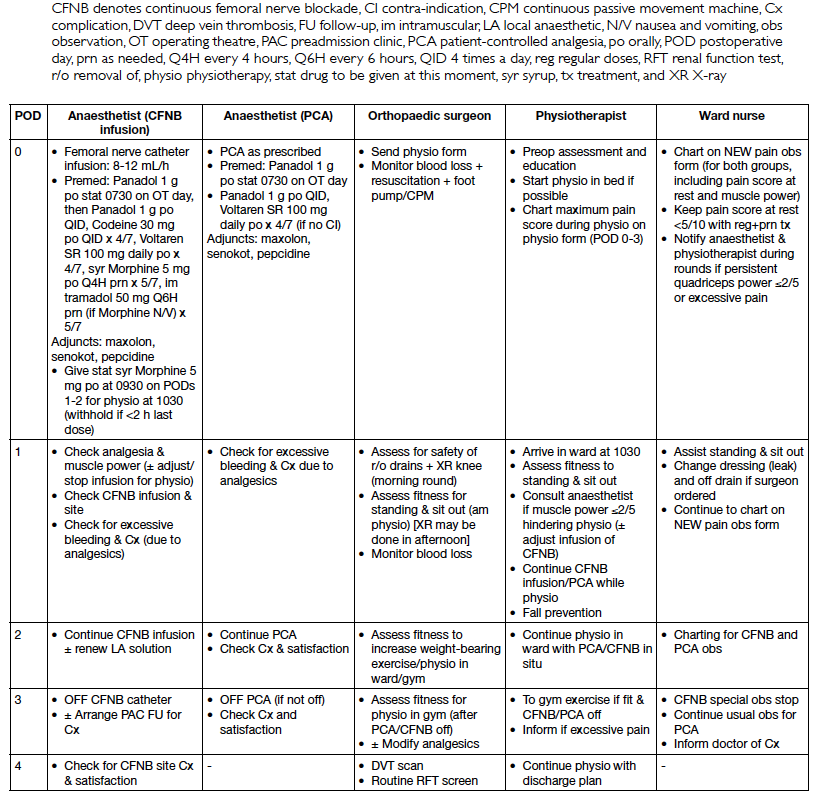

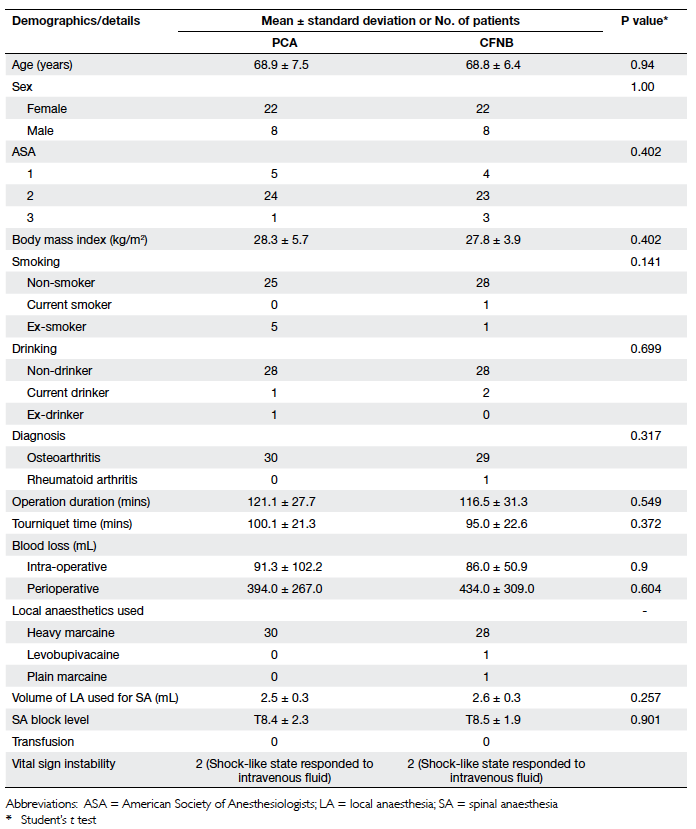

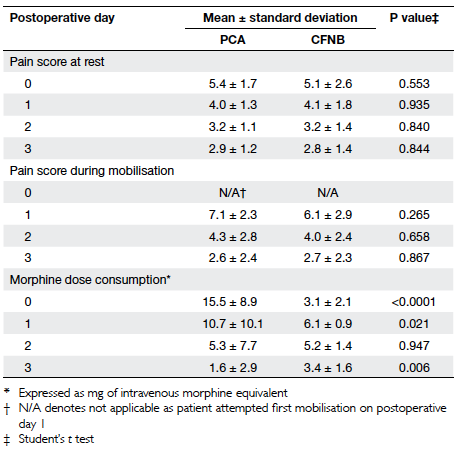

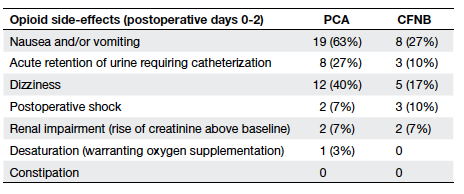

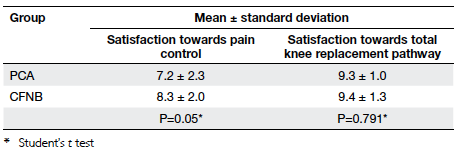

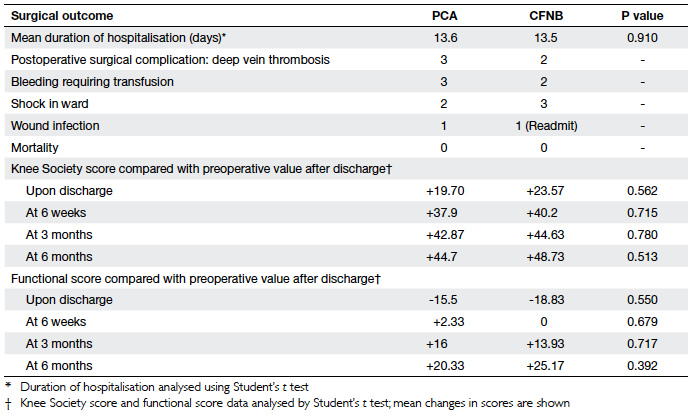

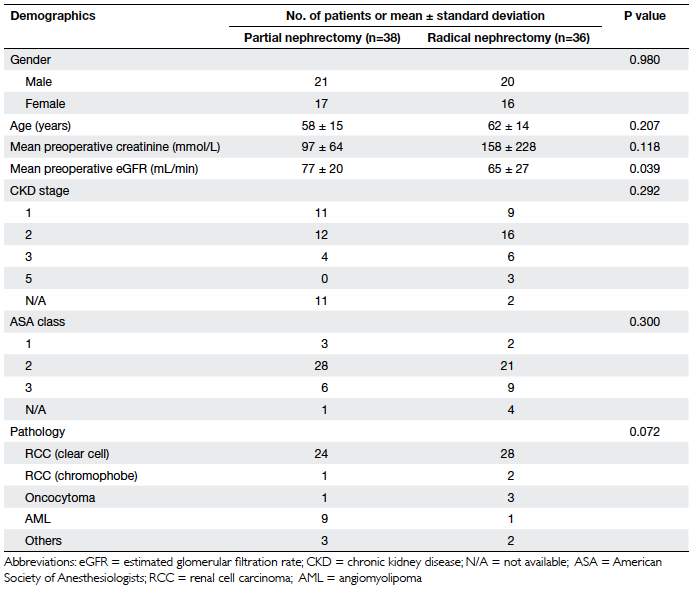

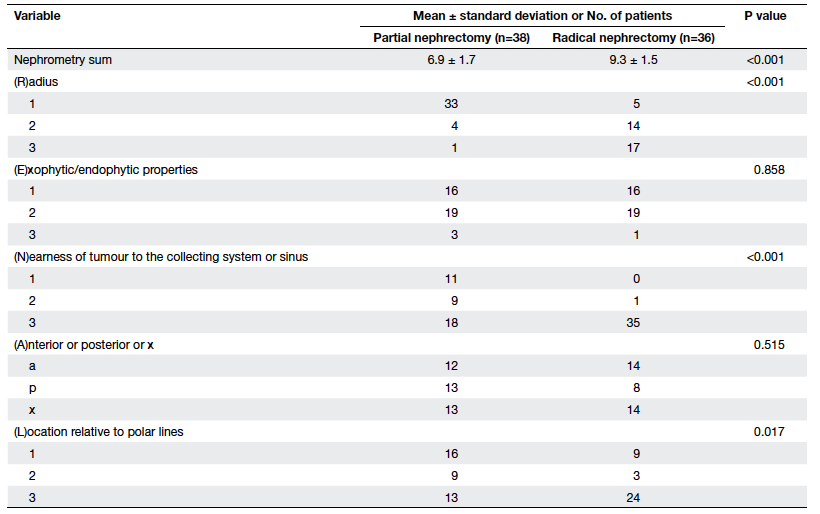

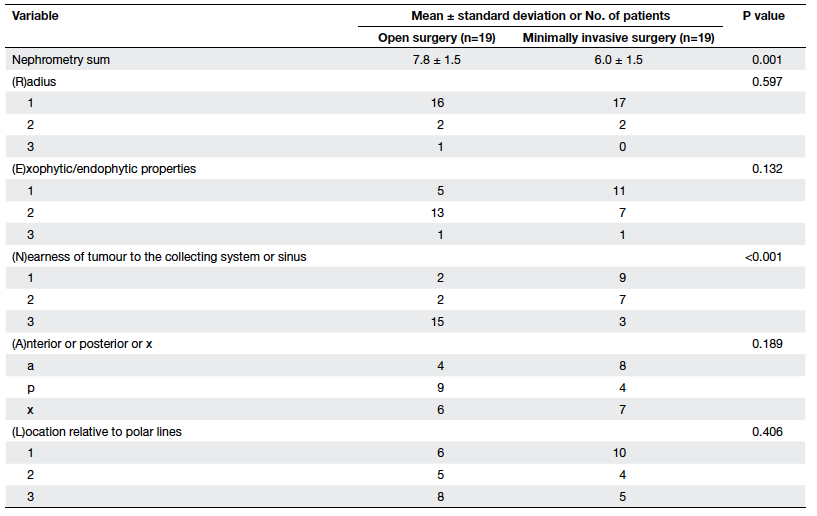

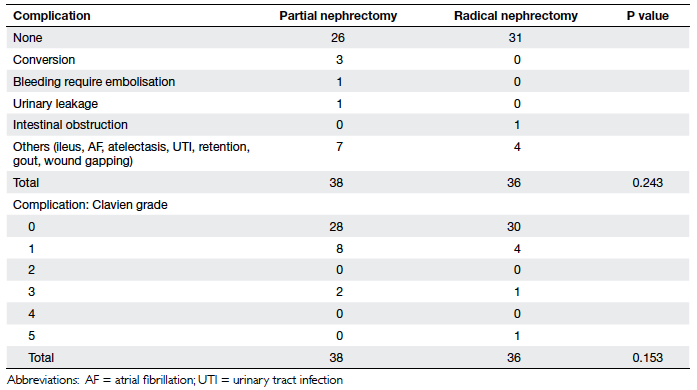

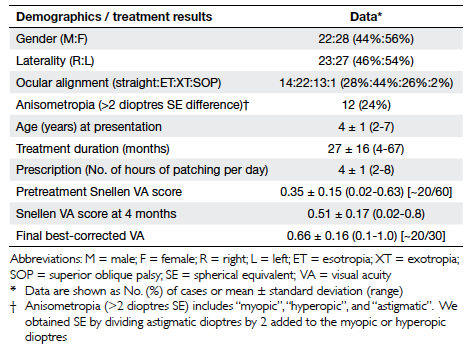

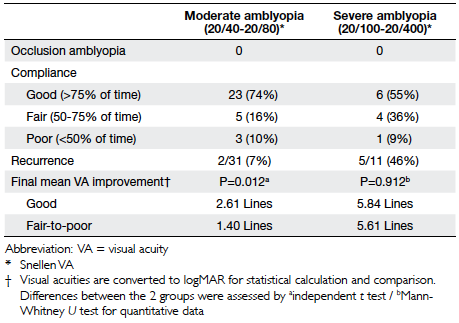

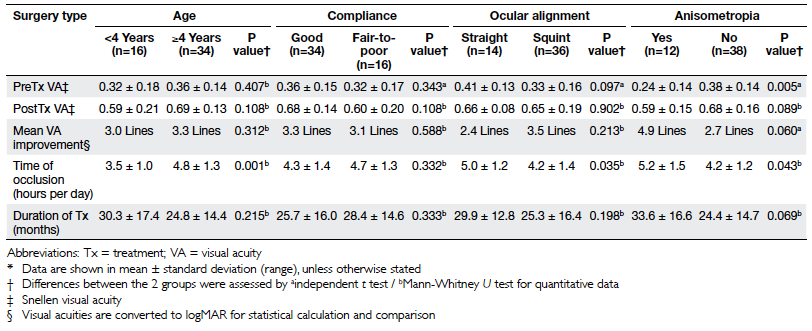

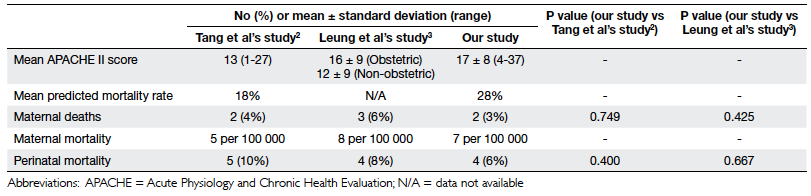

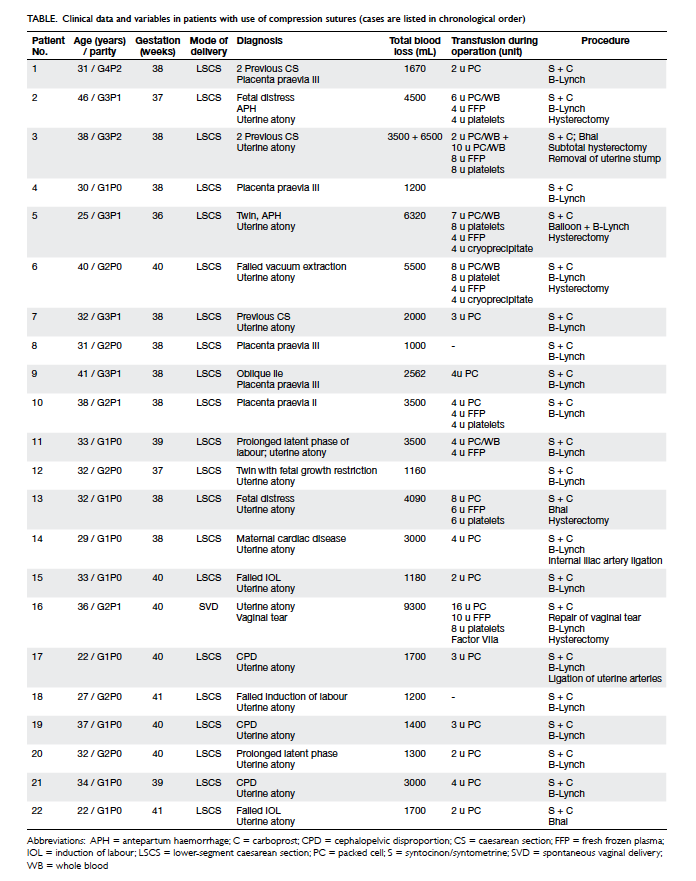

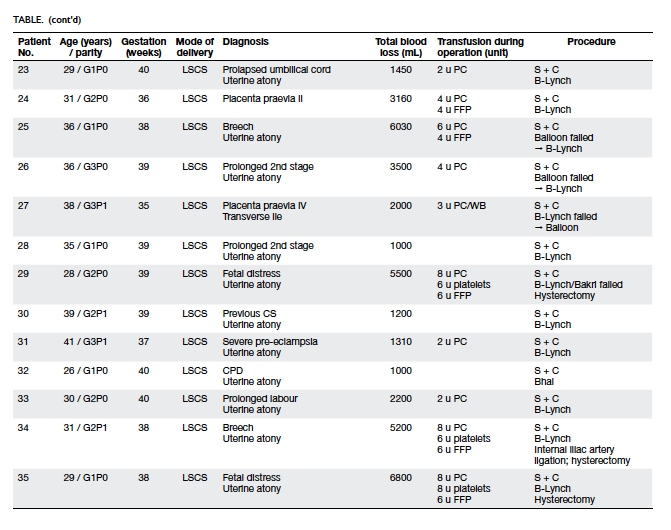

was no maternal mortality (Table: left, right).

Table. Clinical data and variables in patients with use of compression sutures (cases are listed in chronological order)

One patient (No. 16) had a normal vaginal

delivery followed by massive PPH despite oxytoxics.

Examination under anaesthesia was performed, and

vaginal tears were repaired. Laparotomy and B-Lynch

sutures were applied because of concurrent uterine

atony, but hysterectomy was finally performed. This

patient had the highest estimated blood loss (9.3 L)

in our case series and was the only one given Factor

VIIa for coagulopathy management.

Compression sutures were attempted together

with intrauterine balloon tamponade in five cases. In one patient

(No. 5) with uterine atony after caesarean

section for twin pregnancy, abdominal placement

of a Bakri balloon (for tamponade) was attempted

but failed to arrest the bleeding. The balloon was

removed and compression sutures were applied but

to no avail, and so a hysterectomy was performed.

In another patient with uterine atony following

caesarean section for fetal distress (No. 29), when

balloon tamponade failed to arrest bleeding, an

attempt to add on B-Lynch sutures in the form of a

“sandwich”16 led to

puncturing of the balloon, and so

a hysterectomy was performed. In two others with

uterine atony after caesarean section, abdominal

placement of a Bakri balloon failed to control

bleeding, but a B-Lynch suture was effective (Nos.

25 and 26). In a third patient (No. 27) with major

placenta praevia, B-Lynch sutures failed to arrest

haemorrhage. The sutures were therefore removed

and a Bakri balloon inserted via the hysterotomy

wound, and successfully controlled bleeding into the

lower uterine placental bed.

In two patients with uterine atony after

caesarean section (Nos. 14 and 17), continuous

bleeding from the vagina was observed after

application of B-Lynch sutures, and thus ligation

of the internal iliac arteries/uterine arteries was

performed with effective outcome. In a third

patient (No. 34), internal iliac artery ligation failed

to control the haemorrhage, and so a hysterectomy

was performed. Four other patients (Nos. 2, 6, 13,

and 35) failed to have their bleeding controlled by

compression sutures and underwent hysterectomies.

Thus, in our series the overall success

rate of

compression sutures alone as the primary second-line

(n=21) or rescue procedure (n=2) to prevent

hysterectomy was 23/35 (66%). The success rate

of compression sutures in conjunction with other

second-line procedures (two with iliac artery ligation

and one with intrauterine balloon tamponade) was

26/35 (74%). Specifically, when the aetiology of the

PPH was taken into consideration, the success rate

for B-Lynch compression sutures in patients with

uterine atony was 17/28 (61%) and that for placenta praevia cases

it was 6/7 (86%). The Bhal suture was

used in four cases only (Nos. 3, 13, 22, and 32) and its

success rate of 50% was not statistically significantly

different from that of B-Lynch sutures.

Particular putative patient risk factors

that

could reliably predict the success of compression

sutures as a means of avoiding hysterectomy included

age, parity, mode of delivery, operator experience,

aetiology of the PPH, and the extent of blood loss

at that time. Based on a multivariate stepwise

regression analysis, no significant risk factors for the

success of compression sutures could be identified in

the current data set.

Discussion

In this series, we were able to avoid

hysterectomy with

the use of uterine compression sutures, either alone

or in combination with other surgical interventions,

in only around 70% of patients with severe PPH. This

success rate was lower than that reported in many

other reported case series.4

5 11 12 13 14 17 18 19 20 21

The first description of uterine compression

sutures was published in 1996 as a single case

report from Zurich,22 which was followed by the

famous report of five consecutive cases utilising the

B-Lynch suture in 1997.4 Various modifications of

the B-Lynch suture, and various other compression

suture techniques have been reported since then.

In 2000, Cho et al13 described a haemostatic

multiple square suture to approximate the anterior

and posterior uterine wall. In 2002, Hayman et al5

proposed a uterine compression suture that involved

two vertical apposition sutures together with two

transverse horizontal cervico-isthmic sutures. In

2005, Hwu et al14 described the use of two parallel

vertical compression sutures placed in the lower

segment to control bleeding from placenta praevia.

These sutures compressed the anterior and posterior

uterine wall without penetrating the full thickness

of the posterior wall. Another modification was the

Pereira suture reported in 2005, which consisted

of longitudinal and transverse sutures applied with

superficial intramyometrial bites only.17 In the current

case series, the only modification to the B-Lynch

suture utilised was the Bhal technique.15 This entailed

two sutures instead of one, with the knots tied in

the anterior-inferior margin of the lower uterine

segment, without any difference in the compression

effects compared to the original B-Lynch suture. It

can be seen that the principle, namely, compression

of the uterine body, remains basically the same for all

types of compression sutures. The main differences

being the figure at which the suture is applied, the

numbers of longitudinal and/or transverse sutures

used, and whether or not the uterine cavity is

penetrated.23

In the literature, some series have described

compression sutures solely used for placenta

praevia/accreta,11 14 18 24 while others detailed their

use exclusively for atonic uteruses,19 20 and still

others referred to application of the technique to all

aetiologies.4 21 Apart from compressing the uterine

body in uterine atony, the original paper on the

B-Lynch suture also advocated its use for placenta

praevia. It was proposed that the sutures would

exert longitudinal compression and achieve evenly

distributed tension over the uterus, including the

lower segment.25 In addition, for cases of major

placenta praevia, B-Lynch also described the use

of additional independent figure-of-eight sutures

placed either anteriorly, posteriorly, or both on the

lower segment prior to suture application.4 Our

results from this series confirm the effectiveness of

the B-Lynch suture for patients with uterine atony

and placenta praevia.

Very high success rates with compression

sutures, usually in the range of 90﹪ to 100%, have

been reported since the first paper by B-Lynch in

1997.4 However, many of these reports had very small sample sizes (single case reports or cohorts of

15-20 patients).13 26 In recent years, larger case series

started to be reported. One of the largest published

series described experience from India, and reported

a success rate of 94% (45 out of 48 patients) using

Hayman sutures for PPH due to uterine atony.19 That

series did not include cases with placenta praevia/

accreta.19 Another interesting case series consisted

of a single surgeon’s experience in Argentina over a

20-year period, and involved 539 cases of excessive

obstetric bleeding from a variety of causes, including

uterine atony, placenta praevia/accreta, cervical scar

pregnancies as well as uterine/vaginal/cervical tears.21

Various surgical methods (often in combination) were

utilised to treat these cases, and the overall success rate

in those having the B-Lynch suture was 94% (81/86),

while for Hayman sutures, Cho sutures, and Pereira

sutures, the rates were 92% (34/37), 100% (37/37), and

100% (11/11), respectively.21 The very high success

rates reported in this personal series could be ascribed

to excellent surgical skills, optimal patient selection,

and choice of procedures by a super-specialist, but

may be difficult to reproduce elsewhere.

An earlier systematic review published in 2007

reported a success rate for uterine compression

sutures ranging from 68﹪ to 100% with an overall

success rate of 92%.6 Another review in 2010 compared

success rates of 95﹪ to 100% with eight different types

of compression sutures.27 However, both reviews

were based on case series with relatively small patient

numbers, which might indicate a reporting bias and

probably exaggerated the proportions with positive

outcomes. Interestingly, another review published in

2010 that focused on the long-term complications of

compression sutures and attempted to sum outcomes

with B-Lynch sutures from 32 separate case series.23

This reported an overall hysterectomy (failure) rate of

70/174 (40%), which was higher than most individual

case series.23

In this series, the mode of delivery was vaginal

in only one case (3%), the rest being delivered by

caesarean section (97%). This was likely due to a

bias in case selection in our practice. In patients

with severe PPH not delivered by caesarean section,

compression sutures were probably not the first-choice

surgical treatment due to consideration for

laparotomy and opening a hysterotomy wound.

Apparently, methods such as balloon tamponade28

were more common and convenient. The original

intrauterine Bakri balloon was designed to control

bleeding in patients with PPH caused by low-lying

placenta praevia/accreta.29 It could be inserted

easily and rapidly, without the need for laparotomy,

and under minimal anaesthesia. It can also be used

as a ‘tamponade test’ to aid decisions regarding

proceeding to laparotomy.3 Of the 27 cases of severe

PPH with balloon tamponade as the first- or second-line

procedure within our review period (Fig), 10 (37%) had vaginal delivery. Our experience with

the use of balloon tamponade has recently been

published in another case series.30

We were unable to identify any reliable

factors that would predict the success or failure of

compression sutures in this case series, possibly due

to the small size of our sample. Nor could we offer any

coherent hypothesis to explain our lower success rate

compared with that reported in the literature. As an

obstetric specialist is available on-site in our hospital

24 hours a day, specialist involvement was initiated

promptly in the management of all our cases. The 35

compression suture procedures were performed by

a total of eight surgeons with very similar training

and experiences in compression suture techniques.

They all used a relatively standard technique with

standard suture materials, and with standard

anaesthetic and transfusion support in accordance

with our hospital protocol. As compression sutures

placed for prophylactic purposes were not included

in this cohort, and all sutures were applied only in

the presence of severe PPH, the unselected nature

of our cases could have contributed to the lower

success rate. We believe that a success rate of around

70% would likely reflect the practical experience in a

general regional obstetric training unit locally.

Major complications of B-Lynch and other

compression sutures have been repeatedly described

in the literature. Cases of uterine necrosis presenting

several weeks post-delivery finally culminating

in total or subtotal hysterectomy have been

reported.31 32 Uterine necrosis was apparently the

result of ischaemia produced by compression sutures.

Haematometra might present with amenorrhoea33

and pyometria coupled with abdominal pain and

fever, weeks or months postpartum.34 The occurrence

of uterine cavity synechiae causing uterine outflow

obstruction has also been reported after compression

sutures, though infrequently.35 The combination of

compression sutures and additional vessel ligation

appeared more likely to cause complications such

as ischaemia and inflammation, but so far no deaths

have been reported in association with compression

sutures.23

Apart from compression suture and balloon

tamponade techniques, various fertility-preserving

methods had been employed for patients with PPH,

including pelvic devascularisation and radiological

arterial embolisation. Pelvic devascularisation

includes ligation of uterine artery and internal

iliac artery, but such techniques require surgical

expertise to apply and may be time-consuming.

Complications such as broad-ligament haematoma,

peripheral nerve ischaemia, and inadvertent ligation

of the lower limb arteries have been reported.36 37

Radiological embolisation of the uterine artery

warrants facilities and expertise in interventional

radiology, which may not be readily available in some obstetric units. In addition, in cases of

massive ongoing PPH, it may be difficult to transfer

patients to such radiological facilities. Infrequently,

complications such as ischaemia of the bladder and

uterus have also been reported.38 A systematic review

estimated a success (avoidance of hysterectomy) rate

of around 92% with uterine compression sutures,

91% after arterial embolisation, 84% after balloon

tamponade, and 85% after iliac artery ligation or

uterine devascularisation.6 Randomised controlled

trials of these treatment options would be difficult

to perform in such life-threatening emergencies.

To date, there is no good evidence to suggest that

one method is superior to another. As illustrated

in several of the cases in our series, the sequential

or concomitant use of these different interventions

may help to increase the success rate. The patient’s

condition, cause of the PPH, expertise of the surgeon,

and facilities available should all be considered when

choosing the most suitable treatment option.

Conclusion

In our experience, the use of compression sutures

for the management of massive PPH was effective

in preventing hysterectomy in around two thirds of

the cases. In this unselected cohort of patients with

severe PPH, our success rate appeared to be lower

than that reported in the literature. Other contingent

protocols should be available, should compression

sutures fail to control the haemorrhage. The

combined or sequential use of compression sutures

with other treatment modalities, such as balloon

tamponade, pelvic devascularisation or radiological

embolisation, may help to increase the success rate,

and should be explored further.

References

1. American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical

Management Guidelines for Obstetricians-Gynecologists. Number 76,

October 2006: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol

2006;108:1039-47.

2. Chandraharan E, Arulkumaran S.

Surgical aspects of postpartum haemorrhage. Best Pract Res Clin

Obstet Gynaecol 2008;22:1089-102. CrossRef

3. Condous GS, Arulkumaran S.

Medical and conservative surgical management of postpartum

hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2003;25:931-6.

4. B-Lynch C, Coker A, Lawal AH,

Abu J, Cowen MJ. The B-Lynch surgical technique for the control of

massive postpartum haemorrhage: an alternative to hysterectomy?

Five cases reported. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:372-5. CrossRef

5. Hayman RG, Arulkumaran S, Steer

PJ. Uterine compression sutures: surgical management of postpartum

hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:502-6. CrossRef

6. Doumouchtsis SK, Papageorghiou

AT, Arulkumaran S. Systematic review of conservative management of

postpartum hemorrhage: what to do when medical treatment fails.

Obstet Gynecol Surv 2007;62:540-7. CrossRef

7. Royal College of Obstetricians

and Gynaecologists. RCOG Green-top guideline No 52. Prevention and

management of postpartum haemorrhage; May 2009.

8. Varatharajan L, Chandraharan E,

Sutton J, Lowe V, Arulkumaran S. Outcome of management of massive

postpartum haemorrhage using the algorithm "HEMOSTASIS". Int J

Gynecol Obstet 2011;113:152-4. CrossRef

9. Knight M; UKOSS. Peripartum

hysterectomy in the UK: management and outcomes of the associated

haemorrhage. BJOG 2007;114:1380-7. CrossRef

10. Allam MS, B-Lynch C. The

B-Lynch and other uterine compression suture techniques. Int J

Gynaecol Obstet 2005;89:236-41. CrossRef

11. Arduini M, Epicoco G, Clerici

G, Bottaccioli E, Arena S, Affronti G. B-Lynch suture,

intrauterine balloon, and endouterine hemostatic suture for the

management of postpartum hemorrhage due to placenta previa

accreta. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2010;108:191-3. CrossRef

12. Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Uccella S,

Raio L, Bolis P, Surbek D. The Hayman technique: a simple method

to treat postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG 2007;114:362-5. CrossRef

13. Cho JH, Jun HS, Lee CN.

Hemostatic suturing technique for uterine bleeding during cesarean

delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:129-31. CrossRef

14. Hwu YM, Chen CP, Chen HS, Su

TH. Parallel vertical compression sutures: a technique to control

bleeding from placenta praevia or accreta during caesarean

section. BJOG 2005;112:1420-3. CrossRef

15. Bhal K, Bhal N. Mulik V,

Shankar L. The uterine compression suture—a valuable approach to

control major haemorrhage at lower segment caesarean section. J

Obstet Gynaecol 2005;25:10-4. CrossRef

16. Nelson WL, O'Brien JM. The

uterine sandwich for persistent uterine atony: combining the

B-Lynch compression suture and an intrauterine Bakri balloon. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 2007;196:e9-10. CrossRef

17. Pereira A, Nunes F, Pedroso S,

Saraiva J, Retto H, Meirinho M. Compressive uterine sutures to

treat postpartum bleeding secondary to uterine atony. Obstet

Gynecol 2005;106:569-72. CrossRef

18. Shazly SA, Badee AY, Ali MK.

The use of multiple 8 compression suturing as a novel procedure to

preserve fertility in patients with placenta accreta: case series.

Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 2012;52:395-9. CrossRef

19. Nanda S, Singhal SR. Hayman

uterine compression stitch for arresting atonic postpartum

hemorrhage: 5 years experience. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol

2011;50:179-81. CrossRef

20. Zheng J, Xiong X, Ma Q, Zhang

X, Li M. A new uterine compression suture for postpartum

haemorrhage with atony. BJOG 2011;118:370-4. CrossRef

21. Palacios-Jaraquemada JM.

Efficacy of surgical techniques to control obstetric haemorrhage:

analysis of 539 cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:1036-42. CrossRef

22. Schnarwyler B, Passweg D, von

Castelberg B. Successful treatment of drug refractory uterine

atony by fundal compression sutures [in German]. Geburtshilfe

Frauenheilkd 1996;56:151-3. CrossRef

23. Fotopoulou C, Dudenhausen JW.

Uterine compression sutures for preserving fertility in severe

postpartum haemorrhage: an overview 13 years after the first

description. J Obstet Gynaecol 2010;30:339-49. CrossRef

24. Makino S, Tanaka T, Yorifuji

T, Koshiishi T, Sugimura M, Takeda S. Double vertical compression

sutures: a novel conservative approach to managing post-partum

haemorrhage due to placenta praevia and atonic bleeding. Aust NZ J

Obstet Gynaecol 2012;52:290-2. CrossRef

25. B-Lynch C. Partial ischemic

necrosis of the uterus following a uterine brace compression

suture. BJOG 2005;112:126-7. CrossRef

26. Quahba J, Piketty M, Huel C,

et al. Uterine compression sutures for postpartum bleeding with

uterine atony. BJOG 2007;114:619-22. CrossRef

27. Mallappa Saroja CS, Nankani A,

El-Hamamy E. Uterine compression sutures, an update: review of

efficacy, safety and complications of B-Lynch suture and other

uterine compression techniques for postpartum haemorrhage. Arch

Gynecol Obstet 2010;281:581-8. CrossRef

28. Georgiou C. Balloon tamponade

in the management of postpartum haemorrhage: a review. BJOG

2009;116:748-57. CrossRef

29. Bakri YN, Amri A, Abdul Jabbar

F. Tamponade-balloon for obstetrical bleeding. Int J Gynaecol

Obstet 2001;74:139-42. CrossRef

30. Kong MC, To WW. Balloon

tamponade for postpartum haemorrhage: case series and literature

review. Hong Kong Med J 2013;19:484-90.

31. Treloar EJ, Anderson RS,

Andrews HS, Bailey JL. Uterine necrosis following B-Lynch suture

for primary postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG 2006;113:486-8. CrossRef

32. Joshi VM, Shrivastava M.

Partial ischemic necrosis of the uterus following a uterine brace

compression suture. BJOG 2004;111:279-80. CrossRef

33. Dadhwal V, Sumana G, Mittal S.

Hematometra following uterine compression sutures. Int J Gynaecol

Obstet 2007;99:255-6. CrossRef

34. Ochoa M, Allaire AD, Stitely

ML. Pyometria after hemostatic square suture technique. Obstet

Gynecol 2002;99:506-9. CrossRef

35. Wu HH, Yeh GP. Uterine cavity

synechiae after hemostatic square suturing technique. Obstet

Gynecol 2005;105:1176-8. CrossRef

36. O'Leary JA. Uterine artery

ligation in the control of postcesarean hemorrhage. J Reprod Med

1995;40:189-93.

37. Shin RK, Stecker MM, Imbesi

SG. Peripheral nerve ischaemia after internal iliac artery

ligation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;70:411-2. CrossRef

38. Porcu G, Roger V, Jacquier A,

et al. Uterus and bladder necrosis after uterine artery

embolisation for postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG 2005;112:122-3. CrossRef