Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Jun;25(3):228–34 | Epub 10 Jun 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE

Peanut allergy and oral immunotherapy

TH Lee, ScD, FRCP1; June KC Chan, MSc,

RD (US)1; PC Lau, RN, BNurs1; WP Luk, MPhil2;

LH Fung, MPhil2

1 Allergy Centre, Hong Kong Sanatorium

& Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

2 Medical Physics and Research, Hong

Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr TH Lee (takhong.lee@hksh.com)

Abstract

Peanut allergy is the commonest cause of

food-induced anaphylaxis in the world, and it can be fatal. There have

been many recent improvements to achieve safe methods of peanut

desensitisation, one of which is to use a combination of

anti–immunoglobulin E and oral immunotherapy. We have treated 27

patients with anti–immunoglobulin E and oral immunotherapy, and report

on the outcomes and incidence of adverse reactions encountered during

treatment. The dose of peanut protein tolerated increased from a median

baseline of 5 to 2000 mg after desensitisation, which is substantially

more than would be encountered through accidental ingestion. The

incidence of adverse reactions during the escalation phase of oral

immunotherapy was 1.8%, and that during the maintenance phase was 0.6%.

Most adverse reactions were mild; three episodes were severe enough to

warrant withdrawal from oral immunotherapy, but none required

epinephrine injection. Preliminary data suggest that unresponsiveness is

lost when daily ingestion of peanuts is stopped after the maintenance

period.

Introduction

Peanut is a leading food allergen alongside

shellfish, eggs, milk, beef, and tree nuts.1

Strict peanut avoidance is difficult and stressful for patients and

families. The incidence rates of accidental ingestion can be as high as

50%,2 3

and it can cause anaphylaxis, which is sometimes fatal. Therefore, new

management strategies for peanut allergy are required, such as oral

immunotherapy (OIT).

Peanut oral immunotherapy without anti–immunoglobulin E

Most trials on peanut OIT have been conducted in

the absence of anti–immunoglobulin E (anti-IgE) pretreatment.4 5 6 7 8 9 10 These studies involve gradually increasing small

doses of peanut (escalation phase) up to a maintenance dose of 300 to 4000

mg peanut protein (PP), with or without a phase of rush immunotherapy when

several doses were given on the same day at the start of OIT. The daily

maintenance dose was then sustained for 6 months to 3 years. Peanut

tolerance in subjects increased over time, and the tolerance to peanut in

open food challenge (OFC) at completion of the treatment was often more

than 2-fold greater than the daily maintenance intake. Efficacy of peanut

OIT was high, where 67 % to 93 % of subjects were successfully

desensitised to the maintenance dose. These studies have also been

considered to demonstrate an acceptable degree of safety although there

were dropouts in all the trials. Adverse reaction (AR) rates were 1.2% for

build-up doses and 3.7% to 6.3% for home doses. Most ARs were

oropharyngeal symptoms but there were some cases of anaphylaxis requiring

epinephrine injection. In addition, eosinophilic gastroenteritis was a

complication in some patients. In a recent peanut allergy OIT study using

defatted slightly roasted peanut flour for desensitisation, 4.3% of

children receiving peanut experienced severe ARs compared with <1% of

those receiving placebo; 21% of the peanut group withdrew from the study.10 Further, 14% of those ingesting

peanut required epinephrine injection, including one child who experienced

anaphylaxis and required three epinephrine injection, compared with 3.2%

on placebo.

To sustain non-responsiveness following OIT, Tang

et al7 used a combined therapy of

probiotics and peanut OIT. The majority (89.7%) of the probiotics and

peanut OIT group were desensitised, and sustained unresponsiveness (SU)

was achieved in 87.1% of the children, who could then consume peanuts ad

libitum. A related follow-up study indicated that 58% of the probiotics

and peanut OIT group subjects achieved 8-week SU at 4 years.8

Peanut oral immunotherapy with anti–immunoglobulin E

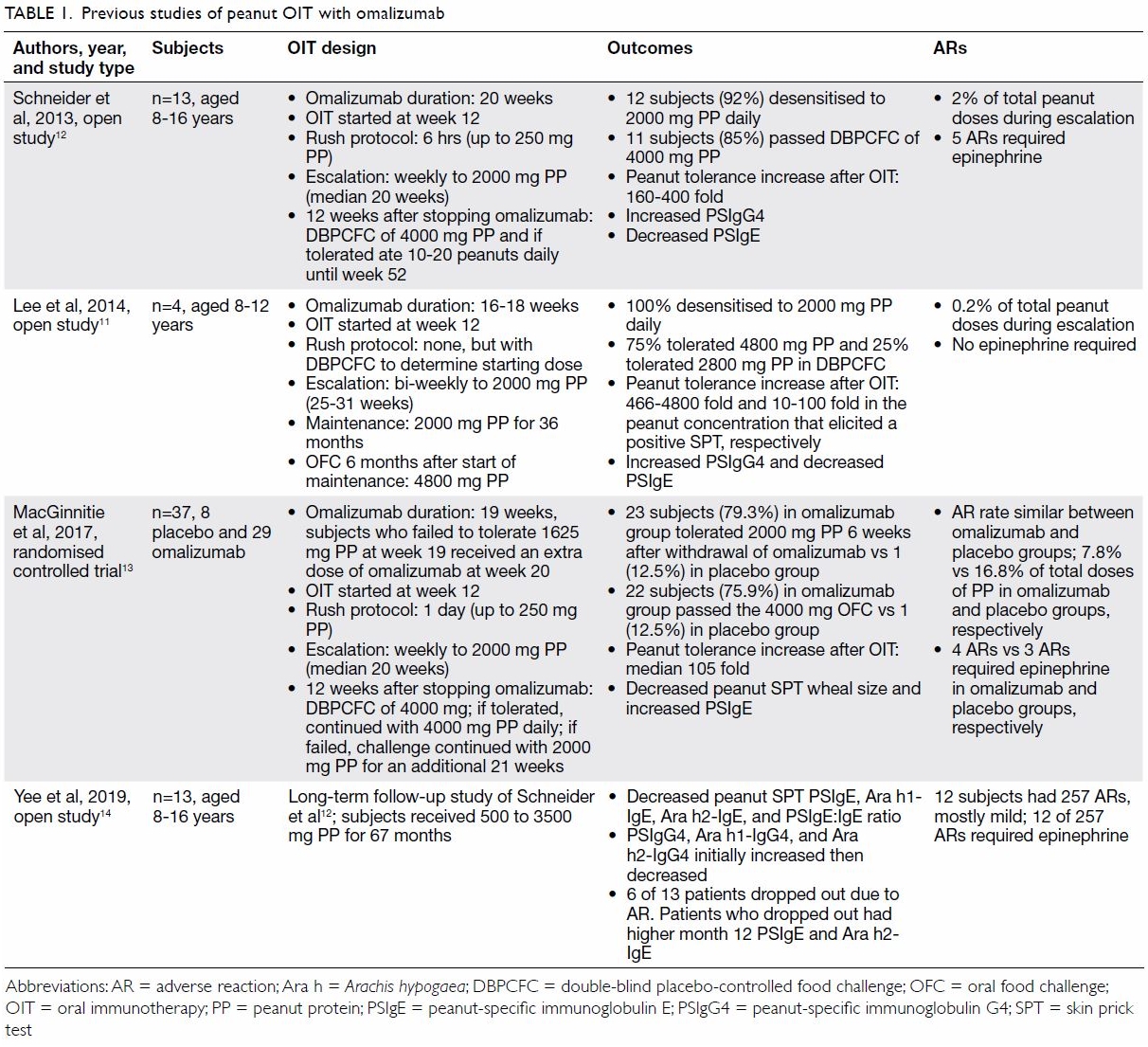

Prior studies that have combined anti-IgE

premedication with OIT are summarised in Table 1.11 12 13

14 In contrast to other studies, a

study conducted in Hong Kong by Lee et al11

did not have a rush immunotherapy phase (when several doses of peanuts

were administered on day 1); instead, peanut dose was increased more

gradually at 2-week intervals. Despite differences in study design, the

outcomes from all the studies were similar.11

12 13

14 Lee et al11 found four children tolerated 466 to 4800-fold more

PP on OFC than before OIT; their threshold in peanut-specific skin prick

tests increased by 10- to 100-fold; and each subject’s peanut

allergen-specific IgG4 level increased after OIT. The prevalence of ARs in

the study by Lee et al11 appeared

to be lower than that first reported by Schneider et al12 using anti-IgE combined with OIT which included a

rush immunotherapy step; however, the Hong Kong population included in the

Lee et al study was small.

Sublingual immunotherapy

Comparisons between studies on sublingual

immunotherapy (SLIT) are difficult because different doses and durations.15 16

17 18

19 However, tentative conclusions

can be drawn: in many instances SLIT achieved at least a 10-fold increase

in peanut tolerance from baseline after several years of treatment. The

ARs experienced during SLIT treatment were mild and consisted mainly of

oropharyngeal symptoms. Although SLIT had a better safety profile, OIT

appeared to be more efficacious overall.19

Epicutaneous immunotherapy

The early trials of epicutaneous immunotherapy

(EPIT) were encouraging with at least a 10-fold improvement in tolerated

dose following 8 weeks of treatment.20

21 The safety level was high. The

ARs were mostly local and mild and epinephrine injection was not required.

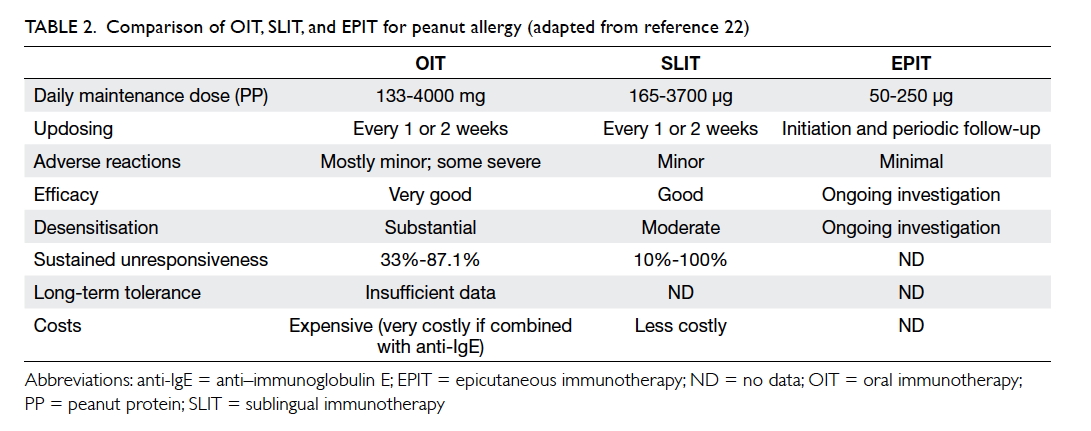

The efficacy, safety, and costs of OIT, SLIT, and

EPIT are compared in Table 2.22

Although it is more efficacious, OIT has greater potential for ARs and is

the most costly option, especially if combined with anti-IgE treatment.

Update on the Hong Kong experience

Our centre has now treated 27 peanut-allergic

patients aged 6 to 16 years (22 male, 5 female) with anti-IgE and OIT,

including the four children previously reported.11

Patients were considered for anti-IgE and OIT treatment if they were: aged

≥6 years with a history of allergic symptoms developing within 60 minutes

of peanut ingestion; serum total IgE between 30 and 1500 IU/mL; a positive

skin prick test and/or presence of peanut-specific IgE, and positive oral

peanut challenge. They were of good general health with no prior exposure

to monoclonal antibodies. Asthma must have been under control, with a

forced expiratory volume in 1 second of at least 80% of the predicted

value. Systemic glucocorticoids, beta blockers, and angiotensin-converting

enzyme inhibitors were prohibited before screening and throughout the

study. Aspirin, antihistamines, and antidepressants were not permitted for

3 days, 1 week, and 2 weeks, respectively, before skin testing or oral

food challenge. If potential subjects had poorly controlled asthma, poorly

controlled atopic dermatitis, or inability to discontinue antihistamines

or other medication for skin testing and oral challenges, they were

excluded. They were also ineligible if it seemed unlikely that they would

comply with the treatment protocol.

The subjects received between 150 and 600 (median

375) mg of anti-IgE for a median of 18 weeks, as determined by baseline

serum IgE concentration and body weight.11

From about 12 weeks after beginning anti-IgE pretreatment, peanuts were

eaten daily at home at an initial dose determined by OFC according to our

previously reported protocol.11

Updosing was supervised at bi-weekly intervals in the clinic for 12 to 28

(median 16) weeks (escalation phase) until an oral intake of 2000 mg PP

daily was achieved, as previously described in detail.11 The parents of one child requested to stop escalation

after 800 mg of PP because they felt that he was already protected from

accidental ingestion and had a strong taste aversion to peanuts. He

continued on 800 mg during his maintenance phase. If a patient had a major

AR on an updosing visit, the next daily dose was reduced to a previously

tolerated dose (often halved), and escalation proceeded more slowly (3-4

weeks) until higher doses were tolerated or the patient withdrew.

Successful escalation was followed by a maintenance phase, when patients

normally ingested 2000 mg PP daily.

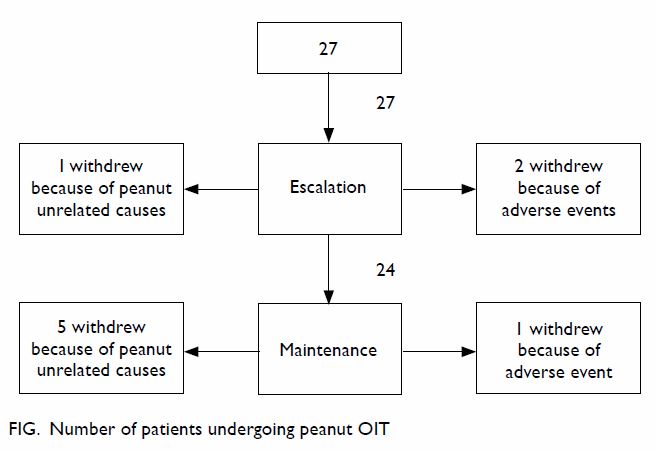

Twenty-three of the 27 peanut allergic children

completed the escalation phase according to protocol (85%). There were

three dropouts, of which two were caused by peanut-related AR, and the

third moved away from Hong Kong for family reasons. Another child stopped

updosing at 800 mg, as described already, but continued into the

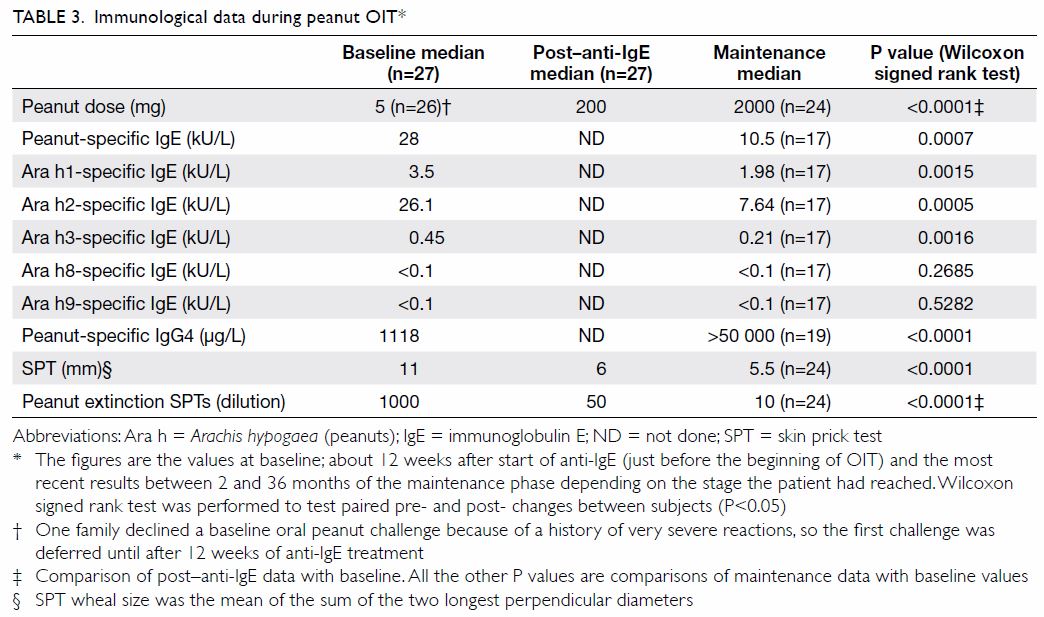

maintenance phase (Fig). The dose of PP tolerated at OFC increased from

a median of 5 mg at baseline to 200 mg after anti-IgE treatment and

subsequently to a median of 2000 mg in the maintenance phase. There was a

400-fold improvement in the median tolerated peanut dose (Table

3), yielding a final tolerance greater than the amount of peanuts

likely to be encountered through inadvertent ingestion.

The immunological data are shown in Table

3. There was a marked decrease in biomarkers such as peanut-specific

IgE and Ara h1, 2, and 3 (but not in Ara h 8 and 9, which were very low at

baseline). Skin prick testing (SPT) and the dilution of peanut extract in

extinction titration SPT also showed improvements. The level of peanut

sIgG4 increased substantially, consistent with the recruitment of an

IL-10/Treg pathway.

Side-effects during peanut oral immunotherapy

Escalation phase

The ARs during updosing in hospital were directly

observed; those ARs experienced at home were self-reported by patients’

parents. There were 18 observed and 46 reported episodes of AR to 3560

administered doses of peanut (1.8%). Thus, 71.9% of all ARs during the

escalation phase occurred at home. One episode could comprise one or more

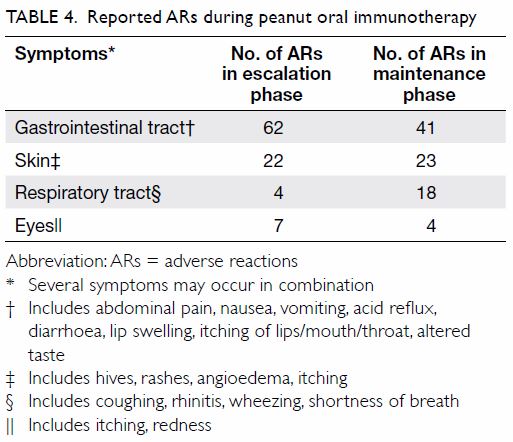

symptoms (Table 4). Most ARs were minor (Table

4) and resolved spontaneously or after administration of an

antihistamine. One subject had 12 minor episodes but still completed

escalation. There were four major episodes, which involved development of

asthma, repeated vomiting, and angioedema (0.1%), and they occurred in two

patients who dropped out (Fig).

The frequent occurrence of

gastrointestinal symptoms (n=62) is consistent with that reported previously.14 23

Maintenance phase

Twenty-four patients entered the maintenance phase

of OIT (Fig). The duration of their maintenance phases so

far has ranged from 2 to 42 (median 24) months. One child planned to study

overseas and therefore continued on the maintenance doses for 6 months

longer than planned (42 months in total) until he returned to Hong Kong

for holidays. All parents and patients were asked to report any AR.

To date, there have been 80 reported episodes of AR

from 14 350 administered doses (0.6%). The majority of subjects had no

ARs, and 85% of all the ARs reported were experienced by seven (29.2%)

patients. Six of these patients were able to continue with OIT, but one

patient withdrew because of severe eczema.

Forty-one, 23, and 18 side-effects reported during

the maintenance phase were related to the gastrointestinal tract, skin,

and respiratory system, respectively; thus, gastrointestinal symptoms

predominated again (Table 4). The gastrointestinal symptoms were mostly

mild and resolved either spontaneously or after antihistamine

administration. Occasionally, it was also necessary to administer an oral

anti-spasmodic drug.

While the incidence of AR during the maintenance

phase of OIT was very low, repeated ARs still occurred in some subjects,

and one episode was severe enough to warrant withdrawal from the

programme. This highlights the importance of continued vigilance

throughout OIT.

Dropouts

Four patients left Hong Kong for family reasons.

Another two patients (twins) developed unexplained intermittent mild

neutropenia after 2 years of maintenance OIT, which was not caused by

peanuts. Nonetheless, although they stopped daily peanut consumption, they

continued to be monitored to assess for SU. Two children were withdrawn

during escalation, and one dropped out during maintenance because of

peanut allergy related to AR during OIT (Fig). Thus, overall, one-third of subjects dropped

out (9 of 27), but only one-third of the dropouts (3 patients; 11.1%)

withdrew because of AR caused by peanut ingestion.

The incidence of AR in our subjects was similar5 9 24 or even lower than that in previous reports.6 8 10 25 26 Baseline allergic rhinitis and peanut SPT wheal sizes

have been suggested to be significant predictors of higher overall rate of

AR during peanut OIT,23 but in our

series, baseline peanut SPT results; extinction dilution SPTs;

peanut-specific IgE; Arachis hypogaea 1-, 2-, 3-, 8-, and

9-specific IgE concentrations; and the presence of rhinitis and asthma

were not predictors of ARs (P>0.05 for all correlations).

Preliminary data on sustained unresponsiveness

A major concern regarding immunotherapy is whether

it can induce long-term tolerance. Seven of our patients have been

followed up after cessation of daily peanut consumption. Three of these

subjects discontinued peanut ingestion after maintenance treatment with

1600 to 2000 mg PP daily, and their sensitivity returned, as evidenced by

ARs to intentional or accidental ingestion of peanuts as well as ARs to

100 mg and 400 mg PP upon OFC at 6 months (n=2) and 12 months (n=1),

respectively. The other four subjects have continued to ingest their

maintenance doses of peanuts 3 times weekly after the maintenance phase

was completed and have not experienced any ARs after 4, 7, 8, and 24

months of observation, respectively.

Syed et al27

randomised 43 subjects aged 4 to 45 years to receive peanut OIT (n=23) or

placebo (n=20). Peanut doses were escalated to 4000 mg PP and maintained

for 24 months. Then, subjects avoided peanuts for 3 months, and their SU

was assessed. In all, 87% of the subjects were successfully desensitised

to 4000 mg PP, and 30% achieved SU after avoiding peanuts for 3 months. Of

the seven subjects who had SU at 3 months, only three of them (13% of the

treatment group) still achieved SU at 6 months of peanut avoidance.

Conclusions

Our protocol of combining anti-IgE with OIT is

efficacious and safe, with only minor side-effects encountered by most

patients. This is a retrospective record review and therefore is an audit

of our real-world experience. There is growing momentum behind the

development of commercial products for peanut desensitisation,9 10 21 and it is essential to compare their efficacy and

safety with existing techniques for peanut immunotherapy in a real-world

situation.28 29 30

Selection of suitable patients to undergo OIT is

critical, as it is a labour-intensive and expensive treatment that

requires time, patience, and compliance from everyone involved. We spend

much time explaining the procedure in detail to the family and child to

ascertain whether they are likely to complete the treatment. The patient

or the patient’s parent (if the patient is a child) signs an informed

consent form if they agree to proceed. If they have concomitant asthma, we

ensure that this is optimally controlled before embarking on OIT. Even

with careful selection, four of our subjects left Hong Kong for family

reasons before OIT was completed. This was unavoidable but nevertheless

undesirable for the continuity of their treatment. Any treatment that

takes years to complete will always be a challenge, especially for

families whose children relocate for study, work, or other reasons. While

some treatments can be continued by centres overseas, OIT expertise is not

so easily accessible, and it may be necessary to discontinue treatment.

This is regrettable, as all the parents and patients, who completed their

desensitisation programmes successfully reported that their quality of

life had been improved.

We recommend that this treatment only be offered by

specialists with the appropriate training within an environment with

immediate resuscitation facilities and support staff who are trained to

manage allergic emergencies and can undertake patient education.

Our experience suggests that peanut sensitivity

will likely return after a few months when OIT is stopped, so regular

ingestion of peanut consumption is required to sustain the desensitised

state. We now advise patients to continue consuming the maintenance dose

of peanuts at least 3 times weekly to sustain desensitisation. They are

seen every 6 months for skin testing, and they undergo a formal peanut

challenge annually or more frequently, according to clinical judgment. We

also advise that they retain their epinephrine autoinjectors for emergency

treatment of unexpected events.

Alternative methods that hold promise for peanut

desensitisation are being developed, including SLIT,15 16 17 18 20 low-dose OIT without anti-IgE,6 9 31 co-administration of a probiotic7 8 with OIT to

promote longer-term tolerance, and EPIT.21

Thus additional transformative treatments for peanut and other food

allergies will be forthcoming in the near future.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design, acquisition

of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript,

and critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors also

had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final

version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Hong Kong Sanatorium

& Hospital Research Committee (Ref RC-2018-27). Patients provided

informed consent.

References

1. Ho MH, Lee SL, Wong WH, Ip P, Lau YL.

Prevalence of self-reported food allergy in Hong Kong children and teens—a

population survey. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2012;30:275-84.

2. Michelsen-Huisman AD, van Os-Medendorp

H, Blom WM, et al. Accidental allergic reactions in food allergy: causes

related to products and patient’s management. Allergy 2018;73:2377-81. Crossref

3. Sicherer SH, Burks AW, Sampson HA.

Clinical features of acute allergic reactions to peanut and tree nuts in

children. Pediatrics 1998;102:e6. Crossref

4. Jones SM, Pons L, Roberts JL, et al.

Clinical efficacy and immune regulation with peanut oral immunotherapy. J

Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124:292-300. Crossref

5. Varshney P, Jones SM, Scurlock AM, et

al. A randomized controlled study of peanut oral immunotherapy: clinical

desensitization and modulation of the allergic response. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 2011;127:654-60. Crossref

6. Anagnostou K, Islam S, King Y, et al.

Assessing the efficacy of oral immunotherapy for the desensitisation of

peanut allergy in children (STOP II): a phase 2 randomised controlled

trial. Lancet 2014;383:1297-304. Crossref

7. Tang ML, Ponsonby AL, Orsini F, et al.

Administration of a probiotic with peanut oral immunotherapy: a randomized

trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:737-44.e8. Crossref

8. Hsiao KC, Ponsonby AL, Axelrad C, Pitkin

S, Tang ML, PPOIT Study Team. Long-term clinical and immunological effects

of probiotic and peanut oral immunotherapy after treatment cessation:

4-year follow-up of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2017;1:97-105. Crossref

9. PALISADE Group of Clinical

Investigators, Vickery BP, Vereda A, et al. AR101 oral immunotherapy for

peanut allergy. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1991-2001. Crossref

10. Bird JA, Spergel JM, Jones SM, et al.

Efficacy and safety of AR101 in oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy:

results of ARC001, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2

clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:476-85.e3.

11. Lee TH, Chan J, Lau VW, Lee WL, Lau

PC, Lo MH. Immunotherapy for peanut allergy. Hong Kong Med J

2014;20:325-30. Crossref

12. Schneider LC, Rachid R, LeBovidge J,

Blood E, Mittal M, Umetsu DT. A pilot study of omalizumab to facilitate

rapid oral desensitization in high-risk peanut-allergic patients. J

Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;132:1368-74. Crossref

13. MacGinnitie AJ, Rachid R, Gragg H, et

al. Omalizumab facilitates rapid oral desensitization for peanut allergy.

J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139:873-81. Crossref

14. Yee CS, Albuhairi S, Noh E, et al.

Long-term outcome of peanut oral immunotherapy facilitated initially by

omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:451-61.e7. Crossref

15. Kim EH, Bird JA, Kulis M, et al.

Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy: clinical and immunologic

evidence of desensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:640-6.e1. Crossref

16. Fleischer DM, Burks AW, Vickery BP, et

al. Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy: a randomized,

double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol

2013;131:119-27.e1-7. Crossref

17. Burks AW, Wood RA, Jones SM, et al.

Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy: long-term follow-up of a

randomized multicenter trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:1240-8.e1-3.

Crossref

18. Narisety SD, Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA,

Keet CA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study

of sublingual versus oral immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut

allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:1275-82.e1-6. Crossref

19. Pajno GB, Fernandez-Rivas M, Arasi S,

et al. EAACI Guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: IgE-mediated food

allergy. Allergy 2018;73:799-815. Crossref

20. Sindher S, Fleischer DM, Spergel JM.

Advances in the treatment of food allergy: sublingual and epicutaneous

immunotherapy. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2016;36:39-54. Crossref

21. Jones SM, Sicherer SH, Burks AW, et

al. Epicutaneous immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut allergy in

children and young adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139:1242-52. Crossref

22. Parrish CP. Management of peanut

allergy: a focus on novel immunotherapies. Available from:

https://www.ajmc.com/journals/supplement/2018/managed-care-perspective-peanut-allergy/management-of-peanut-allergy-a-focus-on-novel-immunotherapies.

Accessed 15 Feb 2019.

23. Virkud YV, Burks AW, Steele PH, et al.

Novel baseline predictors of allergic side effects during peanut oral

immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139:882-8.e5. Crossref

24. Vickery BP, Berglund JP, Burk CM, et

al. Early oral immunotherapy in peanut-allergic preschool children is safe

and highly effective. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139:173-81.e8. Crossref

25. Blumchen K, Ulbricht H, Staden U, et

al. Oral peanut immunotherapy in children with peanut anaphylaxis. J

Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:83-91.e1. Crossref

26. Yu GP, Weldon B, Neale-May S, Nadeau

KC. The safety of peanut oral immunotherapy in peanut-allergic subjects in

a single-center trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2012;159:179-82. Crossref

27. Syed A, Garcia M, Lyu SC, et al.

Peanut oral immunotherapy results in increased antigen-induced regulatory

T-cell function and hypomethylation of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3). J

Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:500-10. Crossref

28. Wasserman RL, Hague AR, Pence DM, et

al. Real-world experience with peanut oral immunotherapy: lessons learned

from 270 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:418-26.e4. Crossref

29. Couzin-Franke J. A revolutionary

treatment for allergies to peanuts and other foods is going mainstream—but

do the benefits outweigh the risks? Available from: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/10/revolutionary-treatment-allergies-peanuts-and-other-foods-going-mainstream-do-benefits. Accessed 16 May

2019.

30. Wasserman RL, Jones DH, Windom HH.

Oral immunotherapy for food allergy: The FAST perspective. Ann Allergy

Asthma Immunol 2018;121:272-5. Crossref

31. Nagakura KI, Yanagida N, Sato S, et

al. Low-dose oral immunotherapy for children with anaphylactic peanut

allergy in Japan. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2018;29:512-8. Crossref