Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Jun;25(3):201–8 | Epub 29 May 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Budget impact of introducing tofacitinib to the public

hospital formulary in Hong Kong, 2017-2021

X Li, PhD1; Swathi Pathadka, PharmD1;

Kenneth K Man, BSc, MPH2; Ian CK Wong, PhD1,2;

Esther WY Chan, PhD1

1 Department of Pharmacology and

Pharmacy, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 School of Pharmacy, University College

London, London, United Kingdom

Corresponding author: Dr Esther WY Chan (ewchan@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: As the first

approved oral kinase inhibitor, tofacitinib is effective and

well-tolerated, but more expensive than conventional treatments for

uncontrolled rheumatoid arthritis. Public formulary listing typically

exerts a positive impact on the uptake of new drugs. We aimed to assess

the budgetary impact of introducing tofacitinib into the Hospital

Authority Drug Formulary as a fully subsidised drug in Hong Kong.

Methods: We applied a

population-based budget impact model to trace the number of eligible

patients receiving biologics or tofacitinib treatment, then estimated

the 5-year healthcare expenditure on rheumatoid arthritis treatments,

with or without tofacitinib (2017-2021). We used linear regression to

estimate the number of target patients and compound annual growth rate

to estimate market share. Competing treatments included abatacept,

adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, and

tofacitinib. Retail price was used for drug costs, valued in Hong Kong

dollars (HK$) in 2017 and discounted at 4% per year.

Results: The annual treatment

cost of tofacitinib was HK$74 214 per patient, and the costs of

biologics ranged from HK$64 350 to HK$115 700. Without tofacitinib, the

annual government health expenditures for rheumatoid arthritis treatment

were estimated to increase from HK$147.9 million (2017) to HK$190.6

million (2021). The introduction of tofacitinib to the formulary would

reduce healthcare expenditures by 17.3% to 20.3% per year, with

cumulative savings of HK$192.8 million; this change was estimated to

provide consistent savings (HK$66.4 million to HK$196.8 million) in all

tested scenarios.

Conclusion: Introduction of

tofacitinib to the formulary will provide 5-year savings, given the

current drug price and patient volume.

New knowledge added by this study

- Government healthcare expenditures for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis were estimated to be lowered by approximately 20% upon the introduction of tofacitinib.

- The cost-saving impact of introducing tofacitinib to the Hospital Authority Drug Formulary is determined by interactions between drug prices and market shares of novel disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

- Based on current drug prices and patient volume, introduction of tofacitinib to the Hospital Authority Drug Formulary will lower healthcare expenditures for at least 5 years.

- Tofacitinib will offer an orally administered option for patients who showed poor response to initial therapy and will intensify market competition for DMARDs.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic connective

tissue autoimmune disorder that leads to considerable functional

disability, reduced quality of life, and loss of earning capacity1 Conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic

drugs (csDMARDs), such as methotrexate, have long been regarded as the

standard of care for RA and are widely used in newly diagnosed patients to

slow disease progression, control disease manifestations, and achieve

remission.2 3 However, csDMARDs exhibit relatively slow onset of

action and require close monitoring due to the potential for adverse

events, especially in patients with chronic co-morbidities.2 4 For patients

who exhibit poor prognostic factors with moderate to high disease activity

after initial therapy with csDMARDs, novel biologic DMARDs (eg,

infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, or golimumab) or targeted

synthetic, small-molecule DMARDs (eg, tofacitinib) are recommended for use

in combination with csDMARDs, or as monotherapy.2

3 5

Tofacitinib is a small synthetic molecule Janus

kinase inhibitor which modulates leukocyte recruitment, activation, and

effector cell function at sites of inflammation. It is the first orally

bioavailable therapeutic agent to improve clinical remission in patients

with RA.6 The safety and efficacy

of tofacitinib, relative to those of csDMARDs, have been reported in

recent landmark trials and observational studies. Tofacitinib monotherapy

was superior to methotrexate for reduction of RA symptoms and inhibition

of the progression of structural joint damage in patients who had not

previously received methotrexate or therapeutic doses of methotrexate.7 In patients with inadequate responses to methotrexate,

tofacitinib was non-inferior to adalimumab for symptom control when used

as a combination therapy with methotrexate.8

However, the increased risk of adverse events associated with tofacitinib,

including infections (eg, herpes zoster and tuberculosis) and malignancy,

is a major limitation that requires long-term surveillance and careful

prescribing practices.7 8

Similar to biologic DMARDs, tofacitinib is more

expensive than csDMARDs (eg, methotrexate $1 versus tofacitinib $66 per

tablet in the US9). Several studies have supported the cost-effectiveness

of tofacitinib. When used as an alternative first-line treatment to

csDMARD, tofacitinib was found to be cost-effective in the South Korean

population due to its ability to significantly improve patients’ quality

of life.10 When used in

combination with a csDMARD, a study in the US showed that tofacitinib was

highly cost-effective in patients with severe RA, relative to combinations

of most biologics with csDMARD.11

In a recent modelling study, tofacitinib was also found to be cost-saving

as a second-line therapy following methotrexate failure and as a

third-line therapy following the failure of a biologic therapy.12

Treatment decisions for patients with uncontrolled

RA are increasingly complex because there are no direct head-to-head

comparisons among novel DMARDs from landmark trials, and there are limited

long-term data describing medication safety and compliance. Selection of

biologic DMARDs or tofacitinib is largely dependent on multiple clinical

and socio-economic factors, including disease activity, progression of

structural damage, and co-morbidities within a particular patient, as well

as their preferences for route of administration and dosing frequency, and

the regulatory and cost barriers to drug access.13

Tofacitinib was approved in Hong Kong as a

prescription-only drug in 2014.14

At the time of writing, tofacitinib is listed as a self-financed item

without safety net in the public hospital formulary; thus, the cost of

tofacitinib is entirely out-of-pocket for patients.15 The impact of funding tofacitinib in the public

healthcare system remains unknown. In the present study, we assessed the

budgetary impact of introducing tofacitinib into the Drug Formulary of the

Hospital Authority—the statutory body that manages Hong Kong’s public

hospital services. The objective of this study was to provide guidance for

drug listing decisions from a public institutional perspective.

Methods

Target population

The target population comprised adults with RA who

showed inadequate response to initial csDMARD monotherapy and were

recommended for treatment with novel DMARDs.2

5 Adult patients who had been

treated with novel DMARDs, during the period from 1 January 2009 to 31

December 2015, were identified from the Clinical Data Analysis and

Reporting System (CDARS) of Hong Kong (a territory-wide electronic health

record). Developed by the Hospital Authority, a statutory body that

manages all public hospitals and provides health service to all Hong Kong

residents (over 7 million),16

CDARS is recognised as a unique population-based electronic health record

in Hong Kong that enables publication of an increasing number of

high-quality studies.17 18 19 20 21 A

detailed description of CDARS can be found elsewhere.22 23 24 In this study, retrieved data from the electronic

patient records included demographics, date of registered death, date of

hospital admission and discharge, drug dispensing records and diagnoses.

Patient records from CDARS are de-identified and linked with unique

reference keys to protect patient privacy and facilitate data retrieval.

Based on the eligible patients identified from CDARS, the number of

patients on novel DMARDs was calculated annually between the year of 2009

and 2015 and projected for the years from 2017 to 2021 assuming a linear

trend of increasing in patients receiving novel DMARDs (online

supplementary Appendix 1).

Budget impact model

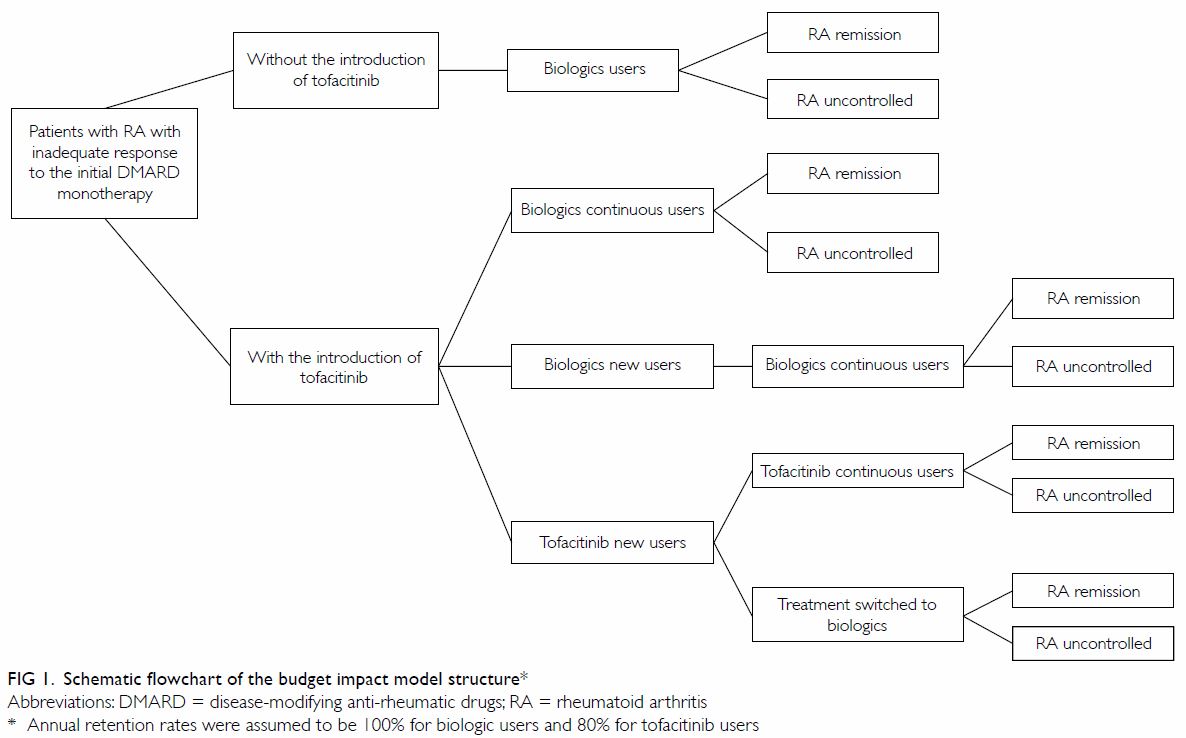

We developed a population-based budget impact model

to trace the number of patients with RA on novel DMARDs and assess changes

in healthcare expenditures with respect to RA treatments (Fig

1). The model used a cohort of patients diagnosed with RA who showed

inadequate responses to initial DMARD therapy. Without the introduction of

tofacitinib, patients were assumed to use one of the biologic DMARDs

(monotherapy or combination therapy with a csDMARD), according to its

corresponding market share. The introduction of tofacitinib provided an

additional option to patients newly placed on novel DMARDs, with treatment

choices determined by projected market share. We assumed that the annual

retention rate of biologics was 100%, whereas that of tofacitinib was 80%,

in accordance with landmark trial results.7

Dropout patients were assumed to switch to one of the biologics, according

to its corresponding market share in the same year. We also assumed that

the safety and efficacy profiles of biologics and tofacitinib were

equivalent, based on a recent Cochrane review that assessed novel DMARDs

compared to placebo or standard care,25

and based on a head-to-head comparison between tofacitinib and adalimumab.8 The assumptions of the projection

model are summarised in online supplementary Appendix 2.

The analysis was conducted from the public

institutional perspective of Hong Kong, and direct medical costs were

calculated. The numbers of patients on each treatment and overall

medication costs were calculated on a yearly basis, and results were

cumulative over a period of 5 years (2017-2021). Monetary value was

expressed in Hong Kong dollars (HK$) in 2017, discounted at 4% per year.26 27

The study outcome was the difference in healthcare expenditures with

respect to RA treatment, with or without introducing tofacitinib into the

formulary. There was no pre-defined threshold for a favourable budget

impact.

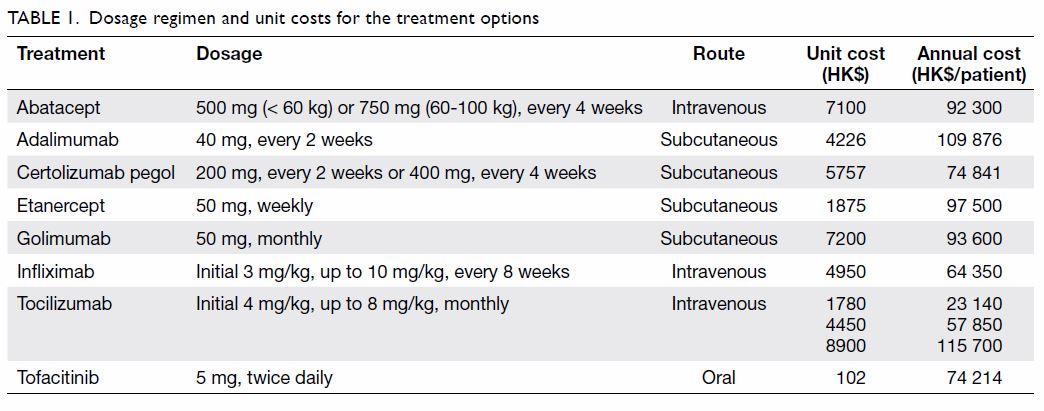

Competing alternatives and market shares

Treatment options were assumed to include biologics

(eg, abatacept, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab,

infliximab, and tocilizumab) and tofacitinib, using current

recommendations for patients with inadequate responses to csDMARDs. Table

1 shows dosage regimens, per dose cost in local currency, and annual

medication costs for each treatment. The number of patients on each

treatment was determined by the corresponding market share of the

treatment and the total number of eligible patients in the same year.

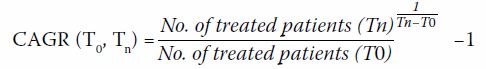

Based on the number of biologics that were prescribed from 2013 to 2015

(as recorded in CDARS), the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) was

estimated by following equation28:

We assumed a constant CAGR for each biologic; the

corresponding market share was projected yearly between 2017 and 2021

(online supplementary Appendix 3). The overall market share of novel

DMARDs was assumed to be 100%.

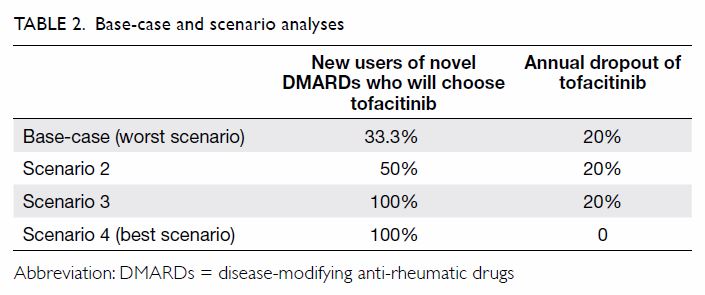

Base-case and scenario analyses

In the base-case analysis, we assumed that

one-third of the eligible patients who were new users of novel DMARDs

would be placed on tofacitinib in the first year. In accordance with the

findings of the landmark trial, 20% of tofacitinib users were expected to

drop out each year, due to adverse events.7

We assumed that the dropout patients would choose one of the biologics and

that the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib and all biologics were

equivalent; hence, the switch would only affect medication costs. Three

scenario analyses were conducted to assess the impact of uncertainties on

the base-case conclusion: specifically, uncertainties were considered in

market share of tofacitinib and dropout of tofacitinib users (Table

2). The base-case scenario was regarded as the worst scenario for

the uptake of tofacitinib (market share of 33.3% among new novel DMARDs

users and 20% annual dropout). In the other three scenarios, the

first-year uptake of tofacitinib increased from 50% to 100%, and the

annual dropout rate ranged from 0% to 20%. Scenario 4 was determined to be

the best scenario, with the highest first-year uptake and 100% retention

over 5 years. We also tested the impact of discounting (0-4%) on base-case

results, as there are no health technology assessment guidelines with

respect to the proper discount rate for Hong Kong.

Statistical Analysis System software (version 9.4,

SAS Inc, Cary [NC], US) was used for data manipulation and analysis.

Microsoft Excel (2003 for Windows; Microsoft Corp, Redmond [WA], US) was

used to establish the budget impact model and generate corresponding

plots.

Ethics

The study was designed and reported in accordance

with the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards

Statement.29 The study protocol in

which CDARS was used to estimate the number of eligible patients was

approved by the Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster and The

University of Hong Kong Institutional Review Board (UW14-602). Ethics

approval for the budget impact analysis was waived, as it comprised a

statistical modelling projection without patient contact.

Results

Base-case analysis

Between 2017 and 2021, the estimated number of

eligible patients on novel DMARDs increased from 1466 to 2375. Without

introducing tofacitinib into the formulary, the annual government health

expenditures for RA treatment were projected to increase from HK$147.9

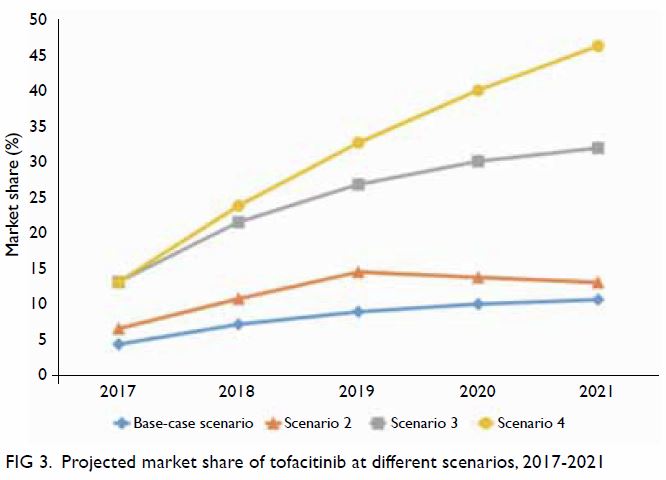

million (2017) to HK$190.6 million (2021) [Fig 2a]. The increased expenditures were driven by

increased patient volume and growth of the biologics market. Addition of

tofacitinib to the formulary would reduce relevant healthcare expenditures

by HK$33.1 million to HK$39.9 million annually (17.3% to 20.3% reduction)

[Fig 2a]. Budgetary savings were expected, regardless

of discount rates (Fig 2). Cumulative savings over the 5-year study

period were projected to be HK$192.8 million (discounted at 4%) and

HK$208.8 million (undiscounted), respectively.

Figure 2. Projected healthcare expenditure on rheumatoid arthritis treatment, 2017-2021, showing (a) discounted costs and (b) undiscounted costs

Scenario analyses

Variations in the market share of tofacitinib were

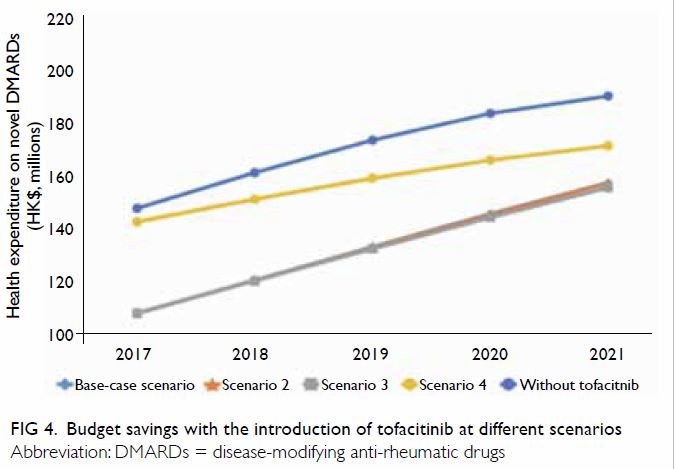

assessed in different test scenarios (Fig 3). The base-case scenario assumed the most

conservative uptake of tofacitinib, comprising 4.4% to 10.7% of the

overall novel DMARD market. With the assumption that half of the new users

of novel DMARDs would choose tofacitinib, combined with the assumption of

an annual dropout rate of 20% (Scenario 2), the market share of

tofacitinib was expected to increase from 6.6% to 13.1% over the 5-year

study period. With the assumption that all new users of novel DMARDs would

choose tofacitinib (Scenario 3), the market share was expected to increase

from 13.2% to 32% over the 5-year study period. In the best-case scenario

(Scenario 4), 100% uptake was assumed, combined with the assumption of an

annual dropout rate of 0% among new users, the market share of tofacitinib

was expected to increase linearly from 13.2% in 2017 to 46% in 2021.

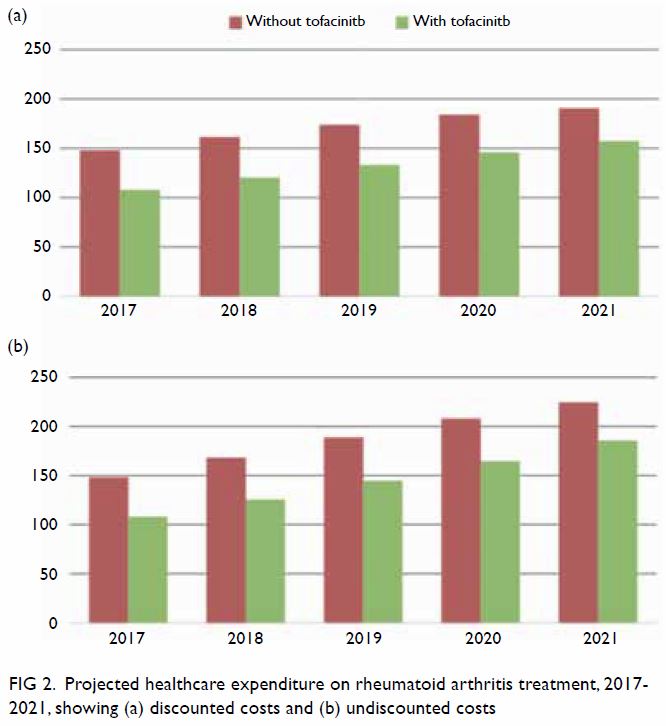

The estimated annual health expenditures for RA

treatments were positively correlated with the uptake of tofacitinib. In

all tested scenarios, the introduction of tofacitinib to the public

hospital formulary provided consistent savings, compared to the current

situation where tofacitinib is self-financed (Fig 4). Similar to the base-case scenario, the

cumulative budget savings over the 5-year study period were estimated to

be HK$193.5 million and HK$196.8 million for Scenarios 2 and 3. In the

best-case scenario with the highest uptake of tofacitinib, the total

savings were reduced to HK$66.4 million (Fig 4).

Discussion

In Hong Kong, patients with uncontrolled RA must

pay HK$20 000 to HK$100 000 per year out-of-pocket to receive novel DMARDs

treatments that facilitate disease remission. In addition to the

progressive loss of working ability associated with RA, the high cost of

therapy poses an additional burden to affected patients, their families,

and society.30 In the present

study, we attempted to provide guidance with respect to introduction of

tofacitinib to the public hospital formulary by analysing the budgetary

impact of this change. Drug listing and subsidy decisions rely on the

principles of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness; thus, they must

consider a variety of factors, including clinical evidence and impact on

healthcare costs.31 Budgetary

impact is a key element of health economic evaluations that must be

determined before formulary approval in many developed countries with

established health technology assessments.32

33 34

Local and international health economists have suggested that systematic

procedures and transparency are needed with respect to formulary

decision-making in Hong Kong.35

Based on the current drug costs of novel DMARDs and the volume of patients

who receive treatment in public hospitals in Hong Kong, our model

projection suggests that the introduction of tofacitinib would provide

savings over the 5-year study period.

In our analysis, governmental healthcare

expenditures for RA treatments were lowered by approximately 20% upon the

introduction of tofacitinib to the public hospital formulary. With the

assumption that none of the novel DMARDs were discontinued or withdrawn

from the market, the annual treatment costs of tofacitinib were lower than

those of all biologics, except infliximab. This may explain the increased

market share of tofacitinib, as well as the reduction in overall RA

treatment costs. In clinical practice, both biologic DMARDs and

tofacitinib are commonly used in combination with a csDMARD.2 3 In our

analysis, we did not consider the cost of csDMARDs, as they are currently

listed as fully subsided drugs in the formulary and are thus expected to

have minimal impact on the cost of RA treatment, regardless of the

addition of tofacitinib to the formulary.

The introduction of tofacitinib to the formulary

will intensify market competition, which may improve the effectiveness of

disease management36; moreover, this change will provide a more convenient

orally administered option for patients who are reluctant to undergo

subcutaneous or intravenous injections, and who are willing to switch from

biologic DMARDs to an alternative therapy.37

38 Patient preferences regarding

RA treatment may affect compliance, adherence, and quality of life.39 40 The route

of administration significantly influences the decision between

tofacitinib and biologics.41 Among

all factors that impact patients’ therapeutic preferences, the convenience

of oral administration has been shown to exhibit the strongest influence.39 Thus, the oral route of

administration for tofacitinib is likely to provide an advantage over the

parenteral route of administration for biologics.

Given current evidence regarding the

cost-effectiveness of tofacitinib, broader utilisation of tofacitinib can

be expected in the future if safety concerns are appropriately addressed.

The underlying effector mechanism of tofacitinib comprises intracellular

transduction inhibition, which carries the potential for interaction with

the immune system; these factors may contribute to its associations with

serious infections, herpes zoster, tuberculosis, gastrointestinal

disorders, and few malignancies.7 8 However, an integrated safety

summary from Phase I-III trials showed stable adverse events, with an

incidence rate of 0.1-3.9 per 100 patient-years, and no new safety signals

in patients who had used tofacitinib for up to 8.5 years.42 Moreover, a recent systematic review with network

meta-analysis concluded that tofacitinib monotherapy had efficacy

comparable to that of currently available biologics, as well as similar

discontinuation rates due to adverse events.43

Current clinical evidence from trials and real-world observations support

the safety of tofacitinib.

We acknowledge that this study had several

limitations. First, we did not consider the costs of monitoring treatments

or treatment of adverse events; this may have led to underestimation of

overall healthcare expenditures for RA treatments. However, given that

monitoring costs and numbers of adverse events from biologics and

tofacitinib may be similar,43 the

absolute changes in healthcare expenditures are not expected to differ

from those we have described. Second, the expected tofacitinib dropout

rate was established on the basis of landmark trials. Patient compliance

and possible treatment switches in real-life clinical treatment settings

were not analysed in this study. Thus, the results of this study should be

interpreted cautiously with respect to the safety, efficacy, and adherence

of tofacitinib and biologics. Third, we assumed constant costs for all

treatments over the study period; in practice, these may be affected by

the dynamic state of the market and a variety of possible interactions

between costs and market share. Finally, structural and parametric

uncertainties from the model were not tested comprehensively. Although we

do not expect deviation from the base-case conclusion, future studies

should assess model uncertainties while considering current clinical

evidence with respect to the effectiveness and safety of novel DMARDs.

Conclusion

The introduction of tofacitinib to the Hospital

Authority Formulary in Hong Kong for the treatment of patients with

uncontrolled RA is expected to lower healthcare expenditures over the

5-year study period. The conclusion is robust in all scenario analyses

with respect to uncertainties in drug costs, as well as in tofacitinib

uptake and compliance.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conception and design: X Li, EWY Chan.

Acquisition of data: X Li, KK Man.

Analysis or interpretation of data: X Li, KK Man, S Pathadka, EWY Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: X Li.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Study supervision: ICK Wong, EWY Chan.

Acquisition of data: X Li, KK Man.

Analysis or interpretation of data: X Li, KK Man, S Pathadka, EWY Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: X Li.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Study supervision: ICK Wong, EWY Chan.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Mr Joseph E Blais and Dr In Hye Suh

from the Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy, The University of Hong

Kong, for their critical review, thoughtful comments, and proofreading of

the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

EWY Chan has received funding from the Early Career

Scheme and the General Research Fund from the Hong Kong Research Grants

Council; the Health and Medical Research Fund, Food and Health Bureau,

Hong Kong SAR Government; the Beat Drugs Fund from the Narcotics Division,

Security Bureau; and the Young Scientist Fund, National Science Foundation

Science Foundation of China, all unrelated to the current work. EWY Chan

has also received research grants from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb,

Janssen Pharmaceutica, Pfizer, and Takeda, and honorarium from the Hong

Kong Hospital Authority, all unrelated to the current work. ICK Wong

received grants from the Hong Kong Research Grants Council, Innovative

Medicines Initiative, Shire, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Eli Lilly, Pfizer,

Bayer, and the European Union FP7 programme, all unrelated to the current

work. ICK Wong was a member of the National Institute for Health and

Clinical Excellence ADHD Guideline Group and the British Association for

Psychopharmacology ADHD guideline group and acted as an advisor to Shire.

X Li received a research grant from the Health and Medical Research Fund,

Food and Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government and consulting fees from

Pfizer, unrelated to this work. KK Man received the CW Maplethorpe

Fellowship and personal fees from IQVIA Holdings, Inc. (previously known

as QuintilesIMS Holdings, Inc.), unrelated to this work. The other

author(s) declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration

Preliminary results from this study were presented

(poster, title: Budget impact analysis of introducing tofacitinib for the

treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Hong Kong) at ISPOR 7th

Asia-Pacific Conference (Tokyo, Japan, 8-11 September 2018). The

conference abstract was published in Value in Health (Volume 21, S80, DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.07.599).

Funding/support

This work was supported by Pfizer Corporation Hong

Kong Limited (grant No. RC170156). The funder had no role in the study

design, data collection and analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or

decision to publish.

References

1. World Health Organization. Chronic

rheumatic conditions. Available from:

http://www.who.int/chp/topics/rheumatic/en/. Accessed 23 Jun 2017.

2. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, et al.

2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of

Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1-26. Crossref

3. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al.

EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with

synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016

update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:960-77. Crossref

4. Curtis JR, Singh JA. Use of biologics in

rheumatoid arthritis: current and emerging paradigms of care. Clin Ther

2011;33:679-707. Crossref

5. Mok CC, Tam LS, Chan TH, Lee GK, Li EK;

Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology. Management of rheumatoid arthritis:

consensus recommendations from the Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology. Clin

Rheumatol 2011;30:303-12. Crossref

6. Ghoreschi K, Jesson MI, Li X, et al.

Modulation of innate and adaptive immune responses by tofacitinib (CP-690,550). J Immunol 2011;186:4234-43. Crossref

7. Lee EB, Fleischmann R, Hall S, et al.

Tofacitinib versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med

2014;370:2377-86. Crossref

8. Fleischmann R, Mysler E, Hall S, et al.

Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib monotherapy, tofacitinib with

methotrexate, and adalimumab with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid

arthritis (ORAL Strategy): a phase 3b/4, double-blind, head-to-head,

randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;390:457-68. Crossref

9. GoodPx. Tofacitinib. Available from:

https://www.goodrx.com/tofacitinib. Accessed 14 Nov 2018.

10. Lee MY, Park SK, Park SY, et al.

Cost-effectiveness of tofacitinib in the treatment of moderate to severe

rheumatoid arthritis in South Korea. Clin Ther 2015;37:1662-76.e2. Crossref

11. Claxton L, Jenks M, Taylor M, et al.

An economic evaluation of tofacitinib treatment in rheumatoid arthritis:

modeling the cost of treatment strategies in the United States. J Manag

Care Spec Pharm 2016;22:1088-102. Crossref

12. Claxton L, Taylor M, Gerber RA, et al.

Modelling the cost-effectiveness of tofacitinib for the treatment of

rheumatoid arthritis in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin

2018;34:1991-2000. Crossref

13. Mehta N, Schneider LK, McCardell E.

Rheumatoid arthritis: selecting monotherapy versus combination therapy. J

Clin Rheumatol 2017 Jan 18. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

14. Drug Office, Department of Health,

Hong Kong SAR Government. Detail Information: XELJANZ TABLETS 5MG.

Available from:

https://www.drugoffice.gov.hk/eps/drug/productDetail/en/consumer/76216.

Accessed 19 Jun 2017.

15. Hong Kong Hospital Authority Drug

Formulary. Available from:

http://www.ha.org.hk/hadf/en-us/Updated-HA-Drug-Formulary/Drug-Formulary.

Accessed 23 Oct 2017.

16. Lai EC, Man KK, Chaiyakunapruk N, et

al. Brief report: databases in the Asia-Pacific region: the potential for

a distributed network approach. Epidemiology 2015;26:815-20. Crossref

17. Raman SR, Man KK, Bahmanyar S, et al.

Trends in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medication use: a

retrospective observational study using population-based databases. Lancet

Psychiatry 2018;5:824-35. Crossref

18. Wong AY, Root A, Douglas IJ, et al.

Cardiovascular outcomes associated with use of clarithromycin: population

based study. BMJ 2016;352:h6926. Crossref

19. Cheung KS, Chan EW, Wong AY, Chen L,

Wong IC, Leung WK. Long-term proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric

cancer development after treatment for Helicobacter pylori: a

population-based study. Gut 2018;67:28-35. Crossref

20. Lau WC, Chan EW, Cheung CL, et al.

Association between dabigatran vs warfarin and risk of osteoporotic

fractures among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. JAMA

2017;317:1151-8. Crossref

21. Law SW, Lau WC, Wong IC, et al.

Sex-based differences in outcomes of oral anticoagulation in patients with

atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:271-82. Crossref

22. Man KK, Chan EW, Ip P, et al. Prenatal

antidepressant use and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in

offspring: population based cohort study. BMJ 2017;357:j2350. Crossref

23. Chan EW, Lau WC, Leung WK, et al.

Prevention of dabigatran-related gastrointestinal bleeding with

gastroprotective agents: a population-based study. Gastroenterology

2015;149:586-95.e3. Crossref

24. Man KK, Coghill D, Chan EW, et al.

Association of risk of suicide attempts with methylphenidate treatment.

JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74:1048-55. Crossref

25. Singh JA, Hossain A, Tanjong Ghogomu

E, et al. Biologics or tofacitinib for rheumatoid arthritis in incomplete

responders to methotrexate or other traditional disease-modifying

anti-rheumatic drugs: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(5):CD012183. Crossref

26. National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013. Apr 2013.

Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg9/chapter/Foreword.

Accessed 7 Jul 2015.

27. Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al.

Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of

cost-effectiveness analyses: Second panel on cost-effectiveness in health

and medicine. JAMA 2016;316:1093-103. Crossref

28. Mai Q, Aboagye-Sarfo P, Sanfilippo FM,

Preen DB, Fatovich DM. Predicting the number of emergency department

presentations in Western Australia: a population-based time series

analysis. Emerg Med Australas 2015;27:16-21. Crossref

29. Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et

al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)

statement. Value Health 2013;16:e1-5. Crossref

30. Fazal SA, Khan M, Nishi SE, et al. A

clinical update and global economic burden of rheumatoid arthritis. Endocr

Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2018;18:98-109. Crossref

31. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Drug review and selection mechanism. Available from:

http://ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_text_index.asp?Content_ID=208041&Lang=ENG&Dimension=100&Parent_ID=206049&Ver=TEXT.

Accessed 29 Mar 2017.

32. National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence. Budget impact test. Available from:

https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-technology-appraisal-guidance/budget-impact-test.

Accessed 19 Jun 2017.

33. Scott AM. Health technology assessment

in Australia: a role for clinical registries? Aust Health Rev

2017;41:19-25. Crossref

34. Canadian Agency for Drugs and

Technologies in Health. About the health technology assessment service.

Available from:

https://www.cadth.ca/about-cadth/what-we-do/products-services/hta.

Accessed 19 Jun 2017.

35. Wong CK, Wu O, Cheung BM. Towards a

transparent, credible, evidence-based decision-making process of new drug

listing on the Hong Kong Hospital Authority Drug Formulary: challenges and

suggestions. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2018;16:5-14. Crossref

36. Goddard M. Competition in healthcare:

good, bad or ugly? Int J Health Policy Manag 2015;4:567-9. Crossref

37. Genovese MC, van Vollenhoven RF,

Wilkinson B, et al. Switching from adalimumab to tofacitinib in the

treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther

2016;18:145. Crossref

38. Vieira MC, Zwillich SH, Jansen JP,

Smiechowski B, Spurden D, Wallenstein GV. Tofacitinib versus biologic

treatments in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis who have had an

inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: results from a

network meta-analysis. Clin Ther 2016;38:2628-41.e5. Crossref

39. Alten R, Krüger K, Rellecke J, et al.

Examining patient preferences in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

using a discrete-choice approach. Patient Prefer Adherence

2016;10:2217-28. Crossref

40. Li Z, An Y, Su H, et al. Tofacitinib

with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in

Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Patient-reported outcomes from

a Phase 3 randomized controlled trial. Int J Rheum Dis 2018;21:402-14. Crossref

41. Augustovski F, Beratarrechea A,

Irazola V, et al. Patient preferences for biologic agents in rheumatoid

arthritis: a discrete-choice experiment. Value Health 2013;16:385-93. Crossref

42. Cohen SB, Tanaka Y, Mariette X, et al.

Long-term safety of tofacitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

up to 8.5 years: integrated analysis of data from the global clinical

trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1253-62. Crossref

43. Bergrath E, Gerber RA, Gruben D, Lukic

T, Makin C, Wallenstein G. Tofacitinib versus biologic treatments in

moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis patients who have had an

inadequate response to nonbiologic DMARDs: systematic literature review

and network meta-analysis. Int J Rheumatol 2017;2017:8417249. Crossref