Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Apr;25(2):127–33 | Epub 28 Mar 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE CME

Non-surgical treatment of knee osteoarthritis

HS Kan1; PK Chan, FHKCOS, FHKAM

(Orthopaedic Surgery)2; KY Chiu, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; CH Yan, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic

Surgery)1; SS Yeung, MScHC(PT), PDPT3; YL Ng, BSc, MHSc4; KW

Shiu, BNurs(Aust)5; Tegan Ho, BMedSc1

1 Department of Orthopaedics and

Traumatology, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Department of Orthopaedics and

Traumatology, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

3 Department of Physiotherapy, MacLehose

Medical Rehabilitation Centre, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

4 Department of Occupational Therapy,

MacLehose Medical Rehabilitation Centre, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

5 Department of Nursing, MacLehose

Medical Rehabilitation Centre, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr PK Chan (lewis@ortho.hku.hk)

Abstract

Knee osteoarthritis is one of the most common

degenerative diseases causing disability in elderly patients.

Osteoarthritis is an increasing problem for ageing populations, such as

that in Hong Kong. It is important for guidelines to be kept up to date

with the best evidence-based osteoarthritis management practices

available. The aim of this study was to review the current

literature and international guidelines on non-surgical treatments for

knee osteoarthritis and compared these with the current guidelines in

Hong Kong, which were proposed in 2005. Internationally, exercise

programmes for non-surgical management of osteoarthritis have been

proven effective, and a pilot programme in Hong Kong for comprehensive

non-surgical knee osteoarthritis management has been successful.

Long-term studies on the effectiveness of such exercise programmes are

required, to inform future changes to guidelines on osteoarthritis

management.

Introduction

Conventionally, osteoarthritis (OA) is considered

as progressive wear and tear of articular cartilage. However, recent

evidence has suggested that it is an inflammatory disease of the entire

synovial joint, comprising not only mechanical degeneration of articular

cartilage but also concomitant structural and functional change of the

entire joint, including the synovium, meniscus (in the knee),

periarticular ligament, and subchondral bone.1

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is one of the most common

degenerative diseases that causes disability in elderly people. An

epidemiological study by Felson et al2

showed that about 30% of all adults have radiological signs of OA; 8.9% of

the adult population has clinically significant OA of the knee or hip, of

which KOA was the most common type. Another study also showed that the

likelihood of OA increases with age.3

The Chinese population has a similar prevalence rate. A nationwide

population-based study in China showed an 8.1% total incidence rate of

symptomatic KOA and increasing prevalence of KOA with age.4 A study in Hong Kong showed that 7% of men and 13% of

women had KOA.5 It is estimated

that the percentage of older adults in the Hong Kong population will

increase from 16.6% in 2016 to 31.1% by 2036.6

Although clinical guidelines for managing lower

limb osteoarthritis (LLOA) in the primary care setting were proposed in

Hong Kong in 2004,7 comparison with

recently updated international guidelines shows some differences from

management in Hong Kong.

In ageing populations, such as that in Hong Kong,

the prevalence of OA is expected to increase. Therefore, it is of

paramount importance to keep updating OA management guidelines so as to

provide the best possible evidence-based management in the primary

setting. This may help to delay progression into end-stage OA and thus

decrease the need for arthroplasty and alleviate long waiting times (the

average waiting time for arthroplasty in public hospitals in Hong Kong is

66 months).5 The aim of the present

study was to compare and contrast the LLOA management guidelines proposed

in Hong Kong7 with international

guidelines, including the Osteoarthritis Research Society International

(OARSI),8 the American Academy of

Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS),9 and

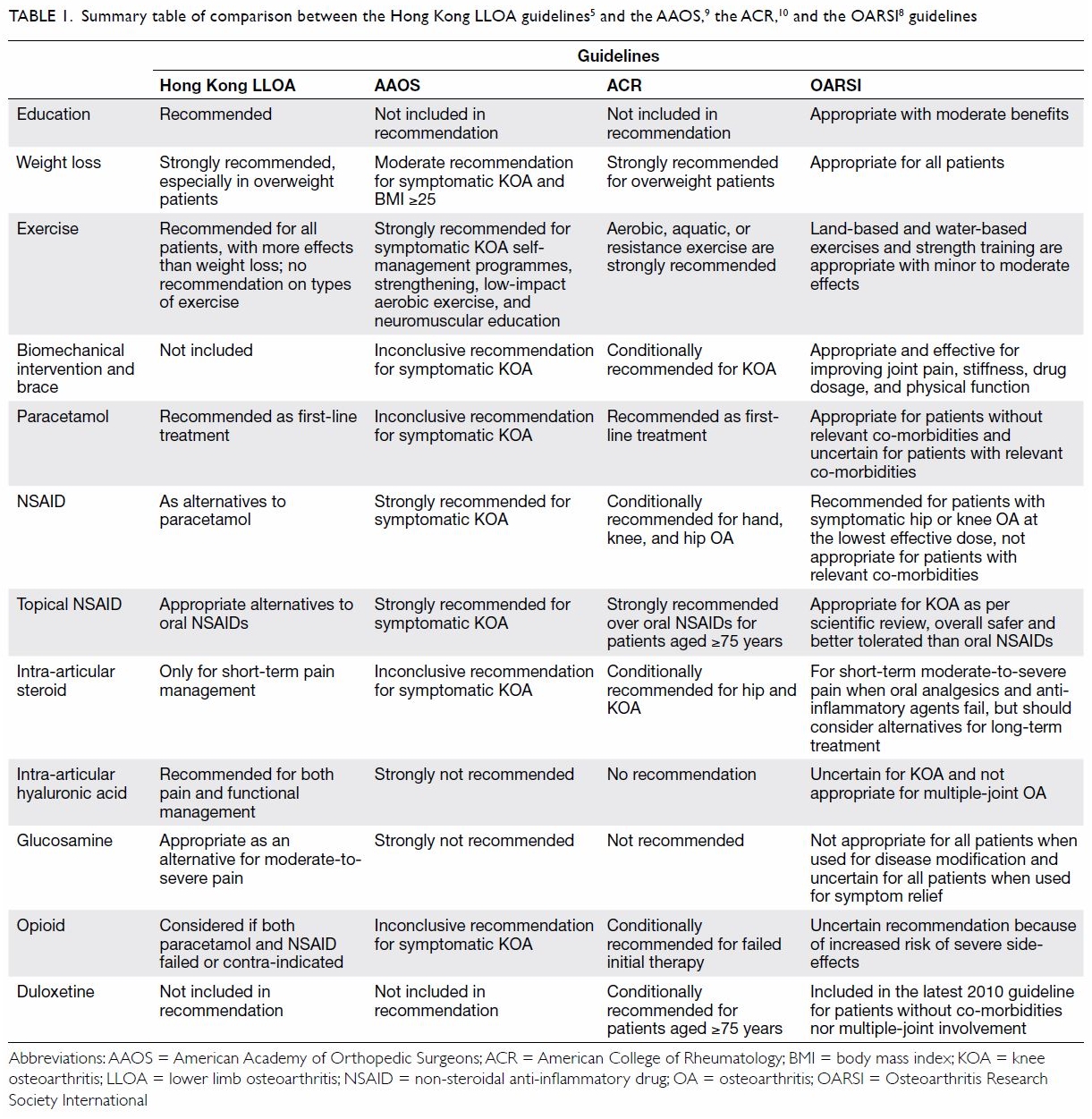

the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) [Table 1].10

Table 1. Summary table of comparison between the Hong Kong LLOA guidelines5 and the AAOS,9 the ACR,10 and the OARSI8 guidelines

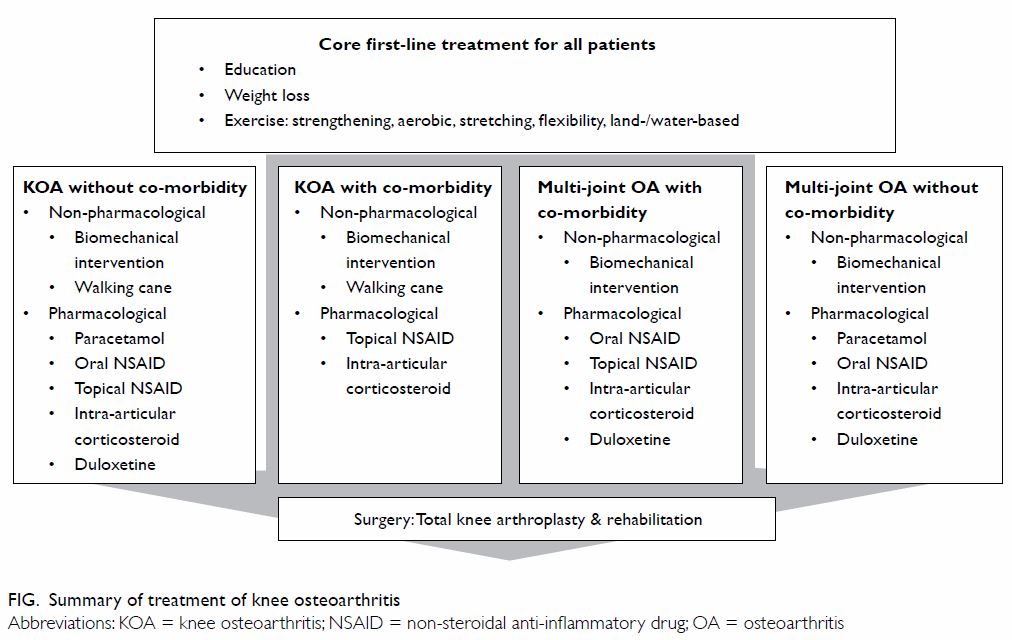

Overview of treatment of knee osteoarthritis

Treatment of KOA can be divided into non-surgical

or surgical treatment. Non-surgical treatment comprises

non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment, and non-pharmacological

treatment comprises core first-line treatment for all patients with OA,

including education, self-management, exercise, and weight reduction.

Other primary non-pharmacological treatments for KOA include walking canes

and biomechanical interventions like braces and orthosis. Pharmacological

therapy may include the use of paracetamol, topical or oral non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or intra-articular corticosteroids.

Surgical procedures are a last resort for end-stage KOA, the most

effective type of which is total knee arthroplasty with rehabilitation

(Fig).

Non-pharmacological treatment of knee osteoarthritis

Education

Both the Hong Kong LLOA and OARSI guidelines aim to

teach patients more about OA; provide them with information about the

disease process, nature, prognosis, investigation, and treatment options

for OA; facilitate changes in health behaviour; and improve compliance

with doctor advice. Counselling can take the form of telephone-based or

group sessions or spouse-assisted training programmes, and this

counselling works in combination with other treatment approaches.

Weight management

The Hong Kong LLOA and other international

guidelines agree that weight reduction plays a key role in treating all OA

patients. Obesity is strongly associated with an increased risk of

developing OA, the requirement of arthroplasty, and physical disability.11 A meta-analysis reported that

obesity increases the risk of developing KOA five-fold, and overweight

increases the risk two-fold.12 The

main form of weight management is lifestyle modification, which may

include a low-calorie diet, increased physical activity, or anti-obesity

drugs; in severe cases, surgery like gastric bypass, adjustable gastric

banding, or sleeve gastrectomy should be recommended. Recent studies have

proven the significance of weight modification: evidence has shown that

knee pain is reduced by over 50% after body weight reduction by around

10%,13 and weight reduction may

drop the risk of developing symptomatic KOA by 50%.2 It is expected that weight management would also be

effective in Hong Kong. A local study investigating the risk factors of

KOA showed that overweight was the greatest risk factor for KOA in Hong

Kong and that 64% of the investigated Hong Kong patients with KOA were

overweight.5

Exercise

Exercise aims to reduce pain and improve general

mobility and joint function; more intensive exercise can strengthen the

muscle around the knee joint. Exercise is one form of first-line treatment

advocated by the Hong Kong LLOA guidelines. There is no recommendation

regarding the type of exercise to do, suggesting that it has lower

efficacy in reduction of pain and disability compared with weight loss.

Exercise is now universally recommended by the other international

guidelines. Recent studies suggest the important role of exercise in OA

management, and different types of exercise have different benefits in KOA

treatment. Targeted strengthening exercises, aerobic exercise, stretching,

and flexibility exercises are recommended by AAOS, ACR, and OARSI.

A meta-analysis found that land-based exercise

(especially exercise like Tai Chi) has the strongly favourable benefits of

improving pain and physical function in patients with KOA; the duration

and type of exercise programme in the meta-analyses varied widely, but the

general components of the programmes are strength training, active range

of motion exercise, and aerobic activity. Although positive results were

obtained for land-based exercise, they did not favour any specific

exercise regimen or duration.14

A study in 2016 found that water-based exercise has

short-term benefits for function but minor benefits for pain.15 It is suggested for patients with functional or

mobility limitations.

Strength training exercises include primarily

resistance-based lower limb and quadriceps strengthening exercises. A

meta-analysis in 2011 showed moderate benefits of reducing pain and

improving physical function. However, the duration of exercise varied

among these programmes.16

Biomechanical intervention and walking canes

Biomechanical intervention and walking canes are

not included in the Hong Kong LLOA guidelines but are regarded as

appropriate and effective by the OARSI guidelines. A literature review

suggests that knee braces and foot orthoses could have a positive impact

on decreasing pain and stiffness and improving physical function. However,

conclusions about their effectiveness have yet to be made because of the

lack of clinical trials and the heterogeneity of interventions among the

studies reviewed.17 Both the OARSI

and ACR guidelines suggest that walking canes are appropriate for KOA but

not appropriate for multi-joint OA because they may increase weight

loading on other affected joints.18

In contrast, the AAOS guidelines are inconclusive about this topic.

Pharmacological treatment of knee osteoarthritis

Paracetamol

The Hong Kong LLOA guidelines stipulate that

paracetamol is a key medication for knee OA. It is regarded as the

first-line treatment for mild to moderate OA pain because of its efficacy,

safety, and cost, and it is also the preferred essential component of

long-term pain control. However, it is no longer the first-line treatment

suggested by OARSI, as a meta-analysis showed that paracetamol has low

efficacy for pain management.19

The OARSI guidelines recommend that paracetamol be given in conservative

doses and durations, as there is concern regarding an increasing risk of

gastrointestinal disturbance and multi-organ failure.20

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

The Hong Kong LLOA and ACR guidelines suggest

NSAIDs as an alternative to paracetamol, whereas the OARSI guidelines

suggest NSAIDs as the preferred first-line pharmacological treatment,

because systematic reviews have found that NSAIDs are superior to

paracetamol for resting and overall pain.21

Although NSAIDs are recommended in patients without risk, OARSI is

reserved in its recommendation for NSAID use in patients with a high risk

of co-morbidities. Non-selective NSAIDs have greater associated upper

gastrointestinal risks, whereas selective NSAIDs have more cardiovascular

side-effects like myocardial infarction; in addition, both selective and

non-selective NSAIDs cause side-effects like hypertension, congestive

heart failure, and renal toxicity. The AAOS recommendations about NSAIDs

are inconclusive for symptomatic KOA. The Hong Kong LLOA guidelines and

all international guidelines strongly suggest that topical NSAIDs (eg,

topical diclofenac) be considered as an option for knee-only OA, but their

applicability for multiple joint OA is still uncertain. Both topical and

oral NSAIDs have similar efficacy and significant benefits over placebo.

Topical ones have less gastrointestinal risk but a higher risk of

dermatological side-effects.22

Intra-articular steroids

The Hong Kong LLOA, ACR, and OARSI guidelines

recommend that steroids only be used in acute exacerbations of joint

inflammation, as frequent use can result in cartilage or joint damage and

increase infection risk. The AAOS recommendation on this topic is

inconclusive.

Intra-articular hyaluronic acid

The Hong Kong LLOA guidelines recommend hyaluronic

acid for management of KOA for both pain reduction and functional

improvement, as it is considered to have effects comparable to those of

oral NSAIDs or steroid injections. However, the AAOS and ACR guidelines do

not recommend the use of hyaluronic acid because of the lack of data from

randomised controlled trials on either its benefits or safety. The OARSI

recommendation is also uncertain because of the inconclusive results of

recent meta-analyses. A meta-analysis with blinded trials found only small

benefits for pain.23

Glucosamine

The Hong Kong LLOA guidelines consider glucosamine

to have moderate to large effects on pain and disability in LLOA compared

with placebo, and it is associated with few side-effects. It is used

commonly as an alternative treatment, especially for mild to moderate KOA.

However, all the international guidelines strongly recommend against the

use of glucosamine because recent randomised controlled trials showed

similar effects to placebo, with independent trials showing smaller

effects than commercially funded ones.24

Opioids

In Hong Kong, opioid analgesics are considered if

paracetamol is inadequate and NSAIDs are contraindicated, ineffective, or

poorly tolerated. The ACR also suggested that opioids may be an

alternative in failed initial therapy. However, with reference to

international guidelines for OA management, we should consider the

long-term overall usefulness of opioids. Although they have benefits for

pain and physical function, compared with those who are not, patients

taking opioids have a chance of adverse withdrawal effects that is 4 times

higher, and a risk of developing serious side events, including fractures

and cardiovascular events, that is 3 times higher.25 International guidelines provide a similar

recommendation, AAOS makes an inconclusive recommendation, and OARSI is

uncertain about opioid use because of the increased risk of side-effects.

Duloxetine

The use of duloxetine is not suggested by the Hong

Kong LLOA guidelines or AAOS. However, OARSI and AAOS suggest that

co-existing depression and neuropathic pain contribute to the overall pain

syndrome, as the pain experienced in OA is multifactorial. A study showed

that duloxetine has pain reduction benefits over placebo.26 Therefore, it is recommended as a potential adjunct

to conventional OA treatment for pain reduction.27

Models of knee osteoarthritis management and comparison

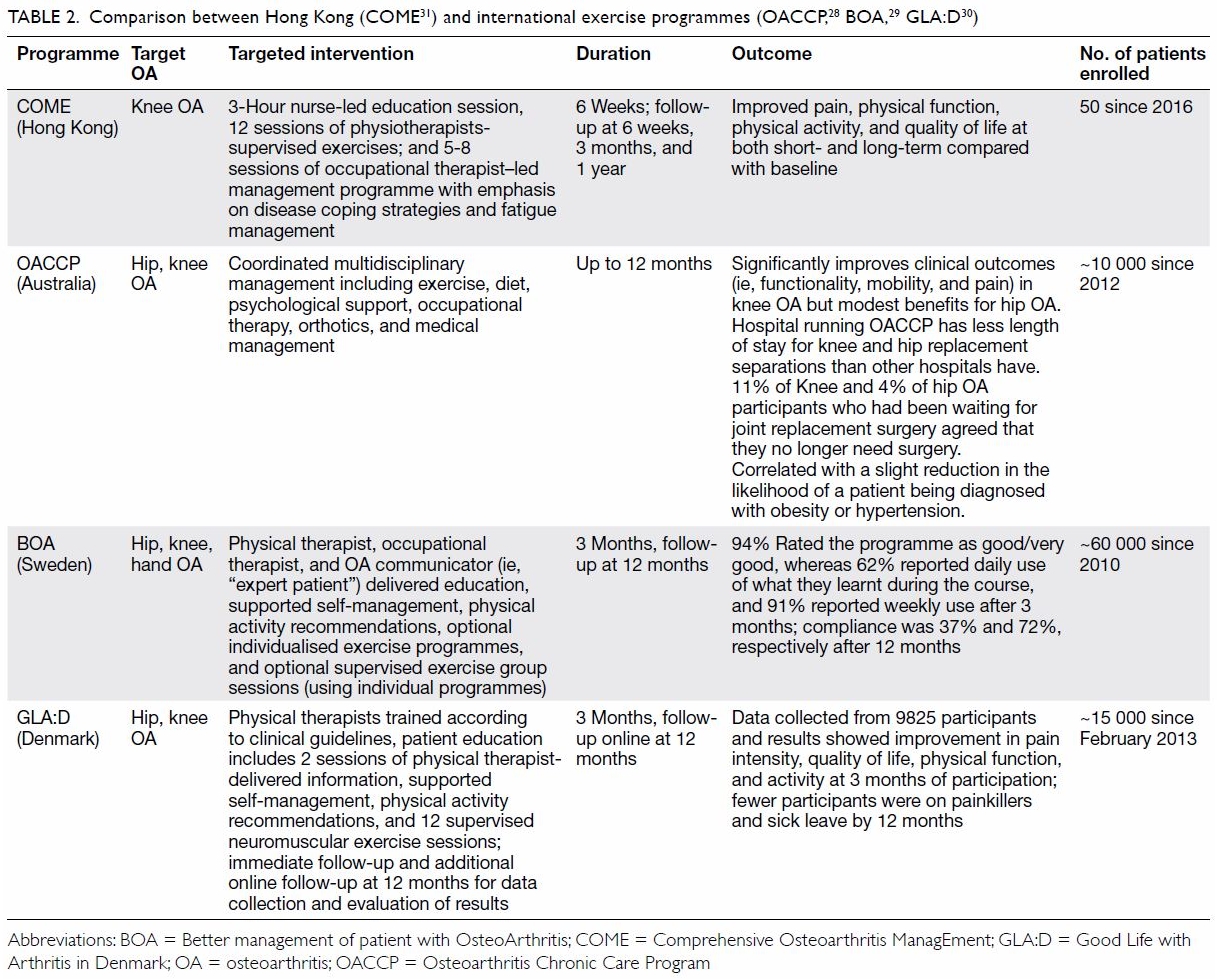

As mentioned above, an increasing number of studies

has proven the effectiveness of exercise and physiotherapy on OA

management; with the increasing ageing of the population, it would be

ideal for Hong Kong to develop a well-established exercise programme for

patients with OA as both a non-surgical treatment and follow-up. There

have already been different well-established exercise programmes for

non-surgical OA management throughout the world, and they have achieved

great outcomes. Successful examples include the Osteoarthritis Chronic

Care Program in Australia (OACCP),28

Better management of patients with OsteoArthritis in Sweden,29 and Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (Table

2).30 All of these

programmes have been proven to improve patients’ pain, mobility, physical

function, and quality of life. The OACCP has also proven that an exercise

programme helps to decrease the demand for arthroplasty; 11% of knee and

4% of hip OA participants who had been waiting for arthroplasty agreed

they no longer needed surgery. Different programmes may have minor

arrangements targeting their patients, but their content and training

duration are generally similar; these programmes consist of education

delivered by physiotherapists and sharing from “expert” patients,

supported self-management, and supervised neuromuscular exercise sessions

of progressive intensity. These programmes usually last at least 3 months

with follow-up for 12 months.

Table 2. Comparison between Hong Kong (COME31) and international exercise programmes (OACCP,28 BOA,29 GLA:D30)

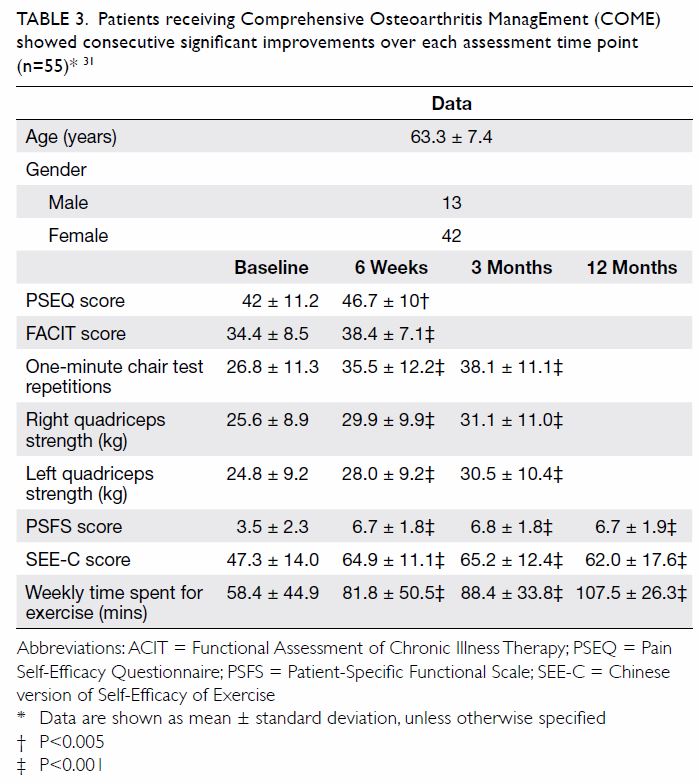

Comprehensive Osteoarthritis ManagEment (COME)

initiated in 2016 is a pioneering programme for Hong Kong.31 The COME programme is a multidisciplinary exercise

programme for non-surgical KOA that consists of a 6-week intensive

training programme: the components include a 3-hour nurse-led education

session, 12 sessions of physiotherapist-supervised exercises; and five to

eight sessions of an occupational therapist–led management programme with

emphasis on disease coping strategies and fatigue management. After 1

year, patients enrolled in the COME programme reported short-term

improvement in Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire, Functional Assessment of

Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue Scale, physical capacity assessed by

quadriceps strength, and physical function assessed by one-minute chair

test. One-year improvement showed in Patient-Specific Functional Scale,

Chinese version of Self-Efficacy of Exercise, and weekly time spent for

exercise (Table 3).

Table 3. Patients receiving Comprehensive Osteoarthritis ManagEment (COME) showed consecutive significant improvements over each assessment time point (n=55)31

Conclusion

In ageing populations, the prevalence of KOA is

expected to increase; thus, there is a need for consensus on non-surgical

OA management, so as to improve outcomes for patients with OA and to

decrease the burden of arthroplasty. Various exercise programmes for

non-surgical OA management have been shown to be effective for improvement

of pain, physical function, mobility, and quality of life, and these

programmes have even decreased the need and waiting times for

arthroplasty. Long-term follow-up of such exercise programmes should be

considered to further assess their outcomes.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design: RHS Kan, PK Chan, KY Chiu, CH

Yan.

Acquisition of data: T Ho.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SS Yeung, YL Ng, KW Shiu.

Drafting of the manuscript: RHS Kan.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: RHS Kan, PK Chan, KY Chiu, CH Yan, T Ho.

Acquisition of data: T Ho.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SS Yeung, YL Ng, KW Shiu.

Drafting of the manuscript: RHS Kan.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: RHS Kan, PK Chan, KY Chiu, CH Yan, T Ho.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest are declared by the

authors.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Mobasheri A, Batt M. An update on the

pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2016;59:333-9. Crossref

2. Felson DT, Zhang Y, Anthony JM, Naimark

A, Anderson JJ. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee

osteoarthritis in women. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med

1992;116:535-9. Crossref

3. Michael JW, Schlüter-Brust KU, Eysel P.

The epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoarthritis of

the knee. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010;107:152-62. Crossref

4. Tang X, Wang S, Zhang Y, Niu J, Tao K,

Lin J. The prevalence of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in China: results

from China health and retirement longitudinal study. Osteoarthritis

Cartilage 2015;23(Suppl 2):A176-7. Crossref

5. The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Osteoarthritis in Hong Kong Chinese—prevalence, aetiology and prevention.

2001. Available from: http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/ipro/010306e.htm. Accessed 14

Dec 2018.

6. Census and Statistics Department, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Hong Kong population projections for 2017-2066.

Available from:

https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/media_workers_corner/pc_rm/hkpp2017_2066/index.jsp.

Accessed 14 Dec 2018.

7. Department of Community and Family

Medicine, Chinese University of Hong Kong; Centre for Health Education and

Health Promotion. Clinical guidelines for managing lower-limb

osteoarthritis in Hong Kong primary care setting. Department of Community

and Family Medicine, Chinese University of Hong Kong; 2004.

8. McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC,

et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee

osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:363-88. Crossref

9. Jevsevar DS. Treatment of osteoarthritis

of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg

2013;21:571-6. Crossref

10. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et

al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of

nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the

hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care and Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:465-74. Crossref

11. Wluka AE, Lombard CB, Cicuttini FM.

Tackling obesity in knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013;9:225-35.

Crossref

12. Zheng H, Chen C. Body mass index and

risk of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of

prospective studies. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007568. Crossref

13. Vincent HK, Heywood K, Connelly J,

Hurley RW. Obesity and weight loss in the treatment and prevention of

osteoarthritis. PM R 2012;4(5 Suppl):S59-67. Crossref

14. Kang JW, Lee MS, Posadzki P, Ernst E.

T’ai chi for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000035. Crossref

15. Bartels EM, Juhl CB, Christensen R, et

al. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(3):CD005523. Crossref

16. Jansen MJ, Viechtbauer W, Lenssen AF,

Hendriks EJ, de Bie RA. Strength training alone, exercise therapy alone,

and exercise therapy with passive manual mobilisation each reduce pain and

disability in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J

Physiother 2011;57:11-20. Crossref

17. Raja K, Dewan N. Efficacy of knee

braces and foot orthoses in conservative management of knee

osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2011;90:247-62.

Crossref

18. Jones A, Silva PG, Silva AC, et al.

Impact of cane use on pain, function, general health and energy

expenditure during gait in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomised

controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:172-9. Crossref

19. Bannuru RR, Dasi UR, McAlindon TE.

Reassessing the role of acetaminophen in osteoarthritis: systematic review

and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18(Suppl 2):S250. Crossref

20. Craig DG, Bates CM, Davidson JS,

Martin KG, Hayes PC, Simpson KJ. Staggered overdose pattern and delay to

hospital presentation are associated with adverse outcomes following

paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;73:285-94. Crossref

21. Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Judd MG, Catton

M, Hochberg MC, Wells G. Acetaminophen for osteoarthritis. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2006;(1):CD004257. Crossref

22. Chou R, Helfand M, Peterson K, Dana T,

Roberts C. Comparative effectiveness and safety of analgesics for

osteoarthritis. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

(US); 2006.

23. Rutjes AW, Jüni P, da Costa BR, Trelle

S, Nüesch E, Reichenbach S. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the

knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med

2012;157:180-91. Crossref

24. Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al.

OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis:

part III: changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of

research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage

2010;18:476-99. Crossref

25. da Costa BR, Nüesch E, Kasteler R, et

al. Oral or transdermal opioids for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(9):CD003115. Crossref

26. Chappell AS, Desaiah D, Liu-Seifert H,

et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the

efficacy and safety of duloxetine for the treatment of chronic pain due to

osteoarthritis of the knee. Pain Pract 2011;11:33-41. Crossref

27. Yu SP, Hunter DJ. Managing

osteoarthritis. Aust Prescr 2015;38:115-9. Crossref

28. Deloitte Access Economics.

Osteoarthritis Chronic Care Program evaluation. Agency for Clinical

Innovation. 2014. Available from:

https://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/259794/oaccp-evaluation-feb-2015.pdf.

Accessed 15 Dec 2018.

29. Thorstensson CA, Garellick G, Rystedt

H, Dahlberg LE. Better management of patients with OsteoArthritis:

development and nationwide implementation of an evidence-based supported

osteoarthritis self-management programme. Musculoskeletal Care

2015;13:67-75. Crossref

30. Skou ST, Roos EM. Good Life with

osteoarthritis in Denmark (GLA:DTM): a nationwide implementation of

clinical recommendations of education and supervised exercise in knee and

hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017;25(Suppl 1):S389-90. Crossref

31. Chan PK, Yeung SS, Siu SW, et al.

Comprehensive Osteoarthritis Management (COME) Programme—Multidisciplinary

exercise training programme for patients with age-related osteoarthritis

of knee. Hong Kong. Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on

Healthy Aging “Aging, Health, Happiness”; 2018 Mar 10-11; Hong Kong. Hong

Kong: LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong; 2018: 70.