Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Apr;25(2):159.e1–2

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Catheterised hutch diverticulum masquerading as

intraperitoneal bladder perforation

Victor SH Chan, MB, BS, FRCR (UK)1; WM

Kwok, MB, BS2; Stephen CW Cheung, MRCP, FHKAM (Radiology)1

1 Department of Radiology, Queen Mary

Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Department of Accident and Emergency,

Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Victor SH Chan (victorchansh@gmail.com)

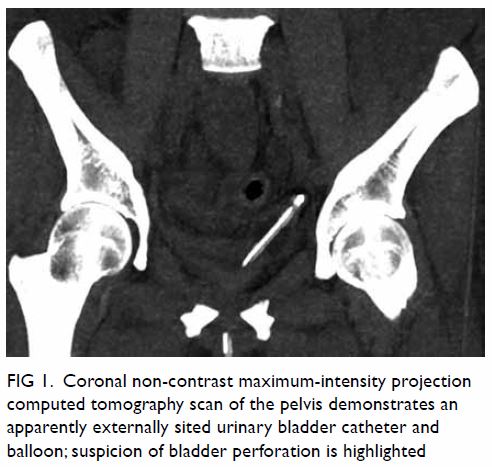

A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed in a

64-year-old man with a history of end-stage renal failure to evaluate

recent acute-on-chronic graft failure. To conserve remnant renal function,

no intravenous contrast was administered. There was no hydronephrosis but

the balloon of the indwelling Foley catheter was seen adjacent to but

exterior to the bladder (Fig 1). No evidence of pneumoperitoneum was seen.

Free fluid was noted in the pelvis, compatible with the history of

peritoneal dialysis. The suspicion of perforated urinary bladder was

conveyed to the referring physicians, and the patient was admitted for

further evaluation. No abdominal distension, tenderness or guarding was

elicited on physical examination. Urine output via the indwelling catheter

was within normal limits. The patient was haemodynamically stable with no

leukocytosis.

Figure 1. Coronal non-contrast maximum-intensity projection computed tomography scan of the pelvis demonstrates an apparently externally sited urinary bladder catheter and balloon; suspicion of bladder perforation is highlighted

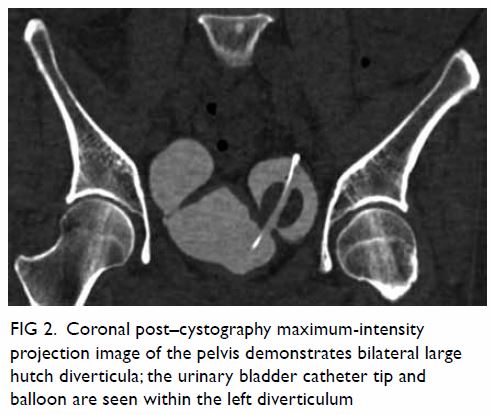

Computed tomography cystography was performed: 20

mL of water-soluble contrast medium (Omnipaque 300) was diluted in 500 mL

of normal saline. Transurethral perfusion of 250 mL of the prepared

contrast medium was performed by free gravitational flow. Pre-instillation

and post-instillation CT cystography (5 minutes and delayed 10 minutes)

was performed. No intravenous contrast was administered.

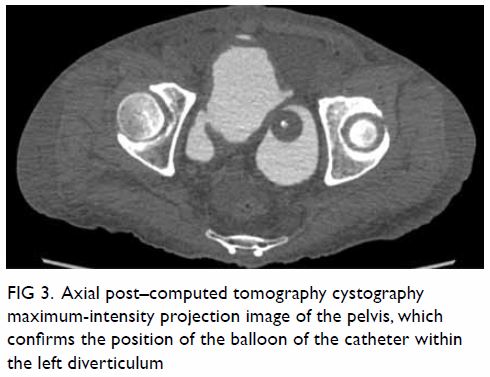

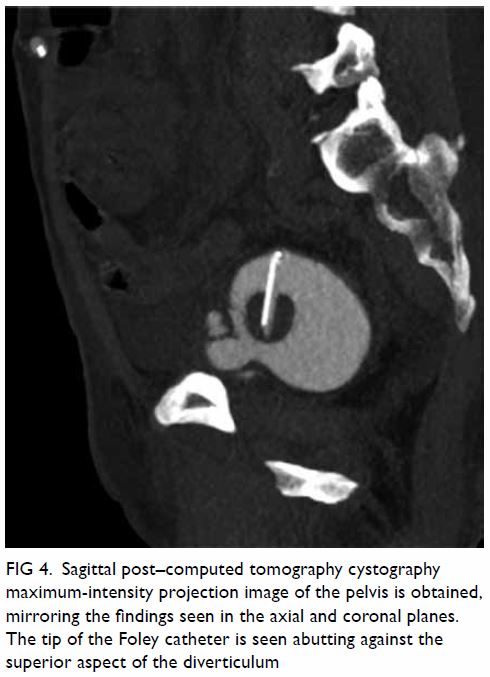

Cross-sectional imaging revealed two large urinary

bladder diverticula sited posteriorly, close to the native vesicoureteric

junctions. The right diverticulum measured 3.8 × 4.6 cm with a 0.9-cm

neck; the left diverticulum measured 4.5 × 5.8 cm with a 1.1-cm neck. On

coronal images, a “Mickey-Mouse” appearance was noted, compatible with

bilateral hutch diverticula. The inflated balloon of the urinary catheter

was sited within the left diverticulum (Figs 2 3 4). The bladder contour was smooth. No evidence of

intraperitoneal rupture was demonstrated. On pre-cystography images, the

appearance had mimicked an externally sited catheter balloon due to the

collapsed state of the bladder.

Figure 2. Coronal post–cystography maximum-intensity projection image of the pelvis demonstrates bilateral large hutch diverticula; the urinary bladder catheter tip and balloon are seen within the left diverticulum

Figure 3. Axial post–computed tomography cystography maximum-intensity projection image of the pelvis, which confirms the position of the balloon of the catheter within the left diverticulum

Figure 4. Sagittal post–computed tomography cystography maximum-intensity projection image of the pelvis is obtained, mirroring the findings seen in the axial and coronal planes. The tip of the Foley catheter is seen abutting against the superior aspect of the diverticulum

Spontaneous bladder perforation is rare but

potentially fatal. Most such cases present with features of peritonitis.

Some possible aetiologies include gonorrhoeal infection, radiation

therapy, diabetes mellitus, neurogenic bladder, bladder diverticula, and

indwelling urinary catheter.1 2 As our patient was largely pain-free with minimal

abdominal symptoms, the overall clinical evidence did not favour bladder

rupture even though the CT images were alarming.

Saline instillation and bedside ultrasound for

rapid disposition of polytrauma patients and early diagnosis of bladder

rupture has been described in the literature, with sensitivity reaching

90%.3 In cases with low clinical

risk for perforation and when the patient is unfit for immediate CT,

instillation of sterile saline to distend the bladder followed by

ultrasound assessment provides a possible alternative to exclude bladder

perforation. However, ultrasound results are highly operator-dependent and

this procedure should be performed only in carefully selected patients. In

experienced hands, following retrograde instillation of approximately 300

mL of sterile saline via the catheter, this imaging modality can be used

to determine presence of ascites, evaluate the distension and

configuration of the urinary bladder, look for bladder diverticula, and

determine the position of the catheter balloon. This can be performed at

the bedside for critically ill patients, involves no radiation and removes

the risk of intravenous contrast-related anaphylaxis.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept, image

acquisition, image and data interpretation, manuscript drafting and

critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors had full

access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Relevant patient consent was obtained for the

purpose of this case study.

References

1. Sawalmeh H, Al-Ozaibi L, Hussein A,

Al-Badri F. Spontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder (SRUB); A case

report and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2015;16:116-8. Crossref

2. Ogawa S, Date T, Muraki O.

Intraperitoneal urinary bladder perforation observed in a patient with an

indwelling urethral catheter. Case Rep Urol 2013;2013:765704. Crossref

3. Karim T, Topno M. Bedside sonography to

diagnose bladder trauma in the emergency department. J Emerg Trauma Shock

2010;3;305. Crossref