Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Feb;25(1):13–20 | Epub 18 Jan 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Survey on prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in

an Asian population

CH Yee, MB, BS, FRCSEd; CK Chan, MB, ChB, FRCSEd;

Jeremy YC Teoh, MB, BS, FRCSEd; Peter KF Chiu, MB, ChB, FRCSEd; Joseph HM

Wong, MB, BS, FRCSEd; Eddie SY Chan, MB, ChB, FRCSEd; Simon SM Hou, MB,

BS, FRCSEd; CF Ng, MB, BS, FRCSEd

SH Ho Urology Centre, The Chinese University of

Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CH Yee (yeechihang@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Lower urinary

tract symptoms (LUTS) have a strong effect on socio-economic and

individual quality of life. The aim of the present study was to

investigate the prevalence of LUTS in an Asian population.

Methods: A telephone survey of

individuals aged ≥40 years and of Chinese ethnicity was conducted. The

survey included basic demographics, medical and health history, drinking

habits, International Prostate Symptom Score, overactive bladder symptom

score, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) score, and Short Form

(SF)–12v2 score.

Results: From March to May 2017,

18 881 calls were made, of which 1543 fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

In the end, 1000 successful respondents were recruited (302 men and 698

women). Age-adjusted prevalence of overactive bladder syndrome was

15.1%. The older the respondent, the more prevalent the storage symptoms

and voiding symptoms (storage symptoms: r=0.434, P<0.001;

voiding symptom: r=0.190, P<0.001). Presence of hypertension

and diabetes were found to be significantly and positively correlated

with storage and voiding symptoms. Storage and voiding symptoms were

found to affect PHQ-9 scores (storage symptoms: r=0.257,

P<0.001; voiding symptoms: r=0.275, P<0.001) and SF-12v2

scores (storage symptoms: r=0.467, P<0.001; voiding symptoms:

r=0.335; P<0.001). Nocturia was the most prominent symptom

among patients who sought medical help for their LUTS.

Conclusions: Lower urinary tract

symptoms are common in Asian populations. Both storage and voiding

symptoms have a negative impact on mental health and general well-being

of individuals.

New knowledge added by this study

- Past studies on lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) prevalence have mainly involved men. The present study provides data on the prevalence of LUTS in both sexes.

- The present study is among the few studies which have correlated LUTS with general well-being and mental health.

- There is a discrepancy between LUTS and medical help seeking behaviour. The present study provides insight into symptoms that drive patients to seek medical help.

- Understanding the prevalence of LUTS will help estimate the associated workload and expense needed to take care of this group of patients.

- The discrepancy between LUTS prevalence and the medical help seeking behaviour of patients with LUTS suggests a need for public health education.

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) can affect

patients of both sexes and of all ages.1

Although LUTS are regarded by the most cultures as an inevitable

consequence of ageing, bother from LUTS varies among populations.2 Assessment of bother from symptoms is important,

because the degree of bother affects quality of life (QoL) and medical

help seeking behaviour.3 4

There are few studies investigating the correlation

between LUTS and drinking habits, especially among Asian populations.

Daily routines and dietary habits are largely dependent on cultural

background; therefore, LUTS might vary in this perspective. In addition,

up-to-date evidence on the impact of LUTS on mental health, as well as on

the general well-being of an individual, is scarce. Most studies have

investigated LUTS as a collective symptom entity.5

Few studies have investigated the relationship between individual symptoms

and psychological stress.

The purpose of the present study is to provide an

updated perspective on LUTS in an Asian population including both men and

women. The present study aimed to clarify the prevalence of the

subcategories of LUTS—voiding symptoms, storage symptoms, and

nocturia—through a telephone survey. Furthermore, we investigated medical

background and lifestyle factors that might have precipitated LUTS. Last,

we assessed the effect of LUTS on the mental health and general well-being

of individual patients. We also evaluated the level of bother caused by

individual symptoms in relation to medical help seeking behaviour.

Methods

This was a random telephone survey of the general

population in Hong Kong. Inclusion criteria were men or women aged ≥40

years of Chinese ethnicity. Subjects who were not able to comprehend the

telephone survey were excluded from the study. Local census data report a

≥40-year-old population of 3 875 800 in 2013.6

Anticipating a confidence level of 95% and margin of error of 3%, 1000

respondents were targeted to complete the survey.

The survey consisted of seven parts. Basic

demographics were collected, including age, sex, marital status, education

level, occupation, and individual monthly income. Medical background and

drinking habits were explored by questions on smoking history, beverage

consumption habits, general medical and mental health history, urological

history, and medical help seeking behaviour. Any LUTS were assessed with

the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) or the overactive bladder

symptom score.7 The Patient Health

Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used to assess depressive symptoms among the

respondents. The PHQ-9 scores ≥10 have a sensitivity of 88% and a

specificity of 88% for major depression. The PHQ-9 scores of 5, 10, 15,

and 20 represent mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression,

respectively.8 The Short Form

(SF)–12v2 Health Survey was used to assess health-related QoL. The

International Index of Erectile Function was used to assess sexual

function in male respondents who were sexually active in the preceding 4

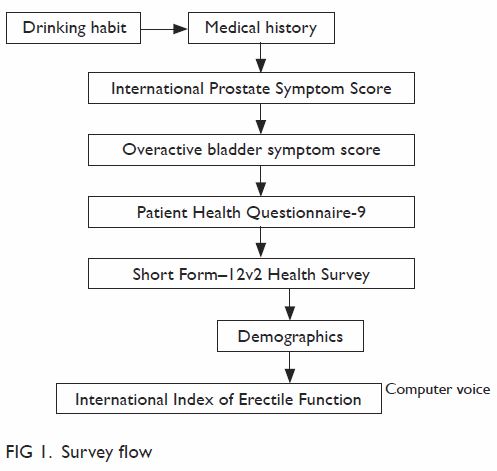

weeks.9 Figure 1 shows the survey question flow. To avoid

unnecessary embarrassment and to improve compliance, questions on sexual

health were asked by a pre-recorded computer-generated voice programme.

Subjects answered the questions by pressing the appropriate number key on

the phone keypad.

The interviews were carried out from March to May

2017. To minimise the sampling error, telephone numbers were first

selected randomly from an updated telephone directory as seed numbers.

Another three sets of numbers were then generated using randomisation of

the last two digitals to recruit unlisted numbers. Duplicate numbers were

screened out, and the remaining numbers were mixed in a random order to

become the final sample. Interviews were carried out by experienced

interviewers, between 18:00 and 22:00 on weekdays or at other convenient

times, including weekends and public holidays, arranged with suitable

subjects. Upon successful contact with a target household, one qualified

member of the household was selected among those family members using the

last-birthday random selection method (ie, the respondent aged ≥40 years

in a household who had most recently had a birthday would be selected to

participate in the telephone interview). Principles of the Declaration of

Helsinki were followed. The study was performed in compliance with Good

Clinical Practice. All participants provided informed consent before

participating in the study.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise

the clinical characteristics of the survey cohort. Spearman correlation

was used to investigate the relationships between different age-groups and

severity of LUTS. Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test was applied for

categorical data. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression

analyses were performed to identify clinical covariates that were

significantly associated with LUTS. The P value of <0.05 were

considered statistically significant. The SPSS (Windows version 24.0; IBM

Corp, Armonk [NY], US) was used for all calculations.

Results

A total of 18 881 calls were made, among which 17

338 were invalid cases, including non-residential lines, invalid lines,

non-eligible respondents, or having the line cut immediately before the

survey could start. Another 543 eligible respondents were excluded because

they refused to participate in the survey after being informed of the

nature of the study. In the end we received 1000 valid responses,

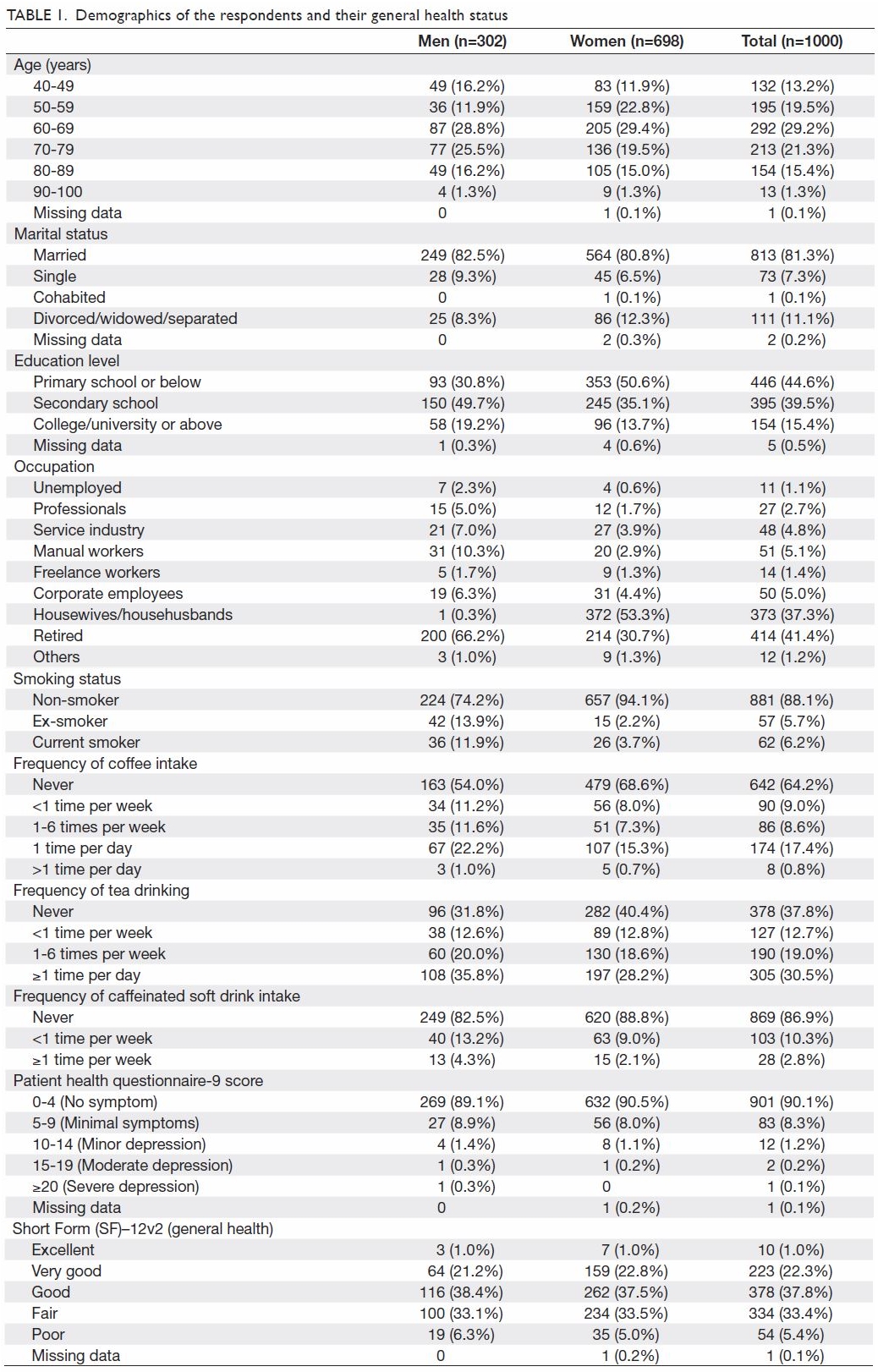

achieving a response rate of 64.8% after excluding the invalid numbers. Table 1 includes the demographics of the respondents

and their drinking habits. Most respondents did not regularly drink

coffee, but 30.5% of respondents reported drinking tea more than once per

day.

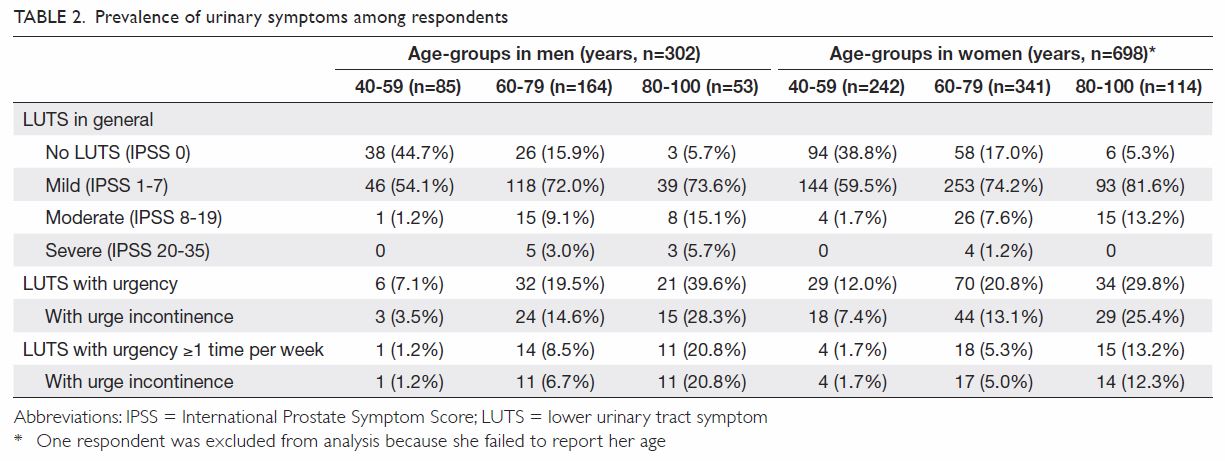

In total, 774 respondents (77.4%) reported a

certain degree of LUTS (Table 2). Among respondents with LUTS, 89.5% had

mild symptoms, 8.9% had moderate symptoms, and 1.6% experience severe

symptoms. Men had more LUTS than did women (mean ± standard deviation

[SD]: men, 3.62 ± 4.86; women, 2.56 ± 3.34; P=0.002). The older the

subject, the poorer the LUTS and QoL scores (mean IPSS: 40-59 years, 1.37

± 2.05; 60-79 years, 3.32 ± 4.28; ≥80 years, 4.48 ± 4.45; P<0.001; mean

QoL score: 40-59 years, 1.15 ± 0.91; 60-79 years, 1.85 ± 1.13; ≥80 years,

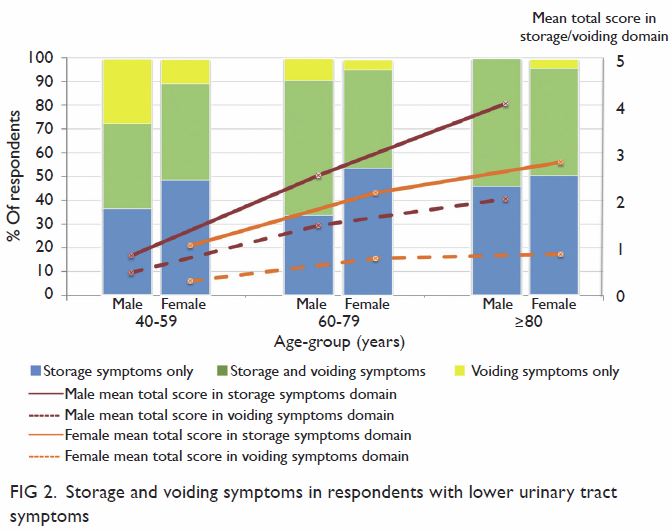

2.25 ± 1.13; P<0.001). In the storage symptom domain of IPSS, sex did

not show any significant difference in mean total storage symptom score

(men, 2.32 ± 2.48; women, 1.91 ± 1.97; P=0.052). The older the age, the

more prevalent the storage and voiding symptoms (storage symptom score: r=0.434,

P<0.001; voiding symptom score: r=0.190, P<0.001). Mean

total storage symptom score across different age-groups were: 40-59 years,

1.01 ± 1.29; 60-79 years, 2.30 ± 2.27; ≥80 years, 3.23 ± 2.25; P<0.001.

The age-adjusted prevalence of any urgency symptom in our survey was 15

096 per 100 000 population. If we only include symptoms of urgency more

than once per week, the age-adjusted prevalence was 4070 per 100 000

population. Furthermore, more storage symptoms than voiding symptoms were

experienced by respondents at any age-group (Fig 2).

If we exclude nocturia 1 time per night only as

part of LUTS or part of storage symptoms, a total of 191 (63.2%) men were

found to have LUTS in this survey. In this group of respondents, 71

(37.2%) reported only having storage symptoms, 19 (9.9%) reported only

having voiding symptoms, and 101 (52.9%) reported having both storage and

voiding symptoms. Similarly, 348 (49.9%) women were found to have LUTS:

181 (52.0%) reported only having storage symptoms, 19 (5.5%) reported only

having voiding symptoms, and 148 (42.5%) reported having both storage and

voiding symptoms.

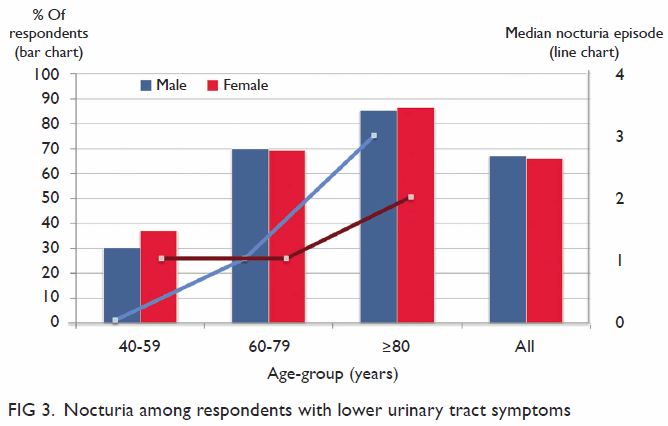

Figure 3 shows the prevalence of nocturia among the

respondents with LUTS. Among those with LUTS, 128 (67.0%) men and 230

(66.1%) women reported having nocturia twice or more per night. The median

number of nocturia episodes increased with age (men, r=0.510;

P<0.001; women, r=0.418; P<0.001).

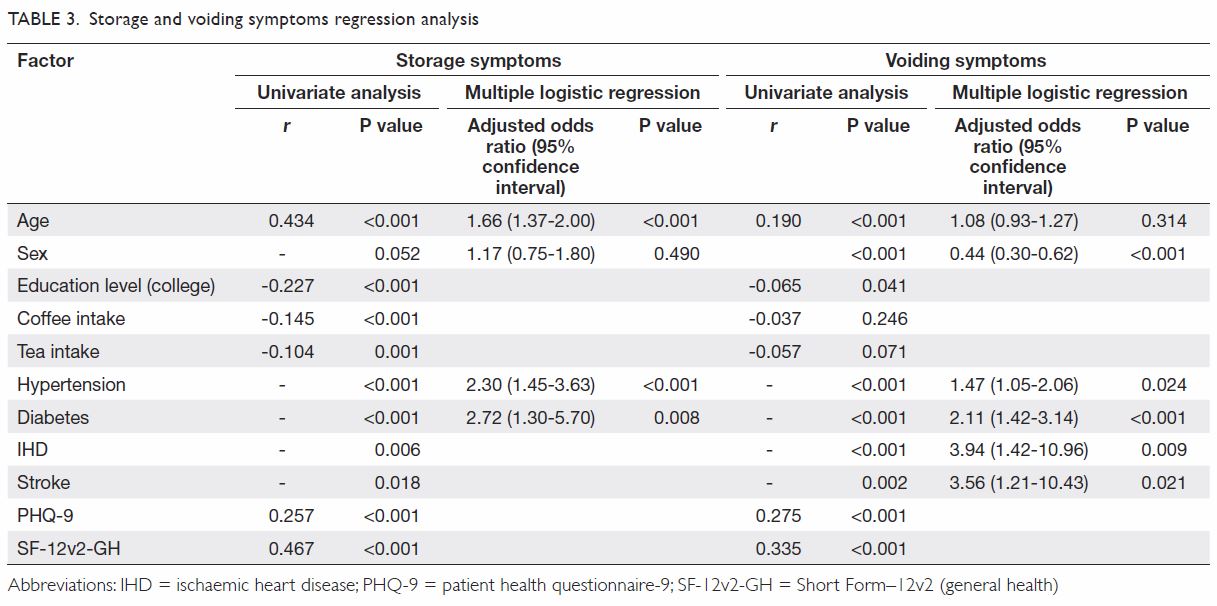

Table 1 includes the general health status and

mental health status of the respondents by means of SF-12v2 score and PHQ

score, respectively. As shown in Table 3, both PHQ-9 scores and SF-12v2 scores were

found to be correlated with both storage symptoms and voiding symptoms.

The higher the PHQ-9 score—indicating more prominent depressive

symptoms—the more significant the LUTS. Similarly, in the SF-12v2

assessment of general health, the higher the score—indicating poorer

health—the more significant LUTS. Storage symptoms and voiding symptoms

were found to be negatively correlated with all components of the SF-12v2.

The results of storage and voiding symptoms

regression analysis are shown in Table 3. Age, presence of hypertension, and diabetes

were found to be significantly correlated with storage symptoms. In

contrast, male sex, presence of hypertension, diabetes, ischaemic heart

disease, and stroke were found to be significantly positively correlated

with voiding symptoms.

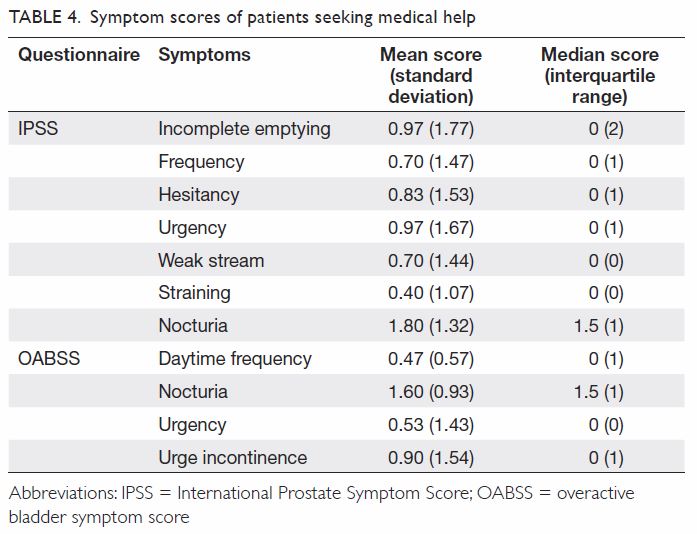

Concerning medical help seeking behaviour among

men, 37.5% of men with severe LUTS, 16.7% with moderate LUTS, and 7.9%

with mild LUTS sought medical help. No women with moderate LUTS sought

medical help. For women with mild LUTS, 2.5% sought medical help. Among

the patients with LUTS who sought medical help, the most prominent

symptoms were nocturia (mean IPSS, 1.80±1.32) and urgency (mean IPSS,

0.97±1.67).

Discussion

In general, LUTS include storage symptoms and

voiding symptoms. Storage symptoms include urinary frequency, nocturia,

urinary urgency, and urinary incontinence. Voiding symptoms include slow

stream, intermittent stream, hesitancy, and straining.10

According to our survey, 77.8% of men and 77.3% of

women aged ≥40 years reported at least mild degree of LUTS according to

IPSS assessment. This prevalence was relatively lower than an internet

survey carried out in mainland China, Taiwan and South Korea, which

reported 86.8% of participants having at least mild symptoms on IPSS.1 However, our findings were comparable to the EpiLUTS

study performed in the US, the United Kingdom and Sweden, which

demonstrated the prevalence of at least one LUTS was 72.3% for men and

76.3% for women.11 In a study of

LUTS in Canada, Germany, Italy, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, Irwin et

al12 reported an even lower

prevalence of LUTS, with an overall prevalence of any LUTS of 62.5% in men

and 66.6% in women. Although such differences in LUTS prevalence across

studies could be attributed to different populations, different cultural

backgrounds or methodological variations could also account for this

observation. Linguistic interpretation discrepancy and different levels of

severity or frequency being used to determine the presence of symptoms

would also generate different results. In addition, changes in general

health awareness and in the socio-economic environment might also effect

survey outcomes. Furthermore, some studies have suggested seasonal

variations of LUTS, with symptoms being more prominent in winter.13 14 Our

survey was carried out in spring and early summer, which could possibly

account for our results falling into the median range in the literature.

Overactive bladder is a subset of storage LUTS,

currently defined by the International Continence Society as urgency, with

or without urgency incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia.10 Our survey included overactive bladder symptom score

as one of the tools to assess the prevalence of storage symptoms in our

population. In the present study, the prevalence of any experience of

urgency was 19.5% for men and 19.1% for women. This is in line with survey

results from Europe, where Milsom et al15

reported the prevalence of overactive bladder symptoms to be 16.6%, and

from the US, where Stewart et al16

reported the prevalence of overactive bladder symptoms to be 16.0% in men

and 16.9% in women. However, for clinically significant overactive bladder

symptoms, urgency must be happening more than once per week. With this

refinement, our study found that 8.6% of men and 5.3% of women reported

urgency more than once per week. This group of patients warrants

urological attention and intervention.

Voiding symptoms that are often associated with

bladder outlet obstruction in men were also found to be common among

women. In accordance with other studies in the literature,1 11 12 our survey confirmed that the prevalence of LUTS

increases with age. In particular, storage symptoms were reported more

often than voiding symptoms (Fig 2). Furthermore, age, hypertension, and diabetes

were found to correlate with storage symptoms on multiple logistic

regression (Table 3). Such observations conform to the findings

by Ng et al,17 who noticed that in

their cohort of 617 men with LUTS, 43% had hypertension and 29% had

dysglycaemia. In addition, Ng et al17

also reported that patients with moderate-to-severe LUTS had a

significantly higher chance of having at least one cardiovascular risk

factor during assessment. These results are echoed in an updated and more

detailed analysis of 966 men with LUTS.18

Yee et al18 demonstrated that the

severity of LUTS was significantly positively correlated with Framingham

score, which is an estimate of the risk of coronary heart disease taking

into account of age, sex, smoking status, cholesterol levels, blood

pressure, and hypertensive treatments. This supports the hypothesis that

atherosclerosis leads to pelvis and bladder ischaemia, and that this might

be one of the mechanisms leading to LUTS.19

Studies on the effect of caffeinated drinks on LUTS

are scarce, and most have been on urinary incontinence. Davis et al20 reported that caffeine consumption was significantly

associated with moderate-to-severe urinary incontinence in men from the US

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. A similar finding was

reported by Baek et al21 from the

Korean National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey among

postmenopausal women. However, our study did not find such a correlation.

On the contrary, the consumption of caffeinated drink correlates

negatively with storage symptoms in general (Table 3). One possible explanation for this

contradiction is that respondents with significant storage symptoms had

usually already cut down their caffeine intake. Thus, our survey could not

illustrate the true impact of caffeinated drinks on overactive bladder

symptoms. In addition to beverage consumption habits, a lower education

level was another factor we found correlating with storage and voiding

symptoms (Table 3). Another study proposed that knowledge on

health and disease perception, which might be a function of education

level, would lower the perceived severity of LUTS.22

In a prospective cohort of elderly men, Chung et al23 showed that the presence of

moderate-to-severe LUTS at baseline was significantly associated with

increased risk for being depressed at 2-year follow-up. The current study

found that, individually, storage symptoms and voiding symptoms were

correlated with a higher PHQ score, translating into a higher risk of

depression. Furthermore, both storage and voiding symptoms were negatively

correlated with all components of general health as measured by SF-12v2.

These findings highlight the importance of LUTS management, considering

its prevalence and its effect on individual well-being.

A significant percentage of respondents with LUTS

did not seek medical help. A similar result has been observed in other

Southeast Asian countries.1

Possible reasons for a low rate of medical help seeking behaviour include

social stigma or a common belief that LUTS is unavoidable with ageing. A

multinational cross-sectional survey on men seeking medical help for LUTS

found that nocturia was the most common symptom among these patients

(88%).24 Our study demonstrated

that, not only was nocturia a common symptom which drove respondents to

seek medical help, it was also the most bothering symptom with the highest

symptom score (Table 4). This suggests that nocturia is one of the

most important symptoms that drive patients to seek medical help. However,

management of nocturia is still a challenge for urologists. Cutting fluid

intake alone was not found to be useful in prolonging the duration between

the time retiring to bed and the first nocturia episode.25 Antidiuretics are presently the only treatment that

provide consistent response in the setting of nocturnal polyuria.26

Limitations of the present study include the bias

from self-reports to measure LUTS, which might be prone to inaccuracy when

compared with physician assessment. However, a meticulous physical

examination would not be possible in the setting of a large-scale

epidemiological study. The telephone interview cam eliminate the

limitation of illiteracy that might be present in self-administered

questionnaires; however, such interviews might introduce bias from each

interviewer’s technique, as well as time pressure on respondents. The

interviewers in our study were professional interviewers with vast

experience in medical research. This minimised potential interview bias.

This population-based survey confirms that LUTS is

common among both men and women. Symptoms increase with age, significantly

affecting patient mental and general health. Storage symptoms are more

prominent than voiding symptoms, with nocturia being the most bothering

symptom. A significant percentage of respondents with LUTS did not seek

medical help. Future research and investigation should address this

deficit.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to

the concept or design of this study; acquisition of data; analysis or

interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; and critical revision for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Joint Chinese

University of Hong Kong-New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research

Ethics Committee (Ref. CRE-2016.588).

References

1. Chapple C, Castro-Diaz D, Chuang YC, et

al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in China, Taiwan, and South

Korea: results from a cross-sectional, population-based study. Adv Ther

2017;34:1953-65. Crossref

2. Hutchison A, Farmer R, Chapple C, et al.

Characteristics of patients presenting with LUTS/BPH in six European

countries. Eur Urol 2006;50:555-61. Crossref

3. Sagnier PP, MacFarlane G, Teillac P,

Botto H, Richard F, Boyle P. Impact of symptoms of prostatism on level of

bother and quality of life of men in the French community. J Urol

1995;153(3 Pt 1):669-73. Crossref

4. Botelho EM, Elstad EA, Taubenberger SP,

Tennstedt SL. Moderating perceptions of bother reports by individuals

experiencing lower urinary tract symptoms. Qual Health Res

2011;21:1229-38. Crossref

5. Wong SY, Hong A, Leung J, Kwok T, Leung

PC, Woo J. Lower urinary tract symptoms and depressive symptoms in elderly

men. J Affect Disord 2006;96:83-8. Crossref

6. Census and Statistics Department, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Available from: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/home/.

Accessed Nov 2016.

7. Homma Y, Yoshida M, Seki N, et al.

Symptom assessment tool for overactive bladder syndrome—overactive bladder

symptom score. Urology 2006;68:318-23. Crossref

8. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The

PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med

2001;16:606-13. Crossref

9. Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh

IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function

(IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction.

Urology 1997;49:822-30. Crossref

10. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al.

The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report

from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence

Society. Urology 2003;61:37-49. Crossref

11. Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, et

al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, the

UK and Sweden: results from the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU

Int 2009;104:352-60. Crossref

12. Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al.

Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and

other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC

study. Eur Urol 2006;50:1306-14. Crossref

13. Kobayashi M, Nukui A, Kamai T.

Seasonal changes in lower urinary tract symptoms in Japanese men with

benign prostatic hyperplasia treated with α1-blockers. Int

Neurourol J 2017;21:197-203. Crossref

14. Choi HC, Kwon JK, Lee JY, Han JH, Jung

HD, Cho KS. Seasonal variation of urinary symptoms in Korean men with

lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia. World J

Mens Health 2015;33:81-7. Crossref

15. Milsom I, Abrams P, Cardozo L, Roberts

RG, Thüroff J, Wein AJ. How widespread are the symptoms of an overactive

bladder and how are they managed? A population-based prevalence study. BJU

Int 2001;87:760-6. Crossref

16. Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW,

et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States.

World J Urol 2003;20:327-36.

17. Ng CF, Wong A, Li ML, Chan SY, Mak SK,

Wong WS. The prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in male patients

who have lower urinary tract symptoms. Hong Kong Med J 2007;13:421-6.

18. Yee CH, Yip JS, Cheng NM, et al. The

cardiovascular risk factors in men with lower urinary tract symptoms.

World J Urol 2018 Aug 6. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

19. McVary K. Lower urinary tract symptoms

and sexual dysfunction: epidemiology and pathophysiology. BJU Int 2006;97

Suppl 2:23-8. Crossref

20. Davis NJ, Vaughan CP, Johnson TM 2nd,

et al. Caffeine intake and its association with urinary incontinence in

United States men: results from National Health and Nutrition Examination

Surveys 2005-2006 and 2007-2008. J Urol 2013;189:2170-4. Crossref

21. Baek JM, Song JY, Lee SJ, et al.

Caffeine intake is associated with urinary incontinence in Korean

postmenopausal women: results from the Korean National Health and

Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS One 2016;11:e0149311. Crossref

22. Yee CH, Li JK, Lam HC, Chan ES, Hou

SS, Ng CF. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in a Chinese

population, and the correlation with uroflowmetry and disease perception.

Int Urol Nephrol 2014;46:703-10. Crossref

23. Chung RY, Leung JC, Chan DC, Woo J,

Wong CK, Wong SY. Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) as a risk factor for

depressive symptoms in elderly men: results from a large prospective study

in Southern Chinese men. PLoS One 2013;8:e76017. Crossref

24. Ho LY, Chu PS, Consigliere DT, et al.

Symptom prevalence, bother, and treatment satisfaction in men with lower

urinary tract symptoms in Southeast Asia: a multinational, cross-sectional

survey. World J Urol 2018;36:79-86. Crossref

25. Teoh JY, Chan C, Ng CA, et al.

Desmopressin oral lyophilisate lessens the burden of nocturia in the

post-TURP men sooner they go asleep—an action unreachable by fluid

restriction alone but attenuated by aging. International Continence

Society 2017 Florence. Available from:

https://www.ics.org/2017/abstract/626. Accessed 11 Mar 2018.

26. Sakalis VI, Karavitakis M,

Bedretdinova D, et al. Medical treatment of nocturia in men with lower

urinary tract symptoms: systematic review by the European Association of

Urology Guidelines Panel for male lower urinary tract symptoms. Eur Urol

2017;72:757-69. Crossref