Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Dec;24(6):579–83 | Epub 19 Nov 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj187227

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Post-fracture care gap: a retrospective

population-based analysis of Hong Kong from 2009 to 2012

MY Cheung, MB, ChB; Angela WH Ho, MB, ChB, FHKAM

(Orthopaedic Surgery); SH Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology,

Caritas Medical Centre, Sham Shui Po, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Angela WH Ho (angelaho@alumni.cuhk.net)

Abstract

Introduction: Patients who

sustain an osteoporotic fracture are at increased risk of sustaining

further osteoporotic fracture. The risk can be reduced by prescription

of anti-osteoporosis medication. The aim of the present study was to

determine the current practice in Hong Kong regarding secondary drug

prevention of fragility fractures after osteoporotic hip fracture.

Methods: Dispensation of

anti-osteoporosis medication records from patients with new fragility

hip fractures aged ≥65 years were retrieved using the Hospital Authority

Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System from 2009 to 2012. The

intervention rate each year was determined from the percentage of

patients receiving anti-osteoporosis medication within 1 year after hip

fracture.

Results: A total of 15 866

patients with osteoporotic hip fracture who met the criteria were

included. The intervention rate differed each year from 2009 to 2012,

ranging between 9% and 15%. Orthopaedic surgeons initiated 63% of

anti-osteoporosis medication, whereas physicians initiated 37%. The

anti-osteoporosis drugs being prescribed included alendronic acid (76%),

ibandronic acid (12%), strontium ranelate (5%), and zoledronic acid

(4%).

Conclusion: Most patients with

hip fracture remained untreated for 1 year after the osteoporotic hip

fracture. The Hospital Authority should allocate more resources to

implement a best practice framework for treatment of patients with hip

fracture at high risk of secondary fracture.

New knowledge added by this study

- Few patients receive anti-osteoporosis medication after hip fracture.

- Implementation of secondary drug prevention of osteoporotic fractures differs among hospitals and specialties.

- The Hong Kong government should allocate more resources for secondary drug prevention of osteoporotic fractures.

- By reducing subsequent fractures, the government can realise substantial cost-savings.

Introduction

There are increasing numbers of geriatric hip

fractures among the ageing population in Hong Kong.1 Patients who sustain an osteoporotic fracture are at

increased risk of sustaining further osteoporotic fractures.2 3 The

cumulative incidence of second hip fracture was 5.1% at 2 years and 8.6%

at 8 years.4 This situation can be

improved by implementing better guidelines for secondary drug prevention

of fragility fractures. Appropriate treatment of patients with fragility

fractures has been shown to reduce subsequent risk of fragility fracture

by up to 50%.5 6 7

Many countries in the world have well-established

guidelines to close this post-fracture care gap. However, this problem has

been overlooked in Hong Kong and the situation is not improving. Diagnosis

and treatment of osteoporosis differs among hospitals and specialties.

There are no standardised guidelines for treating this particular group of

elderly patients. The aim of the present study was to determine the

current practice in Hong Kong regarding secondary drug prevention of

fragility fractures after osteoporotic hip fracture, in order to make

recommendations to implement better guidelines.

Methods

In Hong Kong, about 98% of all hospital admissions

for hip fracture were admitted to public hospitals rather than private

hospitals.8 Patient records from

2009 to 2012, including data on the dispensation of anti-osteoporosis

medication to patients aged ≥65 years with new fragility hip fractures,

were retrieved from the Hospital Authority Clinical Data Analysis and

Reporting System. Patients with hip fracture were identified using

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical

Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 81.52, 81.51, 81.40, 79.15, 79.35, or 78.55

under subdivision Operation Theatre Management System–linked diagnosis.

Patients who took anti-osteoporosis medication before the fracture and

those with pathological fractures were excluded. For the remaining

patients who were eligible for secondary drug prevention, we determined

the intervention rate each year by determining the percentage of patients

receiving anti-osteoporosis medication within 1 year after hip fracture.

Version 4 of the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in

epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for cross-sectional studies was used in

the preparation of this manuscript.

Results

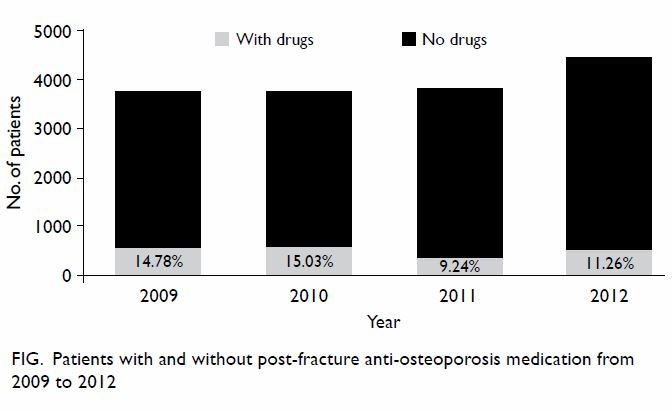

A total of 15 866 patients with osteoporotic hip

fracture who met the criteria were included. From records on

anti-osteoporosis medicine initiation, the intervention rate between 2009

and 2012 was found to be different each year, from as low as 9% in 2010

and as high as 15% in 2009 (Fig). The prescription rate for anti-osteoporosis

medication was 14.78% in 2009, 25.03% in 2010, 9.24% in 2011, and 11.26%

in 2012. Among the specialties prescribing anti-osteoporosis medication,

orthopaedic surgeons initiated 63% of the prescriptions, whereas

physicians initiated 37%. The anti-osteoporosis drugs prescribed in

descending order were alendronic acid (76%), ibandronic acid (12%),

strontium ranelate (5%), zoledronic acid (4%), risedronic acid (1%),

teriparatide (1%), and denosumab (1%). The rate of anti-osteoporosis

medication prescription was between 7% and 31% among the seven public

acute hospitals with orthopaedic emergency admission included in the

study.

Discussion

A 2015 study of geriatric hip fractures showed that

there had been a steady increase in the incidence of geriatric hip

fracture in Hong Kong.1 The

worldwide incidence of geriatric hip fractures is also projected to

increase.9 We expect to see more

patients with fragility fractures in our daily practice with the growing

ageing population.

Patients with geriatric hip fracture carry a high

mortality rate; the overall 30-day mortality is 3.01% and 1-year mortality

is 18.56%.1 Older age and male sex are associated with an increase in

mortality and a higher excess mortality rate following surgery.1 Patients with a second episode of hip fracture have

been found to have an even higher mortality rate.4

By initiating anti-osteoporosis medication, those subsequent fragility

fractures could be prevented.

The British Orthopaedic Association sets standards

for surgeons to comply with in order to improve the quality and outcomes

of care and also to reduce costs.2

Bone health management includes calcium and vitamin D supplement,

osteoporosis treatment, and bone densitometry measurement. According to

the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research Task Force 2012,

patients with hip fracture should receive pharmacological treatment to

prevent additional fractures, because they are clearly at risk for

recurrent hip or other osteoporotic fractures, and initiation of

bisphosphonate therapy after hip fracture has been shown to reduce the

risk of a second hip fracture.10

The main limitation of the present study was that

the data were mainly retrieved from a database of patient records. The

accuracy of these records depends on the correct entry by clinicians of

the diagnosis of hip fracture. Another limitation is that the government

drug dispensation record does not included data from patients who choose

to receive anti-osteoporosis medication in the private sector. This may

create an underestimation of the treatment rate.

Although the treatment rate may have been

underestimated in the present study, worldwide rates of osteoporosis

treatment after hip fracture have been reported to be as low as 10% to 20%

within 1 year.11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 A recent study in Hong Kong showed that 33% of

patients with hip fracture were prescribed medication for osteoporosis in

the 6 months after discharge from the hospital.21

There are also wide discrepancies in drug prescription rates among

different hospitals.

There are several potential reasons for these

differences in drug prescription rates among hospitals. Firstly, different

hospitals follow different working guidelines for the treatment of

osteoporosis after hip fracture. Without standardisation of the

guidelines, there can be a lack of clarity regarding the responsibility to

undertake this care. Siris et al14

found that some physicians did not realise the significance of the

initiation of anti-osteoporosis medication after fragility fractures,

causing underdiagnosis and undertreatment of osteoporosis. Secondly, some

clinicians refer patients to physicians for initiating osteoporosis

treatment; especially in centres without geriatric support, these

follow-up appointments with physicians can be up to 1 year after discharge

from the hospital. Thirdly, many geriatric patients may have renal failure

and may be contra-indicated for certain first-line anti-osteoporosis

medication such as bisphosphonates. They may be unable to afford other

more expensive self-financed anti-osteoporosis medication. Other factors

that affect prescription rates include concerns about medication, and the

available time and funds for diagnosis and treatment.13

The prevalence of femoral neck osteoporosis based

on hip T-score of less than -2.5 was 47.8% in men and 59.1% in women in a

Hong Kong study of 239 geriatric hip fractures.21

In the present study, the intervention rate each year was found to be only

9% to 15% across 2009 to 2012. There is obviously still a huge

post-fracture gap in secondary prevention. Many patients with fragility

fracture do not receive osteoporosis treatment for >1 year after hip

fracture. Furthermore, there was little to no improvement in the

prescription rates among the 4 years studied. Huge improvements could be

achieved by raising the awareness of secondary drug prevention of

osteoporosis and increasing the motivation of physicians.

Improvements can only be achieved with involvement

of both the government and the individual specialties. The government

should allocate more resources and implement a best practice framework for

patients with hip fracture at high risk of secondary fracture. The

government should also subsidise more anti-osteoporosis medications, so

that better treatment can be provided in complicated and severe cases.

Because the treatment of osteoporosis differs among hospitals and

specialties, a fragility fracture committee or a fracture liaison service

can coordinate and standardise patient care by setting up and implementing

an easy-to-follow protocol. More education on the treatment of

osteoporosis should be provided for orthopaedic and medical departments,

to raise awareness and update the relevant knowledge in anti-osteoporosis

medication advancement. In some complicated cases of osteoporosis, the

involvement of different specialties is essential. The formation of

geriatric-orthopaedic working groups and their early involvement in the

perioperative and postoperative period can help ensure that optimal care

is provided to all patients. Even with anti-osteoporosis medication, a

good rehabilitation programme with fall prevention is required; this

should be set up in collaboration with allied health professionals. With

cooperation between the government and different hospital specialties,

more secondary fragility fractures can be prevented. Patients will benefit

from prevention of the morbidity and mortality associated with secondary

fragility fracture.

Recently there has been debate on osteoporosis

treatment and atypical femur fractures. Modi et al22 report that adherence to oral bisphosphonates is low,

estimating that, of patients who are prescribed oral bisphosphonates,

fewer than 40% are still taking them after 1 year. Although atypical femur

fractures have been reported at very low frequencies, not only with

bisphosphonate use but also following treatment with denosumab,23 patients are becoming increasingly reluctant to take

anti-osteoporosis medication. An analysis of three randomised controlled

trials of bisphosphonates concluded that treating 1000 women with

osteoporosis for 3 years with a bisphosphonate will prevent approximately

100 vertebral or non-vertebral fractures (number needed to treat: 10).24 Importantly, for the 100 fractures prevented,

bisphosphonates might cause 0.02 to 1.25 atypical femur fractures,

assuming the relative risk ranges from 1.2 to 11.8 (number needed to harm:

800 to 43 300).25 Hence the

beneficial effect of osteoporosis treatment still outweighs the risk for

atypical femur fracture.

In Hong Kong, about 98% of all hospital admissions

for hip fracture were admitted to public hospitals rather than private

hospitals.8 Public hospitals in

Hong Kong face a huge financial burden and lack of health care resources

for providing optimal care to the ageing population. The cost associated

with the prescription of anti-osteoporosis medication is of concern of the

government. However, the tremendous hospital expenditure related to hip

fracture care can be easily overlooked. In Hong Kong, the direct medical

cost for each hip fracture was US$8831.9 in 2018, with the projected

direct cost of US$84.7 million in total.26

In 2014, 84% of the drugs prescribed for osteoporosis were

bisphosphonates.27 The annual cost

of prescription of bisphosphonates per patient was approximately HK$174.

Although multiple patients must be treated to prevent a single fracture,

reducing the number of subsequent osteoporotic fractures can help the

government to achieve significant cost-savings.

Despite the numerous benefits of anti-osteoporosis

medication for patients with fragility fractures, the prescription rate

remains low not only in Hong Kong, but also in the other parts of the

world. Physicians should be aware of the benefits of anti-osteoporosis

medication for patients with fragility fractures and guidelines for

osteoporosis treatment should be developed and used more widely.

Conclusion

There is a large post-fracture care gap in

secondary drug prevention for patients with osteoporotic hip fracture in

Hong Kong. The majority of the patients are neither diagnosed nor tested

for osteoporosis. Most remained untreated for 1 year after the

osteoporotic hip fracture. The Hong Kong Hospital Authority needs to

allocate more resources to implement a best practice framework for

patients with hip fracture at high risk of secondary fracture, so that

they receive appropriate anti-osteoporosis medication. By reducing the

number of subsequent osteoporotic fractures, the Hospital Authority can

realise substantial cost-savings.

Author contributions

Concept and design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: MY Cheung, AWH Ho.

Analysis or interpretation of data: MY Cheung, AWH Ho.

Drafting of the article: MY Cheung, AWH Ho.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: MY Cheung, AWH Ho.

Acquisition of data: MY Cheung, AWH Ho.

Analysis or interpretation of data: MY Cheung, AWH Ho.

Drafting of the article: MY Cheung, AWH Ho.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: MY Cheung, AWH Ho.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility

for its accuracy and integrity. An earlier version of this paper was

presented as a poster at the Annual Congress of the Hong Kong Orthopaedic

Association, 6 to 8 November 2015, Hong Kong; at the World Congress on

Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases, 26 to 29 March

2015, Milan, Italy; and at the 15th Regional Osteoporosis Conference, 24

to 25 May 2014, Hong Kong.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Man LP, Ho AW, Wong SH. Excess mortality

for operated geriatric hip fracture in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J

2016;22:6-10. Crossref

2. British Orthopaedic Association. The

Care of Patients with Fragility Fracture. London: British Orthopaedic

Association; 2007.

3. Johnell O, Kanis JA, Odén A, et al.

Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int

2004;15:175-9. Crossref

4. Lee YK, Ha YC, Yoon BH, Koo KH.

Incidence of second hip fracture and compliant use of bisphosphonate.

Osteoporos Int 2013;24:2099-104. Crossref

5. Lyles KW, Colón-Emeric CS, Magaziner JS,

et al. Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip

fracture. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1799-809. Crossref

6. Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, et al.

Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures

in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial.

Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA

1999;282:1344-52. Crossref

7. Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, et al.

Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women

with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research

Group. Lancet 1996;348:1535-41. Crossref

8. Chau PH, Wong M, Lee A, Ling M, Woo J.

Trends in hip fracture incidence and mortality in Chinese population from

Hong Kong 2001-09. Age Ageing 2013;42:229-33. Crossref

9. Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA.

World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 1997;7:407-13. Crossref

10. Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R, et al.

Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force on secondary

fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res 2012;27:2039-46. Crossref

11. Andrade SE, Majumdar SR, Chan KA et

al. Low frequency of treatment of osteoporosis among postmenopausal women

following a fracture. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2052-7. Crossref

12. Feldstein A, Elmer PJ, Orwoll E,

Herson M, Hillier T. Bone mineral density measurement and treatment for

osteoporosis in older individuals with fractures: a gap in evidence-based

practice guideline implementation. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2165-72. Crossref

13. Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER, Jamal SA,

Beaton DE. Practice patterns in the diagnosis and treatment of

osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: a systematic review. Osteoporos

Int 2004;15:767-78. Crossref

14. Siris ES, Bilezikian JP, Rubin MR, et

al. Pins and plaster aren’t enough: a call for the evaluation and

treatment of patients with osteoporotic fractures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

2003;88:3482-6. Crossref

15. Kamel HK, Hussain MS, Tariq S, Perry

HM, Morley JE. Failure to diagnose and treat osteoporosis in elderly

patients hospitalized with hip fracture. Am J Med 2000;109:326-9. Crossref

16. Torgerson DJ, Dolan P. Prescribing by

general practitioners after an osteoporotic fracture. Ann Rheum Dis

1998;57:378-9. Crossref

17. Follin SL, Black JN, McDermott MT.

Lack of diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in men and women after hip

fracture. Pharmacotherapy 2003;23:190-8. Crossref

18. Juby AG, De Geus-Wenceslau CM.

Evaluation of osteoporosis treatment in seniors after hip fracture.

Osteoporos Int 2002;13:205-10. Crossref

19. Harrington JT, Broy SB, Derosa AM,

Licata AA, Shewmon DA. Hip fracture patients are not treated for

osteoporosis: a call to action. Arthritis Rheum 2002;47:651-4. Crossref

20. Gardner MJ, Brophy RH, Demetrakopoulos

D, et al. Interventions to improve osteoporosis treatment following hip

fracture. A prospective randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am

2005;87:3-7. Crossref

21. Ho AW, Lee MM, Chan EW, et al.

Prevalence of pre-sarcopenia and sarcopenia in Hong Kong Chinese geriatric

patients with hip fracture and its correlation with different factors.

Hong Kong Med J 2016;22:23-9. Crossref

22. Modi A, Siris ES, Tang J, Sen S. Cost

and consequences of noncompliance with osteoporosis treatment among women

initiating therapy. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:757-65. Crossref

23. Selga J, Nuñez JH, Minguell J, Lalanca

M, Garrido M. Simultaneous bilateral atypical femoral fracture in a

patient receiving denosumab: case report and literature review. Osteoporos

Int 2016;27:827-32. Crossref

24. Black DM, Kelly MP, Genant HK, et al.

Bisphosphonates and fractures of the subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femur.

N Engl J Med 2010;362:1761-71. Crossref

25. Black DM, Rosen CJ. Clinical practice.

Postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2016;374:254-62. Crossref

26. Cheung CL, Ang SB, Chadha M, et al. An

updated hip fracture projection in Asia: The Asian Federation of

Osteoporosis Societies study. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 2018;4:16-21. Crossref

27. Ho KC, Tsoi MF, Cheung TT, Cheung CL,

Cheung BM. Increase in prescriptions for osteoporosis and reduction in hip

fracture incidence in Hong Kong during 2005-2014. Hong Kong Med J

2016;22(Suppl 1):25S.