DOI: 10.12809/hkmj177024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE CME

Medication overuse headache: strategies for prevention

and treatment using a multidisciplinary approach

M van Driel, MD, PhD1; E Anderson, MSc,

PhD2; T McGuire, BPharm, PhD3,4,5; R Stark, MB, BS,

FRACP6

1 Faculty of Medicine, University of

Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

2 In Vivo Academy Ltd, In Vivo

Communications, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

3 Faculty of Health Sciences and

Medicine, Bond University, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia

4 School of Pharmacy, The University of

Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

5 Mater Pharmacy Services, Mater Health

Services, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

6 Neurology Department, Alfred Hospital,

Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Corresponding author: Prof M van Driel (m.vandriel@uq.edu.au)

Abstract

Medication overuse headache, which affects

patients who have migraines and frequent headaches, is prevalent

worldwide and can severely impact daily functioning. Medication overuse

headache is often not recognised by primary care physicians or general

practitioners, as patients may overuse medications that are freely

available without a prescription. Overuse of codeine-containing

analgesics is particularly problematic and contributes to ongoing

morbidity and opioid-related mortality. This article aims to provide an

overview of the detection, prevention, and management of medication

overuse headache. The definition of medication overuse headache and the

risk levels of commonly used symptomatic headache medications are

presented. An algorithm consisting of a number of simple questions can

assist general practitioners with identifying at-risk patients.

Treatment strategies are discussed in the context of a multidisciplinary

approach.

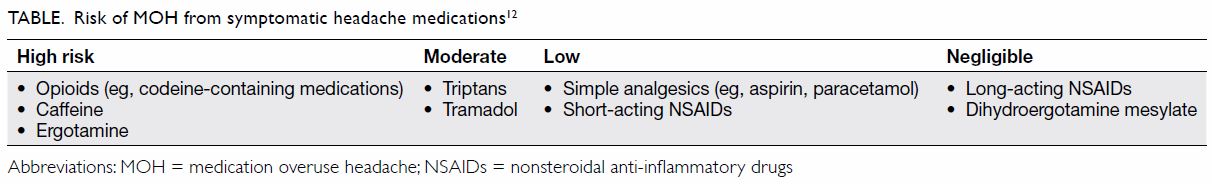

The estimated prevalence of medication overuse

headache (MOH) in the general population ranges from 0.6% to 7%.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A number of

acute headache treatments may cause MOH,7

and the medications that are predominantly associated with MOH vary from

country to country.1 7 9 10 Opioids such as codeine are particularly problematic,

as they are consistently associated with increasingly severe headaches11 (Table12) and

poor outcomes after withdrawal.13

In a number of regions, including Hong Kong and Japan, codeine-containing

medication is only available by prescription.14

In Australia, beginning in 2018, codeine (and its combinations with simple

analgesics) will only be available by prescription, following a 2015

decision by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).15 This policy change is supported by evidence

demonstrating an increase in unintentional codeine-related deaths in

Australia.16

A systematic analysis of the global, regional, and

national burden of neurological disorders from 1990 to 2015 (using data

from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015) found that neurological

disorders were the leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)

in 2015, with the most prevalent neurological disorders being tension-type

headache (1505.9 million DALYs), migraine (958.8 million DALYs), and MOH

(58.5 million DALYs).17 As large

numbers of people are potentially at risk of MOH, including anyone with

frequent primary episodic headaches, strategies for primary prevention,

treatment, and prevention of relapse may have substantial public health

benefits.

Definition of medication overuse headache

The definition of MOH is headache occurring on ≥15

days per month as a consequence of regular overuse of acute or symptomatic

headache medication (≥10 days per month for triptans, ergotamines, or

opioids; ≥15 days per month for simple or combined analgesics) for more

than 3 months. It usually, but not invariably, resolves after the overuse

is stopped.18

Problems with detection and treatment of medication

overuse headache

Patients’ lack of awareness of medication overuse

as a cause of headaches, reluctance to acknowledge how much medication

they take, and poor adherence to recommended treatment have been

identified as barriers to detection and management of MOH. A survey of

Australian general practitioners (GPs)19

showed that GPs’ awareness of MOH is low, although the awareness of

codeine overuse in general may have increased following the TGA’s

decision, which was widely discussed in the media. In Singapore, a general

practice survey of patients and their attending physicians in a primary

care setting found that 22.6% of the patient population reported taking

acute pain medication for headaches at least 4 days per week. However, the

physicians only identified this in 5.3% of the study population,

indicating that physicians did not recognise a large percentage of

patients at risk of MOH.20 Khu et

al20 commented that overuse of

analgesic medications may lead to ‘doctor-hopping’ by patients in search

of increasingly elusive headache relief. There may be a need to provide

greater awareness of MOH during medical training, as a survey of final

year medical students in Singapore found that 47% were unfamiliar with MOH

as a disease entity, and 96% were unfamiliar with local clinical practice

guidelines about headaches.21

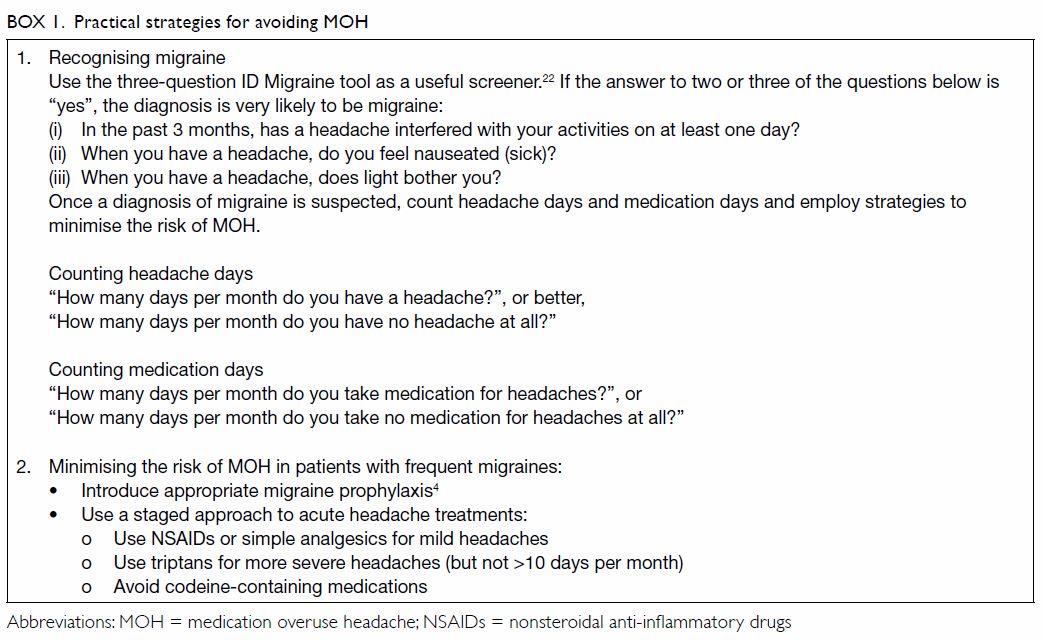

Patients with frequent episodic migraines

(headaches on 8-15 days per month) or chronic migraines (headaches on

>15 days per month) are at particular risk of developing MOH. General

practitioners play a crucial role in identifying these patients, assessing

their medication intake, and offering strategies to minimise the risk of

MOH (Box 14 22).

Patients may be reluctant to reveal how many

analgesics they take or may be unaware or unwilling to accept that the

medication they use to treat their headaches is actually contributing to

the continuation of their headaches. They may also be reluctant to

discontinue medication that they have found to provide some relief for

their headaches in the past. Patients who are anxious about their

headaches interfering with essential activities, such as work, may use

medication routinely as a preventive measure. In addition, a common

misperception among consumers is that medication that can be purchased

without a prescription (‘over the counter’) is harmless.23 Unfortunately, once established, MOH (particularly

that caused by opioids) has a high relapse rate after treatment.24 Adherence to recommended treatment is generally

suboptimal in patients with MOH, but the majority of relapses occur in the

first year after withdrawal.25 It

is therefore important to educate patients about the pathophysiology and

treatment of MOH and to continue supporting them beyond the immediate

period of withdrawal.

Some patients who report “excessive” medication use

and very frequent headache do not respond to medication withdrawal.

Patients who develop MOH are usually those with intrinsically

high-frequency headaches, and withdrawal tends to lead to reversion to

their natural background headache pattern, which may range from infrequent

episodic migraines to higher-frequency patterns. Scher et al26 questioned the benefit of withdrawal or restriction

of medication on the grounds that the patient may not benefit from it.

However, withdrawal allows the underlying headache pattern to be

determined and a reappraisal of headache control to be conducted. Study

results have demonstrated that withdrawal of headache medication benefits

many patients with MOH. For example, in a recent study, patients diagnosed

with MOH were randomised to 2 months’ detoxification with either complete

withdrawal of medication or acute medication restricted to 2 days/week.

The number of migraine-days/ month was significantly reduced after 6

months with both treatments, with a greater reduction of

migraine-days/month in the complete withdrawal group, indicating that

complete withdrawal is generally more effective than medication

restriction and that medication overuse was a major factor in the

patients’ headache pathology.27

A multidisciplinary approach

As patients with MOH often do not present to their

GPs in response to the first instance, pharmacists can play a role in

educating patients who self-medicate with analgesics when analgesics are

purchased without a prescription.28

They could encourage patients who may be overusing pain relief medication

to consult their GPs to discuss other treatment options. However, it may

not be easy to identify at-risk patients, as some obtain large quantities

of headache medications by shopping at different pharmacies.

Identification of these patients could be facilitated by using a tracking

system to detect patients who buy headache medication at multiple

pharmacies.

Conditions associated with self-medication, such as

MOH, could be prevented by community pharmacists. Community pharmacists

have overviews of both prescriptions and non-prescription medications that

patients are taking (provided that patients are not visiting several

different pharmacies) and are easily accessible to patients.29 30 Thus, the

sale of headache medications is an opportunity to discuss their potential

adverse effects and their role in MOH. A survey in Japan on the role of

community pharmacists in self-medication of patients with headache found

that 32% of the surveyed doctors were concerned about the increase of

patients who overuse headache medication. Both doctors and pharmacists

thought that pharmacists should not only provide patients with

“instruction on the use of drugs” but also suggest “when to consult a

hospital or clinic”.31 However,

strategies may need to be devised to motivate patients to do this, as

another Japanese survey of pharmacists and doctors found that 22% of

pharmacists had experienced refusal by patients with headache to consult a

clinic, despite the pharmacist’s recommendation.32

Community pharmacists have an important role in

supporting patients with headache. This can be fostered by all key

stakeholders—pharmacists, doctors, and patients—being provided with

multidisciplinary opportunities to improve their MOH health literacy and

to maintain an open and collaborative relationship.

Although MOH often develops outside of GPs’

immediate view through patients’ self-medication, GPs are important in its

prevention, detection, and treatment. The first step is educating

patients, and when they do not understand the cause of and treatment for

MOH, taking time to inform them and clarify their misunderstandings.29 The next step is to develop a plan with the patient

and provide clear and continuing support for what is often a challenging

journey. General practitioners also need to be aware of situations in

which patients should be referred to a neurologist, preferably one who

specialises in headache management.

Discussions between GPs or pharmacists and patients

who overuse headache medication are often delicate. The patient may

perceive an accusation of ‘recreational use’ of (particularly

codeine-containing) drugs. It is vital for productive communication that

the health care professional clarify that there is no suspicion of this

type and that the medications are recognised as being used to deal with

genuinely troublesome symptoms. It is vital to subsequently emphasise that

ongoing use of particular headache medications may contribute to

perpetuation of headaches and that better strategies are available.

Management and prevention strategies

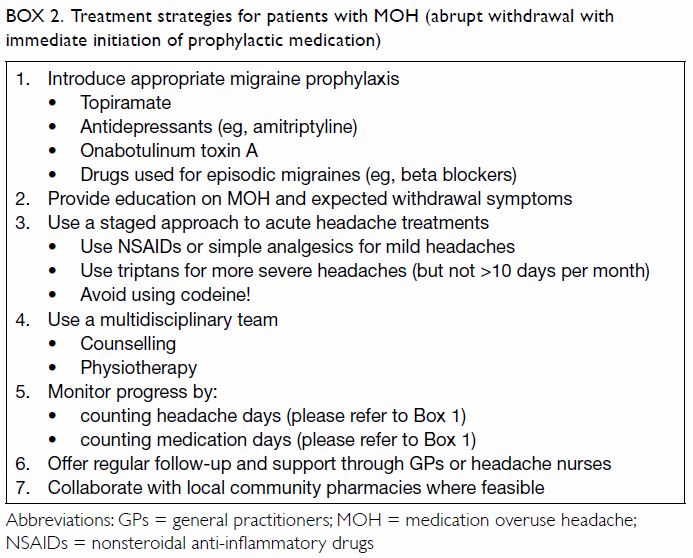

Prevention of headaches is better than curing them.

Pharmacists and GPs who are aware of MOH can detect patients with

increasing frequencies of headaches and medication use. Strategies to

assist such patients before they progress into frank MOH include lifestyle

adjustments and appropriate prophylaxis, as discussed below as part of MOH

treatment (Box 2).

Box 2. Treatment strategies for patients with MOH (abrupt withdrawal with immediate initiation of prophylactic medication)

Complete withdrawal from overused headache

medications is a key component of the management strategy, along with

education, counselling, and support. Abrupt withdrawal is usually

preferred, but tapered withdrawal may be more appropriate when codeine is

implicated.25 Coexisting

psychiatric conditions should also be assessed and managed. As medication

discontinuation results in withdrawal headaches—often associated with

nausea, vomiting, and sleep disturbance—patients frequently need

assistance coping with withdrawal symptoms and persevering with

discontinuation.4 12 33 34 Symptoms usually last between 2 and 10 days, with

withdrawal from triptans lasting approximately 4 days and that from

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs lasting about 10 days. Withdrawal can

be managed through primary care; however, opioid discontinuation may

require hospitalisation.34 35

Accurate diagnosis based on the third edition of

the International Classification of Headache Disorders17 and referral of complex cases to a

neurologist/headache specialist is recommended for individualised

treatments. Psychiatric assessment may also be indicated in some cases.

However, in many countries, limited specialist availability means that

referrals need to be selective. Psychologists and physical therapists have

a role, as psychotherapy, relaxation techniques, physical exercise, and

cognitive behaviour therapy may be useful adjuncts to supervised

pharmacotherapy.4 12 23 28 34 36 37 The

combination of behavioural treatment and prophylactic medication may

significantly reduce the risk of relapse.37

Preventive medications for chronic migraines include antiepileptic drugs

(particularly topiramate), antidepressants (eg, amitriptyline),

onabotulinum toxin A, and drugs used for episodic migraines (eg, beta

blockers). For example, topiramate (oral) and onabotulinum toxin A (by

local injection) are recommended by the Taiwan Headache Society 2017

medical treatment guidelines as first-line treatments for prophylaxis of

chronic migraines.38 Education

about acute and prophylactic treatment may improve adherence to both

pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies.28

In some circumstances, withdrawal may require

hospital admission. Patients with MOH who have been detoxified as

in-patients should be followed up by their GPs. Support by a headache

nurse (available in some neurological practices) can improve adherence to

detoxification.39

Multidisciplinary treatment of patients with MOH,

including pharmacological prophylaxis, relaxation therapy, and aerobic

sports, is associated with reduction in headaches, as long as patients

adhere to the recommended therapies.28

Motivational telephone interviewing may also help to promote adherence.40 To supplement regular GP

support, practice nurses could be involved in patient support, and they

could liaise with pharmacists to monitor medication use.

Conclusion

There is an urgent need for increased awareness of

MOH among both patients and health care professionals.41 Medication overuse headache causes considerable

morbidity but is preventable. Headache frequency (and the associated

disability, depression, and anxiety) can be considerably reduced in

patients with MOH through withdrawal from the overused medication and

appropriate supportive treatment. A multidisciplinary approach involving

primary care physicians (GPs), community pharmacists, nurses, and allied

health providers,36 with referral

to neurologists/headache specialists (where available) for complex cases,

is recommended.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept of the

paper, acquisition and interpretation of data and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. EA and MVD drafted the

article. All authors approved the final version.

Declaration

M van Driel, T McGuire, and R Stark have received

consulting fees from In Vivo Academy Ltd for development of education

materials for a multidisciplinary programme about MOH. In Vivo Academy Ltd

received an unrestricted educational grant from Pfizer to develop

educational material about MOH. R Stark has also received lecture and/or

consulting fees from Allergan, Novartis, TEVA, MSD, Abbvie and SciGen

(Australia) and from In Vivo Academy Ltd relating to a Pfizer-sponsored

project, and has undertaken clinical trials for Allergan. E Anderson is an

employee of In Vivo Academy Ltd.

References

1. Cha MJ, Moon HS, Sohn JH, et al. Chronic

daily headache and medication overuse headache in first-visit headache

patients in Korea: a multicenter clinic-based study. J Clin Neurol

2016;12:316-22. Crossref

2. Cheung V, Amoozegar F, Dilli E.

Medication overuse headache. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2015;15:509. Crossref

3. Herekar AA, Ahmad A, Uqaili UL, et al.

Primary headache disorders in the adult general population of Pakistan—a

cross sectional nationwide prevalence survey. J Headache Pain 2017;18:28.

Crossref

4. Kristoffersen ES, Lundqvist C.

Medication-overuse headache: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Ther

Adv Drug Saf 2014;5:87-99. Crossref

5. Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Katsarava Z, et

al. The impact of headache in Europe: principal results of the Eurolight

project. J Headache Pain 2014;15:31. Crossref

6. Yu S, Liu R, Zhao G, et al. The

prevalence and burden of primary headaches in China: a population-based

door-to-door survey. Headache 2012;52:582-91. Crossref

7. Westergaard ML, Munksgaard SB, Bendtsen

L, Jensen RH. Medication-overuse headache: a perspective review. Ther Adv

Drug Saf 2016;7:147-58. Crossref

8. Zebenholzer K, Andree C, Lechner A, et

al. Prevalence, management and burden of episodic and chronic headaches—a

cross-sectional multicentre study in eight Austrian headache centres. J

Headache Pain 2015;16:531. Crossref

9. Dong Z, Chen X, Steiner TJ, et al.

Medication-overuse headache in China: clinical profile, and an evaluation

of the ICHD-3 beta diagnostic criteria. Cephalalgia 2015;35:644-51. Crossref

10. Manandhar K, Risal A, Steiner TJ,

Holen A, Linde M. The prevalence of primary headache disorders in Nepal: a

nationwide population-based study. J Headache Pain 2015;16:95. Crossref

11. Johnson JL, Hutchinson MR, Williams

DB, Rolan P. Medication-overuse headache and opioid-induced hyperalgesia:

A review of mechanisms, a neuroimmune hypothesis and a novel approach to

treatment. Cephalalgia 2013;33:52-64. Crossref

12. Smith TR, Stoneman J. Medication

overuse headache from antimigraine therapy: clinical features,

pathogenesis and management. Drugs 2004;64:2503-14. Crossref

13. Bøe MG, Salvesen R, Mygland A. Chronic

daily headache with medication overuse: predictors of outcome 1 year after

withdrawal therapy. Eur J Neurol 2009;16:705-12. Crossref

14. Butler J. You won’t be able to buy

codeine over the counter anymore. Huffington Post 2016 Dec 20. Available

from:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/2016/12/19/you-wont-be-able-to-buy-codeine-over-the-counteranymore_a_21631170/.

Accessed 25 Oct 2018.

15. Therapeutic Goods Administration,

Department of Health, Australian Government. Proposal for the

re-scheduling of codeine products. 2015. Available from:

https://www.tga.gov.au/media-release/proposal-re-scheduling-codeineproducts.

Accessed 2 Mar 2017.

16. Roxburgh A, Hall WD, Burns L, et al.

Trends and characteristics of accidental and intentional codeine overdose

deaths in Australia. Med J Aust 2015;203:299. Crossref

17. GBD 2015 Neurological Disorders

Collaborator Group. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological

disorders during 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of

Disease Study 2015. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:877-97. Crossref

18. Headache Classification Committee of

the International Headache Society. The International Classification of

Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia

2013;33:629-808. Crossref

19. van Driel ML, McGuire TM, Stark R,

Lazure P, Garcia T, Sullivan L. Learnings and challenges to deploy an

interprofessional and independent medical education programme to a new

audience. J Eur CME 2017;6:1400857. Crossref

20. Khu JV, Siow HC, Ho KH. Headache

diagnosis, management and morbidity in the Singapore primary care setting:

findings from a general practice survey. Singapore Med J 2008;49:774-9.

21. Ong JJ, Chan YC. Medical undergraduate

survey on headache education in Singapore: knowledge, perceptions, and

assessment of unmet needs. Headache 2017;57:967-78. Crossref

22. Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, et

al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: The ID

MigraineTM validation study. Neurology 2003;61:375-82. Crossref

23. Frich JC, Kristoffersen ES, Lundqvist

C. GPs’ experiences with brief intervention for medication-overuse

headache: a qualitative study in general practice. Br J Gen Pract

2014;64:e525-31. Crossref

24. Katsarava Z, Muessig M, Dzagnidze A,

Fritsche G, Diener HC, Limmroth V. Medication overuse headache: rates and

predictors for relapse in a 4-year prospective study. Cephalalgia

2005;25:12-5. Crossref

25. Evers S, Marziniak M. Clinical

features, pathophysiology, and treatment of medication-overuse headache.

Lancet Neurol 2010;9:391-401. Crossref

26. Scher AI, Rizzoli PB, Loder EW.

Medication overuse headache: an entrenched idea in need of scrutiny.

Neurology 2017;89:1296-304. Crossref

27. Carlsen LN, Munksgaard SB, Jensen RH,

Bendtsen L. Complete detoxification is the most effective treatment of

medication-overuse headache: a randomized controlled open-label trial.

Cephalalgia 2018;38:225-36. Crossref

28. Gaul C, Brömstrup J, Fritsche G,

Diener HC, Katsarava Z. Evaluating integrated headache care: a one-year

follow-up observational study in patients treated at the Essen headache

centre. BMC Neurol 2011;11:124. Crossref

29. Giaccone M, Baratta F, Allais G, Brusa

P. Prevention, education and information: the role of the community

pharmacist in the management of headaches. Neurol Sci 2014;35(1

Suppl):1-4. Crossref

30. O’Sullivan EM, Sweeney B, Mitten E,

Ryan C. Headache management in community pharmacies. Ir Med J

2016;109:373.

31. Naito Y, Ishii M, Kawana K, Sakairi Y,

Shimizu S, Kiuchi Y. Role of pharmacists in a community pharmacy for

self-medication of patients with headache [in Japanese]. Yakugaku Zasshi

2009;129:735-40. Crossref

32. Naito Y, Ishii M, Sakairi Y, Kawana K,

Shimizu S, Kiuchi Y. Need for collaboration between community pharmacies

and hospitals or clinics in providing medical treatment for patients with

headache [in Japanese]. Yakugaku Zasshi 2009;129:741-8. Crossref

33. Stark R, Hutton E. Chronic migraine

and other types of chronic daily headache. Medicine Today 2013;14:29-35.

34. Kristoffersen ES, Lundqvist C.

Medication-overuse headache: a review. J Pain Res 2014;26:367-78. Crossref

35. Williams D. Medication overuse

headache. Aust Prescr 2005;28:59-62. Crossref

36. Bendtsen L, Munksgaard S, Tassorelli

C, et al. Disability, anxiety and depression associated with

medication-overuse headache can be considerably reduced by detoxification

and prophylactic treatment. Results from a multicentre, multinational

study (COMOESTAS project). Cephalalgia 2014;34:426-33. Crossref

37. Lake AE 3rd. Medication overuse

headache: biobehavioral issues and solutions. Headache 2006;46(3

Suppl):S88-97. Crossref

38. Huang TC, Lai TH, Taiwan Headache

Society TGSOTHS. Medical treatment guidelines for preventive treatment of

migraine. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2017;26:33-53.

39. Pijpers JA, Louter MA, de Bruin ME, et

al. Detoxification in medication-overuse headache, a retrospective

controlled follow-up study: does care by a headache nurse lead to cure?

Cephalalgia 2016;36:122-30. Crossref

40. Stevens J, Hayes J, Pakalnis A. A

randomized trial of telephone-based motivational interviewing for

adolescent chronic headache with medication overuse. Cephalalgia

2014;34:446-54. Crossref

41. Stark R, McGuire T, van Driel M.

Medication overuse headache in Australia: a call for multidisciplinary

efforts at prevention and treatment. Med J Aust 2016;205:283. Crossref