DOI: 10.12809/hkmj177095

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE CME

Recommendations on prevention and screening for

colorectal cancer in Hong Kong

Cancer Expert Working Group on Cancer Prevention

and Screening (August 2016 to July 2018)

TH Lam, MD1; KH Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM

(Medicine)2; Karen KL Chan, MBBChir, FHKAM (Obstetrics and

Gynaecology)3; Miranda CM Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)4;

David VK Chao, FRCGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)5; Annie NY

Cheung, MD, FHKAM (Pathology)6; Cecilia YM Fan, MB, BS, FHKAM

(Family Medicine)7; Judy Ho, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)8;

EP Hui, MD (CUHK), FHKAM (Medicine)9; KO Lam, MB, BS, FHKAM

(Radiology)10; CK Law, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)11;

WL Law, MS, FHKAM (Surgery)12; Herbert HF Loong, MB, BS, FHKAM

(Medicine)13; Roger KC Ngan, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)14;

Thomas HF Tsang, MB, BS, FHKAM (Community Medicine)15; Martin

CS Wong, MD, FHKAM (Family Medicine)16; Rebecca MW Yeung, MD,

FHKAM (Radiology)17; Anthony CH Ying, MB, BS, FHKAM (Radiology)18;

Regina Ching, MB, BS, FHKAM (Community Medicine)19

1 School of Public Health, Li Ka Shing

Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Health, Hong Kong

3 The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians

and Gynaecologists, Hong Kong

4 Hospital Authority (Surgical), Hong

Kong

5 The Hong Kong College of Family

Physicians, Hong Kong

6 The Hong Kong College of Pathologists,

Hong Kong

7 Professional Development and Quality

Assurance, Department of Health, Hong Kong

8 World Cancer Research Fund Hong Kong,

Hong Kong

9 Hong Kong College of Physicians, Hong

Kong

10 Department of Clinical Oncology, The

University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

11 Hong Kong College of Radiologists,

Hong Kong

12 The College of Surgeons of Hong Kong,

Hong Kong

13 Department of Clinical Oncology, The

Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

14 Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital

Authority, Hong Kong

15 Hong Kong College of Community

Medicine, Hong Kong

16 The Jockey Club School of Public

Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

17 Hospital Authority (Non-surgical),

Hong Kong

18 The Hong Kong Anti-Cancer Society,

Hong Kong

19 Centre for Health Protection,

Department of Health, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Regina Ching (regina_ching@dh.gov.hk)

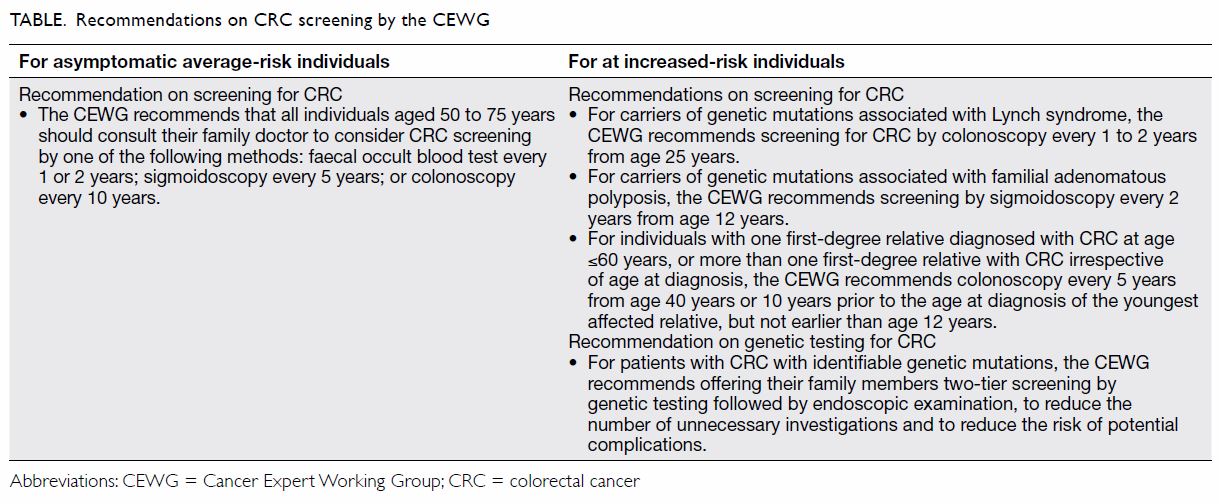

Abstract

Colorectal cancer is the commonest cancer in Hong

Kong. The Cancer Expert Working Group on Cancer Prevention and Screening

was established in 2002 under the Cancer Coordinating Committee to

review local and international scientific evidence, assess and formulate

local recommendations on cancer prevention and screening. At present,

the Cancer Expert Working Group recommends that average-risk individuals

aged 50 to 75 years and without significant family history consult their

doctors to consider screening by: (1) annual or biennial faecal occult

blood test, (2) sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, or (3) colonoscopy every 10

years. Increased-risk individuals with significant family history such

as those with a first-degree relative diagnosed with colorectal cancer

at age ≤60 years; those who have more than one first-degree relative

diagnosed with colorectal cancer irrespective of age at diagnosis; or

carriers of genetic mutations associated with familial adenomatous

polyposis or Lynch syndrome should start colonoscopy screening earlier

in life and repeat it at shorter intervals.

Introduction

In Hong Kong, the Cancer Coordinating Committee is

a high-level committee chaired by the Secretary for Food and Health to

steer the direction of work on prevention and control of cancer. Under the

Cancer Coordinating Committee, the Cancer Expert Working Group (CEWG) on

Cancer Prevention and Screening was established in 2002 to review local

and international scientific evidence and practices with a view to making

recommendations on cancer prevention and screening suitable for Hong Kong.

This article details the local burden and

prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC), and explains the rationale

underpinning the current CEWG recommendations on CRC screening, which were

reaffirmed and updated in 2017.

Local epidemiology

Colorectal cancer is the commonest cancer in Hong

Kong. According to the Hong Kong Cancer Registry, there were 5036 newly

registered CRC cases in 2015, representing 16.6% of all new cancer cases.1 The age-standardised incidence

rates were 41.5 per 100 000 population for men and 26.2 per 100 000

population for women.1 The median

age at diagnosis of CRC was 68 years in men and 70 years in women.1 The age-specific incidence rates increased

significantly from age 50 years. Colorectal cancer is more common in men

with the male-to-female ratio of 1.3:1 for new cases in 2015.1

The Death Registry registered 2089 deaths caused by

CRC in 2016, representing 14.7% of all cancer deaths and ranking it the

second leading cause of cancer deaths in Hong Kong.2 The age-standardised mortality rates were 18.0 per 100

000 population for men and 10.5 per 100 000 population for women.2 After adjusting for the effect of population ageing,

the age-standardised incidence rates for both sexes still showed an upward

trend, whereas the age-standardised mortality rates for both sexes have

remained stable for more than 30 years.2

Risk factors

Risk factors for developing CRC may be modifiable

or non-modifiable. Modifiable risk factors are those that are related to

lifestyle, such as physical inactivity, low fibre intake, consumption of

red meat or processed meat, overweight or obesity, smoking, and alcohol

use. The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on

Cancer classifies consumption of processed meat as “carcinogenic to humans

(Group I),” and consumption of red meat as “probably carcinogenic to

humans (Group 2A)” and indicated that every 50-g portion of processed meat

eaten daily increases the risk of CRC by about 18%.3 Conversely, the risk of CRC is inversely associated

with intake of fibre.4 In addition,

the International Agency for Research on Cancer considered that there is

sufficient evidence to classify alcoholic beverage and tobacco smoking as

carcinogenic to humans in the development of CRC.5

Separately, the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer

Research reported that being overweight or obese can increase the risk of

CRC, whereas increased physical activity is associated with reduction in

risk.6

Non-modifiable risk factors include ageing, male

gender, positive family history, history of familial adenomatous

polyposis, Lynch syndrome (previously known as hereditary non-polyposis

CRC), colonic polyp, and ulcerative colitis.

Based on local epidemiology, CRC is more common in

men and its risk increases significantly from age 50 years.1 Regarding family history, according to a local study,

80% to 90% of CRC cases are sporadic, and the remaining 10% to 20% are

familial cancers.7 The cancer risk

of individuals with a positive family history may vary according to the

age of diagnosis of CRC in the index patient and the number of affected

first-degree relatives. The younger the age of diagnosis of CRC in the

index patient, the higher the risk of CRC of family members would be. In a

meta-analysis, the estimated relative risk of individuals with relatives

diagnosed with CRC at age <50 years was 3.55, whereas that for

relatives diagnosed with CRC at age ≥50 years was 2.18.8

Familial adenomatous polyposis is an autosomal

dominant disorder caused by germline mutation of the adenomatous polyposis

coli gene located on the short arm of chromosome 5 (5q21-22).9 Individuals with this mutation have a 95% chance of

developing CRC by age 50 years.10

Lynch syndrome is another dominantly inherited CRC syndrome. It is caused

by germline mutation in one of the genes responsible for the repair of

mismatches during DNA replication. The lifetime risk of CRC for those

carrying this mutation is estimated to be 50% to 80%.10

Ulcerative colitis has been associated with an

increased risk of developing CRC, likely caused by long-standing chronic

inflammation.11 Moreover, CRC

arises predominantly from adenomatous polyps, which can develop into CRC

after ≥10 years.12 Development of

larger polyps, villous histology, and severe dysplasia are important

indicators for progression into CRC.13

Primary prevention

Primary prevention is of utmost importance for the

prevention of CRC as many of the risk factors are modifiable. For

preventing CRC, the CEWG recommends:

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention involves screening individuals

without symptoms in order to detect disease or identify individuals who

are at increased risk of disease. Since CRC arises predominantly from

precancerous adenomatous polyps developed over a long latent period, it is

one of the few cancers that can be effectively prevented through organised

and evidence-based screening. In general, for CRC screening, individuals

can be classified into “average risk” and “increased risk” groups.

According to screening recommendations made by the

CEWG, increased-risk individuals are those with a significant family

history, such as an immediate relative diagnosed with CRC at age ≤60

years; more than one immediate relatives diagnosed with CRC irrespective

of age at diagnosis; or immediate relatives diagnosed with hereditary

bowel diseases. Average-risk individuals are those aged 50 to 75 years who

do not have the aforesaid family history.

Screening for general population at average risk

Since 2010, the CEWG has recommended that

average-risk individuals aged 50 to 75 years should consult their doctors

to consider one of the following screening methods:

The CEWG made the above recommendations after

taking into consideration local epidemiology, research evidence, as well

as international guidelines and practices.

The age range recommended for CRC screening in the

general population should be defined to capture the largest number of CRC

cases while taking into account the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of

screening tests, local epidemiology, and anticipated benefits and harms to

the screened population. In Hong Kong, the risk of CRC increases

significantly from age 50 years.1

Guidelines in US14 15 and Singapore16

recommend starting screening at age 50 years, whereas guidelines in the UK

recommend starting screening at age >50 years.17

Regarding screening modalities, FOBT, sigmoidoscopy

and colonoscopy have been shown to reduce mortality from CRC. Faecal

occult blood tests can decrease CRC mortality by 15% to 33%, according to

findings from large-scale randomised control trials.18 19 20 A Cochrane review showed that screening by FOBT might

reduce CRC mortality in the average risk population by 16%.21 Sigmoidoscopy has been shown to lead to a 28% risk

reduction in overall CRC mortality and a 43% risk reduction in distal CRC

mortality in a meta-analysis.22

Colonoscopy was associated with 61% reduction in CRC mortality in another

meta-analysis.23

International guidelines and practices for CRC

screening in the general population mainly recommend annual or biennial

FOBT, sigmoidoscopy once every 5 years, or colonoscopy once every 10

years.15 16

To reduce the burden arising from CRC, the

government launched the 3-year Colorectal Cancer Screening Pilot Programme

(Pilot Programme) on 28 September 2016 to provide subsidised screening by

phases to average risk Hong Kong residents born in 1946 to 1955 (aged

61-70 years in 2016). The screening workflow comprises two stages.

Participants first receive a subsidised faecal immunochemical test (a new

version of FOBT) from an enrolled primary care doctor. If the faecal

immunochemical test result is positive, the participant receives a

subsidised colonoscopy examination from a colonoscopy specialist enrolled

in the Pilot Programme. In August 2018, the government regularised the

programme and would progressively extend it to cover individuals aged 50

to 75 years. Details are available at http://www.colonscreen.gov.hk.

Screening for increased-risk individuals

In 2017, the CEWG updated the CRC screening

recommendations for increased-risk individuals. The key change was related

to the interval for colonoscopy screening among individuals with

significant family history of CRC but without genetic mutations.

For patients with CRC with identifiable genetic

mutations, including Lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis,

the CEWG recommends two-tier screening for their family members. Genetic

testing should be conducted first, followed by endoscopic examination at

specified and shorter intervals if the genetic test is positive. This

reduces the number of unnecessary investigations among those with strong

family history but without proven genetic mutation, decreasing the risk of

potential complications arising from repeated endoscopic procedures.

These recommendations were made after considering

the scientific evidence and international guidelines and practices.

Individuals who are carriers of genetic mutations

associated with familial adenomatous polyposis or Lynch syndrome and

individuals with a family history of CRC are at increased risk of CRC.

Colorectal cancer in these individuals tends to be diagnosed at a younger

age and progresses more aggressively than CRC in the general population.24 25

International recommendations emphasise that CRC

screening in increased-risk individuals needs to start earlier in their

lifetime and be repeated at shorter intervals. Recommendations made by

countries and by professional organisations on screening for

increased-risk individuals generally suggest the use of colonoscopy and

sigmoidoscopy as the screening methods.15

16 26

27 28

29 30

31 32

The recommended endoscopic screening method for

carriers of genetic mutations associated with Lynch syndrome is annual or

biennial colonoscopy. It is recommended to start screening at age 20 to 25

years in the US15 26 27 and

Singapore,16 at age 25 years in

UK,28 and at age 25 years or 5

years earlier than the age at diagnosis of the youngest affected member of

the family (whichever is the earliest) in Australia.29 The guidelines issued by the World Gastroenterology

Organization (WGO) recommend that screening should start at age 20 to 25

years or 10 years earlier than the youngest age at CRC diagnosis in the

family, whichever comes first.30

The recommended endoscopic screening method for

carriers of genetic mutations associated with familial adenomatous

polyposis is mainly annual or biennial flexible sigmoidoscopy, or annual

colonoscopy. It is recommended to start screening at age 10 to 12 years in

the US15 and Singapore,16 at age 13 to 15 years in the UK,28 and at age 12 to 15 years (later age is recommended)

in Australia.29 The guidelines

issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network suggest screening

should start at age 10 to 15 years,31

32 whereas the WGO recommendation

is to start screening at age 10 to 12 years.30

International guidelines recommend endoscopic

screening for individuals who have one first-degree relative diagnosed

with CRC at age 50 to 60 years.15

16 26

28 29

30 31

32 33

Individuals with more than one first-degree relative with CRC irrespective

of age at diagnosis are considered at increased risk and endoscopic

screening at more frequent intervals is recommended.15 16 26 28 29 30 31 32 For these

individuals, the recommended endoscopic screening method is to receive

colonoscopy every 5 years.15 16 26 29 30 31 32 It is

recommended to start screening at age 40 to 50 years, or 10 years prior to

the age at diagnosis of the youngest affected relative.15 16 26 29 30 31 32

Currently, patients with CRC may be referred for

genetic counselling and testing. These services are provided at centres

run by non-governmental organisation, including the Hereditary

Gastrointestinal Cancer Genetic Diagnosis Laboratory

(http://www.patho.hku.hk/colonreg.htm); the Department of Health’s

Clinical Genetic Service (http://www.dh.gov.hk); and the private sector.

Although referral criteria for testing may differ among these testing

services, commonly adopted criteria include strong family history,

occurrence of multiple cancers in a single individual, early onset of

disease, presence of pathogenic mutation in the cancer predisposition

gene, and clinically suspected hereditary cancer syndrome.

Emerging evidence for colorectal cancer screening

In the past 2 years, new evidence supporting the

effectiveness of CRC screening has emerged which reinforces the CEWG

recommendations.

A systematic review reported that sigmoidoscopy is

associated with a 27% reduction in CRC-specific mortality in four

randomised controlled trials and that biennial FOBT screening reduced

CRC-specific mortality by 9% to 22% at 19.5 to 30 years of follow-up in

five randomised controlled trials compared with no screening in the

average-risk population.34 35

Separately, a prospective study in Sweden found

that colonoscopic surveillance for increased-risk individuals with

significant family history is a cost-effective intervention to prevent

CRC.36

In addition, the US Preventive Services Task Force,37 the US Multi-Society Task Force

on Colorectal Cancer Screening,38

and the American Cancer Society39

40 updated their recommendations

for CRC screening in 2016 and 2017. All continue to recommend annual FOBT,

sigmoidoscopy every 5 to 10 years, or colonoscopy every 10 years as

appropriate screening modalities for average-risk individuals.

Conclusion

After considering local epidemiology, scientific

evidence, and local and international screening guidelines and practices,

the CEWG reaffirms in 2017 the CRC screening recommendations for

average-risk individuals and updates the screening interval relating to

the recommendations for increased-risk individuals with significant family

history of CRC, as summarised in the Table. A leaflet and booklet on the CEWG

recommendations are available

(http://www.chp.gov.hk/en/content/9/25/31932.html) for downloading and

dissemination to the general public to help them make informed choices.

The CEWG will continue to monitor emerging local and international

evidence and practice to ensure evidence-based CRC prevention and

screening recommendations are up to date.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to

the concept or design; acquisition of data; analysis or interpretation of

data; drafting of the article; and critical revision for important

intellectual content.

Declaration

As editors of this journal, DVK Chao, HHF Loong,

and MCS Wong were not involved in the peer review process of this article.

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. All authors had

full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final

version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity. An earlier version of this article was published online on the

Centre for Health Protection website

(https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/cewg_crc_professional_hp.pdf).

References

1. Hong Kong Cancer Registry. Colorectal

cancer in 2015. 2016. Available from:

http://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/pdf/factsheet/2015/colorectum_2015.pdf.

Accessed 31 Oct 2017.

2. Department of Health and Census and

Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR Government. Mortality Statistics;

2016.

3. World Health Organization. Q&A on

the carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat.

2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/features/qa/cancerred-meat/en/.

Accessed 6 Sep 2017.

4. Bradbury KE, Appleby PN, Key TJ. Fruit,

vegetable, and fiber intake in relation to cancer risk: findings from the

European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Am J

Clin Nutr 2014;100(Suppl l):394S-398S. Crossref

5. International Agency for Research on

Cancer, World Health Organization. List of classifications by cancer sites

with sufficient or limited evidence in humans, Vol 1 to 121. 2018.

Available from: https://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Classification/Table4.pdf.

Accessed 6 Sep 2017.

6. World Cancer Research Fund and American

Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and

Colorectal Cancer. World Cancer Research Fund International; 2017.

7. Ho JW, Yuen ST, Lam TH. A case-control

study on environmental and familial risk factors for colorectal cancer in

Hong Kong: chronic illnesses, medication and family history. Hong Kong Med

J 2006;12(Suppl 1):S14-6.

8. Butterworth AS, Higgins JP, Pharoah P.

Relative and absolute risk of colorectal cancer for individuals with a

family history: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:216-27. Crossref

9. Half E, Bercovich D, Rozen P. Familial

adenomatous polyposis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2009;4:22. Crossref

10. Samadder NJ, Jasperson K, Burt RW.

Hereditary and common familial colorectal cancer: evidence for colorectal

screening. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:734-47. Crossref

11. Castaño-Milla C, Chaparro M, Gisbert

JP. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the declining risk of colorectal

cancer in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:645-59. Crossref

12. Winawer SJ. Natural history of

colorectal cancer. Am J Med 1999;106:3S-6S. Crossref

13. Terry MB, Neugut AI, Bostick RM, et

al. Risk factors for advanced colorectal adenomas: a pooled analysis.

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002;11:622-9.

14. Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality, Department of Health & Human Services, US Government. US

Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: Summary

of Recommendations. October 2008. Available from:

http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspscolo.htm. Accessed 8 Oct 2008.

15. Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et

al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal

cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American

Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and

the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin 2008;58:130-60. Crossref

16. Ministry of Health, Singapore

Government. Cancer Screening: MOH Clinical Practice Guidelines 1/2010,

February 2010.

17. The UK NSC recommendation on bowel

cancer screening. Available from:

https://legacyscreening.phe.org.uk/bowelcancer. Accessed 10 Sep 2018.

18. Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO,

Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood

screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet 1996;348:1472-7. Crossref

19. Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J,

Jørgensen OD, Søndergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal

cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet 1996;348:1467-71. Crossref

20. Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, et al.

Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult

blood. Minnesota colon cancer control study. N Engl J Med

1993;328:1365-71. Crossref

21. Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Irwig L,

Towler B, Watson E. Screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal

occult blood test, Hemoccult. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2007;(1):CD001216.

22. Shroff J, Thosani N, Bartra S, Singh

H, Guha S. Reduced incidence and mortality from colorectal cancer with

flexible-sigmoidoscopy screening: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol

2014;20:18466-76. Crossref

23. Pan J, Xin L, Ma YF, Hu LH, Li ZS.

Colonoscopy reduces colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in patients

with non-malignant findings: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol

2016;111:355-65. Crossref

24. Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, et

al. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale.

Gastroenterology 1997;112:594-642. Crossref

25. Rose P, Dunlop M, Burton H, Haites N.

Screening for late onset genetic disorders colorectal cancer. The UK

National Screening Committee; October 2000.

26. Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, et

al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer

screening 2009 [corrected]. American J Gastroenterol 2009;104:739-50. Crossref

27. Giardiello FM, Allen JI, Axilbund JE,

et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome:

a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal

Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1159-79. Crossref

28. Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ,

et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in

moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). Gut 2010;59:666-89. Crossref

29. National Health and Medical Research

Council, Australia Government. Clinical Practice Guidelines: The

Prevention, Early Detection and Management of Colorectal Cancer; December

2005.

30. Winawer S, Classen M, Lambert R, et

al. World Gastroenterology Organisation/International Digestive Cancer

Alliance Practice Guidelines: Colorectal Cancer Screening. South African

Gastroenterology Review 2008;6.

31. National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Rectal Cancer Version 2;

2016.

32. National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon Cancer Version 1;

2017.

33. Sung JJ, Ng SC, Chan FK, et al. An

updated Asia Pacific consensus recommendations on colorectal cancer

screening. Gut 2015;64:121-32. Crossref

34. Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al.

Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic

review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA 2016;315:2576-94. Crossref

35. Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al.

Screening for colorectal cancer: a systematic review for the US preventive

services task force. Evidence synthesis No. 135. Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality; 2016.

36. Sjöström O, Lindholm L, Melin B.

Colonoscopic surveillance—a cost-effective method to prevent hereditary

and familial colorectal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol 2017;52:1002-7. Crossref

37. US Preventive Services Task Force,

Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US

preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA

2016;315:2564-75. Crossref

38. Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al.

Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients

from the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer.

Gastroenterology 2017;153:307-23. Crossref

39. American Cancer Society. American

Cancer Society recommendations for colorectal cancer early detection. July

2017. Available from:

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acsrecommendations.html.

Accessed 6 Sep 2017.

40. Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, et al.

Cancer screening in the United States, 2017: a review of current American

Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA

Cancer J Clin 2017;67:100-21. Crossref