© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF

MEDICAL SCIENCES

Handbook of Pathology

US Khoo, FRCPath, FHKAM (Pathology)

Guest Contributor, Education & Research

Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

The Handbook of Pathology (Fig

1) was written by Professor Wang Chung-yik (1888-1930) during his

tenure as the first and Foundation Chair of Pathology at The University of

Hong Kong, a position he held from 1919 to his death. Wang was the first

ethnic Chinese to hold a full-time chair at the University.1 Published in 1925 as a textbook for students with 282

illustrations, the Handbook is unique not only as the first

Pathology textbook to be written by a Hong Kong author, but also for its

unusual approach.

Figure 1. A copy of the Handbook of Pathology (1925) written by Wang Chung-yik and kindly donated to the museum by his son, Dr Ian Wang (courtesy of the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society)

As Wang explained in his preface, the book was

“written with the object of presenting in a short, concise form the more

important and salient points in Pathology, such as appear to the author to

meet the main requirements of the students of medicine for whom this is

primarily intended.”2 Thus, the Handbook

covers only the more common disease conditions of that time, with special

prominence given to morbid anatomy, which the author considered essential

to the understanding and interpretation of functional disorders in

disease. Each entity covered is well illustrated, as far as possible, with

a photograph of a well-preserved gross specimen and/or a photomicrograph

or diagrammatic representation of the condition. These illustrations were

undoubtedly derived from a teaching collection of museum specimens and

microscopic sections which Wang had painstakingly built up with the

establishment of the pathology department at The University of Hong Kong.

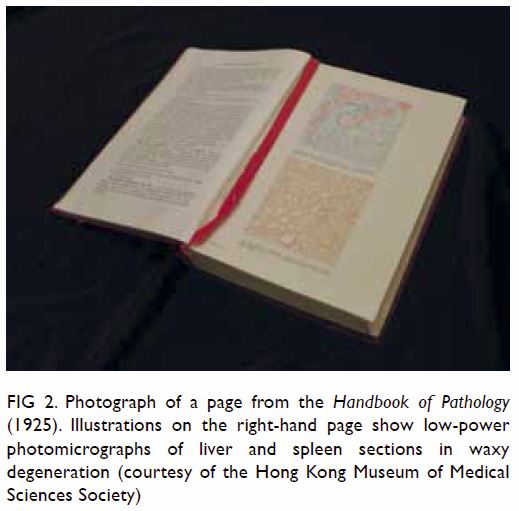

Interestingly, throughout the chapters, microscopic

appearance is presented before nakedeye appearance. The diagrammatic

representations presented are actually low-power photomicrographs, mostly

taken at ×46 magnification, with relevant important structures coloured or

highlighted to facilitate easier appreciation of the condition (Fig

2).

Figure 2. Photograph of a page from the Handbook of Pathology (1925). Illustrations on the right-hand page show low-power photomicrographs of liver and spleen sections in waxy degeneration (courtesy of the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society)

Unlike conventional textbooks, which are usually

arranged according to organ systems, or by the commonly described

pathological processes, the Handbook is divided into chapters

based on aetiological lines or characteristic tissue changes, with lesions

of a similar or related nature grouped together for discussion (Fig

3). Wang believed that this aetiological approach emphasising the

causes of tissue or cell change in accordance with his own concepts would

be most helpful for his students.

Figure 3. Wang Chung-yik in his MD graduation robes, 1916 (courtesy of the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society)

The early chapters of the Handbook deal

with the following introductory topics in turn: morphology of cells;

reproduction of cells; degeneration and allied changes in cells; oedema;

hyperaemia; thrombosis and embolism; infarction; atrophy; hypertrophy and

hyperplasia; and metaplasia. In each of these chapters, the changes

affecting different organs are detailed in turn. The chapters that follow

deal with functional abnormalities: dilatation; haemorrhage; pigmentation;

fever; shock; and inflammation. These chapters also encompass multiple

organs for each abnormality. In particular, the chapter on inflammation is

of significant length, totalling over 100 pages, dealing with inflammation

in one organ system at a time. The remaining chapters cover: acute

infective diseases; diseases due to known bacteria or parasitesa–a long

chapter with significant coverage of syphilis and tuberculosis; disease

due to filter passers; disorders of internal secretion; diseases due to

metabolic disturbances; diseases affecting the blood and blood-forming

organs, and related conditions; and finally tumours–another chapter that

takes up more than one fifth of the book.

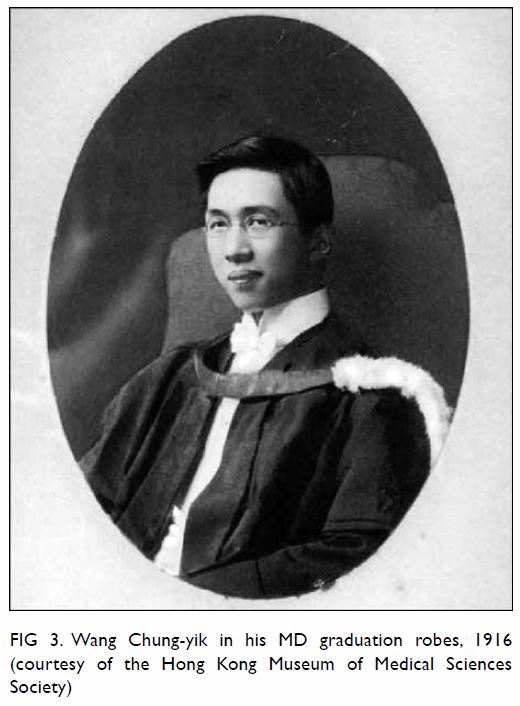

Wang’s appointment in 1919 with his subsequent

return to Hong Kong in 1920, marks the start of the department of

pathology which he built from scratch, in a new building on the main

university campus. Wang was a graduate of the Hong Kong College of

Medicine, which was the only tertiary-level educational institute in Hong

Kong at that time.3 The Licentiate

awarded by the College to graduates at that time was not recognised by the

General Medical Council of the United Kingdom; therefore, Wang enrolled at

the University of Edinburgh, obtaining his MB ChB degree in 1910, after

only 2 years of study.1 Motivated

by a desire to learn more about scientific and technological advances in

the major centres of medical education in the West, Wang then undertook a

period of intensive training, obtaining the Edinburgh Diploma of Tropical

Health and Hygiene in 1911, the Diploma of Public Health at Manchester in

1912, and the BSc in Bacteriology and Comparative Pathology in 1913, also

in Manchester.1 He then worked in

the laboratory of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh as an

independent researcher from 1913 to 1919.4

His particular interest was in the field of tuberculosis, which was the

basis of his MD thesis “A study in some phases of tuberculosis, with

special reference to the incidence of bovine infection and the question of

latency and prevalence of the disease,” for which he was awarded a gold

medal from the University of Edinburgh in 19161

(Fig 3). Indeed, tuberculosis research was his

life-long interest.

When the superintendent of the Royal College of

Physicians of Edinburgh laboratory was called up for military service

during the First World War, Wang was appointed Interim Assistant

Superintendent, assuming the responsibility for the general running of the

laboratory and the reporting of many type of specimens submitted for

clinical diagnosis. This included handling specimens from the influenza

pandemic of 1918 and diagnostic work in venereal diseases.

As well as head of the Pathology Department at the

University of Hong Kong, Wang was an Honorary Consultant in Pathology to

the Hong Kong Government and also acting Government Bacteriologist from

1921 to 1922. During this period, Wang was also in charge of the

Government Bacteriological Institute (the building which now houses the

Museum) and the Government Mortuary which served the whole of Hong Kong

Island. Wang also had the responsibility to report on specimens from

university clinics and wards in the Government Civil Hospital, conduct

post-mortem examinations, supervise the production of cowpox, typhoid,

rabies, and autogenous vaccines, and survey various infectious diseases.5

Despite these heavy clinical duties, Wang dedicated

himself to his teaching responsibilities in equally serious fashion.

Tragically, Wang contracted tuberculosis at the height of his career.6 When he could no longer speak on account of

tuberculosis affecting his larynx, he wrote down his lectures and asked an

assistant to read it out of him.6

With little time left for research, his interest in tuberculosis and

laboratory medicine nevertheless continued, with publication of a series

of papers in the Lancet on different aspects of laboratory testing.7 8 9 He passed away at the young age of 42.6 He was remembered as a kind and conscientious teacher

interested in the welfare of his students (personal communication, Dr

Chiu-kwong Yu; 1998). As summed up in his obituary, “There is no doubt

that had his life been spared he would have made his department in the

Hong Kong University a distinguished centre of teaching and research”.10

A copy of the Handbook of Pathology that

was kindly donated by the author’s son, Dr Ian Wang, is on display in the

Old Laboratory at the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences, in the

permanent exhibit entitled ‘Three Notable Pathologists’. The Foundation

stone of the School of Pathology and the School of Tropical Medicine,

dated 1918, served as another reminder of his legacy. The stone was a

prominent landmark at the entrance of the University Pathology Building in

Queen Mary Hospital until the building was decommissioned in 2018.

References

1. Ho FC. Hong Kong’s first Professor of

Pathology and the laboratory of the Royal College of Physicians of

Edinburgh. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2011;41:67-72. Crossref

2. Wang CY. Handbook of Pathology. London:

John Bale, Sons & Danielsson; 1925.

3. Fu L. From surgeon-apothecary to

statesman: Sun Yat-sen at the Hong Kong College of Medicine. J R Coll

Physicians Edinb 2009;39:166-72.

4. RCPE Archives. Monthly reports of

Superintendent, RCPE Laboratory, 1913-28.

5. Ho FC. The silent protector, a short

centennial history of Hong Kong’s Bacteriological Institute. Hong Kong:

Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society; 2006: 32-56.

6. Anon. Obituary: Chung Yik Wang. Caduceus

1931;10:1-2.

7. Wang CY. A precipitation test for

syphilis. Lancet 1922;199:274-6. Crossref

8. Wang CY, Basto RA. Further study of a

precipitation test for syphilis. Lancet 1923;201:1262-3. Crossref

9. Wang CY. A new culture medium. Lancet

1928;212:466-7. Crossref

10. Anon. Obituary: Chung Yik Wang

1888-1930. J Pathol Bacteriol 1931;34:189.