Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Aug;24(4):378–83 | Epub 27 Jul 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj187217

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Telepsychiatry for stable Chinese psychiatric

out-patients in custody in Hong Kong: a case-control pilot study

KM Cheng, MB, BS, FHKAM (Psychiatry)1;

Bonnie WM Siu, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Psychiatry)2; Cherie CY Au

Yeung, BSc, MStat2; TP Chiang, MB, BS, FHKAM (Psychiatry)1;

MH So, BSc3; Mick CW Yeung, FHKAN, BSc3

1 Department of General Adult

Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

2 Department of Forensic Psychiatry,

Castle Peak Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

3 Correctional Services Department,

Wanchai, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Bonnie WM Siu (swm810@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: In Hong

Kong, persons in custody receive primary medical care within the

institutions of the Correctional Services Department (CSD). However, for

psychiatric care, persons in custody must attend specialist out-patient

clinics (SOPCs), which may cause embarrassment and stigmatisation. The

aim of this interventional pilot study was to compare teleconsultations

with face-to-face consultations for a group of stable Chinese

psychiatric out-patients in custody.

Methods: A total of 86 stable

Chinese male out-patients in custody were recruited for psychiatric

teleconsultations. They were compared with 249 age-matched Chinese male

out-patients in custody attending standard face-to-face psychiatric

consultations at other SOPCs. The two groups had comparable baseline

characteristics including age, education level, and 12-item Chinese

General Health Questionnaire (C-GHQ-12) score. A satisfaction survey of

patients towards the teleconsultation was also carried out.

Results: Compared with the

face-to-face consultation group, the teleconsultation group showed a

significantly better result in the difference in C-GHQ-12 scores before

and after consultations (P=0.023). The correlation between the first and

second teleconsultations also showed a moderate positive relationship (r=0.309).

The satisfaction survey showed a favourable response to

teleconsultations. No significant adverse events were identified for the

teleconsultation group.

Conclusions: The results suggest

that teleconsultations are a sustainable and safe alternative to

face-to-face consultations for stable Chinese psychiatric out-patients

in custody.

New knowledge added by this study

- Psychiatric teleconsultations are a sustainable and safe alternative to face-to-face consultations for stable Chinese psychiatric out-patients in custody.

- The intrinsic problems of embarrassment and stigmatisation caused to persons in custody, their risk of abscondence, and the issue of general public safety can all be addressed with this promising alternative mode of psychiatric care for stable Chinese psychiatric out-patients in custody.

Introduction

Telepsychiatry is the practice of delivering mental

health consultations at a distance. New developments in information and

communication technologies have allowed telepsychiatry to become a viable

method of providing services to patients in rural or remote locations with

limited access to medical services.1

2 3

Telepsychiatry has been used in prison settings for more than 20 years.4 A demonstration of telepsychiatry

in prison in the US in 1996 concluded that this practice was

cost-effective.5 Prison

administrators even claimed that there were fewer assault incidents after

its use.5 In Hong Kong, the use of

telepsychiatry can be dated back to 1998.6

Currently, persons in custody (PICs) in Hong Kong

receive primary medical care within the institutions of the Correctional

Services Department (CSD). However, for specialist psychiatric service for

their mental problems, PICs must attend psychiatric specialist out-patient

clinics (SOPCs) of the Hospital Authority. In addition, most psychiatric

drugs are available only in SOPCs.

For security reasons, PICs must be escorted by at

least two CSD staff and be handcuffed on every occasion they need to

attend follow-up at a SOPC. Such an exposing arrangement inevitably causes

much embarrassment and stigmatisation for PICs. There is also a potential

risk to the public in the event of abscondence from custody. The PIC may

also experience travel sickness during the journey between the

correctional facilities and the SOPC; most correctional facilities in Hong

Kong are situated in relatively remote areas, so the journey times can be

long. Furthermore, other patients in the SOPC may feel uncomfortable

witnessing a PIC being handcuffed. Some SOPCs manage this problem by

placing the PIC in a special corner or room, depending on availability.

Face-to-face consultation is the gold standard for

medical practice. However, telepsychiatry is suitable for PICs and might

confer additional benefits for this group of patients. Direct physical

examinations are typically unnecessary for stable psychiatric patients

during follow-up. Additionally, the nurse at the CSD site can help measure

vital signs such as blood pressure, pulse, and temperature. Therefore,

offering PICs psychiatric teleconsultations cannot only maintain their

usual psychiatric care but also reduce embarrassment, stigmatisation, and

the risk of abscondence. Furthermore, it can also reduce the need for

special arrangements in SOPCs.

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no

previous studies exploring the effect of psychiatric teleconsultations for

Chinese psychiatric out-patients under the legal custody of the CSD in

Hong Kong. The main aim of the present study was to explore the use of

psychiatric teleconsultations for stable Chinese psychiatric out-patients

under the legal custody of the CSD in Hong Kong. The desired outcome was

to maintain the clinical interests of PICs and to provide them with

appropriate psychiatric services using telecommunications in a safe,

humane, and cost-effective manner. This was an interventional pilot study

evaluating the effect of psychiatric teleconsultations on the general

health of an intervention group of clinically stable Chinese male

psychiatric out-patients who were under the custody of the CSD as compared

with a matched control group of Chinese male psychiatric out-patients

under the usual type of care (ie, face-to-face consultation with a

psychiatrist at a SOPC). In addition, the satisfaction of patients towards

psychiatric teleconsultations was assessed.

The null hypotheses of this study were as follows:

1. After the consultation, the psychological health of the intervention group is worse than that of the control group;

2. The effect of psychiatric teleconsultations is unsustainable;

3. Patients in the intervention group are unsatisfied with the psychiatric teleconsultations;

4. Adverse events occur during psychiatric teleconsultations.

1. After the consultation, the psychological health of the intervention group is worse than that of the control group;

2. The effect of psychiatric teleconsultations is unsustainable;

3. Patients in the intervention group are unsatisfied with the psychiatric teleconsultations;

4. Adverse events occur during psychiatric teleconsultations.

Methods

This was an interventional pilot study conducted by

the Hospital Authority in collaboration with the Hong Kong CSD.

Participants

The study period was from June 2014 to May 2016.

Participants were aged 21 to 64 years. The intervention group comprised

Chinese patients in custody attending follow-up at the SOPC of Castle Peak

Hospital (CPH), Hong Kong. The control group included Chinese patients in

custody attending follow-up at other SOPCs in Hong Kong. In this study,

only male PICs were included because of logistic and feasibility reasons.

Exclusion criteria applied when selecting intervention and control

participants for this study included: (a) patients with mental instability

or with prominent and recent change/deterioration in mental condition,

such as those who were suicidal or homicidal, or who had delirium or acute

psychosis; (b) patients who required regular blood tests, such as those

taking clozapine; (c) patients requiring other tests/investigations only

available in SOPC or Hospital Authority hospitals; (d) patients requiring

drug administration in SOPC, such as depot antipsychotics; (e) patients

attending SOPC for the first time; or (f) patients with visual or auditory

deficits that might impair the ability to interact via video-conferencing. Eligible patients meeting the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. Written informed consent was

obtained from the intervention and control participants.

Sample size

A sample size of at least 80 participants for the

intervention group with an intervention-to-control ratio of approximately

1:3 was adopted in this study. This was an affordable and representative

sample size with reference to the number of stable psychiatric

out-patients in custody attending follow-up appointment at the SOPC of CPH

during the study period.

Assessment tools

Socio-demographic and clinical data including age,

education level, and principal psychiatric diagnosis according to the 10th

revision of the International Classification of Diseases were obtained.7 The intervention and control participants were

requested to complete the Chinese version of the 12-item General Health

Questionnaire (C-GHQ-12).8 The GHQ

is a self-administered test used for evaluating the psychological

components of ill health and is helpful in screening for general emotional

distress.9 10 The GHQ possesses adequate content validity and

construct validity, and good internal consistency has been demonstrated

with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.82 to 0.93.9

10 The Chinese and English

versions of the GHQ have been adopted for Chinese and non-Chinese

subjects, respectively.8 9 10 The

C-GHQ-12 consists of 12 items, with each item assessing the severity of a

mental problem using a 4-point Likert scale.8

The six positive items were rated from 1 (more than usual) to 4 (much less

than usual) and the six negative items from 1 (never) to 4 (much more than

usual); thus, a higher score indicates a more severe mental health

condition. In this study, the pre-consultation and post-consultation

C-GHQ-12 scores for each patient were obtained. The difference between the

two scores (ie, the pre-post difference) was used as a proxy measurement

of the quality of consultation.

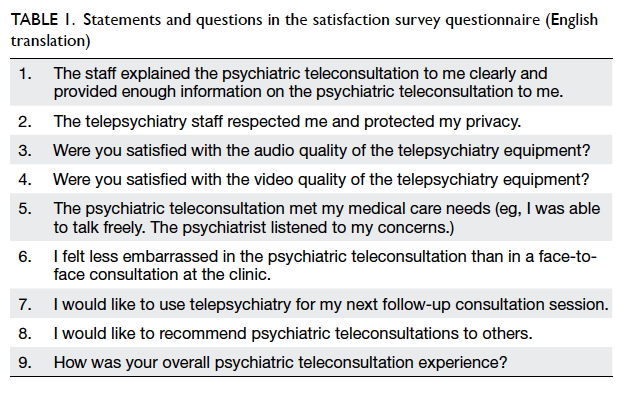

The intervention participants were also requested

to complete a questionnaire in Chinese designed to measure the patient

satisfaction regarding the psychiatric teleconsultation. The questionnaire

consisted of nine statements/questions rated according to a 5-point Likert

scale, from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) or from 1 (very

satisfied) to 5 (very dissatisfied). The questionnaire was designed by the

authors as there were no available validated Chinese questionnaires

suitable for assessing patient satisfaction of telepsychiatry at the time

of the study (English translations of the statements/questions in the

questionnaire are listed in Table 1).

Procedure

The intervention participants were transferred from

various CSD institutions to the Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre, Hong Kong,

for the psychiatric teleconsultation. On the scheduled day of

consultation, the CSD staff brought two portable video-conferencing

devices to CPH. Registration was performed only after the device had been

checked as functional. All persons in the consultation rooms at the CSD

site and at the CPH site were identified to each other prior to the

consultation session. Consultation rooms provided at both sites were

appropriately set up with particular attention to audio and visual

privacy, lighting, backdrop, and gaze angle. A qualified CSD nurse was

present in the consultation room at the CSD site together with the

patient. There was also a CSD medical doctor at the reception centre

during the psychiatric teleconsultation, in case emergency medical

treatment was needed. After the consultation, the CSD staff collected the

medicine for the patient according to the usual procedures. For the

intervention participants, the maximum number of consecutive psychiatric

teleconsultations was set as four, after which a face-to-face follow-up

consultation must follow. The control participants attended only

face-to-face consultations at other SOPCs. Both groups of participants filled in the C-GHQ-12

within 7 days before the consultation and again within 7 days after the

consultation. In addition, the intervention participants filled in the

satisfaction survey questionnaire after the psychiatric teleconsultation.

Any major adverse events, such as medical or psychiatric emergencies, were

recorded.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the

baseline profile of the participants’ socio-demographic and clinical

characteristics as well as pre- and post-consultation C-GHQ-12 scores and

satisfaction survey questionnaire responses. Chi squared test and

two-samples t test were performed to assess if there were

differences in the baseline characteristics between the intervention and

control participants. A non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was

performed to test if there were differences in the pre-post difference in

C-GHQ-12 score between intervention and control participants attending

their first consultation. Spearman’s correlation was used to compute the

correlation between the pre-post difference in C-GHQ-12 score of the first

and second teleconsultations among the intervention participants. All

statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows, version 12.0

(SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US), with P<0.05 considered as statistically

significant in this study.

Results

During the study period, there were 377 PIC

scheduled attendances at CPH. Of these, 221 PIC scheduled attendances were

suitable for psychiatric teleconsultation; however, for 49 of the suitable

PIC scheduled attendances, the PICs refused to give consent for this

study. Finally, 172 PIC psychiatric teleconsultation attendances were

included. Each participant could have more than one psychiatric

teleconsultation attendance during the study period. Therefore, 86

participants aged 21 to 64 years who were stable Chinese male psychiatric

out-patients and who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria for

psychiatric teleconsultations in CPH were included. For the control group,

249 male patients within the same age range (21-64 years) were recruited.

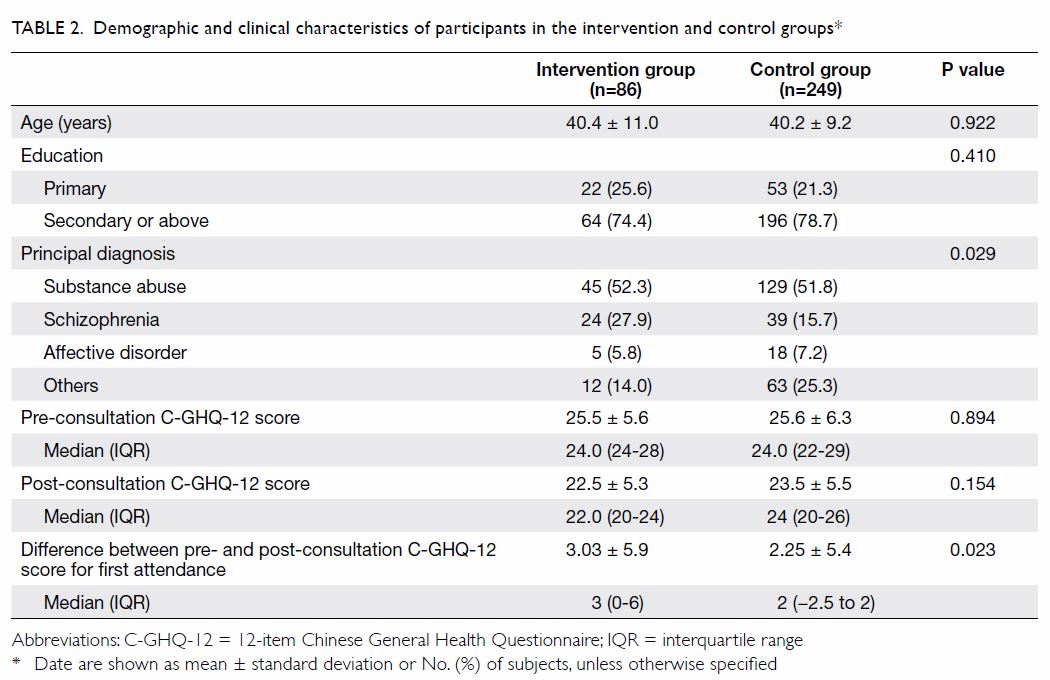

Table 2 compares patient characteristics between the

intervention and control groups. There were no significant differences in

the age and education profile between the two groups. The mean age of both

groups was approximately 40 years. Approximately three quarters of the

participants in each group had attained education at the secondary level

or above. There was a significant difference in the principal psychiatric

diagnosis (P=0.029). Slightly over 50% of each group were diagnosed as

substance abuse. A larger proportion of intervention participants had

schizophrenia (28%) than did the control participants (16%). There were no

significant differences in the mean pre-consultation C-GHQ-12 score

between the two groups.

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in the intervention and control groups*

The mean (standard deviation) on-air time duration

of the psychiatric teleconsultations was 6.33 (3.58) minutes. There were

no significant adverse events associated with teleconsultations reported

during the study. The pre-post difference in C-GHQ-12 score of the

intervention participants was significantly higher than that of the

control participants (P=0.023; Table 2). Furthermore, among 29 intervention

participants who had at least two teleconsultations, the association

between pre-post difference in C-GHQ-12 score of the first and second

teleconsultations was moderately strong (r=0.309, P=0.103) but did

not reach the level of significance set for this study. The possible scores on the satisfaction survey

questionnaire ranged from 9 (the most satisfied) to 45 (the least

satisfied). The mean (standard deviation) satisfaction score of the

intervention group was 16.48 (4.35). No major adverse events were reported

throughout the study.

Discussion

Telepsychiatry is not a new development in Hong

Kong. Since 2001, the use of telepsychiatry has been shown to increase

access to care.11 Studies have

shown that telepsychiatry is an effective means to provide psychogeriatric

services to residents of care homes,11

and cognitive intervention for community-dwelling elderly patients with

memory problems.12 This was the first intervention pilot study in Hong Kong exploring the effect of psychiatric teleconsultation for Chinese

psychiatric out-patients under the legal custody of the CSD. Our study

compared the effectiveness of psychiatric teleconsultations with that of

face-to-face consultations among PIC receiving out-patient psychiatric

treatment. The two groups of stable Chinese male out-patient participants

had the same baseline characteristics in age, education level, and

pre-consultation C-GHQ-12 score. The results showed that the standard of

care of teleconsultations was comparable to that of face-to-face

consultations. The pre-post difference in C-GHQ-12 score for

teleconsultations had a marginally larger positive increase than did

face-to-face consultations. The intervention participants also showed high

satisfaction with the psychiatric teleconsultation service, with a mean

satisfaction score above the 80th percentile. This results is similar to

that of a previous study in the US that compared the effectiveness of

telepsychiatry and in-person psychiatry sessions among 71 parolees over a

6-month follow-up period, revealing high satisfaction with telepsychiatry

treatment.13 In the present study,

the pre-post difference between C-GHQ-12 score of the first and second

psychiatric teleconsultations showed a moderate positive relationship,

suggesting a consistent and sustainable clinical effect of telepsychiatry

between sessions. Importantly, there were no reports of significant

adverse events. Therefore, telepsychiatry can be considered sustainable

and safe for Chinese PIC in Hong Kong.

Studies on the effects of telepsychiatry for

incarcerated populations are relatively scarce; however, the results of

our study are also consistent with studies of telepsychiatry in

populations that were not involved with the correctional system. In a

randomised controlled study in Canada, 495 patients were assigned at

random to be examined face-to-face or by telepsychiatry.14 Psychiatric consultations and follow-ups delivered by

telepsychiatry produced clinical outcomes equivalent to those achieved

when the service was provided face-to-face.14

This result suggests that psychiatric consultation and short-term

follow-up can be as effective when delivered by telepsychiatry as when

provided face-to-face. Another study evaluating the effectiveness of

telepsychiatry in relation to cognitive changes in patients with dementia

revealed that changes in the Mini-Mental State Examination score were not

significantly different between patients receiving teleconsultations and

those receiving clinic-based face-to-face consultations.15 This finding suggest that telepsychiatry may be a

useful alternative to face-to-face clinical visits for treatment of a wide

range of patient groups, including patients with dementia. Research has

shown that there is an association between dementia and criminal offences

and that the use of telepsychiatry might be extended to PIC with dementia

in Hong Kong.16

Our study has several limitations. First, the

sample size of the intervention group was small. Most enrolled patients

served short sentences but had long follow-up intervals, because we

recruited stable patients. Although the study duration was 2 years, only

29 out of 86 intervention participants had at least two psychiatric

teleconsultations for comparison within the intervention group. Second,

recruitment of potential telepsychiatry participants was limited to stable

Chinese male psychiatric out-patients. Therefore, the sample may be

affected by self-selection bias, because PICs volunteered to participate

in telepsychiatry. This restricted sample also limits the generalisability

of the results. Third, the mean time between the consultation and

completion of the C-GHQ-12 was not recorded for intervention or control

groups. Differences in this time interval may affect the pre-post

difference in C-GHQ-12 score for the groups. We also did not collect data

on the follow-up interval between the first and second psychiatric

teleconsultations for the intervention group. This follow-up interval may

affect the C-GHQ-12 score and the satisfaction on psychiatric

teleconsultation. Fourth, the mean on-air time duration of psychiatric

teleconsultations was 6.33 minutes; however, we did not measure the

duration of face-to-face consultations for comparison between the two

groups. The duration of consultation may have an effect on the outcome

scores and patient satisfaction. Last, the study lacked robust clinical

outcome measures and the satisfactory questionnaire adopted in this study

had not been validated. Despite the limitations of this study, the results

suggest that psychiatric teleconsultations are a sustainable and safe

alternative to face-to-face consultations for stable Chinese male

psychiatric out-patients in custody. The use of psychiatric

teleconsultations has potential in other populations of PICs, such as

female PICs or elderly PICs, but further research is required to

investigate psychiatric teleconsultations for these populations.

Further research is required to examine the full

potential of telepsychiatry among PICs in Hong Kong. In future studies,

female patients should be recruited, to assess any sex-based differences.

In addition, the scale of future studies using telepsychiatry can be

increased by setting up more stations at CSD institutions and at other

SOPCs in the Hospital Authority. Clinical outcomes such as symptom

severity and psychological functioning of the patients could be assessed.

Given the increasing number of older PICs in Hong Kong, recruitment of

older patients could be considered for further study. It would be

worthwhile to perform a future study with a larger sample size and with

participants receiving a greater number of psychiatric teleconsultations,

in order to further support the sustainability of psychiatric

teleconsultations.

A cost analysis for psychiatric teleconsultation

was beyond the scope of the present study. However, a systematic review of

137 telemedicine services in hospital facilities revealed that one of the

key reasons for introducing telemedicine was cost reduction.17 Similar cost-saving conclusions have been reported in

two studies in Hong Kong related to dementia and community geriatric

services.11 12 In future studies, cost analysis of psychiatric

teleconsultation including direct, indirect, and hidden costs could be

calculated for further exploring the effectiveness of psychiatric

teleconsultation.

Conclusions

Telepsychiatry appears to be an acceptable approach

for providing out-patient psychiatric care for stable Chinese male PICs in

Hong Kong. Telepsychiatry can be considered a sustainable and safe

alternative to face-to-face consultations, with a comparable standard of

care. Moreover, the intrinsic problems of embarrassment and stigmatisation

caused to PICs, the risk that PICs might abscond, and the safety of the

general public are all addressed by this promising alternative mode of

psychiatric care for stable Chinese male PICs. Telepsychiatry is likely to

show similar benefits for Chinese female PICs and PICs in other age-groups, such as older adults, but further research is required to confirm

this.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to

the concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation

of data, drafting and critical revision for important intellectual content

of the article.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Dr CK Tung, Dr CF

Tsui, Mr KW Chung, Mr Kenny Wong, Dr NM Kwong, and all the mental health

professionals and CSD staff who have assisted in the design and

implementation of this study. We would also like to acknowledge the study

participants who had kindly participated in the present study.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility

for its accuracy and integrity. The research was presented in part in the

Hospital Authority Convention 2017, 16 May 2017, Hong Kong.

Ethical approval

Approval for conducting the study was granted by

the Research and Ethics Committee of the New Territories West Cluster of

the Hospital Authority and the Research and Ethics Committee of the

Correctional Services Department. The principles outlined in the

Declaration of Helsinki were followed in the conduction of this study.

References

1. Gray LC, Edirippulige S, Smith AC, et

al. Telehealth for nursing homes: the utilization of specialist services

for residential care. J Telemed Telecare 2012;18:142-6. Crossref

2. Grady B, Myers KM, Nelson EL, et al.

Evidence-based practice for telemental health. Telemed e-Health

2011;17:131-48. Crossref

3. WHO Global Observatory for eHealth.

2010. Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in Member States:

report on the second global survey on eHealth. Geneva: World Health

Organization. Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44497.

Accessed 1 Jan 2018.

4. McLaren P. Telemedicine and telecare:

what can it offer mental health services? Adv Psychiatr Treat

2003;9:54-61. Crossref

5. Telemedicine can Reduce Correctional

Health Care Costs: An Evaluation of a Prison Telemedicine Network. US

Department of Justice; 1999.

6. Hjelm NM. Telemedicine: academic and

professional aspects. Hong Kong Med J 1998;4:289-92.

7. International Statistical Classification

of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision. Geneva, World

Health Organization; 1992.

8. Chan DW. The Chinese version of the

General Health Questionnaire: does language make a difference? Psychol Med

1985;15:147-55. Crossref

9. Goldberg DP. The Detection of

Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. London: Oxford University Press;

1972.

10. Goldberg D, Williams P. A User’s Guide

to the General Health Questionnaire. London: NFER; 1988.

11. Tang WK, Chiu H, Woo J, Hjelm M, Hui

E. Telepsychiatry in psychogeriatric service: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr

Psychiatry 2001;16:88-93. Crossref

12. Poon P, Hui E, Dai D, Kwok T, Woo J.

Cognitive intervention for community-dwelling older persons with memory

problems: telemedicine versus face-to-face treatment. Int J Geriatr

Psychiatry 2005;20:285-6. Crossref

13. Farabee D, Calhoun S, Veliz R. An

experimental comparison of telepsychiatry and conventional psychiatry for

parolees. Psychiatr Serv 2016;67:562-5. Crossref

14. O’Reilly R, Bishop J, Maddox K,

Hutchinson L, Fisman M, Takhar J. Is telepsychiatry equivalent to

face-to-face psychiatry? Results from a randomized controlled equivalence

trial. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58:836-43. Crossref

15. Kim H, Jhoo JH, Jang JW. The effect of

telemedicine on cognitive decline in patients with dementia. J Telemed

Telecare 2017;23:149-54. Crossref

16. Liljegren M, Naasan G, Temlett J, et

al. Criminal behavior in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease.

JAMA Neurol 2015;72:295-300. Crossref

17. AlDossary S, Martin-Khan MG, Bradford

NK, Smith AC. A systematic review of the methodologies used to evaluate

telemedicine service initiatives in hospital facilities. Int J Med Inform

2017;97:171-94. Crossref