Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Aug;24(4):340–9 | Epub 2 Mar 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176870

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Genetic basis of channelopathies and cardiomyopathies

in Hong Kong Chinese patients: a 10-year regional laboratory experience

Chloe M Mak1; Sammy PL Chen2;

NS Mok3; WK Siu2; Hencher HC Lee2; CK

Ching2; PT Tsui3; NC Fong4; YP Yuen2;

WT Poon2; CY Law2; YK Chong2; YW Chan2;

TC Yung5; Katherine YY Fan6; CW Lam7

1 Chemical Pathology Laboratory, Kowloon

West Cluster Laboratory Genetic Service, Department of Pathology, Princess

Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

2 Department of Pathology, Princess

Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

3 Department of Medicine, Princess

Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

4 Department of Paediatrics and

Adolescent Medicine, Princess Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

5 Department of Paediatric Cardiology,

Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

6 Department of Cardiac Medicine,

Grantham Hospital, Wong Chuk Hang, Hong Kong

7 Department of Pathology, The

University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Chloe M Mak (makm@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Hereditary

channelopathies and cardiomyopathies are potentially lethal and are

clinically and genetically heterogeneous, involving at least 90 genes.

Genetic testing can provide an accurate diagnosis, guide treatment, and

enable cascade screening. The genetic basis among the Hong Kong Chinese

population is largely unknown. We aimed to report on 28 unrelated

patients with positive genetic findings detected from January 2006 to

December 2015.

Methods: Sanger sequencing was

performed for 28 unrelated patients with a clinical diagnosis of

channelopathies or cardiomyopathies, testing for the following genes: KCNQ1,

KCNH2, KCNE1, KCNE2, and SCN5A, for long

QT syndrome; SCN5A for Brugada syndrome; RYR2 for

catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; MYH7 and

MYBPC3 for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LMNA for dilated

cardiomyopathy; and PKP2 and DSP for arrhythmogenic

right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy.

Results: The study included 17 male and

11 female patients; their mean age at diagnosis was 39 years (range, 1-80

years). The major clinical presentations included syncope, palpitations,

and abnormal electrocardiography findings. A family history was present

in 13 (46%) patients. There were 26 different heterozygous mutations

detected, of which six were novel—two in SCN5A

(NM_198056.2:c.429del and c.2024-11T>A), two in MYBPC3

(NM_000256.3:c.906-22G>A and c.2105_2106del), and two in LMNA

(NM_170707.3:c.73C>A and c.1209_1213dup).

Conclusions: We characterised the genetic heterogeneity in channelopathies and cardiomyopathies among Hong Kong Chinese patients in a 10-year case

series. Correct interpretation of genetic findings is difficult and

requires expertise and experience. Caution regarding issues of

non-penetrance, variable expressivity, phenotype-genotype correlation,

susceptibility risk, and digenic inheritance is necessary

for genetic counselling and cascade screening.

New knowledge added by this study

- We characterised the genetic heterogeneity in channelopathies and cardiomyopathies among Hong Kong Chinese patients and described 26 mutations with six novel variants.

- This is the first case series of cardiac genetics in Hong Kong.

- This study provides genetic information for variant interpretation and insight into the clinical application of genetic testing for channelopathies and cardiomyopathies.

Introduction

Cardiac genetics is evolving rapidly and many new

insights have recently been achieved. Genetic causes are found in various

potentially lethal channelopathies and cardiomyopathies including long and

short QT syndrome (LQTS and SQTS), Brugada syndrome, catecholaminergic

polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

(HCM), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), arrhythmogenic right ventricular

dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C), Barth syndrome, and left ventricular

non-compaction.1 Knowledge of

genetics deepens the understanding of pathophysiology and remarkably

changes the diagnosis, treatment, and genetic counselling for recurrence

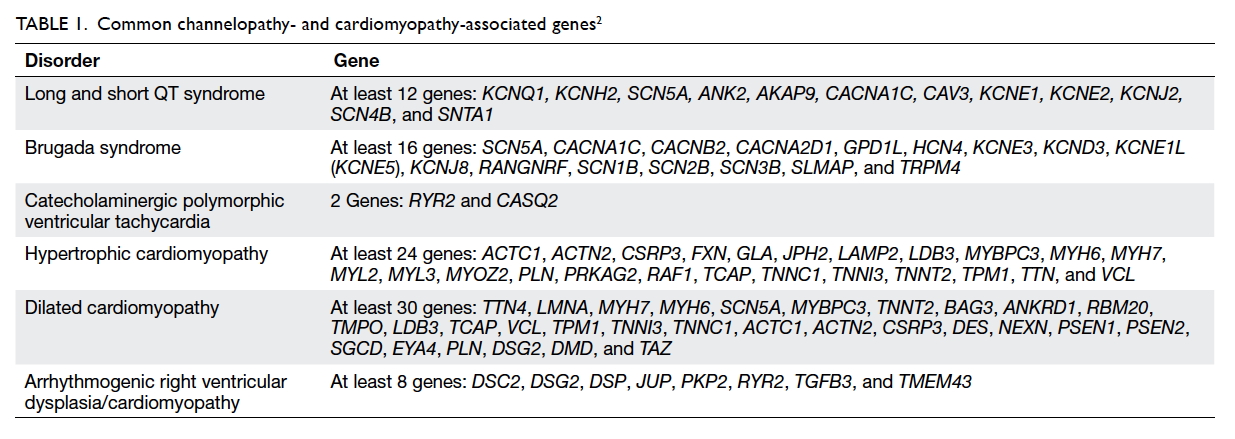

risk and family planning. This group is highly genetically heterogeneous (Table 12).

The genetic basis of inherited cardiac diseases in

the Hong Kong Chinese population is largely unknown. The Princess Margaret

Hospital provides a comprehensive cardiac genetic service. We conducted

this study to review the clinical and genetic findings of 28 unrelated

positive cases encountered between January 2006 and December 2015.

Methods

Diagnosis of the cardiac conditions was based on

clinical assessments by a cardiologist and practice guidelines.3 4 5 The patients were referred by cardiologists from

various public hospitals for genetic analysis. Only patients with positive

genetic findings are reported in this study. There were seven patients

with LQTS, two with Brugada syndrome, two with CPVT, nine with HCM, four

with DCM, and four with ARVD/C. Local ethics board approval was obtained.

Peripheral blood samples were collected from the proband after informed

consent was obtained. Genomic DNA was extracted using a QIAamp Blood Kit

(Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The coding exons and the flanking introns (10

bp) of each gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction. The primer

sequences and protocol are available on request. Sanger sequencing was

performed in the following order and stopped once a positive finding was

detected: KCNQ1, KCNH2, KCNE1, KCNE2, and

SCN5A for LQTS; SCN5A for Brugada syndrome; RYR2

for CPVT; MYH7 and MYBPC3 for HCM; LMNA for DCM;

and PKP2 and DSP for ARVD/C. The order was based on

prevalence according to the literature and local experience. All coding

exons were amplified for each gene except selected exons 3, 8, 14, 45, 46,

47, 49, 88, 89, 90, 93, 96, 97, 100, 101, and 103 for RYR2.6 The GenBank accession numbers are shown in Table

2. The pathogenicity of novel missense variants was analysed by

Alamut Visual (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France) with Polymorphism

Phenotyping v2 (PolyPhen-2), Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT),

MutationTaster, and Assessing Pathogenicity Probability in Arrhythmia by

Integrating Statistical Evidence (APPRAISE,

https://cardiodb.org/APPRAISE/) and that of novel splicing variants by

Splice Site Finder-like, MaxEntScan, NNSPLIC, GeneSplicer, and Human

Splicing Finder, wherever appropriate. Splicing variants were considered

to be damaging if there was a >10% lower score when compared with the

wild-type prediction. Allele frequencies among populations were referred

to the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC;

http://exac.broadinstitute.org/).

Results

During the 10-year study period more than 90 patients with

channelopathies or cardiomyopathies were referred for genetic analysis.

Among them, 28 unrelated patients had positive genetic results, comprising

17 males and 11 females. Their mean age at diagnosis was 39 years (range,

1-80 years). The major clinical presentations included syncope,

palpitations, and abnormal electrocardiography (ECG) findings. Four

patients were asymptomatic and were diagnosed following an incidental

abnormal finding related to other medical issues. A family history was

present in only 13 (46%) patients. All detected mutations were

heterozygous, and 26 different heterozygous mutations were detected. These

encompassed 11 missense, two nonsense, and five splicing mutations, as

well as eight small insertions and deletions. There were six novel

mutations—two in SCN5A (NM_198056.2:c.429del and c.2024-11T>A),

two in MYBPC3 (NM_000256.3:c.906-22G>A and c.2105_2106del), and

two in LMNA (NM_170707.3:c.73C>A and c.1209_1213dup) [Table

3]. All were considered pathogenic or likely pathogenic according to

the Practice Guidelines for the Evaluation of Pathogenicity and the

Reporting of Sequence Variants in Clinical Molecular Genetics by the

Association for Clinical Genetic Science.7

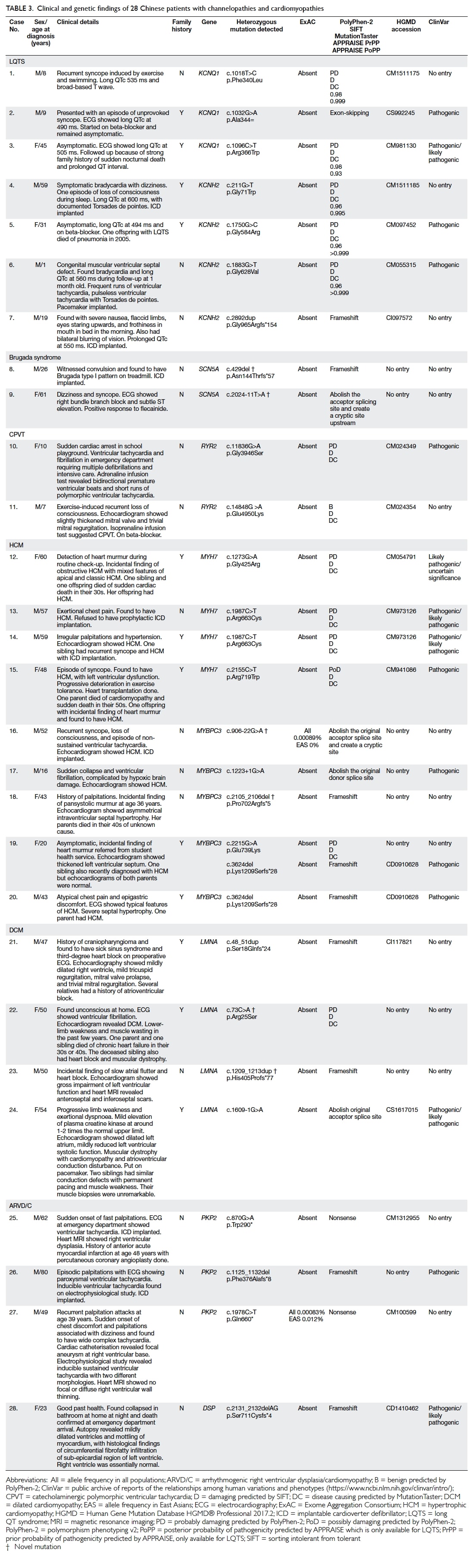

Further clinical details and genotypes are shown in Table

3.

Table 3. Clinical and genetic findings of 28 Chinese patients with channelopathies and cardiomyopathies

There were seven patients with LQTS, two with

Brugada syndrome, two with CPVT, nine with HCM, four with DCM, and four

with ARVD/C. Three patients with LQTS had mutations in KCNQ1

(cases 1-3) and four had mutations in KCNH2 (cases 4-7). Two

patients (cases 8 and 9) with Brugada syndrome had mutations in SCN5A,

including two novel mutations. Two patients (cases 10 and 11) with CPVT

had mutations in RYR2. Four patients with HCM (cases 12-15) had MYH7

mutations and five (cases 16-20) had MYBPC3 mutations, including

two novel mutations. Four patients with DCM (cases 21-24) had LMNA

mutations, including two novel mutations. Finally, three patients with

ARVD/C had PKP2 mutations (cases 25-27) and one had a DSP

mutation (case 28).

Discussion

This is the first report of a cardiac genetic case

series among Hong Kong Chinese patients with channelopathies and

cardiomyopathies. A total of 28 patients are reported, and 26 different

mutations and six novel mutations have been identified. Wide genetic

diversity is observed, with no common mutation found. Hereditary

channelopathies and cardiomyopathies are mainly inherited in an autosomal

dominant manner. Mutations can be either inherited or de novo. Risk to

proband sibling(s) and first-degree relatives depends on the genetic

status of the parents. Offspring of the proband have a 50% risk of

inheriting the mutation. Siblings of the proband have the same risk if the

mutation is transmitted from either parent. Patients carrying a mutation

of these sudden arrhythmia death syndromes show incomplete penetrance. In

general, a mutation carrier will show symptoms/signs in 80% of those with

CPVT, 20% to 50% of ARVD/C patients, 18% to 63% of LQTS patients, 80% to

94% of SQTS patients, and 80% of patients with Brugada syndrome who have

abnormal ECG findings when challenged with a sodium channel blocker.8 No exact figure is available for HCM. The data could be

more specific if a particular mutation was considered alongside clinical

findings and family history. Pre-symptomatic testing of at-risk family

members cannot be used to predict age of onset, severity, type of

symptoms, or rate of progression. Detailed clinical, ECG, and genetic

characterisation of affected and unaffected family members is helpful.

Long QT syndrome

Long QT syndrome is genetically heterogeneous, with

at least 12 genes involved. Mutations in the four genes, KCNQ1, KCNH2,

KCNE1, and KCNE2, are detected in 46%, 38%, 2%, and 1% of

affected patients, respectively.8 A

small proportion of patients (3%) have double heterozygous mutations in

more than one disease loci.9

Specific arrhythmogenic triggers are associated with a particular subtype,

such as exertion, swimming, and near-drowning for LQT1; auditory triggers

and cardiac events occurring in the postpartum period for LQT2; and

cardiac events during sleep or at rest for LQT3. Three patients had KCNQ1

mutations. Case 1 had recurrent syncope induced by exercise and swimming,

but genetic testing confirmed LQTS type 1. Other patients had no specific

provoking factor. LQTS type 2 caused by KCNH2 mutations accounts

for about 38% of all LQTS.8 Four patients (cases 4-7) carried KCNH2

mutations and two (cases 4 and 6) presented with Torsades de pointes and

one (case 7) had survived cardiac arrest requiring an implantable

cardioverter defibrillator. Case 6 was the youngest patient, presenting at age 1 year. Genotype-guided treatment in LQTS is recommended and

LQT1 responds best to beta-blockers.10

11

Brugada syndrome

Brugada syndrome is characterised by cardiac

conduction abnormalities (ST-segment abnormalities in leads V1-V3 on ECG

and a high risk for ventricular arrhythmias) that can result in sudden

death. The Shanghai Score System has been recently published for the

diagnosis of Brugada syndrome.12 13 The prevalence of Brugada

syndrome or its characteristic ECG pattern is reportedly higher among

Asians, such as Japanese (0.14%-1.22%).14

15 16

17

Brugada syndrome is genetically heterogeneous and

can be attributed to defects in at least 23 genes at the time of

reporting.8 Mutations in SCN5A

are detected in 11% to 14% of affected individuals in Japan and <10% in

Taiwan where mutations in CACNA1C account for 1% to 7%.18 Approximately 65% to 70% of patients remain

genetically undiagnosed. Expressivity is variable and penetrance is

incomplete and low.

Conventionally, Brugada syndrome has been described

as a monogenic disease that has autosomal dominant inheritance with

incomplete penetrance; it is caused by rare genetic variants with a large

effect size. Most individuals diagnosed with Brugada syndrome have an

affected parent. The proportion of cases caused by a de-novo mutation is

approximately 1%. Recent studies indicate that genetic inheritance is

likely more complex, and models of an oligogenic disorder or

susceptibility risk/genetic predisposition have been suggested.19 20 21 22

Among the two patients in this series, none had a

positive family history. Symptoms were more non-specific, such as

palpitation and syncope. It is noteworthy that convulsion can be a

presentation of channelopathies (case 8). Clinical suspicion should be

higher with more specific investigations, such as exercise-stress ECG and

flecainide challenge tests, are required in order to reveal the real

culprit. Sudden cardiac death can be the first presenting symptom in

Brugada syndrome.

Two novel mutations are described in SCN5A:

c.429del and c.2024-11T>A. The former is predicted to cause a

frameshift and premature protein truncation. The latter is predicted to

abolish the acceptor splice site and create a cryptic site upstream. At

the time of reporting, both are absent from controls in the Exome

Sequencing Project, 1000 Genomes Project, and ExAC. SCN5A

mutations can cause either LQTS or Brugada syndrome.

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular

tachycardia can present with syncope and sudden death during physical

exertion or emotion, due to catecholamine-induced bidirectional

ventricular tachycardia, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or

ventricular fibrillation. The reported mean age of onset is between 7 and

12 years.8 Exercise stress testing

or an adrenaline provocation test may induce ventricular arrhythmia and

enable a clinical diagnosis. About half of these cases are related to a

dominantly inherited RYR2 gene mutation, with a small proportion

(1%-2%) related to recessively inherited CASQ2 gene mutations. RYR2

is a large gene with 105 exons. Tier testing has been proposed by

Medeiros-Domingo et al.6 First-tier

RYR2 genetic testing of the 16 selected exons allows

identification of about 65% of CPVT cases. There were two paediatric CPVT

patients (cases 10 and 11) in our series, with two known disease-causing

mutations detected, namely NM_001035.2(RYR2):c.11836G>A

(p.Gly3946Ser)23 24 25 26 and c.14848G>A (p.Glu4950Lys).23 24 Both

mutations were detected in first-tier screening.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is the most prevalent

hereditary cardiac disease, causing about one third of sudden cardiac

deaths in young athletes. Its prevalence in China is approximately 1 in

1250.27 The clinical

manifestations are markedly variable, ranging from asymptomatic to sudden

cardiac death. Genetic testing provides an accurate diagnosis in the

probands and enables screening of asymptomatic family members. Although

the genetic background of HCM is heterogeneous, involving at least 30

genes, MYH7 and MYBPC3 are the most common and each

accounts for approximately 40%.8

Nine patients with HCM are reported here: four had

known MYH7 mutations and five had MYBPC3 mutations,

including two novel mutations. NM_000256.3:c.906-22G>A was detected in

case 16 and was a novel variant. Neither population frequency nor known

pathogenicity have been reported. In-silico analysis showed creation of a

novel acceptor site and insertion of 20 nucleotides into exon 10. This

conceivably would lead to a frameshift and premature protein termination.

Exon 10 of MYBPC3 is a microexon in which the stability of its

original splicing site is easily disrupted by intronic variants. A similar

mutation has been reported as c.906-36G>A.28

Nonetheless, cDNA analysis was not performed. NM_000256.3(MYBPC3):c.1223+1G>A

at the critical canonical +1 splice site is also novel. In addition, other

known disease-causing splicing mutations affecting the same nucleotide

have been reported.26 29 30 Case 19

had two variants detected in MYBPC3 (c.2215G>A and c.3624del).

The small deletion c.3624del is a mutation known to cause HCM in the

Chinese population31 and predicted

to cause a frameshift and premature termination of the protein. The

missense variant c.2215G>A is as yet unreported and is predicted by

in-silico analyses to cause an amino acid change from glutamate to lysine

at codon 739 and probably damage. At the time of reporting, the variant is

absent from controls in the Exome Sequencing Project, 1000 Genomes

Project, and ExAC databases. This variant is considered to have uncertain

significance. The mother of the patient in case 19 was available for

testing. She was 48 years old at the time of genetic testing,

asymptomatic, and heterozygous for c.3624del only. Hence, the two variants

c.2215G>A and c.3624del of MYBPC3 were in-trans in the patient

and elder brother of the patient in case 19. Both had a more severe form

of HCM, with a younger onset.

Dilated cardiomyopathy

Familial DCM is a group of genetically

heterogeneous disorders. Laminopathy can manifest as several allelic

disorders affecting muscle, nerve, adipose, and vascular tissues; one of

them is cardiomyopathy, dilated 1A. We identified four patients with DCM,

two of whom also had proximal muscle weakness. Two novel mutations in LMNA

were detected (c.73C>A and c.1209_1213dup). NM_005572.3(LMNA):c.73C>A

is a novel variant that is predicted to be deleterious by SIFT, probably

causing damage according to PolyPhen-2 and disease-causing according to

MutationTaster. Other missense mutations have been reported in the same

amino acid codon.32 33 34

NM_005572.3(LMNA):c.1609-1G>A is predicted to significantly

affect splicing by in-silico analysis. At the time of reporting, all

variants are absent from controls in the Exome Sequencing Project, 1000

Genomes Project, and ExAC. In case 22 with NM_005572.3(LMNA):c.73C>A,

one of the parents died of chronic heart failure in the fourth decade of

life, and one sibling died of heart block and chronic heart failure with a

diagnosis of muscular dystrophy at age 38 years. Nonetheless, there was no

sample left for genotyping.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular

dysplasia/cardiomyopathy

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular

dysplasia/cardiomyopathy is associated with fibrofatty replacement of

cardiomyocytes, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death.

Although the right ventricle is primarily affected in this condition,

left-dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy has also been described, and

mutations have been identified in DSP as well as in other genes.35 Four patients are reported here,

with three having mutations in PKP2 and one in DSP.

Interestingly, the patient in case 26 presented at age 80 years with

episodic palpitations. His ECG results showed paroxysmal ventricular

tachycardia. He had a deletion in PKP2, c.1125_1132del

(p.Phe376Alafs*8), resulting in a truncated incomplete protein product.

Age of onset in patients with PKP2 mutations is older than that of

the patient with DSP mutation. The latter patient (case 28) died

at age 23 years, with sudden collapse as the first presentation.

Primary arrhythmogenic disorders including

LQTS/SQTS, CPVT, Brugada syndrome, and cardiomyopathies account for about

one third of sudden cardiac deaths in the young.36

Identification of a pathogenic variant can solve the diagnostic mystery,

provide relief to the family, and enable family screening and counselling

for other at-risk family members. In some developed countries, molecular

autopsy is an essential part of a formal forensic investigation in

unexplained sudden death.37 We

support the implementation of molecular autopsy in routine autopsy

investigation of sudden cardiac death victims. Our group has conducted the

first local prospective study to determine the prevalence and types of

sudden arrhythmia death syndrome underlying sudden cardiac death among

local young victims through clinical and molecular autopsy of sudden

cardiac death victims and clinical and genetic evaluation of their

first-degree relatives (http://www.sadshk.org/en/medical_research.php).

Such data can serve as the groundwork for the feasibility of

implementation of such investigations in Hong Kong.

Genetic tests for cardiac conditions can aid

diagnosis and guide treatment. Nonetheless, there are limitations that

complicate the translational use of genetic results in patient care, such

as incomplete penetrance, variable expressivity, and findings of variants

of uncertain significance. In addition, since the genetic heterogeneity is

large among cardiomyopathies and channelopathies and more genes are yet to

be discovered, a negative genetic finding does not necessarily exclude a

genetic basis of disease in patients.

Major limitations of the current study include its

small sample size, incomplete family data for co-segregation study, and

lack of functional study of novel variants. We observed a lower rate of

use of genetic tests in early years that might have been due to

insufficient awareness among clinicians about the clinical usefulness of

such tests for channelopathies and cardiomyopathies. Clinical indications

published in an expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing

for channelopathies and cardiomyopathies from the Heart Rhythm Society and

European Heart Rhythm Association provide a good reference to determine

when a genetic test should be requested.5

In our hospital, referral information can be accessed on

http://kwcpath.home/genetics/ and more information about genetic service

provision in public hospitals is available in the Hong Kong Hospital

Authority Genetic Test Formulary (http://gtf.home/). A comprehensive

system of cardiac genetics service is required for an efficient referral

system, resource funding, training, and appropriate long-term follow-up.

Conclusions

We present the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of 28 unrelated Hong Kong Chinese patients diagnosed across a 10-year period. For each disease entity, it was beyond our reach in the past decade to exhaustively screen for all known genes. We therefore focus on the most common ones when investigating cardiac genetics. Even so, genetic analysis can provide an accurate diagnosis

and is of utmost importance for the management of patients and their families. Non-penetrance, variable expressivity, phenotype-genotype correlation, susceptibility risk, and digenic inheritance have been reported. Genetic testing also allows for genetic counselling on the recurrence risk. Correct interpretation of genetic findings for careful genetic counselling requires professional expertise with relevant experience in both clinical medicine and molecular genetics. Next-generation sequencing will improve diagnostic performance in this genetically heterogeneous group of channelopathies and cardiomyopathies, and could become a mainstay diagnostic tool.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the concept or design of this study; acquisition of data; analysis or interpretation of data; drafting of the article; and critical revision for important intellectual content.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Ethical approval

Local ethical approval of this study was obtained (KW/EX/09-155).

References

1. Herman A, Bennett MT, Chakrabarti S,

Krahn AD. Life threatening causes of syncope: channelopathies and

cardiomyopathies. Auton Neurosci 2014;184:53-9. Crossref

2. Ackerman MJ, Marcou CA, Tester DJ.

Personalized medicine: genetic diagnosis for inherited

cardiomyopathies/channelopathies. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed)

2013;66:298-307. Crossref

3. Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, et al.

HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management

of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed

by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in

June 2013. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:1932-63. Crossref

4. Authors/Task Force members, Elliott PM,

Anastasakis A, et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on diagnosis and management of

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the task force for the diagnosis and

management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of the European Society of

Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2733-79. Crossref

5. Ackerman MJ, Priori SG, Willems S, et

al. HRS/EHRA expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing

for the channelopathies and cardiomyopathies: this document was developed

as a partnership between the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the European

Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Europace 2011;13:1077-109. Crossref

6. Medeiros-Domingo A, Bhuiyan ZA, Tester

DJ, et al. The RYR2-encoded ryanodine receptor/calcium release

channel in patients diagnosed previously with either catecholaminergic

polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or genotype negative, exercise-induced

long QT syndrome: a comprehensive open reading frame mutational analysis.

J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:2065-74. Crossref

7. Wallis Y, Payne S, McAnulty C, et al.

Practice guidelines for the evaluation of pathogenicity and the reporting

of sequence variants in clinical molecular genetics. Association for

Clinical Genetic Science; 2013.

8. Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace

SE, editors. GeneReviews [internet]. Seattle (WA): GeneReviews; 1993.

Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1116/. Accessed 19

Feb 2018.

9. Bokil NJ, Baisden JM, Radford DJ,

Summers KM. Molecular genetics of long QT syndrome. Mol Genet Metab

2010;101:1-8. Crossref

10. Giudicessi JR, Ackerman MJ. Genotype-

and phenotype-guided management of congenital long QT syndrome. Curr Probl

Cardiol 2013;38:417-55. Crossref

11. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ,

et al. Association of long QT syndrome loci and cardiac events among

patients treated with beta-blockers. JAMA 2004;292:1341-4. Crossref

12. Antzelevitch C, Yan GX, Ackerman MJ,

et al. J-Wave syndromes expert consensus conference report: emerging

concepts and gaps in knowledge. Europace 2017;19:665-94.

13. Antzelevitch C, Yan GX, Ackerman MJ,

et al. J-Wave syndromes expert consensus conference report: emerging

concepts and gaps in knowledge. J Arrhythm 2016;32:315-39. Crossref

14. Furuhashi M, Uno K, Tsuchihashi K, et

al. Prevalence of asymptomatic ST segment elevation in right precordial

leads with right bundle branch block (Brugada-type ST shift) among the

general Japanese population. Heart 2001;86:161-6. Crossref

15. Matsuo K, Akahoshi M, Nakashima E, et

al. The prevalence, incidence and prognostic value of the Brugada-type

electrocardiogram: a population-based study of four decades. J Am Coll

Cardiol 2001;38:765-70. Crossref

16. Sakabe M, Fujiki A, Tani M, Nishida K,

Mizumaki K, Inoue H. Proportion and prognosis of healthy people with coved

or saddle-back type ST segment elevation in the right precordial leads

during 10 years follow-up. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1488-93. Crossref

17. Hiraoka M. Brugada syndrome in Japan.

Circ J 2007;71 Suppl A:A61-8.

18. Juang JM, Tsai CT, Lin LY, et al.

Unique clinical characteristics and SCN5A mutations in patients

with Brugada syndrome in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2015;114:620-6. Crossref

19. Bezzina CR, Barc J, Mizusawa Y, et al.

Common variants at SCN5A-SCN10A and HEY2 are associated

with Brugada syndrome, a rare disease with high risk of sudden cardiac

death. Nat Genet 2013;45:1044-9. Crossref

20. Behr ER, Savio-Galimberti E, Barc J,

et al. Role of common and rare variants in SCN10A: results from

the Brugada syndrome QRS locus gene discovery collaborative study.

Cardiovasc Res 2015;106:520-9. Crossref

21. Gourraud JB, Barc J, Thollet A, et al.

The Brugada syndrome: a rare arrhythmia disorder with complex inheritance.

Front Cardiovasc Med 2016;3:9. Crossref

22. Juang JJ, Horie M. Genetics of Brugada

syndrome. J Arrhythm 2016;32:418-25. Crossref

23. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Memmi M, et

al. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with

catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation

2002;106:69-74. Crossref

24. Jabbari J, Jabbari R, Nielsen MW, et

al. New exome data question the pathogenicity of genetic variants

previously associated with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular

tachycardia. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2013;6:481-9. Crossref

25. Kawamura M, Ohno S, Naiki N, et al.

Genetic background of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular

tachycardia in Japan. Circ J 2013;77:1705-13. Crossref

26. Xiong HY, Alipanahi B, Lee LJ, et al.

RNA splicing. The human splicing code reveals new insights into the

genetic determinants of disease. Science 2015;347:1254806. Crossref

27. Zou Y, Song L, Wang Z, et al.

Prevalence of idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in China: a

population-based echocardiographic analysis of 8080 adults. Am J Med

2004;116:14-8. Crossref

28. Frank-Hansen R, Page SP, Syrris P,

McKenna WJ, Christiansen M, Andersen PS. Micro-exons of the cardiac myosin

binding protein C gene: flanking introns contain a disproportionately

large number of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations. Eur J Hum Genet

2008;16:1062-9. Crossref

29. Millat G, Bouvagnet P, Chevalier P, et

al. Prevalence and spectrum of mutations in a cohort of 192 unrelated

patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Med Genet 2010;53:261-7.

Crossref

30. Waldmuller S, Muller M, Rackebrandt K,

et al. Array-based resequencing assay for mutations causing hypertrophic

cardiomyopathy. Clin Chem 2008;54:682-7. Crossref

31. Liu X, Jiang T, Piao C, et al.

Screening mutations of MYBPC3 in 114 unrelated patients with

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by targeted capture and next-generation

sequencing. Sci Rep 2015;5:11411. Crossref

32. Narula N, Favalli V, Tarantino P, et

al. Quantitative expression of the mutated lamin A/C gene in patients with

cardiolaminopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1916-20. Crossref

33. Vytopil M, Benedetti S, Ricci E, et

al. Mutation analysis of the lamin A/C gene (LMNA) among patients

with different cardiomuscular phenotypes. J Med Genet 2003;40:e132. Crossref

34. Yuan WL, Huang CY, Wang JF, et al.

R25G mutation in exon 1 of LMNA gene is associated with dilated

cardiomyopathy and limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 1B. Chin Med J (Engl)

2009;122:2840-5.

35. Sen-Chowdhry S, Syrris P, Prasad SK,

et al. Left-dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: an under-recognized

clinical entity. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:2175-87. Crossref

36. Semsarian C, Hamilton RM. Key role of

the molecular autopsy in sudden unexpected death. Heart Rhythm

2012;9:145-50. Crossref

37. Torkamani A, Muse ED, Spencer EG, et

al. Molecular autopsy for sudden unexpected death. JAMA 2016;316:1492-4. Crossref