Hong Kong Med J 2018 Apr;24(2):98–106 | Epub 9 Feb 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176871

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Outcomes of a pharmacist-led medication review

programme for hospitalised elderly patients

Patrick KC Chiu, FRCP (Glasg), FHKAM (Medicine)1;

Angela WK Lee, MPharm, RPharmS (Great Britain)2; Tammy YW See,

MClinPharm, RPharmS (Great Britain)2; Felix HW Chan, FRCP

(Edin, Glasg, Irel), FHKAM (Medicine)1

1 Geriatric Medical Unit, Grantham

Hospital, Wong Chuk Hang, Hong Kong

2 Pharmacy, Grantham Hospital, Wong Chuk

Hang, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Patrick KC Chiu (chiukc@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Elderly patients

are at risk of drug-related problems. This study aimed to determine

whether a pharmacist-led medication review programme could reduce

inappropriate medications and hospital readmissions among geriatric

in-patients in Hong Kong.

Methods: This prospective

controlled study was conducted in a geriatric unit of a regional

hospital in Hong Kong. The study period was from December 2013 to

September 2014. Two hundred and twelve patients were allocated to

receive either routine care (104) or pharmacist intervention (108) that

included medication reconciliation, medication review, and medication

counselling. Medication appropriateness was assessed by a pharmacist

using the Medication Appropriateness Index. Recommendations made by the

pharmacist were communicated to physicians.

Results: At hospital admission,

51.9% of intervention and 58.7% of control patients had at least one

inappropriate medication (P=0.319). Unintended discrepancy applied in

19.4% of intervention patients of which 90.7% were due to omissions.

Following pharmacist recommendations, 60 of 93 medication reviews and 32

of 41 medication reconciliations (68.7%) were accepted by physicians and

implemented. After the program and at discharge, the proportion of

subjects with inappropriate medications in the intervention group was

significantly lower than that in the control group (28.0% vs 56.4%;

P<0.001). The unplanned hospital readmission rate 1 month after

discharge was significantly lower in the intervention group than that in

the control group (13.2% vs 29.1%; P=0.005). Overall, 98.0% of

intervention subjects were satisfied with the programme. There were no

differences in the length of hospital stay, number of emergency

department visits, or mortality rate between the intervention and

control groups.

Conclusions: A pharmacist-led

medication review programme that was supported by geriatricians

significantly reduced the number of inappropriate medications and

unplanned hospital readmissions among geriatric in-patients.

New knowledge added by this study

- This is the first prospective controlled study of the effect of a pharmacist-led medication review programme on medication use and health services utilisation among hospitalised Chinese elderly patients in Hong Kong.

- The medication review programme led by a clinical pharmacist resulted in a substantial reduction in the use of inappropriate medications among hospitalised elderly patients and all-cause unscheduled readmissions at 1 month after hospital discharge.

- A pharmacist-led medication review programme is an important strategy that can enhance the safety and quality of prescription among elderly patients in hospital.

- It is strongly recommended that these programmes be standardised and implemented in all medical and geriatric wards in Hong Kong.

Introduction

Elderly patients have multiple co-morbidities and

they are consequently prone to multiple medication use. Inappropriate

medication use is common among hospitalised older adults. The number of

drugs taken is one of the important determinants of risk for receiving an

inappropriate medication.1 There is

a high prevalence of unnecessary drug use in frail older people. In one

hospital study, 44% of patients were prescribed at least one unnecessary

drug, with the most common reason being lack of indication.2 The most commonly prescribed unnecessary drug classes

were gastrointestinal, central nervous system, and therapeutic

nutrients/minerals.2 Appropriate

use of drugs is particularly important in the frail older people who are

especially at risk of adverse drug reactions.3

It has been shown that implementation of a clinical pharmacist service has

a positive effect on medication use and health care service utilisation

among hospitalised patients.4 5 A local study in a geriatric hospital demonstrated the

effectiveness of a drug rationalisation programme with involvement of a

clinical pharmacist in reducing the incidence of polypharmacy and

inappropriate medications.6

Interacting with the health care team on patient rounds, interviewing

patients, reconciling medications, and providing patient discharge

counselling and follow-up all resulted in improved outcomes.7 It is for this reason that patient safety strategies

encourage the use of medication reconciliation and clinical pharmacists in

health care systems to reduce adverse drug events.8 9 10

There is not much information about the

effectiveness of a medical review programme among hospitalised elderly

patients in Hong Kong. Two recent local reports that examined the effects

of a clinical pharmacist–led medication review on hospital readmissions

showed conflicting results and did not specifically address elderly

patients.11 12 We therefore conducted a prospective controlled study

to investigate the effectiveness of a comprehensive pharmacist

intervention on medication use and hospital readmission among a group of

geriatric in-patients in Hong Kong.

Methods

This prospective controlled study was conducted in

the geriatric unit of a regional hospital in Hong Kong. The unit has 38

in-patient beds and admits older people aged 65 years or above who are

transferred from an acute hospital after initial stabilisation of medical

and/or geriatric problems. The unit admits more than 1000 patients per

year and provides medical treatment, rehabilitation, and discharge

planning services by a multidisciplinary team composed of a geriatrician,

residents, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and medical

social workers. All patients admitted to the unit during December 2013 to

September 2014 were included. Patients were excluded if they refused to

participate, were terminally ill with a life expectancy of less than 3

months, or if they had already received pharmacist intervention in another

hospital prior to this admission. Eligible subjects were assigned to an

intervention or control group according to the admission day of the week.

Those who were admitted on Monday through Thursday were assigned to the

intervention group, and those admitted on Friday through Sunday to the

control group. This arrangement was to ensure that pharmacist intervention

could be initiated promptly within 48 hours of patient admission.

Demographic data, functional status, co-morbidities, and number of drugs

on admission were collected at admission.

The intervention was conducted by a pharmacist who

was present in the unit from Monday to Saturday. The pharmacist provided

pharmaceutical care from admission to discharge. Interventions performed

by the pharmacist consisted of the following:

(1) Medication reconciliation on admission to

identify unintended discrepancies between medications prescribed on

admission and the usual medications prior to admission—sources to assist

medication reconciliation included: electronic patient record; patient’s

ward case notes; interview with patient and/or patient carer. The number

and type of unidentified discrepancies were recorded.

(2) Medication review to check for medication

appropriateness on admission and also at discharge—medication

appropriateness was assessed by the Medication Appropriateness Index

(MAI).13 There are 10 criteria to

assess for appropriateness, namely indication, effectiveness, dosage,

correct direction, practical direction, drug-drug interaction,

drug-disease interaction, duplication, duration, and expense. For a drug

item coded as ‘inappropriate’, relative weights for each criterion would

apply. A sum of MAI scores could then be calculated to give a score

ranging from 0 to 18. The higher the score, the more inappropriate the

drug. Recommendations from the pharmacist after the reconciliation and

medication review in the intervention group were then communicated to the

in-charge doctor via a written note in the medical records.

Recommendations were reinforced verbally if deemed appropriate by the

pharmacist.

(3) Pharmacist counselling on admission and also at

discharge was provided to improve patients’ drug knowledge to ensure

proper use of drugs and compliance after discharge. A discharge

counselling service was provided for all patients who returned home. The

counselling included any changes to drug regimen; an explanation of each

drug’s indication; any untoward effects that might occur and when to seek

medical advice; and drug storage and administration instructions. To

ensure patient understanding, written information such as patient

information leaflets were given to patients and their carers to remind

them of the correct drug regimen. If the patient was illiterate, a simple

diagram was drawn on drug labels to demonstrate the time of day and number

of tablets to be taken. If necessary, individualised pictorial schedules

with drug images and administration instructions could be produced for

patients and their carers. The assistance of a family member or external

care services such as a community nurse was enlisted if the patient was

found to have compliance issues.

The control group received routine clinical

services. Records of the control group were retrospectively reviewed by

the pharmacist after patient discharge to check for medication

appropriateness on admission and also at discharge. The primary outcome

measure was the appropriateness of prescription as measured by the MAI.

Secondary outcomes included the acceptance rate by physicians, number of

subjects with unintended discrepancies, patient satisfaction with the

programme (for those home-living only), and unplanned hospitalisations 1

and 3 months after discharge.

A sample size of 98 patients per group was required

to have 85% power to detect an effect size of 0.9 on the MAI. Our sample

size was finally set at 210 patients to account for loss of participants

due to dropout or death. This sample size was comparable with a study by

Spinewine et al14 in which MAI was

used as one of the tools to assess appropriateness of prescribing in an

acute geriatric care unit and 203 patients were recruited. Our study

included 212 patients and was expected to have adequate statistical power

to detect differences between groups. Descriptive analyses were performed

and included the number and types of unintended discrepancies, MAI score

upon admission and at discharge, types of drug-related problems, number of

interventions made by pharmacists, and number of recommendations accepted

by doctors and implemented. Outcomes for the two groups before and after

the programme were compared using the t test and Chi squared test.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows version 17.0;

SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], United States) was used and a P value of <0.05

was regarded as statistically significant. The study was approved by the

Cluster Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Authority Hong Kong West

Cluster. Written consent was obtained from the patient or their caregiver.

The absence of pharmacist intervention in the control group was considered

acceptable because a pharmacy service was not a part of routine care at

the institution.

Results

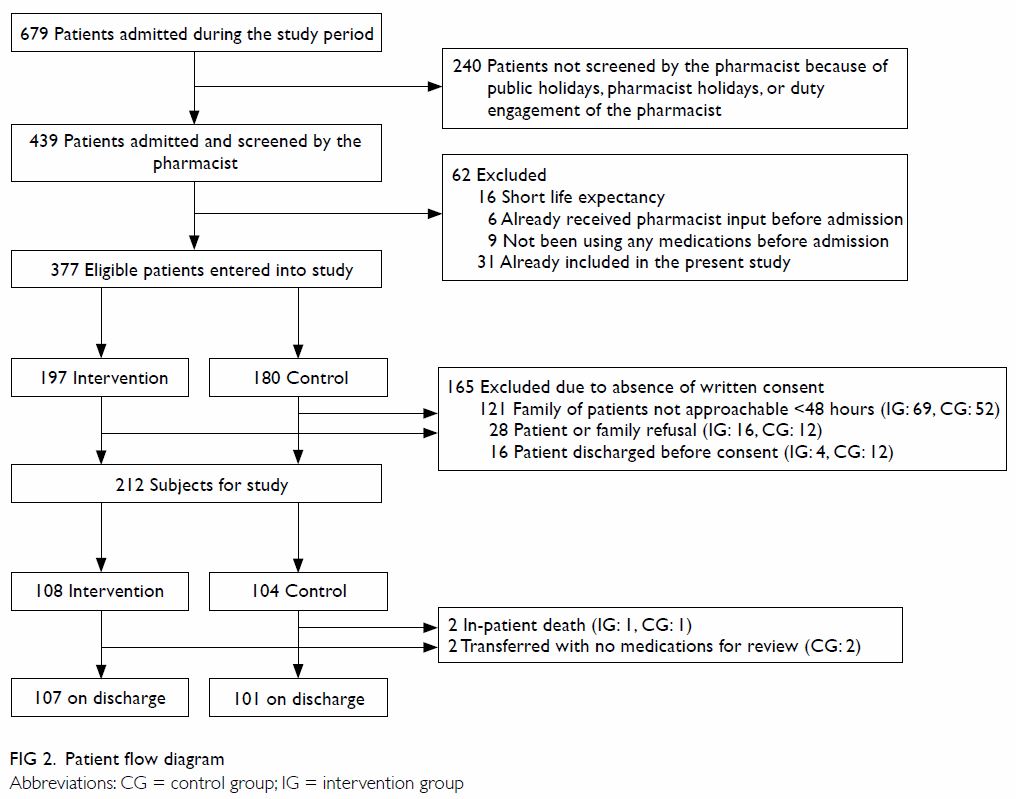

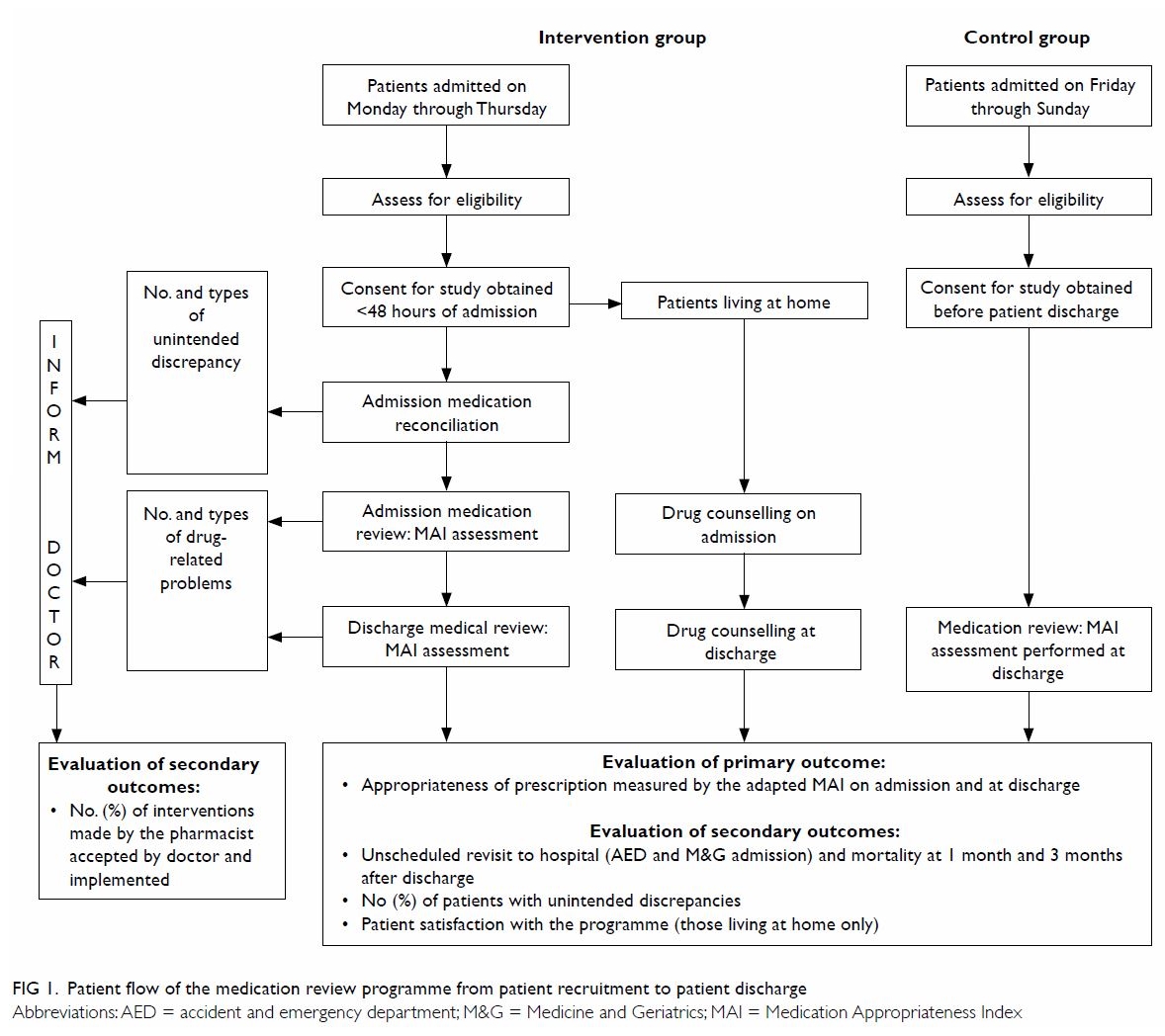

Figure 1 summarises the patient flow from

recruitment to hospital discharge, the components of the medication review

programme, and the planned outcome measures. A total of 212 patients were

recruited. There were 108 subjects in the intervention group and 104 in

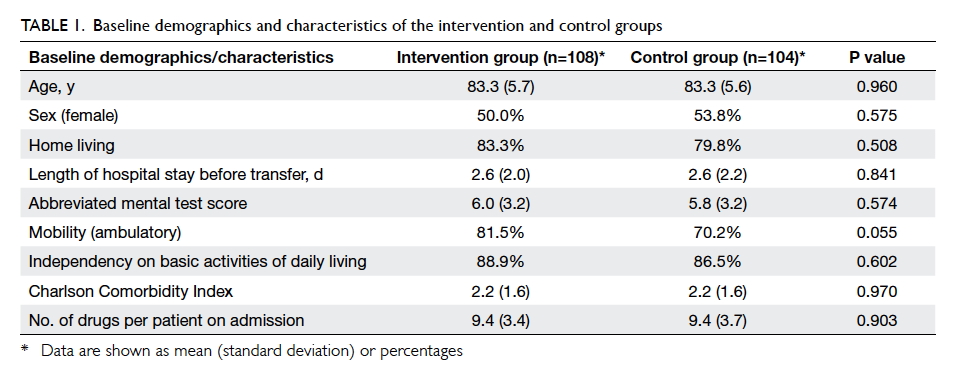

the control group (Fig 2). There were no statistical differences in the

baseline characteristics of patients (Table 1).

Figure 1. Patient flow of the medication review programme from patient recruitment to patient discharge

Appropriateness of prescription

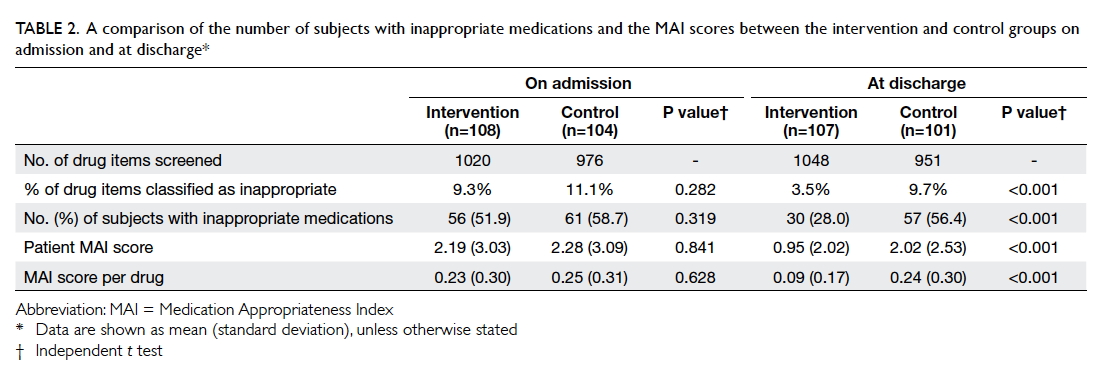

On admission, 51.9% (56/108) of the intervention

group and 58.7% (61/104) of the control group had at least one drug

classified as inappropriate (P=0.319). Overall, 1996 drug items were

reviewed by a pharmacist on admission of which 1020 were from the

intervention group and 976 from the control group. Among them, 9.3% and

11.1% of the drugs, respectively, were classified as inappropriate

(P=0.282). In the intervention group, 93 recommendations were made by the

pharmacist of which 60 (64.5%) were accepted by the physicians and

implemented. The mean (standard deviation) MAI score per patient was

2.19 (3.03) in the intervention group and 2.28 (3.09) in the control group

(P=0.841). The mean MAI score per drug was 0.23 (0.30) in the intervention

group and 0.25 (0.31) in the control group (P=0.628) [Table

2].

After the program and at discharge, the proportion

of subjects with inappropriate medications in the intervention group was

significantly lower than that in the control group (28.0% vs 56.4%;

P<0.001). Among the 1999 drug items reviewed by the pharmacist on

patient discharge, 3.5% (37 of 1048) of the intervention group and 9.7%

(92 of 951) of the control group were classified as inappropriate

(P<0.001). The intervention group also had a significantly lower MAI

score per patient (0.95 (2.02) vs 2.02 (2.53); P<0.001) and MAI score

per drug (0.09 (0.17) vs 0.24 (0.30); P<0.001) implying a significant

reduction in medication inappropriateness after the pharmacist medication

review (Table 2).

Table 2. A comparison of the number of subjects with inappropriate medications and the MAI scores between the intervention and control groups on admission and at discharge

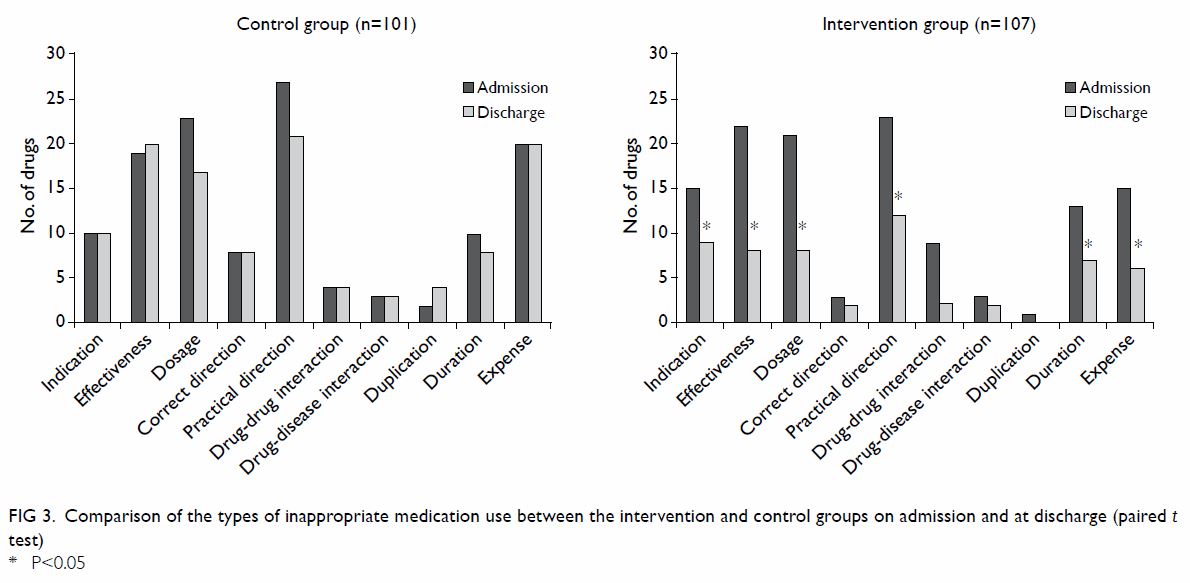

Types of inappropriateness according to the MAI in

the two groups are illustrated in Figure 3. In both the intervention and control

groups, the common causes were indication, effectiveness, dosage,

practical direction, duration, and expense. After the programme, there was

a significant reduction in the number of these drug-related problems in

the intervention group.

Figure 3. Comparison of the types of inappropriate medication use between the intervention and control groups on admission and at discharge (paired t test)

Unintended discrepancy of medications

Among the 108 subjects in the intervention group,

19.4% had at least one unintended discrepancy in medications, involving a

total of 43 drug factors. The majority (90.7%) of these factors were

omission of drugs, and 4.6% were due to inappropriate dosages. Of all the

drug factors involved, 69.8% involved prescribed drugs from hospitals,

25.6% were from a private clinic, and 4.6% were over-the-counter drugs.

Overall, 41 recommendations were made, of which 32 (78.0%) were accepted

by physicians and implemented.

Patient satisfaction

Contact was made with 50 of the 90

non-institutionalised subjects 1 month after discharge to assess

satisfaction with the programme. Of those contacted, 98.0% were satisfied

with the programme and only one (2.0%) patient expressed a neutral

opinion.

Impact on health care services utilisation and

mortality

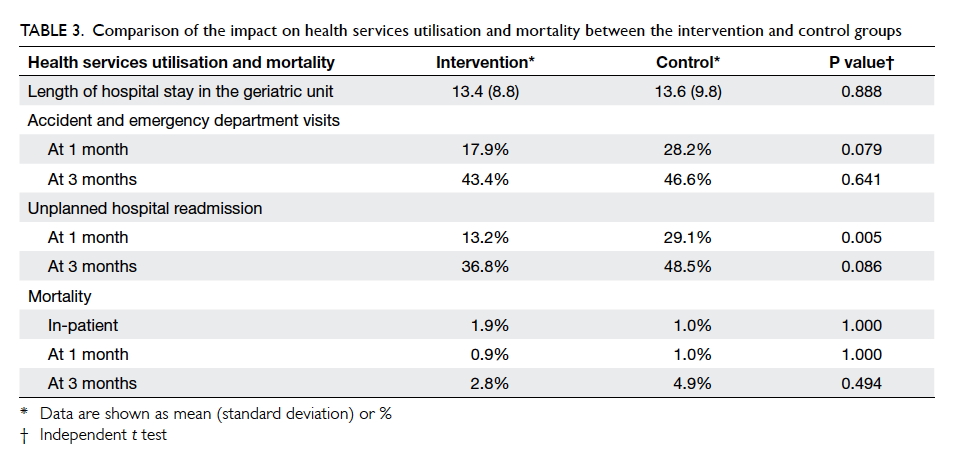

There were no statistical differences in the length

of hospital stay, in-patient mortality, or mortality at 1 month or 3

months after discharge. There was also no statistical difference in the

number of attendances at the accident and emergency department 1 month or

3 months after discharge or in the unplanned hospital readmission rate at

3 months after discharge. The unplanned hospital readmission rate 1 month

after discharge, however, was significantly lower in the intervention

group than that in the control group (13.2% vs 29.1%; P=0.005) [Table

3].

Table 3. Comparison of the impact on health services utilisation and mortality between the intervention and control groups

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

local prospective controlled study to investigate the effectiveness of a

pharmacist-led medication review programme on medication appropriateness

and clinical outcomes among geriatric in-patients in Hong Kong. This study

has demonstrated superior outcomes that favour a pharmacist-led

intervention. There was a substantial reduction in the use of

inappropriate medications and all-cause unscheduled readmissions 1 month

after hospital discharge. Nonetheless, analysis of length of hospital

stay, number of all-cause emergency department visits, and mortality rate

favoured neither the intervention nor the usual pharmacist care.

This study showed that one in five geriatric

in-patients had an unintended medication discrepancy on admission. This

figure was slightly higher than that found in a group of 3317 hospitalised

medical patients (13%) over 1 year in an acute hospital in Hong Kong by

Kwok et al.15 Subjects in our

study were all elderly patients, whereas those in Kwok et al’s study were

adults of all ages. Elderly subjects tend to have polypharmacy and thus

are more vulnerable to unintended medication discrepancy when they move in

and out of hospital or are transferred to another health care unit for

further care. Unjustifiable medication discrepancies account for more than

half of the medication errors that occur during transition of care and up

to one third have the potential to cause harm.16

17 This does not bode well for our

elderly patients with multiple co-morbidities.

Up to 30% of the discrepancies in our study

involved medications that had been prescribed by private practitioners or

purchased over-the-counter. Unlike medications prescribed from the

Hospital Authority, these medications might be overlooked unless the

admitting doctor specifically asks for a detailed drug history from the

patient. Knowing the medication history and hence resuming these

medications are important if new health problems are to be prevented.

Pharmacist-led medication reconciliation is therefore a critical process

that can enhance patient medication safety by compiling a complete and

accurate medication list for patients in hospital.

This study revealed that more than half of the

subjects (55.2%) received inappropriate medications. The majority of

reasons for inappropriateness related to effectiveness, dosage, practical

directions, and expense as reflected by the MAI. The inappropriate dosage

and the questionable effectiveness might lead to not only failed

pharmacological effects, but also potentially an untoward adverse drug

reaction, especially in elderly individuals with pre-existing organ

dysfunction.18 When a medication

is not used according to the practical directions, it may lead to patient

non-compliance. Optimising outcomes while reducing costs are the keys for

medication management in today’s health care environment.19 Often there are several choices of drugs available to

treat a disease or health condition and some are more expensive than

others. The involvement of a ward-based pharmacist to review medication

can enhance the use of appropriate medications in hospitalised patients

and potentially reduce medication costs.

Following the medication review (60/93) and

medication reconciliation (32/41), there were 92 recommendations that were

accepted by the physician. The overall acceptance rate by physicians and

the implementation of pharmacist recommendations in our study was 68.7%

(92/134). This figure ranged from 39% to 100% in a previous systematic

review of 32 studies.4 Our study

did not specifically record recommendations accepted by physicians but not

implemented. Hence the acceptance rate in our study may be underestimated.

Nevertheless, the clinical pharmacist is encouraged to discuss the

medication-related problems in person with the physician as well as

contacting the patient in order to enhance the implementation rate.4

Pharmacy departments within the public hospital

system in Hong Kong have strived to implement the aforementioned patient

safety strategies in different specialties. Nonetheless, this is not a

standard practice simply because of insufficient pharmacist staffing

resources. In some hospitals, a pharmacist service is provided in wards,

but this does not apply in all cases and is not standardised. Experience

of a pharmacist-led medication reconciliation service from an acute

teaching hospital in Hong Kong showed promising results over a 1-year

trial run with high acceptance and recognition by other health care

professionals.16 It is hoped that

the clinical role of clinical pharmacists in patient medication management

in hospitals can be encouraged. Another local study has demonstrated a

positive impact on medication safety in patients with diabetes by

pharmacists’ intervention in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team.20 The feasibility of incorporating

a pharmacist as part of a multidisciplinary team of health care

professionals must be explored in geriatric wards in Hong Kong. With

increasing life expectancy, the expanding elderly population will equate

to an increase in morbidity and mortality owing to drug-related problems

where the need for trained health care professionals to perform medication

reviews will be in even greater demand. To enhance safe drug use with

limited resources, a systematic approach must be adopted to cover all

aspects that affect drug therapy.

In terms of the impact on health care services

utilisation, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of the

effectiveness of a pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programme

revealed a substantial reduction in the rate of all-cause readmissions

(19%), all-cause emergency department visits (28%), and adverse drug

event–related hospital visits (67%).21

Our study revealed a significant reduction in unplanned hospital

admissions (all-cause admission) at 1 month but not at 3 months. This

implication might be due to an inadequate sample size to show the

difference at 3 months. Alternatively, it might also imply that pharmacist

intervention needs to be continued after patient discharge in order to

have a sustained effect. This is supported by a study by Schnipper et al22 in which pharmacist intervention

after patient discharge was associated with a lower rate of preventable

adverse drug events 30 days after hospital discharge.

During the pharmacist review, cost-effectiveness of

drug use was assessed through MAI. Alternative options such as

less-expensive formulations or drugs but of the same quality would be

recommended to the doctor in-charge. This was a means of encouraging

cost-effective use of drugs in a hospital. Furthermore, the reduction in

unscheduled hospital readmissions in the intervention group implies a

potential saving in hospital costs. Although a detailed analysis was not

performed in this study, a rough estimation is that nearly HK$2 million

may be saved annually as a result of lower drug costs and reduced hospital

admissions, even after considering the cost of employing a pharmacist. The

estimation was based on the following calculations. The estimated drug

saving as a result of a switch to a more cost-effective alternative was

HK$7500 among the 108 patients in the intervention group. This can be

projected to a saving of about HK$69 500 in a unit that admits 1000

patients annually. In the current study, there were 16 fewer readmissions

in the intervention group compared with the control group. Assuming a

daily cost of an acute hospital bed is HK$4680 and the mean length of

hospital stay is 3 days, this equates to a potential saving of about HK$2

080 000 per year in a unit that admits 1000 patients annually. If it is

assumed that a pharmacist spends 30 minutes for each patient at an hourly

salary of HK$433, the projected cost of an additional pharmacist to run

the intervention would be HK$216 500 per year. The net annual saving of

this programme to serve 1000 patients in this unit would thus still be

close to HK$2 million.

This study had several limitations. First, a

substantial proportion (35%) of all the admitted patients were not

screened by a pharmacist on admission. This was due to a temporary pause

in subject recruitment when patients were admitted on public holidays,

when the pharmacist was on holiday or when she had to relieve another

pharmacist in the hospital. Moreover, a substantial proportion (44%) of

eligible subjects were not included owing to no consent or refusal. These

factors might have resulted in selection or self-selection bias. Second,

subject recruitment was not randomised, but done according to the day of

admission. This might be a source of bias. Nevertheless, this would have

minimal influence on the outcomes, as the baseline characteristics of the

intervention and control groups were comparable. Third, the pharmacist who

carried out the review and data extraction was not blinded to the study

hypothesis and the group status of the subjects. This could potentially

lead to information bias, although this might be partially offset by the

fact that the majority of the information or data on the outcome measures

were taken with reference to a well-established and validated tool.

Fourth, this study was performed in a single unit, so generalisation to

other settings is not possible. Fifth, MAI is an implicit tool that is

subjective. A single pharmacist as the rater might limit the reliability

of the assessment results. Nevertheless, the more explicit tools of

STOPP/START criteria23 had also

been referred to in addition to the MAI during the review process. Sixth,

this study only addressed appropriateness of drug use, whereas underuse of

drugs was not investigated. Finally, this study could not conclude a

causal relationship between the reduction in inappropriate medications and

the reduction in unscheduled hospital readmissions because there were

several components in the intervention that included a medication review,

medication reconciliation, and discharge counselling. It is difficult to

be certain which of these components alone or in combination gave rise to

the positive outcome of this study.

On the other hand, there were several strengths in

this study. This was the first prospective controlled study of the effect

of a pharmacist-led medication review programme on medication use and

health services utilisation involving over 200 Chinese elderly patients in

Hong Kong. Second, a well-validated tool was used to assess medication

appropriateness. The use of the MAI tool focused on the patient and the

entire medication regimen. Third, there was a comprehensive review of

outcomes including quality of prescribing, health services utilisation,

mortality, length of hospital stay, and patient satisfaction.

Conclusions

This study supported the role of a hospital-based

clinical pharmacist to enhance appropriate medication use among elderly

Chinese in-patients. A systematic medication review programme in a

geriatric unit resulted in a reduced number of drug omissions and fewer

inappropriate medications. The service provided by the clinical pharmacist

and supported by geriatricians was welcomed by patients and their carers.

Together with the potential to reduce hospital readmissions and their

associated cost, it is hoped that an in-hospital pharmacist-led medication

review programme can be recognised as one of the important strategies to

enhance the safety and quality of prescription among elderly patients in

hospitals. It is strongly recommended that these programmes be

standardised and implemented in all medical and geriatric wards in Hong

Kong. Future studies should recruit a larger sample size in a randomised

controlled design in other geriatric hospital settings to reiterate our

findings. Furthermore, these studies might consider including adverse drug

event–related hospital visits as one of the outcome measures.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

References

1. Onder G, Landi F, Cesari M, Gambassi G,

Carbonin P, Bernabei R; Investigators of the GIFA Study. Inappropriate

medication use among hospitalized older adults in Italy: results from the

Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly. Eur J Clin Pharmacol

2003;59:157-62. Crossref

2. Hajjar ER, Hanlon JT, Sloane RJ, et al.

Unnecessary drug use in frail older people at hospital discharge. J Am

Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1518-23. Crossref

3. Routledge PA, O’Mahony MS, Woodhouse KW.

Adverse drug reactions in elderly patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol

2004;57:121-6. Crossref

4. Graabaek T, Kjeldsen LJ. Medication

reviews by clinical pharmacists at hospitals lead to improved patient

outcomes: a systematic review. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol

2013;112:359-73. Crossref

5. Gillespie U, Alassaad A, Henrohn D, et

al. A comprehensive pharmacist intervention to reduce morbidity in

patients 80 years or older: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med

2009;169:894-900. Crossref

6. Chan FH, Pei CK, Chiu KC, Tsang EK.

Strategies against polypharmacy and inappropriate medication—are they

effective? Australas J Ageing 2001;20:85-9. Crossref

7. Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ,

Schnipper JL. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a

systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:955-64. Crossref

8. The ACHS EQuIP5 (5th edition of the ACHS

Evaluation and Quality Improvement Program) clinical standard 1.5,

criterion 1.5.1.: Medication are managed to ensure safe and effective

consumer/patient outcomes. Sydney: The Australian Council on Health Care

Standards; 2010.

9. Medication reconciliation. Patient

Safety Network. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. US Department

of Health & Human Services. Available from:

http://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer.aspx?primerID=1. Accessed 11 Jun 2017.

10. Gurwitz J, Monane M, Monane S, Avorn

J. Polypharmacy. In: Morris JN, Lipsitz LA, Murphy K, Bellville-Taylor P,

editors. Quality care in the nursing home. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book;

1997: 13-25.

11. Wong CY, Lee TO, Lam MP. Pharmacist

discharge intervention programme to reduce unplanned hospital use in

patients with polypharmacy. Hong Kong Pharm J 2017;24(Suppl 1):S18.

12. Chan HH. To reduce avoidable

readmission of patients who are categorized as high risk by 30-day

hospital readmission model at medical ward of United Christian Hospital

through medication reconciliation and discharge counseling. Hong Kong

Pharm J 2017;24(Suppl 1):S21.

13. Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, et

al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol

1992;45:1045-51. Crossref

14. Spinewine A, Swine C, Dhillon S, et

al. Effect of a collaborative approach on the quality of prescribing for

geriatric inpatients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc

2007;55:658-65. Crossref

15. Kwok CC, Mak WM, Chui CM.

Implementational experience of medical reconciliation in Queen Mary

Hospital. Hong Kong Pharm J 2009;16:50-2.

16. Rozich JD, Howard RJ, Justeson JM,

Macken PD, Lindsay ME, Resar RK. Standardization as a mechanism to improve

safety in health care. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2004;30:5-14. Crossref

17. Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R,

et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital

admission. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:424-9. Crossref

18. Cameron KA. Caregivers’ guide to

medications and aging. National Center on Caregiving, Family Caregiver

Alliance 2004. Available from:

https://www.caregiver.org/caregiver%CA%BCs-guide-medications-and-aging.

Accessed 11 Jun 2017.

19. Splawski J, Minger H. Value of the

pharmacist in the medication reconciliation process. P T 2016;41:176-8.

20. Chung AY, Anand S, Wong IC, et al.

Improving medication safety and diabetes management in Hong Kong: a

multidisciplinary approach. Hong Kong Med J 2017;23:158-67. Crossref

21. Mekonnen AB, McLachlan AJ, Brien JA.

Effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on

clinical outcomes at hospital transitions: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010003. Crossref

22. Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC,

et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events

after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:565-71. Crossref

23. Lam MP, Cheung BM. The use of

STOPP/START criteria as a screening tool for assessing the appropriateness

of medications in the elderly population. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol

2012;5:187-97. Crossref