Hong Kong Med J 2018 Apr;24(2):128–36 | Epub 4 Apr 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176960

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Effect of a financial incentive on the acceptance of a

smoking cessation programme with service charge: a cluster-controlled

trial

KS Wong, MB, BS1; SN Fu, MB, BS, MFM2;

KL Cheung, MB, ChB2; MC Dao, MB, BS2; WM Sy, MB, BS2

1 Family Medicine and General

Out-patient Clinics, Kowloon Central Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong

Kong

2 Family Medicine & Primary Health

Care, Kowloon West Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KS Wong (wks638@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Frontline health

care professionals in Hong Kong may encounter high refusal rates for the

Hospital Authority’s Smoking Counselling and Cessation Programme (SCCP)

when smokers know it is subject to a service charge. We compared SCCP

booking and attendance rates among smokers with or without a financial

incentive.

Methods: In this multicentre

non-randomised cluster-controlled trial, adult smokers who attended one

of six general out-patient clinics between November 2015 and April 2016

were invited to join an SCCP. Attendees in the three intervention-group

centres but not the three control-group centres received a supermarket

coupon to offset the service charge.

Results: A total of 173 smokers

aged 18 years or older (92 in the intervention group and 81 in the

control group) were recruited into the study. In the intervention group,

47 smokers (51%) agreed via a questionnaire that they would join the

SCCP, compared with only 23 smokers in the control group (28%). The

booking rates were 83% (n=39) in the intervention group and 83% (n=19)

in the control group. Among those who had booked a place, 19 (49%)

intervention-group participants and 11 (58%) control-group participants

attended an SCCP session. Multivariable logistic regression revealed

that offering a coupon was associated with agreeing to join an SCCP

(odds ratio=4.963, 95% confidence interval=2.173-11.334; P<0.001) and

booking an SCCP place (odds ratio=4.244, 95% confidence

interval=1.838-9.799; P<0.001).

Conclusion: Provision of a

financial incentive was positively associated with agreement to join an

SCCP and booking an SCCP place. Budget holders should consider providing

the SCCP free of charge to increase smokers’ access to the

service.

New knowledge added by this study

- This study reveals that provision of a financial incentive to offset the service charge of the Smoking Counselling and Cessation Programme in Hong Kong might increase the proportion of smokers who agree to join the programme and make an appointment.

- Budget holders should consider providing a free Smoking Counselling and Cessation Programme to increase smokers’ access to the service.

Introduction

There is no doubt that smoking is a serious hazard

to health.1 2 3 One in two

smokers will be killed by smoking; if one can help two smokers to quit, at

least one life will be saved.4

Individual counselling by trained therapists can assist smokers to quit.5 6

7 The counselling usually involves

review of the participant’s smoking history and motivation to quit,

provision of problem-solving strategies to deal with high-risk situations,

and encouragement. Smokers who receive individual counselling are 39% more

likely to cease smoking in the long term than smokers who receive minimal

behavioural intervention.5 Another

method to increase the smoking cessation rate is nicotine replacement

therapy (NRT). Such therapy (eg, gum, transdermal patch, and lozenges) is

cost-effective in smoking cessation and increases the rate of quitting by

50% to 70%.8 9 10 11 Combining counselling and pharmacotherapy has been

shown to further increase smoking cessation success rates by more than 80%

when compared with minimal intervention or usual care.12 If a smoker quits smoking in the absence of external

assistance, there is only a 3% to 5% chance of sustained abstinence at 6

to 12 months.13

In Hong Kong, the Smoking Counselling and Cessation

Programme (SCCP) consists of individual counselling and provision of NRT

and is available from the Hospital Authority; similar services are also

provided by the Department of Health and the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals.14 The Hospital Authority operates

58 smoking cessation and counselling centres. Despite this available

support, only about 19% of current smokers in Hong Kong have tried a

smoking cessation service.15 In

contrast, the prevalence of assisted quit attempts was 59.4% in Australia

in 2008-2009 and 53.6% in the United Kingdom in 2010.16

The SCCP in Hong Kong is offered as part of chronic

care, and general out-patient clinics (GOPCs) provide a good opportunity

for health care professionals to refer smokers to an SCCP. Frontline GOPC

health care professionals in Hong Kong may encounter high refusal rates of

SCCP service when smokers know they must pay a service charge. Currently,

smoking cessation and counselling centres SCCC charge HK$50 [~US$6.40]

(HK$45 [~US$5.80] at the time of this study) for an initial face-to-face

consultation, unless the client is exempt (eg, those receiving the

Comprehensive Social Security Allowance or civil servants). There is no

extra charge for NRT.

A review article in the Cochrane Library by Reda et

al17 proposed that if all costs to smokers are covered, the proportion of

smokers who attempt to quit, use smoking cessation treatments, and succeed

in quitting will significantly increase compared with provision of no

financial support. Reda et al17

also suggested that even though the absolute differences in quitting were

small when an intervention group was compared with a control group (total

events: 134 of 1409 vs 75 of 1351, respectively), the costs per person

successfully quitting were low or moderate (US$119 to US$6450). However,

all the studies included in that review were conducted in western

countries, where the health care financing systems may differ from that of

Hong Kong. In this study, we aimed to determine whether the booking and

attendance rates at a smoking cessation service (SCCP) in a primary care

setting could be increased if the patient received a financial incentive,

as payment-in-kind, to offset the service fee.

Methods

Study design and population

This was a multicentre non-randomised

cluster-controlled trial involving six GOPCs of the Hong Kong Hospital

Authority’s Kowloon West Cluster and conducted from November 2015 to April

2016. The study protocol was approved by the Hospital Authority Kowloon

West Cluster Research Ethics Committee (Ref No. KW/EX-15-169(91-08)).

Non-random cluster sampling was used to choose participating clinics and

assign them to study group, in order to avoid contamination of

participants between the intervention and control groups. Three clinics

(Ha Kwai Chung GOPC, West Kowloon GOPC, and Tsing Yi Cheung Hong GOPC)

were assigned to the intervention group and three (Cheung Sha Wan GOPC, Li

Po Chun GOPC, and South Kwai Chung GOPC) to the control group. A standard

regular SCCP was available at all six clinics. The SCCP counsellors were

trained nurses or pharmacists and all underwent the same smoking cessation

counselling training provided by the Hospital Authority Head Office. The

GOPC staff and SCCP counsellors were not involved in clinic selection or

assignment.

The study centres were six of the 73

government-funded primary care GOPCs, and the majority of their patients

were from a lower socio-economic class or older patients with chronic

illnesses. The patient profiles from the six GOPCs shared a similar

socio-demographic background and disease profile. There was no pre-study

SCCP booking rate available, but the total number of smokers recruited

from the three control clinics into the SCCP during the study period was

similar to the number of SCCP referrals made by the three clinics during

an equivalent period in the previous year (November 2014 to April 2015).

The attendance rate for booked SCCP appointments was logged by the clinic

computer system and was 50% to 60% among all six clinics.

Convenience sampling was used to recruit current

smokers at the time of recruitment,15

who were identified during a doctor’s consultation or nurse’s assessment

during the daytime. Information about this study and possible recruitment

of patients for SCCP referral was given to doctors and nurses before the

start of the study. After valid consent had been obtained, participants

were invited to complete a questionnaire to provide background

information, smoking status, and decision to join an SCCP. Assistance was

given with the questionnaire if required. The questionnaires distributed

to the control group (online supplementary Appendix 1) and the intervention group (online

supplementary Appendix 2) stated the usual SCCP service charge of

HK$45. The intervention group’s questionnaire additionally stated that a

HK$50 supermarket coupon would be given to SCCP attendees. Those who

agreed to participate in the SCCP were directed to make an appointment via

the registration counter.

The SCCP counsellors in the intervention group were

briefed by the authors about the process of issuing a supermarket coupon

as payment in-kind to SCCP attendees. The SCCP session was carried out as

usual, regardless of study group. In clinics in the intervention group,

the supermarket coupon was given to SCCP participants after payment of the

service charge.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Current smokers who were aged 18 years or older

were eligible for the study. Participants were excluded if (1) the SCCP

service charge was waived—for example, if they were a Comprehensive Social

Security Allowance recipient or a civil servant; (2) they were as mentally

incapacitated and unable to give consent; or (3) they were pregnant, as

there was concern that NRT may increase the risk of congenital respiratory

anomalies.18

Recruitment questionnaire

A structured questionnaire in traditional Chinese

script (online supplementary Appendices 1 and 2) was used to collect the

following information:

(1) Age, sex, mean personal monthly income, and

whether the participant thought the clinic was a convenient place to go;

(2) Smoking history: age when starting smoking,

number of years of smoking, the mean number of cigarettes consumed per day

(CPD), and time to the first cigarette of the day (TTFC) after waking. The

nicotine dependence level was measured by CPD and TTFC, which have been

shown to be independent predictors of quitting outcome.19 A categorical scoring method has been deemed adequate

for many purposes19 and was

adopted in this study (CPD categories of 0-10, 11-20, 21-30, and ≥31; TTFC

categories of ≤5, 6-30, 31-60, and ≥61 minutes);

(3) Rating (range, 0-10) of perceived importance

of, readiness for, and confidence in smoking cessation, which have been

reported to be associated with smoking behavioural change20;

(4) If the smoker agrees to join the SCCP.

The questionnaire comprised 14 questions. The

relevance and content validity of the questionnaire were reviewed by

senior doctors. It was also pilot-tested in 10 smokers for face validity.

Outcome measures

The rates of agreement between questionnaire

response rate for intention to book an SCCP appointment, actual SCCP

booking rate via the registration counter, and SCCP attendance rate were

compared between the intervention and control groups. Defaulters or

participants who rescheduled their SCCP sessions outside the study period

were treated as non-attendees. Smokers who joined the SCCP were followed

up by telephone by smoking-cessation counsellors on the seventh day after

the first consultation to enquire whether they had quit smoking and were

not smoking on the day of the call. This is a standard outcome measure of

the SCCP used by the Hospital Authority.

Sample-size calculation

The sample size was based on the annual quit rate

of smokers in 2014 (of 9.6%) for all GOPCs under the Hospital Authority,

according to an internal report. In a Cochrane review of health care

financing systems to increase the uptake of tobacco-dependence treatment,

full financial interventions (ie, covering all costs) directed at smokers

could increase abstinence rate at 6 months or longer by 2.45 times that of

smokers with no financial intervention (risk ratio=2.45, 95% confidence

interval [CI]=1.17-5.12, I2=59%, 4 studies).17 In a study by Kaper et al,21

the adjusted odds ratio for abstinence after reimbursement was 2 to 4

times that after no reimbursement. It was thus estimated that offering

reimbursement to attend an SCCP would triple the programme attendance

rate. Using the formula established by Casagrande et al,22 65 participants were required in each group in order

to obtain an alpha of 0.05 and 80% power. Assuming a 20% attrition rate,

80 participants were required in each group.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed with SPSS (Windows

version 20.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States). The level of

significance was set at 5%. Data of the intervention and the control

groups were summarised by descriptive statistics. Categorical variables

were expressed as percentages and compared between the two groups by

Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables

were tested for normality with Shapiro-Wilk’s test. Normally distributed

variables were expressed as means with standard deviations and compared

with Student’s t test. Variables that were non-normally

distributed were presented as medians with interquartile ranges and

compared with the Mann-Whitney U test. The association between

participants’ characteristics, reimbursement, and outcomes were studied by

univariate logistic regression analysis and multivariable logistic

regression analysis using backward elimination, yielding crude odds ratios

(ORs) and 95% CIs. Intention-to-treat analysis was used, and missing data

were handled by listwise deletion.

Results

Participant recruitment

In the control group clinics, a total of 90 smokers

were approached, of whom two refused to participate in the study (response

rate, 98%). Seven were excluded, as their questionnaires were incomplete

or their SCCP fee would have been waived. In the intervention group

clinics, a total of 151 smokers were approached, of whom 28 refused to

participate in the study (response rate, 81%). Thirty-one were excluded,

as their questionnaires were incomplete or their SCCP fee would have been

waived. There were 81 and 92 smokers (total, 173) recruited into the

control group and intervention group, respectively.

Study population characteristics

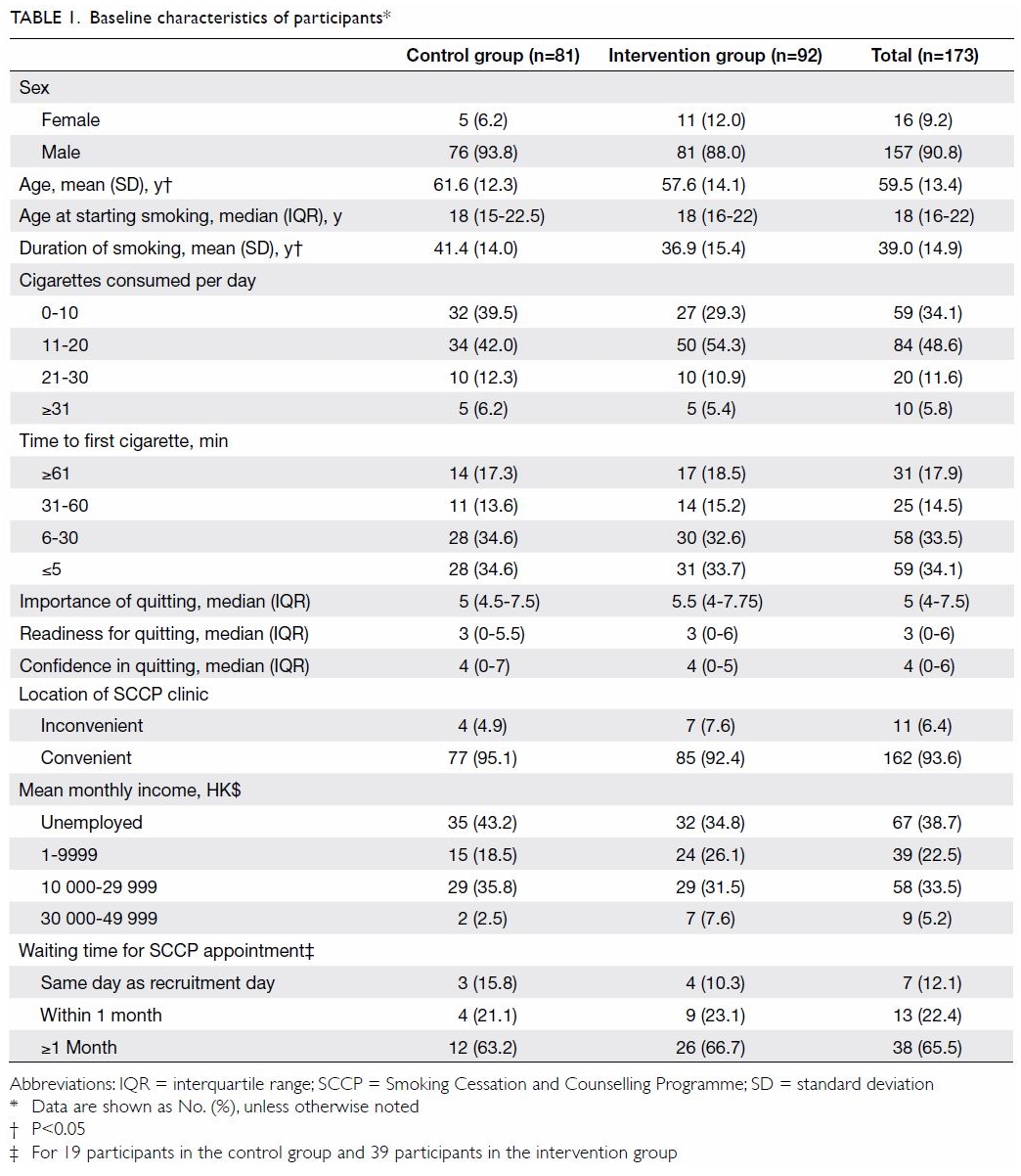

There was no statistical difference between the two

groups in terms of sex; age when starting smoking; mean cigarette

consumption per day; TTFC; perceived importance of, readiness for, and

confidence in smoking cessation; perceived convenience of clinic location;

mean monthly income; and waiting time for SCCP (Table 1). More than 90% of participants were male,

had a mean monthly income of <HK$30 000, and believed that the SCCP

clinic was conveniently located. The median age at starting smoking was 18

years. Nearly half of the smokers were medium smokers, consuming 11 to 20

CPD. The TTFC was less than 31 minutes for more than 67% of smokers. The

rating (from 0 to 10) of perceived importance of, readiness for, and

confidence in quitting was 5, 3, and 4, respectively. The waiting time for

an SCCP appointment was longer than 1 month for over 65% of participants.

The age and the duration of smoking of the

participants were statistically different between the two groups. The mean

age of the control group was 4 years older than that of the intervention

group (61.6 vs 57.6 years; P=0.048). The mean duration of smoking in the

control group was 4 years longer than that in the intervention group (41.4

vs 36.9 years; P=0.047).

Outcomes

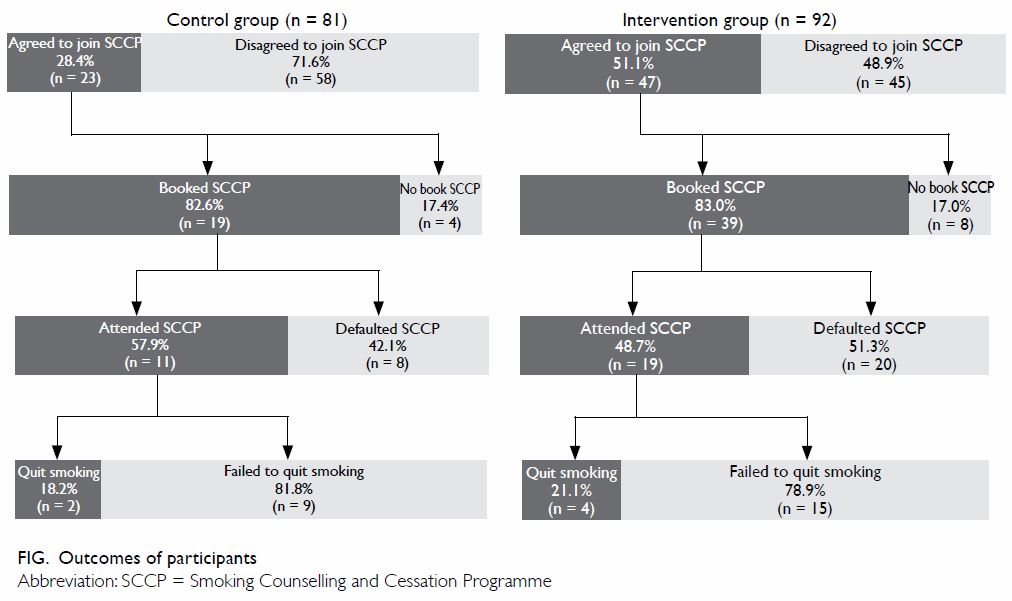

The Figure summarises the SCCP booking and attendance

rates. In the intervention group, 47 smokers (51%) indicated on the

questionnaire their agreement to join an SCCP, whereas only 23 smokers

(28%) did so in the control group. Of those who agreed in principle, 39

(83%) in the intervention group made a booking compared with only 19 (83%)

in the control group. For those who had booked an SCCP place, 19 (49%) and

11 (58%) attended the sessions in the intervention and control group,

respectively. Three smokers (16%) in the intervention group were lost to

follow-up and were counted as non-quitters. Four smokers (21%) in the

intervention group and two (18%) in the control group quit successfully by

the seventh day.

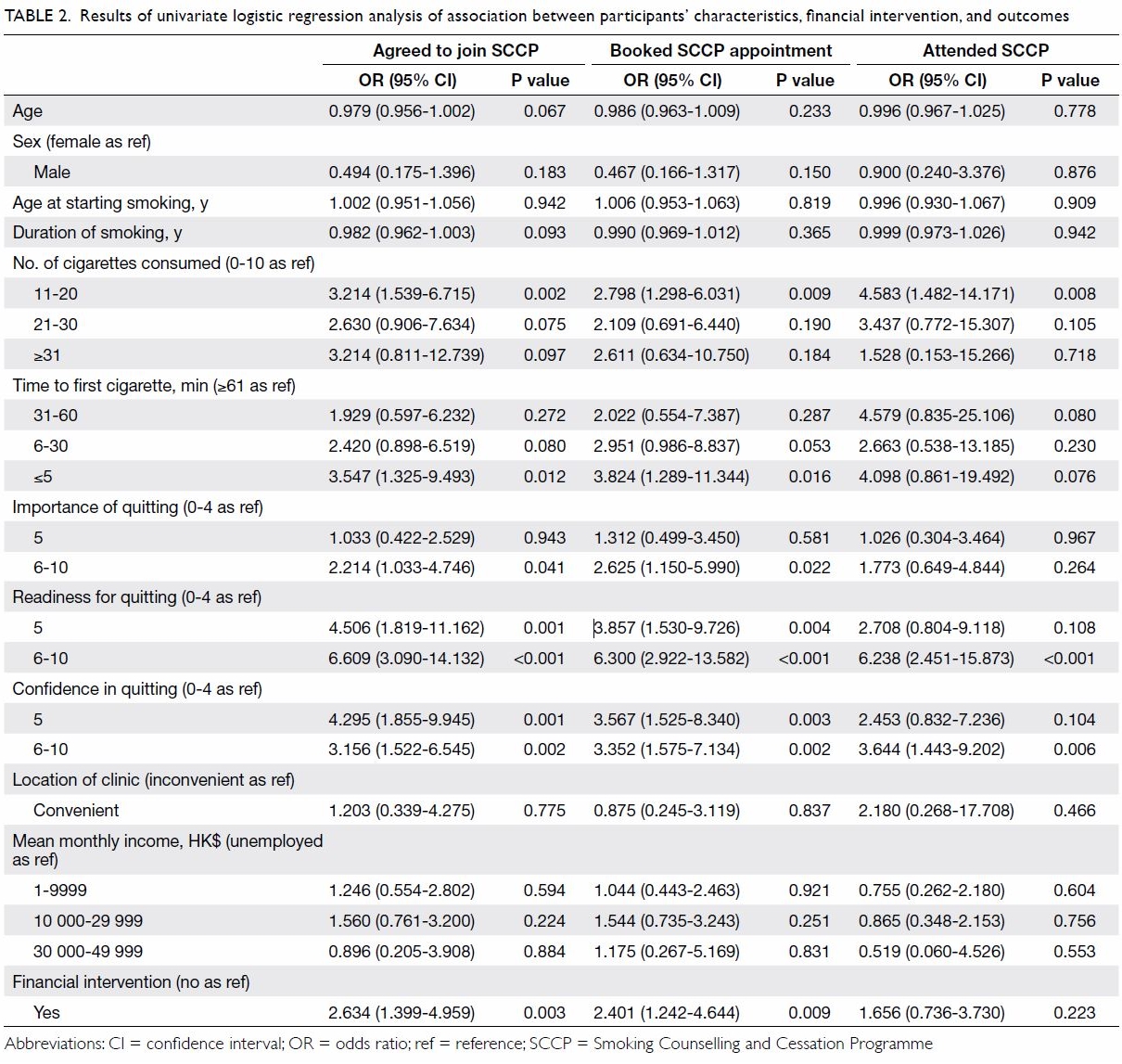

Univariate logistic regression analysis (Table

2) revealed that the financial intervention was associated with a

higher rate of agreeing to join an SCCP (OR=2.634, 95% CI=1.399-4.959;

P=0.003) and booking of an SCCP appointment (OR=2.401, 95% CI=1.242-4.644;

P=0.009), but not with attending an SCCP. Factors that were associated

with a higher rate of agreeing to join, booking, and attending an SCCP

session were consuming 11 to 20 CPD and higher ratings of perceived

readiness for and confidence in smoking cessation. Other factors that were

associated with a higher rate of agreeing to join and booking an SCCP

session were ≤5 minutes for TTFC and higher rating of perceived importance

of smoking cessation.

Table 2. Results of univariate logistic regression analysis of association between participants’ characteristics, financial intervention, and outcomes

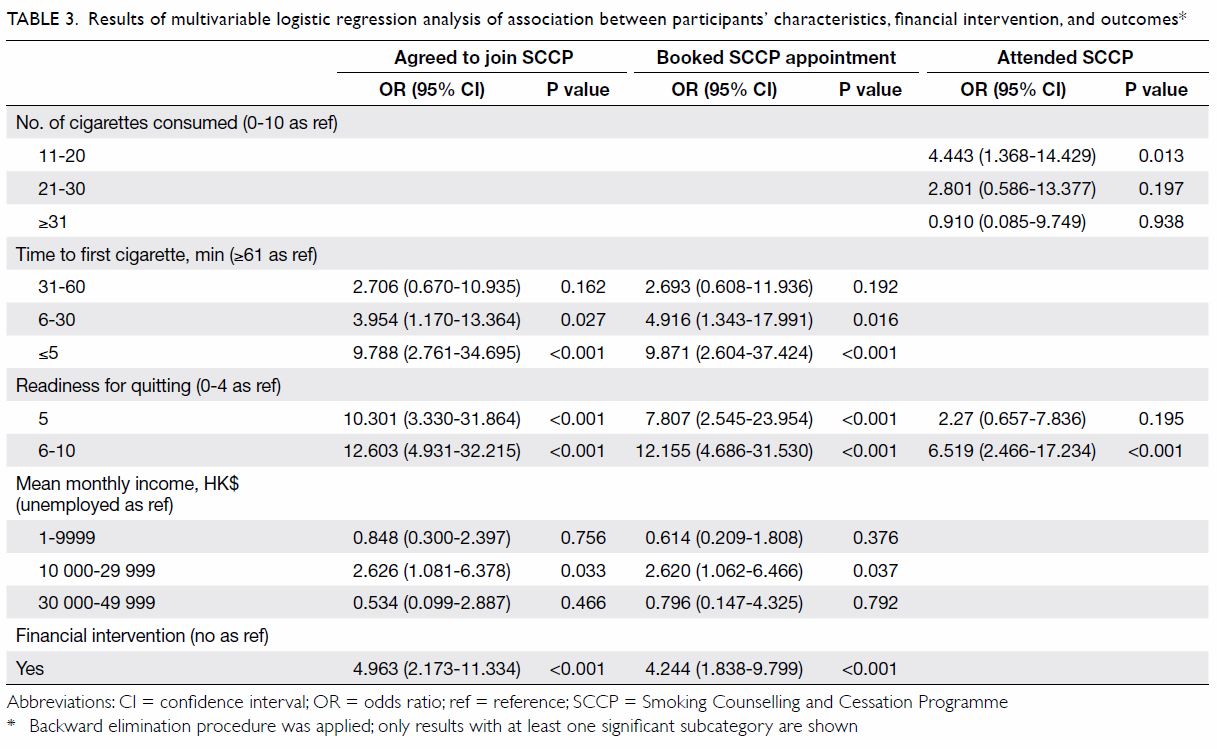

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table

3) revealed that the financial intervention was associated with a

higher rate of agreeing to join an SCCP (OR=4.963, 95% CI=2.173-11.334;

P<0.001) and of booking an SCCP appointment (OR=4.244, 95%

CI=1.838-9.799; P<0.001), but not with actual attendance. Higher

ratings of smokers’ perceived readiness for smoking cessation was

associated with a higher rate of agreeing to join, booking, and attending

an SCCP session. Other factors that were associated with a higher rate of

agreeing to join an SCCP and making a booking were ≤5 minutes and 6-30

minutes of TTFC and a mean monthly income of HK$10 000-29 999. Mean

cigarette consumption of 11 to 20 CPD was associated with a higher rate of

attendance at an SCCP.

Table 3. Results of multivariable logistic regression analysis of association between participants’ characteristics, financial intervention, and outcomes

Discussion

In Hong Kong, there are so far no published data on

the effect of reimbursement on booking and attendance rates for smoking

cessation programmes. Overseas studies have evaluated the effect of

reimbursement on quitting attempts and abstinence rates, but not

attendance at smoking cessation services. This study provides some

insights into this area.

The participants in the control and intervention

group were comparable except for mean age (62 vs 58 years) and duration of

smoking (41 vs 37 years). Simply offsetting the HK$45 SCCP fee with a

HK$50 supermarket coupon significantly increased smokers’ willingness to

join or actually book an SCCP session (OR=4.963 and 4.244, respectively) [Table 3]. This finding suggests that a financial

intervention may make more smokers consider joining an SCCP. With further

counselling and NRT in the SCCP, the road to successful smoking cessation

may be shortened.

The lack of an association between attendance rate

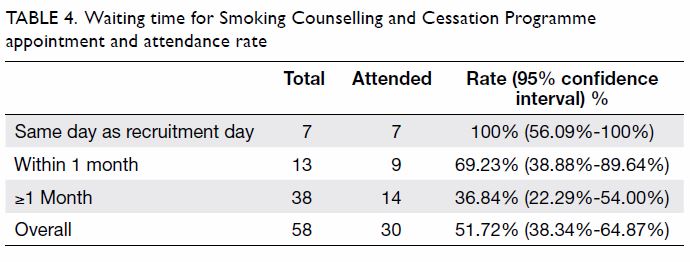

and reimbursement might be explained by the waiting time for SCCP (Table

4). Owing to human resource constraints, more than 65% of SCCP

appointments had to be scheduled for over a month after participant

recruitment. The mean waiting time was 37 days for the intervention group

and 33 days for the control group. The attendance rate dropped from 69% to

37% when the appointment date was over a month away. This finding was in

keeping with an overseas study that reported long waiting times as one of

the reasons for non-attendance at a quitting programme.23 Future local studies might involve exploring the

reasons for programme non-attendance and would help service providers to

improve the SCCP and help more smokers quit.

Table 4. Waiting time for Smoking Counselling and Cessation Programme appointment and attendance rate

In a local evaluative study of the integrated

smoking cessation services of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals in 2011, the

majority of clients (52.6%) consumed 11-20 CPD.24

More than half (54.4%) of those who attended smoking cessation clinics of

the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals had a high dependency on nicotine.24 In agreement, our study found that smokers consuming

11-20 CPD were significantly more likely to attend an SCCP than lighter

smokers (OR=4.443). We also found that smokers with shorter TTFC were

significantly more likely to agree to join or book an SCCP session (TTFC

≤5 minutes: OR=9.788 and 9.871, respectively; TTFC 6-30 minutes: OR=3.954,

and OR=4.916, respectively).

Individuals in the quitting preparation stage

display the highest motivation-ruler ratings.20

In our study, smokers with a higher rating of readiness were more likely

to have a higher rate of deciding to join, book, or attend an SCCP (Table

3). This finding indicates that smokers who were recruited to join

an SCCP were prepared to quit. Concerns that offering a financial

incentive might invite smokers who had no genuine intention to quit are

unfounded. Offering help to smokers for quitting was one of the MPOWER

(Monitor, Protect, Offer, Warn, Enforce, and Raise) measures described by

the World Health Organization to combat the global tobacco epidemic.25 Hong Kong is fortunate to have a well-established

smoking cessation programme, so the service deserves to be fully used.

Limitations

The smokers recruited into this study were a

convenience sample of attendees at GOPCs, so their characteristics would

differ from those of the general smoking population in Hong Kong15 in terms of a larger proportion of males (90.8% vs

83.9%), higher daily cigarette consumption (48.6% consuming 11-20 CPD vs

56.0% consuming 1-10 CPD), and larger proportion of economically inactive

smokers (38.7% vs 21.0%). The results thus may not be generalised to the

whole population of Hong Kong smokers. Furthermore, retirement and

economic inactivity may influence smoking habits26

and act as confounders, but these were not controlled in the multivariable

analyses.

The control and intervention groups were not very

comparable: the control group was slightly older and had smoked for

slightly longer. Estimation of the sample size was suboptimal, as the

total numbers of eligible smokers during the recruitment period and the

estimated increase in attendance rate by financial incentives were not

available before the study. Sample-size estimation was based on abstinence

rates from previous studies instead of attendance rates. The number of

participants who actually attended (19+11=30) may be too small to show any

statistical difference between SCCP attendance rates because the

difference was less than the three-fold increase for the sample-size

calculation.

In addition, the SCCP service in some clinics was

restricted to certain days or times of the week owing to availability of

counsellors. Some smokers, especially those who were working, may not have

been able to find a session at a convenient time. This situation could

have affected the booking and attendance rate between different clinics.

In one of the returned questionnaires in which the participant ticked the

box “agree to join SCCP” but did not make a booking, there was a written

remark in Chinese: “Time does not fit”.

This study was non-randomised and the doctors and

nurses were not blinded to the financial intervention, because of the

difficulty of running a complex workflow with limited resources. We

assumed all doctors and nurses tried their best to assist smokers to quit.

The possibility that those in the intervention group were more passionate

in persuading patients to quit smoking cannot be excluded. The assignment

of participants to the intervention or control group was not random and

may explain the differences in the baseline characteristics of

participants in the two groups. Moreover, it is unknown whether there

would be a difference in behaviour if free SCCP was offered from the

beginning, instead of providing a fixed-amount HK$50 supermarket coupon

that offered an extra HK$5. Only the 7-day quit rate was used as the final

programme outcome, as it was a standard outcome in the study centres.

Future research with a robust randomisation process may be considered, as

well as the use of longer abstinence periods such as 1 month, 3 months,

and 12 months.

Conclusion

This study revealed that provision of a financial

incentive that would indirectly cover the SCCP service fee might increase

the proportion of smokers who agree to attend and make a booking to attend

an SCCP. To reduce the barriers to accessing an SCCP service, budget

holders should consider providing free and timely SCCP to motivated

smokers. It is essential to catch smokers’ moment of hesitation and to

increase their access to the service.

Supplementary information

Online supplementary information (Appendices

1 and 2) is available for this article at www.hkmj.org.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians

(HKCFP) for granting the HKCFP Trainee Research Fund 2015 for this study.

We also thank the doctors and nurses in Cheung Sha Wan GOPC, Ha Kwai Chung

GOPC, Li Po Chun GOPC, West Kowloon GOPC, South Kwai Chung GOPC, and Tsing

Yi Cheung Hong GOPC for participant recruitment; Drs LS Chu, T Fong, KM

Ho, and SY Tse for advice during research design; and Ms Ellen Yu and Mr

Edward Choi for their support during the statistical analyses.

Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

References

1. National Center for Chronic Disease

Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The

Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: a Report of the

Surgeon General. 2014. Available from:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24455788. Accessed 6 Jun 2016.

2. Lam TH, Ho SY, Hedley AJ, et al.

Mortality and smoking in Hong Kong: case-control study of all adult deaths

in 1998. BMJ 2001;323:361. Crossref

3. McGhee SM, Ho LM, Lapsley HM, et al.

Cost of tobacco-related diseases, including passive smoking, in Hong Kong.

Tob Control 2006;15:125-30. Crossref

4. Lam TH. Absolute risk of tobacco deaths:

one in two smokers will be killed by smoking: comment on “Smoking and

all-cause mortality in older people”. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:845-6. Crossref

5. Simon JA, Carmody TP, Hudes ES, et al.

Intensive smoking cessation counseling versus minimal counseling among

hospitalized smokers treated with transdermal nicotine replacement: a

randomized trial. Am J Med 2003;114:555-62. Crossref

6. Ibrahim MI, N.A. Magzoub NA, Maarup N.

University-based smoking cessation program through pharmacist-physician

initiative: an economic evaluation. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:LC11-5.

7. Lancaster T, Stead LF. Individual

behavioural counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2005;(2)CD001292. Crossref

8. Cornuz J, Pinget C, Gilbert A, et al.

Cost-effectiveness analysis of the first-line therapies for nicotine

dependence. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2003;59:201-6. Crossref

9. Wang D, Connock M, Barton P, et al. ‘Cut

down to quit’ with nicotine replacement therapies in smoking cessation: a

systematic review of effectiveness and economic analysis. Health Technol

Assess 2008;12:iii-iv, ix-xi, 1-135.

10. Etter JF, Stapleton JA. Nicotine

replacement therapy for long-term smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Tob

Control 2006;15:280-5. Crossref

11. Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, et al.

Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2012;(11):CD000146. Crossref

12. Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR,

et al. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking

cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016(3):CD008286. Crossref

13. Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S, et al.

Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated

smokers. Addiction 2004;99:29-38. Crossref

14. Hong Kong Council on Smoking and

Health. Smoking Cessation Service Providers in Hong Kong. Available from:

http://smokefree.hk/en/content/web.do?page=Services. Accessed 7 Jun 2015.

15. Census and Statistics Department,

Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Thematic

Household Survey Report No. 59. Available from:

http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B11302592016XXXXB0100.pdf. Accessed 1 Jul

2016.

16. Edwards SA, Bondy SJ, Callaghan RC, et

al. Prevalence of unassisted quit attempts in population-based studies: a

systemic review of the literature. Addict Behav 2014;39:512-9. Crossref

17. Reda AA, Kotz D, Evers SM, et al.

Healthcare financing systems for increasing the use of tobacco dependence

treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(6):CD004305. Crossref

18. Dhalwani NN, Szatkowski L, Coleman T,

et al. Nicotine replacement therapy in pregnancy and major congenital

anomalies in offspring. Pediatrics 2015;135:859-67. Crossref

19. Borland R, Yong HH, O’Connor R, et al.

The reliability and predictive validity of the Heaviness of Smoking Index

and its two components: findings from the International Tobacco Control

Four Country study. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12 Suppl:S45-50. Crossref

20. Boudreaux ED, Sullivan A, Abar B, et

al. Motivation rulers for smoking cessation: a prospective observational

examination of construct and predictive validity. Addict Sci Clin Pract

2012;7:8. Crossref

21. Kaper J, Wagena EJ, Willemsen MC, et

al. A randomized controlled trial to assess the effects of reimbursing the

costs of smoking cessation therapy on sustained abstinence. Addiction

2006;101:1656-61. Crossref

22. Casagrande JT, Pike MC, Smith PG. An

improved approximate formula for calculating sample sizes for comparing

two binomial distributions. Biometrics 1978;34:483-6. Crossref

23. Sharp DJ, Hamilton W. Non-attendance

at general practices and outpatient clinics: Local systems are needed to

address local problems. BMJ 2001;323:1081-2. Crossref

24. Chan SC, Leung YP, Chan CH, et al. An

Evaluative Study of the Integrated Smoking Cessation Services of Tung Wah

Group of Hospitals. Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. 2011. Available from:

http://icsc.tungwahcsd.org/file/evaluative_study.pdf. Accessed 1 Jul 2016.

25. World Health Organization. WHO Report

on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2015: Raising Taxes on Tobacco. Available

from:

http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/178574/1/9789240694606_eng.pdf?ua=12015.

Accessed 1 Jul 2016.

26. Lang IA, Rice NE, Wallace RB, et al.

Smoking cessation and transition into retirement: analyses from the

English longitudinal study of ageing. Age Ageing 2007;36:638-43. Crossref