Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Feb;24(1):18–24 | Epub 5 Jan 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154764

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Implications of nipple discharge in Hong Kong Chinese

women

WM Kan, FCSHK, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

Clement Chen, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)2; Ava Kwong, FRCS, FHKAM

(Surgery)2

1 Department of Surgery, Queen Elizabeth

Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

2 Department of Surgery, Queen Mary

Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Ava Kwong (avakwong@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: There are no

recent data on nipple discharge and its association with malignancy in

Hong Kong Chinese women. This study reported our 5-year experience in

the management of patients with nipple discharge, and our experience of

mammography, ultrasonography, ductography, and nipple discharge cytology

in an attempt to determine their role in the management of nipple

discharge.

Methods: Women who attended our

Breast Clinic in a university-affiliated hospital in Hong Kong were

identified by retrospective review of clinical data from January 2007 to

December 2011. They were divided into benign and malignant subgroups.

Background clinical variables and investigative results were compared

between the two subgroups. We also reported the sensitivity,

specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the

investigations that included mammography, ultrasonography, ductography,

and cytology.

Results: We identified 71 and 31

patients in the benign and malignant subgroups, respectively. The median

age at presentation for the benign subgroup was younger than that of the

malignant subgroup (48 vs 59 years; P=0.003). A higher proportion of

patients in the malignant subgroup than the benign subgroup presented

with blood-stained nipple discharge (87.1% vs 47.9%; P=0.002).

Mammography had a specificity of 98.4% and positive predictive value of

66.7%; ultrasonography had a specificity of 87.0% and negative

predictive value of 75.0%. Cytology and ductography were sensitive but

lacked specificity. Ductography had a negative predictive value of 100%

but a low positive predictive value (14.0%). Clinical variables

including age at presentation, duration of discharge, colour of

discharge, presence of an associated breast mass, and abnormal

sonographic findings were important in suggesting the underlying

pathology of nipple discharge. Multiple logistic regression showed that

blood-stained discharge and an associated breast mass were statistically

significantly more common in the malignant subgroup.

Conclusions: In patients with

non–blood-stained nipple discharge, a negative clinical breast

examination combined with negative imaging could reasonably infer a

benign underlying pathology.

New knowledge added by this study

- Blood-stained nipple discharge and an associated breast mass at presentation could suggest a higher chance of malignancy.

- A period of watchful waiting is a reasonable alternative to surgical intervention in patients with inferred benign pathology.

Introduction

Nipple discharge is a relatively uncommon complaint

in Hong Kong Chinese women. According to a study in 1997, nipple discharge

constituted 1.5% of all presenting complaints for women who attended a

breast clinic in Hong Kong.1 On the

contrary, nipple discharge accounted for up to 4% to 7% of all presenting

symptoms in other studies.2 3 This may be better explained by the unique Chinese

culture and help-seeking pattern rather than a true disease pattern. With

this understanding, any clinical survey will probably underestimate the

prevalence of nipple discharge in Chinese women. When patients approach

health care professionals because of nipple discharge, not only is it

important to differentiate malignant from benign causes of nipple

discharge, it is also a valuable opportunity to promote breast health

awareness.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the relationship

between breast cancer and nipple discharge, with malignancy reported in up

to 9.3% to 21% of all patients who present with nipple discharge.4 5 The most

challenging role of breast surgeons is to accurately identify these

patients. Notwithstanding, controversy persists about the value and

accuracy of individual investigative tools for nipple discharge.6

There are no recent data on nipple discharge and

its association with malignancy in Chinese women in Hong Kong. The primary

aim of this study was to report our recent experience in the management of

patients with nipple discharge in a single surgical centre. The secondary

aim was to report our experience of individual investigative tools in an

attempt to determine their role in the management of nipple discharge.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical data of

patients who attended our Breast Clinic at the Queen Mary Hospital, a

university-affiliated hospital in Hong Kong, for nipple discharge from

January 2007 to December 2011. Potential subjects were identified when

diagnosis coding 611.79 (other signs and symptoms in breast) was entered

into our Clinical Management System, which is a territory-wide

computer-based medical record system designed for use in public hospitals,

and also from the prospective database of the Division of Breast Surgery,

The University of Hong Kong.

Data extraction and coding were performed by the

first author (WM Kan) and included duration of follow-up until December

2011, age at presentation, history of breast condition, and laterality and

duration of nipple discharge before first consultation. Clinical variables

included colour of nipple discharge, single- or multiple-duct discharge,

associated symptoms, mammographic and ultrasonographic imaging results, as

well as ductogram and cytology results. Pathology results were recorded

for patients who underwent surgery or biopsy.

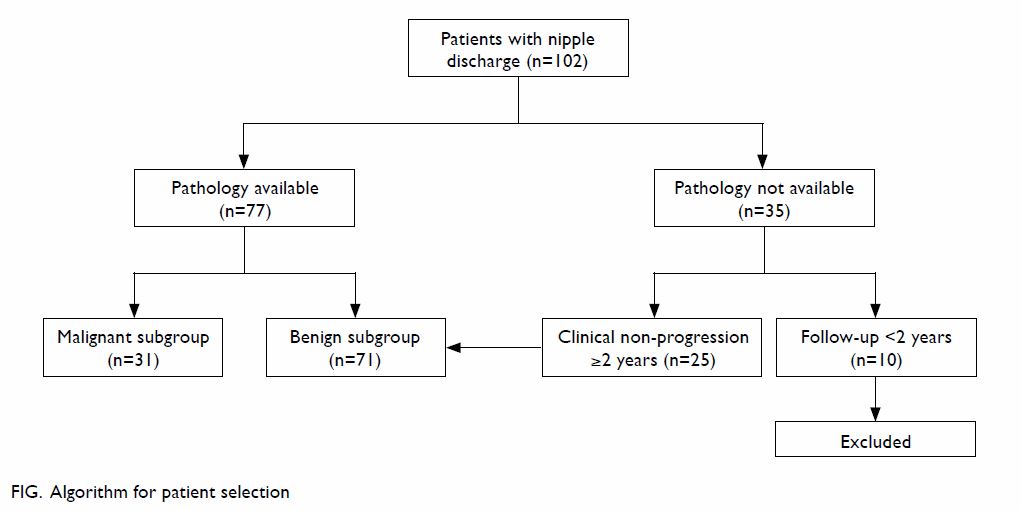

In order to make a meaningful comparison, we

divided patients into malignant and benign subgroups. The malignant

subgroup was defined by malignant pathology on a surgically resected

specimen. The benign subgroup was defined by benign pathology of a

surgically resected or biopsy specimen, or clinical non-progression after

more than 2 years of follow-up. Patients who did not undergo surgery or

biopsy and who were followed up for less than 2 years were excluded (Fig).

In the first part of our study, we compared the

background clinical variables and investigative results between the two

subgroups. In the second part of our analysis, we reported the

sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative

predictive value of individual investigative tools.

For the purpose of this analysis, we also

classified the results of clinical examination, mammography,

ultrasonography, and cytology as ‘test positive’ or ‘test negative’ for

underlying malignancy. Presence of a palpable breast mass (regardless of

mobility) was considered a positive result and no palpable breast mass a

negative result. For mammographic findings, microcalcifications were

considered a positive result. For ultrasonography, a detectable mass was

‘test positive’ for underlying malignancy; non-solitary dilated ducts,

cysts, and normal ultrasonogram were regarded as ‘test negative’. For

ductogram results, dilated ducts, irregularity, and the presence of ductal

filling defects were considered positive. For cytology, atypical,

suspicious, and malignant were considered ‘test positive’, and benign as

‘test negative’. This study was done in accordance with the principles

outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

R version 3.0.2 (the R Foundation) and the SPSS

(Windows version 14.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], United States) were used

for data analysis. To determine the differences between subgroups,

Wilcoxon rank sum test and Fisher’s exact test were used for numerical

data and categorical data, respectively. Multiple logistic regression was

performed to examine the odds ratios of the factors. Backward selection

through likelihood ratio test with removal of P value of 0.1 was conducted

for model selection. Variables in univariate analysis with a P value of

<0.1 were included in the full model. A P value of <0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

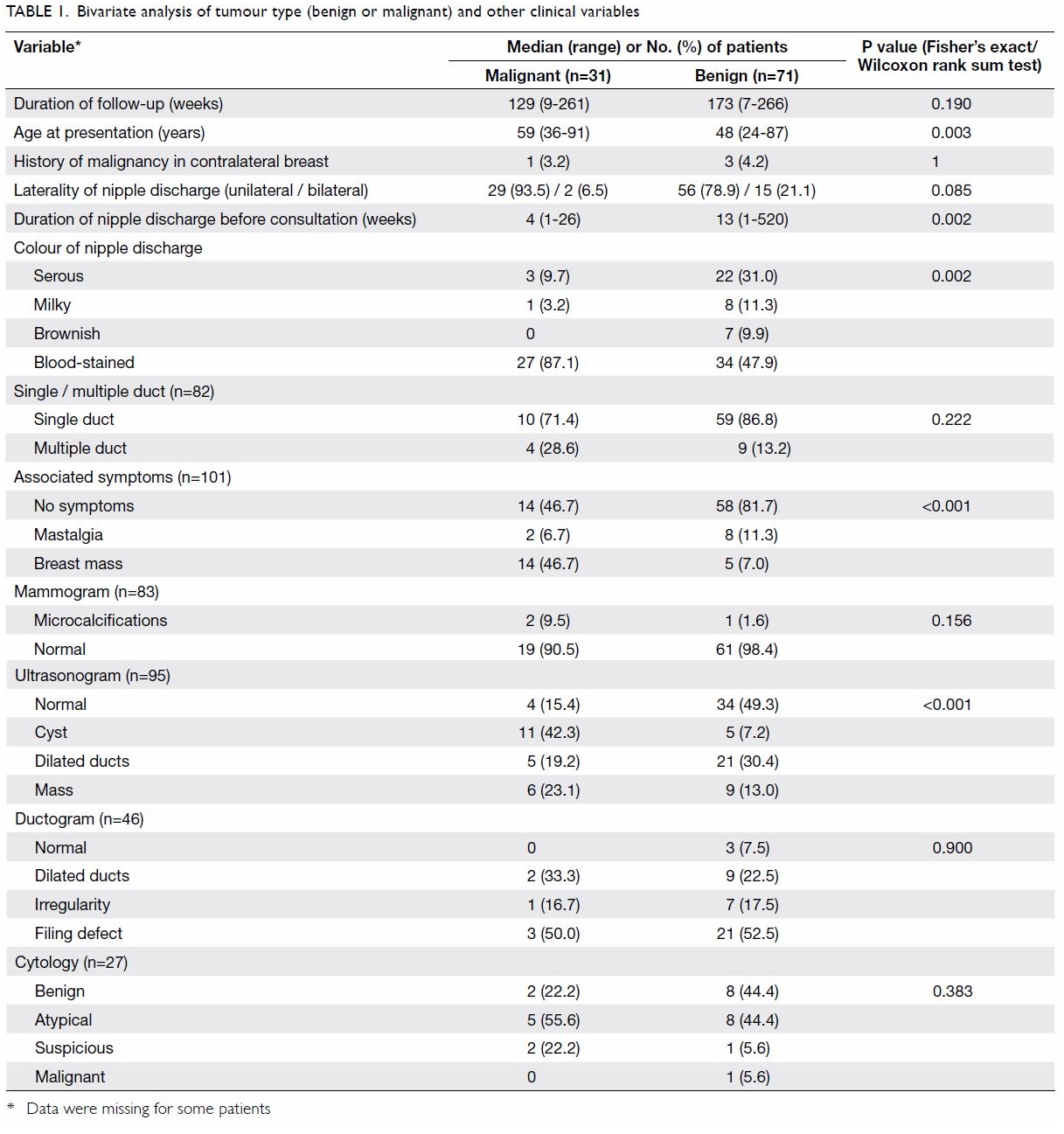

Table 1 summarises the first part of our analysis.

We identified 102 patients who presented to our Breast Clinic during the

study period. They had either a tissue diagnosis or had been followed up

for longer than 2 years without tissue diagnosis. There were 31 and 71

patients in the malignant and benign subgroups, respectively.

The median age at presentation of the benign

subgroup was significantly younger than that of the malignant subgroup (48

vs 59 years; P=0.003). The median interval between onset of nipple

discharge and first presentation was significantly longer in the benign

subgroup than in the malignant subgroup (13 vs 4 weeks; P=0.002).

Comparing the two subgroups, a larger proportion of

patients in the malignant subgroup presented with blood-stained discharge

(87.1% vs 47.9%; P=0.002) and had a breast mass at presentation (46.7% vs

7.0%; P<0.001). For the individual investigative modalities, with the

exception of ultrasonography, neither mammography, ductography nor

cytology showed any statistically significant difference between the

malignant and benign subgroups.

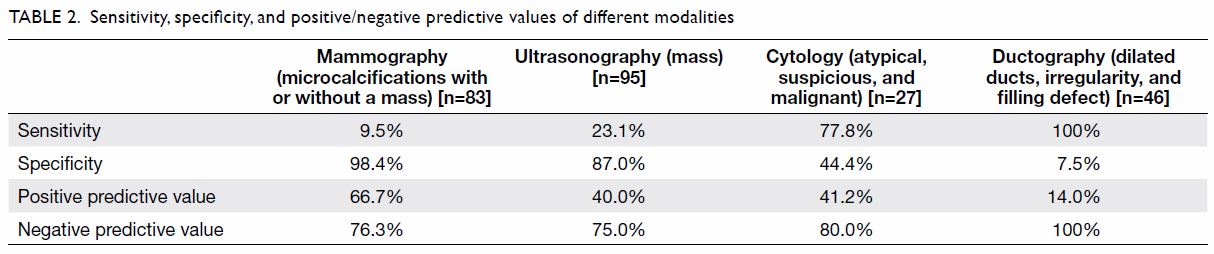

Table 2 summarises the second part of the study. We

calculated the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative

predictive values of mammographic, ultrasonographic, cytological, and

ductographic findings. There were 83, 95, 27, and 46 patients who

underwent mammography, ultrasonography, cytology, and ductography,

respectively. The positive and negative predictive values of cytology were

41.2% and 80.0%, respectively. Ductography had a sensitivity of 100%,

specificity of 7.5%, positive predictive value of 14.0%, and negative

predictive value of 100%.

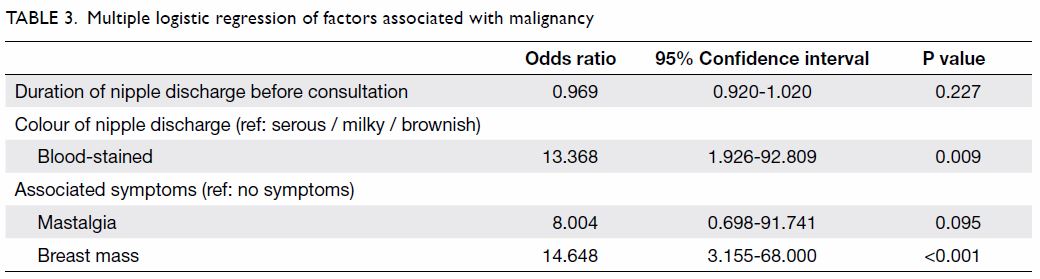

Multiple logistic regression analysis with backward

selection was performed. Covariates with a P value of <0.1 were

included in the full model (Table 1). By likelihood ratio test and removal of

variables with a P value of >0.1, duration of nipple discharge, colour

of nipple discharge, mastalgia, and associated mass remained in the final

model (Table 3).

Compared with serous, milky and brownish discharge,

patients with blood-stained discharge had a significantly higher risk for

malignancy (odds ratio=13.368; 95% confidence interval, 1.926-92.809). In

addition, compared with patients having no symptoms, those with a breast

mass had a significantly higher risk for malignancy (odds ratio=14.648;

95% confidence interval, 3.155-68.000) [Table 3].

Discussion

A methodologically ideal study of nipple discharge

would require every patient to undergo the same investigations and also

surgery for final pathology. This, however, would be unethical. For

patients who opted for non-operative management of nipple discharge, our

retrospective study considered 2-year clinical non-progression a

reasonable surrogate for benign breast pathology.

Clinical variables

Women in the malignant subgroup were significantly

older at presentation than their benign counterparts. This was in

agreement with the fact that physiological nipple discharge is more common

in younger premenopausal women. Caution should be exercised in

postmenopausal women who present with nipple discharge and the possibility

of malignancy investigated before concluding a benign pathology.

With respect to the colour of nipple discharge,

underlying benign and malignant causes had a different pattern. Benign

pathology was more likely to be associated with non–blood-stained

discharge (n=37, 52.1%), whereas malignant pathology was more likely to be

associated with blood-stained discharge (n=27, 87.1%). This is not

pathognomonic but did reach statistical significance.

The differentiation between multiple-duct and

single-duct discharge showed no association with underlying pathology.

Mammography and ultrasonography

As shown in Table 2, mammography had a higher specificity of

98.4% and positive predictive value of 66.7% but a disappointingly low

sensitivity of 9.5%. Therefore, a normal mammogram did not confidently

exclude malignancy. On the other hand, breast ultrasonography had a

specificity and negative predictive value of 87.0% and 75.0%,

respectively. Mammography was routinely offered to patients who presented

with nipple discharge. Complementary breast ultrasonography was also

arranged, especially for younger Asian women with denser breasts on

mammography.7 In our experience,

complementary ultrasonography increases the overall sensitivity and

negative predictive value compared with mammography alone.

Nipple discharge cytology

Opinion is divided on the value of cytological

examination. While some studies report a complementary diagnostic value

and recommend its routine use,8 9 others report it has little such

value and advise against its routine use.10

Of the 102 patients, 36 had demonstrable nipple

discharge at consultation with a sample collected for examination. Of

these 36 specimens, only 27 showed a sufficient number of cells to make a

cytological diagnosis. Nonetheless, we attempted to analyse its accuracy.

The sensitivity and specificity of cytological examination were 77.8% and

44.4%, respectively. Its positive predictive value was disappointingly low

at 41.2% and its negative predictive value was 80.0%. The diagnostic value

of this investigation was limited as not every patient had demonstrable

nipple discharge and not every specimen contained adequate cells for

testing. Nonetheless, this investigation is minimally invasive so was

always performed if there was demonstrable nipple discharge, although it

rarely affected the clinical decision or plan of management.

Ductography

The value of ductography is debatable. While some

studies have validated the diagnostic value of preoperative ductography in

differentiating benign and malignant pathology,11

12 others doubt its value.13 Rather than differentiating benign and malignant

pathology, we used preoperative ductogram to aid in the localisation of

non-palpable lesions.14 15 The sensitivity was 100% whereas the specificity was

low at 7.5%, with a positive predictive value of 14.0% and a negative

predictive value of 100%.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging was not included in our

routine evaluation of patients with nipple discharge although we

acknowledge its value in the detection of carcinoma in these patients. It

has an exceptionally high sensitivity for both invasive and in-situ

carcinoma.16 Its routine use in

patients with a breast lesion is nonetheless limited by its relatively low

specificity of 72% (95% confidence interval, 67%-77%).17 The role of magnetic resonance imaging in patients

with nipple discharge has been extensively validated,18 19 20 21

suggesting that it may detect or exclude the presence of carcinoma with a

high degree of certainty. Magnetic resonance imaging may be considered

when all other available strategies are inconclusive.

Microdochectomy

Emerging evidence suggests that neither clinical

variables nor preoperative investigations reliably distinguish benign and

malignant pathology so duct excision should be offered to every patient

with nipple discharge.22 23 24 25 26 We

offered microdochectomy to patients with no palpable breast lesion based

on two indications: clinical or radiological suspicion, or a patient’s

wish to stop nipple discharge by surgery. It is likely that offering

microdochectomy to all patients with nipple discharge would result in

overtreatment as the final pathology was benign in most cases. In

patients with negative clinical examination and negative imaging findings,

a period of watchful waiting with regular follow-up is a reasonable

alternative to surgical intervention.

The association of blood-stained discharge with

malignancy is controversial. Morrogh et al24

reported that haemorrhagic discharge did not indicate malignancy or high

risk, and non-haemorrhagic discharge did not exclude malignancy. In our

study, we showed that blood-stained discharge was associated with

malignancy but was not pathognomonic.

On the other hand, presence of an associated breast

mass was a significant finding. This may be because it is the most common

presenting symptom of breast cancer, and its incidence rises with age.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, as data

collection was retrospective, there might have been inconsistent or

incomplete recording of clinical findings. Study subjects might not be

representative and some data for importable variables might have been

missing. No blinding during information extraction or coding could be

achieved as it was performed by the first author. Second, the small sample

size limited the power of our study although this could in part be due to

the relatively conservative culture and help-seeking pattern of Hong Kong

Chinese women. The unequal arm size also limited the interpretation of

statistical significance of comparisons. Third, our assumption of 2-year

clinical non-progression as benign pathology might have underestimated the

true incidence of malignancy in our group of patients. Lastly, the small

number of adequate cytology specimens limited meaningful analysis of this

investigation. As the sample taken for cytology is usually small, it will

affect the sensitivity.

Conclusions

Clinical variables including age at presentation,

duration and colour of discharge, presence of an associated breast mass,

and abnormal sonographic findings were important in suggesting the

underlying pathology of nipple discharge. Only blood-stained nipple

discharge and an associated breast mass remained in the multiple logistic

regression model and were statistically significant. In patients with

non–blood-stained nipple discharge, as well as a negative clinical breast

examination and imaging, we may infer an underlying benign pathology.

Further prospective studies with a larger sample size are advocated.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr Wing-pan Luk and

Mr Ling-hiu Fung, Medical Physics & Research Department, Hong Kong

Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong for their statistical contribution to

this paper.

References

1. Cheung KL, Alagaratnam TT. A review of

nipple discharge in Chinese women. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1997;42:179-81.

2. Murphy IG, Dillon MF, Doherty AO, et al.

Analysis of patients with false negative mammography and symptomatic

breast carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 2007;96:457-63. Crossref

3. Vargas HI, Vargas MP, Eldrageely K,

Gonzalez KD, Khalkhali I. Outcomes of clinical and surgical assessment of

women with pathological nipple discharge. Am Surg 2006;72:124-8.

4. Murad TM, Contesso G, Mouriesse H.

Nipple discharge from the breast. Ann Surg 1982;195:259-64. Crossref

5. King TA, Carter KM, Bolton JS, Fuhrman

GM. A simple approach to nipple discharge. Am Surg 2000;66:960-6.

6. Jain A, Crawford S, Larkin A, Quinlan R,

Rahman RL. Management of nipple discharge: technology chasing application.

Breast J 2010;16:451-2. Crossref

7. Kwong A, Cheung PS, Wong AY, et al. The

acceptance and feasibility of breast cancer screening in the East. Breast

2008;17:42-50. Crossref

8. Pritt B, Pang Y, Kellogg M, St. John T,

Elhosseiny A. Diagnostic value of nipple cytology: study of 466 cases.

Cancer 2004;102:233-8. Crossref

9. Kalu ON, Chow C, Wheeler A, Kong C,

Wapnir I. The diagnostic value of nipple discharge cytology: breast

imaging complements predictive value of nipple discharge cytology. J Surg

Oncol 2012;106:381-5. Crossref

10. Kooistra BW, Wauters C, van de Ven S,

Strobbe L. The diagnostic value of nipple discharge cytology in 618

consecutive patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2009;35:573-7. Crossref

11. Hou MF, Huang TJ, Liu GC. The

diagnostic value of galactography in patients with nipple discharge. Clin

Imaging 2001;25:75-81. Crossref

12. Hou MF, Huang CJ, Huang YS, et al.

Evaluation of galactography for nipple discharge. Clin Imaging

1998;22:89-94. Crossref

13. Dawes LG, Bowen C, Venta LA, Morrow M.

Ductography for nipple discharge: no replacement for ductal excision.

Surgery 1998;124:685-91. Crossref

14. Peters J, Thalhammer A, Jacobi V, Vogl

TJ. Galactography: an important and highly effective procedure. Eur Radiol

2003;13:1744-7. Crossref

15. Lamont JP, Dultz RP, Kuhn JA, Grant

MD, Jones RC. Galactography in patients with nipple discharge. Proc (Bayl

Univ Med Cent) 2000;13:214-6. Crossref

16. Heywang-Koebrunner SH. Diagnosis of

breast cancer with MR—review after 1250 patients. Electromedica

1993;61:43-52.

17. Peters NH, Borel Rinkes IH, Zuithoff

NP, Mali WP, Moons KG, Peeters PH. Meta-analysis of MR imaging in the

diagnosis of breast lesions. Radiology 2008;246:116-24. Crossref

18. Orel SG, Dougherty CS, Reynolds C,

Czerniecki BJ, Siegelman ES, Schnall MD. MR imaging in patients with

nipple discharge: initial experience. Radiology 2000;216:248-54. Crossref

19. Nakahara H, Namba K, Watanabe R, et

al. A comparison of MR imaging, galactography and ultrasonography in

patients with nipple discharge. Breast Cancer 2003;10:320-9. Crossref

20. Hirose M, Otsuki N, Hayano D, et al.

Multi-volume fusion imaging of MR ductography and MR mammography for

patients with nipple discharge. Magn Reson Med Sci 2006;5:105-12. Crossref

21. Ballesio L, Maggi C, Savelli S, et al.

Role of breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with

unilateral nipple discharge: preliminary study [in English, Italian].

Radiol Med 2008;113:249-64. Crossref

22. Adepoju LJ, Chun J, El-Tamer M,

Ditkoff BA, Schnabel F, Joseph KA. The value of clinical characteristics

and breast-imaging studies in predicting a histopathologic diagnosis of

cancer or high-risk lesion in patients with spontaneous nipple discharge.

Am J Surg 2005;190:644-6. Crossref

23. Lanitis S, Filippakis G, Thomas J,

Christofides T, Al Mufti R, Hadjiminas DJ. Microdochectomy for single-duct

pathologic nipple discharge and normal or benign imaging and cytology.

Breast 2008;17:309-13. Crossref

24. Morrogh M, Park A, Elkin EB, King TA.

Lessons learned from 416 cases of nipple discharge of the breast. Am J

Surg 2010;200:73-80. Crossref

25. Alcock C, Layer GT. Predicting occult

malignancy in nipple discharge. ANZ J Surg 2010;80:646-9. Crossref

26. Foulkes RE, Heard G, Boyce T, Skyrme

R, Holland PA, Gateley CA. Duct excision is still necessary to rule out

breast cancer in patients presenting with spontaneous bloodstained nipple

discharge. Int J Breast Cancer 2011;2011:495315. Crossref