DOI: 10.12809/hkmj175078

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

EDITORIAL

Living-related renal transplantation in Hong Kong

KF Chau, FRCP (Lond, Glasg, Edin)

Department of Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital,

Jordan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KF Chau (ckfz02@ha.org.hk)

Renal transplantation is the best treatment for

end-stage renal disease, as it allows optimum rehabilitation with better

survival than haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis: in 2016, the annual

mortality rate per 100 patient-years in Hong Kong was 1.88 for patients

who received a renal transplant, 17.89 for patients on peritoneal

dialysis, and 18.89 for those on haemodialysis.1

With a global shortage of cadaveric organs, living-related kidney donation

has become an important alternative, especially in countries with a low

cadaveric organ donation rate such as Japan. In Hong Kong, living-related

kidney transplants account for an average of 14.8% of all renal

transplants performed over the past 10 years.1

In this issue of the Hong Kong Medical Journal, the

characteristics and clinical outcomes of living renal donors in Hong Kong

are reported.2

Compared with a cadaveric kidney transplant, a

living-related kidney transplant has a higher graft survival rate: the

10-year graft survival rate was 70% for cadaveric and 81% for living

kidney transplant, and the 20-year graft survival rate was 44% for

cadaveric and 61% for living kidney transplant.1

This is due to multiple factors that include matching for the most

suitable donor, and elective surgery to minimise stress to the donor and

cold ischaemic time of the kidney. According to the Hospital Authority

Renal Registry, in 2016 the half-life of a cadaveric kidney transplant was

18 years, whereas that for a living kidney transplant was 30 years.1 Living-related kidney donation, however, carries

potential risks to the donor. The short-term risks include those related

to anaesthesia, bleeding, and infection. In the long term, there is an

increased risk of hypertension and proteinuria,3

4 as well as hypertension,

pre-eclampsia, and proteinuria during pregnancy.5

Laparoscopic nephrectomy rather than an open

procedure is now the preferred approach in many transplant centres for

living-kidney procurement. Comparative studies have shown a shorter

hospital stay and less bleeding, although the ischaemic time is longer

with the laparoscopic approach.6

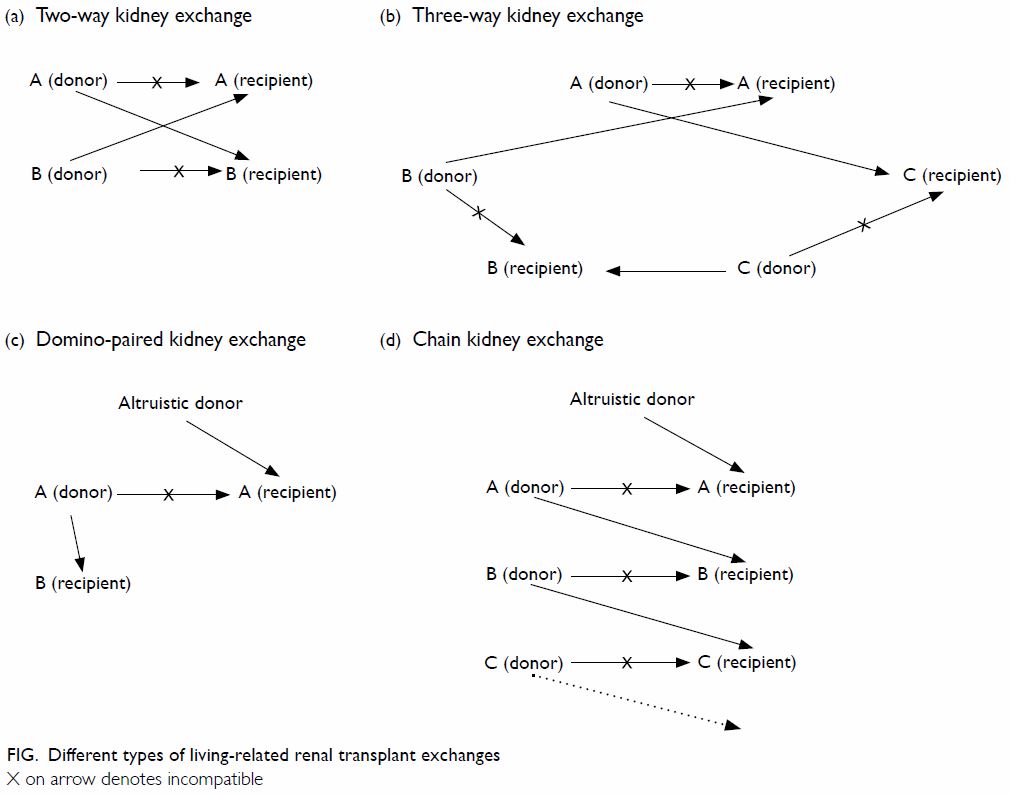

In order to overcome the problem of ABO blood group

or human leukocyte antigen incompatibility in living-related organ

donation, paired kidney exchange is becoming popular in many countries. It

may be a simple two-way exchange, a three-way exchange or, if an

altruistic donor is available, a domino-paired exchange or altruistic

donor chain (Fig). The longest chain was in 2012 in the United

States and involved 30 kidneys and 60 patients. In preparation for paired

kidney exchange in Hong Kong, the Food and Health Bureau plans to clarify

the legal situation by submitting a proposal to the Legislative Council.

Another means by which to overcome ABO blood group incompatibility is by a

pre-transplant immunosuppressive protocol that includes plasmapheresis

alone or together with rituximab.

Because of the potential risks to the donor, a

cadaveric kidney is still preferred. In 2016, the cadaveric organ donation

rate was 6.3 per million population in Hong Kong.1

Owing to the increasing gap between the number of patients requiring a

transplant and the number of organs available, the waiting time for a

cadaveric organ is increasing. The average waiting time is approximately 6

years but may also be as long as 28 years.1

Public education is essential to raise general awareness of the need for

cadaveric organ donation. Other measures include increasing human

resources for organ procurement in acute care hospitals, increasing the

effectiveness of donor referral and management and organ procurement, and

establishing an independent organ procurement organisation. These

initiatives are vital in order to boost organ donation rate in Hong Kong.

Declaration

The author has disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Hong Kong Hospital Authority Renal

Registry; 2016.

2. Hong YL, Yee CH, Leung CB, et al.

Characteristics and clinical outcomes of living renal donors in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong Med J 2018;24:11-7. Crossref

3. Chu KH, Poon CK, Lam CM, et al.

Long-term outcomes of living kidney donors: a single centre experience of

29 years. Nephrology (Carlton) 2012;17:85-8. Crossref

4. Okamoto M, Akioka K, Nobori S, et al.

Short- and long-term donor outcomes after kidney donation: analysis of 601

cases over a 35-year period at Japanese single center. Transplantation

2009;87:419-23. Crossref

5. Ibrahim HN, Akkina SK, Leister E, et al.

Pregnancy outcomes after kidney donation. Am J Transplant 2009;9:825-34. Crossref

6. Fonouni H, Mehrabi A, Golriz M, et al.

Comparison of the laparoscopic versus open live donor nephrectomy: an

overview of surgical complications and outcome. Langenbecks Arch Surg

2014;399:543-51. Crossref