Hong Kong Med J 2017 Oct;23(5):470–9 | Epub 4 Aug 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164684

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Assessment of dietary food and nutrient intake

and bone density in children with eczema

TF Leung, MD, FRCPCH1;

SS Wang, PhD1; Flora YY Kwok, MPhil1; Lesley WS Leung, BSc2; CM Chow, MB, ChB1; KL Hon, MD, FAAP1

1 Department of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince

of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Faculty of Science, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria,

Australia

Corresponding author: Dr TF Leung (tfleung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Dietary restrictions are common

among patients with eczema, and such practice may

lead to diminished bone mineral density. This study

investigated dietary intake and bone mineral density

in Hong Kong Chinese children with eczema.

Methods: This cross-sectional and observational

study was conducted in a university-affiliated

teaching hospital in Hong Kong. Chinese children

aged below 18 years with physician-diagnosed

eczema were recruited from our paediatric allergy

and dermatology clinics over a 6-month period in

2012. Subjects with stable asthma and/or allergic

rhinitis who were free of eczema and food allergy

as well as non-allergic children were recruited from

attendants at our out-patient clinics as a reference

group. Intake of various foods and nutrients was

recorded using a food frequency questionnaire

that was analysed using Foodworks Professional

software. Bone mineral density at the radius and the

tibia was measured by quantitative ultrasound bone

sonometry, and urinary cross-linked telopeptides

were quantified by immunoassay and corrected for

creatinine level.

Results: Overall, 114 children with eczema

and 60 other children as reference group were

recruited. Eczema severity of the patients was

classified according to the objective SCORing

Atopic Dermatitis score. Males had a higher daily

energy intake than females (median, 7570 vs 6736

kJ; P=0.035), but intake of any single food item or

nutrient did not differ between them. Compared

with the reference group, children with eczema had

a higher intake of soybeans and miscellaneous dairy

products and lower intake of eggs, beef, and shellfish.

Children with eczema also consumed less vitamin D,

calcium, and iron. The mean (standard deviation)

bone mineral density Z-score of children with

eczema and those in the reference group were 0.52

(0.90) and 0.55 (1.12) over the radius (P=0.889), and

0.02 (1.03) and –0.01 (1.13) over the tibia (P=0.886),

respectively. Urine telopeptide levels were similar

between the groups. Calcium intake was associated

with bone mineral density Z-score among children

with eczema.

Conclusions: Dietary restrictions are common

among Chinese children with eczema in Hong Kong,

who have a lower calcium, vitamin D, and iron intake.

Nonetheless, such practice is not associated with

changes to bone mineral density or bone resorptive

biomarker.

New knowledge added by this study

- Hong Kong children with moderate-to-severe eczema had a lower consumption of eggs, beef, and shellfish as well as vitamin D, calcium, and iron.

- Children with eczema had an increased intake of soybean and miscellaneous dairy products.

- These changes in dietary and nutrient intake were not associated with altered bone mineral density or urinary levels of cross-linked N-telopeptides of type 1 collagen in our children with eczema.

- Nutritional assessment and counselling should be offered to parents with children who have moderate-to-severe eczema.

- Children with eczema who have extensive food avoidance or impaired growth should undergo allergy evaluation so that their family can follow evidence-based advice about dietary modification.

- Bone mineral density assessment is unnecessary for the majority of children with eczema.

Introduction

Eczema is a chronic inflammatory skin disease

associated with cutaneous hyperreactivity to

environmental stimuli such as microbial exposure

and food ingestion that are otherwise tolerated by

unaffected subjects.1 In our community study, nearly one third of preschool children had eczema and 8.1%

had parent-reported adverse food reactions.2 Thus,

there is a significant health care burden from both

eczema and food allergy in Hong Kong. Food allergy

is believed by many patients and their family to be

a major cause of eczema. Many traditional Chinese medicine practitioners also advise extensive food

avoidance for eczema. Our previous study reported

that over half of local children with eczema practised

food avoidance.3 There are, however, limited

objective data on the intake of specific food items

and nutrients in children with eczema. Henderson

and Hayes4 reported the correlation between dietary

calcium intake and bone mineral density (BMD) in

55 children and adolescents aged 5 to 14 years with

cow’s milk sensitisation. Their calcium intake was

determined using a food frequency questionnaire

(FFQ). The bone density Z-score of their patients

with a milk allergy serially increased with increasing

calcium intake. In another study, Jensen et al5

investigated BMD in children aged 8 to 17 years

with verified cow’s milk allergy (CMA) for more

than 4 years and compared them with 343 healthy

controls. Their patient’s BMD was markedly reduced

for age, and height for age was reduced indicating

‘short’ bones. Furthermore, calcium consumption

was about 25% of that recommended. In another

study, BMD was assessed in 27 young children with

CMA.6 During bone resorption, osteoclasts secrete

a mixture of acid and neutral proteases that degrade

the collagen fibrils into molecular fragments

including C-terminal telopeptide. Its aspartic acid

changes from alpha to beta form as bone ages.

The latter form called beta-crosslaps is a specific marker for bone resorption; its concentration was

lower in CMA patients than in controls, indicating

an increased bone turnover in the former. Ten CMA

patients had a BMD Z-score of less than –1 standard

deviation (SD) value. Despite these results, there

was limited evidence of compromised bone health

in eczema patients when such results were adjusted

for confounders such as calcium intake and physical

activity. This study investigated intake of food items

and nutrients as well as BMD in Chinese children

in Hong Kong with varying degrees of eczema, and

compared these values with unaffected children.

Methods

Study population

This cross-sectional study recruited ethnic Chinese

children aged below 18 years with physician-diagnosed

eczema from our paediatric allergy and

dermatology clinics over a 6-month period in 2012.

Eczema was diagnosed using standard criteria,7 and

disease severity was assessed by SCORing Atopic

Dermatitis.8 Patients were treated with topical

mometasone furoate only. Those prescribed other

topical steroids were changed to this drug for at

least 4 weeks before the study. Patients prescribed

oral immunosuppressive drugs within 6 months

were excluded. Subjects with stable asthma and/or allergic rhinitis who were free of eczema and

food allergy as well as non-allergic children were

recruited from attendants at our out-patient clinics

as a reference group. As an inclusion criterion,

subjects in the reference group had no dietary

restrictions. Following informed written consent,

our research staff recorded subjects’ intake of a wide

spectrum of dietary components using a Chinese

FFQ. Children who attended secondary school and

beyond were assessed using the adolescent/adult

version,9 10 whereas those in primary schools and

below were assessed using the preschool version.11

Intake of individual food items and groups of major

nutrients as recorded in FFQ were quantified and

analysed by Foodworks Professional software

(version 7; Xyris, Brisbane, Australia). This software

included only certain Chinese food items commonly

found in Australia. Thus, our co-author (FYYK), who

has a dietetic qualification, added new Chinese food

data with reference to a comprehensive Chinese

food composition database published in 2004 by

the Peking University Medical Press (available

upon request). These new food items were saved in

the software as a new food composition database

so that their nutrient data could be computed.

Physical activity level of participants was assessed

using a Physical Self-Description Questionnaire.12

The study was approved by the Clinical Research

Ethics Committee of our university. All participants

provided written informed consent.

Urinary concentration of cross-linked

N-telopeptides of type 1 collagen

Urinary concentrations of cross-linked N-telopeptides

of type 1 collagen (NTx), biomarkers of

bone resorption,13 were measured by enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (Wampole Laboratories,

Princeton [NJ], US) with a lower limit of detection

set at 20 nM of bone collagen equivalent. Results

were corrected for creatinine that was measured by

modified Jaffe reaction (Roche Diagnostics GmbH,

Mannheim, Germany).

Bone mineral density measurement

Participants’ BMD was measured at the mid-point

of the radius in the non-dominant arm and at the left

tibia using quantitative ultrasound bone sonometry

(QUBS) to determine the velocity of ultrasound

wave, expressed as the speed of sound in m/s, using

Omnisense 7000P (BeamMed, Petach Tikva, Israel)

as described previously.14 15 This machine compared

speed of sound measurements to a built-in reference

database of a healthy urban Chinese population of

797 boys and 760 girls aged 0 to 18 years. As described

in the manufacturer’s manual, subjects with previous

osteoporotic fractures, use of medications affecting

bone health, presence of a disease known to affect

bone metabolism, recent prolonged immobilisation,

or a systemic malignant disease within 5 years

were excluded from such reference database. The

Omnisense devices were transported from place to

place, and the same group of operators performed all

measurements. Results of BMD were then expressed as age- and gender-matched Z-score.

Statistical analysis

Dietary food and nutrient intake, BMD Z-scores,

and urine NTx levels between different groups were

analysed by Student’s t test or analysis of variance

(ANOVA). The relationship between eczema and

dietary, BMD, and urinary variables that differed

significantly between children with eczema and

those in the reference group were confirmed by

multivariable stepwise binary logistic regression

adjusted for age, gender, body mass index (BMI),

physical activity level, and co-morbid allergic

diseases as covariates. The correlations between

clinical variables, BMD Z-scores, and urine NTx

levels were analysed by Pearson correlation.

Continuous variables with skewed data distribution

were transformed to achieve normal distribution

prior to analyses. All analyses were performed with

the use of SPSS (Windows version 18.0; SPSS Inc,

Chicago [IL], US). The level of significance was set at

0.05, and all P values were two-tailed.

Results

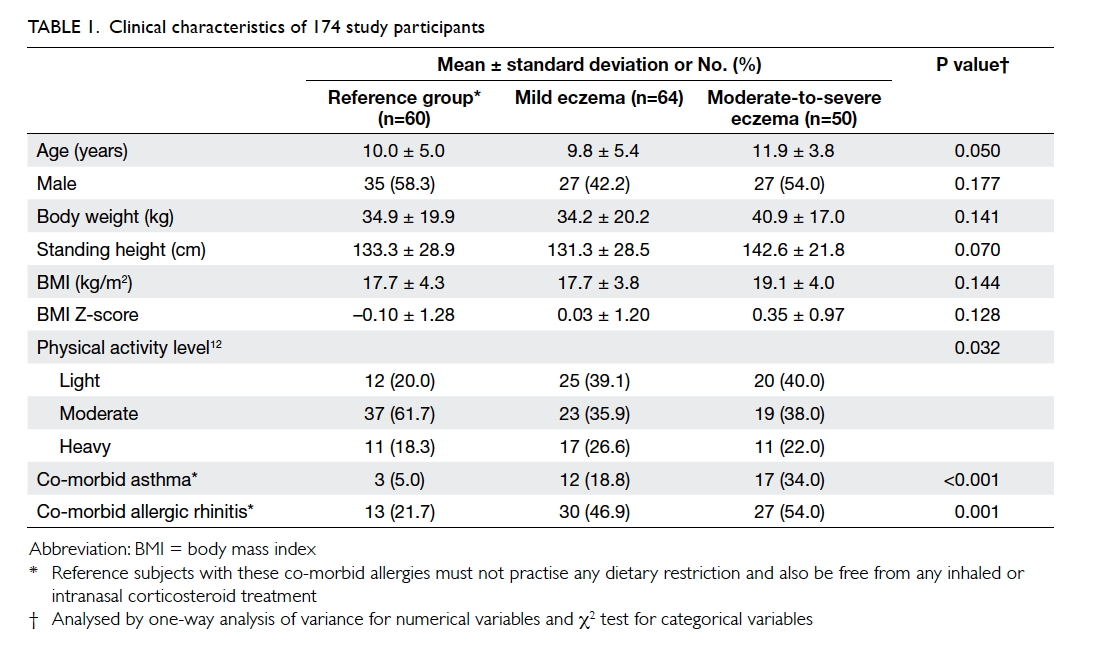

A total of 114 children with eczema and other 60

children as the reference group were recruited

(Table 1). The means (± SDs) age of children in the

reference group, children with mild eczema, and

children with moderate-to-severe eczema were 10.0

± 5.0, 9.8 ± 5.4, and 11.9 ± 3.8 years, respectively.

Age, gender, and anthropometric variables did not

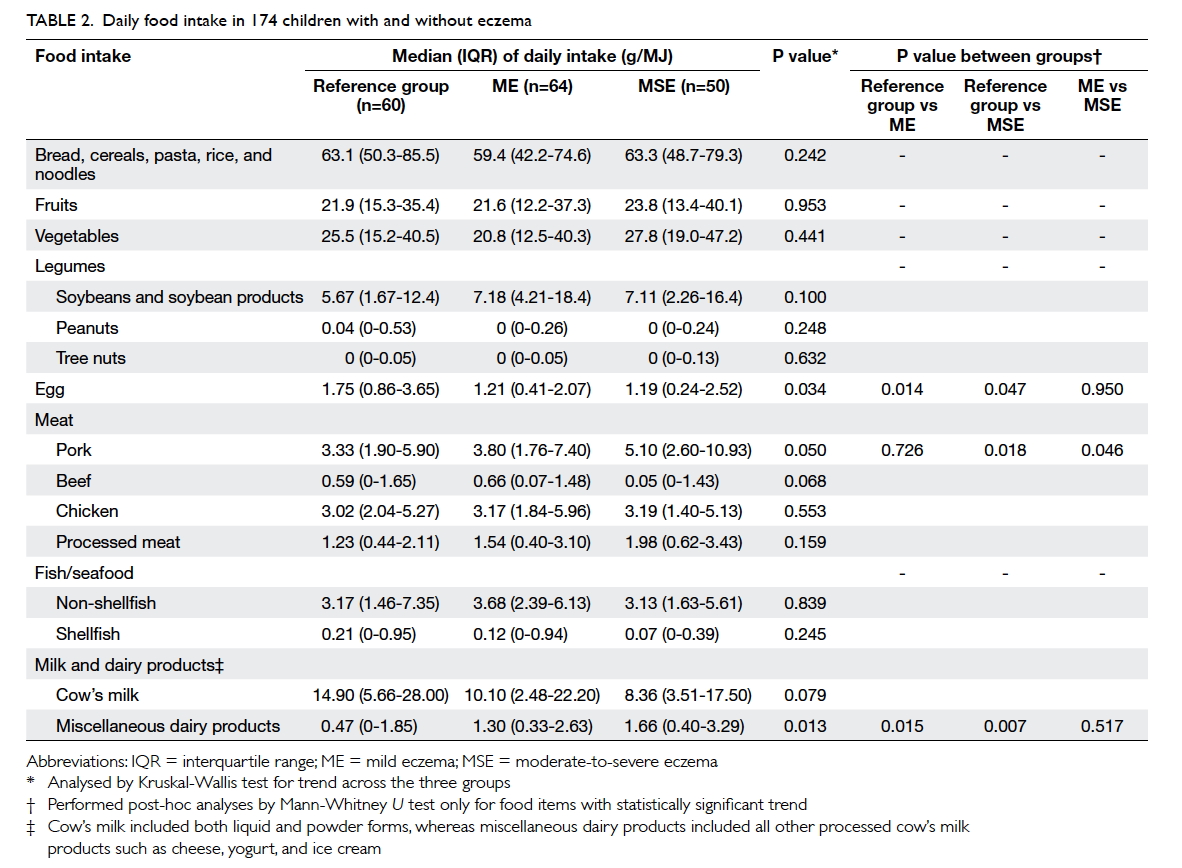

differ among children with eczema and those in the reference group. Table 2 describes the children’s daily

food intake adjusted for total energy as recorded by

FFQ. Males had a higher daily energy intake than

females (median [interquartile range]: 7570 [6267-9487] kJ vs 6736 [5438-8547] kJ; P=0.035), but intake

of any single food item or nutrient did not differ

when adjusted for daily energy intake. Multivariable

stepwise binary logistic regression analyses revealed that a

higher intake of soybeans and soybean products

as well as miscellaneous dairy products was

associated with an increased risk of eczema,

although statistically significant associations were

only found between the third tertile of soybean

intake and mild eczema, as well as between the second tertile and mild

eczema, and between the third tertile and moderate-to-severe

eczema for intake of miscellaneous dairy products.

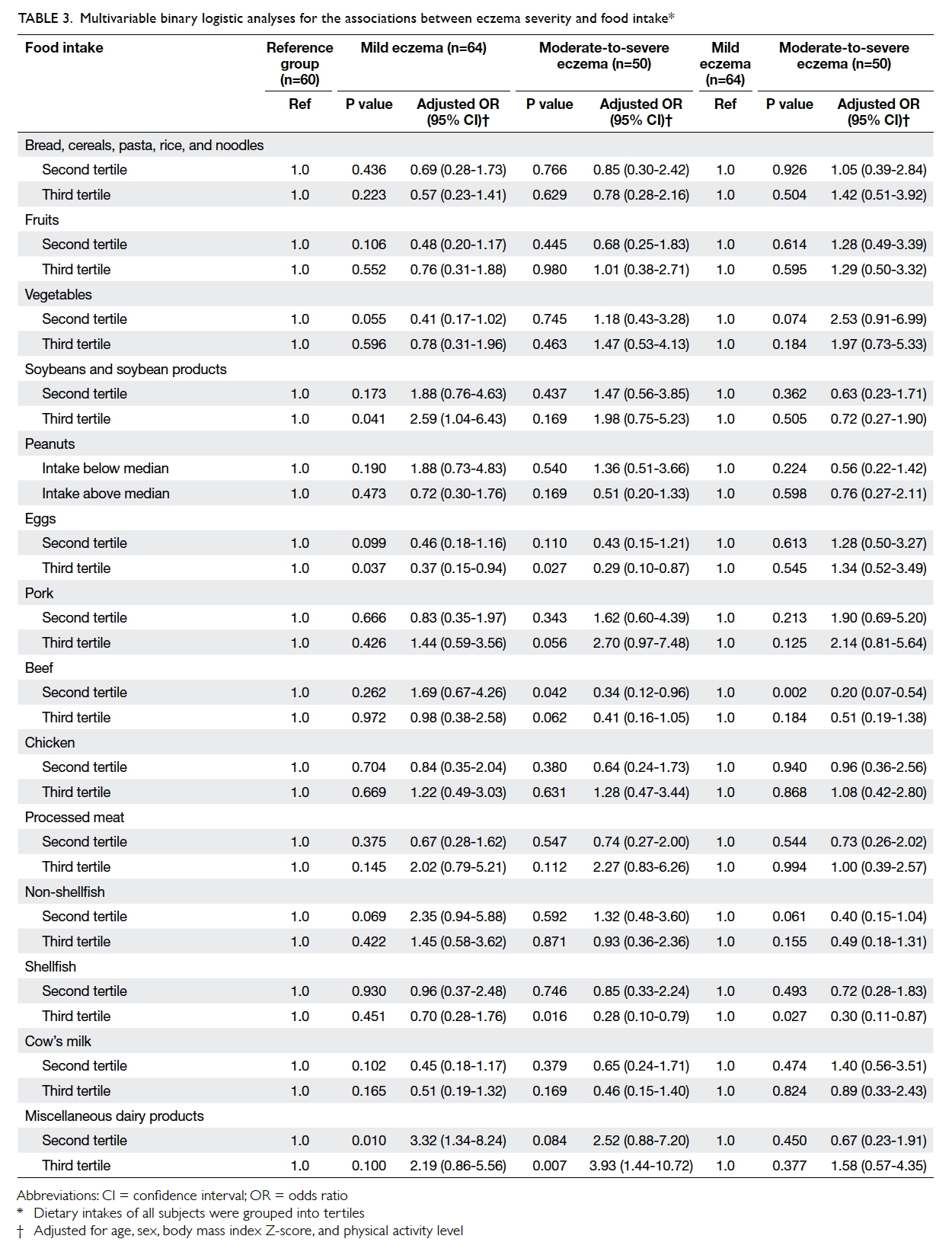

A higher consumption of eggs, beef, and shellfish

was associated with lower risk of eczema (Table 3).

Children with eczema and those in the reference

group consumed similar supplements of cod liver oil,

fish oil, vitamins, and calcium (P>0.9 for all; data not

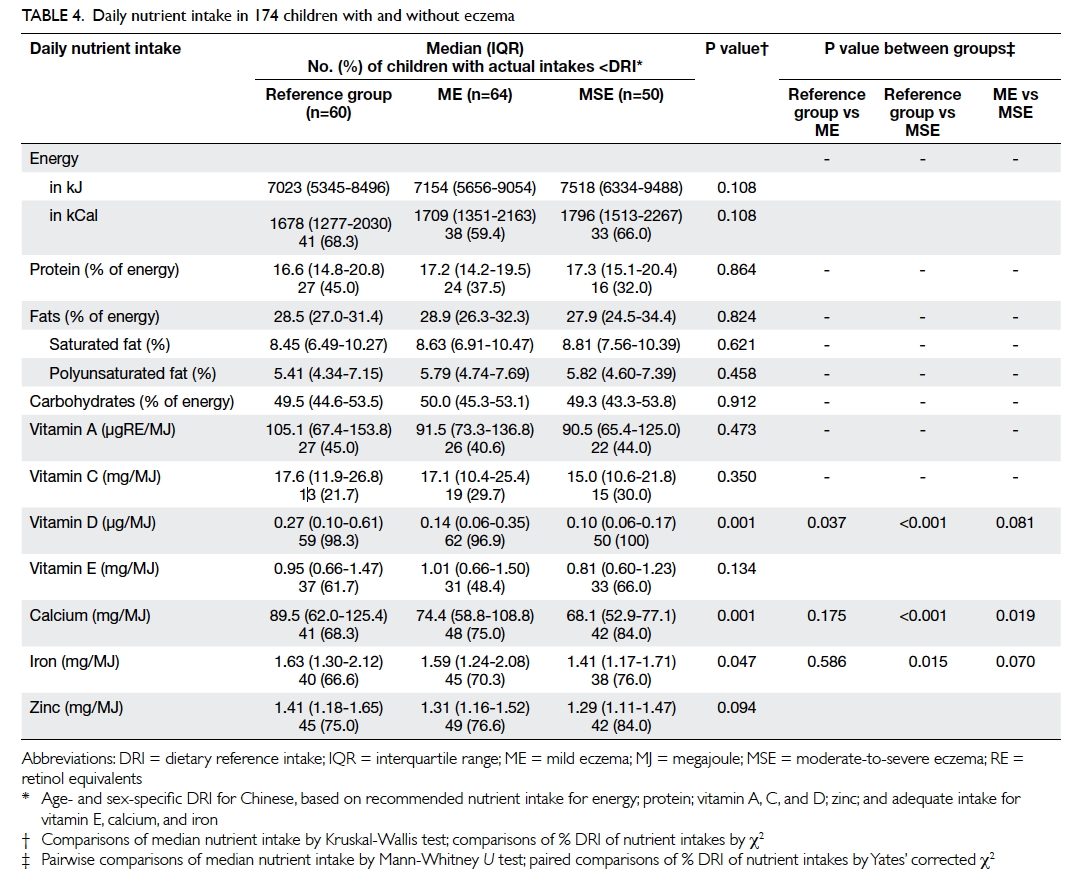

shown). Table 4 summarises their nutrient intake. Patients with moderate-to-severe eczema consumed

a lower amount of vitamin D, calcium, and iron when

compared with those with mild eczema and/or those

in the reference group. Children with the highest

tertile of intake for vitamin D (odds ratio [OR]=0.16;

95% confidence interval [CI] 0.05-0.48; P=0.001) and

calcium (OR=0.17; 95% CI, 0.06-0.51; P=0.002) had

a lower risk for moderate-to-severe eczema than

those with the lowest tertile when adjusted for age,

gender, BMI Z-score, and physical activity level as

covariates.

Table 3. Multivariable binary logistic analyses for the associations between eczema severity and food intake

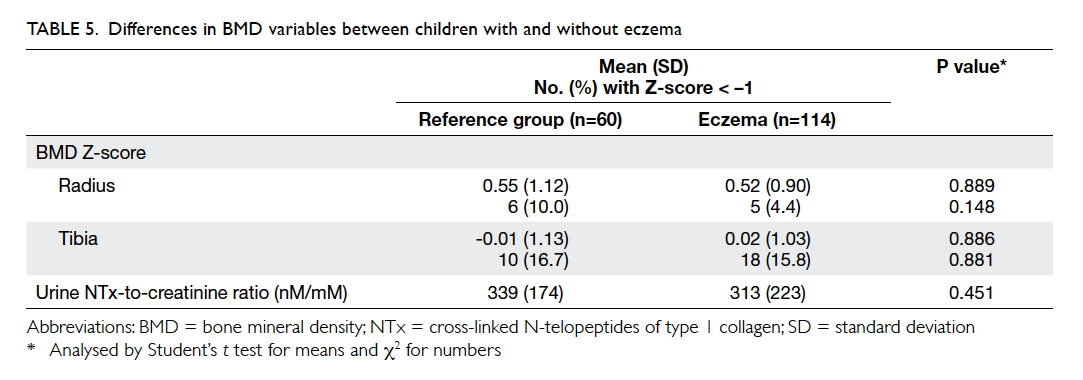

The mean BMD Z-score for children with

eczema and those in the reference group was 0.52

and 0.55 over the radius (P=0.889), and 0.02 and

–0.01 over the tibia (P=0.886) [Table 5]. The BMD

did not differ between children with mild and

moderate-to-severe eczema over these two regions

(P=0.296 and 0.661, respectively). The BMD Z-score

at the tibia correlated inversely with children’s

age (r = –0.282, P<0.001), but the Z-score at both

regions was independent of BMI Z-score. Age of

onset of eczema did not influence BMD Z-score at the radius (P=0.349) or tibia (P=0.240), nor was

it associated with physical activity level (P>0.1

for both). Urine NTx levels did not differ between

patients and reference subjects (P=0.451; Table 5), between reference subjects and those with mild or

moderate-to-severe eczema, or between those with

mild and moderate-to-severe eczema (P>0.3 for

all). This biomarker showed an inverse correlation with subject’s age (r = –0.569, P<0.001) but not BMI Z-score (r = –0.132, P=0.101) or BMD Z-score at

the radius (r = –0.133, P=0.097) or tibia (r = –0.135, P=0.093). Repeated analyses in eczema or reference

subject subgroups yielded similar results.

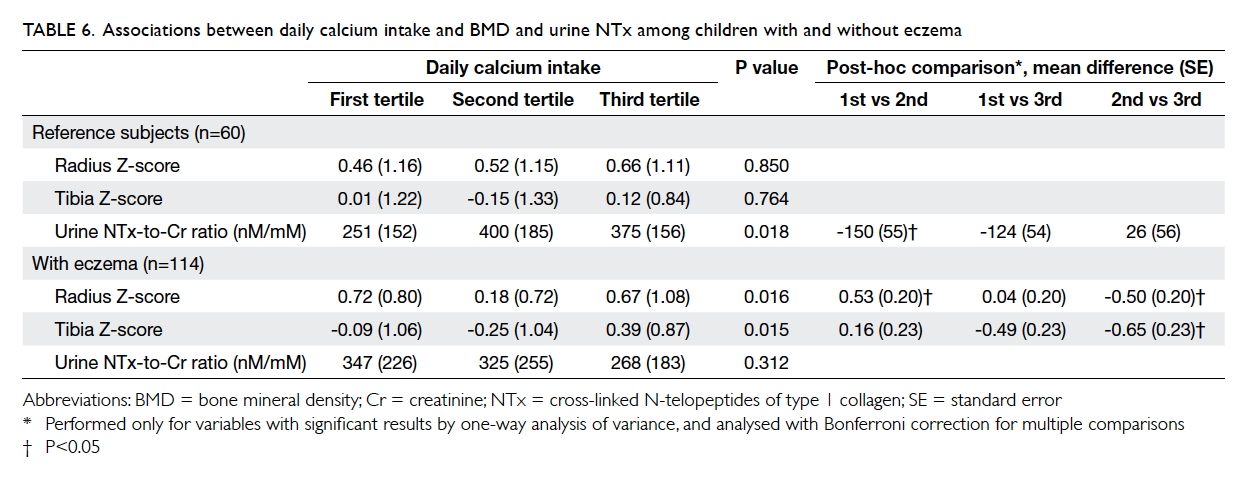

Regarding the possible effects of calcium

intake, the tertiles of daily intake were not associated

with BMD Z-score at either the radius or tibia among

reference subjects (Table 6). On the other hand,

patients at the second tertile of calcium intake had

a lower BMD Z-score at both the radius and tibia

than those at the first and third tertiles (P=0.016 and

0.015, respectively by one-way ANOVA). Patients

with the highest tertile of calcium intake had higher

BMD Z-score at the tibia.

Table 6. Associations between daily calcium intake and BMD and urine NTx among children with and without eczema

Discussion

This study is the first to report the effects of eczema

and dietary intake on BMD in Chinese children in

Hong Kong. Children with eczema had a higher

intake of soybeans and miscellaneous dairy products

but lower intake of eggs, beef, shellfish, vitamin D,

calcium, and iron than the reference group. Despite

these differences, children with eczema had similar

BMD Z-scores at the radius and tibia and urinary

NTx levels. We also observed a trend for patients

with the highest tertile of calcium intake to have a

higher BMD Z-score at the tibia.

Food allergy is commonly believed to be a

major cause of eczema in the Chinese culture. Werfel

and Breuer16 supported this by the finding that atopic

dermatitis could be exacerbated by certain foods in

more than 50% of affected children. Nonetheless,

reactions induced by classic foods such as hen’s eggs

and cow’s milk were less common in adolescents and

adults than in young children. Food allergy in eczema

may be immunoglobulin (Ig) E–mediated or non–IgE-mediated, thus food-induced eczema should be diagnosed only by thorough clinical history-taking

and diagnostic work-up. Because of a possible

co-existence of eczema and food allergy, dietary

restrictions form an integral component of eczema

management in children. A systematic review of 421

participants from nine randomised controlled trials

only suggested some benefit of an egg-free diet in

infants with suspected egg allergy who had positive

specific IgE to eggs. No benefit, however, could be

detected for the use of various exclusion diets in

unselected people with atopic eczema.17 Clinicians

should also bear in mind the dynamic nature of food

allergy, and that young children might outgrow such

allergies.

Eczema severity was associated with altered

dietary intake in our children. Of Hong Kong

children aged 2 to 7 years, 8% reported adverse food

reactions, with the six leading foods being shellfish,

eggs, peanuts, beef, cow’s milk, and tree nuts.2 Such

adverse reactions to multiple foods also led to worse

quality of life.18 In the EuroPrevall study, shrimp,

mango, milk, eggs, and peanuts were the foods most

commonly reported to cause allergy among primary

schoolchildren in Hong Kong.19 20 According to the

presence of allergen-specific IgE, however, milk and

egg sensitisation was identified in over 14% of these

subjects whereas that for all other foods including

shrimp and peanuts was less than 8%. In our

hospital-based patients, skin prick testing revealed

that shellfish, peanuts, nuts, and eggs were the most

common food allergens.21 In general, allergy to

milk, eggs, beef, and seafood is a common cultural

belief in Chinese families with children having eczema. Consistently, our patients with

moderate-to-severe eczema had a lower intake

of eggs, beef, and shellfish as well as vitamin D,

calcium, and iron (Tables 2 3

4). To compensate for such dietary restrictions,

they ingested more soybeans and soybean products,

as well as miscellaneous dairy products. These

alterations were consistent with our earlier findings

that dietary restrictions to avoid high calcium foods

such as cow’s milk were common among Hong

Kong children with eczema.3 22 Milk intake was also

negatively associated with eczema diagnosis among

Spanish primary schoolchildren.23

Dietary intake of vitamin D was very low in our

children, and virtually all (both cases and controls)

ingested a lower amount than the age- and sex-specific

dietary reference intake for the Chinese

population (Table 4). Our data also suggested an

inverse relationship between eczema severity and

vitamin D intake. These results echoed those of our

recent study in which low serum vitamin D level

was highly prevalent in both Hong Kong children

with eczema and non-allergic controls.24 Vitamin D

deficiency was associated with disease severity in our

eczema children. Our study found eczema severity

to be associated with several single-nucleotide

polymorphisms of vitamin D pathway genes.25 Besides

its role in bone metabolism, vitamin D3 exerted

pluripotent effects on both cutaneous adaptive (eg

T-cell activation and dendritic cell maturation) and

innate (eg expression of antimicrobial peptides)

immunity.26 27 Our data suggested low serum levels

of LL-37, the biologically active form of cathelicidin

involved in antimicrobial defence, in children with

eczema.28 Alterations in local vitamin D3 levels also

modulated skin barrier function.29 Most children in

Hong Kong, a subtropical region, had long school

hours on weekdays and swam mainly in indoor pools.

Thus, they are not expected to produce enough

vitamin D from sunlight exposure. Together with

our dietary data, we recommend that local children

increase their outdoor activities and dietary intake

of vitamin D.

Dietary intake of our children was recorded by

FFQ. This method has been used to assess habitual

intake over extended periods of time, ranging from the

past month to the past year, by asking respondents to

report frequency of consumption and often portion

size for a defined list of foods and beverages.30 This

allows for investigation of individual dietary pattern,

ranking of usual individual intake, and examination

of associations between frequency of consumption of

certain items and individual clinical conditions. Woo

et al9 developed an FFQ for the Hong Kong Chinese

population that was later adapted and validated in

local children and adolescents.11 12 13 18 Energy intake of

two thirds of our subjects was below the Chinese-specific

dietary reference intake (Table 4). Based

on our data, FFQ would overestimate the intake of

energy and macronutrients when compared with

a 3-day food record.11 Thus, both our patients and

controls had an inadequate nutritional intake.

Skeletal problems were common in children

with food allergy and eczema. The BMD in children

aged 8 to 17 years with CMA was markedly reduced for age, and calcium consumption was only one

quarter that recommended.5 Beta-crosslaps

concentration as a biomarker of bone turnover

was lower in CMA patients than in controls.6 Osteoporosis and osteopenia were detected in 4.8%

and 32.8% of 125 adults with moderate-to-severe

eczema, respectively.31 Low BMD in these patients

did not seem to respond to calcium and/or vitamin

D supplementation.32 Another small adult study

found similar BMD between subjects with eczema

and controls.33 In childhood eczema, patients with

severe disease treated with topical corticosteroids

and cyclosporin had much lower BMD as measured

by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) than

those prescribed topical corticosteroids alone.34 The BMD was similar between Dutch children

with moderate-to-severe eczema and the general

population.35 Overall, there are limited data

regarding BMD in childhood eczema. In this study,

children with eczema had similar sonographically

measured BMD at the radius and tibia and urinary

level of NTx when compared with controls (Table 5). Nonetheless, BMD Z-scores were lower among

patients in the second than third tertile of dietary

calcium intake (Table 6). We do not recommend

unjustified restriction of calcium-rich foods such as

cow’s milk and soybean in children with eczema.

This study has several limitations. First, we did

not record subjects’ outdoor activities or measure

their serum vitamin D level. Second, this study

assessed subjects’ dietary intake using a FFQ instead

of a 3-day food record. The FFQ is cheap and easy

to administer. Such FFQ with parental reporting was

also a reasonably valid way to collect dietary data

on children even in situations when parents do not

observe all meals and snacks eaten by their child.36 37 38 Third, because of its cross-sectional nature, this

study did not collect information about the duration

of food avoidance. Fourth, BMD of our children was

measured by ultrasound rather than DEXA; with the latter

being the gold standard for diagnosing osteoporosis.

There is substantial concern about radiation hazard

especially in children.39 This study adopted the

radiation-free technique of QUBS that was useful

in assessing BMD in children.40 Lastly, our patients

with moderate-to-severe eczema were nearly 2 years

older than the reference group although patients as

a whole group were of similar age (Table 1). Because

of the higher energy needs of older and bigger

children, we adjusted for subjects’ age and gender

in multivariable regression analyses and compared

their dietary intake with age- and gender-specific

dietary reference intakes.

Conclusion

Dietary restrictions are common among Chinese

children with eczema in Hong Kong. These patients

had a lower calcium, vitamin D, and iron intake. Despite this, childhood eczema was not associated

with diminished BMD. Nonetheless, a significant

association was detected between calcium intake

and BMD among these patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Direct Grants for Research

(2011.1.058 and 2013.2.033) of the Chinese

University of Hong Kong. We thank Yvonne YF Ho

and Patty PP Tse for helping with patient assessment

and data collection.

Declaration

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Leung DY, Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet

2003;361:151-60. Crossref

2. Leung TF, Yung E, Wong YS, Lam CW, Wong GW. Parent-reported

adverse food reactions in Hong Kong Chinese

pre-schoolers: epidemiology, clinical spectrum and risk

factors. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2009;20:339-46. Crossref

3. Hon KL, Leung TF, Kam WY, Lam MC, Fok TF, Ng PC.

Dietary restriction and supplementation in children with

atopic eczema. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;31:187-91. Crossref

4. Henderson RC, Hayes PR. Bone mineralization in children

and adolescents with a milk allergy. Bone Miner 1994;27:1-12. Crossref

5. Jensen VB, Jørgensen IM, Rasmussen KB, Mølgaard C,

Prahl P. Bone mineral status in children with cow milk

allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2004;15:562-5. Crossref

6. Hidvégi E, Arató A, Cserháti E, Horváth C, Szabó A, Szabó

A. Slight decrease in bone mineralization in cow milk-sensitive

children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2003;36:44-9. Crossref

7. Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic

dermatitis. Acta Derm (Stockh) 1980;92:44-7.

8. Hon KL, Leung TF, Wong Y, Fok TF. Lesson from

performing SCORADs in children with atopic dermatitis: subjective symptoms do not correlate well with disease

extent or intensity. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:728-30. Crossref

9.Woo J, Leung SS, Ho SC, Lam TH, Janus ED. A food

frequency questionnaire for use in the Chinese population

in Hong Kong: description and examination of validity.

Nutr Res 1997;17:1633-41. Crossref

10. Chan RS, Woo J, Chan DC, Cheung CS, Lo DH. Estimated

net endogenous acid production and intake of bone health-related

nutrients in Hong Kong Chinese adolescents. Eur J

Clin Nutr 2009;63:505-12. Crossref

11. Kwok FY, Ho YY, Chow CM, So CY, Leung TF. Assessment

of nutrient intakes of picky-eating Chinese preschoolers

using a modified food frequency questionnaire. World J

Pediatr 2013;9:58-63. Crossref

12. Yu CC, Sung RY, Hau KT, Lam PK, Nelson EA, So

RC. The effect of diet and strength training on obese

children’s physical self-concept. J Sports Med Phys Fitness

2008;48:76-82.

13. Bollen AM, Eyre DR. Bone resorption rates in children

monitored by the urinary assay of collagen type 1 cross-linked

peptides. Bone 1994;15:31-4. Crossref

14. Jones G, Boon P. Which bone mass measures discriminate

adolescents who have fractured from those who have not?

Osteoporosis Int 2008;19:251-5. Crossref

15. Christoforidis A, Printza N, Gkogka C, et al. Comparative

study of quantitative ultrasonography and dual-energy

X-ray absorptiometry for evaluating renal osteodystrophy

in children with chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner

Metab 2011;29:321-7. Crossref

16. Werfel T, Breuer K. Role of food allergy in atopic dermatitis.

Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;4:379-85. Crossref

17. Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary

exclusions for improving established atopic eczema in

adults and children: systematic review. Allergy 2009;64:258-64. Crossref

18. Leung TF, Yung E, Wong YS, Li CY, Wong GW. Quality-of-life assessment in Chinese families with food-allergic

children. Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39:890-6. Crossref

19. Wong GW, Mahesh PA, Ogorodova L, et al. The

EuroPrevall-INCO surveys on the prevalence of food

allergies in children from China, India and Russia: the

study methodology. Allergy 2010;65:385-90. Crossref

20. Wong GW, Ogorodova L, Mahesh PA, et al. Food allergy

in schoolchildren from China, Russia and India: the

EuroPrevall-INCO surveys. Allergy 2011;66 Suppl 94:27.

21. Hon KL, Wang SS, Wong WL, Poon WK, Mak KY, Leung

TF. Skin prick testing in atopic eczema: atopic to what and

at what age? World J Pediatr 2012;8:164-8. Crossref

22. Hon KL, Leung TF, Lam MC, et al. Eczema exacerbation

and food atopy beyond infancy: how should we advise

Chinese parents about dietary history, eczema severity and

skin prick testing? Adv Ther 2007;24:223-30.

23. Suárez-Varela MM, Alvarez LG, Kogan MD, et al. Diet

and prevalence of atopic eczema in 6 to 7-year-old

schoolchildren in Spain: ISAAC phase III. J Investig

Allergol Clin Immunol 2010;20:469-75.

24. Wang SS, Hon KL, Kong AP, Pong HN, Wong GW, Leung

TF. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with diagnosis and

severity of childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy

Immunol 2014;25:30-5. Crossref

25. Wang SS, Hon KL, Kong AP, et al. Eczema phenotypes

are associated with multiple vitamin D pathway genes in

Chinese children. Allergy 2014;69:118-24. Crossref

26. Bikle DD. What is new in vitamin D: 2006-2007. Curr Opin

Rheumatol 2007;19:383-8. Crossref

27. Schauber J, Dorschner RA, Yamasaki K, Brouha B,

Gallo RL. Control of the innate epithelial antimicrobial

response is cell-type specific and dependent on relevant

microenvironmental stimuli. Immunology 2006;118:509-19. Crossref

28. Leung TF, Ching KW, Kong AP, Wong GW, Chan JC, Hon

KL. Circulating LL-37 is a biomarker for eczema severity in

children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012;26:518-22. Crossref

29. Bikle DD, Chang S, Crumrine D, et al. Mice lacking 25OHD

1alpha-hydroxylase demonstrate decreased epidermal

differentiation and barrier function. J Steroid Biochem Mol

Biol 2004;89-90(1-5):347-53. Crossref

30. Thompson FE, Byers T. Dietary assessment resource

manual. J Nutr 1994;124(11 Suppl):2245S-2317S.

31. Haeck IM, Hamdy NA, Timmer-de Mik L, et al. Low bone

mineral density in adult patients with moderate to severe

atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2009;161:1248-54. Crossref

32. Haeck I, van Velsen S, de Bruin-Weller M, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C. Bone mineral density in patients with atopic dermatitis. Chem Immunol Allergy 2012;96:96-9.

Crossref

33. Aalto-Korte K, Turpeinen M. Bone mineral density

in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol

1997;136:172-5. Crossref

34. Pedreira CC, King E, Jones G, et al. Oral cyclosporin plus

topical corticosteroid therapy diminishes bone mass in

children with eczema. Pediatr Dermatol 2007;24:613-20. Crossref

35. van Velsen SG, Knol MJ, van Eijk RL, et al. Bone mineral

density in children with moderate to severe atopic

dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;63:824-31. Crossref

36. Andersen LF, Lande B, Trygg K, Hay G. Validation of a

semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire used

among 2-year-old Norwegian children. Public Health Nutr

2004;7:757-64. Crossref

37. Blum RE, Wei EK, Rockett HR, et al. Validation of a food frequency questionnaire in native American and

Caucasian children 1 to 5 years of age. Matern Child Health

J 1999;3:167-72. Crossref

38. Parrish LA, Marshall JA, Krebs NF, Rewers M, Norris JM.

Validation of a food frequency questionnaire in preschool

children. Epidemiology 2003;14:213-7. Crossref

39. Pearce MS, Salotti JA, Little MP, et al. Radiation exposure

from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of

leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study.

Lancet 2012;380:499-505. Crossref

40. Mainz JG, Sauner D, Malich A, et al. Cross-sectional

study on bone density-related sonographic parameters in

children with asthma: correlation to therapy with inhaled

corticosteroids and disease severity. J Bone Miner Metab

2008;26:485-92. Crossref