Hong Kong Med J 2017 Oct;23(5):454–61 | Epub 18 Apr 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164960

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Factors associated with multidisciplinary case

conference outcomes in children admitted to a

regional hospital in Hong Kong with suspected

child abuse: a retrospective case series with

internal comparison

WC Lo, MRCPCH, FHKAM (Paediatrics);

Genevieve PG Fung, MRCPCH, FHKAM (Paediatrics);

Patrick CH Cheung, FRCPCH, FHKAM (Paediatrics)

Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, United Christian

Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Patrick CH Cheung (cheungchp@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: In all cases of suspected child abuse,

accurate risk assessment is vital to guide further

management. This study examined the relationship

between risk factors in a risk assessment matrix and

child abuse case conference outcomes.

Methods: Records of all children hospitalised

at United Christian Hospital in Hong Kong for

suspected child abuse from January 2012 to

December 2014 were reviewed. Outcomes of the

hospital abuse work-up as concluded in the Multi-Disciplinary Case Conference were categorised

as ‘established’, ‘high risk’, or ‘not established’. All

cases of ‘established’ and ‘high risk’ were included

in the positive case conference outcome group and

all cases of ‘not established’ formed the comparison

group. On the other hand, using the Risk Assessment

Matrix developed by the California State University,

Fresno in 1990, each case was allotted a matrix

score of low, intermediate, or high risk in each of

15 matrix domains, and an aggregate matrix score

was derived. The effect of individual matrix domain

on case conference outcome was analysed. Receiver

operating characteristic curve analysis was used to

examine the relationship between case conference

outcome and aggregate matrix score.

Results: In this study, 265 children suspected of being

abused were included, with 198 in the positive case

conference outcome group and 67 in the comparison

group. Three matrix domains (severity and frequency

of abuse, location of injuries, and strength of family

support systems) were significantly associated with

case conference outcome. An aggregate cut-off score

of 23 yielded a sensitivity of 91.4% and specificity of

38.2% in relation to outcome of abuse categorisation.

Conclusions: Risk assessment should be performed

when handling suspected child abuse cases. A

high aggregate score should arouse suspicion in all

disciplines managing child abuse cases.

New knowledge added by this study

- The Risk Assessment Matrix provides an objective measure of the risk of abuse and can effectively aid communication between professionals and guide junior colleagues in decision making.

- Using the Risk Assessment Matrix, an aggregate matrix score of ≥23 serves to alert health care professionals to the degree of risk involved, and to gauge appropriate follow-up response.

- Professionals should perform risk assessment and document the results in a systematic manner.

- Results of risk assessment should be considered in Multi-Disciplinary Case Conference on Protection of Child with Suspected Abuse to guide decision making and formulation of a welfare plan.

- As this study used a risk assessment matrix from overseas, further studies should be performed to develop an assessment tool for local use.

Introduction

Child abuse is damaging to children’s physical health,

emotional health, learning, and development.1 2 3

From time to time, there are media reports of

severe child abuse that has required admission to

an intensive care unit or resulted in death. A recent

recommendation in March 2016 by a coroner

following an inquest into the death of a 5-year-old

child was the need for a careful risk assessment when

handling cases of suspected child abuse.4

In Hong Kong, approximately 1000 children

are admitted to hospitals each year for suspected

child abuse. The abuse may be physical, sexual, or

psychological; involve neglect; or consist of multiple

abuses.5 Management of these children calls for multidisciplinary

involvement. A Multi-Disciplinary Case

Conference on Protection of Child with Suspected

Abuse (MDCC) is recommended as stated in the

Procedural Guide for Handling Child Abuse Cases

of the Social Welfare Department of the Hong Kong

Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) Government.6 Whether

a case is abuse or not is concluded by the MDCC

that involves doctors, nurses, psychologists, medical

social workers, social workers from Social Welfare

Department or non-governmental organisations,

school personnel, and the police.

The Procedural Guide6 is under review.

New procedures introduced in its recent revision

have been implemented since December 2015.

In Chapter 11 of the MDCC, a new standing

conference agenda item on risk assessment was

introduced and mandated. Managing professionals

are advised to perform risk assessment on abuse.

This risk assessment is vital when considering the

nature of child abuse and the care of the child and

family. Several assessment instruments or models

to assess harm have been reviewed.7 8 Each has its own strengths and weaknesses. The Risk Assessment

Matrix (developed by the California State University,

Fresno, in 19909) has been quoted in the Procedural

Guide for Handling Child Abuse Cases of the Social

Welfare Department, HKSAR Government.6 The Risk Assessment

Matrix has not been previously systematically used

in MDCC in Hong Kong. Since 2015, the Social

Welfare Department of HKSAR Government has recommended

that systematic risk assessment be performed in

MDCC for all cases. This study was performed to

examine the relationship between risk factors in the

Risk Assessment Matrix and MDCC outcome.

Methods

United Christian Hospital is a tertiary referral

hospital that serves a paediatric population of around

110 000 in the Kwun Tong district in Hong Kong.10

Children with suspected child abuse are admitted

to hospitals in Hong Kong for multidisciplinary

management that includes work-ups by paediatrics,

psychology, psychiatry, social work disciplines as

well as community social work agencies, schools,

and the police. An MDCC is held within 10 working

days in which all involved disciplines participate

to conclude the nature of abuse (case conference

outcome) and the subsequent welfare plan for the

child and family. This was a retrospective case series

with internal comparison to investigate the risk

factors and case conference outcome of children

admitted with suspected abuse from January 2012 to

December 2014. Ethics approval for the study was

obtained from the Kowloon Central/Kowloon East

Clusters Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital

Authority.

Subjects

All cases of suspected child abuse (coded per the

ICD-9 system) within the study period were identified

from discharge diagnosis using the Hospital

Authority Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting

System electronic database. The medical records, the

MDCC investigation reports by various disciplines,

and the MDCC meeting minutes were retrieved and

retrospectively reviewed. Cases were categorised as

‘established’ (E), ‘high risk’ (HR), or ‘not established’

(NE) for child abuse, as determined in the MDCC.

All E and HR cases were included in the positive case

conference outcome group, and all NE cases were

included in the comparison group. Cases with no

MDCC were excluded from analysis.

In this study, the ratio of E+HR:NE cases was

198:67 (ie 3:1). Using this sample size, and assuming

an odds ratio (OR) of >2 would be considered

significant, the chance of detecting a significant

difference at the 5% level was 65%.

Measures

Baseline demographic data, type of abuse, abusers,

and relevant risk factors were collected for all cases.

The Risk Assessment Matrix (developed by the

California State University, Fresno, in 19909) adopted

by the Social Welfare Department in their Procedural

Guide for Handling Child Abuse Cases6 was used to

associate risk factors with final categorisation. The

full risk assessment form is shown in the Appendix.

This assessment categorises risk factors for child

abuse into 15 matrix domains to assess the child,

parent/caretaker, and family situation. For each

matrix domain, the level of risk is classified as ‘low’

(MLR), ‘intermediate’ (MIR), or ‘high’ (MHR). The

matrix was discussed in detail among the authors

before starting the study, and details of classification

clarified. Classification was performed by one author

only, thereby eliminating the possibility of inter-rater

variability. Cases that were difficult to classify were

discussed among authors and decisions were made

by consensus. Association between risk categories in

the matrix and final categorisation was reviewed by

looking at the MIR + MHR category in relation to

case conference outcomes. To further quantify the

matrix, an empirical scoring system was devised,

with 1 point for MLR, 2 points for MIR, and 3 points

for MHR in each of the 15 matrix domains. For each

assessed case, an aggregate score of 15 to 45 was

possible.

Appendix. Risk Assessment Matrix in the Procedural Guide for Handling Child Abuse Cases of the Social

Welfare Department, Hong Kong SAR Government6

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical

Package for the Social Sciences (Windows version

23.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States). Categorical data

were compared using the Chi squared test or Fisher’s

exact test (for cells <5), and OR with 95% confidence

interval (CI) were calculated. Continuous variables

were compared using the independent t test, Mann-Whitney U test, or one-way analysis of variance (for

multiple groups). Multivariate logistic regression

(stepwise strategy) was used to determine the effect

of individual matrix domains on case conference

outcome. The independent variables used in logistic

regression analysis were the matrices that showed

a significant association in the initial univariate

analysis. To study the association between matrix

scores and final categorisation, a receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted with

sensitivity and specificity calculations. A two-sided

P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

It was hypothesised that (1) risk factors for

child abuse are present in a higher proportion in

the E/HR cases compared with the NE cases, and

(2) the aggregate risk profile score is higher in the

positive case conference outcome group than in the

comparison group.

Results

We identified 272 cases during the study period.

After review of diagnosis and case notes, seven cases

were excluded. For all excluded cases, no MDCC was

held because they were judged to be inappropriate

referrals for assessment of child abuse after initial

careful assessment. Therefore, 265 cases were

included in the study.

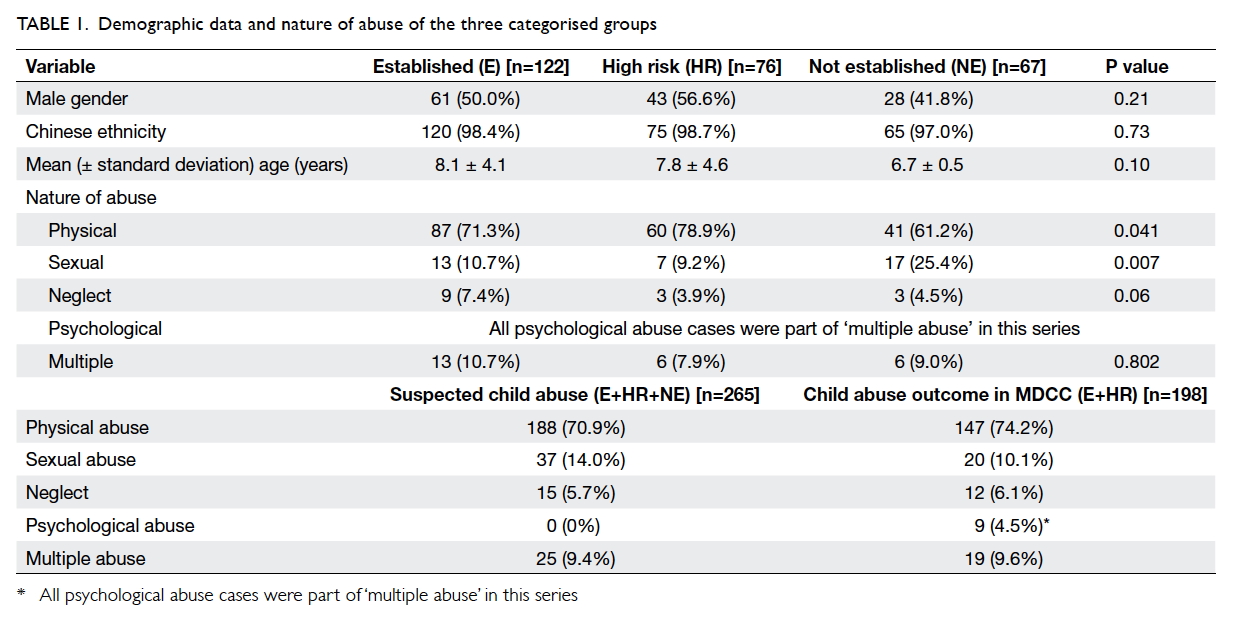

After multidisciplinary work-up, the case

conference conclusion by MDCC showed that 46.0%

(122/265) of cases were categorised as E, 28.7%

(76/265) as HR, and 25.3% (67/265) as NE. There were

ultimately 198 cases in the positive case conference

outcome group (E+HR) and 67 in the comparison

group (NE). Physical abuse cases accounted for

70.9% (188/265), and the percentages of sexual abuse,

neglect, and multiple abuse (≥2 abuse categories)

were 14.0%, 5.7%, and 9.4%, respectively. There were

nine cases of psychological abuse (3 E and 6 HR),

but they were also confirmed to be associated with

other types of abuse (eg ‘physical + psychological’

or ‘neglect + psychological’). There were no cases of

‘isolated psychological abuse’ in this series (Table 1).

In most cases the abuser was identified as

the mother (45.5%, 90/198), followed by the father

(27.3%, 54/198), domestic helper (4.0%, 8/198),

parent’s co-habitant (2.0%, 4/198), grandfather

(1.5%, 3/198) or grandmother (1.5%, 3/198), internet

friend (1.5%, 3/198), or stepfather (1.0%, 2/198) or

stepmother (1.0%, 2/198). In 4.5% of cases, multiple

abusers were identified, and in 5.1%, the abuser

could not be identified. Other abusers accounted for

5.1% and included tutorial class teachers, mother’s

friends, classmate or hostel peer, siblings, boyfriend,

godmother, and other relatives.

Comparison of baseline demographic data

showed no significant difference in gender, ethnicity,

or mean age at presentation among the E, HR, and

NE groups (Table 1). When the nature of abuse was

compared, there was a higher percentage of physical

abuse in the E and HR groups, but no significant difference in

the percentage of psychological, multiple abuse, or

neglect between groups. A significant difference

was identified for sexual abuse, however, with the

highest percentage in the NE group (10.7% vs 9.2%

vs 25.4%; P=0.007). Several features were observed

in this subgroup of sexual abuse as follows. Multidisciplinary

investigations and physical examination

were frequently not revealing. Children were

often young and thus unable to speak with non-specific

vulval or perineal redness or symptomatic

vulvovaginitis. Child custody disputes, maternal

emotional problems, or a child being cared for by

multiple individuals were common features.

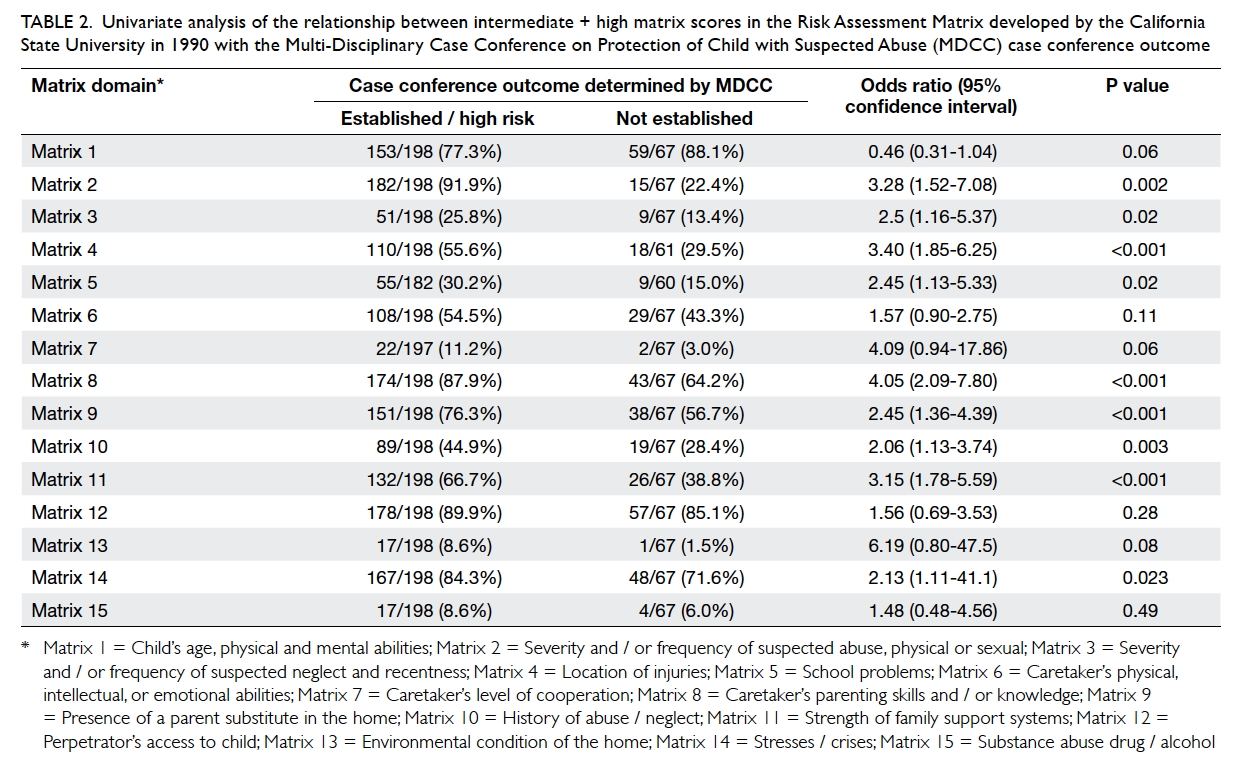

Univariate analysis for the MIR + MHR

categories in each matrix domain showed significant

correlation between MIR + MHR in the positive case

conference outcome group (E + HR) for nine matrix

domains, including Matrix 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, and

14 (Table 2).

Table 2. Univariate analysis of the relationship between intermediate + high matrix scores in the Risk Assessment Matrix developed by the California State University in 1990 with the Multi-Disciplinary Case Conference on Protection of Child with Suspected Abuse (MDCC) case conference outcome

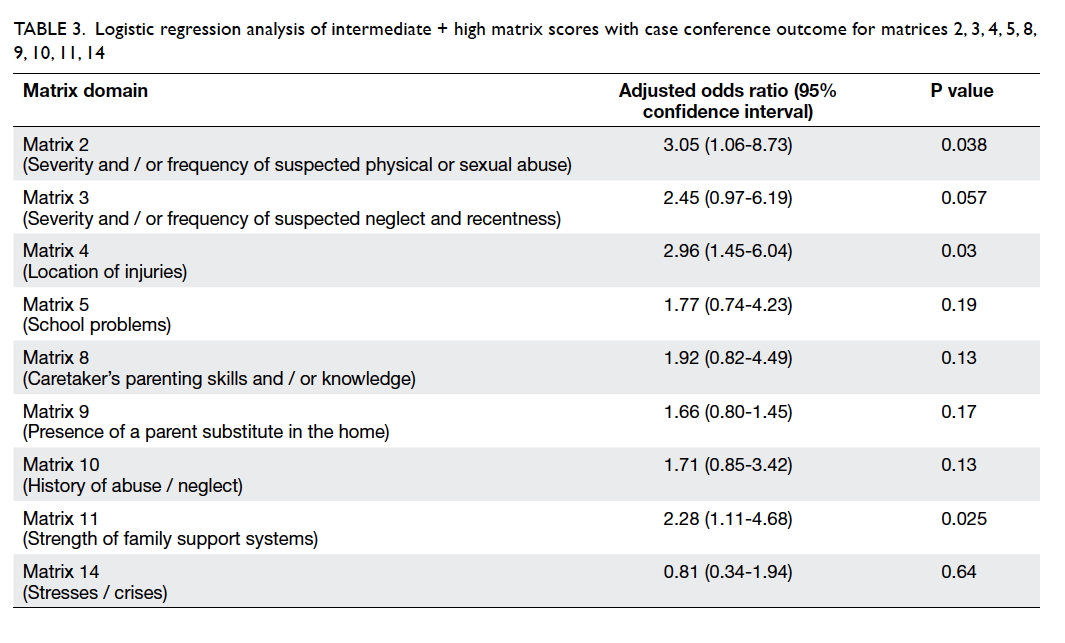

Logistic regression for these nine matrix

domains showed significant correlation for Matrix 2,

severity and/or frequency of abuse; Matrix 4, location

of injuries; and Matrix 11, strength of family support

systems (Table 3).

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of intermediate + high matrix scores with case conference outcome for Matrixes 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14

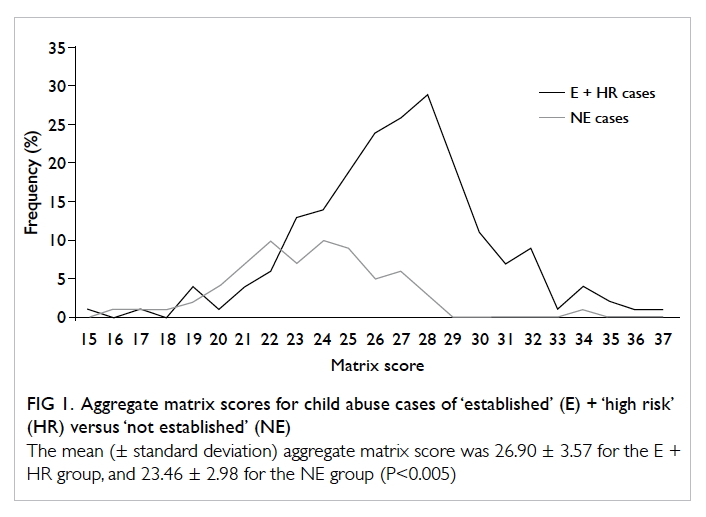

Using the devised scoring system of 1 point

for MLR, 2 for MIR and 3 for MHR, an aggregate

matrix score was calculated for each patient, with

a minimum possible score of 15, and maximum

possible score of 45. The aggregate matrix scores for

both the positive case conference outcome group

(E+HR) and comparison group (NE) followed a

normal distribution (Fig 1). The mean aggregate

matrix score was significantly different between the

two groups with a higher mean score in the positive case

conference outcome group (26.90 ± 3.57 vs 23.46 ±

2.98; P<0.005).

Figure 1. Aggregate matrix scores for child abuse cases of ‘established’ + ‘high risk’ versus ‘not established’

The mean (± standard deviation) aggregate matrix score was 26.90 ± 3.57 for the E + HR group, and 23.46 ± 2.98 for the NE group (P<0.005)

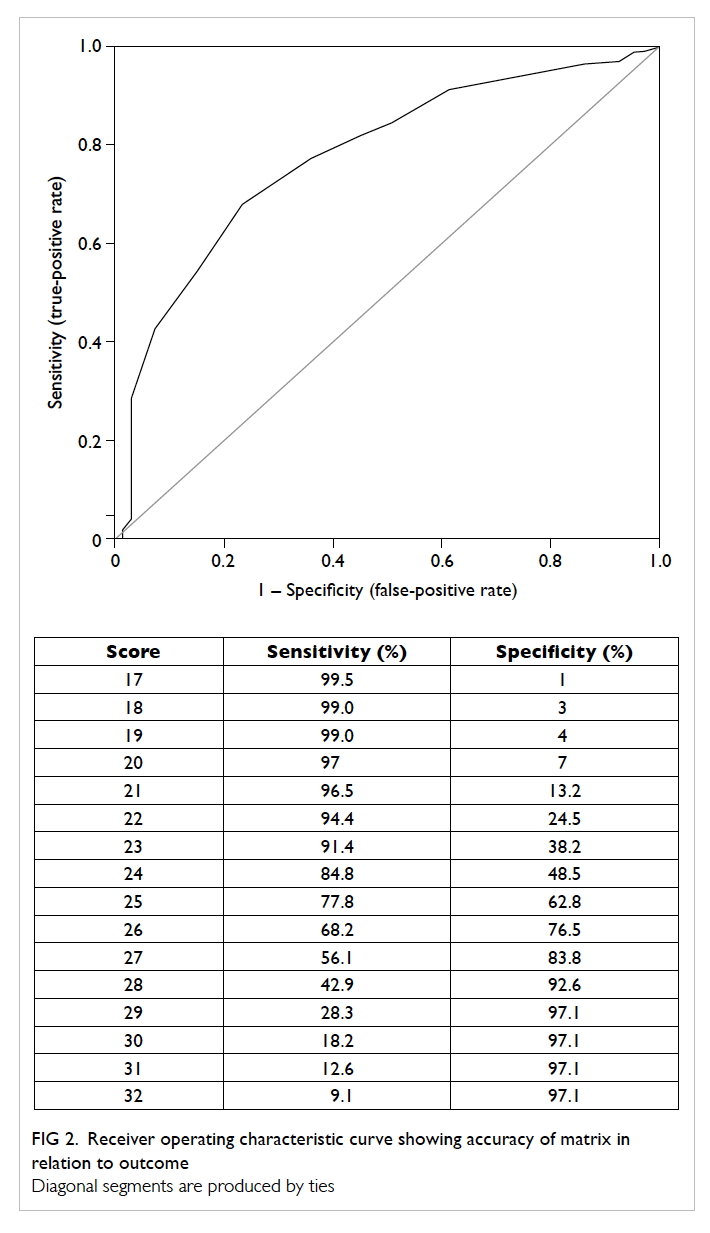

To estimate the association of the matrix

scores with the risk of child abuse, an ROC curve was

plotted using aggregate matrix score against E + HR

cases (Fig 2). The area under the ROC curve was 0.78

(95% CI, 0.72-0.84), indicating good discrimination.

Figure 2. Receiver operating characteristic curve showing accuracy of matrix in relation to outcome

Diagonal segments are produced by ties

The sensitivity and specificity of different

aggregate matrix scores are shown in Figure 2.

For this study, a matrix score that yielded a high

sensitivity was preferred, in order to avoid missing

cases of abuse. A cut-off aggregate matrix score of 23

would yield a sensitivity of 91.4% and specificity of

38.2% in relation to E + HR; a mean aggregate matrix

score of 24 would yield a sensitivity of 84.8% and

specificity of 48.5%.

Discussion

Risk assessment is a critical process by which to

assess the level of risk to a child suspected of being

abused. Instruments used in risk assessment organise

factors systematically to help describe the safety of

such a child. These factors include characteristics

of the reported abuse, the child, the caretakers, the

family, and the environment of the child.7 8 11 12 13 Such assessment helps case analysis and decision making,

and provides an important framework for case

planning and subsequent service delivery.

Since December 2015, risk assessment in

MDCC has been mandated in the Procedural Guide

for Handling Child Abuse Cases of the Social Welfare

Department, HKSAR Government.6 In this Procedural Guide, a

risk assessment instrument (Risk Assessment Matrix

developed by the California State University, Fresno,

in 19909) was referred to and takes the form of a

matrix that facilitates assessment by professionals

of the level of risk for various abuse factors. This

study examined the relationship between child abuse

risk factors and MDCC outcome using this Risk

Assessment Matrix.

There was no significant difference in

demographic data among the three groups (E, HR,

and NE; Table 1). A statistical difference in the

presence of child sexual abuse was found between

the positive case conference outcome group (E+HR)

and the comparison group (NE), with a higher

proportion of children in the comparison group

affected. Future study to analyse characteristic

features of the NE group would aid understanding of

sexual abuse cases that present to hospitals in Hong

Kong.

There was no ‘isolated’ psychological abuse in

this series. All psychological abuses occurred with

multiple abuses. Psychological abuse is easily missed

as there is often no physical sign to arouse suspicion.

All cases in this series came to light during the

work-up for other forms of abuse. In 2015, there

were only seven cases of psychological abuse among

the 874 newly reported child abuse cases in Hong

Kong.14 Psychological abuse is underdiagnosed

in our locality and this calls for sensitivity among

professionals when handling abuse cases.

On characteristics of abusers, parents,

especially mothers, were the most prevalent abusers.

This finding is consistent with previous studies.12 15 16 17

Certain parental characteristics have been identified

as important risk factors for child abuse, for

example, parental low mood, marital conflict

precipitating emotional problems, parental low

education or economic status, poor social support, and

parenting stress due to handling a child’s disruptive

behaviour.12 15 16 17 18

Logistic regression analysis revealed three

factors that were significant for established or high

risk of child abuse (E or HR): (1) Matrix 2: severity

and/or frequency of suspected physical or sexual

abuse, (2) Matrix 4: location of injuries, and (3)

Matrix 11: strength of family support systems (Table 3).

Matrix 2: Severity and/or frequency of

suspected physical or sexual abuse

History of child abuse, and severity and frequency

of abuse are known risk factors for recurrence of

abuse. Child abuse victims may not experience

abuse as a one-off event. Further, there was evidence

of escalation in abuse severity in recurrent abuse

victims.19 20 Corporal punishment is commonly adopted by Chinese parents as a method of

child discipline, and severe physical punishment

warranting medical attention or hospital admission

has been reported in 3% to 9% of children.15 18 Only 1% of abuse cases are reported and managed.15

Contributing factors for underreporting include

cultural acceptance of corporal punishment, low

public awareness, and lack of victim support during

the disclosure process.

Matrix 4: Location of injuries

Head and neck injury was regarded as severe

physical injury compared with injury to limbs and

corporal body parts.18 A review of literature revealed

that abusive bruises are found predominantly on

the head and neck, especially on the ear, neck, and

cheeks—all sites that are unlikely to be affected by

accidental injury. Areas such as the forearms, upper

limbs, and adjoining area of the trunk, or outside

thigh may indicate ‘defensive bruising’ when the

child tries to avoid being hit.21 Head and neck injuries

such as abusive head injury, contusions of the head

or neck, are well known to cause deleterious effects,

even mortality.22

Matrix 11: Strength of family support systems

Families with poor social support, social isolation,

and geographical isolation are known to be at

increased risk and severity of child abuse.16 17 19 22

Social isolation was more common among single

parents or immigrants.15 Both a low level of real

and perceived social support has been shown to be

potential risks for child maltreatment.15 16 17 On the

contrary, social support is a protective factor for child

abuse.23 Perceived social support has been reported

to moderate parents’ own experience of abuse and

the potential risk of abuse of their own children.16

Parental support can be offered by child care or

foster care services, targeted support programmes

for families at risk or young families with a newborn,

parental counselling service, and extra support to

vulnerable children with special needs.23

Six other matrix domains were significantly

related with case conference outcome in univariate

analysis but not in logistic regression analysis

(Tables 2 and 3). They were Matrix 3, 5, 8, 9, 10 and

14. Another six risk factors were not statistically

related to case conference outcome; these included

Matrix 1, 6, 7, 12, 13, and 15. All risk factors in these

domains have been shown in previous studies to be

related to child abuse.11 12 13 15 16 17 Possible explanations

for the absence of a significant relationship between risk

factors in these 12 domains and case conference

outcome in logistic regression analysis include

an aggregate effect of risk factors that may not be

significant on their own but factor co-occurrence is

contributory. Other possible explanations include

presence of mitigating factors such as a protective

relative, a child already in supportive placement, the

presence of legal enforcement or a child under a care

order, or because of a small subgroup number within

individual risk factors.

For the aggregate effect of risk factors, an

ROC curve was plotted using aggregate matrix

score against case conference outcome (Figs 1 and 2). As the Risk Assessment Matrix is used as a risk

assessment tool for child abuse, it is vital that it

detects most abuse cases. We chose a score that yields

a high sensitivity and high positive predictive value

whilst accepting a lower specificity. Using a score of

23 (sensitivity 91.4%, positive predictive value 0.85,

specificity 38.2%) or 24 (sensitivity 84.8%, positive

predictive value 0.8, specificity 48.5%) ensured that

most child abuse cases were identified. The high

sensitivity indicates that most cases of E and HR

child abuse would be correctly identified in MDCC.

A welfare plan could then be formulated to protect

the child and help the family to prevent further abuse.

The low specificity, however, meant that a relatively

large number of ‘non–child abuse’ cases could be

subject to unnecessary investigations, leading to

an increased workload for all parties involved and

stress to the family. Nonetheless, a highly sensitive

cut-off is important to avoid a false-negative result

and missing a genuine case of child abuse that may

have serious or even fatal consequences.

In a recent death inquest, the importance

of risk assessment was strongly emphasised by

the coroner.4 The aggregate matrix score offers a

reference to alert professionals in handling suspected

child abuse cases. A matrix score of >23 calls for

increased vigilance and careful planning, especially

in situations such as making a decision about hospital

discharge before MDCC. Further, because job

placements of disciplines such as social work or legal

enforcement are often rotation-based rather than

long-term specialist-focused, where experience and

professional judgement are important cumulative

assets, a systematic risk assessment using objective

scores serves as a practical tool and as a warning

mechanism in abuse handling, especially for the

less-experienced professionals.

This study has some limitations. In Hong Kong,

reported cases of child abuse are only the tip of the

iceberg.15 Subjects in this study were hospitalised

children in a regional hospital setting, and results

of this retrospective study cannot be generalised

to the territory. The Fresno model has previously

been considered a model with low validity and inter-rater

reliability.7 As with other consensus-based

risk assessment instruments, the rating of risks in

the matrix domains will invariably involve a degree

of subjectivity.7 8 This was minimised in this study by our further defining situations with objective

measures. For example, for domain 10, intermediate

risk was defined as a reported case but subsequently

concluded as not an established child abuse case

to be followed up by a school social worker or

Integrated Family Services Centre. High risk was

defined as a history of established child abuse in

the past. For domain 14, insufficient income was

defined as receipt of Comprehensive Social Security

Assistance. Recent change in marital or relationship

status was defined as parents in divorce proceedings,

child in a custody dispute, or active marital discord

causing emotional outbursts. It is hoped that with

training and further refining of the matrix contents

to fit the local culture, the inter-rater reliability and

reproducibility of the Fresno tool can be improved.

Nevertheless other risk assessment instruments can

also be examined for local use.

The social structure and culture of a society

keeps changing. Up-to-date studies are required

to examine child abuse risk profiles. A prospective

multicentre study is valuable for development of a

local risk assessment tool. With the implementation

of changes in the Procedural Guide for Handling

Child Abuse Cases,6 a systematic risk assessment

will facilitate investigative procedures and improve

safeguarding of vulnerable children.

Conclusions

Three matrix risk factors in the Risk Assessment

Matrix were significantly associated with child

abuse—severity and/or frequency of suspected physical

or sexual abuse (Matrix 2), location of injuries

(Matrix 4), and strength of family support systems

(Matrix 11). Further, other risk factors in the matrix,

although not significant in logistic regression

analysis, showed good association with child abuse

case conference outcomes in univariate analysis. A

risk assessment framework facilitates case analysis,

and guides decision making and case planning

such that appropriate service delivery is ensured.

Using the devised scoring system of the referenced

Risk Assessment Matrix, an aggregate matrix score

of ≥23 should arouse suspicion of all professionals

when managing child abuse.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos

T. The long-term health consequences of child physical

abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review

and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001349. Crossref

2. Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E,

Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment

in high-income countries. Lancet 2009;373:68-81. Crossref

3. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of

childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the

leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood

Experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245-58. Crossref

4. Siu J. Hong Kong government urged to amend guide on

handling child abuse in coroner’s case involving death of

boy who probably ingested Ice. South China Morning Post

2016 Mar 16.

5. Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System, Hong Kong

Hospital Authority. Accessed 16 Nov 2016.

6. Social Welfare Department of the Hong Kong SAR Government. Procedural Guide for Handling Child Abuse Cases 2015. Available

from: http://www.swd.gov.hk/en/index/site_pubsvc/page_family/sub_fcwprocedure/id_1447/. Accessed 16 Nov

2016.

7. D’Andrade A, Austin MJ, Benton A. Risk and safety

assessment in child welfare: instrument comparisons. J

Evid Based Soc Work 2008;5:31-56. Crossref

8. Barlow J, Fisher JD, Jones D. Systematic review of models

of analysing significant harm. Research report DFE-RR199.

London: Department for Education; 2012.

9. California risk assessment curriculum for child welfare

services, CSU Fresno, Child Welfare Training Project.

Sponsored and funded by the California State Department

of Social Service; 1990.

10. Census and Statistics Department. Population and

household statistics analysed by District Council district.

Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR Government; 2016.

11. Milner JS. Assessing physical child abuse risk: the child

abuse potential inventory. Clin Psychol Rev 1994;14:547-83. Crossref

12. Begle AM, Dumas JE, Hanson RF. Predicting child abuse

potential: an empirical investigation of two theoretical

frameworks. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2010;39:208-19. Crossref

13. Chan YC, Lam GL, Chun PK, So MT. Confirmatory factor

analysis of the Child Abuse Potential Inventory: results

based on a sample of Chinese mothers in Hong Kong.

Child Abuse Negl 2006;30:1005-16. Crossref

14. Social Welfare Department. Child Protection Registry

statistical report 2015. Hong Kong: Hong Kong SAR

Government; 2015.

15. Study on child abuse and spouse battering. Report on

findings of household survey. Hong Kong SAR: Department of Social Work

and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong;

2005.

16. Yoon AS. The role of social support in relation to parenting

stress and risk of child maltreatment among Asian

American immigrant parents [dissertation]. US: University

of Pennsylvania; 2013.

17. Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Salzinger S. A longitudinal

analysis of risk factors for child maltreatment: findings

of a 17-year prospective study of officially recorded and

self-reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl

1998;22:1065-78. Crossref

18. Leung PW, Wong WC, Chen WQ, Tang CS. Prevalence and

determinants of child maltreatment among high school

students in Southern China: a large scale school based

survey. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2008;2:27. Crossref

19. Thackeray J, Minneci PC, Cooper JN, Groner JI, Deans

KJ. Predictors of increasing injury severity across

suspected recurrent episodes of non-accidental trauma: a

retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr 2016;16:8. Crossref

20. Deans KJ, Thackeray J, Groner JI, Cooper JN, Minneci PC.

Risk factors for recurrent injuries in victims of suspected

non-accidental trauma: a retrospective cohort study. BMC

Pediatr 2014;14:217. Crossref

21. Maguire S. Which injuries may indicate child abuse? Arch

Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2010;95:170-7. Crossref

22. Kemp AM. Abusive head trauma: recognition and the

essential investigation. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed

2011;96:202-8. Crossref

23. Chan KL. Study on child-friendly families: Immunity from

domestic violence. Hong Kong SAR: Department of Social Work and Social

Administration, The University of Hong Kong; 2008.