DOI: 10.12809/hkmj166110

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE

The feeding paradox in advanced dementia: a

local perspective

James KH Luk, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

Felix HW Chan, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Elsie Hui,

FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)2; CY Tse, FHKCCM, FHKAM

(Medicine)3

1 Department

of Medicine and Geriatrics, Fung Yiu King Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Department

of Medicine and Geriatrics, Shatin Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

3 Hospital Authority Clinical Ethics Committee, Hospital

Authority, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr James KH

Luk (lukkh@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Feeding problems are common in older people with

advanced dementia. When eating difficulties arise tube feeding is often

initiated, unless there is a valid advance directive that refuses enteral

feeding. Tube feeding has many pitfalls and complications. To date, no

benefits in terms of survival, nutrition, or prevention of aspiration

pneumonia have been demonstrated. Careful hand feeding is an alternative to

tube feeding with advanced dementia. In Hong Kong, the Hospital Authority

has established clear ethical guidelines for careful hand feeding.

Notwithstanding, there are many practical issues locally if tube feeding is

not used in older patients with advanced dementia. Training of doctors,

nurses, and other members of the health care team is vital to the

promulgation of careful hand feeding. Support from the government and

Hospital Authority policy, health care staff training, public education, and

promotion of advance care planning and advance directive are essential to

reduce the reliance on tube feeding in advanced dementia.

Introduction

Hong Kong is facing an unparalleled challenge of rapid

population ageing.1 This demographic change results in an

impending need for end-of-life care among older people with advanced

dementia.2 One of the natural stages of the dementia

disease process is eating problems with poor appetite and swallowing

difficulty, leading to malnutrition, weight loss, and aspiration pneumonia

(AP).3 4 Unless there is a valid advance

directive (AD) refusing enteral feeding, family members and the health care

team often feel compelled to initiate tube feeding. This leads to a very

high prevalence of tube feeding in elderly with advanced dementia,

especially those living in residential care homes for the elderly (RCHEs).5

6

Pitfalls of tube feeding

There are many reasons for placing a feeding tube in

patients with advanced dementia. Medical, social, cultural, economic,

ethical, psychological, and medicolegal factors all play a part in the

decision.7 Many older patients are commenced on tube

feeding when they are dysphagic or are feeding inadequately. Probably due to

inadequate information about the pitfalls of tube feeding, risk of AP and

survival are the most frequently cited reasons by health care teams to

insert a feeding tube.8 To date, however, evidence has

proven that tube feeding does not prevent AP.9 On the

contrary, AP might be increased by the use of enteral feeding.10

Placement of a nasogastric tube weakens the lower oesophageal sphincter and

reduces the efficiency of the valve that prevents gastric reflux into the

upper digestive tract.11 The use of tube feeding without

oral feeding also leads to neglect of oral hygiene, resulting in bacterial

colonisation and an increased risk of AP. Enteral feeding is unable to

improve serum albumin, body weight, or lean muscle mass.12

The use of a feeding tube causes patient discomfort, increased use of

restraints, and consequent greater likelihood of pressure sore development.13

14 Studies showed that RCHE residents with feeding tubes

are frequently transferred to an emergency department for tube complications

such as blockage and dislodgement.15 To date, studies

have not shown survival benefits in older people with tube feeding.16

In a local study of 312 advanced cognitively impaired RCHE residents, 164

(53%) were being tube fed.6 The 1-year mortality rate was

34% and enteral feeding was cited as an important risk factor for 1-year

mortality (odds ratio=2.0; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.4; P=0.008).6

Careful hand feeding as an alternative

Careful hand feeding (CHF) has been advocated as an

alternative for older people with advanced dementia and eating problems.17

In CHF, the carer makes use of feeding techniques such as frequent

reminders to swallow, multiple swallows, encouraging gentle coughs after each

swallow, limiting bolus size to less than one teaspoon, and judicious use of

thickeners. The carer observes the patient for choking and pocketing of food

in the mouth. The carer focuses on the older person during the entire

feeding process and avoids distraction. The older person is placed in an

upright position during the meal. Moistening foods with water or sauces, or

alternating food with appropriate liquid consistency may help swallowing,

for example, in patients with a dry mouth.

In the 2014 position statement on feeding

tubes in advanced dementia published by the

American Geriatrics Society, feeding tubes are not

recommended.18 It emphasises that CHF should be

offered as it is at least as good as tube feeding for

the outcomes of death, AP, functional status, and

comfort.19 20 Older patients with dementia can still

form a relationship with their carer. Actions by the

carer can influence food intake of an older person

with dementia and include touching, kissing,

hugging, and responding to non-verbal cues.21

Caregivers can provide patients frequent reminders

to swallow, perform multiple swallows, make

gentle small coughs between feeds, and assume

an appropriate posture to reduce the risk of AP. A

pleasant quiet environment with less distraction is

desirable during the whole feeding process.

Reasons for a high prevalence of

tube feeding in advanced dementia

in Hong Kong

Family factors

Tube feeding is prevalent in Hong Kong among

older patients with advanced dementia for multiple

reasons. Family members may think that they cannot

allow the demented relative to starve. This may be

affected by the Chinese culture that emphasises

eating and avoidance of hunger at all costs. To

achieve this, there seems to be little other choice.

Physicians may be too optimistic and inform family

members that the tube can be removed if the patient

regains the ability to eat normally.22 The chance of

stopping tube feeding, however, is lower than 20%

in all indications for tube feeding.23 Family members

may insist on aggressive measures at all costs, despite

the futility.

Health care team factors

The current medical culture in Hong Kong is

predominantly biomedical, with life preservation

the overwhelming principle.24 Physicians may

recommend tube feeding in older patients with

advanced dementia because they believe clinical

outcomes can be thereby improved.25 Many

physicians are under pressure from family members

when discussing tube feeding.26 The health care team may be unfamiliar with the current literature about

the pitfalls of tube feeding and may not realise that

there is also an option of CHF. The health care team

may also fear legal consequences if patients with

advanced dementia are not fed with a feeding tube.

Lack of an advance directive and

advance care planning

Advance care planning (ACP) is a process of

communication among patients, their family, and

important others about the care they wish to receive

if they are unable to make decisions.27 Often one of

the discussions relates to the decision to start tube

feeding in the presence of severe eating problems.

One outcome of ACP is an expressed wish that is not

legally binding. Another option is for the patient to

sign an AD, a formal tool that respects the autonomy

of patients and in which any decision must be

adhered to by the health care team.28 In Hong Kong,

life-sustaining treatment, including tube feeding, can

be withheld if there is a valid AD when the patient is

in an irreversible coma, persistent vegetative state,

terminal illnesses, or other end-stage irreversible

life-limiting condition.29 Nonetheless until recently

ACP and AD have been seldomly discussed in

Hong Kong.30 When a patient without an AD is

unconscious due to an advanced irreversible illness,

the decision to withhold or withdraw tube feeding

is made by consensus of the health care team and

family members according to the best interests of

the patient, taking into account any prior wish or

treatment preference. Without knowing the exact

wishes of the patient, many health care teams and

family members are compelled to start tube feeding.

Practical issues in not using tube

feeding

In Hong Kong, there are practical issues associated with not using a feeding tube. Hand feeding is time-consuming.

In the hospital environment, because of

staff shortages, it is difficult to provide quality CHF

to all patients with advanced dementia having eating

problems. If an older patient is feeding poorly, it is

difficult to discharge them from hospital, especially

if they are returning to a RCHE. The environment

can also affect feeding.31 Medical wards in Hong

Kong public hospitals are often elderly unfriendly,

crowded, noisy, and without privacy. In addition,

nurses may be reluctant to hand feed the advanced

dementia patient with dysphagia after assessment by

a speech therapist. Without strong hospital policy

support, nurses understandably are concerned about

medicolegal consequences should the dysphagic

elderly patient aspirate following CHF. Hence,

not uncommonly, they will ask relatives who have

‘refused’ tube feeding of an elderly dysphagic older

to feed them. Family members who are unable to

come to the hospital 2 or 3 times a day will have

little choice but to alter their decision and agree to

tube feeding. In RCHEs, manpower issues and the

crowded environment are barriers to quality feeding

of those with dementia. Older RCHE residents who

are offered CHF but are feeding poorly will soon

become dehydrated, especially in summer. Staff in

RCHEs will soon bring their older residents back

to the emergency ward/department if they cannot

eat or are eating poorly, leading to a ‘revolving door’ phenomenon. Alternative ways of hydration,

including hypodermoclysis (subcutaneous fluid

infusion), are not practised in RCHEs in Hong

Kong.32 Not many family doctors are equipped

with the knowledge or have the time to take care of

advanced dementia cases with feeding problems in

RCHEs. Many medications need to be taken orally

and administration via an enteral tube may appear to

be the only alternative in dysphagic patients.

Hospital Authority guidelines on

life-sustaining treatment in the

terminally ill

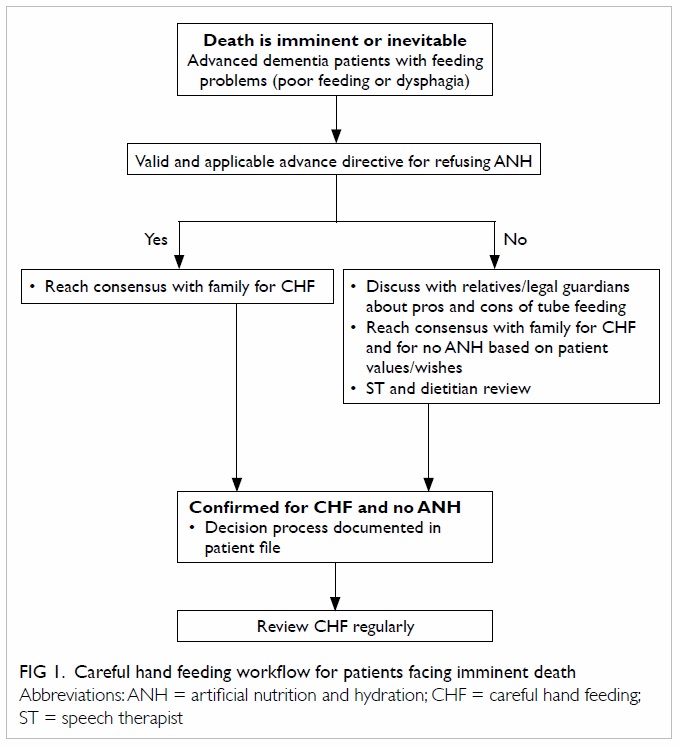

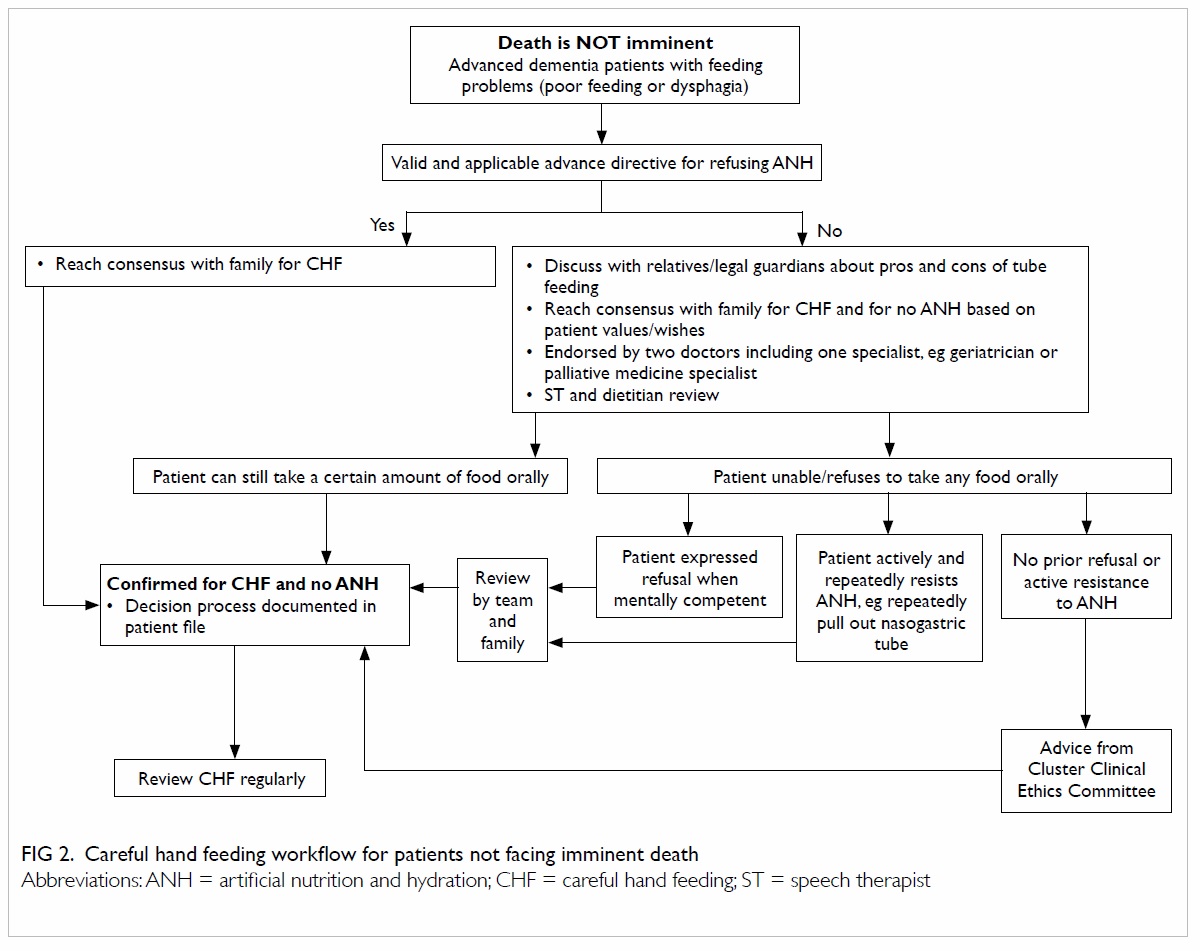

Artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) refers

specifically to those techniques for providing

nutrition or hydration which are used to bypass

the swallowing process. They include the use

of nasogastric tubes, percutaneous endoscopic

gastrostomy, intravenous or subcutaneous fluid, and

parenteral nutrition. In September 2015, the Hospital

Authority guidelines on life-sustaining treatment

in the terminally ill was updated. Among other

key end-of-life care issues, the guidelines provide

a clear picture of CHF and ANH from the ethical

perspective.33 It states that when death is imminent

(death is expected within a few hours or days) and

inevitable in a mentally incompetent patient without

a valid AD, it is acceptable to withhold or withdraw

ANH. This follows the same principles that apply to

other life-sustaining treatments. Notwithstanding,

if a patient is in or near the end stage of a disease

or condition and is mentally incompetent, and

death is not imminent, the balance of benefits and

burdens of ANH may become unclear. The guideline

states that if the patient does not have a valid AD

refusing ANH, the consideration of withholding or

withdrawing ANH requires additional safeguards.

There must be consensus within the health care

team and with the family (if any) that a decision to

withhold or withdraw ANH is in the best interests

of the patient, taking into account their prior wishes

and values. The health care team must include at

least two doctors, one of whom must be a specialist

in a relevant field, eg geriatrician or palliative care

specialist. In addition, if the patient is unable to

swallow, the health care team should seek advice

from the ‘cluster clinical ethics committee’, before

making a decision to withhold or withdraw ANH,

unless before losing capacity, the patient has clearly

expressed a wish to refuse ANH (as reported clearly

by family members or documented in medical

notes when the patient was still competent) or the

patient actively and repeatedly resists ANH such as

repeatedly pulling out a nasogastric tube. Based on

the principles stipulated in the Hospital Authority

guidelines,33

Figures 1 and

2 were drawn showing

the flowcharts when death is imminent/inevitable

and when death is not imminent, respectively.

The way forward for feeding

patients with advanced dementia

in Hong Kong

There is no definitive solution for feeding problems

in older patients with advanced dementia. In the

absence of a valid AD, patient management should be

individualised, and the decision for tube feeding or

CHF should be shared between the health care team

and family members, based on the patient’s previously

expressed wishes and best interests. The health care

team should accept and respect the family’s choice

of CHF instead of tube feeding. Experienced nurses

and doctors should be responsible for discussing

the pros and cons of tube feeding with the family to

achieve a consensus. Clear hospital guidelines and

protocols should facilitate CHF and effect a cultural

change.34 Staff sentiments and medicolegal concerns

should be addressed. Clear Hospital Authority or

hospital policy to support CHF will help alleviate the

concerns of nursing staff. Training of doctors, nurses,

and other members of the health care team is vital to

the promulgation of CHF. There is an urgent need to

enhance the environment of public hospital wards so

that they are more elderly friendly. Training of RCHE

staff and the staff ratio are important factors that will

determine the success of CHF in the community of

Hong Kong. Without a well-prepared staff, patients

on CHF will soon be put on enteral feeding. The

Social Welfare Department can ensure it is part of

the licensing requirement to have end-of-life care

that includes CHF in most, if not all, RCHEs. More

palliative care training should be given to primary

doctors who look after older people with advanced

dementia.35 Recently, all medical students at the

University of Hong Kong have been seconded to

RCHEs to learn about community geriatrics as part

of their undergraduate training. They have first-hand

experience, under the guidance of geriatricians,

of how the elderly with advanced dementia are

cared for in RCHEs. More education about feeding

issues in dementia should be offered to the public.

Furthermore, ACP and AD should be promoted in

Hong Kong so that patients can elect a particular

mode of feeding while they are mentally capable.36 At

the time of writing this article, the Hong Kong SAR

Government is exploring the realisation of enduring

power of attorney for health care decision, allowing

mentally incapacitated older people to express their

wishes through a chosen advocate.37 It is hoped that

the decision to accept enteral feeding or not can be

included in the scope of the power of attorney.

References

1. Hong Kong population projections 2012-2041. Census

and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR Government;

2012.

2. Luk JK, Liu A, Ng WC, Lui B, Beh P, Chan FH. End-of-life

care: towards a more dignified dying process in residential

care homes for the elderly. Hong Kong Med J 2010;16:235-6.

3. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Keily DK, et al. The clinical course of

advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529-38.

Crossref

4. Hoffer LJ. Tube feeding in advanced dementia: the

metabolic perspective. BMJ 2006;333:1214-5.

Crossref

5. Luk JK, Chan FH, Pau MM, Yu C. Outreach geriatrics

service to private old age homes in Hong Kong West

Cluster. J Hong Kong Geriatr Soc 2002;11:5-11.

6. Luk JK, Chan WK, Ng WC, et al. Mortality and health

services utilization among older people with advanced

cognitive impairment living in residential care homes.

Hong Kong Med J 2013;19:518-24.

7. Luk JK, Chan DK. Preventing aspiration pneumonia in

older people: do we have the “know-how”? Hong Kong

Med J 2014;20:421-7.

8. Li I. Feeding tubes in patients with severe dementia. Am

Fam Physician 2002;65:1605-10, 1515.

9. Finucane TE, Christmas C, Travis K. Tube feeding in

patients with advanced dementia: a review of the evidence.

JAMA 1999;282:1365-70.

Crossref

10. Vergis EN, Brennen C, Wagener M, Muder RR. Pneumonia

in long-term care: a prospective case-control study of

risk factors and impact on survival. Arch Intern Med

2001;161:2378-81.

Crossref

11. Gomes GF, Pisani JC, Macedo ED, Campos AC. The

nasogastric feeding tube as a risk factor for aspiration and

aspiration pneumonia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care

2003;6:327-33.

Crossref

12. Ciocon JO, Silverstone FA, Graver LM, Foley CJ. Tube

feedings in elderly patients. Indications, benefits, and

complications. Arch Intern Med 1988;148:429-33.

Crossref

13. Kuo S, Rhodes RL, Mitchell SL, Mor V, Teno JM. Natural

history of feeding-tube use in nursing home residents with

advanced dementia. J Am Dir Assoc 2009;10:264-70.

Crossref

14. Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Kuo SK, et al. Decision-making and

outcome of feeding tube insertion: a five-state study. J Am

Geriatr Soc 2011;59:881-6.

Crossref

15. Odom SR, Barone JE, Docimo S, Bull SM, Jorgensson D.

Emergency departments visits by demented patients with

malfunctioning feeding tubes. Surg Endosc 2003;17:651-3.

Crossref

16. Mitchell SL, Tetroe JM. Survival after percutaneous

endoscopic gastrostomy placement in older persons. J

Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000;55:M735-9.

Crossref

17. DiBartolo MC. Careful hand feeding: a reasonable

alternative to PEG tube placement in individuals with

dementia. J Gerontol Nurs 2006;32:25-33.

18. American Geriatrics Society Ethics Committee and

Clinical Practice and Models of Care Committee. American

Geriatrics Society feeding tubes in advanced dementia

position statement. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1590-3.

Crossref

19. Hanson LC, Ersek M, Gilliam R, Carey TS. Oral feeding

options for people with dementia: a systematic review. J

Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:463-72.

Crossref

20. Hanson LC. Tube feeding versus assisted oral feeding

for persons with dementia: using evidence to support

decision-making. Ann Longterm Care 2013;21:36-9.

21. Lange-Alberts ME, Shott S. Nutritional intake. Use of

touch and verbal cuing. J Gerontol Nurs 1994;20:36-40.

Crossref

22. Carey TS, Hanson L, Garrett JM, et al. Expectations and

outcomes of gastric feeding tubes. Am J Med 2006;119:527.e11-6.

23. Wolfsen HC, Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, Patterson DJ, Botoman

VA, Ryan JA. Long-term survival in patients undergoing

percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and jejunostomy.

Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:1120-2.

24. Pang MC, Volicer L, Chung PM, Chung YM, Leung WK,

White P. Comparing the ethical challenges of forgoing

tube feeding in American and Hong Kong patients with

advanced dementia. J Nutr Health Aging 2007;11:495-501.

25. Shega JW, Hougham GW, Stocking CB, Cox-Hayley D,

Sachs GA. Barriers to limiting the practice of feeding tube

placement in advanced dementia. J Palliat Med 2003;6:885-93.

Crossref

26. Solomon MZ, O’Donnell L, Jennings B, et al. Decisions

near the end of life: professional views on life-sustaining

treatments. Am J Public Health 1993;83:14-23.

Crossref

27. Teno JM, Nelson HL, Lynn J. Advance care planning.

Priorities for ethical and empirical research. Hasting Cent

Rep 1994;24:S32-6.

Crossref

28. Chu LW, Luk JK, Hui E, et al. Advance directive and end-of-life care preferences among Chinese nursing home

residents in Hong Kong. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011;12:143-52.

Crossref

29. Guideline for HA clinicians on advance directives in adults

(2014). Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2014.

30. Tse CY. Reflections on the development of advance

directives in Hong Kong. Asian Bioethics Rev 2016;8:211-23. Crossref

31. Amella EJ. Factors influencing the proportion of food

consumed by nursing home residents with dementia. J Am

Geriatr Soc 1999;47:879-85.

Crossref

32. Luk KH, Chan HW, Chu LW. Is hypodermoclysis suitable

for frail Chinese elderly? Asian J Gerontol Geriatr

2008;3:49-50.

33. HA guidelines on life-sustaining treatment in the

terminally ill 2015. Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2015.

34. Palecek EJ, Teno JM, Casarett DJ, Hanson LC, Rhodes RL,

Mitchell SL. Comfort feeding only: a proposal to bring

clarity to decision-making regarding difficulty with eating

for persons with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc

2010;58:580-4.

Crossref

35. Hong TC, Lam TP, Chao VK. Barriers for primary care

physicians in providing palliative care service in Hong

Kong—qualitative study. Hong Kong Pract 2010;32:3-9.

36. Luk JK, Liu A, Ng WC, Beh P, Chan FH. End of life care in

Hong Kong. Asian J Gerontol Geriatr 2011;6:103-6.

37. The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong Report.

Enduring powers of attorney: personal care. July 2011.

Available from: http://www.hkreform.gov.hk/en/docs/repa2_e.pdf. Accessed 29 Apr 2017.