DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144416

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Three cases of early-stage localised Lyme disease

Mahizer Yaldiz, MD1;

Teoman Erdem, MD1;

Fatma H Dilek, MD2

1 Department of Dermatology, Sakarya University Training and Research Hospital, Sakarya 54010, Turkey

2 Department of Pathology, Sakarya University Training and Research Hospital, Sakarya 54010, Turkey

Corresponding author: Dr Mahizer Yaldiz (drmahizer@gmail.com)

Case reports

Case 1

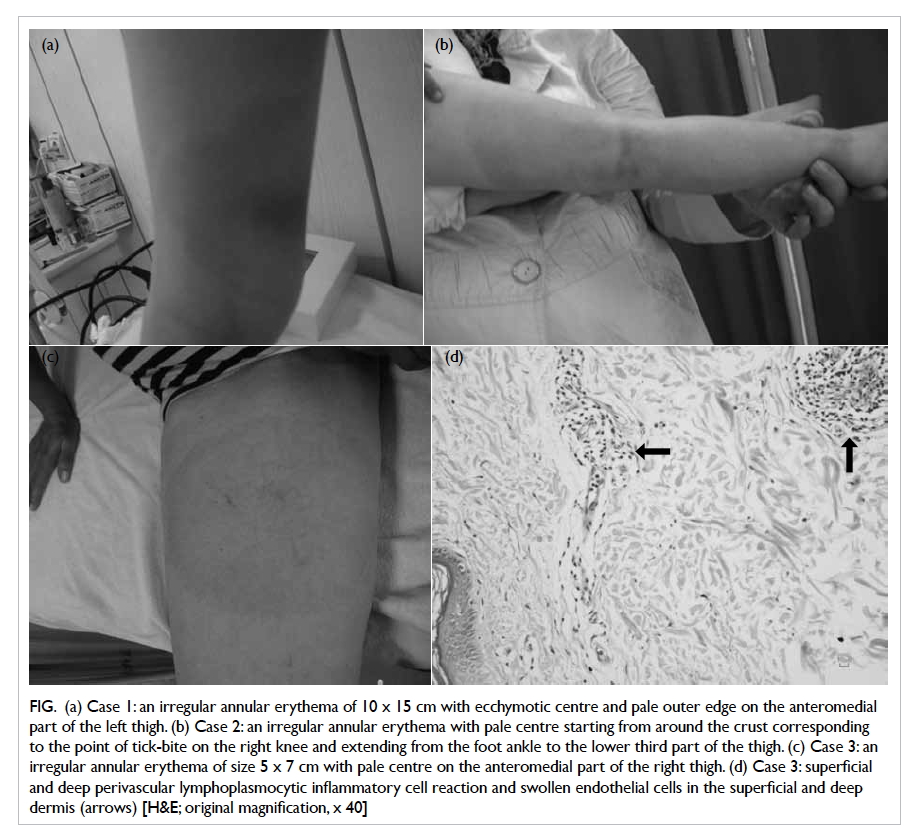

A 6-year-old girl was referred to our hospital in July

2010 with a red patch on one leg. The red patch

had appeared 15 days after a tick-bite and become

increasingly large within the last 1.5 months.

Dermatological examination revealed an irregular

annular erythema of 10 x 15 cm, with ecchymotic

centre and pale outer edge on the anteromedial part

of her left thigh (Fig a). Systemic examination as well as complete blood picture and liver and renal

function tests were normal. In view of the history of

tick-bite and prediagnosis of erythema chronicum

migrans (ECM), Borrelia burgdorferi serology was

requested and confirmed positive immunoglobulin

(Ig) M to B burgdorferi. A diagnosis of Lyme disease

was considered and treatment was started with

amoxicillin and clavulanic acid at a paediatric dose

of 50 mg/kg/day. After 15 days, the patient showed

clinical improvement and at 6-month follow-up

there were no systemic findings.

Figure. (a) Case 1: an irregular annular erythema of 10 x 15 cm with ecchymotic centre and pale outer edge on the anteromedial part of the left thigh. (b) Case 2: an irregular annular erythema with pale centre starting from around the crust corresponding to the point of tick-bite on the right knee and extending from the foot ankle to the lower third part of the thigh. (c) Case 3: an irregular annular erythema of size 5 x 7 cm with pale centre on the anteromedial part of the right thigh. (d) Case 3: superficial and deep perivascular lymphoplasmocytic inflammatory cell reaction and swollen endothelial cells in the superficial and deep dermis (arrows) [H&E; original magnification, x 40]

Case 2

A 2-year-old girl was referred to our hospital in May

2010 with a red patch on one leg that developed 10

days after a tick-bite and became increasingly large.

Dermatological examination revealed an irregular

annular erythema with pale centre starting from

around the crust corresponding to the tick-bite

on her right knee and encompassing an area from

the ankle to the lower third of the femur (Fig b).

Systemic examination was normal as were complete

blood picture and liver and renal function tests.

Borrelia burgdorferi serology was not performed.

Lyme disease was considered and treatment

was started with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid at a

paediatric dose of 50 mg/kg/day. The patient showed

clinical improvement after 15 days and there were no

systemic findings at 6-month follow-up.

Case 3

A 53-year-old female patient was referred to our

hospital in June 2010 with a red patch on her right

leg that developed about 1 month previously and had

steadily enlarged over the preceding 10 days. She had

been bitten by a tick in the same region approximately

1.5 months earlier. Dermatological examination

revealed an irregular annular erythema of about 5

x 7 cm with pale centre on the anteromedial part

of her right thigh (Fig c). Systemic questioning and

examination was normal and B burgdorferi serology,

IgM, and IgG were negative. Histopathological

examination of a skin biopsy revealed a perivascular

lymphoplasmocytic inflammatory cell reaction and

swelling of the endothelial cells in the superficial and

deep dermis. The findings were consistent with ECM

(Fig d). In view of the anamnesis and clinical and

histopathological findings, the case was diagnosed

as Lyme disease. Treatment was started with oral

doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks). Follow-up

at 15 days showed clinical improvement and the

patient had no systemic findings after 6 months.

Discussion

Lyme disease is a systemic disorder that can affect

many organs and is caused by some Borrelia species

transmitted by the Ixodes genus of ticks. There are

three genotypes of Borrelia that cause Lyme disease

in humans: Borrelia burgdorferi sensu strico, Borrelia

afzelii, and Borrelia garinii, collectively known as

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Vector-transmitted

Lyme infection is frequently seen in the United

States and Europe.1 2 3 4 5 6 7

In Turkey, the disease was first reported in

1990 in the Black Sea and Aegean Regions of the

country. To date, 25 types in the family Ixodidae

have been reported in Turkey.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ixodes ricinus may

be seen in all geographical areas of the country

but is particularly widespread in humid forest

areas (Black Sea, Marmara, and Mediterranean

regions). The definitive prevalence of B burgdorferi

infection in Turkey is unknown because of limited

investigations. Seropositivity in the general

population has been reported as 2% to 6% and in

risk groups in endemic region as 6% to 44%, but

values change with different country regions.10 11 12 13 14 Lyme disease is seen in both genders and in all

age-groups, but is more prevalent in adults aged

between 30 and 59 years and in children under 15

years of age.13 Approximately 60 cases have been

reported in Turkey since 1990. When children were

analysed, approximately 48% had a history of tick

retention and most of the skin lesions were identified

(approximately 46% in early stage). Neuroborreliosis

is the second common clinical form to be reported.

The Lyme disease is more common in women (70%)

and the age distribution is 4 to 72 years (mean, 29.1

years); cases are mostly seen between March and

July when vectors (nymphs) are active.15

Erythema chronicum migrans is the most

frequently seen and most important diagnostic skin

lesion in Lyme disease.3 6 7 It occurs on any part of

the body and appears at the site of a tick-bite after an

incubation period of 3 to 32 days, depending on the

migration of spirochaetes in the skin. The incubation

period can extend to 6 months, however.3 7 9 The

lesion that starts as a red macule or papule rapidly

expands outwards. It will then turn pale in the

centre and develop into an annular rash, giving the

appearance of a target board or bull’s eye.7 13 The diameter of the lesion varies between 4 cm and

60 cm. The lesion should have a minimal diameter of

5 cm in order to be defined as ECM. Local symptoms

such as a burning sensation, itching, or pain may be

reported.7 11

Following primary infection, the acute

disseminated stage starts with dissemination of the

causative agent to other tissues via blood and lymph

vessels. The skin findings at this stage of infection

include secondary ECM, borrelial lymphocytoma,

urticarial plaques, erythema nodosum, and a malar

rash.3 14 Secondary ECM lesions occur at sites distant from the tick-bite and will range in number from 2

to 30. The initial ECM may be followed by similar

but generally smaller and often non-migrating

lesions. More than 10 lesions are uncommon, but

may occur.3 4 7 Borrelial lymphocytoma presents

as a solitary bluish-red soft nodule with a slightly

atrophic surface that varies from 1 to 5 cm in

diameter, and occurs most frequently on the earlobe,

nipple, scrotum, or axillary region. In this stage

of dissemination, cardiac, neurological, and joint

findings predominate.1 4 7 8

After several months or years, untreated

patients may go on to develop late-stage Lyme

disease. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is

the characteristic skin lesion in this stage. Other

findings are of mono- or oligo-arthritis, meningoencephalitis,

and uveitis. This stage may be the result

of an immunopathological process in the absence of

clinical regression with antibiotic therapy, a chronic

inflammatory response, and no isolation of the

causative bacterium from the lesions.2 3 4 7 12 The three cases reported here showed only an ECM lesion and

no systemic findings at 6-month follow-up. This was

consequent to adequate therapy commenced at an

early stage of the disease.

The diagnosis of Lyme disease is based on

symptoms, objective physical findings (ECM,

facial paralysis, arthritis, etc), and a history of

tick contact.1 4 9 The results of enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay and Western blot analysis can

be used to support the diagnosis.4 9 The diagnosis of early-stage Lyme disease is based on the presence

of ECM and history of tick-bite.3 6 7 Since the rate of

false-negative results is high in the acute stage of the

disease, serological tests are not recommended, but

are used to support the clinical findings of early- and

late-disseminated stages of Lyme disease.8 9 10 11 12 Our case 1 confirmed positive IgM to B burgdorferi. Case

2 underwent no serological tests. In case 3, both IgM

and IgG were negative to B burgdorferi.

Skin biopsy is used for the differential

diagnosis of ECM. In ECM cases, there is a patch-like

perivascular mononuclear infiltration of the

superficial and deep dermis. This infiltration consists

of predominantly lymphocytes and histiocytes as

well as plasma cells in varying quantities.3 7 11 In

our case 3, histopathological examination of her

skin biopsy for differential diagnosis demonstrated

perivascular lymphoplasmocytic inflammatory cell

infiltration in the superficial and deep dermis. This

histopathological picture supported our diagnosis of

ECM.

Doxycycline, amoxicillin, and cefuroxime

axetil are the antibiotics of choice. The recommended

duration of therapy for early-stage disease is 14 to

21 days and for late stage at least 4 weeks.4 7 12 Since

our first two cases were children, they received

amoxicillin and clavulanic acid 50 mg/kg/day for

15 days. Our case 3 was an adult and received oral

doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks). At 15

days, all lesions were completely cured in all patients,

and there was no relapse or systemic involvement at

6-month follow-up.

In conclusion, ECM is an important clinical

sign of early-stage Lyme disease. The diagnosis and

therapy of Lyme disease at an early stage is vital

as it prevents progression to late-stage disease.

In endemic regions and in patients with a history

of tick-bite, the clinician should stay alert to the

presence of ECM. If a patient is considered to have

ECM, specific investigations for Lyme disease should

be ordered.

References

1. Winn WJ, Allen S, Janda W. Spirochetal infections.

Koneman’s color atlas and textbook of diagnostic

microbiology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams

and Wilkins; 2006: 1135-43.

2. Mullegger RR. Dermatological manifestations of lyme

borreliosis. Eur J Dermatol 2004;14:296-309.

3. Topcu AW, Soyletir G, Doğanay M, Doğanci L. Lyme

disease: infectious diseases and microbiology. 3. Istabul:

Nobel Tip Kitapevleri; 2008: 973-88.

4. Borriello SP, Murray PR, Funke G. Postic D. Borrelia. Topley

and Wilson’s microbiology and microbial infections. 10th

ed. London: Hodder Arnold; 2005: 1818-37.

5. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS,

Leffel DJ. In: Mahalingam M, Bhawan J, Chomat AM, Hu

L. Lyme borreliosis. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general

medicine. 7th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008: 1797-806.

6. Tepe B, Sayiner HS, Karincaoğlu Y. Early stage localized

Lyme disease: case report [in Turkish]. İnönü Üniversitesi

Tip Fakültesi Dergisi 2011;18:122-5.

7. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, Espana A. Figurate

erythemas. Dermatology. St Louis: Mosby; 2003:

277-86.

8. Evans SE, Karaduman A. Eritemli dermatozlar [in Turkish]. Turk J Dermatol 2009;3:55-62.

9. UtaŞ S, Kardag Y, Doganay M. The evaluation of Lyme

serology in patients with symptoms which may be related

with Borrelia burgdorferi [in Turkish]. Mikrobiyoloji

Bulteni 1994;28:106-12.

10. Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Wang G, Schwartz I, Wormser

GP. Diagnosis of lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev

2005;18:484-509. Crossref

11. DePietropaolo DL, Powers JH, Gill JM, Foy AJ. Diagnosis of

lyme disease. Am Fam Physician 2005;72:297-304.

12. Anlar FY, Durlu Y, Aktan G, et al. Clinical characteristics

of Lyme disease in 12 cases [in Turkish]. Mikrobiyol Bul

2003;37:255-9.

13. Koksak I, Saltoğlu N, Bingul T, Ozturk H. A case of Lyme

disease [in Turkish]. Ankem Dergisi 1990;4:284.

14. Gargili A. Lyme disease: factors and epidemiology. II.

Proceedings of Turkey Zoonotic Diseases Symposium;

2008 Nov 27-28. Ankara: Program ve Bildiri Kitabi; s:89-92.

15. Kiliç S. Lyme disease: the pathogen and epidemiology [in

Turkish]. Turkiye Klinikleri J Infect Dis Spec Top 2014;7:29-41.