© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

The Brook airway: a life-saving device

TW Wong, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)

Member, Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

The cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) technique,

as we know it today, was popularised during the

1960s. It had two components: mouth-to-mouth

ventilation and closed chest compression. Mouth-to-mouth

artificial breathing was not something new as

it was reported in the 18th century.1 Its use faded away

over the next two centuries because of the advent of

the germ theory and the belief that expired air was

unsuitable for resuscitation due to the presence of

carbon dioxide and a low oxygen concentration.2 In

the 19th century, various manual methods of artificial

ventilation were introduced and taught in first-aid

courses. James Elam, an anaesthetist from the United

States, was credited with reviving the use of mouth-to-mouth breathing in the 1950s. He demonstrated

with experiments in the operating theatre that expired

air could be used to maintain adequate arterial oxygen

saturation.3 Peter Safar, a contemporary of Elam,

also demonstrated that even laymen could be taught

to open the airway and provide adequate mouth-to-mouth ventilation in adults. He also found that

the traditional manual methods of ventilation were

ineffective to maintain oxygenation.4 5 Thus, the stage was set to introduce the kiss of life. Mouth-to-mouth

artificial ventilation in adults was endorsed by the

American Medical Association in 1958. Meanwhile,

a team from Johns Hopkins University wrote about

the effectiveness of closed-chest compression in

maintaining perfusion following cardiac arrest.6 The

term “cardiopulmonary resuscitation” was coined by

the American Heart Association in 1962 and CPR

training was gradually introduced.

Although the efficacy of mouth-to-mouth

ventilation is not in doubt, it may not be acceptable

to many. There are psychological barriers to applying

the lips on a moribund person, especially when there

may be vomitus and other secretions present. Some

form of barrier device is thus desirable. Morris Brook

(1911-1967), a general practitioner from Saskatoon,

Canada, was involved in the resuscitation of a miner

during a cave-in in 1957. This man was unconscious

and not breathing and Brook had to perform mouth-to-mouth respiration despite the presence of dirt,

blood, and vomit on the victim. The victim was

resuscitated successfully. This incident inspired

Brook to invent a device that could circumvent this

repulsive situation.7 Brook was not aware then that

Safar had already developed an S-shaped airway to

facilitate mouth-to-airway ventilation.8

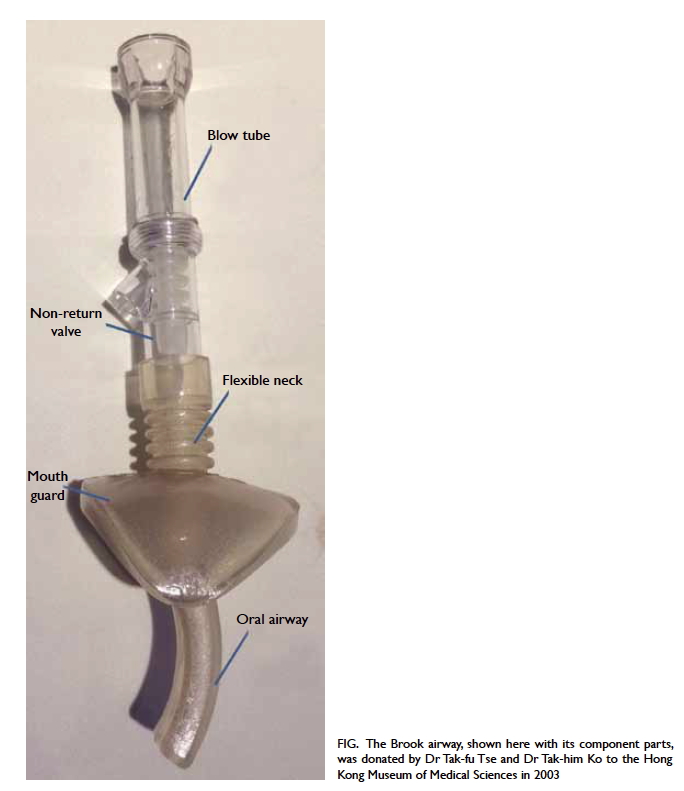

The Brook airway (Fig) was introduced around

1959 and could be clipped onto the helmets of

miners. It consisted of an oral airway that helped to

displace the tongue and maintain a patent airway.

The flexible tube made ventilation feasible even

in awkward positions. The non-return valve was

designed such that exhaled air and contents of the

stomach could escape via a separate exit without

affecting the rescuer.9 To help popularise and teach

the use of his new airway, Brook developed a wooden

‘air passage demonstrator’ and a plastic mannequin

as training aids. He also produced a documentary

film ‘That They May Live’ to teach mouth-to-mouth

respiration. The Brook airway was simple and had

an additional advantage of being more flexible in

use. It was sold to health care providers and the

public in many countries in the 1960s and 1970s.

It appears that the Brook airway was not widely

used in Hong Kong, however, and was not standard

equipment for our local ambulance service. In time,

the widespread availability of resuscitation bags and

other supraglottic devices (eg the laryngeal mask)

made Brook’s airway obsolete.

Figure. The Brook airway, shown here with its component parts, was donated by Dr Tak-fu Tse and Dr Tak-him Ko to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences in 2003

References

1. Tossach WA. A man dead in appearance recovered by distending the lungs with air. Med Essays Obs Soc Edinb 1744;part 2:605-8.

2. Baskett TF. Robert Woods (1865-1938): The rationale for mouth-to-mouth respiration. Resuscitation 2007;72:8-10. CrossRef

3. Elam JO, Brown ES, Elder JD Jr. Artificial respiration by mouth-to-mask method—A study of the respiratory gas exchange of paralyzed patients ventilated by operator’s expired air. N Engl J Med 1954;250:749-54. Crossref

4. Safar P. Ventilatory efficacy of mouth-to-mouth artificial respiration: airway obstruction during manual and mouth-to-mouth artificial respiration. J Am Med Assoc 1958;167:335-41. Crossref

5. Baskett PJ. Peter J. Safar, the early years 1924-1961, the birth of CPR. Resuscitation 2001;50:17-22. Crossref

6. Kouwenhoven WB, Jude JR, Knickerbocker GG. Closed-chest cardiac massage. JAMA 1960;173:1064-7. Crossref

7. Baskett TF. Resuscitation great. The Brook airway. Resuscitation 2006;71:6-9. Crossref

8. Safar P, McMahon M. Mouth-to-airway emergency artificial respiration. J Am Med Assoc 1958;166:1459-60. Crossref

9. Brook MH, Brook J, Wyant GM. Emergency resuscitation. Br Med J 1962;2:1564-6. Crossref