Hong Kong Med J 2017 Feb;23(1):6–12 | Epub 9 Dec 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164875

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Differences in cancer characteristics of Chinese patients with prostate cancer who present with

different symptoms

Samson YS Chan, MB, ChB, MRCS;

CF Ng, MD, FRCSEd (Urol);

Kim WM Lee, BSc, MPH;

CH Yee, MB, BS, FRCSEd (Urol);

Peter KF Chiu, MB, ChB, FRCSEd (Urol);

Jeremy YC Teoh, MB, BS, FRCSEd (Urol);

Simon SM Hou, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)

SH Ho Urology Centre, Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, The

Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof CF Ng (ngcf@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Currently there is no structured

prostate cancer screening programme in Asia.

Early diagnosis of prostate cancer in Asia is by

an opportunistic case-finding approach, that is,

offering prostate-specific antigen testing to an

individual without obvious symptoms of prostate

cancer. In this study, we investigated the

relationship between the mode of presentation and

the characteristics of prostate cancers diagnosed in

our hospital.

Methods: We recruited 120 consecutive Chinese

patients with prostate cancer newly diagnosed from

September 2011 to February 2013 in a regional hospital

in Hong Kong. Patient demographics, symptoms,

presentation, staging, and risk profiles were collected

and analysed.

Results: The number of subjects diagnosed during

a health check (group 1), investigated for symptoms

with no/low suspicion of prostate cancer (group 2),

investigated for symptoms where prostate cancer

was suspected (group 3), or who had undergone

transurethral prostatectomy (group 4) were 12

(10.0%), 53 (44.2%), 46 (38.3%), and nine (7.5%),

respectively. Overall mean age was 71.0 (range, 54-90)

years, and patients in group 3 were significantly

older than those in groups 1 and 2 (P<0.001).

Patients in group 3 had a significantly higher level

of serum prostate-specific antigen, higher incidence

of abnormal digital rectal examination, and more

metastatic disease at presentation than the other

groups. Nonetheless, more than 50% of the prostate

cancers in groups 1 and 2 were of intermediate risk

or higher staging at presentation. After a median

follow-up of 32 months, cancer-specific survival

was 100% for each of groups 1, 2, and 4 but was only

76.8% for group 3 (P=0.006).

Conclusions: Patients with prostate cancer who

presented with prostate cancer–related symptoms

had more metastatic disease and poorer survival

than patients diagnosed by a case-finding approach.

Moreover, more than half of those patients

diagnosed by case finding belonged to intermediate-

or higher-risk groups for which active treatment was

recommended.

New knowledge added by this study

- In the local Chinese population, patients with prostate cancer who presented with prostate cancer–related symptoms had more metastatic disease and poorer survival than asymptomatic patients.

- More than half of those patients with prostate cancer diagnosed by prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing (case-finding approach) had intermediate- or higher-risk disease warranting treatment.

- Health care professionals could offer PSA testing to appropriate male patients when they are seen for non-prostate-cancer–related symptoms after appropriate counselling. This may help to improve outcome and survival of prostate cancer patients.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most frequently

diagnosed cancer of men worldwide, with the

highest incidence and prevalence rates occurring in

more developed societies.1 The incidence of prostate

cancer is also increasing in Asian countries.2 Many

reasons have contributed to this recent rise in

incidence in Asia, including the increase in the

ageing population, the westernised diet, and also

the increased use of serum prostate-specific antigen

(PSA) for cancer detection.3 4 Although current

evidence supports the use of PSA testing to decrease

the incidence of metastatic disease and prostate

cancer–specific mortality,5 the use of serum PSA

for the early detection of prostate cancer is still

controversial.6 7 One of the concerns is the risk of

overdiagnosis and overtreatment of low-risk cancer

that may result in more potential harm than benefit

to patients.8 9 10 There are many types of prostate cancer screening approaches. Currently, there is no

structured prostate cancer screening programme in

Asia. Therefore, early diagnosis of prostate cancer in

Asia is by an opportunistic case-finding approach,

that is, offering PSA testing to an individual without

obvious signs and symptoms of prostate cancer.

Information on the characteristics of prostate cancer

diagnosed by various approaches in Asia is lacking,

however. We postulated that patients diagnosed by

a case-finding approach, such as during a routine

health check or a consultation for symptoms with

a low suspicion of prostate cancer origin, would

have a better prognosis than those who presented

with symptoms related to prostate cancer, with or

without metastatic disease. We investigated the

relationship between the mode of presentation and

the characteristics of prostate cancers diagnosed in

our hospital.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study to assess

consecutive adult male patients diagnosed with

prostate cancer at Prince of Wales Hospital, a

regional hospital in Hong Kong, between September

2011 and February 2013. Institutional ethics approval

was obtained for the study. Informed consent was

obtained from all study subjects prior to enrolment

in the study.

All patients aged 18 years or above at our

hospital with histological confirmation of prostate

cancer were identified and approached for inclusion

in this study. After informed consent was obtained,

information on the initial presentation of the

patient’s condition, prostate cancer characteristics

at diagnosis, and the initial treatment plan were

collected. Patients were then followed up for a

minimum of 2 years, and the clinical outcome was

assessed. All cancer was graded using the Gleason

grading system that is based on the histological

pattern of the cancer tissue. The tissue was

graded from 1 (well-differentiated) to 5 (poorly

differentiated). Each biopsy was given two scores,

the first indicated the most common pattern and the

second, the highest grading.11 Our scoring system

for prostate cancer consists of staging according to

TNM staging 201012 and risk stratification according

to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network

(NCCN) guideline.13

Subjects were divided into four groups

according to the initial clinical presentation of

their prostate cancer by two investigators who were

blinded to the clinical outcome during the assessment

and then confirmed by a senior investigator. Any

discrepancy was discussed and a final allocation

made. The health check group (group 1) included

patients in whom a raised PSA was detected during

a routine health check. Group 2 comprised patients

diagnosed with prostate cancer by the case-finding

approach after they presented with symptoms with

no/low clinical suspicion of prostate cancer (eg

renal cysts, non-specific abdominal pain). Group 3

comprised patients with a high clinical suspicion of

prostate cancer or malignant disease, for example,

lower urinary tract symptoms with abnormal digital

rectal examination (DRE), bone pain, or weight loss.

Finally, those patients with a histological diagnosis

of prostate cancer made following transurethral

resection of the prostate (TURP) but with no

preoperative suspicion of prostate cancer were

assigned to the TURP group (group 4).

Since prostate cancer arises mostly from the

peripheral zone (in contrast to benign prostate

hyperplasia [BPH] that commonly arises from the

transition zone), patients with early-stage prostate

cancer are usually asymptomatic.14 Not until the

tumour becomes locally advanced (with clinical

signs of abnormal DRE) do patients have voiding

symptoms attributed to prostate cancer. Therefore,

in a patient who presents with lower urinary tract

symptoms (LUTS) and normal DRE, the symptoms

are more likely related to BPH, not secondary to

prostate cancer. Testing of PSA is not routine for male

patients with LUTS.15 16 According to the Guidelines

from the European Association of Urology, PSA

measurement should only be performed to assess

the risk of progression of LUTS or if a diagnosis of

prostate cancer would change disease management.16

For patients who present with LUTS but with a low

clinical suspicion of prostate cancer (ie normal DRE),

PSA testing is considered case-finding for prostate

cancer. In this study, such patients were assigned

to group 2. This also applied to other presenting

symptoms with no or low suspicion of being related

to prostate cancer. Nonetheless, in subjects with

LUTS and clinical symptoms or signs suspected to be

secondary to prostate cancer, such as abnormal DRE

findings, PSA testing would be part of the diagnostic

process for prostate cancer, not case-finding. As a

result, these patients would be assigned to group 3.

After all data were collected, descriptive

statistics were applied. A Chi squared test or Fisher’s

exact test was used to determine any relationship

between the categorical outcome measures. Analysis

of variance or Kruskal-Wallis test was used for

normal or skewed data, and then followed by post-hoc

comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was applied to analyse

survival among the four groups. Data management

and analysis were performed using the Statistical

Package for the Social Sciences (Windows version

22.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). A two-tailed test

was used with significance set at P<0.05.

Results

From September 2011 to February 2013, 126

consecutive patients with newly diagnosed,

histologically confirmed prostate cancer were

managed in our centre. One patient refused to

participate in this study, and five patients were not

capable of providing informed consent. Therefore 120

patients were enrolled in this study: group 1 (n=12),

group 2 (n=53), group 3 (n=46), and group 4 (n=9)

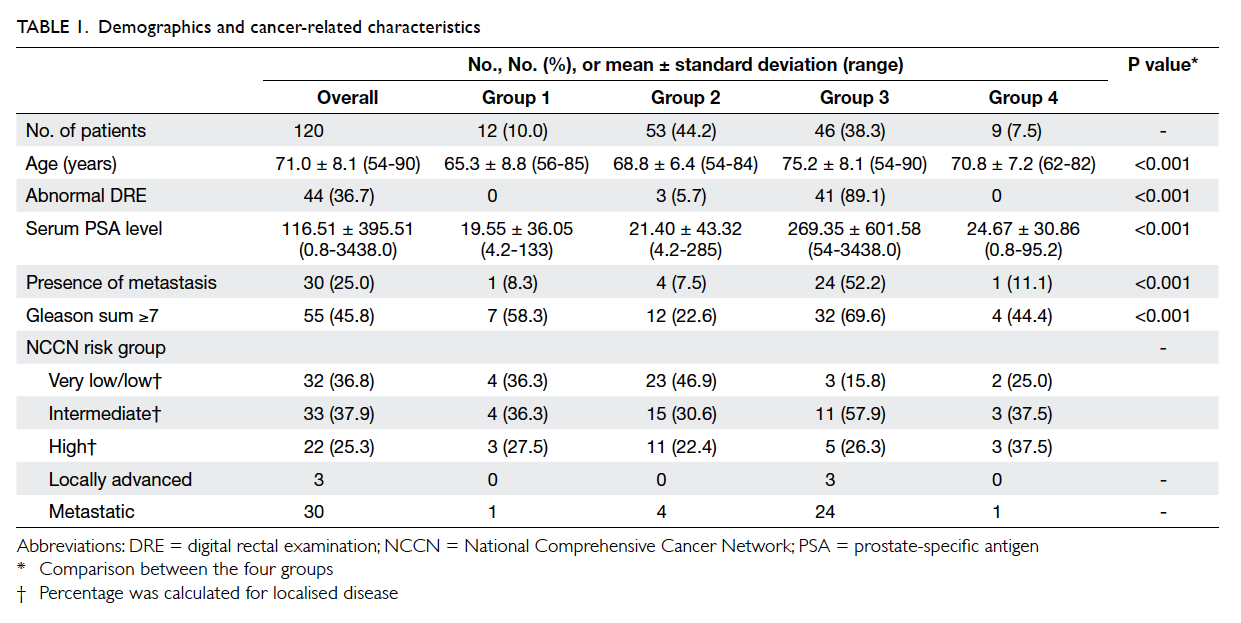

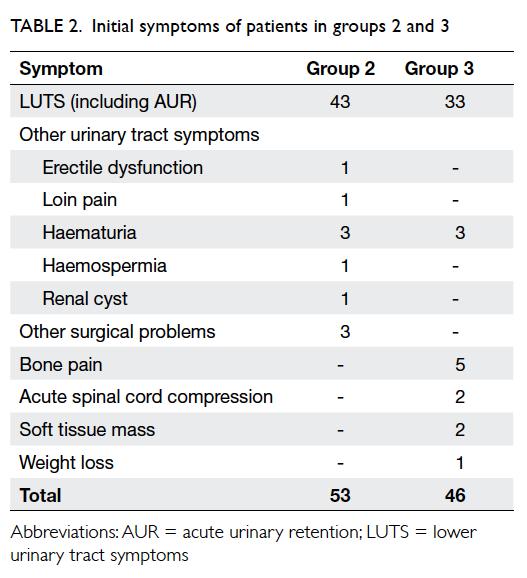

[Table 1]. The initial presenting symptoms of patients in groups 2 and 3 are listed in Table 2. In group 2, 43 patients presented with LUTS (including three with

acute urinary retention) with low clinical suspicion

of prostate cancer. Ten patients presented with other

symptoms—seven with other urological symptoms

and three with other general surgical problems.

Among them, three patients (one with loin pain, one

with erectile dysfunction, and one with hernia) were

found to have abnormal DRE during consultation.

In group 3, 33 patients presented with LUTS (nine

patients with acute urinary retention) and abnormal

DRE. Three patients presented with haematuria

and DRE during initial workup was abnormal and a

subsequent diagnosis was made of prostate cancer.

Nine patients presented with metastatic symptoms,

eg bone pain, acute spinal cord compression, and

abnormal soft tissue mass. One patient presented

with weight loss and was subsequently diagnosed to

have non-metastatic prostate cancer (Table 2).

The overall mean age was 71.0 (range, 54-90)

years (Table 1). Age and serum PSA level were statistically significantly different across groups. Multiple

comparisons with Bonferroni correction revealed

that patients in group 3 were significantly older

than those in groups 1 and 2 (P<0.001). Patients in

group 3 also had a significantly higher serum PSA

level compared with those in group 1 (P=0.044) and

group 2 (P=0.045) by Kruskal-Wallis test. In group

3, 41 (89.1%) patients had an abnormal DRE

(P<0.001).

With regard to disease status, the numbers

of patients with a Gleason sum of ≥7 were seven

(58.3%) in group 1, 12 (22.6%) in group 2, 32

(69.6%) in group 3, and four (44.4%) in group 4. In

accordance with the NCCN guideline, the number

of patients with disease more severe than very low

or low risk were eight (66.7%) in group 1, 30 (56.6%)

in group 2, 43 (93.5%) in group 3, and seven (77.8%)

in group 4 (Table 1). In group 3, 24 (52.2%) patients had metastatic disease at initial presentation, a

much higher rate than in the other groups (P<0.001,

Fisher’s exact test).

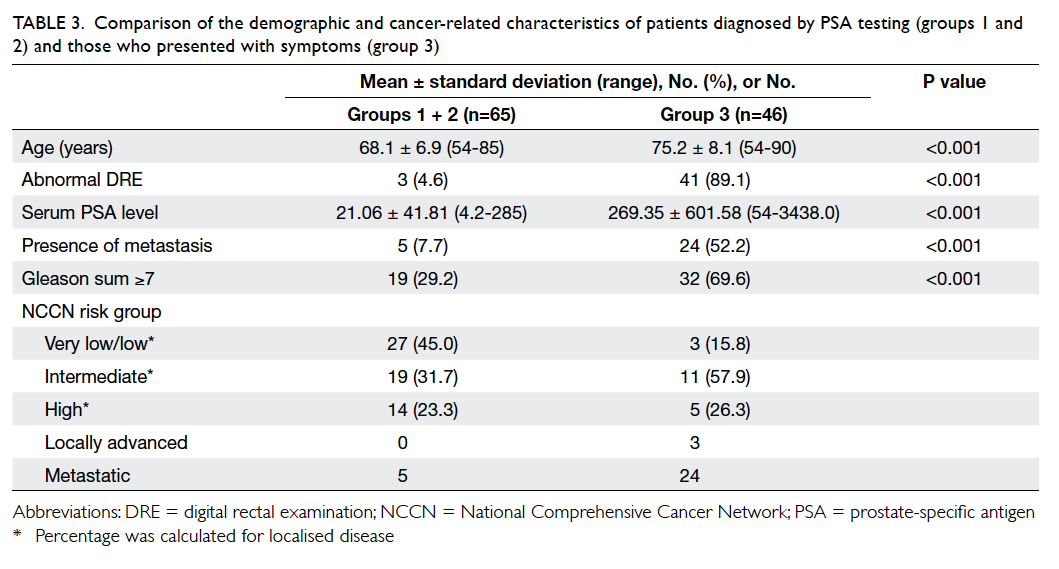

Since both groups 1 and 2 had no prostate

cancer–related symptoms, we tried to combine the

two groups to assess the characteristics of prostate

cancer diagnosed by a case-finding approach. Group

3 patients had significantly older age, higher serum

PSA level, more aggressive disease (Gleason sum

≥7), and more metastatic disease at presentation

than the combined groups 1 and 2 patients (P<0.001

for all parameters; Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of the demographic and cancer-related characteristics of patients diagnosed by PSA testing (groups 1 and 2) and those who presented with symptoms (group 3)

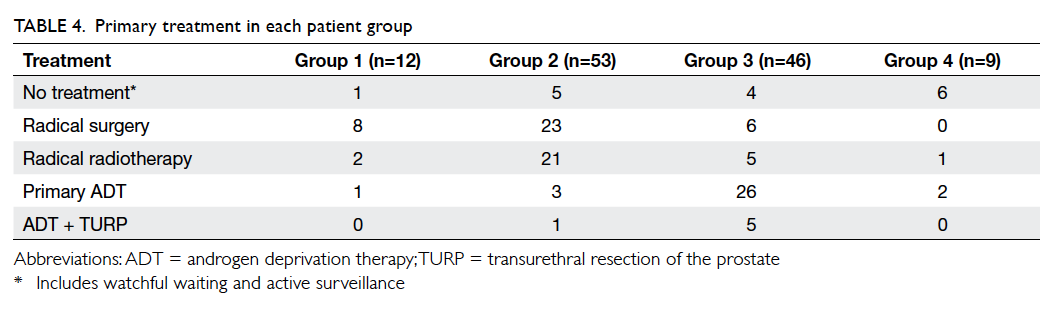

The types of primary treatment administered

are listed in Table 4. The number of patients receiving radical local therapy (either surgery or

radiotherapy) was 10 (83.3%) in group 1, 44 (83.0%)

in group 2, 11 (23.9%) in group 3, and one (11.1%) in

group 4. Systemic androgen deprivation therapy was

prescribed to one (8.3%) patient in group 1, three

(5.7%) in group 2, 26 (56.5%) in group 3, and two

(22.2%) in group 4 (P<0.0005). Because group 3 had

significantly more patients with locally advanced

and metastatic disease, significantly fewer could be

managed with curative-intent local therapy. Among

those patients with very low– or low-risk disease in

groups 1 and 2, one (25%) and five (21.7%) respectively

elected to have conservative management, either

watchful waiting or active surveillance.

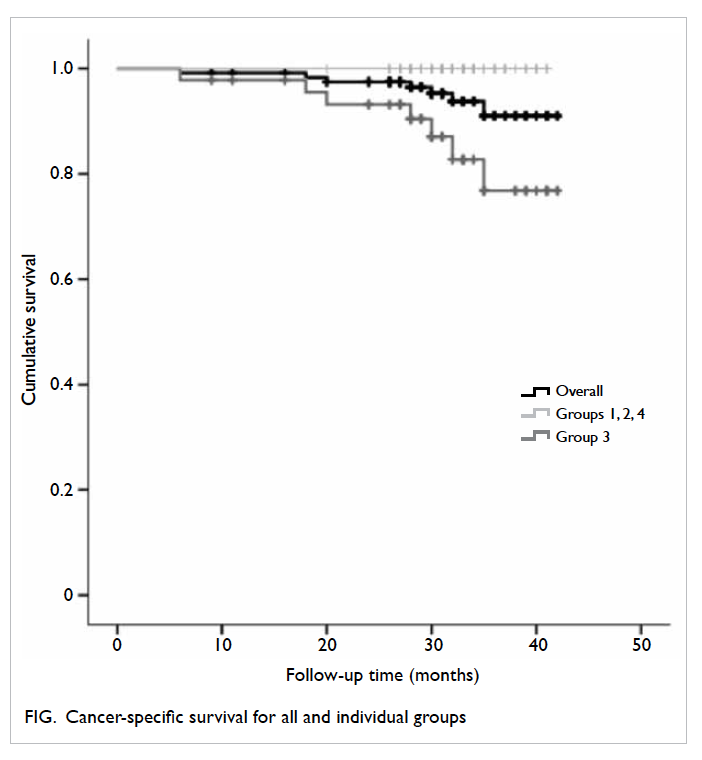

The median follow-up period was 32 months

(interquartile range, 28-35 months). No patients were

lost to follow-up. Eleven (9.2%) patients died—10

(21.7%) in group 3 and one (11.1%) in group 4. No

patient in groups 1 or 2 died during the follow-up

period. The causes of death in group 3 patients were

directly related to prostate cancer in seven patients,

metastatic bladder cancer in one patient, and acute

myocardial infarction in two patients. The cause of

death of the patient in group 4 was secondary to

advanced rectosigmoid carcinoma. Therefore, the

overall rate of cancer-specific survival for the total

cohort was 91.0%, but 100% for each of groups

1, 2, and 4 compared with only 76.8% for group 3

(P=0.006, log-rank test; Fig).

Discussion

Since the introduction of PSA testing, there has

been a worldwide change in the presentation of

prostate cancer. More and more prostate cancers

are diagnosed at a lower risk level and earlier stage

for which curative treatment can be offered.17 18 As a

result, the use of PSA testing for early detection of

prostate cancer is believed to be one of the factors

that has led to the decrease in overall prostate

cancer mortality in many developed areas.2 From

our cohort, we also observed that patients with

prostate cancer diagnosed by case-finding approach

using PSA testing (groups 1 and 2) had significantly

more clinically localised disease and hence a higher

chance of receiving curative-intent treatment than

those patients who presented with prostate cancer–related symptoms (group 3).

We also observed that the short-term cancer-specific

mortality rate of patients who presented

with prostate cancer–related symptoms (group

3) was significantly higher than that in the other

groups. In our cohort, more than half of the patients

in group 3 already had metastasis at diagnosis.

Because patients presenting with metastasis have a

much poorer outcome than other patients,19 20 it was

not surprising that the mortality rate for patients

who presented with symptoms was also higher. This

indirectly supports the case-finding approach by

PSA testing in patients with symptoms but no/low

clinical suspicion of prostate cancer, as it might help

to decrease the incidence of metastatic disease and

hence the mortality related to prostate cancer.21

Although PSA testing is widely performed in

western countries to detect early prostate cancer, its

use in Asian countries is still not a common practice.

From a population-based telephone survey involving

1002 Chinese men aged ≥50 years in Hong Kong,

only 9.5% had ever had a PSA test, and only 3.7% of

the total sample had PSA test done during a routine

health check.22 Even in more developed Asian

countries such as Japan and South Korea, only 15% to

20% of the population had had a PSA test.23 Only 10%

of the prostate cancers in our cohort were diagnosed

during a self-initiated health check with PSA testing.

Therefore, offering a PSA test as case-finding for

prostate cancer during a patient’s consultation

for non-prostate-cancer–related symptoms is an

alternative approach for early detection of prostate

cancer. We believe that this case-finding approach is

feasible for the detection of early prostate cancer in

our region, where public awareness and use of PSA

testing is still low. Certainly, patients need to be well

informed about the nature and implications of PSA

testing before the test is performed.24 25

The main concerns surrounding the use of

PSA testing for the detection of early prostate

cancer are overdiagnosis and overtreatment.8 9 10 Only

approximately 36% of patients in the study cohort

had very low– or low-risk disease that might not

require aggressive intervention.13 26 Even in those

patients with prostate cancer diagnosed by PSA

testing (ie groups 1 and 2), more than 50% were in

the intermediate- or higher-risk groups. Testing of PSA

level did help to detect patients with significantly

high-risk prostate cancer that warranted further

treatment. To minimise the risk of overtreatment,

the Melbourne Consensus Statement advises

uncoupling of the prostate cancer diagnosis from

the intervention.5 Offering active surveillance to

patients with low-risk disease will help to minimise

the potential harm of overtreatment. In our cohort,

for patients in groups 1 and 2 with very low– or low-risk

disease, six (22.2%) opted for observation with

no active treatment. We believe this concept should

be promoted to both clinicians and patients, rather

than limiting the use of PSA testing for the case

finding of prostate cancer.

Currently, some newly proposed strategies,

such as determination of the baseline PSA level

earlier in life27 28 and the use of newer diagnostic

tools,29 30 might help to reduce unnecessary prostatic

biopsies and overdiagnosis of low-risk prostate

cancer. Nonetheless, since most of these studies were

conducted in Caucasian-based populations, further

studies in Asian populations are necessary to verify

their suitability in our region.

Although our data show that the short-term

outcome of patients who present with prostate

cancer–related symptoms seems to be worse than

those diagnosed by PSA testing, this might be due

to potential lead-time bias, that is, the increase in

survival is actually due to the length of time between

the detection of a disease by PSA testing and its usual

clinical presentation and diagnosis. This will result

in an increase in survival time for patients diagnosed

by PSA testing. Other potential bias is length-time

bias which suggests that annual PSA may only detect

slow-growing tumours, that screening for prostate

cancer does not detect the very tumour for which it

is intended.

The aim of our study was not to assess the role of

PSA testing in the detection of early prostate cancer

or its effect on long-term outcome and survival of

patients. Rather, we aimed only to compare cancer

characteristics and short-term outcome among

patients with different presentations. We also did

not analyse the potential harm of PSA testing,

prostatic biopsy, or morbidities related to treatment.

The positive rate for prostatic biopsy depends on

the level of serum PSA and DRE finding. From

local experience, for patients with a normal DRE,

the positive rate of prostatic biopsy for serum PSA

level of 4-10 ng/mL and 10-20 ng/mL was only 6.7%-13.4% and 10.3%-21.8%, respectively.31 32 33 Therefore,

information on this would be helpful during patient

counselling for prostatic biopsy. Another limitation

of our study was the relatively small sample size from

a single centre in Hong Kong, therefore our results

might not represent the general situation in Hong

Kong. Further studies, especially with multicentre

collaboration, may help to confirm the applicability

of our results in the local population.

Conclusions

Patients with prostate cancer presenting with related

symptoms had more metastatic disease and poorer

survival than those diagnosed by a case-finding

approach using PSA testing during a health check

or management of symptoms with a low suspicion

of prostate cancer. More than half of the patients

diagnosed by this case-finding approach belonged to

intermediate- or higher-risk groups for which active

treatment was recommended. Apart from a self-initiated

health check with PSA testing, offering PSA

testing to appropriate patients who present with

symptoms with no/low clinical suspicion of prostate

cancer is an alternative approach to early diagnosis

of prostate cancer. Pre-test counselling, including

the discussion of potential bias (such as lead time

or length-time bias), is essential. This may hopefully

help to improve the short-term outcome for these

patients.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J,

Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin

2015;65:87-108. Crossref

2. Center MM, Jemal A, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. International

variation in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates.

Eur Urol 2012;61:1079-92. Crossref

3. Sim HG, Cheng CW. Changing demography of prostate

cancer in Asia. Eur J Cancer 2005;41:834-45. Crossref

4. Pu YS, Chiang HS, Lin CC, Huang CY, Huang KH, Chen

J. Changing trends of prostate cancer in Asia. Aging Male

2004;7:120-32. Crossref

5. Murphy DG, Ahlering T, Catalona WJ, et al. The Melbourne

Consensus Statement on the early detection of prostate

cancer. BJU Int 2014;113:186-8. Crossref

6. Schröder FH. Landmarks in prostate cancer screening.

BJU Int 2012;110 Suppl 1:3-7. Crossref

7. Alberts AR, Schoots IG, Roobol MJ. Prostate-specific

antigen-based prostate cancer screening: past and future.

Int J Urol 2015;22:524-32. Crossref

8. Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl

Cancer Inst 2010;102:605-13. Crossref

9. Loeb S, Bjurlin MA, Nicholson J, et al. Overdiagnosis and

overtreatment of prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2014;65:1046-55. Crossref

10. Stone NN, Crawford ED. To screen or not to screen: the

prostate cancer dilemma. Asian J Androl 2015;17:44-5. Crossref

11. Epstein JI. An update of the Gleason grading system. J Urol

2010;183:433-40. Crossref

12. Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fitz AG, Greene FL, Trotti

A. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York, NY:

Springer; 2010.

13. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical

Practice Guidelines in Oncology—Prostate cancer, version

1.2015. Available from: http://www.nccn.org. Accessed 1

Jul 2015.

14. Loeb S, Carter HB. Early detection, diagnosis, and staging

of prostate cancer. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et

al, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th ed. Philadelphia,

PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012: 2763-70. Crossref

15. European Association of Urology. Guidelines on the

management of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract

symptoms (LUTS), incl. benign prostatic obstruction

(BPO). Available from: http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/EAU-Guidelines-Non-Neurogenic-Male-LUTS_LR.pdf. Accessed 1 Jul 2015.

16. Arianayagam M, Arianayagam R, Rashid P. Lower urinary

tract symptoms—current management in older men. Aust

Fam Physician 2011;40:758-67.

17. Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Mehta SS, Carroll PR,

CaPSURE. Time trends in clinical risk stratification for

prostate cancer: implications for outcomes (Data from

CaPSURE). J Urol 2003;170(6 Pt 2):S21-7. Crossref

18. Crawford ED. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. Urology

2003;62(6 Suppl 1):3-12. Crossref

19. Chowdhury S, Robinson D, Cahill D, Rodriguez-Vida

A, Holmberg L, Møller H. Causes of death in men with

prostate cancer: an analysis of 50,000 men from the Thames

Cancer Registry. BJU Int 2013;112:182-9. Crossref

20. Patrikidou A, Loriot Y, Eymard JC, et al. Who dies

from prostate cancer? Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis

2014;17:348-52. Crossref

21. Wu JN, Fish KM, Evans CP, Devere White RW, Dall’Era

MA. No improvement noted in overall or cause-specific

survival for men presenting with metastatic prostate

cancer over a 20-year period. Cancer 2014;120:818-23. Crossref

22. So WK, Choi KC, Tang WP, et al. Uptake of prostate cancer

screening and associated factors among Chinese men aged

50 or more: a population-based survey. Cancer Biol Med

2014;11:56-63.

23. Baade PD, Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Dunn J, Gardiner RA.

Epidemiology of prostate cancer in the Asia-Pacific region.

Prostate Int 2013;1:47-58. Crossref

24. Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, et al. Early detection of

prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol 2013;190:419-26. Crossref

25. Basch E, Oliver TK, Vickers A, et al. Screening for prostate

cancer with prostate-specific antigen testing: American

Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion.

J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3020-5. Crossref

26. European Association of Urology. Guidelines on prostate

cancer. Available from: http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/09-Prostate-Cancer_LRV2-2015.pdf. Accessed 1

Jul 2015.

27. Lilja H, Cronin AM, Dahlin A, et al. Prediction of significant

prostate cancer diagnosed 20 to 30 years later with a single

measure of prostate-specific antigen at or before age 50.

Cancer 2011;117:1210-9. Crossref

28. Vickers AJ, Ulmert D, Sjoberg DD, et al. Strategy for

detection of prostate cancer based on relation between

prostate specific antigen at age 40-55 and long term risk of

metastasis: case-control study. BMJ 2013;346:f2023. Crossref

29. Braun K, Sjoberg DD, Vickers AJ, Lilja H, Bjartell AS. A

four-kallikrein panel predicts high-grade cancer on biopsy:

independent validation in a community cohort. Eur Urol

2016;69:505-11. Crossref

30. Stattin P, Vickers AJ, Sjoberg DD, et al. Improving the

specificity of screening for lethal prostate cancer using

prostate-specific antigen and a panel of kallikrein markers:

a nested case-control study. Eur Urol 2015;68:207-13. Crossref

31. Ng CF, Ng MT, Yip SK. Urology update 2—Management of

uro-oncology and associated urological symptoms. Hong

Kong Pract 2009;31:128-32.

32. Ng CF, Chiu PK, Lam NY, Lam HC, Lee KW, Hou SS. The

Prostate Health Index in predicting initial prostate biopsy

outcomes in Asian men with prostate-specific antigen

levels of 4-10 ng/mL. Int Urol Nephrol 2014;46:711-7. Crossref

33. Teoh JY, Yuen SK, Tsu JH, et al. Prostate cancer detection

upon transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy in relation to

digital rectal examination and prostate-specific antigen

level: what to expect in the Chinese population? Asian J

Androl 2015;17:821-5.