Hong Kong Med J 2016 Oct;22(5):496–505

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164920

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE CME

Opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain: guidelines for Hong Kong

CW Cheung, MD, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)1;

Timmy CW Chan, FFPM ANZCA, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)2;

PP Chen, FFPM ANZCA, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)3;

MC Chu, FFPM ANZCA, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)4;

William CM Chui, MSc, BPharm (Hon)5;

PT Ho, FRCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry)6;

Flori Lam, BHSc(RN)7;

SW Law, FRCSEd(Orth), FHKCOS8;

Josephine LY Lee, MSc9;

Steven HS Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)7;

Vincent KC Wong, BCPS, MPharm5

1 Laboratory and Clinical Research Institute for Pain, Department of Anaesthesiology, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Department of Anaesthesiology, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

3 Department of Anaesthesiology and Operating Services, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Tai Po, Hong Kong

4 Department of Anaesthesia, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

5 Department of Pharmacy, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

6 Consultation and Liaison Psychiatry Team, Kwai Chung Hospital, Kwai Chung, Hong Kong

7 Department of Anaesthesiology and Operating Theatre Services, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

8 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

9 Occupational Therapy Department, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CW Cheung (cheucw@hku.hk)

Abstract

Opioids are increasingly used to control chronic

non-cancer pain globally. International opioid

guidelines have been issued in many different

countries but a similar document is not generally

available in Hong Kong. Chronic opioid therapy has

a role in multidisciplinary management of chronic

non-cancer pain despite insufficient evidence for

its effectiveness and safety for long-term use. This

document reviews the current literature to inform

Hong Kong practitioners about the rational use of

chronic opioid therapy in chronic non-cancer pain. It

also aims to provide useful recommendations for the

appropriate, effective, and safe use of such therapy

in the management of chronic non-cancer pain in

adults. Physicians should conduct a comprehensive

biopsychosocial evaluation of patients prior to the

commencement of opioid therapy. When opioid use

is deemed appropriate, the patient should provide

informed consent within an agreement that specifies

treatment goals and expectations. A trial of opioid

can be commenced and, provided there is progress

towards treatment goals, then chronic therapy

can be considered at a dose that minimises harm.

Monitoring of effectiveness, safety, and drug misuse

should be continued. Treatment should be stopped

when opioids become ineffective, intolerable,

or misused. The driving principles for opioid

prescription in chronic pain management should

be: start with a low dose, titrate slowly, and maintain

within the shortest possible time.

Introduction

Chronic pain is pain that persists beyond the usual

time of healing, usually marked as 6 months or even

3 months by the International Association for the

Study of Pain (IASP).1 Chronic pain arises from

complex changes to central or peripheral nervous

system signalling, or both. The perception of pain

is modulated by an individual cognitive factors and

the environment,2 and can significantly compromise

daily function, resulting in an important health issue.

Hong Kong survey data estimated the prevalence of

chronic pain to affect 10.8% of the population in 2000

and 35% in 2007.3 4 Survey participants with chronic pain from an earlier study reported a significant

impact on their daily lives.3 Moreover, chronic pain

placed a substantial load on productivity, with an

estimated loss of approximately 0.2 working days per

person in the working population per year, and on

health care resources, with almost three quarters of

respondents consulting a health care practitioner.

The latter survey found that reports of chronic pain

were strongly associated with co-morbid mental

health problems and anxiety.4

Opioid therapy is accepted for acute pain

and cancer pain,5 6 but its effectiveness and safety for chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) remains

contentious. By definition, CNCP refers to non-malignant

pain that lasts beyond the time of tissue

healing, or longer than 3 months.1 Authors cite weak

evidence for opioid use for CNCP due to the lack of

randomised controlled trials with long follow-up.7 8 Based on systematic reviews, opioids for CNCP—including neuropathic pain, nociceptive pain, and arthritic pain—confer some benefit by reducing

pain intensity and improving functional outcome

compared with placebo and other non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs,9 10 11 12 13 but high-quality studies

are rare, and treatment duration is short, ranging

from 2 weeks to 6 months. A proportion of patients in

the studies reviewed did not progress to long-term

therapy due to adverse effects.12 Discontinuation

rates from adverse effects were almost 30%, with the

most frequently reported events being constipation,

nausea, dizziness, drowsiness, and headache.12

The potential to develop opioid abuse or

addiction with long-term therapy is also a concern.

In studies reviewed, addiction or abuse rates were

reported to range from 0.27% to 0.43%.12 14 15 Deaths

related to opioid analgesic overdose have been

increasing, and is being linked to an increase in opioid

prescriptions for pain.16 17 Indeed, chronic opioid exposure from prescription appears to be a strong

risk factor for an opioid misuse event in patients just

diagnosed with CNCP.18 Other potential harm from

chronic opioid use includes increased fracture risk,19

androgen deficiency,20 respiratory depression,21 cognitive impairment,22 impaired immunity,23 and opioid-induced hyperalgesia.24 25

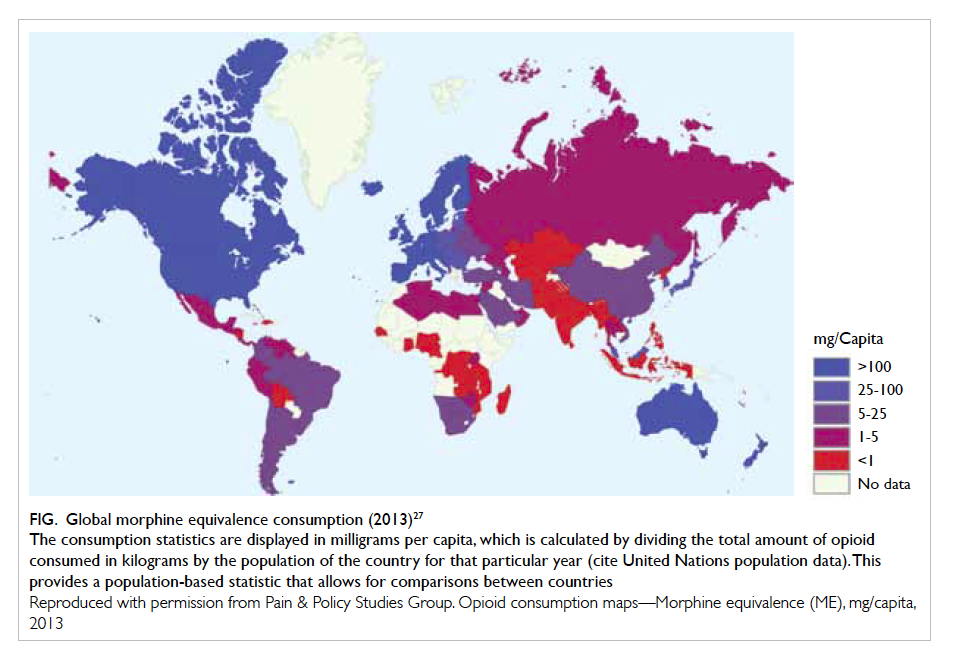

Global consumption of opioids for moderate-to-severe pain increased approximately 15-fold from 1980 to 2012.26 Generally, opioid consumption

of countries in Asia, including Hong Kong, is low

relative to the global picture (Fig27), but showing an increasing trend.27 28 Physicians in Hong Kong may be reluctant to prescribe opioids for long-term

therapy due to fear of patient addiction. There

may also be a cultural prejudice against opioid use

stemming from a history of China’s involvement in the

global opium trade in the early part of the century.29

Other possible barriers to prescription and patient

care may include inadequate physician education

about pain management, and lack of physician-patient

communication about the seriousness of

the pain problem. The absence of a central registry

for opioid prescriptions, and the limited number

of addiction specialists are potential local logistical

barriers. With the introduction of opioid choices

in Hong Kong, however, the prescription of strong

opioids for long-term treatment may become more

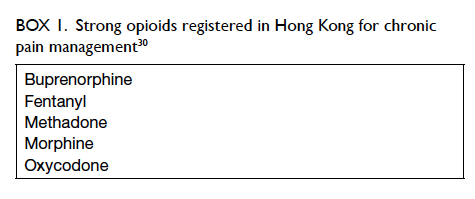

common. Examples of strong opioids for CNCP

used in Hong Kong are listed in Box 1.30

Figure. Global morphine equivalence consumption (2013)27

The consumption statistics are displayed in milligrams per capita, which is calculated by dividing the total amount of opioid consumed in kilograms by the population of the country for that particular year (cite United Nations population data). This provides a population-based statistic that allows for comparisons between countries

Reproduced with permission from Pain & Policy Studies Group. Opioid consumption maps—Morphine equivalence (ME), mg/capita, 2013

Guidelines governing the use of opioids for

patients with CNCP have been issued in different

countries according to their needs.31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 The Hospital

Authority has recently introduced an opioid

guideline for CNCP for public hospital use. A similar

guide is not readily available for physicians who are

involved in CNCP management but practise outside

Hospital Authority in Hong Kong. This document

aims to serve as a resource and uniform guide for

the appropriate, effective, and safe use of chronic

opioid therapy (COT) in the management of CNCP

in adults based on local considerations; COT is

regarded as the use of strong opioids for more than 3

months.39 This guideline provides recommendations

about patient selection, risk screening, initiation

of COT, and monitoring during COT, based on a

review of the current literature. The target audience

is all physicians, especially non-pain specialists,

and other health care professionals involved in the

multidisciplinary management of the patient with

CNCP, who are considering prescribing COT.

General considerations for using opioid in patients with chronic non-cancer pain

The biopsychosocial model describes pain as bodily

disruption shaped by an individual’s subjective

perception. Biological processes, emotions, and

social factors all influence the pain experience.2

Consequently, chronic pain is a complex condition

that requires a multidisciplinary approach to

both evaluation and management, preferably in a

coordinated treatment programme.40 41 The IASP recognises the effectiveness of multidisciplinary pain

programmes for chronic pain, and recommended the

establishment of multidisciplinary pain clinics or pain

centres; the latter of which should be associated with

a research or academic programme.40 Staff at both

pain centres and clinics should include practitioners

from various disciplines deemed expert in pain

management. Physicians, nurses, mental health

professionals, and physical therapists are among

those who comprise a team that coordinates diagnosis

and management, with constant communication,

preferably in one setting.40 41 Essential elements of multidisciplinary pain programmes address pain

management, psychosocial recovery, and physical

rehabilitation, and include medication, physical

therapy, and cognitive and behavioural strategies.42

Such programmes have been proven clinically effective and

cost-effective.43 44 45

In fact, COT is just part of the multimodal strategy to manage CNCP. Experts do not

recommend opioids for first-line treatment of

CNCP.34 36 38 Non-opioid treatment options, both

non-pharmacological and pharmacological (eg typical analgesics), should be tried first. Despite

limited evidence to support the safe and effective

use of opioids in CNCP, they may be considered

for selected patients who have moderate-to-severe

pain and who have not responded adequately

to non-opioid therapy.38 In accordance with

the biopsychosocial model, treatment of CNCP

should address the physical, psychological, and

social aspects of the pain problem.41 Treatment

of CNCP should thus aim to reduce pain and

support patients’ physical, psychological, social,

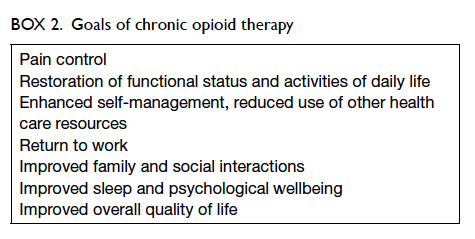

and work functioning.40 The goals of COT include

pain reduction, reduction of pain-associated

symptoms such as anxiety and sleep problems,

and improvement of daily function.46 47 These goals should be individualised and utilise achievable

milestones without excessive use of opioids.46 Indeed,

daily function outcomes were deemed important by

survey participants with chronic pain,48 and should

be targets for improvement along with pain control

(Box 2).

Recommendations

- Chronic opioid therapy should be considered only as part of a multidisciplinary pain management strategy.

- Opioids should be prescribed only after exhausting other pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment options.

- Treatment goals acceptable to both patients and their physicians should be set when COT is considered.

- When prescribed, COT should aim to reasonably reduce pain and its associated symptoms, as well as improve functional outcomes.

Patient evaluation and selection

Prior to starting COT, a comprehensive patient

evaluation should be carried out to form a diagnosis,

establish the cause of pain, describe pain intensity,

and determine a patient’s risk profile with the

use of opioids.38 46 The evaluation informs on the suitability of a patient for COT, and, if the decision

to pursue COT is made, provides the foundation

for individualising a treatment plan. A thorough

history and physical examination with appropriate

investigations are essential. The pain complaint

should be thoroughly investigated with regard to

characteristics, underlying factors, and effects on the

patient’s functional status.38 46 Assessment should include a medical and psychosocial history, including

previous medication, general health, family support,

and work status. For example, increased use of

opioids for pain control prior to spine surgery was

found to be associated with worse postoperative

outcomes, such as increased demand for opioids

after surgery, and decreased incidence of opioid

independence 1 year after surgery.49 50 This highlights the need for a complete evaluation and screening of

each patient prior to opioid use. Evaluation findings

may impact subsequent patient counselling and

treatment planning.

The rate of problematic opioid use or aberrant

drug–related behaviour in patients with CNCP on

COT is 11.5%.51 Prevalence of substance use disorder

among patients with CNCP, with or without opioid

use, ranges from 3% to 48%.52 Because problematic

opioid use complicates pain treatment and may

cause significant harm, a patient’s risk for opioid

abuse, misuse, or addiction must be assessed prior

to COT.38 46 53 54 Screening helps the physician to

anticipate the patient’s risk of developing aberrant

behaviour while on COT.53 54 Family and personal history of substance abuse, a history of psychiatric

or mood disorders, and younger age have not been

validated as predictive of opioid misuse, but have

been shown to potentially increase risk.52 55 56

The physician can utilise structured clinical

interviews and self-reports to elicit these factors.52 56

Questionnaires such as the Opioid Risk Tool, which

assigns weights to predictive factors of opioid

misuse, may be useful.57 The presence of apparent

predictors of misuse such as a personal or family

history of substance abuse or addiction does not

necessarily preclude the use of opioids, but may

affect structure of therapy (eg closer monitoring,

stricter prescription practice) and require

additional consultation from specialists, including

psychiatrists.54 Urine drug screening (UDS) may be

a useful aid in detection of latent drug abuse. Every

assessment must be thoroughly documented.

According to addiction specialists from the

Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists, screening by

psychiatrists for suitability of high-risk patients

for COT may not be useful, as evidence to support

reduced substance abuse risk through conjoint

selection by pain specialists and psychiatrists is

lacking. There is also inadequate evidence that the

future risk of opioid abuse is reduced by treating

substance abuse prior to COT; thus, the decision to

make this treatment a prerequisite for COT rests on

the pain management team (written communication,

Clinical Division of Substance Abuse & Addiction

Psychiatry, Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists,

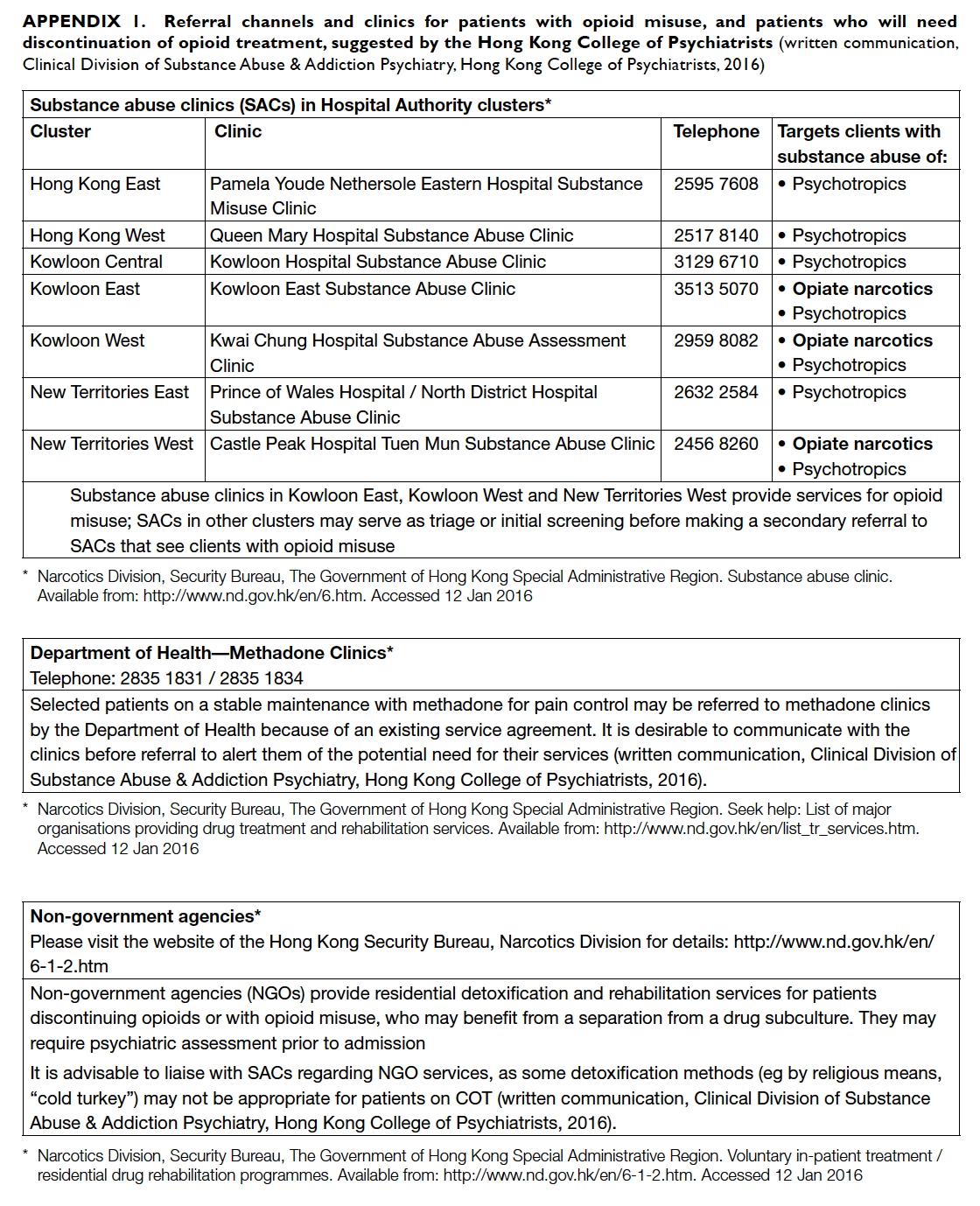

2016). Patients with active substance abuse (opioid,

non-opioid, or both) and psychological disturbances

may be referred to substance abuse clinics (SACs)

in Hong Kong for pre-COT psychiatric treatment

(Appendix 1).

Appendix 1. Referral channels and clinics for patients with opioid misuse, and patients who will need discontinuation of opioid treatment, suggested by the Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists

(written communication, Clinical Division of Substance Abuse & Addiction Psychiatry, Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists, 2016)

Recommendations

- Patients considered for COT should have a thorough physical, psychological, and social assessment.

- Risk of substance misuse or addiction should also be assessed for appropriate treatment planning.

Prescription of chronic opioids

Informed consent and documentation

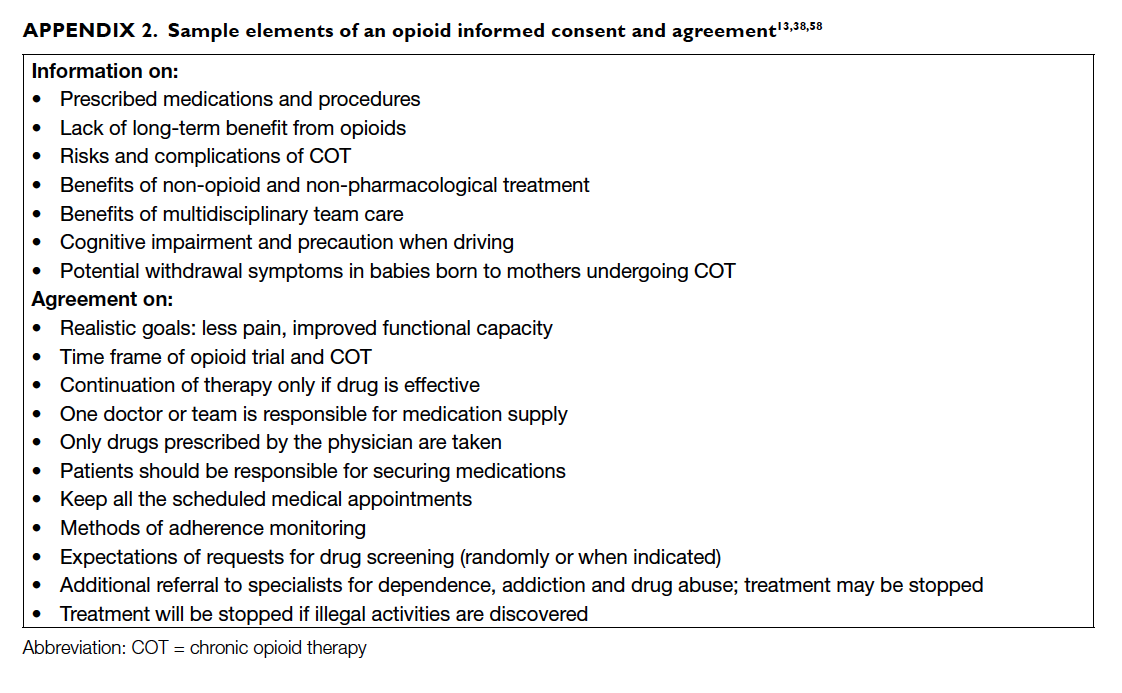

Guides on COT for CNCP recognise the need for

informed consent to explain the benefits, risks,

and complications of COT before a trial of opioid

therapy, and when the decision to use COT is

reached.38 46 Consent in the form of a written plan or treatment agreement, or opioid contract, can

set expectations between the physician and patient

regarding their actions and treatment targets.13 38 46

The usefulness of a contract in promoting adherence

to a COT regimen lacks evidence, however. Also,

use of a contract has underlying ethical issues

relating to patient autonomy and the assumption of

potential opioid abuse.13 58 Nevertheless, if utilised, an agreement should outline information on COT

and alternative treatment options, benefits, risks

(which include adverse effects, behavioural risks,

and medical complications), steps to reach treatment

goals, means of monitoring improvements, and

conditions for continuing or discontinuing therapy

(Appendix 2).13 38 58 Specifically, it may include from whom and where the patients should obtain

their prescription, the number and time of office

follow-ups, and expectations on use of UDS.46 58 The agreement should be reviewed continually during

treatment.46

Trial of opioid therapy

An opioid trial assesses patients’ responsiveness

to opioids. Dose titration during an opioid trial

determines the lowest effective dose with the least

or minimal side-effects for an individually tailored

programme.59 The choice of opioid should be based

on factors related to the individual patient, such as

previous response to opioids, health status, treatment

goals, predicted risks; on medication-related factors,

such as availability and pharmacological and adverse

effect profiles; and on physician experience and

expertise.33 36 59 Parenteral forms of opioids are not

recommended for an opioid trial due to risk of

abuse.33 36

Opioids should be titrated slowly, for example,

at increments of 10 to 50 mg equivalent per day

of a long-acting opioid, until the optimal dose

that provides benefit with the least side-effects is

attained.33 47 60 The optimal dose is suggested to lead

to a 30% pain reduction (based on an 11-point scale)

that does not cause significant adverse effects.33 61 A trial of therapy may last weeks or months. Duration

can be set from 4 to 6 weeks, or up to 90 days in some

pain centres.46 47 60 The target results and duration of

the trial period should be understood and agreed by

the patient.46 60

Prescription for special concerns

Driving and work safety are potential concerns when

COT is used. Studies have not shown impairment

of driving-related activities with opioids,13 62 63 but

patients should be informed of factors related to

opioid use that may cause impairment, including

initiating opioids or changing opioid dose, poor

sleep, severe pain, and concomitant intake of

alcohol or sedating medications.13 33 38 Patients

should be advised to avoid driving or participating

in potentially dangerous activities if they show signs

of impaired cognition or psychomotor ability, such

as somnolence, poor coordination, or decreased

concentration.33 38

Pregnant patients or patients planning to get

pregnant should be counselled on the risks of COT

during pregnancy. Such therapy during pregnancy

has been found to be associated with neonatal

withdrawal syndrome, poor birth outcome, and

certain birth defects.64 65 66 Because of this, COT during

pregnancy is not encouraged unless the potential

benefits outweigh the risks.38 47

Recommendations

- Informed consent should be obtained before an opioid trial as well as before the start of COT.

- Prior to COT, an opioid trial should be conducted to assess patient response and to determine an optimal opioid dose.

- The choice of drugs and initial dosing should be individualised according to the drug profile, patient characteristics and goals, and physician experience.

- Patients on opioids who show signs of impaired cognition or psychomotor activity should be cautioned against driving and other potentially dangerous activities.

- Use of COT during pregnancy is discouraged because opioids may lead to poor birth outcomes.

Monitoring during chronic opioid therapy

Ongoing assessment and regular monitoring during

COT allows physicians to characterise patients who

continue to benefit from opioids or who may need

changes in their treatment programme. During

an opioid trial, the patient is regularly monitored,

usually at weekly intervals, to assess the four A’s:

analgesia, activity, adverse effects, and aberrant

behaviour.33 60 67 The dose is adjusted based on

changes in pain intensity, improvements in daily

function, and development of side-effects and of

aberrant behaviour.33 35 46 Validated pain assessment

tools such as the Brief Pain Inventory or the Pain,

Enjoyment, and General Activity scale may be used

at baseline and at regular intervals thereafter to

describe changes in pain relief and function.33 46 47

Drug-related behaviour can be monitored through

patient interviews, observation, and UDS.

Evidence is lacking on the reliability of UDS in

predicting aberrant behaviour, and UDS still needs

to be evaluated if it improves clinical outcomes.37

Nonetheless, UDS provides important information

on adherence to the treatment plan and existence

of possible drug misuse when appropriately used

with other monitoring tools. Although other

biological specimens may be tested, obtaining

urine is considered practical and convenient, and

results can be obtained within a few days to allow

modification of patient care.68 Physicians should

be aware of limitations in interpreting results

and should maintain communication with testing

laboratories to resolve any doubts.68 In addition,

differential diagnoses for each result should be

considered, for example, absence of prescribed drug

in the urine could indicate non-access to required

prescription, or diversion of the prescription.37 69 These considerations should facilitate a discussion

with the patient in order to improve care. Prior to

the onset of opioid therapy, it is important to educate

the patient and specify the objectives of UDS in the

treatment agreement to avoid confrontation and

uphold a strong physician-patient relationship.69

There is no agreement on the frequency of UDS, but it should be performed as frequently

as necessary according to the patient’s risk for

misuse, occurrence of aberrant behaviour, and on

availability of the test.37 47 If aberrant drug behaviour is noticed, the patient may need more intensive

monitoring and referral to a pain or substance abuse

specialist.47 60 Continuation of opioid therapy may be agreed upon by physician and patient if there is note

of progress towards the patient’s goals as determined

from regular monitoring.60 If the patient is deemed

suitable to continue opioids in the long term after an

opioid trial has established a stable dose, monitoring

of the four A’s is undertaken at regular intervals.60

Intervals can be as far apart as 6 months for patients

with no risk issues, or as frequent as monthly for

those at risk of opioid misuse, or those taking doses

near the threshold level.47

Recommendations

- Monitoring during COT should include documentation of pain intensity, level of functioning, presence of adverse events, and adherence to prescribed therapies.

- Validated pain assessment tools may be used at baseline and regularly thereafter to describe changes in pain and function.

Opioid rotation

Patients who initially responded but have become

tolerant despite escalating doses, and those in whom

side-effects limit dose increases, may consider

an opioid switch or rotation.70 Despite the lack of

evidence from controlled studies for the clinical

effectiveness of opioid rotation,71 72 the strategy may be useful based on observed differences in individual

responses to various opioids.73 This occurrence

may be explained by genetic variations in receptor

subtypes that modulate drug effects, and that also

potentially promote incomplete cross-tolerance

among opioids.74

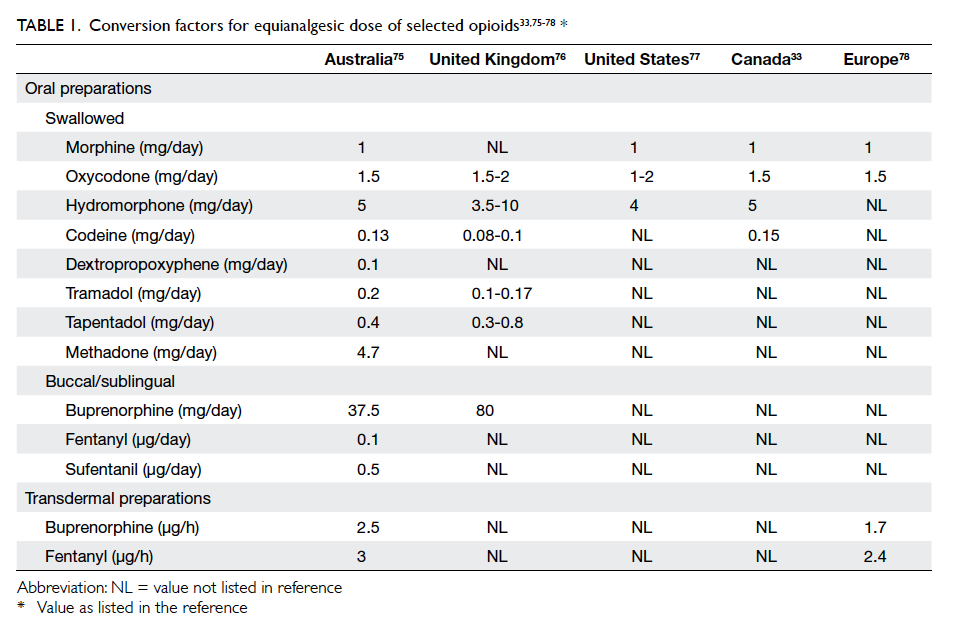

Opioid rotation involves selection of a new

opioid, determination of its appropriate initial dose,

and subsequent titration for a satisfactory balance of

efficacy and side-effects.70 Use of an equianalgesic

table can facilitate estimation of the new drug’s

initial dose.33 75 76 77 78 Its dose should approximate the dose of the previous drug (Table 133 75 76 77 78). Drug

potencies reflected by the reference table may be

underestimated74; therefore, experts support an initial

automatic reduction in the estimated equianalgesic

dose of the new drug by 25% to 50% for safety.70 If the

previous dose was high, a reduction by at least 50% is

recommended by some authors.33 Exceptions to this

include a switch to methadone, which should use a

reduction of 75% to 90%, and switch to transdermal

fentanyl, which does not require a reduction.70 This

initial computation should be adjusted or retained

based on the patient’s clinical situation. Subsequent

drug titration should be based on this initial dose.70

Recommendations

- When switching to a new opioid, calculate the equianalgesic dose using a reference equianalgesic table.

- Reduction of the calculated dose is recommended for safety.

- Prior to a new opioid trial, adjust the dose further after reassessment of the patient’s clinical situation.

Management of side-effects and problematic opioid use

Constipation, nausea, headache, and sedation are

the most frequently reported opioid side-effects

in clinical trials.12 Many side-effects reportedly

diminish over time,12 but some side-effects such as

constipation and vomiting may be severe enough to

prompt discontinuation from trials. Constipation, in

particular, may not diminish and cause significant

severe discomfort.79 Opioid dose adjustment, opioid

rotation, and proactive therapy (eg stool softeners

for constipation) are strategies that can minimise

severity of adverse effects.21 79 Common opioid-associated side-effects should be anticipated and

managed appropriately when identified to maintain

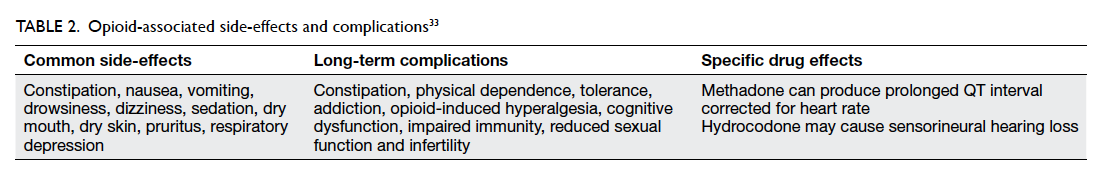

compliance (Table 2).33

Problematic drug use or aberrant drug

behaviour may arise from opioid use. As described

previously, patients on COT who are at high

risk of opioid misuse or addiction may need

additional consultation with addiction experts,

and a restructuring of their programme to include

frequent, close monitoring.33 46 47 54 In addition

to patient interviews, proper drug use may be

monitored through methods such as regular visits,

pill counts, and UDS.80 Physicians should attempt

to identify the cause of behaviour that suggests

the possibility of opioid misuse. It is important to

be aware of pseudo-addiction, which apparently

exhibits the same compulsive behaviours for opioids

as in addiction, but is due to inadequate pain relief

from undermedication.81

When drug misuse is identified, the patient

should undergo a complete re-evaluation for

treatment modification.33 Repeated, serious

aberrant behaviour requires discontinuation of

COT and referral to substance abuse specialists

for detoxification.33 47 Referral channels and treatment through SACs for patients with significant

psychological disturbance or addiction features (eg

aberrant drug behaviour, other substance abuse such

as benzodiazepines) are available in Hong Kong

(Appendix 1).

Recommendations

- Anticipate common side-effects and manage appropriately.

- If problematic drug use is recognised, re-evaluate the patient and modify treatment.

- Discontinue COT if aberrant behaviour is present. Referral to substance abuse specialists is warranted.

Upper dose limit and exit strategy

The goals of COT should be revisited at regular

intervals to see if patients can meet their targets

within a defined dose range, determined from the

initial daily dose titrated to the lowest effective dose.

It is recommended that the upper dose titration

limit should not exceed 120 mg of oral morphine or

its equivalent, or 200 mg in some centres.33 38 47 60 If

the daily dose exceeds this limit, a reassessment of

the pain condition, potential for misuse, and need

for more frequent monitoring is warranted.33 38 Indications for discontinuation include no change or

improvement in therapeutic goals despite escalating

doses, intolerance to side-effects, and persistence of

aberrant behaviour. If the decision to discontinue

opioids is reached, the opioid should be tapered to

avoid withdrawal problems.33 46 47 60

The tapering plan is variable, but generally, a

reduction of 10% per week from the original dose

is well tolerated.33 47 60 A faster or slower rate may

be suitable depending on the patient’s situation.

Physicians should monitor patients for changes

in pain and for the appearance of side-effects,

withdrawal symptoms, and behavioural issues. These

concerns should be properly managed. In some

cases, a referral to the appropriate specialists may

be warranted. Likewise, patients who fail to benefit

from COT and who need discontinuation may be

referred to SACs in Hong Kong for detoxification

and rehabilitation services (written communication,

Clinical Division of Substance Abuse & Addiction

Psychiatry, Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists,

2016).

Recommendations

- Chronic opioid therapy should be stopped if patients experience no progress towards treatment goals, experience intolerable side-effects, or are engaged in repeated aberrant drug-related behaviours.

- Opioids should be tapered to avoid withdrawal.

Conclusion

Strong opioids play a role in the multimodal

management of CNCP. They may be appropriate

for selected patients despite insufficient evidence

of effectiveness. Opioid therapy is potentially

associated with common side-effects and significant

harm; thus, careful patient selection by a thorough

patient evaluation prior to treatment, and careful

dose titration and monitoring during initiation and

long-term therapy, are all recommended steps for

rational opioid use in CNCP. Whenever opioid is

prescribed for chronic pain management, it should

be started with a low dose and titrated slowly, as well

as maintained for the shortest possible time.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Clinical Division of

Substance Abuse & Addiction Psychiatry, Hong

Kong College of Psychiatrists for their advice and

opinions.

Declaration

All authors are members of the working group

for Guideline for Chronic Opioid Therapy in

Chronic Noncancer Pain, Hospital Authority

Multidisciplinary Committee on Pain Medicine,

Hospital Authority, Hong Kong. All authors have

disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Merskey H, Bogduk N, editors. International Association

for the Study of Pain. Task Force on Taxonomy.

Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain

syndromes and definitions of pain terms. 2nd ed. Seattle:

IASP Press; 2002.

2. Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC.

The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific

advances and future directions. Psychol Bull 2007;133:581-624. Crossref

3. Ng KF, Tsui SL, Chan WS. Prevalence of common chronic

pain in Hong Kong adults. Clin J Pain 2002;18:275-81. Crossref

4. Wong WS, Fielding R. Prevalence and characteristics of

chronic pain in the general population of Hong Kong. J

Pain 2011;12:236-45. Crossref

5. Vallejo R, Barkin RL, Wang VC. Pharmacology of opioids

in the treatment of chronic pain syndromes. Pain Physician

2011;14:E343-60.

6. World Health Organization. WHO’s cancer pain ladder

for adults. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/. Accessed 28 Jul 2015.

7. Manchikanti L, Vallejo R, Manchikanti KN, Benyamin

RM, Datta S, Christo PJ. Effectiveness of long-term opioid

therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain Physician

2011;14:E133-56.

8. Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness

and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain:

a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health

Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med

2015;162:276-86. Crossref

9. Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Opioids in

chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and

safety. Pain 2004;112:372-80. Crossref

10. Furlan AD, Sandoval JA, Mailis-Gagnon A, Tunks E.

Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a meta-analysis of

effectiveness and side effects. CMAJ 2006;174:1589-94. Crossref

11. Papaleontiou M, Henderson CR Jr, Turner BJ, et al.

Outcomes associated with opioid use in the treatment of

chronic noncancer pain in older adults: a systematic review

and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1353-69. Crossref

12. Noble M, Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, et al. Long-term opioid

management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2010;(1):CD006605. Crossref

13. Chan BK, Tam LK, Wat CY, Chung YF, Tsui SL, Cheung

CW. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain. Expert Opin

Pharmacother 2011;12:705-20. Crossref

14. Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Prevalence of opioid adverse

events in chronic non-malignant pain: systematic review

of randomised trials of oral opioids. Arthritis Res Ther

2005;7:R1046-51. Crossref

15. Noble M, Tregear SJ, Treadwell JR, Schoelles K. Long-term

opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain: a systematic

review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety. J Pain

Symptom Manage 2008;35:214-28. Crossref

16. Dhalla IA, Mamdani MM, Sivilotti ML, Kopp A, Qureshi

O, Juurlink DN. Prescribing of opioid analgesics and related

mortality before and after the introduction of long-acting

oxycodone. CMAJ 2009;181:891-6. Crossref

17. Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J

Med 2010;363:1981-5. Crossref

18. Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Russo JE, DeVries A, Braden JB,

Sullivan MD. The role of opioid prescription in incident

opioid abuse and dependence among individuals with

chronic noncancer pain: the role of opioid prescription.

Clin J Pain 2014;30:557-64.

19. Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Fracture risk

associated with the use of morphine and opiates. J Intern

Med 2006;260:76-87. Crossref

20. Smith HS, Elliott JA. Opioid-induced androgen deficiency

(OPIAD). Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl):ES145-56.

21. Inturrisi CE. Clinical pharmacology of opioids for pain.

Clin J Pain 2002;18(4 Suppl):3S-13S. Crossref

22. Ersek M, Cherrier MM, Overman SS, Irving GA. The

cognitive effects of opioids. Pain Manag Nurs 2004;5:75-93. Crossref

23. Roy S, Loh HH. Effects of opioids on the immune system.

Neurochem Res 1996;21:1375-86. Crossref

24. Lee M, Silverman SM, Hansen H, Patel VB, Manchikanti L.

A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia.

Pain Physician 2011;14:145-61.

25. Tompkins DA, Campbell CM. Opioid-induced

hyperalgesia: clinically relevant or extraneous research

phenomenon? Curr Pain Headache Rep 2011;15:129-36. Crossref

26. Pain & Policy Studies Group. Global opioid consumption,

2013. Available from: http://www.painpolicy.wisc.edu/global. Accessed 1 Aug 2015.

27. Pain & Policy Studies Group. Opioid consumption maps—Morphine equivalence (ME), mg/capita, 2014. Available

from: https://ppsg.medicine.wisc.edu. Accessed 11 Oct

2015.

28. Pain & Policy Studies Group. Consumption data at-a-glance:

Hong Kong SAR, 2012. Available from: http://www.painpolicy.wisc.edu/country/profile/hong-kong-sar.

Accessed 1 Aug 2015.

29. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug

Report 2008. Available from: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/WDR-2008.html. Accessed 7

Jan 2016.

30. Drug Office, Department of Health, The Government of

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Registered pharmaceutical products. Available from: http://www.drugoffice.gov.hk/eps/do/en/consumer/reg_pharm_products/index.html. Accessed 11 Oct 2015.

31. Ho KY, Chua NH, George JM, et al. Evidence-based

guidelines on the use of opioids in chronic non-cancer

pain—a consensus statement by the Pain Association

of Singapore Task Force. Ann Acad Med Singapore

2013;42:138-52.

32. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. American Society

of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for

responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain:

Part 2—guidance. Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl):67S-116S.

33. Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for

chronic non-cancer pain. Canada: National Opioid Use

Guideline Group (NOUGG); 2010. Available from: http://nationalpaincentre.mcmaster.ca/opioid/. Accessed 9 Aug

2016.

34. American College of Occupational and Environmental

Medicine. Guidelines for chronic use of opioids. Available

from: http://www.acoem.org/Guidelines_Opioids.aspx.

Accessed 25 Nov 2014.

35. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists

Faculty of Pain Medicine. Recommendations regarding

the use of opioid analgesics in patients with chronic

non-cancer pain. Available from: http://www.fpm.anzca.edu.au/resources/professional-documents/documents/PM1%202010.pdf. Accessed 25 Nov 2014.

36. British Pain Society. Opioids aware: A structured approach

to prescribing. Faculty of Pain Medicine, Royal College of Anaesthetists. Available from: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/faculty-of-pain-medicine/opioids-aware/structured-approach-to-prescribing. Accessed 9 Aug 2016.

37. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for

the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain

2009;10:113-30. Crossref

38. Cheung CW, Qiu Q, Choi SW, Moore B, Goucke R, Irwin

M. Chronic opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain:

a review and comparison of treatment guidelines. Pain

Physician 2014;17:401-14.

39. Von Korff M, Saunders K, Thomas Ray G, et al. De facto

long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain. Clin J Pain

2008;24:521-7. Crossref

40. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain

treatment services. Available from: http://www.iasppain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1381.

Accessed 9 Sep 2015.

41. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B.

Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present,

and future. Am Psychol 2014;69:119-30. Crossref

42. Jeffrey MM, Butler M, Stark A, Kane RL. Multidisciplinary

pain programs for chronic noncancer pain: Technical brief

No. 8. AHRQ Publication No. 11-EHC064-EF. Rockville,

MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Sep

2011. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK82511/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK82511.pdf. Accessed 9

Aug 2016.

43. Gatchel RJ, Okifuji A. Evidence-based scientific data

documenting the treatment and cost-effectiveness of

comprehensive pain programs for chronic nonmalignant

pain. J Pain 2006;7:779-93. Crossref

44. Guzmán J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Irvin E,

Bombardier C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic

low back pain: systematic review. BMJ 2001;322:1511-6. Crossref

45. Turk DC. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

of treatments for patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain

2002;18:355-65. Crossref

46. Federation of State Medical Boards. Model policy on the

use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of chronic pain,

July 2013. Available from: http://www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/pain_policy_july2013.pdf.

Accessed 9 Aug 2016.

47. Agency Medical Directors’ Group. AMDG 2015

Interagency guidelines on prescribing opioids for pain.

Available from: http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/guidelines.asp. Accessed 11 Aug 2015.

48. Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Revicki D, et al. Identifying

important outcome domains for chronic pain clinical

trials: an IMMPACT survey of people with pain. Pain

2008;137:276-85. Crossref

49. Lee D, Armaghani S, Archer KR, et al. Preoperative opioid

use as a predictor of adverse postoperative self-reported

outcomes in patients undergoing spine surgery. J Bone

Joint Surg Am 2014;96:e89. Crossref

50. Armaghani SJ, Lee DS, Bible JE, et al. Preoperative

opioid use and its association with perioperative opioid

demand and postoperative opioid independence in

patients undergoing spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)

2014;39:E1524-30. Crossref

51. Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J, Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS.

What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients

exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop

abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors?

A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med 2008;9:444-59. Crossref

52. Morasco BJ, Gritzner S, Lewis L, Oldham R, Turk DC,

Dobscha SK. Systematic review of prevalence, correlates,

and treatment outcomes for chronic non-cancer pain

in patients with comorbid substance use disorder. Pain

2011;152:488-97. Crossref

53. Højsted J, Sjøgren P. Addiction to opioids in chronic pain patients: a literature review. Eur J Pain 2007;11:490-518. Crossref

54. Atluri S, Akbik H, Sudarshan G. Prevention of opioid abuse

in chronic non-cancer pain: an algorithmic, evidence based

approach. Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl):ES177-89.

55. Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Hudson T, Harris KM, Sullivan M.

Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and

dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic

non-cancer pain. Pain 2007;129:355-62. Crossref

56. Turk DC, Swanson KS, Gatchel RJ. Predicting opioid

misuse by chronic pain patients: a systematic review and

literature synthesis. Clin J Pain 2008;24:497-508. Crossref

57. Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors

in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the

Opioid Risk Tool. Pain Med 2005;6:432-42. Crossref

58. Arnold RM, Han PK, Seltzer D. Opioid contracts in

chronic nonmalignant pain management: objectives and

uncertainties. Am J Med 2006;119:292-6. Crossref

59. Geppetti P, Benemei S. Pain treatment with opioids:

achieving the minimal effective and the minimal interacting

dose. Clin Drug Investig 2009;29 Suppl 1:3S-16S. Crossref

60. Department of Health, Government of Western Australia.

Quick clinical guideline for the use of opioids in chronic

non-malignant pain. Available from: http://www.hnehealth.nsw.gov.au/Pain/Pages/Health-professional-resources.aspx. Accessed 28 Jul 2015.

61. Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM.

Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity

measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain

2001;94:149-58. Crossref

62. Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. Are

opioid-dependent/tolerant patients impaired in driving-related

skills? A structured evidence-based review. J Pain

Symptom Manage 2003;25:559-77. Crossref

63. Engeland A, Skurtveit S, Mørland J. Risk of road traffic

accidents associated with the prescription of drugs: a

registry-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:597-602. Crossref

64. Hadi I, da Silva O, Natale R, Boyd D, Morley-Forster PK.

Opioids in the parturient with chronic nonmalignant pain:

a retrospective review. J Opioid Manag 2006;2:31-4.

65. Broussard CS, Rasmussen SA, Reefhuis J, et al. Maternal

treatment with opioid analgesics and risk for birth defects.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:314.e1-11. Crossref

66. Fajemirokun-Odudeyi O, Sinha C, Tutty S, et al. Pregnancy

outcome in women who use opiates. Eur J Obstet Gynecol

Reprod Biol 2006;126:170-5. Crossref

67. Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Whitcomb L, et al. A new tool to

assess and document pain outcomes in chronic pain

patients receiving opioid therapy. Clin Ther 2004;26:552-61. Crossref

68. Gourlay DL, Heit HA, Caplan YH. Urine drug testing in

clinical practice: the art and science of patient care. 6th ed. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University School

of Medicine; Aug 2015. Available from: http://www.udtmonograph6.com/view-monograph.html. Accessed 23 Aug

2016.

69. Peppin JF, Passik SD, Couto JE, et al. Recommendations for

urine drug monitoring as a component of opioid therapy in

the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Med 2012;13:886-96. Crossref

70. Fine PG, Portenoy RK, Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence

Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation. Establishing

“best practices” for opioid rotation: conclusions of an

expert panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:418-25. Crossref

71. Quigley C. Opioid switching to improve pain relief

and drug tolerability. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2004;(3):CD004847. Crossref

72. Mercadante S, Bruera E. Opioid switching: a systematic

and critical review. Cancer Treat Rev 2006;32:304-15. Crossref

73. Pasternak GW. Molecular biology of opioid analgesia. J

Pain Symptom Manage 2005;29(5 Suppl):2S-9S. Crossref

74. Knotkova H, Fine PG, Portenoy RK. Opioid rotation: the

science and the limitations of the equianalgesic dose table.

J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:426-39. Crossref

75. Nielsen S, Degenhardt L, Hoban B, Gisev N. Comparing

opioids: a guide to estimating oral morphine equivalents

(OME) in research. Technical Report No. 329. Sydney:

National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University

of New South Wales; 2014. Available from: https://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/resource/comparing-opioids-guide-estimating-oral-morphine-equivalents-ome-research.

Accessed 24 Mar 2016.

76. UK Medicines Information (UKMi). Medicines Q&As:

Q&A 42.7: What are the equivalent doses of oral morphine

to other oral opioids when used as analgesics in adult

palliative care? Available from: http://www.ukmi.nhs.uk/activities/medicinesQAs/default.asp. Accessed 24 Mar

2016.

77. Lexicomp. Drug information handbook: a clinically

relevant resource for all healthcare professionals. 23rd ed.

Ohio: Lexicomp; 2014.

78. Mercadante S, Caraceni A. Conversion ratios for opioid

switching in the treatment of cancer pain: a systematic

review. Palliat Med 2011;25:504-15. Crossref

79. Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid

complications and side effects. Pain Physician 2008;11(2

Suppl):105S-120S.

80. Sehgal N, Manchikanti L, Smith HS. Prescription opioid

abuse in chronic pain: a review of opioid abuse predictors

and strategies to curb opioid abuse. Pain Physician

2012;15(3 Suppl):ES67-92.

81. Weissman DE, Haddox JD. Opioid pseudoaddiction—an iatrogenic syndrome. Pain 1989;36:363-6. Crossref