Hong Kong Med J 2016 Oct;22(5):472–7 | Epub 26 Aug 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164897

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Management of health care workers following occupational exposure to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus

Winnie WY Sin, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine);

Ada WC Lin, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine);

Kenny CW Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine);

KH Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)

Special Preventive Programme, Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Kowloon Bay Health Centre, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Kenny CW Chan (kcwchan@dh.gov.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Needlestick injury or mucosal contact

with blood or body fluids is well recognised in the

health care setting. This study aimed to describe

the post-exposure management and outcome in

health care workers following exposure to hepatitis

B, hepatitis C, or human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV) during needlestick injury or mucosal contact.

Methods: This case series study was conducted

in a public clinic in Hong Kong. All health care

workers with a needlestick injury or mucosal contact

with blood or body fluids who were referred to the

Therapeutic Prevention Clinic of Department of

Health from 1999 to 2013 were included.

Results: A total of 1525 health care workers were

referred to the Therapeutic Prevention Clinic

following occupational exposure. Most sustained a

percutaneous injury (89%), in particular during post-procedure

cleaning or tidying up. Gloves were worn

in 62.7% of instances. The source patient could be

identified in 83.7% of cases, but the infection status

was usually unknown, with baseline positivity rates

of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV of all identified

sources, as reported by the injured, being 7.4%, 1.6%,

and 3.3%, respectively. Post-exposure prophylaxis

of HIV was prescribed to 48 health care workers, of

whom 14 (38.9%) had been exposed to known HIV-infected blood or body fluids. The majority (89.6%)

received HIV post-exposure prophylaxis within 24

hours of exposure. Drug-related adverse events were

encountered by 88.6%. The completion rate of post-exposure

prophylaxis was 73.1%. After a follow-up

period of 6 months (or 1 year for those who had taken

HIV post-exposure prophylaxis), no hepatitis B,

hepatitis C, or HIV seroconversions were detected.

Conclusions: Percutaneous injury in the health

care setting is not uncommon but post-exposure

prophylaxis of HIV is infrequently indicated. There

was no hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV transmission

via sharps or mucosal injury in this cohort of health

care workers.

New knowledge added by this study

- The risk of hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission following occupational sharps or mucosal injury in Hong Kong is small.

- Meticulous adherence to infection control procedures and timely post-exposure management prevents HBV, HCV, and HIV infection following occupational exposure to blood and body fluids.

Introduction

Needlestick injury or mucosal contact with blood

or body fluids is well recognised in the health care

setting. These incidents pose a small but definite risk

for health care workers of acquiring blood-borne

viruses, notably hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis

C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV). The estimated risk of contracting HBV

infection through occupational exposure to known

infected blood via needlestick injury varies from 18%

to 30%, while that for HCV infection is 1.8% (range,

0%-7%).1 The risk of HIV transmission following

percutaneous or mucosal exposure to HIV-contaminated

blood is 0.3% and 0.09%, respectively.1

The risk is further affected by the type of exposure,

body fluid involved, and infectivity of the source.

In Hong Kong, injured health care workers

usually receive initial first aid and immediate

management in the Accident and Emergency

Department. They are then referred to designated

clinics for specific post-exposure management.

Currently, aside from staff of the Hospital Authority

who are managed at two designated clinics post-exposure,

all other health care workers from

private hospitals, and government or private clinics

and laboratories are referred to the Therapeutic

Prevention Clinic (TPC) of the Integrated Treatment

Centre, Department of Health. Since its launch in

mid-1999, the TPC has provided comprehensive

post-exposure management to people with

documented percutaneous, mucosal, or breached

skin exposure to blood or body fluids in accordance

with the local guidelines set out by the Scientific

Committee on AIDS and STI, and Infection Control

Branch of Centre for Health Protection, Department

of Health.2 The present study describes the characteristics

and outcome of health care workers who attended the

TPC from mid-1999 to 2013 following occupational

exposure to blood or body fluids.

Methods

The study included all health care workers seen in

the TPC from July 1999 to December 2013 following

occupational exposure to blood or body fluids, who

attended following secondary referral by an accident

and emergency department of a public hospital.

Using two standard questionnaires (Appendices 1 and 2), data were collected by the attending nurse and

doctor during a face-to-face interview with each

health care worker on the following: demography

and occupation of the exposed client, type and

pattern of exposure, post-exposure management,

and clinical outcome.

Appendix 1. TPC First Consultation Assessment Form

Appendix 2. Therapeutic Prevention Clinic (TPC) human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Post-exposure Prophylaxis Registry Form (to be completed on completion or cessation of post-exposure prophylaxis)

Details of the exposure, including type of

exposure and the situation in which it occurred, were

noted. The number of risk factors (see definitions

below) for HIV transmission was counted for each

exposure and further classified as high risk or low

risk. Where known and reported by the injured

party, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), HCV, and

HIV status of the source were recorded.

The timing of the first medical consultation

in the accident and emergency department, any

prescription of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis

(PEP), and the time since injury were noted.

Exposed health care workers who received HIV PEP

were reviewed at clinic visits every 2 weeks until

completion of the 4-week course of treatment, and

any treatment-related adverse effects were reported.

Blood was obtained as appropriate at these visits for

measurement of complete blood count, renal and

liver function, and amylase, creatine kinase, fasting

lipid, and glucose levels.

Apart from HIV PEP–related side-effects

(reported and rated by patients as mild, moderate, or

severe), the rate of completion of PEP, and number of

HBV, HCV, and HIV seroconversions following the

incident was also recorded. The HBsAg, anti-HBs,

anti-HCV, and anti-HIV were checked at baseline

and 6 months post-exposure to determine whether

seroconversion had occurred. Those exposed to a

known HCV-infected source or a source known to

be an injecting drug user had additional blood tests

6 weeks post-exposure for liver function, anti-HCV,

and HCV RNA. Additional HIV antibody testing at 3

and 12 months post-exposure was arranged for those

who received HIV PEP. For those who contracted

HCV infection from a source co-infected with HCV

and HIV, further HIV testing was performed at 1 year

post-exposure to detect delayed seroconversion.

Definitions

Health care workers included doctors and medical

students, dentists and dental workers, nurses,

midwives, inoculators, laboratory workers,

phlebotomists, ward or clinic attendants, and

workmen. Staff working in non–health care

institutions (eg elderly home, hostels, and sheltered

workshops) were excluded. Five factors were classified

as high-risk exposure: (i) deep percutaneous injury,

(ii) procedures involving a device placed in a blood

vessel, (iii) use of a hollow-bore needle, (iv) device that

was visibly contaminated with blood, and (iv) source

person with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

(AIDS).3 Another five factors were classified as low-risk

exposure: (i) moderate percutaneous injury,

(ii) mucosal contact, (iii) contact with deep body

fluids other than blood, (iv) source person was HIV-infected

but not or not sure about the stage of AIDS,

and (v) any other reason contributing to increased

risk according to clinical judgement.

Results

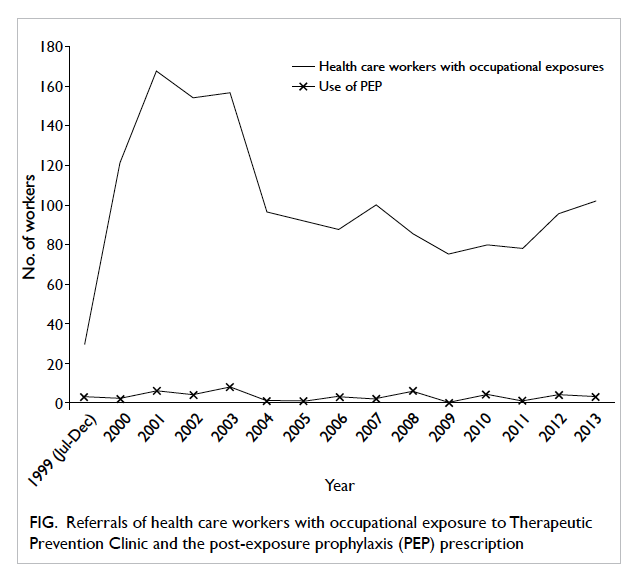

From July 1999 to December 2013, 1525 health

care workers (75-168 per year) with occupational

exposure to HBV, HCV, or HIV were referred to the

TPC (Fig). Females constituted 77% of all attendees.

The median age was 33 years (range, 17-73 years).

The majority came from the dental profession

(36.8%) and nursing profession (33.4%), followed by

ward/clinic ancillary staff (11.6%) and the medical

profession (4.7%).

Figure. Referrals of health care workers with occupational exposure to Therapeutic Prevention Clinic and the post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) prescription

Type and pattern of exposure

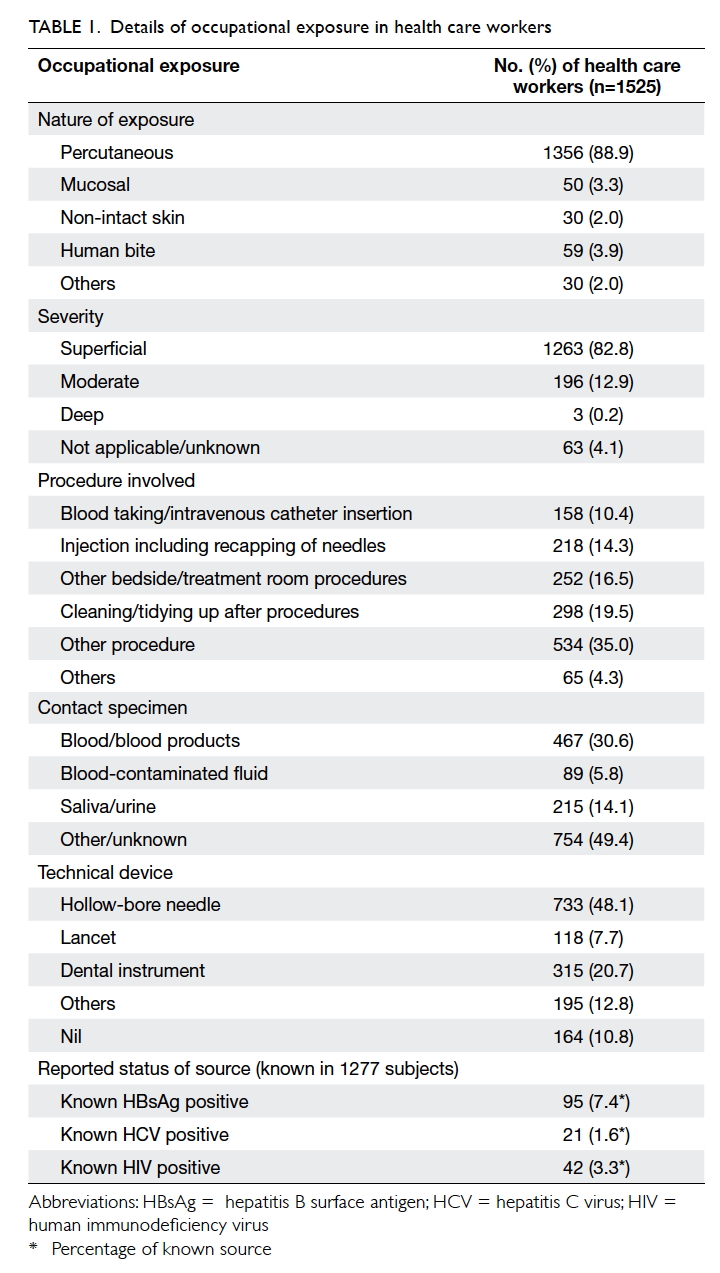

The majority of exposures occurred in a public clinic

or laboratory (n=519, 34.0%), followed by public

hospital (n=432, 28.3%), private clinic or laboratory

(n=185, 12.1%), and private hospital (n=23, 1.5%).

Most were a percutaneous injury (88.9%). Mucosal

contact, breached skin contact, and human bite

were infrequent (Table 1). Approximately 60% of the incidents occurred in one of the four situations:

(a) cleaning/tidying up after procedures (the most

common), (b) other bedside/treatment room

procedures, (c) injection, including recapping of

needles, or (d) blood taking/intravenous catheter

insertion. The contact specimen was blood or blood

products, blood-contaminated fluid, and saliva

or urine in 30.6%, 5.8%, and 14.1% of the cases,

respectively. The technical device involved was a

hollow-bore needle in 48.1%, dental instrument in

20.7%, and lancet in 7.7%. More than 80% considered

the injury superficial.

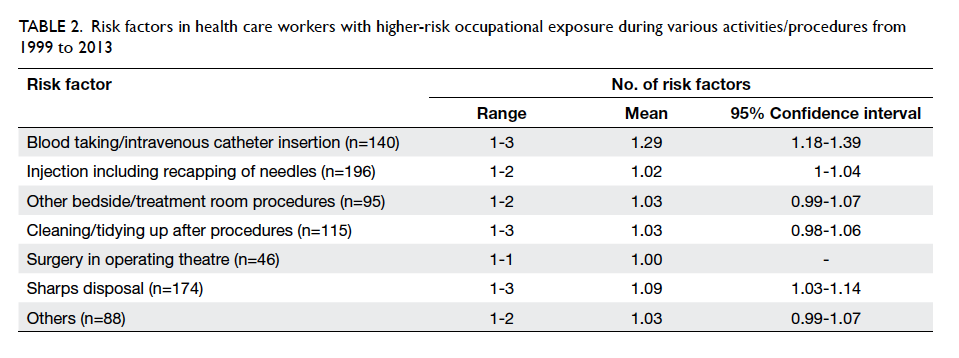

High-risk and low-risk factors were noted in

869 (57%) and 166 (11%) exposures, respectively.

Blood taking/intravenous catheter insertion carried

the highest risk among all the procedures, with a

mean risk factor of 1.29 (Table 2). Gloves were used in 956 (62.7%) exposures, goggles/mask in 50 (3.3%),

and gown/apron in 55 (3.6%). Nonetheless, 101

(6.6%) health care workers indicated that they did

not use any personal protective equipment during

the exposure.

Table 2. Risk factors in health care workers with higher-risk occupational exposure during various activities/procedures from 1999 to 2013

The source patient could be identified in 1277

(83.7%) cases but the infectious status was unknown

in most. The baseline known positivity rate for HBV,

HCV, and HIV of all identified sources was 7.4%,

1.6%, and 3.3%, respectively (Table 1).

Care and clinical outcome

Nearly half of the injured health care workers

attended a medical consultation within 2 hours

(n=720, 47.2%) and another 552 (36.2%) attended between 2 and 12 hours following

exposure. The median time between exposure and

medical consultation was 2.0 hours.

During the study period, 48 (3.1%) health

care workers received HIV PEP for occupational

exposure, ranging from zero to eight per year (Fig). One third

received PEP within 2 hours of exposure, and the

majority (89.6%) within 24 hours. The median time

to PEP was 4.0 hours post-exposure (interquartile

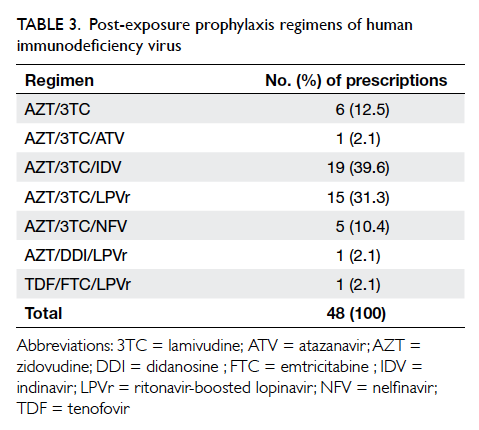

range, 2.0-8.1 hours). A three-drug regimen was

prescribed in 85.7% of cases. The most common

regimen was zidovudine/lamivudine/indinavir

(39.6%), followed by zidovudine/lamivudine/ritonavir-boosted lopinavir (31.3%), and zidovudine/lamivudine (12.5%) [Table 3]. Upon consultation and risk assessment at the TPC, 36 (75%) workers

had treatment continued from the accident and

emergency department. Among them, the source

was confirmed to be HIV-positive in 14 (38.9%) cases.

Of the 35 clients with known outcome, drug-related

adverse events were seen in 31 (88.6%) health care

workers; more than half (n=18, 58.1%) of which were

considered to be moderate or severe. Treatment-related

side-effects led to early termination of PEP

in eight (22.9%) health care workers. Excluding nine

clients in whom prophylaxis was stopped when the

source was established to be HIV-negative, 19 (73.1%)

clients were able to complete the 28-day course of

PEP. Of the 14 clients who sustained injury from an

HIV-infected source patient, all received PEP but

two did not complete the course; the completion rate

was 85.7%.

At baseline, none of the injured health care

workers tested positive for HCV or HIV, while 49

(3.2% of all health care workers seen in TPC) tested

HBsAg-positive. Almost half of the health care

workers (n=732, 48.0%) were immune to HBV (anti-HBs positive). After follow-up of 6 months (1 year

for those who took PEP), no case of HBV, HCV, or

HIV seroconversion was detected in this cohort.

Discussion

Health care workers may be exposed to blood-borne

viruses when they handle sharps and body fluids.

Thus, adherence to standard precautions of infection

control is an integral component of occupational

health and safety for health care workers. In this

cohort, percutaneous injury with sharps during

cleaning or tidying up after procedures remained

the most common mechanism of injury. Many of

these incidents could have been prevented by safer

practice, for instance, by not recapping needles or by

disposing needles directly into a sharps box after use.

The use of gloves as part of standard precautions was

suboptimal and greater emphasis on the importance

of wearing the appropriate personal protective

equipment should be made during staff training

at induction and on refresher courses. Technical

devices with safety needleless features may reduce

sharps injuries. Improvement in the system (eg

by placing a sharps box near the work area) or the

workflow to minimise distraction may also help

compliance with infection control measures.

Once exposure occurs, PEP is the last defence

against HBV and HIV. For HBV infection, PEP with

hepatitis B immunoglobulin followed by hepatitis

B vaccination has long been the standard practice

in Hong Kong. For HIV infection, the efficacy of

PEP in health care workers following occupational

exposure was demonstrated by a historic landmark

overseas case-control study.3 Prescription of

zidovudine achieved an 81% reduction in risk of HIV

seroconversion following percutaneous exposure

to HIV-infected blood.3 Local and international

guidelines now recommend a combination of three

antiretroviral drugs for PEP.2 4 5 6 In this cohort,

although more than half of the exposures had higher

risk factors for HIV acquisition, it was uncommon

for the source patients to have known HIV infection

(2.8% of these exposures). Thus, in accordance

with the local guideline, PEP was not commonly

prescribed. Nevertheless, PEP was prescribed in

all 14 exposures to a known HIV-positive source and

in other 34 exposures after risk assessment.

Our experience is comparable with the health care

service in the UK and US. In the UK, 78% of health

care workers exposed to an HIV-infected source

patient were prescribed PEP.7 In a report from the

US, only 68% of health care workers with such

exposure took PEP.8 For HCV, PEP with antiviral

therapy is not recommended according to the latest

guidelines from American Association for the Study

of Liver Diseases/Infectious Diseases Society of

America.9 In case seroconversion occurs and early

treatment is considered desirable, these patients with

acute hepatitis C can be treated with direct-acting

antivirals using the same regimen recommended for

chronic hepatitis C.

If indicated, HIV PEP should be taken as

early as possible after exposure to achieve maximal

effect. Initiation of PEP after 72 hours of exposure

was shown to be ineffective in animal studies.10 The

timing of PEP initiation in our cohort appeared to

be less prompt (33.3% within 2 hours compared with

more than 60% and 80% within 3 hours in the UK and

US, respectively). Overall, however, 89.6% managed

to start PEP within 24 hours, in line with experience

in the UK or US. Health care workers should be

reminded about post-exposure management and

the need for timely medical assessment following

occupational exposure. In the accident and

emergency department, priority assessment should

be given to health care workers exposed to blood-borne

viruses. The median duration of PEP intake of

28 days was in line with the local guidelines. With

the availability of newer drugs with fewer toxicities,

the tolerance and compliance rate should improve.

Finally, using the estimated risk of HIV

transmission with percutaneous injury of 0.3%, we

would expect four HIV seroconversions in 1356

percutaneous exposures in TPC if all were exposed

to HIV-infected blood. Because in most of these

exposures the source HIV status was unknown and

likely negative in this region of overall low HIV

prevalence (approximately 0.1%11), the actual risk

of HIV transmission was much lower in the health

care setting of Hong Kong. This finding is confirmed by the fact that no HIV seroconversion occurred in this cohort. In addition, those with exposure of the highest

risk received HIV PEP. In the UK, there were 4381

significant occupational exposures from 2002 to 2011,

of which 1336 were exposures to HIV-infected blood

or body fluid. No HIV seroconversions occurred

among these exposures.7 In the US, there has been

one confirmed case of occupational transmission of

HIV in health care workers since 1999.12 Similarly,

the local prevalence of HCV infection is low

(<0.1% in new blood donors13), partly explaining

the absence of HCV transmission in this cohort. In

contrast, there were 20 cases of HCV seroconversion

in health care workers reported between 1997 and

2011 in the UK.7 Hepatitis B is considered to be

endemic in Hong Kong, with HBsAg positivity of

1.1% in new blood donors and 6.5% in antenatal

women in 2013.13 Nonetheless, the HBV vaccination

programme in health care workers coupled with

HBV PEP has proven successful in preventing

HBV transmission to health care workers. With

concerted efforts in infection control and timely PEP,

transmission of blood-borne viruses via sharps and

mucosal injury in the health care setting is largely

preventable.

There are several limitations to our study.

First, data were collected from a single centre and

based on secondary referral. We did not have data

for other health care workers who had occupational

exposure but who were not referred to the TPC for

post-exposure management, or who were referred

but did not attend. Thus, we were not able to draw

any general conclusions on the true magnitude of

the problem. Second, details of the exposure and

the infection status of the source were self-reported

by the exposed client and prone to bias and under-reporting.

Conclusions

Percutaneous injury with sharps during cleaning or

tidying up after procedures was the most common

cause of occupational exposure to blood or body

fluids in this cohort of health care workers. The

majority of source patients were not confirmed HIV-positive

and HIV PEP was not generally indicated.

Prescriptions of HIV PEP were appropriate and

timely in most cases. There were no HIV, HBV, and

HCV seroconversions in health care workers who

attended the TPC following sharps or mucosal injury

from mid-1999 to 2013.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Pruss-Ustun A, Rapiti E, Hutin Y. Sharps injuries: Global

burden of disease from sharps injuries to health-care

workers (World Health Organization Environmental

Burden of Disease Series, No. 3). Available from: http://www.who.int/quantifying_ehimpacts/publications/en/sharps.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 2 Feb 2016.

2. Scientific Committee on AIDS and STI (SCAS), and

Infection Control Branch, Centre for Health Protection,

Department of Health. Recommendations on the

management and postexposure prophylaxis of needlestick

injury or mucosal contact to HBV, HCV and HIV. Hong

Kong: Department of Health; 2014.

3. Cardo DM, Culver DH, Ciesielski CA, et al. A case-control

study of HIV seroconversion in health care workers after

percutaneous exposure. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention Needlestick Surveillance Group. N Engl J Med

1997;337:1485-90. Crossref

4. Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA, et al. Updated

US Public Health Service guidelines for the management

of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency

virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013;34:875-92. Crossref

5. UK Department of Health. HIV post-exposure prophylaxis:

guidance from the UK Chief Medical Officers’ Expert

Advisory Group on AIDS. 19 September 2008 (last updated

29 April 2015).

6. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review

Committee. Guidelines on Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

for HIV and the Use of Co-Trimoxazole Prophylaxis for

HIV-Related Infections Among Adults, Adolescents and

Children: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach:

December 2014 supplement to the 2013 consolidated

guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating

and preventing HIV infection. Geneva: World Health

Organization; December 2014.

7. Eye of the Needle. United Kingdom surveillance of

significant occupational exposures to bloodborne viruses

in healthcare workers. London: Health Protection Agency;

December 2012.

8. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention. The National Surveillance

System for Healthcare Workers (NaSH): Summary report

for blood and body fluid exposure data collected from

participating healthcare facilities (June 1995 through

December 2007).

9. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases/Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV guidance:

recommendations for testing, managing, and treating

hepatitis C (updated 24 February 2016). Available from:

http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed 5 May 2016.

10. Tsai CC, Emau P, Follis KE, et al. Effectiveness of

postinoculation (R)-9-(2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)

adenine treatment for prevention of persistent simian

immunodeficiency virus SIVmne infection depends

critically on timing of initiation and duration of treatment.

J Virol 1998;72:4265-73.

11. HIV surveillance report—2014 update. Department

of Health, The Government of the Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region; December 2015.

12. Joyce MP, Kuhar D, Brooks JT, Occupationally acquired

HIV infection among health care workers—United States,

1985-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;63:1245-6.

13. Surveillance of viral hepatitis in Hong Kong—2014 update.

Department of Health, The Government of the Hong Kong

Special Administrative Region; December 2015.