Hong Kong Med J 2016 Oct;22(5):464–71 | Epub 26 Aug 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154714

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Violence against emergency department employees and the attitude of employees

towards violence

Halil Í Çıkrıklar, MD1;

Yusuf Yürümez, MD1;

Buket Güngör, MD2;

Rüstem Aşkın, MD2;

Murat Yücel, MD1;

Canan Baydemir, MD3

1 Department of Emergency Medicine, Sakarya University, Medical

Faculty, Sakarya, Turkey

2 Psychiatry Clinic, Ministry of Health, Şevket Yilmaz Training and Research Hospital, Bursa, Turkey

3 Department of Biostatistics, Eskişehir Osmangazi University, Medical Faculty, Eskişehir, Turkey

Corresponding author: Dr Halil Í Çıkrıklar (halilcikriklar@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: This study was conducted to evaluate

the occurrence of violent incidents in the workplace

among the various professional groups working

in the emergency department. We characterised

the types of violence encountered by different

occupation groups and the attitude of individuals

working in different capacities.

Methods: This cross-sectional study included 323

people representing various professional groups

working in two distinct emergency departments in

Turkey. The participants were asked to complete

questionnaires prepared in advance by the

researchers. The data were analysed using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows

version 15.0).

Results: A total of 323 subjects including 189 (58.5%) men and 134 (41.5%) women participated in the study. Their mean (± standard deviation) age was 31.5 ± 6.5 years and 32.0 ± 6.9 years, respectively. In all, 74.0% of participants had been subjected to verbal or physical violence at any point since starting employment in a medical profession. Moreover, 50.2% of participants stated

that they had been subjected to violence for more

than 5 times. Among those who reported being

subjected to violence, 42.7% had formally reported

the incident(s). Besides, 74.3% of participants did not enjoy their profession, did not want to

work in the emergency department, or would

prefer employment in a non–health care field after

being subjected to violence. According to

the study participants, the most common cause of

violence was the attitude of patients or their family

members (28.7%). In addition, 79.6% (n=257) of

participants stated that they did not have adequate

safety protection in their working area. According

to the study participants, there is a need for legal

regulations to effectively deter violence and increased

safety measures designed to reduce the incidence of

violence in the emergency department.

Conclusion: Violence against employees in the

emergency department is a widespread problem. This

situation has a strong negative effect on employee

satisfaction and work performance. In order to

reduce the incidence of violence in the emergency

department, both patients and their families should

be better informed so they have realistic expectations

as an emergency patient, deterrent legal regulations

should be put in place, and increased efforts should

be made to provide enhanced security for emergency

department personnel. These measures will reduce

workplace violence and the stress experienced by

emergency workers. We expect this to have a positive

impact on emergency health care service delivery.

New knowledge added by this study

- The prevalence of violence against employees in emergency departments is high.

- Various measures can be implemented to reduce the incidence of violence in the emergency department.

Introduction

Violence, which has been ever present throughout

the history of humanity, is defined as a threat or

application of possessed power or strength towards

another person, self, a group, or a community in

order to cause injury and/or loss.1 The World Health

Organization defines violence as “physical assault,

homicide, verbal assault, emotional, sexual or racial

harassment”.2

Workplace violence is defined as “abuse or

attacks by one or more people on an employee

within the workplace”.3 The health care field, which

encompasses a wide range of employees, is among

those in which workplace violence is common.4

Violence in the health care field is defined as “risk

to a health worker due to threatening behaviour,

verbal threats, physical assault and sexual assault

committed by patients, patient relatives, or any other

person”.3

According to the 2002 Workplace Violence

in the Health Sector report, 25% of all violent

incidents occurred in the health care sector.5 A study

conducted in the United States determined that the

risk of being subjected to violence is 16 times higher

in the health care sector relative to other service

sectors.6 Within the health care field, the department

that is most frequently exposed to violence is the

emergency department (ED).3 7 8 9 In this context,

verbal and physical attacks by dissatisfied patients

and their relatives are at the forefront.10 11

In this study we aimed to determine the extent

of violence towards ED employees, analyse the

attitude of the staff exposed to violence, and propose

possible solutions.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the EDs

of Şevket Yilmaz Training and Research Hospital and

Sakarya University between 1 July and 15 August 2012. Employees of

ED—including doctors, nurses, health care officials,

Emergency Medical Technicians (EMT), secretaries,

laboratory technicians, radiology technicians, and

security and cleaning staff—were included in the

study. The questionnaire was prepared in accordance

with previous publications3 10 11 and distributed to

participants. All study participants were provided

with information regarding the objectives of the

study and were given instructions for completing the

form. Of the 437 ED employees working in the two

hospitals, 323 (73.9%) agreed to participate in the

study and returned a completed questionnaire.

In addition to demographic information,

the questionnaire contained questions about the

number of violent incidents to which the individual

had been subjected to, the type of violence, and

whether the subject reported the incident or the

reason for not reporting. Additional questions

concerned a description of the person(s) responsible

for the violence, the estimated age of the person(s)

responsible for the violence, and the severity of

the violence. We also asked participants about

their attitude following the violent incident and

suggestions for reducing violence in the ED.

This study was conducted in accordance with

the principles of the 2008 Helsinki Declaration. The

data were analysed using the Statistical Package for

the Social Sciences (Windows version 15.0; SPSS

Inc, Chicago [IL], US). Both proportions and mean ±

standard deviation were used to represent the results.

The Student’s t test, Pearson’s Chi squared test, and

the Monte Carlo Chi squared tests were used to

evaluate observed differences between groups and

a P value of <0.05 was considered to represent a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Among the 323 participants included in the study,

189 (58.5%) were male and 134 (41.5%) were female.

The mean age of the male participants was 31.5

± 6.5 years (range, 18-55 years) and that of the

female participants was 32.0 ± 6.9 years (range,

20-52 years). There was no significant difference in

the age distribution between the male and female

participants (P=0.476).

When participants were asked if they had ever

been exposed to verbal or physical violence in the

workplace during the course of their career, 239

(74.0%) indicated that they had been

subjected to one or the other, and 57 (17.6%) reported

being subjected to both verbal and physical violence.

Among the participants who were subjected to

violence, 162 (67.8%) reported being the

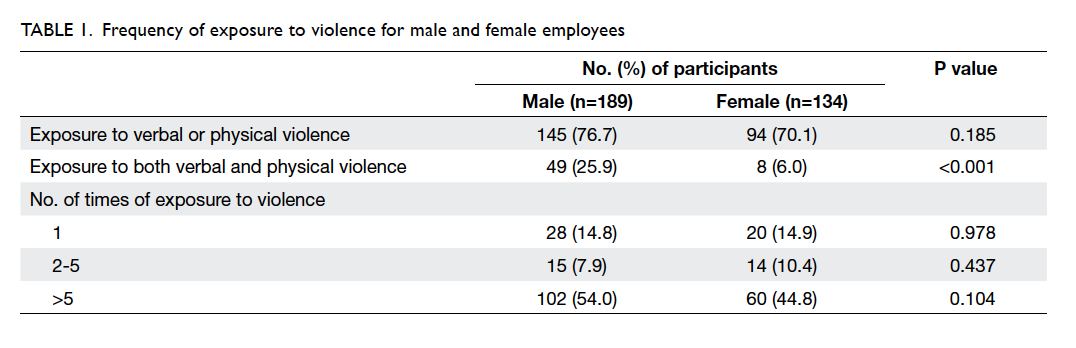

victim of more than five violent incidents (Table 1).

The frequency of exposure to violence and

the frequency of exposure to more than five violent

incidents were similar for both men and women

(P=0.185 and 0.104, respectively). Nonetheless,

25.9% of men reported both verbal and physical

violence compared with only 6.0% of women,

suggesting that the incidence of verbal and physical

violence against men was greater than that against

women (P<0.001) [Table 1].

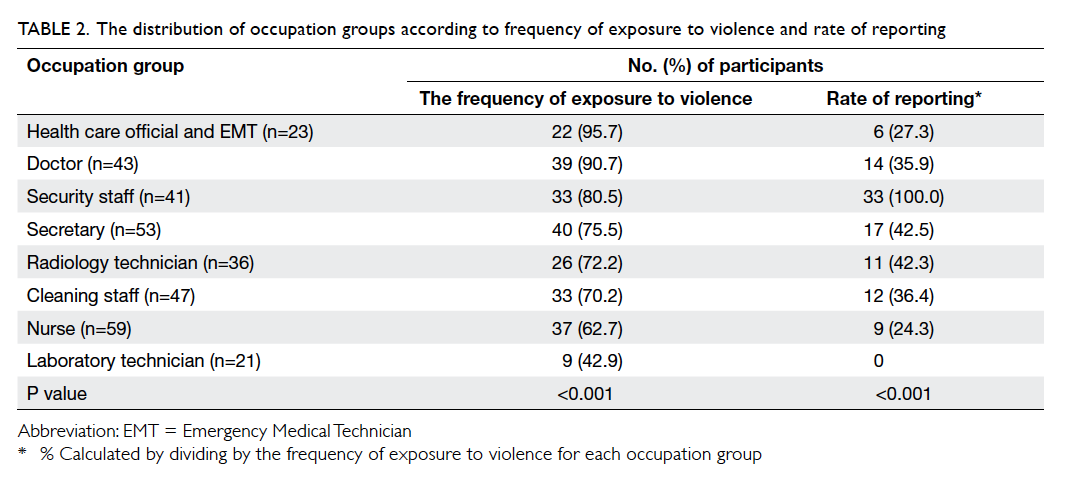

We investigated the frequency of exposure

to violence and the reported incidence of violence

among various occupation groups (Table 2). The prevalence of exposure to violence was the highest

among health care officials, EMTs, doctors, and

security staff (P<0.001). In addition, only 102 (42.7%)

out of 239 participants reported these violent

incidents. It is notable that although the rate of

incident reporting was 100% among security staff,

none of the laboratory technicians reported the

violent incidents (P<0.001).

Table 2. The distribution of occupation groups according to frequency of exposure to violence and rate of reporting

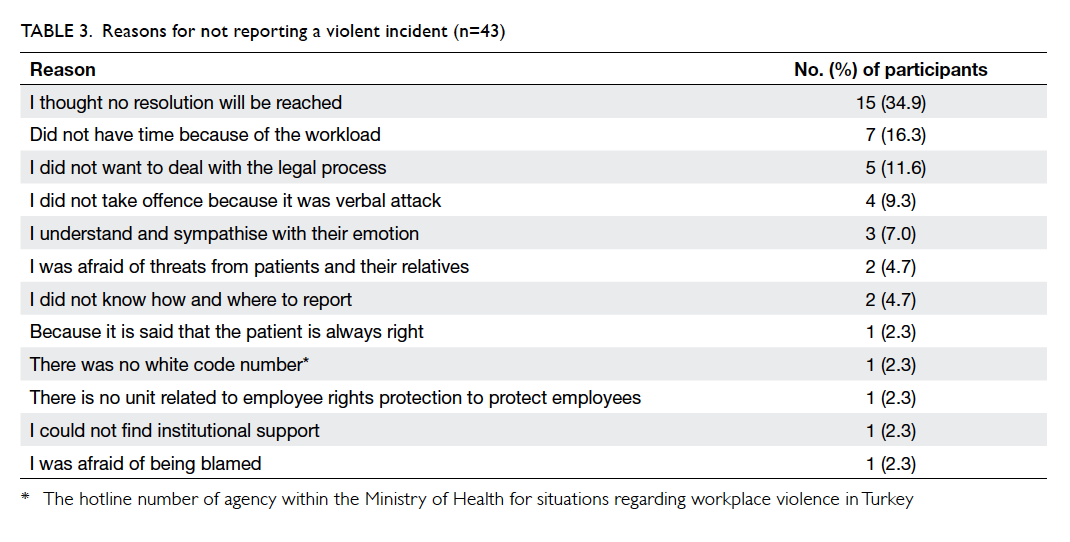

A total of 43 (31.4%) out of the 137 study

participants who had been exposed to violence but

had not reported the incident provided reasons

(Table 3). The most common reason for not notifying the authorities was the perception that “no

resolution will be reached”. Other important reasons

included the heavy workload, not wanting to deal

with the legal process, disregarding verbal attacks,

understanding/sympathising with the emotions of

patients and their relatives, fear of the threat from

patients and their relatives, and not knowing how

and where to report such incidents.

A total of 248 participants responded to a

question regarding the identity of the person who

was to blame for the violence in ED in general (not

their own experiences). Accordingly, 65.3% (n=162)

stated that the patient’s relatives were responsible,

27.0% (n=67) stated that both the patients and

their relatives were responsible, and 5.2% (n=13)

placed sole responsibility on the patients. Six (2.4%)

participants stated that they had been subjected to

violence from other health care professionals.

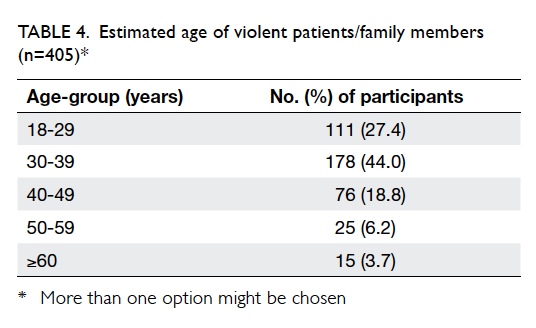

When we asked individuals to estimate the

age of the person(s) causing the violence that they

had experienced, respondents who were exposed to

multiple violent incidents answered this question by

selecting multiple options and a total of 405 answers

were obtained. As shown in Table 4, the majority (71.4%) of people responsible for violent incidents

were young patients and patient relatives between

the ages of 18 and 39 years.

When participants who were exposed

to violence were asked who caused the violent

incident, three (1.3%) participants stated that they

themselves were responsible, five (2.1%) indicated that both sides were responsible, and the

remaining 231 (96.7%) held the attacker

responsible.

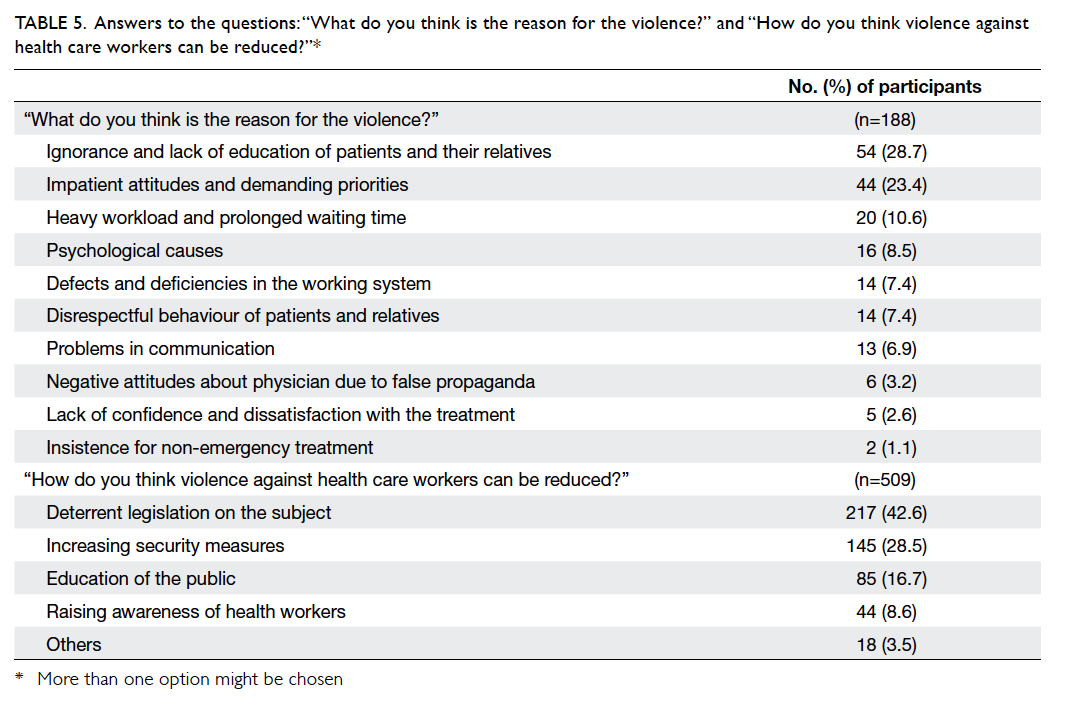

Participants were asked “What do you

think is the reason for the violence?”. A total of 181

(56.0%) participants responded to this question.

Some participants indicated more than one reason

and a total of 188 answers were obtained. The top 10

most common responses to this question are given in

descending order of frequency in Table 5. The most common cause of violence was ignorance and lack

of education of patients and their relatives (28.7%), followed by the impatient attitudes and demanding

priorities (23.4%) and the heavy workload and prolonged waiting time (10.6%).

Table 5. Answers to the questions: “What do you think is the reason for the violence?” and “How do you think violence against health care workers can be reduced?”

Participants were asked “How do you

think violence against health care workers can be

reduced?”. Some participants indicated more than

one reason and a total of 509 answers were obtained.

They considered the most important steps suggested

to reduce violence against ED employees were the

enactment of deterrent legislation (42.6%), increased

security measures in hospitals (28.5%), and improved

public education (16.7%) [Table 5].

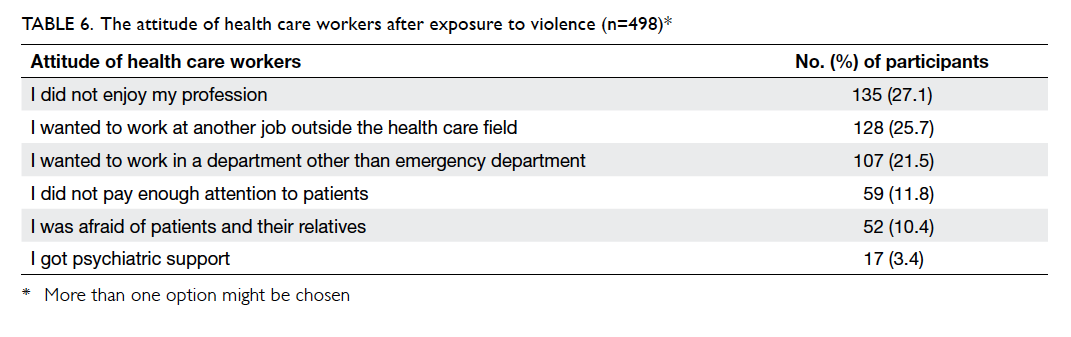

Participants were asked about their attitude

after experiencing violence. Some respondents gave

more than one answer and a total of 498 answers

were obtained. There were 27.1% of participants who

did not enjoy working in their current profession,

25.7% wanted to work in non–health care field, and

21.5% did not want to work in the ED (Table 6).

A total of 96.3% (n=311) of participants

answered “Yes” to the question “Do you think

that the violence against health care workers has

increased in recent years?” Moreover, 90.7% (n=293)

of the participants answered “Yes” to the question

“Do news reports regarding violence against health

care workers affect you?”. Then, when participants

were asked “How does the news affect you?”, 64.7%

(n=209) reported that they were “sad”, 44.3% (n=143)

said they were “angry”, and 18.9% (n=61) said they

were “scared”.

When participants were asked “Are there

sufficient security measures in your workplace?”,

only 66 (20.4%) participants gave a positive response,

while 257 (79.6%) responded negatively. Among the

41 participants working as security staff, 33 (80.5%)

found the safety measures inadequate. Thus, both the

security staff and the general employee population

agreed that hospital security was inadequate.

Discussion

Workplace violence is the most prevalent in the

health care sector.4 The ED is the health care

unit with the highest frequency of exposure to

violence.3 7 8 9 According to several previous studies,

the proportion of health care professionals who

report prior exposure to violence in the workplace

ranges from 45% to 67.6%.3 8 12 13 14 The rate of violence against ED employees (79%-99%), however, is higher

than the average for the health care field.15 16 17

Emergency services are high-risk areas

for patients and staff with regard to workplace

violence18 19 20 21; 24-hour accessibility, a high-stress

environment, and the apparent lack of trained

security personnel are underlying factors.22

Workplace violence negatively affects the morale of

health care workers and negatively affects the health

and effectiveness of presentation.23 24 25 26

Our study was conducted among ED employees

of two different hospitals. We investigated the rate of

exposure to verbal or physical violence. Among the

participants, 239 (74.0%) stated that they had been

subjected to exposure to violence, and 57 (17.6%)

reported having been exposed to both verbal and

physical violence. A study in Turkey found that

among ED employees, including nurses, in the İzmir

province of Turkey, 98.5% of respondents had been

subjected to verbal violence and 19.7% were exposed

to physical violence.16 In another study conducted

in Turkey, 88.6% of ED employees were subjected to

verbal violence and 49.4% reported having been the

victim of physical violence.17

In the present study, the rate of exposure to

violence by profession was 95.7% among health care

officials/EMTs, 90.7% among doctors, and 80.5%

among security personnel. According to Ayrancı et

al,3 exposure to violence was most common among

practitioners (67.6%) and nurses (58.4%). In another

study, Alçelik et al27 reported that nurses were

exposed to violence 3 times more often than other

health care professionals. In the present study, the

frequency of exposure to violence among nurses was

62.7%, which is lower than that in other professional

groups.

In the present study, the estimated age

distribution of patients and patient relatives

responsible for violent incidents showed that the

majority (71.4%) were between 18 and 39 years of

age. Other studies have reported that individuals

prone to violence are generally younger than 30

years.28

Health care workers are often subjected to verbal

and physical attacks from patients and their relatives

who are dissatisfied with the services provided.10 11 In the present study, the most common cause of

violence was the lack of education and ignorance of

the patients and their relatives. Heavy workload was

identified as another cause of workplace violence.

Factors such as patient stress and anxiety regarding

their condition, high expectations of the patients

and their relatives, lack of effective institutional and

legal arrangements aimed at preventing violence,

and the failure to effectively document the extent of

workplace violence contribute to the high frequency

of violence.12 There are several factors that increase

the risk of violence in health care institutions,

including 24-hour service, long waiting time for

patients, poor access to health care services, heavy

workload, limited staff, inadequate employee

training, and lack of security personnel.29 30

Previous studies conducted in Turkey revealed

that 60% of ED employees who were exposed to

violence did not report the incident. Among the

reasons for not reporting was a lack of confidence

in health care and executive leadership as well

as the justice system.12 In the present study, the

incident reporting rate was also low (42.7%) and the

most important reason (34.9%) for not reporting

was the perception that “no resolution will be

reached”. Indeed, a study found that there were no

repercussions for the attacker in 77% of instances.12

This suggests the perception that “no resolution will

be reached” is a valid one.

A heavy workload consumes the energy of

employees and reduces their ability to empathise

with patients and tolerate violent situations.

Sometimes verbal or physical conflicts may arise

between a stressed patient who may be subject to

long waiting times and exhausted and stressed health

care workers. Training regarding communication

with patients helps health care professionals to avoid

these problems.31 Effective communication alone,

however, is not sufficient and additional steps must

be taken to reduce waiting time of patients. Previous

studies have indicated that the most important

reason for patient dissatisfaction in the ED is the

waiting time.32 33 Yet, the most important reason for long waiting times is the heavy workload caused, in

part, by the discourteous attitude of patients and

their relatives. Studies have also shown that more

than half of patients who present to the ED are not

‘emergency patients’.34 35 36 Further education regarding

the definition of “emergency” and the practice of

effective triage may reduce the heavy workload in

the ED and associated violent incidents.

One previous study reported that verbal and

physical attacks by patients and their relatives are

the most important factors contributing to stress

among ED employees.37 Consistent exposure to

high-stress conditions resulting from exposure to

verbal and physical violence results in both physical

and mental exhaustion. As a result, a situation known

commonly as ‘burnout syndrome’ emerges.38 39 The

burnout syndrome is defined as holding a negative

view of current events, frequent despair, and lost

productivity and motivation.40 Reluctance among

physicians to work in the ED is one consequence of

burnout syndrome.41 In the present study, among the

participants who were subjected to violence, 21.5%

indicated that they wanted to work in a department

other than the ED, while 25.7% stated a desire to work

outside the health care field. In a study conducted in

Canada, 18% of participants who had been exposed

to violence stated that they did not want to work in

the ED, and 38% wanted to work outside the health

care field.9 Others indicated that they had quitted their

jobs because of workplace stress.9 In the present

study, 10.4% of ED employees stated that they were

afraid of patients and their relatives. In the same

Canadian study, 73% of respondents stated that after

experiencing violence they were afraid of patients.9

In our study, 96.3% of respondents thought that

there had been an increase in violence against ED

health care workers in recent years. Moreover, 79.6%

of respondents stated that the safety measures in

their institutions were insufficient. The participants

in the present study suggested that the preparation

of deterrent legislation, increased security measures,

and efforts to better educate the general population

regarding the appropriate use of ED resources will

help to reduce violence against health care workers.

Limitations

The study was carried out in only two hospitals in

Turkey that may not be representative of all hospitals.

In addition, participants could decide whether or

not to answer all questions and some questionnaires

were incomplete. The response rate was only 74%

and this might give rise to self-selection bias, that

is, those who did not respond may have had a higher

(or lower) exposure to violence than those who

responded. Hence, the various percentages reported

in this paper might be over- or under-estimated.

Conclusion

The results of the current study as well as those

of earlier studies indicate that the prevalence of

violence against ED employees is high. Factors

such as patient and stress of health care provider,

prolonged waiting times due to overcrowding in the

ED, negative attitude of discourteous patients and

their relatives, insufficient security measures, and

the lack of sufficiently dissuasive legal regulations

may contribute to increased violence in the ED.

These factors in turn increase stress among ED

employees, reduce job satisfaction, and lower the

quality of services provided. Measures to decrease

the workload in the ED and shorten waiting time

of patients, the adoption of legal policies that deter

violent behaviour, and increased security measures

in health care facilities should be reassessed. Steps

should be taken to educate the public in order to

reduce violence against health care workers.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Kocacik F. On violence [in Turkish]. Cumhuriyet Univ J

Econ Adm Sci 2001;2:1-2.

2. Violence and injury prevention. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/workplace/documents/en/index.html. Accessed

Nov 2012.

3. Ayrancı Ü, Yenilmez Ç, Günay Y, Kaptanoğlu C. The

frequency of being exposed to violence in the various

health institutions and health profession groups. Anatol J

Psychiatry 2002;3:147-54.

4. Wells J, Bowers L. How prevalent is violence towards

nurses working in general hospitals in the UK? J Adv Nurs

2002;39:230-40. Crossref

5. Workplace violence in the health sector. Framework

guidelines for addressing workplace violence in the health

sector. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---sector/documents/publication/wcms_160912.pdf. Accessed Nov 2012.

6. Kingma M. Workplace violence in the health sector: a

problem of epidemic proportion. Int Nurs Rev 2001;48:129-30. Crossref

7. Gülalp B, Karcıoğlu, Köseoğlu Z, Sari A. Dangers faced

by emergency staff: experience in urban centers in southern

Turkey. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2009;15:239-42.

8. Lau J, Magarey J, McCutcheon H. Violence in the

emergency department: a literature review. Aust Emerg

Nurs J 2004;7:27-37. Crossref

9. Fernandes CM, Bouthillette F, Raboud JM, et al. Violence

in the emergency department: a survey of health care

workers. CMAJ 1999;161:1245-8.

10. Yanci H, Boz B, Demirkiran Ö, Kiliççioğlu B, Yağmur F.

Medical personal subjected to the violence in emergency

department—enquiry study. Turk J Emerg Med 2003;3:16-20.

11. Sucu G, Cebeci F, Karazeybek E. Violence by patient and

relatives against emergency service personnel. Turk J

Emerg Med 2007;7:156-62.

12. Çamci O, Kutlu Y. Determination of workplace violence

toward health workers in Kocaeli. J Psychiatr Nurs

2011;2:9-16.

13. Stirling G, Higgins JE, Cooke MW. Violence in A&E

departments: a systematic review of the literature. Accid

Emerg Nurs 2001;9:77-85. Crossref

14. Sönmez M, Karaoğlu L, Egri M, Genç MF, Günes G, Pehlivan E. Prevalence of workplace violence against health

staff in Malatya. Bitlis Eren Univ J Sci Technol 2013;3:26-31.

15. Stene J, Larson E, Levy M, Dohlman M. Workplace violence

in the emergency department: giving staff the tools and

support to report. Perm J 2015;19:e113-7. Crossref

16. Senuzun Ergün F, Karadakovan A. Violence towards

nursing staff in emergency departments in one Turkish

city. Int Nurs Rev 2005;52:154-60. Crossref

17. Boz B, Acar K, Ergin A, et al. Violence toward health care

workers in emergency departments in Denizli, Turkey. Adv

Ther 2006;23:364-9. Crossref

18. Joa TS, Morken T. Violence towards personnel in out-of-hours

primary care: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Prim

Health Care 2012;30:55-60. Crossref

19. Magnavita N, Heponiemi T. Violence towards health care

workers in a Public Health Care Facility in Italy: a repeated

cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:108. Crossref

20. Arimatsu M, Wada K, Yoshikawa T, et al. An epidemiological

study of work-related violence experienced by physicians

who graduated from a medical school in Japan. J Occup

Health 2008;50:357-61. Crossref

21. Taylor JL, Rew L. A systematic review of the literature:

workplace violence in the emergency department. J Clin

Nurs 2011;20:1072-85. Crossref

22. Gacki-Smith J, Juarez AM, Boyett L, Homeyer C, Robinson

L, MacLean SL. Violence against nurses working in US

emergency departments. J Nurs Adm 2009;39:340-9. Crossref

23. Kowalenko T, Gates D, Gillespie GL, Succop P, Mentzel

TK. Prospective study of violence against ED workers. Am

J Emerg Med 2013;31:197-205. Crossref

24. Position statement: violence in the emergency care setting.

Available from: https://www.ena.org/government/State/Documents/ENAWorkplaceViolencePS.pdf. Accessed Nov

2012.

25. Workplace violence. Washington, DC: United States

Department of Labor; 2013. Available from: http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/workplaceviolence/index.html. Accessed Nov

2012.

26. Adib SM, Al-Shatti AK, Kamal S, El-Gerges N, Al-Raqem

M. Violence against nurses in healthcare facilities in

Kuwait. Int J Nurs Stud 2002;39:469-78. Crossref

27. Alçelik A, Deniz F, Yeşildal N, Mayda AS, Ayakta Şerifi B.

Health survey and life habits of nurses who work at the

medical faculty hospital at AIBU [in Turkish]. TAF Prev

Med Bull 2005;4:55-65.

28. Young GP. The agitated patient in the emergency

department. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1987;5:765-81.

29. Stathopoulou HG. Violence and aggression towards health

care professionals. Health Sci J 2007;2:1-7.

30. Hoag-Apel CM. Violence in the emergency department.

Nurs Manage 1998;29:60,63.

31. Yardan T, Eden AO, Baydın A, Genç S, Gönüllü H.

Communication with relatives of the patients in emergency

department. Eurasian J Emerg Med 2008;7:9-13.

32. Al B, Yıldırım C, Togun İ, et al. Factors that affect patient satisfaction in emergency department. Eurasian J Emerg

Med 2009;8:39-44.

33. Yiğit Ö, Oktay C, Bacakoğlu G. Analysis of the patient

satisfaction forms about Emergency Department services

at Akdeniz University Hospital. Turk J Emerg Med

2010;10:181-6.

34. Kiliçaslan İ, Bozan H, Oktay C, Göksu E. Demographic properties of patients presenting to the emergency

department in Turkey. Turk J Emerg Med 2005;5:5-13.

35. Ersel M, Karcıoğlu Ö, Yanturali S, Yörüktümen A, Sever M, Tunç MA. Emergency Department utilization

characteristics and evaluation for patient visit

appropriateness from the patients’ and physicians’ point of

view. Turk J Emerg Med 2006;6:25-35.

36. Aydin T, Aydın ŞA, Köksal Ö, Özdemir F, Kulaç S, Bulut M. Evaluation of features of patients attending the Emergency

Department of Uludağ University Medicine Faculty

Hospital and emergency department practices. Eurasian J

Emerg Med 2010;9:163-8. Crossref

37. Kalemoglu M, Keskin O. Evaluation of stress factors and

burnout in the emergency department staff [in Turkish].

Ulus Travma Derg 2002;8:215-9.

38. Ferns T, Stacey C, Cork A. Violence and aggression in the

emergency department: Factors impinging on nursing

research. Accid Emerg Nurs 2006;14:49-55. Crossref

39. Keser Özcan N, Bilgin H. Violence towards healthcare

workers in Turkey: A systematic review [in Turkish].

Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci 2011;31:1442-56. Crossref

40. Maslach C. Burned-out. Hum Behav 1976;5:16-22.

41. Dwyer BJ. Surviving the 10-year ache: emergency practice

burnout. Emerg Med Rep 1991;23:S1-8.