Hong Kong Med J 2016 Oct;22(5):445–53 | Epub 19 Aug 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154747

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Clinical transition for adolescents with developmental disabilities in Hong Kong: a pilot study

Tamis W Pin, PhD;

Wayne LS Chan, PhD;

CL Chan, BSc (Hons) Physiotherapy;

KH Foo, BSc (Hons) Physiotherapy;

Kevin HW Fung, BSc (Hons) Physiotherapy;

LK Li, BSc (Hons) Physiotherapy;

Tina CL Tsang, BSc (Hons) Physiotherapy

Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hunghom, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Tamis W Pin (tamis.pin@polyu.edu.hk)

This paper was presented as a poster at the Hong Kong Physiotherapy Association Conference 2015, Hong Kong on 3-4 November 2015.

Abstract

Introduction: Children with developmental

disabilities usually move from the paediatric to adult

health service after the age of 18 years. This clinical

transition is fragmented in Hong Kong. There are

no local data for adolescents with developmental

disabilities and their families about the issues they

face during the clinical transition. This pilot study

aimed to explore and collect information from

adolescents with developmental disabilities and their

caregivers about their transition from paediatric to

adult health care services in Hong Kong.

Methods: This exploratory survey was carried out

in two special schools in Hong Kong. Convenient

samples of adolescents with developmental

disabilities and their parents were taken. The

questionnaire was administered by interviewers in

Cantonese. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse

the answers to closed-ended questions. Responses to

open-ended questions were summarised.

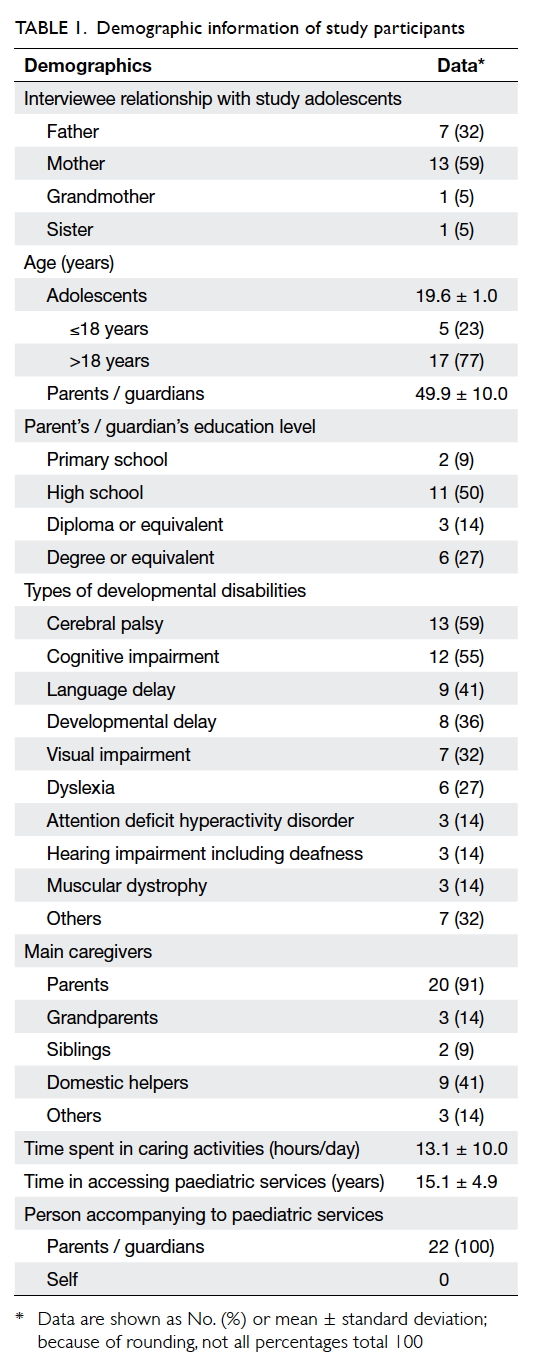

Results: In this study, 22 parents (mean age ±

standard deviation: 49.9 ± 10.0 years) and 13

adolescents (19.6 ± 1.0 years) completed the face-to-face questionnaire. The main diagnoses of the

adolescents were cerebral palsy (59%) and cognitive

impairment (55%). Of the study parents, 77% were

reluctant to transition. For the 10 families who did

move to adult care, 60% of the parents were not

satisfied with the services. The main reasons were

reluctant to change and dissatisfaction with the adult

medical service. The participants emphasised their

need for a structured clinical transition service to

support them during this challenging time.

Conclusions: This study is the first in Hong Kong

to present preliminary data on adolescents with

developmental disabilities and their families during

transition from paediatric to adult medical care.

Further studies are required to understand the needs

of this population group during clinical transition.

New knowledge added by this study

- These results are the first published findings on clinical transition for adolescents with developmental disabilities in Hong Kong.

- Dissatisfaction with the adult health services and reluctance to change were the main barriers to clinical transition.

- The concerns and needs of the families were similar regardless of whether adolescents had physical or cognitive disabilities.

- A structured clinical transition service is required for adolescents with developmental disabilities and their parents.

- Further in-depth studies are required to examine the needs for and concerns about clinical transition for all those involved. This should include adolescents with developmental disabilities, their parents or caregivers, and service providers in both paediatric and adult health services.

Introduction

Advances in medical management now enable

children with developmental disabilities (DD)

who may previously have died to live well into

adulthood.1 Such disabilities are defined as any

condition that is present before the age of 22 years

and due to physical or cognitive impairment or a

combination of both that significantly affects self-care,

receptive and expressive language, mobility,

learning, independent living, or the economic

independence of the individual.2 The transition

from adolescence to adulthood is a critical period

for all young people.3 In a clinical context, adult

transition is “the purposeful, planned movement of

adolescents and young adults with chronic physical

and medical conditions from child-centered to adult-oriented

health-care systems”.4 In 2001, a consensus

statement with guidelines was endorsed to ensure

adolescents with DD, who depend on coordinated

health care services, make a smooth transition to

the adult health care system in order to receive the

services that they need in developed countries such

as the United States.5

Researchers have identified needs and factors

necessary for the successful transition of adolescents

with DD.6 7 From the adolescent’s perspective,

barriers to success include their dependence on

others, reduced treatment time and access to

specialists in the adult health service, lack of information

about transition, and lack of involvement in the

decision-making process. Parents of adolescents

with DD were reluctant or confused about changing

responsibilities during the transition period. The

majority of challenges came from the service

systems and included unclear eligibility criteria

and procedures, limited time and lack of carer

training, fragmented adult health service provision, lack

of communication between service providers, and

inaccessibility to resources including information.6 7

Based on the 2015 census of ‘Persons with

disabilities and chronic diseases in Hong Kong’ from

the Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department,

there were 22 100 (3.8%) people with disability

(excluding cognitive impairment) aged between

15 and 29 years, ie who were transitioning from

the paediatric to adult health service.8 According

to the Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, all public

hospitals, and specialist and general out-patient

clinics are organised into seven hospital clusters

based on geographical location.9 The Duchess of

Kent Children’s Hospital (DKCH) is a tertiary centre

that provides specialised services for children with

orthopaedic problems, spinal deformities, cerebral

palsy and neurodevelopmental disorders, and

neurological and degenerative diseases. Unlike

overseas health care, there is no children’s hospital in

Hong Kong that provides an acute health service. All

paediatric patients go to the same hospital as adult

patients but are triaged into the paediatric section

for management by both in-patient and out-patient

services. The specialised out-patient clinic list under

each hospital cluster varies. Children with DD might

receive services from general paediatrics clinic,

a cerebral palsy clinic, Down’s clinic, behavioural

clinic, or paediatric neurology out-patient clinic.

Once a child reaches the age of 18 years, they are

referred to the adult section of the same hospital

for continued care. They will be followed up in

neurology or movement disorder clinics, where other

patients with adult-onset neurological conditions

or movement disorders, such as stroke, Parkinson’s

disease, multiple sclerosis are followed up. There

is no separate specialised clinic for complex child-onset

DD.10

Although adult transition for adolescents with

DD has been recognised as a crucial area in health

care overseas, it is an under-developed service in

Hong Kong.11 A local study found that there is a

service gap in adult transition for young people

with chronic medical conditions, such as asthma,

diabetes, and epilepsy. Training and education

are urgently required for both service providers

and young people with chronic health conditions

and their families.11 It is unclear if the challenges

and barriers identified in overseas literature6 7 are

applicable to Hong Kong, where the paediatric and

adult health services, especially the medical services,

are located in the same building. At present, no

study has been conducted with adolescents with DD

and their families in Hong Kong about the issues

they face during clinical transition. As a start, in this

pilot study, we aimed to explore the acceptance of

clinical transition and identify the main barriers to

successful clinical transition for adolescents with

DD and their caregivers in Hong Kong.

Methods

Participants

A survey study was conducted on a convenience

sample of adolescents and/or their caregivers, who

were recruited from two special high schools (Hong Kong Red Cross John F Kennedy Centre [JFK] and Haven of

Hope Sunnyside School [HOH]) in Hong Kong. Students from

JFK have primarily physical and multiple disabilities

including cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy and

those from HOH have severe cognitive impairment.

Both schools provide rehabilitation services on

site including physiotherapy, occupational therapy,

speech therapy, nursing support, and family support

via the school social workers. The medical out-patient

services for the students fall under different

hospital clusters, depending on where the students’

families live. The parents are responsible for taking

their adolescent children for medical review. As there

was no previous study on which basis to calculate

the required sample size and as a pilot study, we

aimed to recruit 10 adolescents and their parents/caregivers in each school.

The inclusion criteria of the adolescents were: (1) aged 16 to 19 years and (2) a diagnosis of DD.

All participating adolescents and/or their parents or

legal guardians gave written informed consent before

the survey. For adolescents with severe cognitive

impairment, consent was sought from their parents

as proxy and only their parents participated in the

survey. This pilot study was approved by the Human

Subjects Ethics Sub-committee of the Hong Kong

Polytechnic University.

Survey

A specific questionnaire was developed for this

pilot study to collect information relative to: (1)

demographic characteristics of the participants; (2)

whether or not the study participants were aware of

the transition and the information source(s); (3) if

the study participants were willing to transition to

the adult health service and the underlying reasons;

(4) for those who had transitioned, if they were

satisfied with the adult health service and the underlying

reasons; and (5) the opinion of the study participants

of the clinical transition service. As a pioneer pilot

study, health service included both medical and

rehabilitation services and the study aimed to explore

the general issues faced by this group of adolescents

and their families during clinical transition. Lastly,

as we predicted that the competency level of the

adolescents and their caregivers in managing their

disabilities might influence their perception of

clinical transition, information about their self-rated

competency level was also collected. Questions in

the latter part were based on information from the

Adolescent Transition Care Assessment Tool and

were designed to assist health care professionals

to provide a better transition for adolescents with

chronic illness.12 The whole survey was administered

by interviewers for the study adolescents and/or their

caregivers separately in Cantonese. All interviews

were recorded for data analyses.

The survey comprised closed- and open-ended

questions. The closed-ended questions were designed

to require a dichotomous answer, ie ‘yes’ or ‘no’, or

an answer from a set of choices. For example, when

asked about the sources of information about clinical

transition, the study participants could choose

their answers from a list of professionals such as

paediatricians, social workers, physiotherapists, and

school teachers. The open-ended questions focused

on the reasons for an earlier response. For example,

when asked if they wished to move to the adult health service, the individual would first answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’, then give their reasons. For the questions about

self-perceived competency level, study participants

read a number of statements (8 for the adolescents

and 14 for parents) and indicated how much they

agreed with the statement using a Likert-scale from

‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’.

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics—including mean, median,

standard deviation, or quartiles—were used

to analyse the responses to the closed-ended

questions. Discussion of the open-ended questions

was transcribed and summarised by five team

members (CLC, KHF, KHWF, LKL, and TCLT). The

content was analysed and themes were identified

independently by two other team members (TWP

and WLSC). These themes were discussed and a

consensus reached by all team members.

Results

Thirteen potential families were approached at the

JFK via the physiotherapist of the school anticipating

possible refusal by some. All the students and their

parents agreed to participate, so all were included.

Ten families were approached at the HOH via the

social worker at the school but one parent declined

the offer and no other family was interested in

participating in the study. Since the students from

HOH, who were cognitively impaired, were not able

to be interviewed, only their parents/caregivers

were interviewed. As a result, 22 parents (13 from

the JFK and 9 from the HOH) and 13 adolescents

(all from the JFK) were asked to complete the

face-to-face survey. The demographic data of the

participants are listed in Table 1. Cerebral palsy and

cognitive impairment were the principal types of

DD. All adolescents received rehabilitation from the

Hospital Authority and/or from their special school.

All the adolescents accessed between four and seven

paediatric medical specialists (eg paediatrician,

neurologist, orthopaedic surgeon) and rehabilitation

services (eg physiotherapy, occupational therapy,

speech therapy) indicating their complex needs.

Over 90% of the JFK students were followed up at the

DKCH that is within walking distance of the school

(personal communication, Senior Physiotherapist at

JFK).

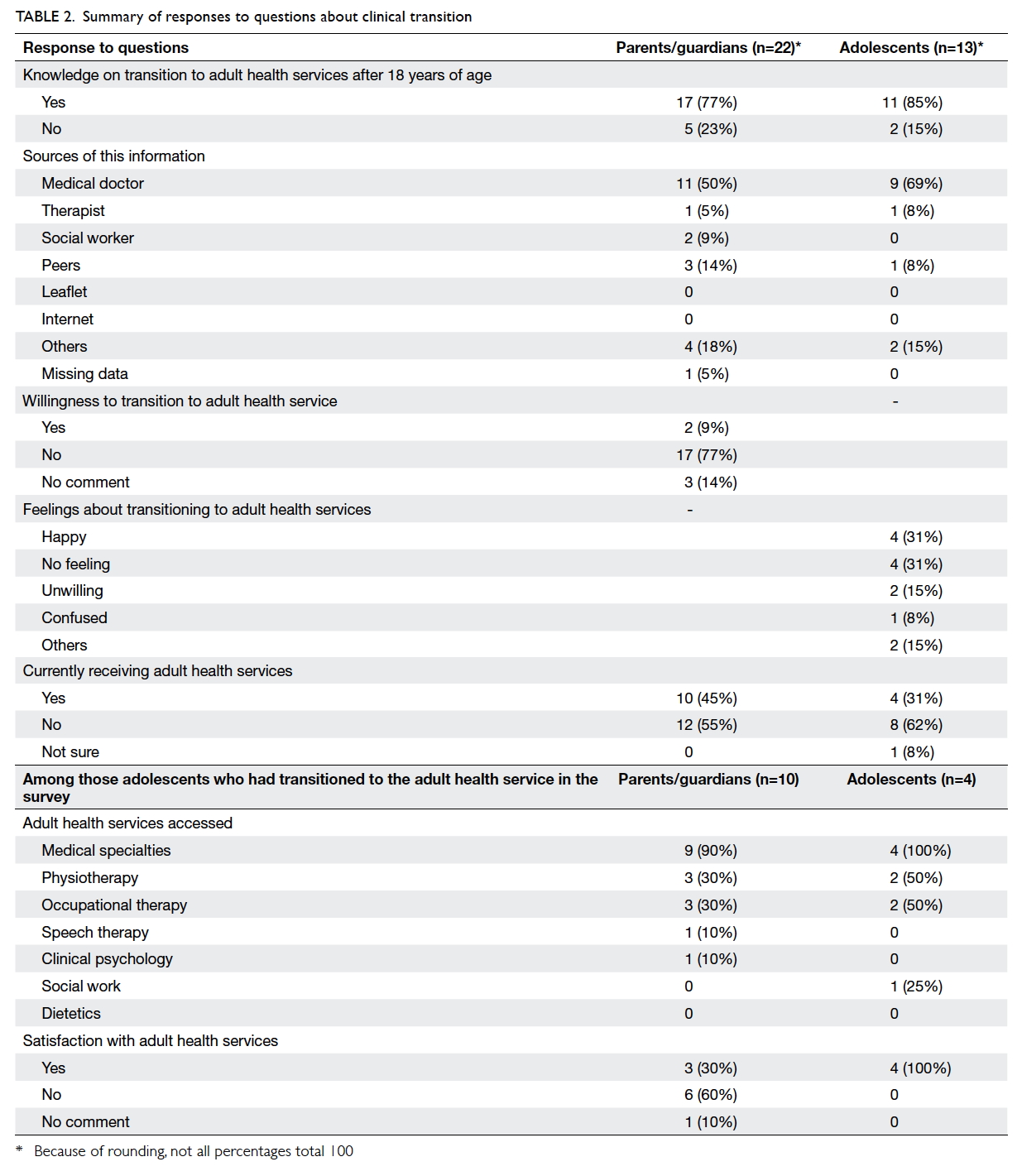

Table 2 summarises the participant responses

about clinical transition. The majority of the parents

(77%) and adolescents (85%) knew that clinical

transition to adult care would occur at 18 years of age.

They were mainly informed by their paediatrician

(50% of parents and 69% of adolescents). Most

parents (77%) were reluctant to make this move.

Ten parents stated that their adolescent child was

already receiving care from the adult sector and over

half of them (60%) were dissatisfied with the service.

Four of the 13 adolescents clearly stated that they

had transitioned to the adult health service during

the survey and all of them were happy with the

transition. Among those 17 families who knew that clinical transition to adult care would occur at 18 years of age, 10 adolescents were all over 18 years old, whereas those in another seven (41%) families were also over 18 years old and still receiving services from the paediatric sector at the time of the study.

When asked why they were not willing to the

transition or why they were dissatisfied after the

transition, the parent responses could be summed up

as two main areas of concern: reluctance to change

and dissatisfaction with the adult health services. Most

parents (16/22, 73%) did not want to change their

existing care circumstances. When asked why, some

parents cited dissatisfaction with the adult health service or

health system (for the latter, 13/22, 59% of parents).

For example, parents found it difficult to attend the

follow-up appointments using public transport.

Although there was a free shuttle bus service for

families who needed it, parents were frustrated by

the limited service.

Some parents also wanted more flexible

visiting hours in the adult hospital so that they could

look after their adolescent children, especially those

who were cognitively impaired. The parents worried

about the quality of care for their children who

were entirely dependent for their daily activities.

They were also unhappy about the waiting time for

medical appointments and stated that their children

with DD had a short attention span and were unable

to control their behaviour. Long waiting times in a

crowded waiting area, which is commonly observed

in the adult setting, could easily trigger their

behavioural problems.

There was also dissatisfaction with the adult

health service providers (13/22, 59% of parents). Parents

often found that the adult medical staff demonstrated

limited understanding and knowledge of their child’s

clinical presentation and abilities, especially for those

with severe cognitive impairment. The adult health

service providers did not know how to communicate

with the cognitively impaired adolescents and

treated them as other normal adults.

There is no formal clinical transition service in

Hong Kong but when asked, the majority of parents

(21/22, 95%) and adolescents (11/13, 85%) stated

that they would welcome such a service. About two

thirds of the study parents and adolescents (23/35,

66%) would like the clinical transition service to

support them during the clinical transition. About

one third of the parents (7/22, 32%) believed that the

service could act as a bridge linking the paediatric

and adult health services, providing information about

available services in the adult sector.

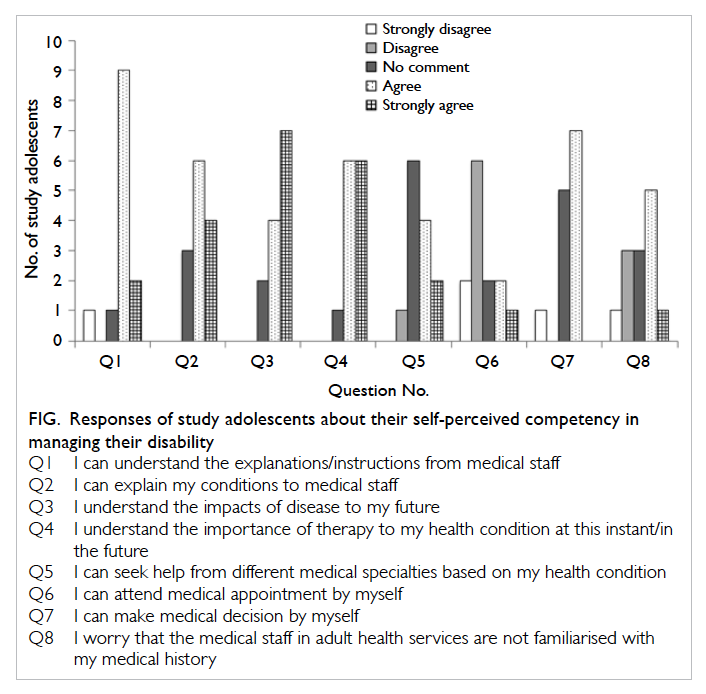

The Figure summarises the responses of

adolescents for self-perceived competency in

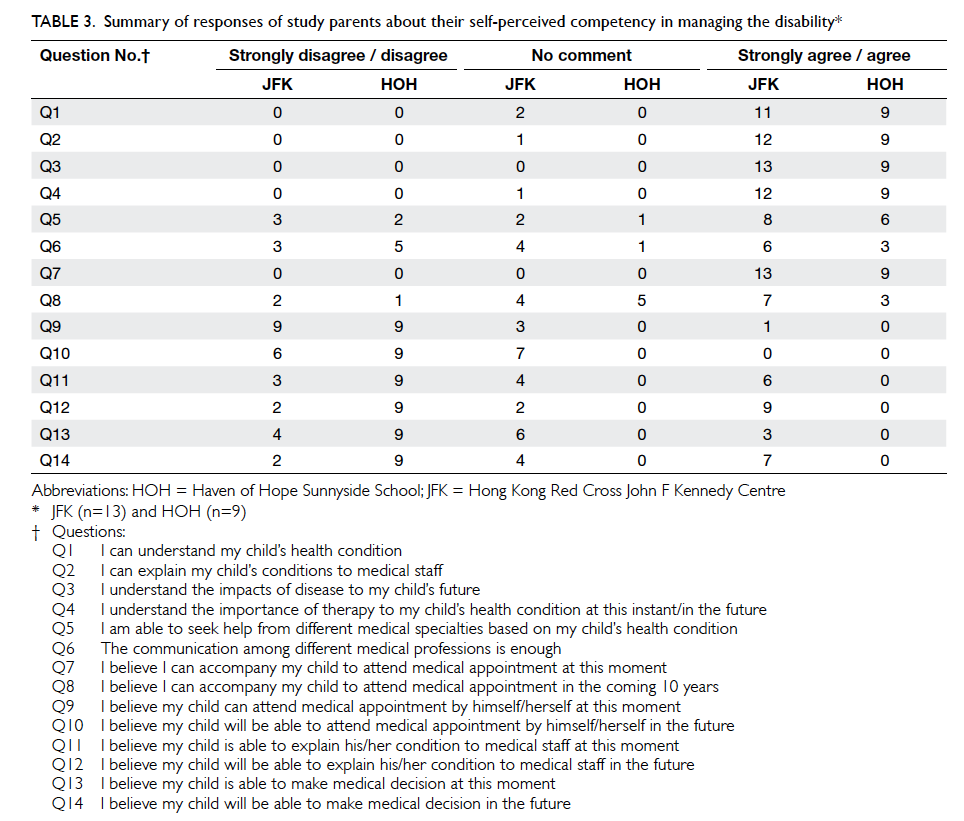

managing their disability, and Table 3 summarises

the study parents’ responses. Most adolescents

demonstrated understanding of instructions (11/13,

85%), confidence in communicating with the service

providers about their condition (10/13, 77%), and

understanding the importance of treatments for

their condition (12/13, 92%) [Fig]. About half were

confident in seeking help from different specialties

according to their condition (6/13, 46%) and making

medical decisions (7/13, 54%) [Fig]. Over half of the adolescents, however, lacked the confidence to

attend routine medical visits on their own (8/13,

62%) and worried about the unfamiliar adult medical

service (6/13, 46%) [Fig]. Most parents stated that

they were familiar with their children’s medical

conditions and treatments (20/22, 91%) and able to

seek help from different medical specialties based on

their child’s condition (14/22, 64%) [Table 3]. Only

a minority of parents (1/22, 5%), however, believed

that their children were capable of attending medical

appointments on their own. Less than half of the

parents believed that their children would be able to

explain their medical condition (9/22, 41%) or make

independent clinical decisions in the future (7/22,

32%). None of the parents of an adolescent with

cognitive impairment believed that the child would

ever be able to manage their own health.

Figure. Responses of study adolescents about their self-perceived competency in managing their disability

Table 3. Summary of responses of study parents about their self-perceived competency in managing the disability

Discussion

The present pilot study aimed to determine how

adolescents with DD and their parents in Hong

Kong accept the clinical transition and identify

the main barriers to successful transition. This was

the first step to understanding the issues of this

population group during clinical transition and to

enable planning for the future. As far as we know,

this study is the first to be conducted in Hong Kong

for this population group. Overall, 22 parents and 13

adolescents were recruited from two special schools

(one for primarily physically disabled children and

the other for severe physically and/or cognitively

impaired individuals), aiming to understand what

was the acceptance level and barriers faced by these

two vastly different groups with DD. The results

were very similar between these two subgroups,

indicating that the study parents had similar issues

during clinical transition, regardless of the type of

DD of their child. Hence, the results from these two

subgroups were discussed as one group.

Most of the study participants were aware of

the clinical transition necessary at the age of 18 years.

Only 10 (45%) of the 22 families shifted to the adult health service, despite the fact that their adolescent child

was close to or over 18 years old (Tables 1 and 2). The

reasons for this delay were not thoroughly explored

but it has been suggested that medical practitioners

in the paediatric service felt that the adolescents were

not ready for the transition so they continued to see

them well into adulthood while the parents and the

adolescents were reluctant to make the move.11 The

latter appeared to be true because when asked, most

study participants did not want to change and move

to the adult health service. This contradicts the results of

a previous local study of adolescents with chronic

medical conditions, in which over 80% of the study

participants (adolescents and parents) were willing

to move to the adult health service.11 The difference is likely

due to the complexity of the health conditions of

the present cohort. Adolescents with DD usually

have varying degrees of physical and/or cognitive

impairment and so depend more on others for

managing their health condition, making them and

their carers more anxious about any change.6 7 For

those with chronic medical conditions, the physical

and cognitive abilities of the adolescent were

unlikely affected and hence the adolescents could

manage their condition more independently and

more readily after the transition.13 This speculation

was supported by the findings about self-perceived

competency level. Most study adolescents, who

had mainly physical disabilities, were not confident

about attending a medical appointment alone

because of their limited physical abilities (Fig). The

reluctance for change may also be due to fear of

the unknown and of not being well prepared.11 In

Hong Kong, clinical transition is non-structured and

unplanned.11 Parents are often informed just before

the transition, leading to poor preparation and

confusion. Early and continuous clinical transition

from early adolescence can enable parents and

adolescents with DD to be prepared and actively

participate in the transition planning.7 14 Although

the clinical transition service is not well-known in

Hong Kong, the study participants had a positive

attitude towards a clinical transition service to help

them navigate the process by bridging the paediatric

and adult health services. In addition, the study parents

wished to have more information about available

adult health services, eg rehabilitation services, wheelchair

maintenance services, etc. More information

about the unknown has been shown to reduce the

reluctance of parents and adolescents to change and

to further improve their confidence about moving to

adult care.5 6 15 16

Another barrier was dissatisfaction with the

health care system and service providers in the

adult setting (Table 2), and is in line with present

literature.7 Some parents found it difficult to arrange

transport to the adult hospital for follow-up while

most of the appointments were currently at the

special school. More accessible public transport

might help, especially in Hong Kong, where private

vehicles are not a common option. Flexible visiting

hours in the adult hospital that would enable parents

to care for their dependent adolescent child may also

reduce their dissatisfaction. Longer waiting times

for medical appointments in the adult setting was

frequently mentioned by the study parents. In the

adult sector, patients with all kinds of neurological

conditions, both child-onset and adult-onset, are

reviewed in the same clinic. The number of patients

attending the clinic is vastly increased compared

with the paediatric setting. In addition, patients

with adult-onset neurological conditions and their

family may not understand the characteristics of DD.

Stressed behaviour of an adolescent child with DD

may be perceived by other families as impatience.

In the paediatric clinic, where all clinic attendees

were children or adolescents with DD and their

parents, the waiting time was shorter. Families as

well as clinic staff had a full understanding of DD

and would be more tolerant. It is likely that this lack

of support in the adult setting further discouraged

the study parents to make the transition willingly.

Changes to the existing health care system, such

as a separate clinic for child-onset DD conditions,

may be a possible small step to assist this group

in making a smooth transition. Education about

clinical transition for staff in both the paediatric and

adult settings allows them to prepare the families in

advance. Education about paediatric conditions and

communication with adolescents with DD can also

equip adult staff with confidence so they develop a

strong rapport with the families.16

Interestingly, from the perspective of

the adolescents, the four adolescents who had

transitioned stated that they were happy with the

adult health service. Two (50%) adolescents indicated that

because the ‘new’ doctors did not know them well,

they paid more attention to them and one adolescent

did not give any reason to support his statement. It is

likely that in the paediatric sector, these adolescents

had been followed up from early childhood by the

same medical staff who virtually watched them grow

up. A change of scene and people in the adult sector

is welcomed by these adolescents. In addition, they

might welcome the idea that they have started to

actively participate in the consultation as a ‘patient’,

unlike in the paediatric sector, where the consultation

was directed at their parents, not them.14

Parents of adolescents who had physical and/or cognitive impairment had a similar perception of

their adolescent child, that they would never be able

to attend a medical appointment alone, presumably

because of their disability (responses to questions 9

to 10 in Table 3). None of the parents of a cognitively

impaired adolescent child believed their child to

be capable of explaining their medical condition

to others or making an independent medical

decision. On the contrary, parents of a physically

disabled child thought that while it may not apply at

present, their child would be able to make their own

decisions in future (responses to questions 11 to 14

in Table 3). Nonetheless, there was a discrepancy in

this perception between the study adolescents and

parents (Fig and Table 3). Most adolescents believed

they could explain their condition to others (question

2 in the Fig) and over half believed that they could

make an independent medical decision at the time

of the study (question 7 in the Fig). Further studies

are needed to determine whether this discrepancy is

due to confusion on the part of the parents because

of changing responsibilities during the transition.13

While western literature emphasises the importance

of active participation by adolescents during clinical

transition,14 it would be interesting to see if this can

be endorsed in a parent-dominant Chinese society

such as Hong Kong, where cultural differences may

influence attitudes towards clinical transition.17

We were unable to analyse other challenges

identified in overseas literature, such as unclear

eligibility criteria and procedures and limited time

for clinical transition, because comparable data were

not available for Hong Kong. In other developed

countries, adolescents are shifted with the assistance

of a clinical transition service based in the children’s

hospital (if any) or by applying clinical guidelines for

best service.18 In Hong Kong, adolescents are referred

from the paediatric section to the adult section

within the same hospital. Each hospital cluster may

have different procedures for this ‘transition’ and

there is no defined department within the hospital

structure to assist adolescents and their families

through this process. Nor do the families receive any

advice about how to negotiate this process. A future

in-depth study is recommended to understand the

existing situation of clinical transition in different

hospital clusters and determine how to establish a

more formal approach among all the hospital clusters

in Hong Kong to support this group of adolescents

and their families during this confusing time.

Limitations of the present study

There may have been a selection bias in the

study sample as the families were approached

by convenience through the school staff. Due to

the small sample size, no statistical analysis was

conducted to compare the subgroups of adolescents

with physical and cognitive impairments. Although

the sample size was small, the purpose of the present

pilot study was not to generalise the findings to all

adolescents with DD but to begin to understand

the acceptance of clinical transition and the main

barriers to success for adolescents with DD and

their family in Hong Kong. The present results are

also in line with the literature in this area.4 7 11 14 17

Future studies with a larger sample size and more

in-depth qualitative data are required to verify the

present results. The potential subjective bias of the

results, especially for the open-ended questions, was

another limitation but we attempted to minimise

this through consensus agreement among the team.

Conclusions

In the present explorative study, close to half of the

study families had a delayed clinical transition to the

adult health service. Most study parents were reluctant for

their adolescent children to shift to the adult health service

due to unwillingness to change and dissatisfaction

with the adult medical service. A structured and

well-planned clinical transition was urged by the

study participants to bridge the paediatric and

adult health services and to provide support to the family.

Further studies are required to analyse the needs and

concerns of adolescents with DD and their families

as well as the service providers in the adult medical

setting to facilitate the future development of a

clinical transition service in Hong Kong.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participating

families from the Hong Kong Red Cross John F Kennedy Centre

and Haven of Hope Sunnyside School.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Westbom L, Bergstrand L, Wagner P, Nordmark E. Survival

at 19 years of age in a total population of children and

young people with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol

2011;53:808-14. Crossref

2. Public Law 98-527, Developmental Disabilities Act of 1984.

3. Staff J, Mortimer JT. Diverse transitions from school to

work. Work Occup 2003;30:361-9. Crossref

4. Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, et al. Transition from

child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents

with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society

for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health 1993;14:570-6. Crossref

5. American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy

of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus

statement on health care transitions for young adults with

special health care needs. Pediatrics 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1304-6.

6. Bindels-de Heus KG, van Staa A, van Vliet I, Ewals FV,

Hilberink SR. Transferring young people with profound

intellectual and multiple disabilities from pediatric to adult

medical care: parents’ experiences and recommendations.

Intellect Dev Disabil 2013;51:176-89. Crossref

7. Stewart D, Stavness C, King G, Antle B, Law M. A critical

appraisal of literature reviews about the transition to

adulthood for youth with disabilities. Phys Occup Ther

Pediatr 2006;26:5-24. Crossref

8. Persons with disabilities and chronic diseases in Hong

Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Census and Statistics

Department; 2016. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B71501FB2015XXXXB0100.pdf. Accessed Jul

2016.

9. Clusters, hospitals & institutions. Hospital Authority.

2016. Available from: http://www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_index.asp?Content_ID=10036&Lang=ENG&Dimension=100&Parent_ID=10004. Accessed Jul 2016.

10. Hospital Authority Statistical Report 2012-2013. Hong

Kong: Hospital Authority; 2013.

11. Wong LH, Chan FW, Wong FY, et al. Transition care for

adolescents and families with chronic illnesses. J Adolesc

Health 2010;47:540-6. Crossref

12. Hong Kong Society for Adolescent Health. Adolescent

Transition Care Assessment Tool, Public Education Series

No. 12 (2013). Available from: http://hksah.blogspot.hk/2013/11/adolescent-transition-care-assessment.html.

Accessed 6 Feb 2016.

13. Stewart DA, Law MC, Rosenbaum P, Willms DG. A

qualitative study of the transition to adulthood for youth

with physical disabilities. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr

2002;21:3-21. Crossref

14. Viner RM. Transition of care from paediatric to adult

services: one part of improved health services for

adolescents. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:160-3. Crossref

15. Blum RW. Introduction. Improving transition for

adolescents with special health care needs from pediatric

to adult-centered health care. Pediatrics 2002;110(6 Pt

2):1301-3.

16. Stewart D. Transition to adult services for young people

with disabilities: current evidence to guide future research.

Dev Med Child Neurol 2009;51 Suppl 4:169-73. Crossref

17. Barnhart RC. Aging adult children with developmental

disabilities and their families: challenges for occupational

therapists and physical therapists. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr

2001;21:69-81. Crossref

18. Department of Health. National Service Framework for

Children, Young People and Maternity Services. Transition:

getting it right for young people. Improving the transition

of young people with long term conditions from children’s

to adult health services. 2006. Available from: http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/8742/1/DH_4132145%3FIdcService%3DGET_FILE%26dID%3D23915%26Rendition%3DWeb. Accessed Jul

2016.