Hong Kong Med J 2016 Oct;22(5):420–7 | Epub 19 Aug 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164853

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Seatbelt use by pregnant women: a survey of knowledge and practice in Hong Kong

WC Lam, MPH (CUHK), FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1;

William WK To, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1;

Edmond SK Ma, MD, FHKAM (Community Medicine)2

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, United Christian Hospital,

Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

2 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr WC Lam (lamwc2@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The use of motor vehicles is common

during pregnancy. Correct seatbelt use during

pregnancy has been shown to protect both the

pregnant woman and her fetus. This survey aimed to evaluate the practices, beliefs, and knowledge of Hong Kong pregnant women of correct seatbelt use, and identify factors leading to reduced compliance and inadequate knowledge.

Methods: A self-administered survey was completed

by postpartum women in the postnatal ward at

the United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong, from

January to April 2015. Eligible surveys were available

from 495 women. The primary outcome was the

proportion of pregnant women who maintained or

reduced seatbelt use during pregnancy. Secondary

outcomes were analysed and included knowledge

of correct seatbelt use, as well as contributing factors to non-compliance

and inadequate knowledge.

Results: There was decreased compliance with

seatbelt use during pregnancy and the decrease was

in line with increasing gestation. Pregnant women’s

knowledge about seatbelt use was inadequate and

only a minority had received relevant information.

Women who held a driving licence and had a higher

education level were more likely to wear a seatbelt

before and during pregnancy. Women with tertiary

education or above knew more about seatbelt use.

Conclusions: Public health education for pregnant

women in Hong Kong about road safety is advisable,

and targeting the lower-compliant groups may be

more effective and successful.

New knowledge added by this study

- There was decreased compliance with seatbelt use by pregnant women in Hong Kong. The decrease in compliance became more pronounced as gestation increased. This may be related to lack of relevant information and misconceptions.

- As a form of public health and road traffic safety promotion, information about seatbelt use during pregnancy should be provided to pregnant women, health care workers, and all road traffic users.

Introduction

Road traffic safety is an important public health issue.

Health care professionals are usually involved in the

treatment of road traffic accident victims rather than

prevention of their occurrence or minimising the

severity of injury. Education about and promotion

of road traffic safety is important for all; pregnant

women are no exception. Safety issues relate to both

the mother and her fetus, and different information

and/or a different approach may be required. With

any kind of intervention during pregnancy, an

emphasis on the safety of the fetus may improve

compliance.

The number of pregnant drivers in Hong Kong

is unknown, but the use of motor vehicles including

private car, taxi, and public light bus is common

during pregnancy. To promote maternal seatbelt use

among the local pregnant population, information

about their beliefs is essential.

Correct seatbelt use during pregnancy has

been shown to protect both the pregnant woman and

her fetus. There is evidence that pregnant women

who do not wear a seatbelt and who are involved in a

motor vehicle accident are more likely to experience

excessive bleeding and fetal death.1 2 3 Compliance

and proper use of the seatbelt are crucial. Incorrect

placement of the seatbelt and a subsequent accident

may result in fetal death due to abruptio placentae.4

The three-point restraint (ie shoulder harness in

addition to a lap belt) provides more protection

for the fetus than a lap belt alone. Previous studies

have revealed incorrect positioning of the seatbelt

in 40% to 50% of pregnant women.5 6 Various other

studies have shown reduced seatbelt compliance

during pregnancy.7 The proportion of seatbelt use

has been reported to be around 70% to 80% before

pregnancy, but reduced by half at 20 weeks or more

of gestation.5 7 There is also evidence that pregnant

women lack information about the proper use of a

seatbelt and its role in preventing injury: only 14%

to 37% of pregnant women received advice from

health care professionals.5 6 7 8 The common reasons for

not using a seatbelt have been reported to include

discomfort, inconvenience, forgetfulness, and fear of

harming the fetus.9

In this study, the current practice and

knowledge of Hong Kong pregnant women about

seatbelt use was surveyed, and any determining

factors were identified. The results will enable public

health education and promotion to be targeted to

at-risk groups to improve road traffic safety among

local pregnant women.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional survey using a convenient

sampling carried out from January to April 2015.

A self-administered questionnaire was distributed

to postpartum women in the postnatal ward of

United Christian Hospital (UCH) in Hong Kong.

Participation in the survey was entirely voluntary.

Questionnaires were analysed if at least

50% of questions were answered, including the

main outcomes. Those from women who did not

understand the content or who did not understand

Chinese or English were excluded.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was based on a pilot study, with

questions revised after review. It was available in

English and Chinese (traditional and simplified)

versions and was divided into four parts. The first part

included demographic and pregnancy information

and driving experience. The second part focused on

practice of seatbelt use before and during pregnancy,

any change in habit with progression of pregnancy,

and the reason(s) for non-use of a seatbelt. The third

part related to awareness and knowledge of the Road

Traffic Ordinance on seatbelt use and the correct

use of both lap and shoulder belts. Text descriptions

and diagrams of different restraint positions were

provided. The correct way is to place the lap belt

below the abdomen and the shoulder belt diagonally

across the chest. The diagram of restraint positions

were adopted from the leaflet “Protect your unborn

child in a car” by the Transport Department of

Hong Kong with permission.10 The final part asked

whether the postpartum woman had received any

advice about seatbelt use during pregnancy, the

source of information, and whether they thought

such information was useful and/or relevant.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation

Using the results of overseas studies as reference,

the sample size was calculated according to the

assumption that around 80% of Hong Kong pregnant

women use a seatbelt. A previous questionnaire

survey among postpartum women at a local hospital

indicated that a response rate of approximately 80%

could be expected.11 We assumed the margin of error

that could be accepted to be 4%, with a confidence

level of 95%, and using this formula: n = z2 x p x (1-p)/d2 (where p = proportion of wearing seatbelt [0.8]; d = margin of error [0.04]; and z value = 1.96), the adjusted sample size was 481.

All statistical analysis was performed using

PASW Statistics 18 (Release Version 18.0.0; SPSS

Inc, Chicago [IL], US). For categorical data, the

Chi squared test was used to compare knowledge

about seatbelt use in wearers and non-wearers. For

continuous data with a highly skewed distribution,

non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney U test for two

groups and Kruskal-Wallis H test for more than

two groups) was used to compare the knowledge of

correct seatbelt use. Knowledge score was calculated

based on the answer to questions about the Road

Traffic Ordinance on seatbelt use and the proper way

to use both the lap and shoulder belts. One point was

given for each correct answer. The critical level of

statistical significance was set at 0.05.

The relative effects of factors (age, marital

status, education level, resident status, husband’s

occupation, family monthly income, respondent’s

and husband’s driving licence holder status,

frequency of public transport use, and stage of

pregnancy) that might influence seatbelt use

during pregnancy were estimated using generalised

estimating equation (GEE). The outcome variables

were dichotomous correlated responses (eg use of

seatbelt in different gestations), and the outcome

variables were assumed to be independent. The

issue about statistical significance due to lack of

independence was corrected using GEE.

To account for the interdependence of

observations, we used robust estimates of variance

(GEE) by including each period of observation as a

cluster. For use of a seatbelt before and during each

trimester of pregnancy, since the responses were

correlated as time progressed, the GEE model with

working correlation matrix was adopted.12

Results

Demographic data

There were 769 postpartum women in the postnatal

ward during the study period. A total of 550

questionnaires were distributed by convenience and

the response rate was 91% with 501 questionnaires

returned. The remaining women (n=49, 9%)

either refused to participate or did not return the

questionnaire. Among the returned questionnaires,

six were excluded due to missing information on

the main outcomes of the survey or they were <50%

complete. At the end of the recruitment period, 495

(90%) questionnaires were valid for analysis.

The majority (93.5%) of respondents were

aged between 21 and 40 years. Only 10 (2%) were

English speakers; others (98%) spoke Cantonese

or Mandarin as their first language and completed

the Chinese questionnaire. With regard to

education level, 188 (38%) women had received

tertiary education or above, 290 (58.6%) secondary

education, and 14 (2.8%) primary education. There

was no existing information about any association

between pregnant woman or spousal occupation and

compliance with or knowledge about seatbelt use.

We therefore investigated whether occupation was

a relevant factor, for example, driver and health care

worker. Around half (n=216, 43.6%) of the women

were housewives, 57 (11.6%) were professionals, and

14 (2.8%) were medical health care workers. Among

spouses, 32 (6.5%) were drivers, two (0.4%) were

medical health care workers, and 122 (24.6%) were

professionals. Other occupations were unrelated

to transportation or health care, including clerk,

construction site worker, restaurant waiter, and

chef. Overall, 439 (88.7%) women were Hong Kong

residents, others were new immigrants or double-entry

permit holders from Mainland China. Of

the respondents, 477 (96.4%) women had attended

regular antenatal check-ups, and 215 (43.4%) were

first-time mothers.

Driving experience and mode of transport

Around half of the spouses (49.1%) but only 71 (14.3%)

women held a Hong Kong driving licence. Among

those women with a driving licence, only 16 (22.5%)

drove daily, and seven (9.9%) only at weekends.

Public transport was used daily by 300 (60.6%)

women. Among different means of public transport,

buses (53.7%) were the most commonly used but not

all seats on buses have seatbelts. In public light buses

and taxis, use of a seatbelt, if available, is mandatory:

38.6% and 15.2% of respondents used public light

buses and taxis, respectively.

Use of a seatbelt before and during pregnancy

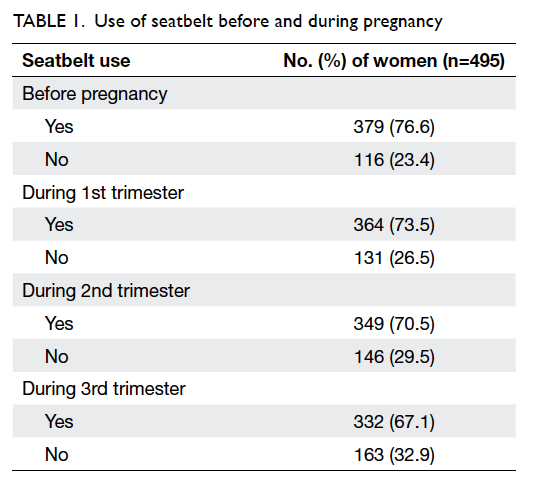

Of the respondents, 379 (76.6%) pregnant women

reported using a seatbelt in the 6 months before

pregnancy, but compliance was reduced as pregnancy

progressed. Seatbelt use was reduced to 73.5% in the

first trimester, 70.5% in the second trimester, and

67.1% in the third trimester (Table 1). There were

26 women who changed their behaviour from not

wearing a seatbelt prior to pregnancy to wearing

one after they became pregnant. Therefore the total

number of ever seatbelt users was 405. Analysis of the

knowledge score was performed by excluding these

26 women; the result showed a similar finding and

statistical significance.

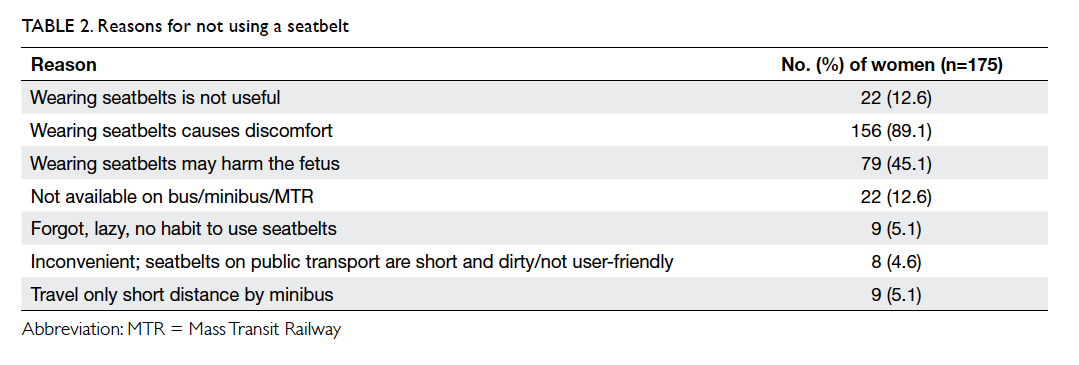

Reasons for not using a seatbelt during pregnancy

With regard to the reasons for not using a

seatbelt at any time during pregnancy, 156 (89.1%) of 175

women stated that the seatbelt caused discomfort,

22 (12.6%) thought seatbelts were not useful, and 79

(45.1%) worried that they would cause harm to the

fetus (Table 2). Apart from the three stated options

in the questionnaire, several respondents stated that

the travelling distance was usually short on public

light buses and the time taken to buckle up and

unfasten the seatbelt may delay other passengers.

Other women admitted to being lazy or forgetful, or

were just not in the habit of using a seatbelt. They

also found seatbelts inconvenient because those on

public transport were “not user-friendly”, “too short”,

or were “dirty” (Table 2).

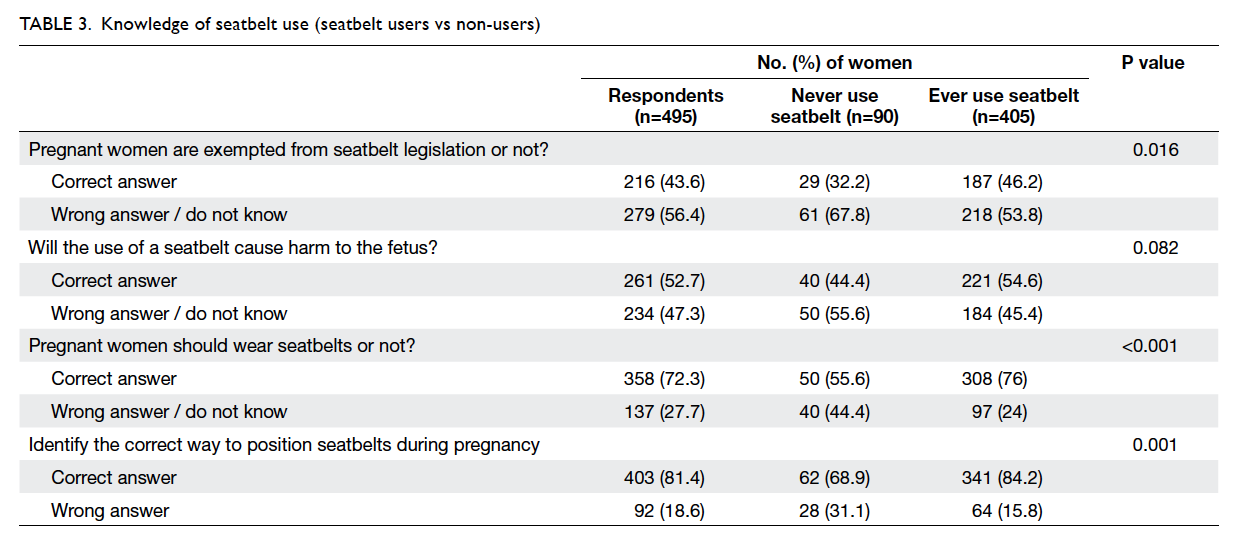

Knowledge of seatbelt use during pregnancy

Of the respondents, 216 (43.6%) correctly answered

that pregnant women are not exempted from seatbelt

use according to the Road Traffic Ordinance. The

remaining 56.4% either answered wrongly or did

not know the answer. Approximately 52.7% women

correctly pointed out that appropriate use of a

seatbelt will not harm the fetus. Although around

half of the women wrongly believed that pregnant

women are exempted from seatbelt legislation or

that use of a seatbelt will harm the fetus, 358 (72.3%)

stated that pregnant women should wear a seatbelt.

When the three-point seatbelts were shown on the

diagrams, 403 (81.4%) women could identify the

correct way of wearing the seatbelt with the lap strap

placed below the bump, not over it (Table 3).

Among all the respondents, 90 (18.2%)

women never wore a seatbelt, and the other 405

(81.8%) were seatbelt users either before or during

pregnancy. Comparison of responses revealed that

never wearers of a seatbelt had significantly poorer

knowledge in three of the four questions about

seatbelt use during pregnancy (P<0.05) [Table 3].

Information about seatbelt use during pregnancy

Information about seatbelt use had been received by

only 32 (6.5%) women. Among them, 13 (40.6%) had

derived the information from the internet, others from

staff of a government and private clinic, magazine,

and publications of Transport Department. Seven

(21.9%) received information from friends or family

members; one had a car accident during pregnancy

and was given relevant information by health care

workers at the Accident and Emergency Department.

Most (n=426, 86%) women expressed the view that

information about seatbelt use during pregnancy was

useful and necessary.

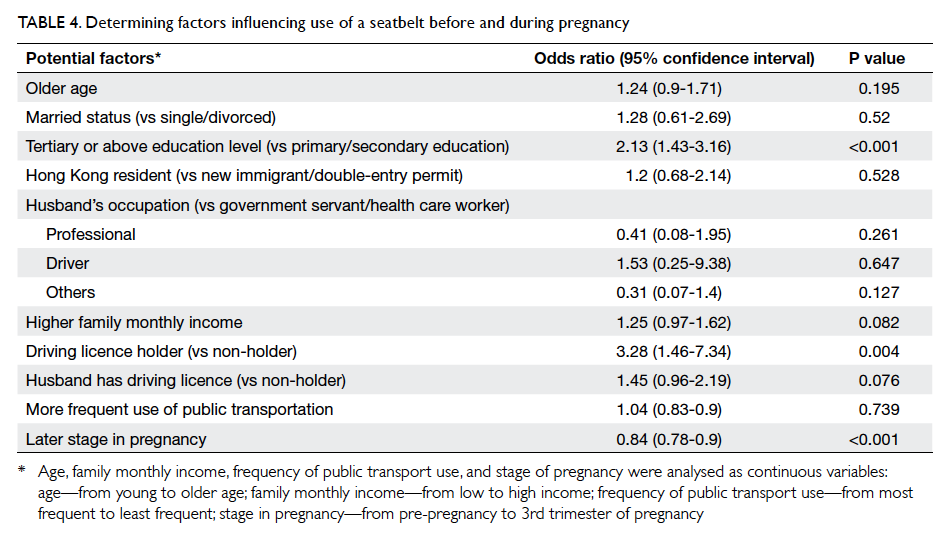

Factors influencing use of seatbelt during pregnancy

Among all potential factors, women who held a

driving licence (odds ratio [OR]=3.28; P=0.004) or

had a higher level of education (OR=2.13; P<0.001)

were more likely to use a seatbelt. Considering

time as another variable, as pregnancy progressed

women were significantly less likely to use a seatbelt

(OR=0.84; P<0.001) [Table 4].

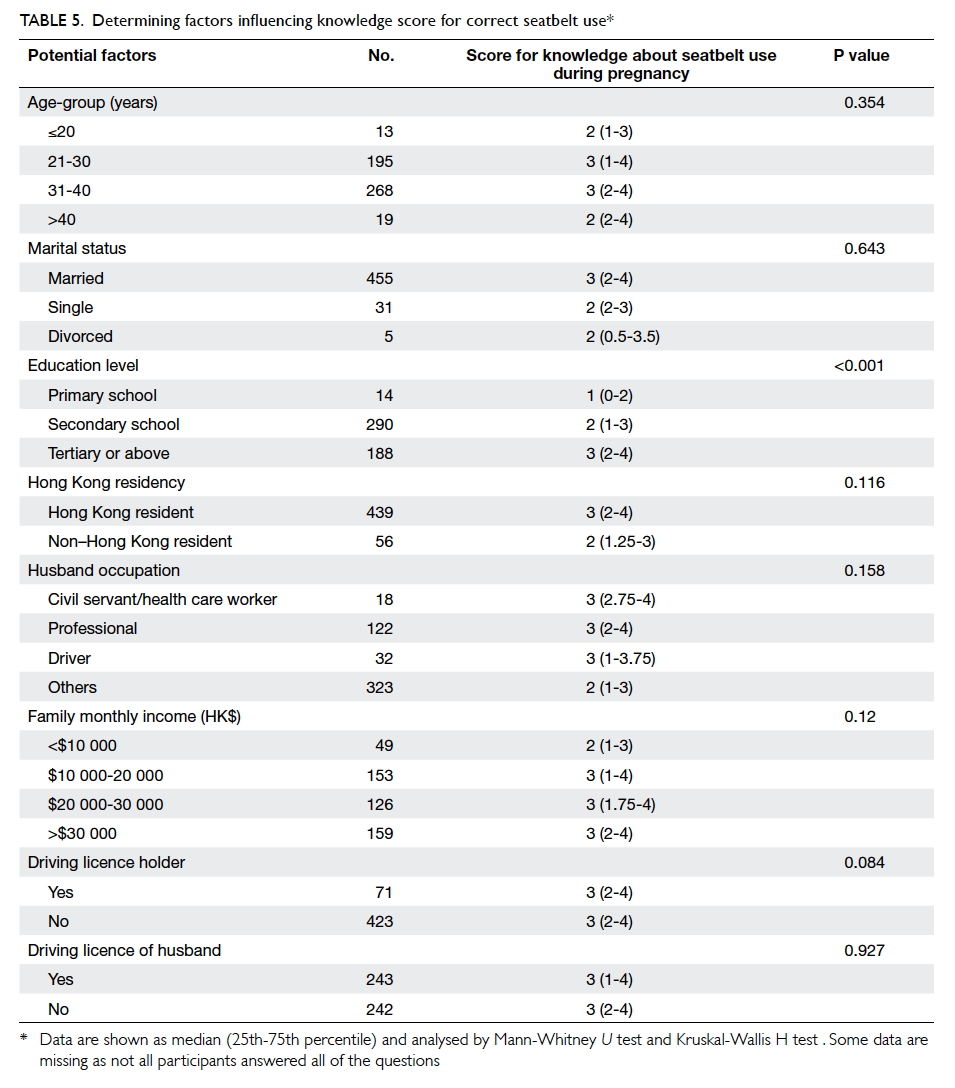

Factors influencing knowledge about correct seatbelt use

Women with a lower education level (P<0.001)

were less aware of the Road Traffic Ordinance on

seatbelt use, the protective effects of a seatbelt

during pregnancy, and the correct way to position

both the lap and shoulder belts (Table 5).

Discussion

Main findings

In this study, 76.6% of Hong Kong

pregnant women were consistent seatbelt wearers

before pregnancy; this is similar to overseas studies

which reported 70% to 80%.5 7 Compliance was

reduced during all trimesters, and decreased as

gestation progressed. Only 26 women changed their

behaviour from non-users to users after becoming

pregnant. It also demonstrated the misconception

about the effects of seatbelt use on pregnancy and

the fetus. Pregnant women’s knowledge about seatbelt use

was inadequate and only a minority had

received relevant information. Women who held

a driving licence or had a higher education level

were more likely to wear a seatbelt before and during

pregnancy. Women with a tertiary education or

above were more knowledgeable about seatbelt use.

Strengths and limitations

As far as we know, this is the first survey in Hong Kong

of the knowledge of pregnant women about seatbelt

use and their associated practice, with a reasonably

high response rate. One limitation of the study was

that the questionnaire was not validated and there

were overlapping categories for numerical variables.

Results and experience in this study can serve to

revise the questions for a future study with improved

validity and reliability. During the study period, 769

postpartum women stayed in the postnatal ward and

495 (64%) completed questionnaires were collected.

The proportion included was relatively high, but

still the method of convenient sampling may have

affected the representativeness of the sampled

subjects. Moreover this was a single-centre survey

in the obstetric unit of a district hospital. The UCH

provides obstetric services to the population in the

Kowloon East region. The geographical location of a

clinic could dictate the mode of travelling to attend

antenatal hospital appointments. Although taxis and

public light buses are the usual mode of transport,

some women may have taken the bus or Mass Transit

Railway, and these do not require use of a

seatbelt. Furthermore, the delivery rate at UCH was

less than 10% of the total deliveries in Hong Kong,

therefore the results may not be applicable to other

clusters with patients of different education levels,

driving experience, and transportation habits.

In addition, those who were unable to read or

understand Chinese or English were excluded. These

were usually illiterate or non–Hong Kong residents,

and may be the group with the lowest compliance and poorest knowledge about seatbelt use.

There were 49 women who refused to participate

and six who did not complete the questionnaire; this

10% also introduced inaccuracy and bias in our data.

Reporting bias is another concern. Discrepancies

between observed and self-reported seatbelt use

were found in a previous study.13 Anonymity of the

questionnaires might have minimised reporting

bias. Although all demographic variables included

in the questionnaire were analysed, there were other

potential confounders that might have affected the

knowledge score and the use of a seatbelt during

pregnancy. These were not investigated and hence

not adequately adjusted in the knowledge score

analysis or in the GEE model, for example prior

traffic accidents in the respondents and their family

members, risk-taking behaviours such as smoking,

alcohol drinking, and drug use. Finally, multivariate

instead of univariate analysis of the factors affecting

knowledge score could be performed to investigate

the relationship among different variables.

Interpretation

Prevention plays a major role in ensuring maternal

and fetal survival in road traffic accidents. Motor

vehicle crashes are responsible for severe maternal

injury and fetal loss. Despite existing knowledge

about the protective effects of wearing a seatbelt,

pregnant women remain poorly compliant. This

was confirmed in this local survey and in overseas

studies.14 15

In the Report on Confidential Enquiries into

Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom 1994-1996

published by the Royal College of Obstetricians

and Gynaecologists, 13 pregnant women died as a

result of road traffic accidents. One of the victims

did not use a seatbelt and was forcibly ejected from

the vehicle.16 Ten years later, in a more recent Report

on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in

the United Kingdom 2006-2008,17 there were 17

pregnant women who died as a result of road traffic

accidents. A specific recommendation was made in

the report: “All women should be advised to wear a

3-point seat belt throughout pregnancy, with the lap

strap placed as low as possible beneath the ‘bump’

lying across the thighs and the diagonal shoulder

strap above the ‘bump’ lying between the breasts.

The seat belt should be adjusted to fit as snugly and

comfortably as possible, and if necessary the seat

should be adjusted”.17

According to the Road Traffic Ordinance

in Hong Kong, drivers and passengers must wear

seatbelts where provided. The exceptions are when

reversing a vehicle, making a three-point turn,

manoeuvring in and out of a parking place, and

those who have a medical certificate and have been

granted an exemption on medical grounds by the

Commissioner for Transport.18 According to a report

of the Transport Department of Hong Kong, the total

number of road traffic accidents was 14 436 in 2003.

In 2013, the number rose to 16 089. The number

of pregnant women involved or injured in road

traffic accidents is unknown.19 The Hong Kong SAR

Government revises seatbelt legislation regularly to

enhance road safety. Since 1 January 2001, passengers

have been required to wear a seatbelt, if available,

in the rear of taxis as well as in the front. Since 1

August 2004, passengers on public light buses have

also been required to wear a seatbelt where one is

fitted.20 21 Stickers were put inside buses and taxis to remind passengers of their responsibility to wear a

seatbelt and to give clear instructions on the correct

way to wear it. Nonetheless, the requirement to use

a seatbelt and its protective effects were not well

recognised among the respondents in this survey.

This may be due to the lack of information provision

as only 6.5% of women had received information

related to seatbelt use in pregnancy.

In this study, those with a lower education

level had poorer knowledge about seatbelt use in

pregnancy. Effective public education should target

these women. Using diagrams as instruction can

be simple and direct so that those with a lower

education level or who only use public transportation

occasionally can easily understand and follow the

advice. In the past, leaflets or stickers about seatbelt

use were widely seen, especially after introduction

of the new legislation, but those specifically targeted

to the pregnant population were not common.

Maternal child health centres and antenatal clinics

of government hospitals are ideal places to distribute

educational material. Television announcements

may also convey the message effectively, not only

to pregnant women, but to all road traffic users. It

is also a good opportunity to inform drivers and

other passengers so that they can help pregnant

women as well as the elderly and disabled who use

public transport. Regular spot-checks on public

transport and law enforcement may also encourage

compliance with seatbelt use. The majority of

doctors and midwives give advice about seatbelt

use only if asked. This survey demonstrated that the

proportion of pregnant women who received seatbelt

information was very small. It is recommended that

written instructions and advice should be available

from well-informed health care professionals, and

pregnant women should always be encouraged to

wear a correctly positioned seatbelt. Obstetricians,

midwives, and general practitioners play an

important role in disseminating information. A study

in Ireland showed that 75% of general practitioners

believed women should wear seatbelts in the third

trimester, although only 30% provided regular advice

and fewer than 50% indicated that they were aware

of the correct advice to give.22

Conclusions

This study demonstrated decreased compliance

with seatbelt use during pregnancy that continued

to decrease as pregnancy progressed. Women with

a lower education level or without a driving licence

were less likely to use a seatbelt during pregnancy.

The former were also less aware of the Road

Traffic Ordinance on seatbelt use and the correct

way to position both the lap and shoulder belts.

Only a minority of pregnant women had received

information about seatbelt use. Future studies to

assess the knowledge of Hong Kong health care

workers about use of seatbelts in pregnancy may

enhance the awareness and involvement of medical

professionals in educating pregnant women on this

issue. Publicity and education about road safety

by health care providers and the government are

advised, and targeting the lower compliant groups

may be more effective and successful.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Mr Edward

Choi for his valuable statistical advice, the staff in

the postnatal ward of UCH for helping to collect

the questionnaires, and the Transport Department

of Hong Kong for permission to use the diagram of

restraint positions adopted from the leaflet “Protect

your unborn child in a car” on the questionnaires.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Hyde LK, Cook LJ, Olson LM, Weiss HB, Dean JM. Effect

of motor vehicle crashes on adverse fetal outcomes. Obstet

Gynecol 2003;102:279-86. Crossref

2. Wolf ME, Alexander BH, Rivara FP, Hickok DE, Maier

RV, Starzyk PM. A retrospective cohort study of seatbelt

use and pregnancy outcome after a motor vehicle crash. J

Trauma 1993;34:116-9. Crossref

3. Klinich KD, Schneider LW, Moore JL, Pearlman MD.

Injuries to pregnant occupants in automotive crashes.

Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med 1998;42:57-91.

4. Bunai Y, Nagai A, Nakamura I, Ohya I. Fetal death from

abruptio placentae associated with incorrect use of a

seatbelt. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2000;21:207-9. Crossref

5. Jamjute P, Eedarapalli P, Jain S. Awareness of correct use of a

seatbelt among pregnant women and health professionals:

a multicentric survey. J Obstet Gynaecol 2005;25:550-3. Crossref

6. Johnson HC, Pring DW. Car seatbelts in pregnancy: the

practice and knowledge of pregnant women remain causes

for concern. BJOG 2000;107:644-7. Crossref

7. Ichikawa M, Nakahara S, Okubo T, Wakai S. Car seatbelt

use during pregnancy in Japan: determinants and policy

implications. Inj Prev 2003;9:169-72. Crossref

8. Taylor AJ, McGwin G Jr, Sharp CE, et al. Seatbelt use

during pregnancy: a comparison of women in two prenatal

care settings. Matern Child Health J 2005;9:173-9. Crossref

9. Weiss H, Sirin H, Levine JA, Sauber E. International survey

of seat belt use exemptions. Inj Prev 2006;12:258-61. Crossref

10. Transport Department, The Government of the Hong Kong

Special Administrative Region. Protect your unborn child

in a car. Available from: http://www.td.gov.hk/filemanager/en/content_174/belt-e.pdf. Accessed Aug 2016.

11. Yu CH, Chan LW, Lam WC, To WK. Pregnant women’s knowledge and consumption of long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplements. Hong Kong J Gynaecol Obstet Midwifery 2014;14:57-63.

12. Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using

generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13-22. Crossref

13. Robertson LS. The validity of self-reported behavioral risk factors: seatbelt and alcohol use. J Trauma 1992;32:58-9.Crossref

14. Luley T, Fitzpatrick CB, Grotegut CA, Hocker MB, Myers

ER, Brown HL. Perinatal implications of motor vehicle

accident trauma during pregnancy: identifying populations

at risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208:466.e1-5. Crossref

15. Grossman NB. Blunt trauma in pregnancy. Am Fam

Physician 2004;70:1303-10.

16. Chapter 13: Fortuitous deaths. Why mothers die: report on

confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United

Kingdom 1994-1996. London: Royal College of Obstetrics

and Gynaecologists Press; 2001.

17. Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, et al. Saving

Mothers’ Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make

motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the

Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United

Kingdom. BJOG 2011;118 Suppl 1:1-203. Crossref

18. Transport Department, The Government of the Hong

Kong Special Administrative Region. Be Smart, buckle

up. Available from: http://www.td.gov.hk/filemanager/en/content_174/seatbelt_leaflet.pdf. Accessed Aug 2016.

19. Transport Department, The Government of the Hong

Kong Special Administrative Region. Road Traffic Accident

Statistics Year 2013. Available from: http://www.td.gov.hk/en/road_safety/road_traffic_accident_statistics/2013/index.html. Accessed Aug 2016.

20. Transport Department, The Government of the Hong

Kong Special Administrative Region. Seat belt: safe

motoring guides. Available from: http://www.td.gov.hk/en/road_safety/safe_motoring_guides/seat_belt/index.html.

Accessed Aug 2016.

21. Transport Department, The Government of the Hong

Kong Special Administrative Region. Road Safety Bulletin;

March 2001. Available from: http://www.td.gov.hk/filemanager/en/content_182/rs_bulletin_04.pdf. Accessed

Aug 2016.

22. Wallace C. General practitioners knowledge of and

attitudes to the use of seat belts in pregnancy. Ir Med J

1997;90:63-4.