Hong Kong Med J 2016 Jun;22(3):256–62 | Epub 6 May 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154736

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection at

a low-volume centre: tips and tricks, and learning

curve in a district hospital in Hong Kong

Deon HM Chong, FRCSEd;

CM Poon, FRCSEd;

HT Leong, FRCSEd

Department of Surgery, North District Hospital, Sheung Shui, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr HT Leong (lamyn@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Colorectal endoscopic submucosal

dissection is not a widely adopted procedure due to

its technical difficulties. This study aimed to share

the experience in setting up this novel procedure and

to report the learning curve for such a procedure at a

low-volume district hospital in Hong Kong.

Methods: This case series comprised 71 colorectal

endoscopic submucosal dissections that were

performed by a single endoscopist without

experience in gastric or colorectal endoscopic

submucosal dissection. Lesion characteristics,

procedure time per unit area of tumour, en-bloc

resection rate, R0 resection rate, complications, and

length of stay were recorded prospectively. Results

were compared for two consecutive periods to study

the learning curve.

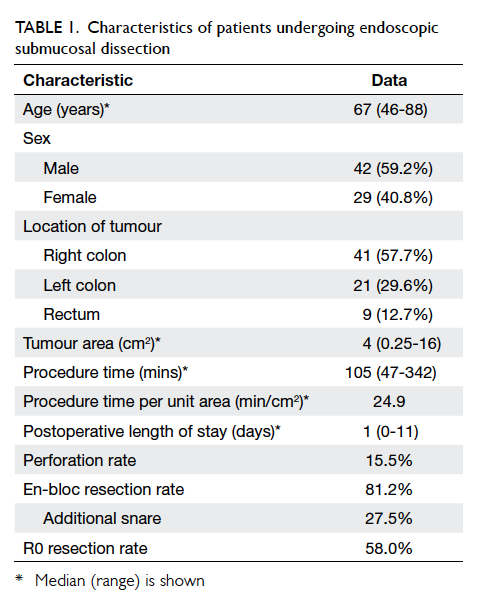

Results: Overall, 41 (57.7%) tumours were located

in the right colon, 21 (29.6%) in the left colon, and nine

(12.7%) in the rectum. The median tumour area was

4 cm2 (range, 0.25-16 cm2). The median operating

time was 105 (range, 47-342) minutes. The median

procedure time per unit area of tumour was 24.9

min/cm2. There was one instance of intra-operative

bleeding that required conversion to laparoscopic

colectomy. There was no postoperative haemorrhage.

The overall perforation rate was 15.5%, in which one

required conversion to laparoscopic colectomy. The

overall morbidity rate was 16.9% and there was no

mortality. The median hospital stay was 1 day (range,

0-11 days). The overall en-bloc resection rate and R0

resection rate was 81.2% and 58.0%, respectively.

Comparison of the two study periods revealed that

procedure time per unit area of tumour decreased

significantly from 31.5 min/cm2 to 21.5 min/cm2

(P=0.032). The en-bloc resection rate improved

from 78.8% to 83.3% (P=0.15). The R0 resection rate

improved significantly from 39.4% to 75.0% (P<0.01).

Conclusion: Untutored colorectal endoscopic

submucosal dissection is feasible with acceptable

clinical outcomes at a low-volume district hospital

in Hong Kong.

New knowledge added by this study

- Untutored colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has an acceptable clinical outcome after 35 procedures at a low-volume centre.

- ESD can be safely performed at a low-volume centre.

- ESD can be started at the colorectum instead of the stomach.

Introduction

For many years, conventional endoscopic mucosal

resection (EMR) and surgery were the only options

for treating a large (>20 mm) sessile or flat colorectal

lesion. Conventional EMR, however, often results in

piecemeal removal and there is a significant local

recurrence rate ranging from 7.4% to 17%.1 2 3 Full

histological evaluation is also difficult.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD),

pioneered in Japan for treating early upper

gastro-intestinal malignancy, was introduced in

the late 1990s by Yamamoto et al4 and Fujishiro et

al5 to treat colorectal lesions. The technique has

an advantage over EMR in that its effectiveness

is not limited by size or shape of the lesion. In the

past decade, colorectal ESD has been shown to

be superior to EMR, in terms of higher en-bloc

resection rate and lower recurrence rate.6 Colorectal

ESD can be applied not only to adenoma, but also

to intramucosal carcinoma and low-risk submucosal

carcinoma, as defined by the Paris classification7

and the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon

and Rectum.8 Recently, a large-scale multicentre study has shown that ESD alone is adequate in the

management of patients with low-risk submucosal

carcinoma and achieves an excellent 5-year

recurrence-free survival of 98% and 5-year overall

survival of 94%.9

Despite the growing evidence to support

the use of colorectal ESD, it is not established as a

standard treatment outside Japan. The drawbacks of

colorectal ESD include longer operating time6 and

higher complication rates, especially perforation.

Although the perforation rate of ESD is much

higher than that of EMR, most ESD perforations

can be treated conservatively by clip closure

during endoscopy.10 11 In a multicentre study of iatrogenic perforations in Japan, the respective EMR and ESD perforation rate was 0.58% and 14% in 15 160 therapeutic colonoscopies.12 Endoscopic

clipping failed in 43.5% of ESD perforations and

surgical intervention was necessary.12

Perhaps one of the major hurdles to its general

application is that it is a technically demanding

procedure that is difficult to set up at a low-volume

district hospital. We would like to share

our experience of applying this novel technique in a

district hospital in Hong Kong.

Methods

Case selection

North District Hospital was a district hospital

serving 700 000 population with a case volume of 15

to 20 cases of ESD per year. Since the introduction of

the ESD technique at the hospital in 2009, all lateral

spreading tumours larger than 2 cm or those unable

to be resected en bloc by conventional polypectomy

were referred to a single endoscopist to determine

the appropriateness of ESD. Colonoscopy was

repeated by a single endoscopist to determine the

location, size, and nature of each tumour by white-light and narrow band imaging (NBI). Benign

polyps not amendable to removal by EMR were

triaged to ESD. Target biopsy was performed on

Sano III lesions that were triaged to conventional

laparoscopic colectomy. No tumours were excluded

based on location.

Preoperative evaluation of the depth of invasion

Evaluation of the depth of invasion is important

to determine the treatment strategy. To predict

the depth of invasion, we used NBI colonoscopy,

based on Sano’s capillary pattern classification. The

underlying principle is that angiogenesis is critical

for transition of a premalignant lesion to a malignant

one and the microcapillary pattern changes in this

process. Sano et al13 focused on this microcapillary

difference based on their histopathological findings

and devised three classifications: types I, II, and III.

Type III was further subdivided into IIIA and IIIB.14

The diagnostic accuracy of NBI colonoscopy

in differentiating a neoplastic from non-neoplastic

lesion is superior to conventional colonoscopy

and equivalent to chromoendoscopy using indigocarmine.15 For estimation of the depth of invasion, the sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy

of capillary pattern type III for differentiating

pM-ca (intramucosal) or pSM1 (superficial) from pSM2-3 (deep) was 84.8%, 88.7% and

87.7%, respectively.14 We preferred NBI colonoscopy

because it is fast and easy to use, without the need to

spray dye as in chromoendoscopy.

Preparation

The procedure was performed in the operating

theatre with the patient under conscious sedation.

All patients were assessed by an anaesthetist in a

preoperation clinic.

Patients were instructed to eat a low-residue

diet 2 days before the procedure and a fluid diet

on the day before ESD. Bowel preparation with

4 L polyethylene glycol solution was given on the

day before ESD. Prophylactic antibiotics were not

prescribed.

Setting

All procedures were performed in the operating

theatre. This ensured that all equipment was on

hand should conversion to an open procedure be

required, for example, if there was full-thickness

perforation that could not be closed endoscopically.

Endoscopic system

In our hospital, ESD was performed using a single-channel colonoscope (CF-H180AL; Olympus,

Tokyo, Japan). This colonoscope was a high-density

television compatible with a wide angle of 170°,

3.7-mm instrument channel, and auxiliary water

jet. A short transparent hood was fitted to the tip of

the endoscope so that the whole ring could be seen

in endoscopic view. Carbon dioxide was used for

insufflation to decrease patient discomfort. We used

a high-frequency electrosurgical generator (ESG-100; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a peristaltic pump

(AFU-100; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The energy

setting used for incision and dissection was “forced

coagulation 2” 30W, whereas “soft coagulation”

100W was used for haemostasis.

Cutting devices

In our initial practice, we used the Flex Knife (KD-630L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) to perform the procedure. It had a loop-shaped tip that allowed

easy control in any direction, as it was soft and

flexible. Nonetheless, we found it difficult to

adjust the length of the tip and there was frequent

accumulation of debris around the tip. We then

changed to Dual Knife (KD-650L; Olympus, Tokyo,

Japan) with a fixed length (1.5 mm) and hence a

more stable knife movement. More recently, we

have used Flush Knife BT (DK2618JB/DK2618JN;

Fujifilm, Saitama, Japan) for dissection. It has a

ball tip of fixed length that touches a wider part of

tissue and enhances haemostasis. The knife has a

water jet channel and achieves two purposes: (1) it

can wash away any tissue that accumulates around

the tip, thereby maintaining the sharpness of the

knife; and (2) submucosal normal saline injection

can be performed without the need to change the

instrument for further hyaluronate injection.

Injecting agent

We used a mixture of 10% sodium hyaluronate (LG

Chemical, South Korea) and 1:200 000 adrenaline

saline at a ratio of 1:1.5. This solution was chosen for

three reasons: the addition of adrenaline can produce

a haemostasis effect; dilution of sodium hyaluronate

made it less viscous and thus easier to inject; and

it reduced the amount used of the relatively more

expensive sodium hyaluronate.

Endoscopist

All ESD procedures were performed by a single

experienced endoscopist who had performed more

than 500 therapeutic colonoscopic procedures and

more than 200 laparoscopic colectomies. The ESD

procedure was implemented by the endoscopist

following completion of training on an animal model

in the Second Master Workshop on Novel Endoscopic

Technology & Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection

in 2009 at Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong,

which was organised by the Department of Surgery,

The Chinese University of Hong Kong (http://www.surgery.cuhk.edu.hk/events/2009-07-22-ESD.pdf). The workshop included both lecture sessions and hands-on sessions to perform ESD in a pig. The

endoscopist had no experience in gastric or

colorectal ESD. He received further overseas training

in ESD in 2011 at Osaka Medical Center for Cancer

and Cardiovascular Diseases in Japan as a clinical

observer with hands-on animal model training.

Procedure

With the patient initially lying in the left lateral

position, a full colonoscopy was first performed to

confirm and locate the site of pathology. Patients

were then re-positioned such that the lesion was

at an anti-gravitational position in the endoscopic

view at 6 o’clock. This could be easily achieved by

seeing the injected water pooling opposite to the

lesion. In this position, the gravitational force aided

in retracting the lesion away from the submucosal

plane during dissection. We then injected 1:100 000

adrenaline saline at 1 cm distal to the lesion, aiming

at the submucosal layer. This could be ascertained by

seeing the formation of a dwell. With the injecting

needle still in situ, the solution was then changed to the

mixture of adrenaline saline and sodium hyaluronate

to provide a precipitous elevation of sufficient height.

After elevating the lesion, a mucosal incision was

made proximal to the lesion. The mucosal incision

was started at the proximal two thirds of the lesion.

After mucosal incision, the submucosal plane was

dissected with the submucosa dissected away from

the muscle layer. Care was taken to manipulate the

dissection plan parallel to the intestinal wall to prevent

perforation. When a more than 1-mm diameter vessel

was detected, it was coagulated using haemostasis

forceps (Radial Jaw 4; Boston Scientific, US). When

the flap was sufficient for retraction, the mucosal

incision was completed. In case of perforation, the

defect was closed with endoscopic clipping (EZ Clip;

Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The resected area was not

closed as healing usually occurred in a few weeks

without complications.16

Histological assessment

All specimens were pinned on a piece of foam

and fixed in formalin. Histological type, depth of

invasion, as well as lateral and vertical resection

margins were recorded. En-bloc resection was

defined as one-piece resection of an entire lesion as

observed endoscopically. R0 resection was defined

as clear lateral and vertical resection margin.

Post–endoscopic submucosal dissection

All patients were allowed to resume a full diet on the

same day. We performed no routine blood tests or

imaging and patients were discharged the next day if

there were no signs of perforation or haemorrhage.

Postoperative haemorrhage was defined as clinical

evidence of bleeding manifested by melena or

haematochezia that required endoscopic haemostasis

within 0 to 14 days of the procedure.11

Follow-up

All patients were followed up in clinic 2 weeks

later to review the pathology report. Additional

surgery would be offered in case of carcinoma with

one of the following criteria: (1) margin involved;

(2) >1 mm submucosal invasion; (3) positive

lymphovascular permeation; (4) poorly differentiated

adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, or

mucinous carcinoma; or (5) high-grade tumour

budding.17 Surveillance colonoscopy was performed

1 year after ESD.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables were described as median

and range. To study the learning curve, all patients

were grouped chronologically into two periods:

group 1 with cases 1 to 35; and group 2 with cases

36 to 71. Comparisons between non-parametric data

were done with Mann-Whitney U test, while Chi

squared test was used for categorical variables. A P

value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

From March 2009 to December 2013, a total of 71

ESDs were performed. Characteristics of the patients

are shown in Table 1.

There was one conversion to laparoscopic

colectomy due to intra-operative bleeding that could

not be controlled endoscopically (40 mm x 15 mm

tumour at the transverse colon). For perforation,

there were 11 (15.5%) perforations: eight in the colon

and three in the rectum, all were noticed during the

ESD. Endoscopic clipping was successful in 10 of the

perforations. The median number of clips used was

2 (range, 1-6). One perforation required conversion

to laparoscopic colectomy (30 mm x 5 mm tumour

at the sigmoid colon). Both laparoscopic operations

were uneventful and patients were discharged

without any surgical complications. The overall

morbidity rate was 16.9% including bleeding and

perforation and there was no mortality. The median

postoperative stay was 1 day (range, 0-11 days).

Of the 69 patients who completed the

endoscopic procedure, en-bloc resection was

successful in 56 (81.2%) patients, of whom 19

(27.5%) required additional snare (SD-210U-25,

Snare Master; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) to complete

the en-bloc resection. Conversion to piecemeal

resection by snare occurred in 14 (20.3%) patients.

In these 69 patients, the resection margin

was unclear in 15 patients as it was too close to the

cauterised edge. These, together with piecemeal

resection, were classified as R1 (29 patients in total).

R0 resection was achieved in 40 (58.0%) patients. The

histopathological diagnosis was tubular adenoma

for 26 (36.6%) tumours, tubulovillous adenoma for

28 (39.4%), villous adenoma for two (2.8%), serrated

adenoma for six (8.5%), carcinoid for one (1.4%) with

involved margin, intramucosal carcinoma for two

(2.8%), and carcinoma with submucosal invasion for

six (8.5%). The ESD procedure was considered curative

for the two patients with intramucosal carcinoma.

One patient who had submucosal carcinoma

refused further treatment because of a subsequent

diagnosis of primary lung cancer. All other patients

with submucosal carcinoma had curative interval

laparoscopic surgeries. There was no residual tumour

and no lymph node involvement found in the surgical

specimen for any of these patients. The patient with

rectal carcinoid also underwent subsequent interval

laparoscopic total mesorectal excision: the pathology

was well-differentiated carcinoid with invasion to

the muscularis propria. There was one lymph node

metastasis out of 11 lymph nodes retrieved.

Recurrence and surveillance colonoscopy

After excluding the six interval surgeries and

two conversions to laparoscopic colectomy, the

remaining 63 patients were offered colonoscopy

surveillance of whom four refused and one defaulted

from follow-up. Until August 2014, 51 patients had

undergone surveillance colonoscopy and seven

were awaiting colonoscopy. Recurrence of polyp

occurred in seven (13.7%) out of 51 patients: three

recurrences occurred after piecemeal resection,

another three recurrences occurred after additional

snare to complete the en-bloc resection. All three

cases had uncertain margin due to proximity to the

cauterised edge. In one patient, recurrence occurred

after successful en-bloc resection by ESD, in which

the deep margin was clear but the circumferential

margin was not certain.

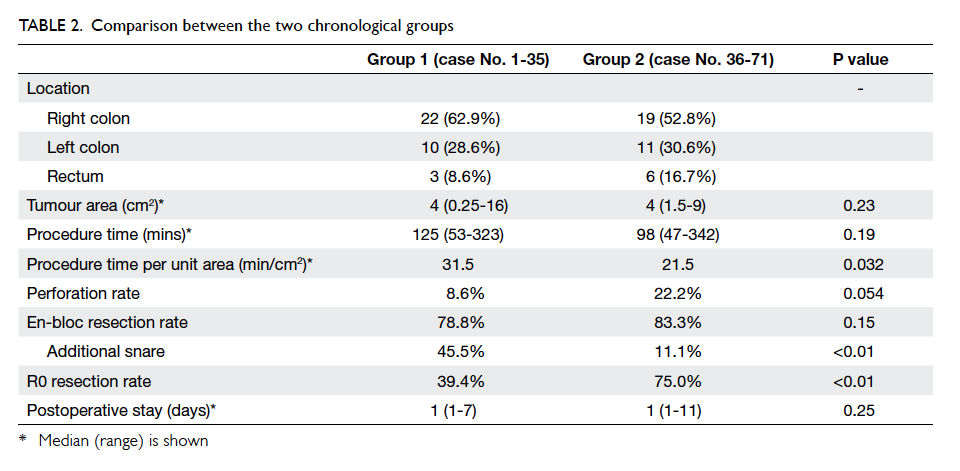

Learning curve between the two chronological groups

All patients were grouped chronologically into two

periods: group 1 with cases 1 to 35; and group 2 with

cases 36 to 71. The comparison between the two

groups is shown in Table 2. The median procedure

time per unit area of tumour improved significantly

from 31.5 min/cm2 to 21.5 min/cm2 (P=0.032).

There were three (8.6%) perforations in group

1; one of them required conversion to laparoscopic

colectomy. There were eight (22.2%) perforations

in group 2; all managed successfully by endoscopic

clipping. There was no significant difference in

perforation rate (P=0.054). The intra-operative

bleeding that required a conversion to laparoscopic

colectomy also belonged to group 1.

For the 33 patients in group 1 who completed

the endoscopic procedure, en-bloc resection was

successful in 26 (78.8%), while 30 (83.3%) out of 36

patients in group 2 had successful en-bloc resection.

This trend of improvement, however, did not reach

statistical significance (P=0.15). Among these

successful en-bloc resections, 15 (57.7%) out of 26

patients in group 1 and four (13.3%) out of 30 patients

in group 2 required additional snare to complete the

en-bloc resection (P<0.01).

R0 resection rate had improved significantly in

group 2 despite a lower rate of snare application: 13

(39.4%) of 33 patients in group 1 had R0 resection,

whereas in group 2, 27 (75.0%) of 36 patients had R0

resection (P<0.01).

The median postoperative stay was 1 day in

both groups and was not significantly different

(P=0.25). The median postoperative stay in patients

with perforation in group 1 and group 2 was 1 day

(range, 1-7 days) and 2 days (range, 1-11 days),

respectively (P=0.73).

Discussion

Colorectal ESD has been shown to be feasible and

safe when performed at expert centres in Japan.

In a recent prospective multicentre cohort study

involving 1111 patients in Japan, the reported

en-bloc resection rate was 88% and R0 resection rate

was 89%.11 The total perforation rate was only 5.3%

and postoperative bleeding was 1.5%.11 Nonetheless,

these excellent results are largely reported from

Japan. Colorectal ESD is technically difficult, as the

lumen is narrow and angulated and the very thin

wall presents a high risk of perforation. In Japan,

endoscopists are first required to gain experience

in gastric ESD, which is technically less demanding,

before they move on to colorectal ESD.18 This is not

possible in western and Asian countries outside

Japan, where early gastric cancer is much less

prevalent. In a recent review of 82 rectosigmoid

ESD from a tertiary centre in Germany, the en-bloc

resection rate and R0 resection rate was only 81.6%

and 69.7%, respectively.19 This reflects the difficulty

in generalising this novel procedure in other counties

outside Japan, and an even greater challenge to low-volume

district centres that lack local expertise.

The low case volume and the absence of expertise

in western countries leads to the development of

untutored colorectal ESD when it is impossible to

have a step-up approach in ESD training starting

from the stomach before proceeding to colon. The

reported learning curve for untutored colorectal

ESD has an acceptable outcome, however. Berr et al20 reported a case series of 48 colorectal ESDs with 76% en-bloc resection, 14% perforation, and 4%

requirement for surgical intervention. This compared

favourably with results in Japan.11 Another learning

curve study of colorectal ESD found procedure time

could be significantly shorter after 25 procedures.21

With a similar situation in Hong Kong, this

study showed that untutored colorectal ESD is

safe and feasible. Results demonstrated obvious

improvement after 35 procedures, as evidenced

by the significant reduction in combined ESD and

EMR with snare from 45.5% to 11.1%. Procedure

time per unit area of tumour as well as R0 resection

rate also significantly improved after 35 cases.

Although there were more perforations in group

2, it did not determine adverse outcome. None of

the perforations in group 2 required conversion to

laparoscopic colectomy. There was no significant

impact on hospital stay. The higher perforation

rate in group 2 may reflect a second learning curve

to perform a complete ESD procedure without

the assistance of a hybrid technique to achieve a

reasonable R0 resection rate. A perforation rate

comparable with the Japanese series11 is expected in

the third tranche of 35 patients.

Contrary to perforations in traditional

therapeutic colonoscopies, all perforations in

ESD were only 1 to 2 mm in size and were noticed

intra-operatively, thus immediate endoscopic

repair was possible. No patient required surgical

intervention solely for treatment of perforation.

The only conversion to laparoscopic colectomy in

the initial learning curve aimed to offer one-stop

treatment rather than treating perforations. In a

multicentre review of colonoscopic perforations by

Teoh et al,22 43 (0.113%) perforations were found

in 37 971 colonoscopies. Only seven (43.8%) out

of 16 therapeutic colonoscopic perforations were

noticed during the endoscopic procedure. The mean

size of perforation was 0.98 cm. The overall 30-day

morbidity and mortality rate was 48.7% and 25.6%,

respectively and the stoma rate was 38.5%. This

showed clearly that surgical outcome was much

worse in conventional colonoscopic perforations

compared with perforations in ESD, despite a much

higher perforation rate of 15.7% in ESD group.22

After implementation of the ESD service, the

following were noted:

(1) Venue of procedure—operating theatre was chosen instead of an endoscopic unit to enable conversion to conventional laparoscopic colectomy without the need to change location as well as the ready availability of an anaesthetist to give conscious sedation.

(2) Mode of anaesthesia—in the first few patients, we performed ESD under general anaesthesia for patient comfort and in the event conversion to laparoscopic colectomy was necessary. Positioning of patients was clumsy particularly when a prone position was needed to perform the procedure. Subsequently conscious sedation by an anaesthetist was used instead. Patients could follow instructions for positioning and deeper sedation could be achieved if necessary. There were no complaints from patients about any discomfort during the procedure.

(3) Choice of injecting agents—albumin 20% (Albumex 20; CSL, Australia) was used as submucosal injecting agent in the first few patients when sodium hyaluronate was not available. Albumin 20% has both a good cushioning effect without any inflammatory effect and the cost was much cheaper at HK$2.7/mL compared with commercially available sodium hyaluronate at HK$68/mL.23 Yet sodium hyaluronate has the longest lasting cushioning effect among all injecting agents. We recommend its use whenever available.

(4) A mixture of adrenaline saline and sodium hyaluronate was favourable for the assistant to inject and a lesser volume of sodium hyaluronate was required. Moreover, there were no instances of postoperative haemorrhage, although it was difficult to conclude whether this was due to the addition of adrenaline saline.

(5) Endoscopic technique—in our initial practice, we performed a full circumferential mucosal incision before submucosal dissection. We noticed it was technically more difficult compared with a two-third circumferential incision, because firstly, the submucosal elevation was lost quickly due to faster leakage of injecting agent, and secondly, it was difficult to retract the lesion at the end of dissection, and we had to complete the en-bloc resection with snare. After changing to two-third circumferential incision in the second period of the study, the need for additional snare to complete the en-bloc resection was significantly decreased (from 57.7% to 13.3%).

(6) Postoperative management—it was feasible and safe to resume diet immediately after the procedure and discharge patients the day following ESD without the need for routine blood taking or imaging. In one study from Japan, abdominal computed tomography was performed on day 1 and blood tests were carried out for 2 consecutive days. Oral intake was gradually stepped up and patients were discharged 5 days after ESD.10 In contrast, we allowed full diet on the same day after ESD and did not perform computed tomography or blood tests routinely. Our overall median postoperative stay was 1 day. Further development of ESD as a day procedure can be explored.

(1) Venue of procedure—operating theatre was chosen instead of an endoscopic unit to enable conversion to conventional laparoscopic colectomy without the need to change location as well as the ready availability of an anaesthetist to give conscious sedation.

(2) Mode of anaesthesia—in the first few patients, we performed ESD under general anaesthesia for patient comfort and in the event conversion to laparoscopic colectomy was necessary. Positioning of patients was clumsy particularly when a prone position was needed to perform the procedure. Subsequently conscious sedation by an anaesthetist was used instead. Patients could follow instructions for positioning and deeper sedation could be achieved if necessary. There were no complaints from patients about any discomfort during the procedure.

(3) Choice of injecting agents—albumin 20% (Albumex 20; CSL, Australia) was used as submucosal injecting agent in the first few patients when sodium hyaluronate was not available. Albumin 20% has both a good cushioning effect without any inflammatory effect and the cost was much cheaper at HK$2.7/mL compared with commercially available sodium hyaluronate at HK$68/mL.23 Yet sodium hyaluronate has the longest lasting cushioning effect among all injecting agents. We recommend its use whenever available.

(4) A mixture of adrenaline saline and sodium hyaluronate was favourable for the assistant to inject and a lesser volume of sodium hyaluronate was required. Moreover, there were no instances of postoperative haemorrhage, although it was difficult to conclude whether this was due to the addition of adrenaline saline.

(5) Endoscopic technique—in our initial practice, we performed a full circumferential mucosal incision before submucosal dissection. We noticed it was technically more difficult compared with a two-third circumferential incision, because firstly, the submucosal elevation was lost quickly due to faster leakage of injecting agent, and secondly, it was difficult to retract the lesion at the end of dissection, and we had to complete the en-bloc resection with snare. After changing to two-third circumferential incision in the second period of the study, the need for additional snare to complete the en-bloc resection was significantly decreased (from 57.7% to 13.3%).

(6) Postoperative management—it was feasible and safe to resume diet immediately after the procedure and discharge patients the day following ESD without the need for routine blood taking or imaging. In one study from Japan, abdominal computed tomography was performed on day 1 and blood tests were carried out for 2 consecutive days. Oral intake was gradually stepped up and patients were discharged 5 days after ESD.10 In contrast, we allowed full diet on the same day after ESD and did not perform computed tomography or blood tests routinely. Our overall median postoperative stay was 1 day. Further development of ESD as a day procedure can be explored.

There are a number of limitations in this

study. First, this was the learning curve of a single

endoscopist and 35 procedures may not be a typical

number required for such a learning curve. Second,

the inclusion criteria for colorectal ESD were less

strict than those in Japan. Lesion less than 2 cm that

could not be removed en bloc would be subjected

to ESD instead of piecemeal resection. These kinds

of lesion were expected to be easier with shorter

operating time. Third, this was a retrospective

comparison of two chronological groups which might not have been directly comparable. Lastly, the

7.9% patient default rate may lead to underestimation

of recurrence in this series.

Conclusion

Untutored colorectal ESD at a low-volume centre

was an option in the absence of enough experts to

supervise the procedure. Training on an animal

model and clinical observation of real-time

demonstrations was useful to start ESD without

supervision. A cut-off at 35 procedures showed

an acceptable R0 resection rate at a significantly

improved procedure time per unit area. There was

a second learning curve to achieve a complete ESD

procedure without EMR at a higher perforation rate.

Colorectal ESD performed by a colorectal surgeon

enables any complications to be managed by the

same operator, or any lesion unresectable by ESD to

be surgically removed. It was not necessary to first

perform gastric ESD as the start of ESD training.

When more endoscopists have gained experience

in colorectal ESD, a structured training programme

with accreditation can be established.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Tanaka S, Haruma K, Oka S, et al. Clinicopathological

features and endoscopic treatment of superficially

spreading colorectal neoplasms larger than 20 mm.

Gastrointest Endosc 2001;54:62-6. Crossref

2. Walsh RM, Ackroyd FW, Shellito PC. Endoscopic resection

of large sessile colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc

1992;38:303-9. Crossref

3. Uraoka T, Fujii T, Saito Y, et al. Effectiveness of glycerol

as a submucosal injection for EMR. Gastrointest Endosc

2005;61:736-40. Crossref

4. Yamamoto H, Kawata H, Sunada K, et al. Successful en-bloc

resection of large superficial tumors in the stomach and

colon using sodium hyaluronate and small-caliber-tip

transparent hood. Endoscopy 2003;35:690-4. Crossref

5. Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, et al. Outcomes of

endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal epithelial

neoplasms in 200 consecutive cases. Clin Gastroenterol

Hepatol 2007;5:678-83. Crossref

6. Saito Y, Fukuzawa M, Matsuda T, et al. Clinical outcome

of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic

mucosal resection of large colorectal tumors as determined

by curative resection. Surg Endosc 2010;24:343-52. Crossref

7. The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic

lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30

to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;58(6

Suppl):S3-43.

8. Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, et al. Japanese Society

for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines

2010 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol

2012;17:1-29. Crossref

9. Yoda Y, Ikematsu H, Matsuda T, et al. A large-scale

multicenter study of long-term outcomes after endoscopic

resection for submucosal invasive colorectal cancer.

Endoscopy 2013;45:718-24. Crossref

10. Yoshida N, Wakabayashi N, Kanemasa K, et al. Endoscopic

submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors: technical

difficulties and rate of perforation. Endoscopy 2009;41:758-61. Crossref

11. Saito Y, Uraoka T, Yamaguchi Y, et al. A prospective,

multicenter study of 1111 colorectal endoscopic

submucosal dissections (with video). Gastrointest Endosc

2010;72:1217-25. Crossref

12. Taku K, Sano Y, Fu KI, et al. Iatrogenic perforation

associated with therapeutic colonoscopy: a multicenter

study in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:1409-14. Crossref

13. Sano Y, Muto M, Tajiri H, et al. Optical/digital

chromoendoscopy during colonoscopy using narrow-band

image system. Dig Endosc 2005;17(Suppl):S43-8. Crossref

14. Ikematsu H, Matsuda T, Emura F, et al. Efficacy of capillary

pattern type IIIA/IIIB by magnifying narrow band imaging

for estimating depth of invasion of early colorectal

neoplasms. BMC Gastroenterol 2010;10:33. Crossref

15. Machida H, Sano Y, Hamamoto Y, et al. Narrow-band

imaging in the diagnosis of colorectal mucosal lesions: a

pilot study. Endoscopy 2004;36:1094-8. Crossref

16. Iguchi M, Yahagi N, Fujishiro M, et al. The healing process

of large artificial ulcers in the colorectum after endoscopic

mucosal resection [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc

2003;57:AB226.

17. Asano M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection and surgical

treatment for gastrointestinal cancer. World J Gastrointest

Endosc 2012;4:438-47. Crossref

18. Tanaka S, Tamegai Y, Tsuda S, Saito Y, Yahagi N, Yamano

HO. Multicenter questionnaire survey on the current

situation of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection

in Japan. Dig Endosc 2010;22 Suppl 1:S2-8. Crossref

19. Probst A, Golger D, Anthuber M, Märkl B, Messmann H.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection in large sessile lesions

of the rectosigmoid: learning curve in a European center.

Endoscopy 2012;44:660-7. Crossref

20. Berr F, Wagner A, Kiesslich T, Friesenbichler P, Neureiter

D. Untutored learning curve to establish endoscopic

submucosal dissection on competence level. Digestion

2014;89:184-93. Crossref

21. Białek A, Pertkiewicz J, Karpińska K, Marlicz W, Bielicki

D, Starzyńska T. Treatment of large colorectal neoplasms

by endoscopic submucosal dissection: a European single-center

study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26:607-15. Crossref

22. Teoh AY, Poon CM, Lee JF, et al. Outcomes and predictors

of mortality and stoma formation in surgical management

of colonoscopic perforations: a multicenter review. Arch

Surg 2009;144:9-13. Crossref

23. ASGE Technology Committee, Kantsevoy SV,

Adler DG, Conway JD, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection

and endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest

Endosc 2008;68:11-8. Crossref