Hong Kong Med J 2016 Jun;22(3):231–6 | Epub 11 Apr 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154672

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Acceptability of the combined oral contraceptive pill among Hong Kong women

Sue ST Lo, MD, FRCOG;

Susan YS Fan, MB, BS, MRCOG

The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong, 10/F, 130 Hennessy Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Sue ST Lo (stlo@famplan.org.hk)

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the motivators and barriers

to the use of the combined oral contraceptive pill

among Hong Kong women.

Methods: The Family Planning Association of Hong

Kong commissioned the ESDlife to launch an online

survey and invited its female members aged 18 to

45 years who had used contraceptives in the past

12 months to participate in this survey. The online

survey was posted on the ESDlife website between

April 2015 and May 2015. Measurements included

contraceptive choice, and motivators and barriers to

the use of a combined oral contraceptive pill.

Results: A total of 1295 eligible women with a

median age of 32 years participated in this survey.

In the past 12 months, 76.1% of them used a male

condom, 20.9% practised coitus interruptus, 16.2%

avoided coitus during the unsafe period, and 12.6%

took a combined oral contraceptive pill. These

women chose a combined oral contraceptive for

convenience, effectiveness, and menstrual regulation, though 60.9% had stopped the pills because they were

worried about side-effects, experienced side-effects,

or consistently forgot to take the pills. Some women

had never tried a combined oral contraceptive pill

because they feared side-effects, they were satisfied

with their current contraceptive method, or pill-taking

was inconvenient.

Conclusions: The combined oral contraceptive pill is

underutilised by Hong Kong women compared with

those in many western countries. A considerable

proportion of respondents expressed concern about

actual or anticipated side-effects. This suggests that

there remains a great need for doctors to dispel the

underlying myths and misconceptions about the

combined oral contraceptive pill.

New knowledge added by this study

- Some women chose a combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill for convenience, effectiveness, and menstrual regulation.

- Some women had never tried a COC pill because they feared its side-effects, were satisfied with their current contraceptive method, or pill-taking was inconvenient.

- Some women stopped taking their COC pill because they feared its side-effects, experienced side-effects, or consistently forgot to take pills.

- During contraceptive counselling, doctors should educate women and dispel the myths and misconceptions about COC pills.

- Doctors should explain the side-effects of the COC pill, its absolute risk, and the underlying health conditions that might increase the risk of complications as well as the non-contraceptive benefits of COC thoroughly so that women can make an informed decision and use it safely.

- To help women stay on the pill, doctors should inform women that different pills have slightly different side-effect profiles and they can switch to another formulation if they experience any problem with their current COC. Improving accessibility by allowing walk-in consultations for problems with the COC pill gives women additional support.

Introduction

According to the Family Planning Knowledge, Attitude and Practice in Hong Kong Survey 2012 among

Hong Kong couples,1 the male condom was the most

popular contraceptive. The proportion of couples

who used a male condom doubled from 32.2% in

1987 to 69.6% in 2012. Combined oral contraceptive

(COC) pill was the second most common form of

contraception, though the proportion of women

using a COC pill declined from 20.3% in 1987 to

10.8% in 2012. The failure rate of the male condom

when used correctly is 6 times higher than that for the

COC pill.2 Although the low-dose COC pill has a low

incidence of complications, high efficacy, and many

non-contraceptive benefits, relatively few women use

it in Hong Kong. The report of the United Nations

world contraceptive patterns 2013 estimated that

the prevalence of pill use in Hong Kong women aged

15 to 49 years was 6.7%, which is much lower than

other countries with similar development, wealth,

and culture such as Australia (30.0%), Canada

(21.0%), Singapore (10.0%), the UK (28.0%), and the US (16.3%).3 Unlike these countries, the COC pill is not a prescription drug in

Hong Kong. Women can buy a low-dose COC pill

that contains either 30-µg or 20-µg ethinylestradiol

and one of the progestogens: levonorgestrel,

gestodene, desogestrel, or drospirenone at any of the

large-chain personal health and beauty retailers or

pharmacy stores. All pills have similar efficacy. Their

failure rate is 0.3% within the first year of perfect

use.2 Low-dose pills are safer, better tolerated, and

have equal or higher efficacy than high-dose pills

that contain 50-µg ethinylestradiol.

With 70% of couples in Hong Kong using the

male condom,1 the demand for abortion due to failed

contraception cannot be ignored. It was shown that

77.4% of women who underwent an abortion were

using contraception during the index pregnancy

and 51.2% of them were using a male condom.1 The

number of legal abortions in Hong Kong has reduced

from 25 363 in 1995 to 10 359 in 2014 (personal

communication, Department of Health), though

the number of abortions carried out across the border

is unknown. According to the results from the serial

5-yearly territory-wide family planning survey,1 the

proportion of married women who went to China for

their last abortion increased from 24.3% in 1992 to

47.2% in 2012. Given the limited resources assigned

to abortion in public hospitals, women have to resort

to the more expensive legal abortion service in

private hospitals or the Family Planning Association

of Hong Kong (FPAHK). The FPAHK performs 3000

medical and surgical first-trimester abortions each

year and has reached its full service capacity. There

is a need to further reduce unplanned pregnancies

and abortion in Hong Kong. One plausible solution

is to encourage more women to use more effective

contraception such as the combined hormonal

contraceptive pill, progestogen-only contraceptives,

intrauterine contraceptive device, or sterilisation.

The failure rate of these effective contraceptives

when used correctly is <1% in the first year of use.2

Studies have shown that identifying women’s

perspective can help doctors understand their motive

to choose one contraceptive over another.4 One study

identified personal choices, local factors, women’s

perceived safety, effectiveness, and convenience of

the method as determinants of contraceptive choice.5

Among the effective contraceptives available in

Hong Kong, the COC pill is the most accepted. We

performed this survey to determine the motivators

and barriers to COC pill use.

Methods

The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong

invited ESDlife to host the survey that was open to

its female members aged between 18 and 45 years.

The questionnaire was designed by the investigators.

ESDlife is an online lifestyle media in Hong Kong.

It is a joint venture between the Hong Kong SAR

Government and a commercial firm that began in

2000 with the aim of providing e-government and

e-commerce services. With the establishment of the

Government’s own website in 2008, all government

services have migrated to the official website and

ESDlife remains a solely commercial portal. As of

2 January 2015, it had 297 152 members of whom

64.4% were female. Among the female members,

89.0% were within our target age range: 32.3% were

30-34 years old, 23.3% were 35-39 years old, 19.3%

were 25-29 years old, 10.3% were 40-45 years old,

and 3.8% were 18-24 years old.

ESDlife sent out 100 000 invitations

randomly to its female members aged between 18

and 45 years on 21 April 2015 and invited them to

participate in this online survey between 21 April

2015 and 20 May 2015. There were 16 questions that

explored the basic demographic characteristics of

respondents (6), their contraceptive choice (3), and

their motivators and barriers to COC use (7). Invited

members entered the survey via a link and those who

had not used any contraception in the previous 12

months were screened out by the first question. Only

eligible subjects could proceed with the survey. They

could stop at any question and the questionnaire

would be voided. To encourage participation, a

$50 supermarket coupon was given to every 10th

respondent via ESDlife. This study was reviewed and

approved by the Health Services Subcommittee and

Ethics Panel of the FPAHK.

Data analyses were accomplished using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows

version 22.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). Descriptive

statistics were presented. Bivariate Chi squared

test was performed to analyse the demographic

characteristics that predicted COC pill use.

Results

During the survey period, only completed

questionnaires were captured by the system so the

number of incomplete questionnaires was unknown.

A total of 1566 women completed the survey

within the 1-month period, 271 were screened out

by Question 1 because they had not used regular

contraception in the past 12 months and 1295

questionnaires were analysed. The response rate was

1.57%. The median age of the respondents was 32

years (interquartile range, 29-36 years). Half of them

(50.7%) had a university education, 20.5% had a post-secondary

education (diploma or associate degree),

and 28.3% had a secondary education. The majority

(65.5%) were married, 29.0% were unmarried,

3.3% were cohabiting, 2.1% had separated or

divorced, and 0.2% were widowed. Over half of the

respondents were nulliparous (56.7%) and had no

plan for pregnancy (52.3%). They usually purchased

contraceptives from a chain of personal health and

beauty retailers (52.8%), convenience store and

supermarket (43.9%), or pharmacy (23.6%). They

usually sought contraceptive information from

an online health website (46.5%), online forum

(40.1%), gynaecologists (27.8%), or family planning

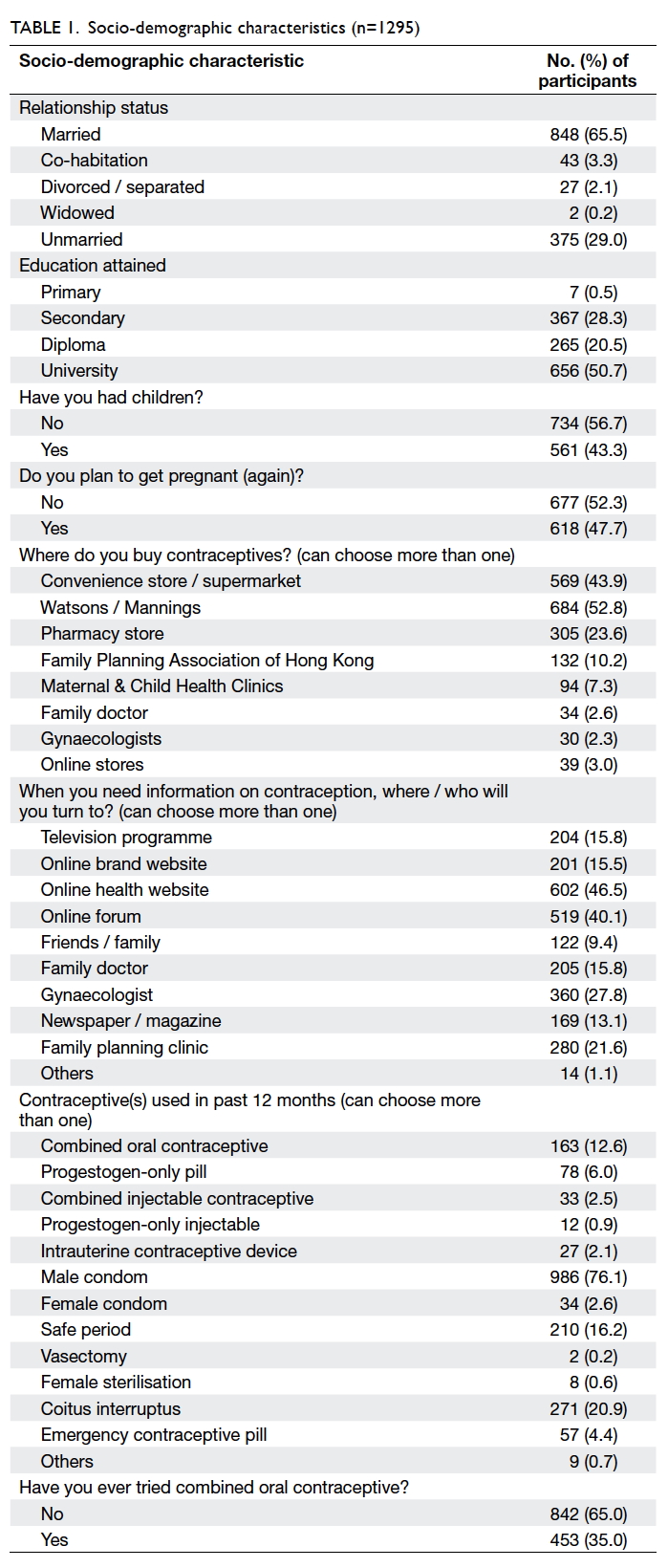

clinic (21.6%). A summary of the socio-demographic

characteristics is shown in Table 1.

Among the 1295 respondents, 453 (35.0%)

had used more than one type of contraceptive in the

previous 12 months. The contraceptive choices of

the whole group were: male condom (76.1%), coitus

interruptus (20.9%), safe period (16.2%), and COC

pill (12.6%) [Table 1]. The contraceptive choices of the 986 male condom users were further analysed

to estimate their risk of unplanned pregnancy.

Among them, 598 (60.6%) used a male condom

alone, 295 (29.9%) also used other less effective

contraceptives such as a female condom, safe period,

and coitus interruptus but whether they used them

all together during coitus or switched between

these contraceptives was unknown. Therefore,

these condom users were indisputably at risk for

unplanned pregnancy because they did not use other

effective contraceptives with the male condom.

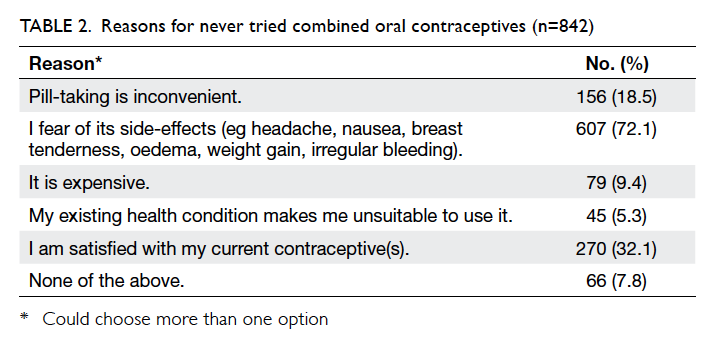

In this study sample, 842 (65.0%) women had

never tried a COC pill. The main reasons were

fear of side-effects (72.1%), satisfied with their

current contraceptive (32.1%), and pill-taking was

inconvenient for them (18.5%) [Table 2]. Among

453 women who had tried a COC pill, the median

age they started use was 24 years (interquartile

range, 20-28 years). Use of COC pill was associated

with older age (mean ± standard deviation: users and non-users was 33.4 ± 5.8 and 32.4 ±

5.5 years, respectively; t test, P=0.003), not planning to

get pregnant (P=0.002), and university education

(P=0.004). There was no association with relationship

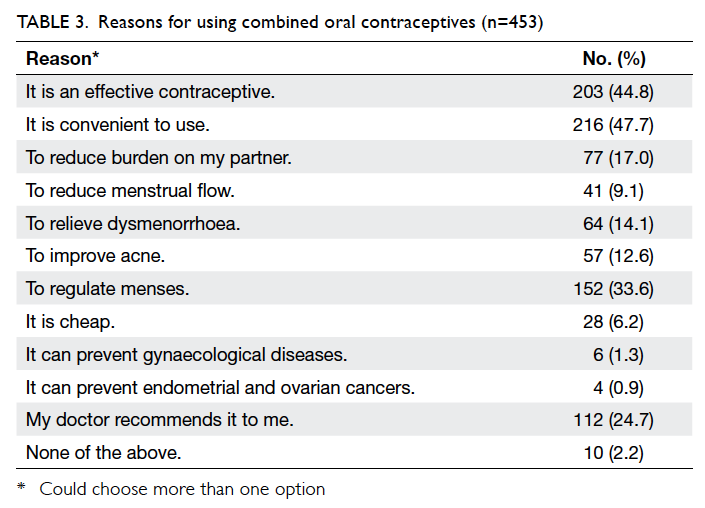

status (P=0.968) or parity (p=0.427). These women

preferred the COC pill because of convenience

(47.7%), effectiveness (44.8%), menstrual regulation

(33.6%), recommendation by their doctor (24.7%),

reduced burden to partner (17.0%), for relief of

dysmenorrhoea (14.1%), and improvement of acne

(12.6%) [Table 3]. They chose a COC pill based on

the dosage of hormones, type of hormones, and

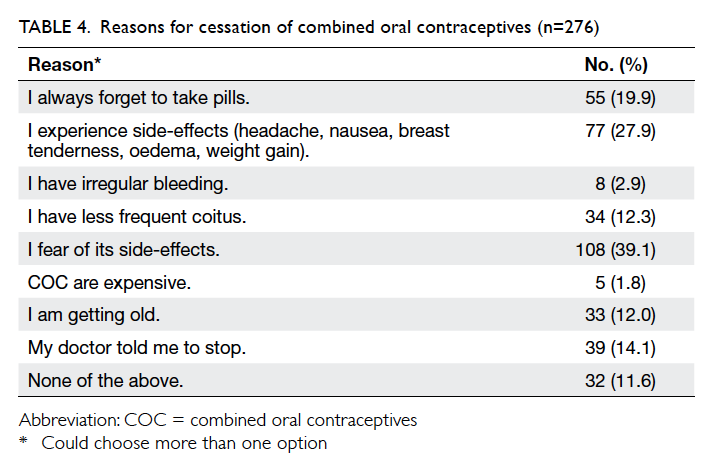

price. Among the 453 ever-users, 177 (39.1%) had

been taking a COC pill in the previous 12 months.

Use had stopped in 276 because they feared side-effects

(39.1%); they experienced side-effects such

as nausea, vomiting, breast tenderness, oedema, or

weight gain (27.9%); they consistently forgot to take

pills (19.9%); their doctor told them to stop (14.1%);

or they were having less frequent coitus (12.3%)

(Table 4).

Discussion

The pattern of contraceptive use in this study

sample was similar to that in the 2012 territory-wide

survey.1 Male condom was the most popular

contraceptive, used by 76.1% of couples in our study.

The proportion of women using a COC pill in our

study was also similar to that in the 2012 survey.

Our survey has provided some information about

the characteristics of women who chose to take the

COC pill, such as older age, university education,

and no plan for future pregnancy. A similar age

profile and education attainment were identified in

a national survey conducted in the US,6

in which parity and relationship

status were also characteristics associated with COC

pill use.

Fear of side-effects was the major reason cited

by both subgroups of women who stopped or had

never tried a COC pill. Studies carried out in both

developed and developing countries have also shown

that the experience of side-effects as well as the fear of

side-effects are major reasons for discontinuation.7 8 9 10

It appeared that fear of side-effects was a unique

barrier across different countries and cultures.

Minor side-effects such as breast tenderness, fluid

retention, nausea, and vomiting were transient and

usually subsided after one to two cycles. Major

health hazards such as myocardial infarction, stroke,

thromboembolism, breast cancer, and cervical cancer

are rare. Two meta-analyses showed a 2-fold increase

in myocardial infarction and stroke in low-dose COC

pill users compared with non-users.11 12 The risk of

venous thromboembolism was increased by 3- to

5-fold depending on the type of progestogen used.13

Since the baseline incidence of these vascular events

in women of reproductive age is very low (myocardial

infarction: 0.2 per 100 000 at age 30-34 years to 2.0 at

age 40-44 years14; stroke: 1 per 100 000 at age 30-34

years to 1.6 at age 40-44 years14; thromboembolism:

2 per 10 000 women at reproductive age15), the

absolute risk of such vascular complications is very

small. Breast cancer risk with a low-dose COC pill

is also small. A large meta-analysis of case-control

studies from 25 countries showed a modest increase

in breast cancer risk with the COC pill (relative

risk=1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.15-1.33).16

The risk of cervical cancer depends on the duration

of use. Women who used a COC pill for less than 5

years have no increased risk of cervical cancer. The

odds ratio for cervical cancer after using COC for 5 to 9

years was 2.82 (95% CI, 1.46-5.42) and 4.03 (95% CI,

2.09-8.02) for 10 years or longer.17 Cervical cancer is

largely preventable by regular cervical smears, safe

sex, as well as avoidance of smoking. The overall

morbidity and mortality associated with the low-dose

COC pill are low and most healthy women can

use it without major concerns.

The lack of access to consultation services has

exacerbated concern about side-effects, both for

women who experience them and for those who

fear them.9 At our clinics, women are counselled

about the common side-effects and complications

of the COC pill. This prevents them from panicking

when minor side-effects occur. They are also told to

stop taking the COC pill immediately and consult

a doctor if they develop signs and symptoms of a

major complication. Such counselling helps women

establish realistic expectations and they are able

to use COC safely. An information sheet detailing

side-effects and complications, warning signs and

symptoms for major complications, commonly

used drugs that interact with COC pill, and missed

pill management is given to all users. When first

prescribed, we usually provide two packs and then

review acceptability after 2 months. Women are

advised that different COC pills vary slightly in

their side-effect profile and they can change to

another formulation if they have problems. We also

offer walk-in clinics for any woman who wishes to

get contraceptive advice from nurses. The above

COC pill delivery mode conforms to the World Health

Organization recommendations.18

Apart from side-effects and complications,

women should be informed of the non-contraceptive

benefits of the COC pill, such as menstrual

regulation and relief of dysmenorrhoea; reduced

risk for endometrial, ovarian, and colorectal cancers;

lower incidence of gynaecological diseases such as

endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic

pregnancy; and improved acne and bone health. All

such information should be shared with women to

help them establish an impartial perspective on the

risks and benefits of the COC pill.

The main limitation of this survey is the very

low response rate, albeit not unexpected with online

survey. There was also selection bias as members

of an exclusive group were invited to participate.

Those who participated in the survey prompted

self-selection bias as they might be systematically

different from those who chose not to respond.

When we planned the study, we had explored other

alternatives such as face-to-face interview, phone

interview, or online survey for the general public.

Nonetheless, the first would be too expensive and

in the last two alternatives, we would be unable to

verify respondent’s age or gender. We settled with this

arrangement as it was the most convenient means to

reach our target group since ESDlife only allowed

female members aged 18 to 45 years to participate.

The demographic statistics provided by ESDlife

revealed that the education attainment and income

reported by its female members were better than

the population average. The contraceptive choice

in this group matched that of the population study

and the sample size was not small. Although the

results obtained cannot be generalised to the local

population, we believe they provide useful insight

into the reasons why women do or do not use the

COC pill. The other limitation is the number of

questions we could ask was limited by the budget. If

we had a larger budget to include more questions, we

would have explored the type of COC pill used, total

duration of use, and the switch pattern in women

who used more than one contraceptive in the

previous 12 months. Lastly, there was a discrepancy

in the number of women who were using a COC pill

in the past 12 months. For “Question 15. Are you

still on COC in the past 12 months?”, 177 responded

positively. In response to Question 7, however, only

163 chose COC pill as one of the contraceptives

they had used in the past 12 months. Some women

might have omitted COC when they selected their

contraceptives from the list provided in Question 7.

Conclusions

The COC pill remains underutilised in Hong Kong

compared with many western countries. The male

condom is the most popular contraceptive and the

proportion of women using a COC pill is one sixth of

that of women who use a male condom. A considerable

proportion of respondents expressed concerns

about actual or anticipated side-effects. Doctors

should focus on this area during contraceptive

counselling and help dispel the underlying myths and

misconceptions surrounding COC pill use. Studies

have shown that minor side-effects are transient,

major complications are rare in healthy women, and

there are many non-contraceptive benefits of the

COC pill. These facts should be emphasised during

COC counselling to help women balance the risks

and benefits of the COC pill and make an informed

choice about contraception.

Declaration

Sponsorship was provided by Pfizer Corporation

Hong Kong Limited to cover all costs incurred with

ESDlife and incentives for participants. The company

was not involved in the study design, execution, data

interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

References

1. Family Planning Knowledge, Attitude and Practice in

Hong Kong Survey 2012. Available from: http://www.famplan.org.hk/fpahk/en/template1.asp?style=template1.asp&content=info/research.asp. Accessed 6 Aug 2015.

2. Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States.

Contraception 2011;83:397-404. Crossref

3. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social

Affairs. Population Division. World contraceptive

patterns 2013. Available from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/family/worldContraceptivePatternsWallChart2013.pdf. Accessed

6 Aug 2015.

4. Heise L. Beyond acceptability: reorienting research

on contraceptive choice. In: Ravindran TS, Berer M,

Cottingham J, editors. Beyond acceptability: users’

perspectives on contraception. London: Reproductive

Health Matters; 1997: 6-14.

5. User preferences for contraceptive methods in India, Korea,

the Philippines, and Turkey. World Health Organization

Task Force on Psychosocial Research in Family Planning

and Task Force on Service Research in Family Planning.

Stud Fam Plann 1980;11:267-73.

6. Hall KS, Trussell J. Types of combined oral contraceptives

used by US women. Contraception 2012;86:659-65. Crossref

7. Ali M, Cleland J. Contraceptive discontinuation in six

developing countries: a cause-specific analysis. Int Fam

Plan Perspect 1995;21:92-7. Crossref

8. Sanders SA, Graham CA, Bass JL, Bancroft J. A prospective

study of the effects of oral contraceptives on sexuality

and well-being and their relationship to discontinuation.

Contraception 2001;64:51-8. Crossref

9. D’Antona Ade O, Chelekis JA, D’Antona MF, Siqueira AD.

Contraceptive discontinuation and non-use in Santarém,

Brazilian Amazon. Cad Saude Publica 2009;25:2021-32. Crossref

10. Larsson G, Blohm F, Sundell G, Andersch B, Milsom I. A

longitudinal study of birth control and pregnancy outcome

among women in a Swedish population. Contraception

1997;56:9-16. Crossref

11. Baillargeon JP, McClish DK, Essah PA, Nestler JE.

Association between the current use of low-dose oral

contraceptives and cardiovascular arterial disease: a meta-analysis.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:3863-70. Crossref

12. Khader YS, Rice J, John L, Abueita O. Oral contraceptives

use and the risk of myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis.

Contraception 2003;68:11-7. Crossref

13. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Statement.

Venous thromboembolism and hormonal contraception.

November 2014. Available from: http://www.fsrh.org/pdfs/FSRHStatementVTEandHormonalContraception.pdf. Accessed 6 Aug 2015.

14. Farley TM, Meirik O, Collins J. Cardiovascular disease and

combined oral contraceptives: reviewing the evidence and

balancing risks. Human Reprod Update 1999;5:721-35. Crossref

15. European Medicines Agency. Benefits of combined

hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) continue to outweigh

risks. Product information updated to help women make

informed decisions about their choice of contraception.

London, UK: EMA, 2014. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/referrals/Combined_hormonal_contraceptives/human_referral_prac_000016.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05805c516f.

Accessed 6 Aug 2015.

16. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer.

Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative

reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast

cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54

epidemiological studies. Lancet 1996;347:1713-27. Crossref

17. Moreno V, Bosch FX, Muñoz N, et al. Effect of oral

contraceptives on risk of cervical cancer in women with

human papillomavirus infection: the IARC multicentric

case-control study. Lancet 2002;359:1085-92. Crossref

18. World Health Organization. Family Planning: A Global

Handbook for Providers. 2011 edition. Available from:

https://www.fphandbook.org/sites/default/files/chap_1_eng.pdf. Accessed 6 Aug 2015.