Hong Kong Med J 2016 Jun;22(3):210–5 | Epub 22 Apr 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154602

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Is pain from mammography reduced by the use

of a radiolucent MammoPad? Local experience in

Hong Kong

Helen HL Chan, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

Gladys Lo, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

Polly SY Cheung, FCSHK, FHKAM (Surgery)2

1 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Hong Kong

Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

2 Private practice, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Helen HL Chan (chanhlh@yahoo.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Screening mammogram can decrease

the mortality of breast cancer. Studies show that

women avoid mammogram because of fear of pain,

diagnosis, and radiation. This study aimed to evaluate

the effectiveness of a radiolucent pad (MammoPad;

Hologic Inc, Bedford [MA], US) during screening

mammogram to reduce pain in Chinese patients and

the possibility of glandular dose reduction.

Methods: This case series was conducted in a private

hospital in Hong Kong. Between November 2011

and January 2012, a total of 100 Chinese patients

were recruited to our study. Left mammogram was

performed without MammoPad and served as a

control. Right mammogram was performed with

the radiolucent MammoPad. All patients were then

requested to complete a simple questionnaire. The

degree of pain and discomfort was rated on a 0-10

numeric analogue scale. Significant reduction in

discomfort was defined as a decrease of 10% or more.

Results: Of the 100 patients enrolled in this study, 66.3% of women reported at least a 10% reduction in the level of discomfort with the use of MammoPad. No statistical differences between age, breast size, and the level of discomfort were found.

Conclusion: The use of MammoPad significantly

reduced the level of discomfort experienced during

mammography. Radiation dose was also reduced.

New knowledge added by this study

- Pain and discomfort associated with mammography is reduced with the use of MammoPad.

- The glandular dose for mammography is also reduced.

- MammoPad is now used in all our patients. There are fewer complaints about pain during mammography.

Introduction

Screening mammography is the only known

scientifically proven method that can decrease the

mortality of breast cancer.1 2 Although most women

are informed of the importance of mammography, a

significant number avoid this screening procedure.

The three most common reasons given are fear of

pain, fear of the mammogram results, and fear of

radiation.

Among these three reasons, pain and discomfort

appear to be the most common, especially in

those with a poor experience.3 Although

most pain occurs during breast compression,

reducing compression by the technician had no

significant effect on the discomfort of mammography.

Studies have quoted different methods to relieve

patient anxiety and to reduce pain and discomfort

during the procedure. These included a thorough

explanation of the procedure,4 topical application

of 4% lidocaine gel to the skin of the chest before

mammography,5 self-controlled breast compression

during mammography,6 and the use of a radiolucent

pad (MammoPad; Hologic Inc, Bedford [MA], US)

during mammography.7 8 Oral acetaminophen and

ibuprofen were shown to be of no significant effect

in relieving discomfort during mammography.

Poulos and Rickard9 reported that decreasing the

compression force did not significantly reduce

discomfort.

Asian patients might have more fibroglandular

tissue in their breasts that thus appear to have a

higher density on screening mammogram. Whether

or not they experience more discomfort during

mammography is unknown. MammoPad is a soft,

compressible cushion that provides a softer and

warmer surface for taking mammography. We believe

it may improve compliance with mammography

among Asian patients. We performed a prospective

study to evaluate the effectiveness of MammoPad

used during screening mammogram to reduce pain

in Asian patients. The possibility of glandular dose

reduction was also assessed.

Methods

Between November 2011 and January 2012, a

total of 100 patients were recruited to our study.

The inclusion criteria included Chinese women

who were asymptomatic and referred for routine

breast screening. Patients prescribed regular oral

contraceptive pills and those with a family history of

breast cancer were also included in our study. There

was no age limitation. The included participants

were 32 to 70 years old, with a mean age of 49.7

(± standard deviation, 7.3) years. Women with known

breast cancer, who presented with breast lump or had

prior breast surgery, were excluded. After obtaining

informed consent, screening mammogram was

performed with the standard craniocaudal (CC) and

mediolateral oblique (MLO) views. For each patient,

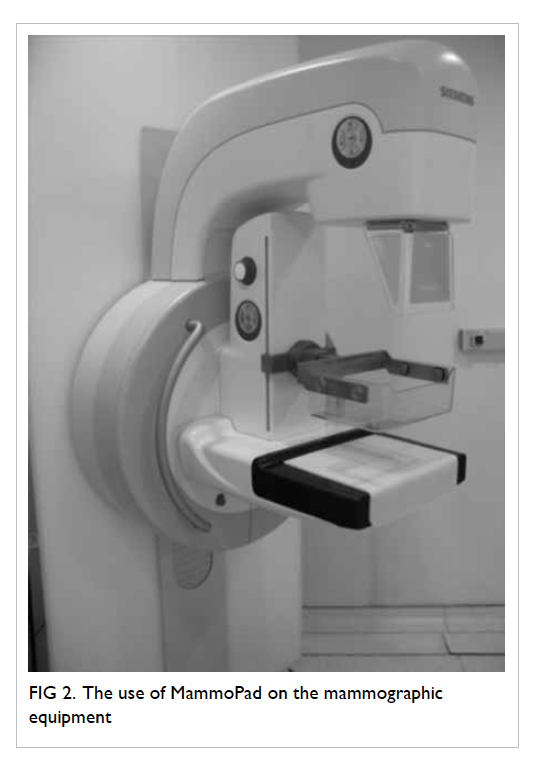

the left breast was imaged without MammoPad

and served as a control. The MammoPad was then

placed on the surface of the digital detector of the

mammographic equipment (Inspiration/Novation,

Siemens, Germany) and the right mammogram was

performed (Figs 1 and 2). The level of compression

was determined by the experienced mammographic

technician. On completion of the procedure, all

patients were requested to complete a simple

questionnaire (Appendix). The degree of pain and

discomfort (including coldness and hardness of the

mammogram compression device) was assessed by a

0-10 numeric analogue scale. Three patients refused

to participate in the study.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

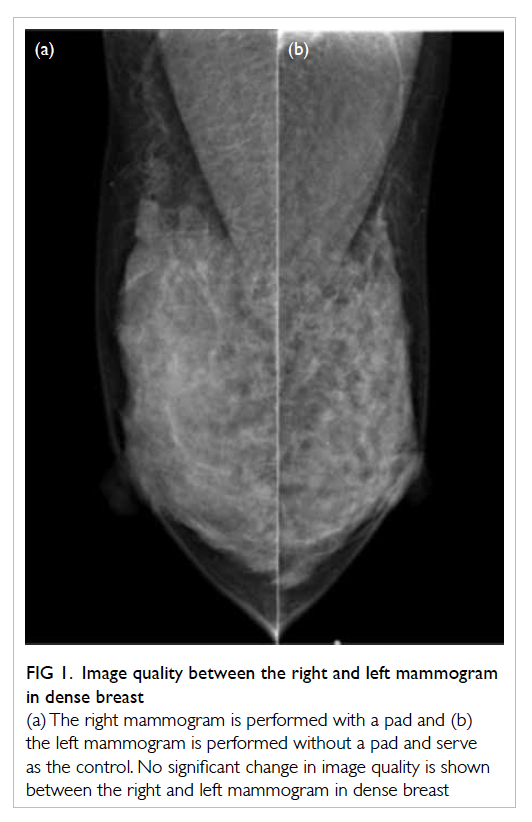

Figure 1. Image quality between the right and left mammogram in dense breast

(a) The right mammogram is performed with a pad and (b) the left mammogram is performed without a pad and serve as the control. No significant change in image quality is shown between the right and left mammogram in dense breast

The image quality of the mammograms with

and without MammoPad was assessed by two

experienced radiologists who had mammographic

training (one radiologist had >20 years of and another

radiologist >10 years of mammography reading

experience). The two radiologists were blinded as to

which side of the mammogram was performed with

and without MammoPad. Since the MammoPad

was radiolucent, its presence was not evident on the

mammogram.

The mammographic assessment was divided

into five categories:

(1) Symmetrical on both sides with satisfactory diagnostic image quality;

(2) Quality of right mammogram image slightly better than the left mammogram but with diagnostic accuracy unaffected;

(3) Quality of left mammogram image slightly better than the right mammogram but with diagnostic accuracy unaffected;

(4) Quality of right mammogram image much better than the left mammogram, affected the diagnostic accuracy, and required repeated mammogram; and

(5) Quality of left mammogram image much better than the right mammogram, affected the diagnostic accuracy, and required repeated mammogram.

(1) Symmetrical on both sides with satisfactory diagnostic image quality;

(2) Quality of right mammogram image slightly better than the left mammogram but with diagnostic accuracy unaffected;

(3) Quality of left mammogram image slightly better than the right mammogram but with diagnostic accuracy unaffected;

(4) Quality of right mammogram image much better than the left mammogram, affected the diagnostic accuracy, and required repeated mammogram; and

(5) Quality of left mammogram image much better than the right mammogram, affected the diagnostic accuracy, and required repeated mammogram.

Any disagreement about the findings was

resolved through consensus between the radiologists.

Statistical analysis

Significant reduction in discomfort of the

mammography was defined as a decrease in

discomfort by 10% or more. The mean differences

in continuous variables between the mammograms

with and without a pad were tested by paired sample

t test. The differences in the percentage of comfort

between groups in density, size, and age were tested

by Chi squared test. A two-tailed P value of <0.05

was considered statistically significant.

Results

Image quality

Among the mammograms compared, 92% of

the images from the two groups with or without

MammoPad had comparable image quality (Fig

1). Only 4% of images from the group without

MammoPad were found to have better image

quality. Another 4% of the images from the group

with MammoPad were noted to have better image

quality. In the 4% of image groups with image quality

differences (either right side better than the left side

or vice versa), two radiologists did not consider

diagnostic accuracy to be affected. The patients with

image quality differences of the right and left side

had follow-up mammograms without MammoPad

performed 1 year later. There was no mammographic

evidence of malignancy in these patients.

For pain and discomfort reduction

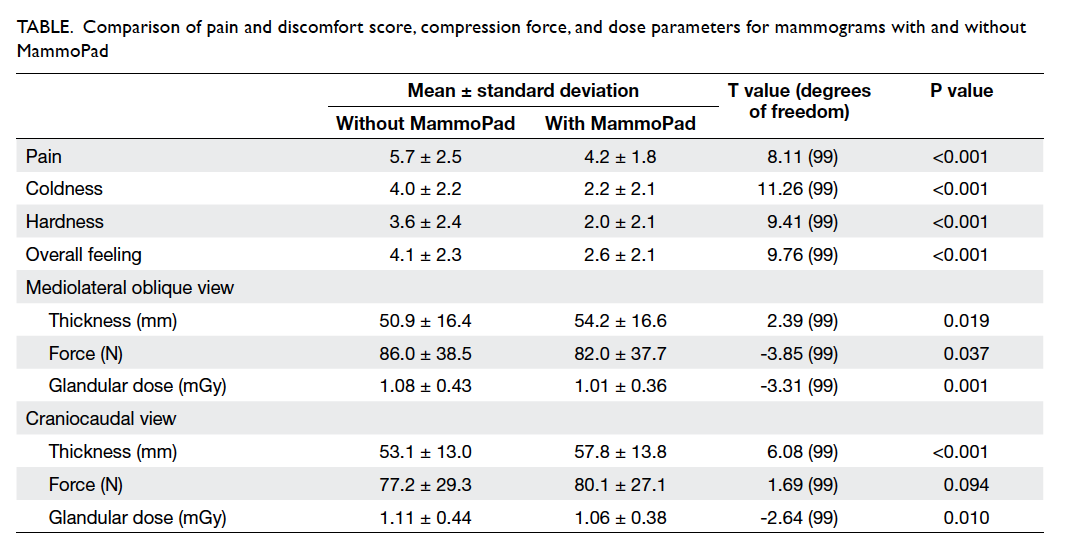

The Table shows the comparisons in pain reduction and other measures between the mammograms

with and without a pad. Using paired sample t test,

the mean (± standard deviation) scores for pain (5.7 ± 2.5 vs 4.2 ± 1.8), coldness

(4.0 ± 2.2 vs 2.2 ± 2.1), hardness (3.6 ± 2.4 vs 2.0 ±

2.1), and overall feeling (4.1 ± 2.3 vs 2.6 ± 2.1) were

significantly higher in the group without MammoPad

than the group with MammoPad (all P<0.001). The

thickness was higher in the group with MammoPad

when compared with the group without MammoPad

in both the CC view (57.8 ± 13.8 mm vs 53.1 ± 13.0

mm; P<0.001) and MLO view (54.2 ± 16.6 mm vs

50.9 ± 16.4 mm; P=0.019).

Table. Comparison of pain and discomfort score, compression force, and dose parameters for mammograms with and without MammoPad

Among the 100 patients, 90 of them had

previously undergone mammography of whom 64

(71.1%) reported the mammogram with a pad to

be ‘more comfortable’ or ‘much more comfortable’

than prior studies without a pad. Only 26 (28.9%)

patients reported that the level of discomfort for

mammogram with MammoPad was the same as

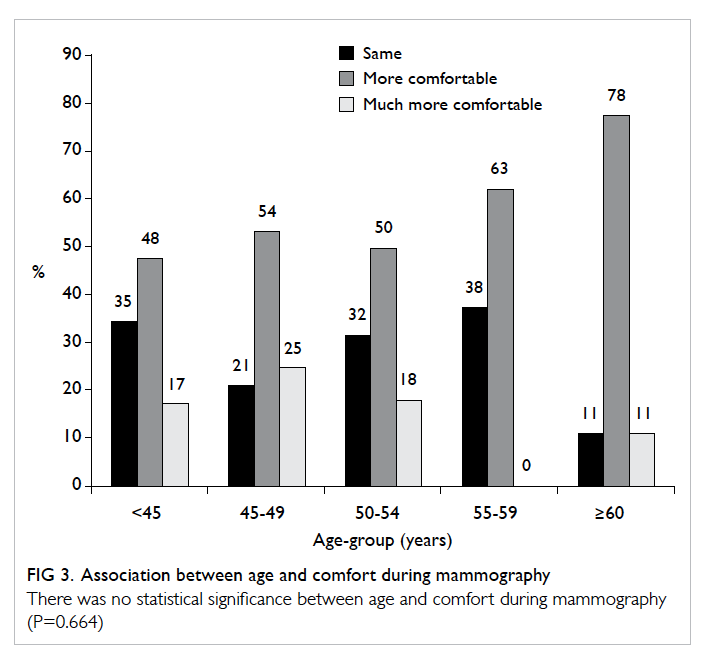

prior studies. There was no association between

patient age and comfort during mammography (Chi

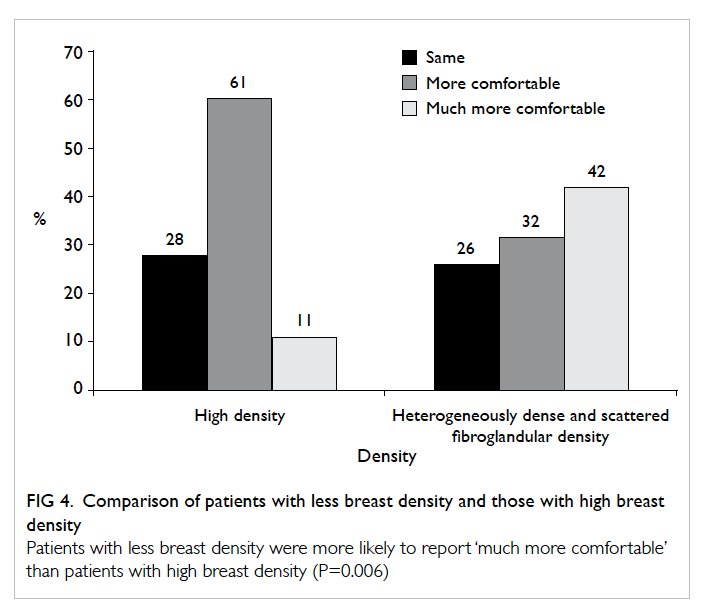

squared value=5.81, degrees of freedom [df]=8, P=0.664; Fig 3). Patients with less breast density were more likely to report

‘much more comfortable’ than those patients with

high breast density (Chi squared value=10.3 [df=2],

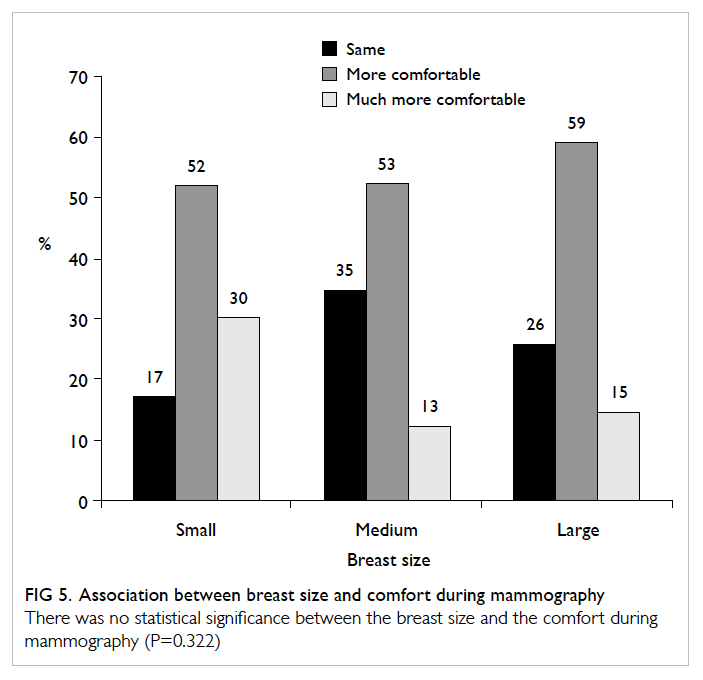

P=0.006; Fig 4). There was no statistically significant

association between breast size and comfort

during mammography (Chi squared value=4.68

[df=4], P=0.322; Fig 5). All patients preferred using

MammoPad in future mammography.

Figure 3. Association between age and comfort during mammography

There was no statistical significance between age and comfort during mammography (P=0.664)

Figure 4. Comparison of patients with less breast density and those with high breast density

Patients with less breast density were more likely to report ‘much more comfortable’ than patients with high breast density (P=0.006)

Figure 5. Association between breast size and comfort during mammography

There was no statistical significance between the breast size and the comfort during mammography (P=0.322)

For dosage reduction

The mean glandular dose was higher in the group without

MammoPad than the group with MammoPad in

both views (1.11 ± 0.44 mGy vs 1.06 ± 0.38 mGy for CC view,

and 1.08 ± 0.43 mGy vs 1.01 ± 0.36 mGy for MLO view). For the

group with MammoPad, there was a 4.5% decrease

in dose for the CC view and 6.5% decrease in dose

for the MLO view. The statistical significance was

P=0.01 and 0.001, respectively (Table).

For compression force

There was no statistically significant difference in

the mean compression force in the two groups in the CC

view (80.1 ± 27.1 N vs 77.2 ± 29.3 N; P=0.094).

Reduced compression force in the MammoPad

group was noticed in the MLO view (82.0 ± 37.7 N

vs 86.0 ± 38.5 N; P=0.037) [Table].

Discussion

Breast cancer is the third leading cause of cancer

death among females in Hong Kong, after colorectal

and lung cancers.10 In 2013, a total of 596 women

died from breast cancer, accounting for 10.5% of all

cancer deaths in females.10 Screening mammogram

is proven to be effective in the early detection of

breast cancer. Unfortunately, the utilisation of

screening mammogram in Hong Kong is limited,

partly because there is no government-subsidised

mammographic screening programme. Another

important factor is the discomfort experienced

during mammography.

Various studies have attempted to reduce the

pain and discomfort associated with mammography.

The most promising method to date appears to be

the radiolucent MammoPad. Tabar et al7 reported

that two thirds of women experienced a significant

reduction in pain when the radiolucent cushions

were used during mammography. Markle et al8

reported that use of a radiolucent cushion reduced

discomfort during screening mammogram in 73.5%

of patients.

In our study, we confirmed that the image

quality of the mammograms was unaffected by the

presence of the MammoPad. After review by the

radiologists, diagnostic accuracy was considered

unaffected in the 4% image groups with image

quality differences (either right side better than the

left or vice versa). The difference in image quality was

probably secondary to asymmetrical fibroglandular

tissue thickness in both breasts. In all, 66.3% of our patients reported at least a 10%

reduction in the level of discomfort with the use of

MammoPad. This finding was comparable with the

study performed by Tabar et al.7 In addition, there

was no obvious correlation between age, breast size,

and level of discomfort. Reduced compression force

in the group with MammoPad was noticed in the

MLO view, but not in the CC view.

Unlike the study performed by Dibble et al,11 we

encountered no problem with inadequate positioning

for the mammograms. This may have been because

our technicians were well-trained in the use of the

MammoPad prior to study commencement. No

mammograms required repetition.

With the use of MammoPad, Markle et al8

also reported a 4% decreased dose in the CC view,

but not the MLO view. In our study, there was

a 4.5% decrease in dose for the CC view and 6.5%

decrease in dose for the MLO view. These data were

statistically significant (P<0.05). With the use of the

MammoPad, the compression on breast tissue may

be more evenly distributed and account for the dose

reduction.

Although the improved comfort while using

the MammoPad and the dose reduction during

mammography are encouraging, our study has

several limitations. First, there might have been

patient selection bias. This study was performed

in a private hospital on Hong Kong Island. There

were no similar data available from public hospitals

elsewhere in Hong Kong so comparison was not

possible. In view of the small sample size, the results

might not be representative of the whole screening

population. As a result, there might have been an

inherent patient selection bias. This selection bias

might be minimised if a larger and representative

sample could be obtained. Second, since there is no

routine breast cancer screening programme in Hong

Kong, patients in this study were self-selected and

might be more motivated to undergo mammogram or

be more informed about such procedure. This might

in turn affect the pain and discomfort perception and

subsequent scores. In addition, the scoring system

for pain, coldness, and hardness was a 0-10 numeric

analogue scale system, which is a subjective scoring

system. Patient anxiety may result in a higher pain

score, and thus, a potential measurement bias might

exist. A thorough explanation before performing the

mammogram might help to reduce this bias.

The MammoPad was a single-use device with

obvious hygienic and safety advantages. In the United

States, the MammoPad can be recycled, although

this cannot be achieved in our unit at present. We

might explore the possibility of recycling the device

in future to decrease the environmental impact.

Conclusion

The use of MammoPad significantly reduced the

level of discomfort during mammography. This

should improve compliance with initial and follow-up

mammography. In addition, we demonstrated

radiation dose reduction in both CC and MLO

mammograms, which is another important benefit

of using MammoPad. We recommend the use of

MammoPad for screening mammography in all our

patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Betty ML Hung and Carmen

KM Lam for their assistance in preparation of the

questionnaires and data analysis.

References

1. Weedon-Fekjær H, Romundstad PR, Vatten LJ. Modern

mammography screening and breast cancer mortality:

population study. BMJ 2014;348:g3701. Crossref

2. Broeders M, Moss S, Nyström L, et al. The impact of

mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality in

Europe: a review of observational studies. J Med Screen

2012;19 Suppl 1:14-25. Crossref

3. Elwood M, McNoe B, Smith T, Bandaranayake M, Doyle

TC. Once is enough—why some women do not continue

to participate in a breast cancer screening programme. N Z

Med J 1998;111:180-3.

4. Shrestha S, Poulos A. The effect of verbal information

on the experience of discomfort in mammography.

Radiography 2001;7:271-7. Crossref

5. Lambertz CK, Johnson CJ, Montgomery PG, et al.

Premedication to reduce discomfort during screening

mammography. Radiology 2008;248:765-72. Crossref

6. Kornguth PJ, Rimer BK, Conaway MR, et al. Impact of

patient-controlled compression on the mammography

experience. Radiology 1993;186:99-102. Crossref

7. Tabar L, Lebovic GS, Hermann GD, Kaufman CS,

Alexander C, Sayre J. Clinical assessment of a radiolucent

cushion for mammography. Acta Radiol 2004;45:154-8. Crossref

8. Markle L, Roux S, Sayre JW. Reduction of discomfort

during mammography utilizing a radiolucent cushioning

pad. Breast J 2004;10:345-9. Crossref

9. Poulos A, Rickard M. Compression in mammography

and the perception of discomfort. Australas Radiol

1997;41:247-52. Crossref

10. Hong Kong Cancer Registry. Top ten cancers in 2013.

Available from: http://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/Statistics.html. Accessed Mar 2016.

11. Dibble SL, Israel J, Nussey B, Sayre JW, Brenner RJ, Sickles

EA. Mammography with breast cushions. Womens Health

Issues 2005;15:55-63. Crossref