Hong Kong Med J 2016 Apr;22(2):152–7 | Epub 26 Feb 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144476

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Importance of clothing removal in scalds

Edgar YK Lau, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery);

Yvonne YW Tam, MB, ChB, MRCS (HKICSC);

TW Chiu, BMBCh (Oxford), FRCS (Glasgow)

Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Edgar YK Lau (lyk685@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Objective: To test the hypothesis that prompt removal of clothing after scalds lessens the severity of injury.

Methods: This experimental study and case series

was carried out in the Burn Centre of a tertiary

hospital in Hong Kong. An experimental burn model

using Allevyn (Smith & Nephew Medical Limited,

Hull, England) as a skin substitute was designed to

test the effect of delayed clothing removal on skin

temperature using hot water and congee. Data of patients

admitted with scalding by congee over a 10-year

period (January 2005 to December 2014) were also

studied.

Results: A significant reduction in the temperature

of the skin model following a hot water scald was

detected only if clothing was removed within the

first 10 seconds of injury. With congee scalds,

the temperature of the skin model progressively

increased with further delay in clothing removal.

During the study period, 35 patients were admitted

with congee scalds to our unit via the emergency

department. The majority were children. Definite

conclusions supporting the importance of clothing

removal could not be drawn due to our small sample

size. Nonetheless, our data suggest that appropriate

prehospital burn management can reduce patient

morbidity.

Conclusions: Prompt removal of clothing after

scalding by congee may reduce post-burn morbidity.

New knowledge added by this study

- In hot water scalds, immediate clothing removal may lead to less severe injury.

- In congee scalds, severity of injury can potentially be reduced with earlier removal of clothing.

- Adequate post-injury first aid with water in congee scalds may lower the chance of requiring surgical intervention.

- Parents should be educated about scald prevention as it is prevalent in the paediatric population.

- It should be emphasised to the general public that immediate clothing removal, along with first aid by running cool water over the burn for 20 minutes within the first 3 hours of injury, could potentially reduce the severity of scald.

- Frontline medical staff should be aware of the importance of prehospital burn management so that relevant questions can be raised during the initial hospital admission.

Introduction

In Hong Kong, as in most developed countries, one of the

most common types of burn injury that requires

hospital admission is scald. If we view a scald as a

‘contact burns due to a liquid’, the severity of burn

injury will be a function of starting temperature,

contact time, and the thermal capacity of the

causative agent. In a previous study performed in

our centre, it was hypothesised that both viscosity

and thermal capacity of the agent were important

factors in prolonging heat exposure of the skin.1

Patients who were scalded by congee (a popular local

dish where rice with excess water is simmered until a

porridge-like mixture is formed) were more likely to

require surgery than those scalded by hot water (31%

vs 14%, respectively).1 This may be partly explained

by congee’s greater thermal capacity (causing more

effective heat transfer) and viscosity (prolonging

contact time).

In order to minimise the severity of burn

injury, it is essential that effective first-aid measures

be properly taught to the public. The two basic

principles are to stop the burning process and to

cool the burn wound. As patients are usually wearing

clothes and underwear at the time of scalding, the

most effective way to achieve the first objective is to

remove the involved clothing as quickly as possible.

For many reasons, however, this straightforward act

is sometimes not performed in a timely manner (eg

scald occurring in a restaurant where a patron is

too embarrassed to take off his/her clothing or simple

ignorance of first aid). It is in this context that a simple

model was designed in an attempt to demonstrate

the importance of prompt clothing removal after

scalding has occurred.

Methods

In the first part of our study, the effect of delayed

clothing removal on skin temperature was assessed

using our experimental burn model. As in our

centre’s previous study, a piece of Allevyn foam

dressing (Smith & Nephew Medical Limited, Hull,

England) served as our skin model. It was placed on

a metal plate above a heated water bath (JP Selecta,

Barcelona, Spain) until its surface temperature

reached 34°C when measured using the Raytek non-contact

thermometer (Raytek Corporation, Santa

Cruz [CA], US) 1 cm above the centre, in an attempt

to simulate ‘skin temperature’. Cotton underwear

was then placed on top of the Allevyn dressing. The

scalding agents (hot water and congee) were boiled

to 88°C and poured onto the model. The underwear

was then removed at various times following the

‘injury’ (10, 20, 30, 60, and 120 seconds). The

temperature of the Allevyn was immediately

measured at the aforementioned position by the

same observer starting from the moment of clothing

removal and every 10 seconds thereafter for 2

minutes. The same procedure was repeated 3

times for each time interval, and the mean value was

taken as the final data point. Standard cooling curves

were subsequently plotted using these average data

points along with calculated standard deviations.

In the second part, all patients admitted to our

unit via the emergency department with scalding

by congee over a 10-year period (January 2005 to

December 2014) were first retrospectively identified

from our hospital’s computer records. Clinical notes

were physically traced in order to examine the

admission details as well as subsequent management

of the patients.

Results

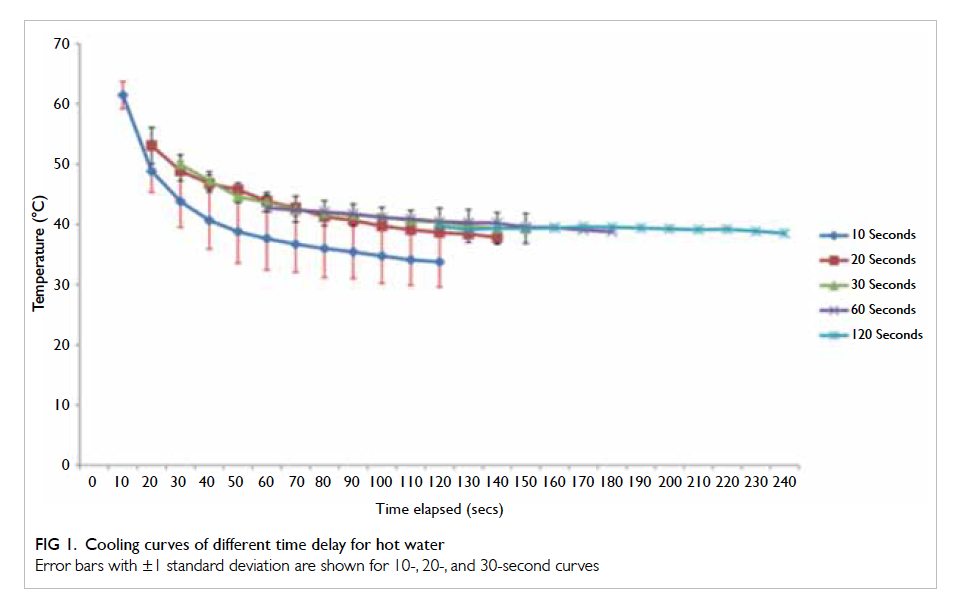

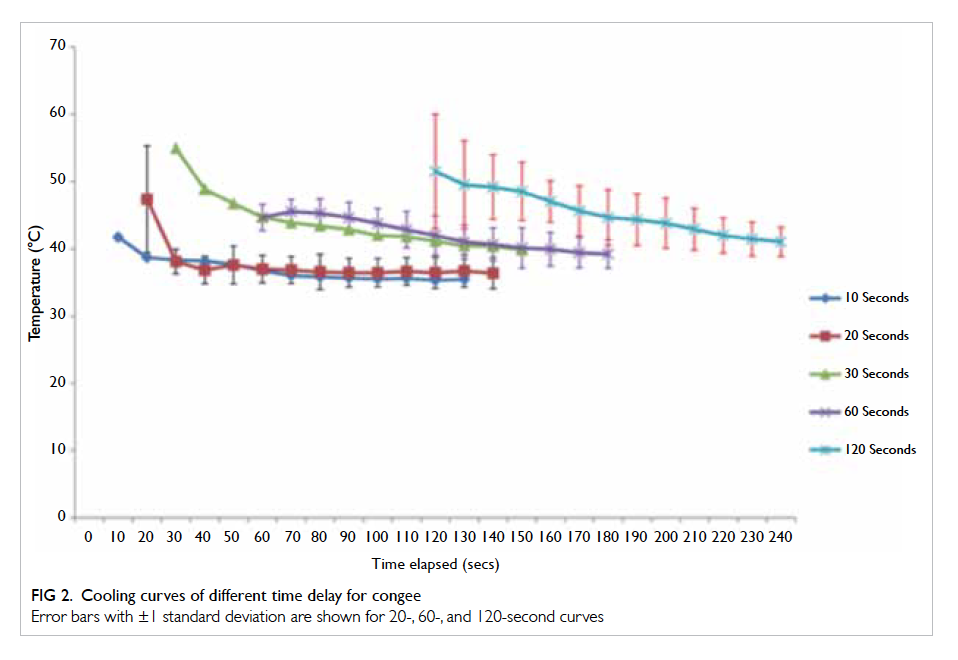

The results of our experimental burn model are shown

in Figures 1 and 2. The temperature of the Allevyn

partly reflected the amount of heat transferred from

the causative agent. A higher cooling curve translated

to a higher skin temperature (hence higher potential

injury). Examination of the cooling curves revealed a

difference in the behaviour of hot water and congee.

With hot water, the 10-second cooling curve was

lower than its counterparts (the 20-, 30-, 60-, and

120-second cooling curves) that essentially lie along

the same curve above. With congee, the cooling

curves appeared to lie progressively higher with

further delay in clothing removal—the 30- and 60-second cooling curves were in a significantly higher

position compared with the 10- and 20-second

cooling curves, while the 120-second cooling curve

was higher than that of 30 and 60 seconds.

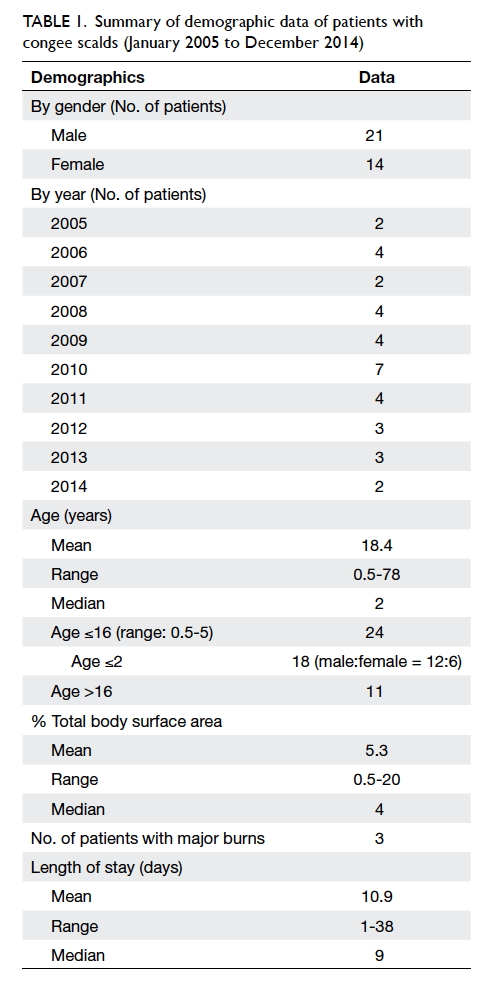

During the study period, 35 patients were

admitted (21 males, 14 females) for scalding by

congee. Of note, two paediatric patients were

admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for initial

resuscitation due to the extent of their burns (16%

and 20% of total body surface area [TBSA]) and

one patient was discharged against medical advice

after being admitted for 1 day. The demographic

distribution, percentage of TBSA burnt, and length

of hospital stay are shown in Table 1. On average, our

unit admitted two to four cases per year except in 2010

when there were seven cases. Although most of these

congee scalds were relatively minor as evidenced

by the small mean percentage of TBSA involved and

a mean hospital stay of approximately 11 days,

more than two thirds of patients were children.

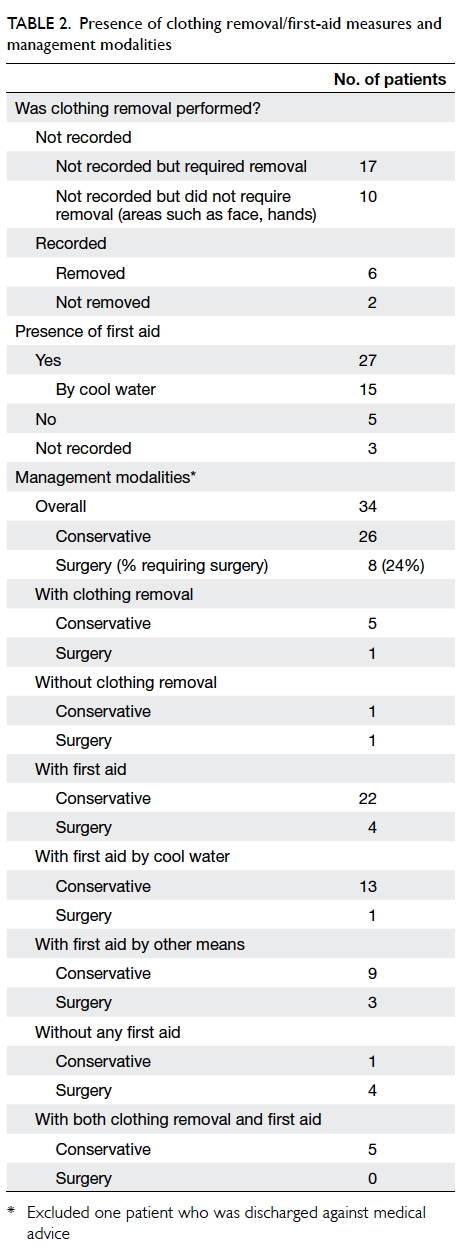

Table 2 shows the statistics for clothing removal/first-aid measures and the subsequent management.

While most of our patients received some form of first aid, it was found that the act of clothing removal was not documented in the majority (27/35) of cases. Despite an extended review period, it is recognised that

the sample size remains small. Consequently, only

descriptive statistics could be shown and a formal

statistical analysis could not be conducted for this

retrospective review. Nonetheless, those patients

who received first aid or in whom clothing was

removed (or both) did seem to fare better than those

without.

Discussion

This was a preliminary study of the potential

relationship between the time of clothing removal

and depth of scald burns. While ‘cooling the burn

wound’ is an important step in the first-aid process,

it must be recognised that ‘stop the burning process’

should take precedence in order to maximise the

benefit of first aid. To this end, the contact time of the

offending agent with the skin should be minimised.

A cooling study was performed by our centre in

2006 to examine the cooling curves of different

food/drinks. Of seven common agents examined

for their rate of cooling, congee cooled significantly

slower compared with the other agents (eg tea,

coffee, noodles, etc).1 It was also shown that a higher

percentage of patients required surgery if scalded

by congee compared with hot water. As congee is a

common dish for children in Hong Kong from which

scalds could lead to greater morbidity, congee was

specifically selected for further investigation.

We showed that delay in clothing removal

could increase the severity of scald burns by congee

as demonstrated by the increased temperature in

our skin model when clothing removal was delayed.

The experiment did not persist beyond a delay of 120

seconds since clothing would generally be removed

within that time or not at all.

Hot water was first examined as a ‘control’

compared with congee. In our results, the cooling

curves of 20, 30, 60, and 120 seconds essentially

lay along the same curvature while the 10-second

cooling curve was significantly lower. This implies

that if clothing removal occurs within the first 10

seconds, the surface temperature of our skin model

would be significantly lower at all subsequent time

points; thus in hot water scalds, immediate clothing

removal may prove to be the most beneficial.

On subsequent examination of the effect of

congee, the cooling curves behaved differently—there appeared to be a stepwise progression from the

10- and 20-second curves to the 30- and 60-second

curves, and then finally to the 120-second curve.

Observation of the error bars showed that the 10- and 20-second curves did not differ significantly and

this also applied to the 30- and 60-second curves.

The 120-second curve generally lay significantly

above the rest; therefore, it appears that delay in

clothing removal significantly affected the surface

temperature of our skin model—removing it within

the first 20 seconds may lead to a less-severe injury

compared with a 30- to 60-second delay, which in

turn is better than a 2-minute delay.

At the time points between 120 and 140 seconds

where all the curves have overlapping temperature

measurements, one is able to observe that there are

three distinct ‘tiers’ (10/20, 30/60, 120 seconds). In

our model, heat was transferred to the Allevyn with

the garment initially acting as a ‘barrier’ since the

underwear was removed before the congee could

soak through, resulting in a lower temperature

detected. By increasing the time interval, the garment

increasingly acted as a ‘reservoir’ for heat as the

congee gradually soaked through. Due to the greater

thermal capacity and viscosity of congee compared

with water, the temperature of the entire ‘congee-underwear-Allevyn complex’ was maintained with

more heat being transferred to the Allevyn for the

same given period, resulting in a higher temperature

detected. Overall, our findings corroborate our

hypothesis that with a viscous agent such as congee,

the severity of scald burns could potentially be

reduced with earlier removal of clothing as evidenced

by lower temperatures detected in our skin model.

Although our experimental study did succeed

in demonstrating effects in our skin model, the ideal

model for this study would be human skin (eg cadaveric

or surgically excised) but it is rather difficult to

source in practice. For the sake of scientific reproducibility,

Allevyn was used instead (a bilayer dressing

material with an outer waterproof layer analogous to

the epidermis along with an inner absorbent sponge

layer). Although Allevyn does not exactly mimic the

‘in-vivo’ behaviour of human skin per se, this model allows the opportunity for comparative

study. Another potential improvement of our model

is to set up a thermometer to measure the skin

model’s temperature underneath the surface so that

temperature can be tracked while clothing is still in

place. In this experimental model, we were only able

to measure the temperature after the garment was

removed. Having continual temperature monitoring

would enable us to plot ‘complete’ curves starting

from 0 second onwards for all five time intervals,

and the temperature change both before and after

clothing removal could be more accurately depicted.

In an early study by Moritz and Henriques,2 porcine

skin was found to bear a remarkable resemblance

to human skin. If the experiment can be repeated

with porcine skin along with improved accuracy

of temperature measurement (ie setting up a

thermometer intradermally within the porcine skin),

the validity of our conclusions may be strengthened.

Nonetheless, this experimental study lends support

to the notion that timely clothing removal before

first-aid application may reduce the severity of burn

injury.

The paediatric population (especially those

under the age of 2 years) is particularly susceptible to

scalds with a male preponderance.3 4 5 This age-group is

particularly vulnerable as it is an age of great curiosity

about the environment (hence the tendency to grab/tip over things) but limited motor development does

not allow a child to move away from danger, such as

a falling bowl of congee. It is also compounded by the

fact that children have relatively thinner skin and this

results in more significant injuries. Our statistics from

this congee scald review do not deviate much from

our centre’s previous experience: slightly over 50% of

our patients were aged 2 years or younger with a male

predominance, and 24 out of 35 patients were within

the paediatric age-group.

It seems almost intuitive that clothing should

be removed as soon as possible whenever a scald

burn is sustained. This may not necessarily be so. In

a recent UK study where parents were interviewed

and asked about first-aid measures they would

provide for a child with a large scald, 61% of parents

failed to state that clothes should be stripped

and several thought that it would cause further

skin damage.6 The question of whether removing clothing would cause further skin damage is commonly asked by parents of paediatric

burn patients admitted to our unit.

In our retrospective review, analysis of the

efficacy of clothing removal was hindered because

such action was not recorded in the majority of cases

(27 out of 35). The location of burns was further

studied: in 10 of these 27 cases, injury occurred over

an exposed area (eg face and hands), while the

remaining 17 cases could have benefited from clothing

removal. In six of eight patients where clothing was

removed, the exact timing was not documented.

Such lack of documentation demonstrates the benefit

of education about prehospital treatment for both

the public and frontline medical staff. An increased

awareness of correct prehospital treatment of burns

would mean relevant questions are asked during

history taking, and this would facilitate proper documentation

and subsequent patient management. As mentioned

in the Results section, our sample size did not

permit any meaningful statistical analysis to be

carried out pertaining to the potential usefulness of

early clothing removal in reducing morbidity from

scalds. Nonetheless, it appeared that those patients

who had clothing removed fared quite well. One

exception was a 50-year-old man with a relatively

larger scald (TBSA, 13%) involving the face/neck/chest/bilateral upper limbs who eventually required

skin grafting.

After the burning process is stopped, the next

logical step is to cool the burn by applying first

aid. Ideally, first aid for burns should provide pain

relief and reduce potential morbidity associated

with the injury. Although many first-aid treatments

to cool burns have been studied, the application of

cold water has the strongest supporting evidence.

Currently, an ‘adequate’ first aid is defined as 20

minutes of running tap water over the burn within

the first 3 hours of injury.7 Apart from removing

heat energy from the damaged tissue, the benefits

of cooling continue and include decreased oedema

formation, preservation of dermal perfusion,

decreased inflammatory response, and improved

wound healing.8 9 Regrettably, our centre’s previously published paper showed that first aid was applied

only to half of our paediatric patients.5 In our current

review, although 27 patients received some form of

first aid, only 15 (43%) patients received cool-water

treatment of variable duration. The duration of first

aid with cool water was either not recorded or fell

short of the recommended 20 minutes. This state of

affairs is certainly unsatisfactory and more public

education is warranted.

Our data once again do not enable formal

statistical analysis, and a number of factors such

as percentage of TBSA burnt and depth of burn would affect

the eventual outcome of our patients. Nonetheless,

it does appear that those who received first aid

required fewer surgeries. Detailed analysis of those

who received no first aid revealed that none of the

burns was classified as major even though four out

of eight patients underwent skin grafting. In patients

who received cool water as first aid, only one needed

surgery—a 14-month-old boy with a TBSA of 13.5%

burnt involving the left flank and bilateral lower

limbs. In patients who received other types of first

aid, three required surgeries (one of whom had a

major burn and required ICU admission). Of note, for

patients in whom clothing was removed and first-aid

measures applied, all were managed conservatively.

Although definite conclusions from our data cannot

be drawn, clothing removal and first aid do seem to

have beneficial effects, especially in smaller burns

that constitute most of our case load. It is our

hope that with better medical documentation and

education of our frontline staff, the quality of our

future data can be enhanced with a view to facilitate

formal data analysis.

Before a simple and effective message can be

delivered to the public about post-burn prehospital

management, it is equally important to consider

the local food characteristics. For instance, the

population of Hong Kong may find it easier to relate

burns to congee or cup noodle than burns to coffee.

Since half of our paediatric burn patients received

no first aid upon admission, simply emphasising

the importance of ‘stop the burning process’ may

reduce potential morbidity. Our experimental skin

model showed that earlier clothing removal post-burn

reduces skin temperature and thus beneficial.

Although our retrospective review was unable

to reflect any concrete statistical results, it was

certainly suggestive of the potential usefulness of

proper prehospital management. Last but not least,

the financial cost of managing acute uncomplicated

minor paediatric scalds is significant (including

hospital beds, theatre visits, dressings, medications

etc). This is an important social and economic issue

since burns sustained by children often require

many years of follow-up for scar management and

psychosocial support.10 If preventive measures fail

and accidents occur, it is in the best interests of the

public to understand how to minimise morbidity.

References

1. Chiu TW, Ng DC, Burd A. Properties of matter matter in

assessment of scald injuries. Burns 2007;33:185-8. Crossref

2. Moritz AR, Henriques FC. Studies of thermal injury: II. The

relative importance of time and surface temperature in the

causation of cutaneous burns. Am J Pathol 1947;23:695-720.

3. Ray JG. Burns in young children: a study of the mechanism

of burns in children aged 5 years and under in the Hamilton,

Ontario Burn Unit. Burns 1995;21:463-6. Crossref

4. Dewar DJ, Magson CL, Fraser JF, Crighton L, Kimble RM.

Hot beverage scalds in Australian children. J Burn Care

Rehabil 2004;25:224-7. Crossref

5. Tse T, Poon CH, Tse KH, Tsui TK, Ayyappan T, Burd A.

Paediatric burn prevention: an epidemiological approach.

Burns 2006;32:229-34. Crossref

6. Graham HE, Bache SE, Muthayya P, Baker J, Ralston DR.

Are parents in the UK equipped to provide adequate burns

first aid? Burns 2012;38:438-43. Crossref

7. First aid. Australian and New Zealand Burn Association.

Available from: http://anzba.org.au/care/first-aid/.

Accessed Feb 2016.

8. Cuttle L, Pearn J, McMillan JR, Kimble RM. A review of

first aid treatments for burn injuries. Burns 2009;35:768-75. Crossref

9. Wright EH, Harris AL, Furniss D. Cooling of burns:

mechanisms and models. Burns 2015;41:882-9. Crossref

10. Griffiths HR, Thornton KL, Clements CM, Burge TS,

Kay AR, Young AE. The cost of a hot drink scald. Burns

2006;32:372-4. Crossref