Hong Kong Med J 2016 Apr;22(2):184.e3–4

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154821

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Median arcuate ligament syndrome

FH Ng, MB, ChB, FRCR;

Ophelia KH Wai, MB, ChB, FRCR;

Agnes WY Wong, MB, ChB, FRCR;

SM Yu, MB, ChB, FRCR

Department of Radiology and Organ Imaging, United Christian Hospital,

Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr FH Ng (nfh667@ha.org.hk)

Case

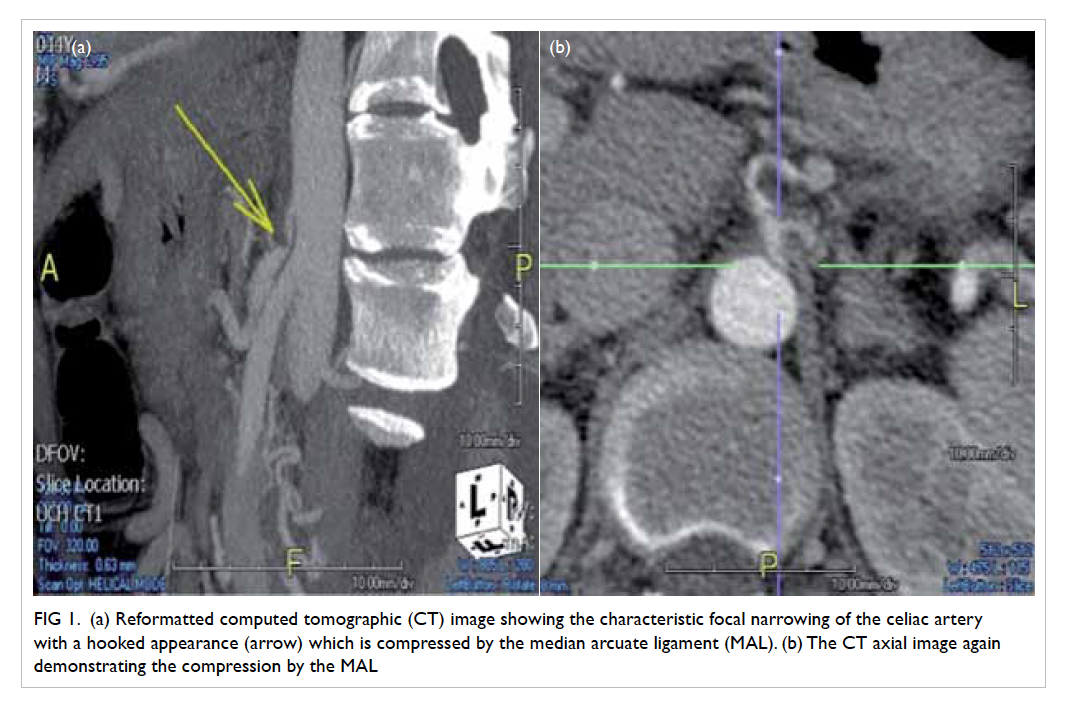

A middle-aged man admitted with abdominal

pain and anaemia in December 2015. A computed

tomographic (CT) angiogram demonstrated a

superior indentation with focal narrowing in the

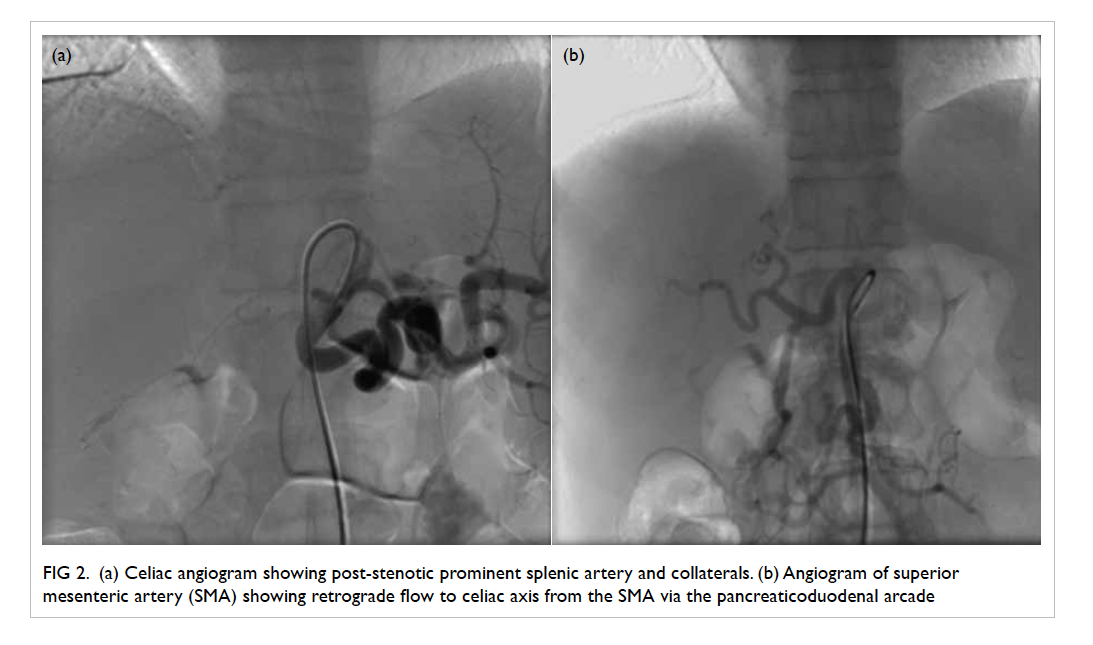

proximal celiac axis (Fig 1). Conventional superior

mesenteric arteriogram demonstrated prominent

collaterals, and retrograde flow of contrast from the

superior mesenteric artery (SMA) to the hepatic

arteries (Fig 2). It was likely related to chronic

compression of the proximal celiac artery. Low

insertion of the median arcuate ligament (MAL) can

be found in normal asymptomatic people. In this

case, prominent collaterals and the retrograde flow

from the SMA supported the diagnosis and may

have explained his symptoms. In symptomatic cases,

surgical division of the median arcuate ligament is

the mainstay of treatment.

Figure 1. (a) Reformatted computed tomographic (CT) image showing the characteristic focal narrowing of the celiac artery with a hooked appearance (arrow) which is compressed by the median arcuate ligament (MAL). (b) The CT axial image again demonstrating the compression by the MAL

Figure 2. (a) Celiac angiogram showing post-stenotic prominent splenic artery and collaterals. (b) Angiogram of superior mesenteric artery (SMA) showing retrograde flow to celiac axis from the SMA via the pancreaticoduodenal arcade

Discussion

The MAL is a fibrous arch that unites the

diaphragmatic crura on either side of the aortic

hiatus. The crura pass superior and anterior to

surround the aortic opening and to join the central

tendon of the diaphragm. The ligament usually passes

superior to the origin of the celiac axis. The insertion

of the ligament may be low and therefore crossover

the proximal portion of the celiac axis, causing

a characteristic indentation. If it is significantly

compressed on the celiac axis, this will compromise

vascular flow and produce symptoms.

The MAL syndrome was first described in

1963 by Harjola1 and in 1965 by Dunbar et al.2 The definition of the syndrome relies on a combination

of both clinical and radiographic features. Clinically,

they described a classical triad of chronic postprandial

abdominal pain, epigastric bruit, and weight loss.3 4 Extrinsic compression of the celiac trunk by the

MAL occurs in 10% to 24% of patients.1 Usually,

patients are asymptomatic and the classical triad

is not always present, presumably due to collateral

supply from the superior mesenteric circulation.1 2 The disease typically occurs in young patients and

is more common in thin women who may present

with epigastric pain and weight loss.1 The abdominal

pain may be associated with eating, but not always.1

On physical examination, an abdominal bruit that

varies with respiration may be audible in the mid-epigastric

region. Symptoms are thought to arise

from compression of the celiac axis with consequent

compromised blood flow.

The diagnosis of celiac artery compression

is traditionally made following conventional

angiography. The use of thin-section multidetector

CT and three-dimensional imaging techniques

has greatly improved the ability to non-invasively

obtain detailed images of the mesenteric vessels.

Compression of the celiac axis by the MAL

produces characteristic findings visible on CT

angiography. Computed tomographic angiography

can play a role in the diagnosis of this condition by

demonstrating the characteristic focal narrowing of

the celiac artery (Fig 1) with a hooked appearance

that distinguishes this condition from other causes

of celiac artery narrowing, such as atherosclerotic

disease. Indentation of the origin of coeliac artery is

exacerbated during the expiratory phase. Repeating

CT on inspiration can often distinguish clinically

significant narrowing from transient compression

seen only during expiration in some patients, and is

how most abdominal CT studies are performed.1

The majority of affected patients have no

symptoms, thus radiographic finding of celiac

axis compression alone may not be significant,

unless it is correlated with clinical symptoms.

Severe compression occurs in approximately 1% of

patients.1 Severe stenosis will result in post-stenotic

dilatation, and in some cases, the celiac axis will be

fed by the SMA via the pancreaticoduodenal arcade.

This was evident on the angiogram of our patient

with prominent collaterals and retrograde flow

from the SMA (Fig 2). His CT angiogram showed a

characteristic hooked focal narrowing at the superior

proximal celiac artery (Fig 1).

The surgical management of MAL syndrome

is controversial.1 2 Surgical treatment in severe cases is advocated, particularly in cases with post-stenotic

dilatation and collateral vessels (Fig 2), by division

of the ligament. A laparoscopic approach is being

increasingly adopted. Celiac angioplasty and stenting

by endovascular means may be a future hot topic.2

References

1. Harjola PT. A rare obstruction of the coeliac artery: report

of a case. Ann Chir Gynaecol Fenn 1963;52:547-50.

2. Dunbar JD, Molnar W, Beman FF, Marable SA.

Compression of the celiac artery and abdominal angina.

Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1965;95:731-44. Crossref

3. Horton KM, Talamini MA, Fishman EK. Median arcuate

ligament syndrome: evaluation with CT angiography.

Radiographics 2005;25:1177-82. Crossref

4. Duffy AJ, Panait L, Eisenberg D, Bell RL, Roberts KE,

Sumpio B. Management of median arcuate ligament

syndrome: a new paradigm. Ann Vasc Surg 2009;23:778-84. Crossref